Chapter 2: Montana & Wyoming in Depth

Spectacular scenery combines with a genuine frontier history to create what I consider the real American West. The land is mostly uncluttered—even the so-called cities are little more than overgrown cow towns—and the setting is one of rugged beauty, from southeast Yellowstone’s Thorofare country (said to be the most remote wilderness in the lower 48 states), to the river valleys where Sacajawea led Lewis and Clark, to the sandstone arroyos of famed outlaw Butch Cassidy’s Hole-in-the-Wall country.

There’s a little more pavement here than there was in years gone by, but the open horizon and hospitality—along with a pronounced independent spirit among the locals—still exist in Montana and Wyoming. Your first visit will likely be centered on the scenery, the outdoor recreation, and the region’s Wild West history, but these two states have even more to offer.

Montana & Wyoming Today

Since the 1950s, the story of Montana has been an evolving one, with tourism and agriculture playing key economic roles. Primary crops include wheat, cherries, sunflowers, and sugar beets, as well as beef. Growth has emerged as a key, often divisive issue, as areas like Whitefish and Bozeman have attracted wealthy newcomers from out of state and the population has steadily ticked toward 1 million. But large chunks of Montana are far outside the fast track and have remained relatively unchanged for several generations. Likewise, Wyoming depends on agriculture and tourism, but leaned more heavily on oil and gas than its neighbor to the north.

Both states are known for their conservative politics, although Montana has a long and storied history of progressive, labor-oriented politics as well. This makes Montana much more of a swing state when it comes to national elections; many Democrats win elections here.

Unfortunately, mining, logging, and housing developments have impacted the area known as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that surrounds Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. The ecosystem is an interdependent system of watersheds, mountain ranges, wildlife habitat, and other components extending beyond the two parks into seven national forests, an Indian reservation, three national wildlife refuges, and nearly a million acres of private land. To put it into perspective, the ecosystem’s 18 million acres span an area as big as Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Delaware combined. It is one of the largest intact temperate ecosystems on the planet.

Park officials have the dual—and often contradictory—missions of conserving the natural environment and providing recreational access to three million visitors a year, each with a different definition for the word wilderness. The roads and facilities necessary to open the parks to the public are often at odds with the concept of conservation, and the human impact on the environment is no small thing. Recent years have seen record levels of visitors to both parks in spite of difficult economic times, which makes for even more potential conflict between man and wild. In 2011, two visitors to Yellowstone were fatally mauled by grizzly bears—something that had not happened in the park in over 25 years, and a haunting reminder of the inherent dangers that come along balancing conservation and tourism.

Gray wolves, which were eliminated in the 1920s and reintroduced in the 1990s, have been a crucible for conflict. Many ranchers whose lands border the parks have fought the reintroduction tooth and nail, despite the fact that they are compensated when they lose livestock to a wolf. Gray wolves now number about 1,500 in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming; single animals have turned up in Utah and Colorado, but permanent populations have yet to be established. In 2011, the U.S. Congress passed a spending bill that had a rider attached to it allowing legal wolf hunts to take place in both Montana and Wyoming—despite the endangered status of these wolves. The controversy does not look like it will be going away anytime soon.

Snowmobiles in Yellowstone have also generated their fair share of controversy in the past decade or so. While the machines were to be banned under a plan put in place by the Clinton administration, the Bush administration implemented an alternative compromise of a quota system and best-available technology. The gateway towns of West Yellowstone, Jackson, and Gardiner remain popular jumping-off points for park tours, park officials are still studying the long-term environmental impact of the machines, and snowmobiles still share narrow trails with wildlife during months when the animals’ energy levels are at their lowest.

Though the ranching community has dominated Wyoming politics for most of the past century, the modern economic hammer in the state is undoubtedly the energy industry. The state’s fate has been closely tied to oil, gas, and coal, with the economy rising and falling in synch with world prices. But in recent years, the state has tallied billion-dollar surpluses, thanks to the extraction industries. The boom and bust of the energy industry has prompted repeated calls for a more diversified economy, and in recent years, Wyoming’s tourism industry has begun to have an impact. This proved critical when drilling slowed when commodity prices plunged in 2008, but the oil and gas industry has bounced back strong as prices have risen in the time since. Nonetheless, Wyoming remains a predominantly rural state—and by far the least populous in the union, with about 570,000 residents as of 2011.

Montana Dateline

11,000 b.c. Earliest evidence of humans in Montana.

a.d. 1620s Arrival of the Plains Indians.

1803 The eastern part of Montana becomes a territory through the Louisiana Purchase.

1805–06 Explorers Lewis and Clark journey through the Northern Rockies to and from the Pacific coast.

1864 Montana becomes an official territory. Gold is discovered at Last Chance Gulch in Helena.

1876 Defeat of George A. Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

1877 Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce tribe surrenders to U.S. soldiers in the Bear Paw Mountains.

1880 The Utah and Northern Railroad enters Montana.

1883 The Northern Pacific Railroad crosses Montana.

1889 Montana, on November 8, becomes the 41st state in the Union.

1893 The University of Montana in Missoula and Montana State University in Bozeman are founded.

1910 Glacier National Park is established.

1917–19 Missoula native Jeannette Rankin, a Republican, becomes the first woman elected to U.S. Congress and votes against U.S. participation in World War I.

1940 Fort Peck Dam is completed.

1965 Construction of Yellowtail Dam is completed.

1973 Montana’s third state constitution goes into effect.

1983 Anaconda Copper Mining Company shuts down.

1986 Montana spends $56 million on environmental protection programs.

1995 Wolves are reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park. Daytime speed limits are abolished (but later reestablished).

1996 Recluse Theodore Kaczynski, dubbed the Unabomber, is arrested at his cabin near Lincoln and is later sentenced to life in prison for sending a series of mail bombs that killed three people.

1998 The $6-million Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center opens in Great Falls.

2000–01 A series of forest fires—mostly wildfires, but some caused by careless humans—drive thousands of people from their homes and do millions of dollars in damage.

2003 Wildfires burn 140,000 acres in Glacier National Park.

2005 The grizzly bear is removed from the endangered species list.

2006 A powerful November rainstorm washes out a chunk of Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park.

2007–08 Over 1,500 Yellowstone bison are killed as they cross into Montana due to brucellosis fears.

2008 The gray wolf population in the Northern Rockies hits 1,600; the species is no longer listed as endangered.

2009 Montana has its first legal wolf hunting season since reintroduction in 1995.

2010 Separate court rulings return the grizzly bear and gray wolf to the endangered species list.

Looking Back: Montana & Wyoming History

Montana

In the Beginning

The first people believed to have wondered at the land we now call Montana were Folsom Man, who arrived sometime after the end of the last Ice Age about 12,000 years ago and lived here until superseded by the Yuma culture about 6,800 years ago.

Then about 3,000 years ago, a more modern American-Indian culture began to emerge, eventually evolving into the Kootenai, Kalispell, Flathead, Shoshone, Crow, Blackfeet, Chippewa, Cree, Cheyenne, Gros Ventres, and Assiniboine.

European Explorers (18th C.)

The first European known to enter Montana was Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye.

Vérendrye had heard of a river that flowed to the western sea and was looking for the Northwest Passage. He came in 1738 but retreated. Two of his sons, Pierre and François, returned in 1743 and described the “shining mountains,” generally believed to be the Bighorns of southern Montana and northern Wyoming. But threats of a looming Indian war discouraged the brothers, and they returned to Montreal. No other white men are known to have come here for another 60 years.

When they finally did arrive, they were with the expedition of Lewis and Clark. The explorers reached the mouth of the Yellowstone River on April 26, 1805, and pushed upriver to the Shoshone, where they were warmly greeted, the result of having coincidentally brought Shoshone chief Cameahwait’s long-lost sister, Sacajawea, with them as one of their guides.

Settlement (19th C.)

The first industry in Montana, at least for non-Indians, was trapping. John Jacob Astor, Alexander Ross, and William Ashley brought in their hearty voyageurs to clear the country of beaver for the European hat market.

The discovery of gold opened Montana’s Wild West era. The lure of easy money, plus the fact that these towns were some 400 miles from official justice, attracted outlaws, con artists, and ladies of the night from all over the West.

In 1864, just as gold was discovered in Last Chance Gulch in present-day Helena, the Montana Territory was formed and Sidney Edgerton became the first territorial governor. The capital was moved to Virginia City, and a constitutional convention was called as the first step toward statehood. A constitution was drafted and sent to St. Louis for printing but was lost somewhere along the way.

In 1884, another constitution was drafted. This one didn’t work either, for one reason or another, and in 1889, the now well-practiced delegates came up with a third one. Taking no chances, they prefaced it with the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution. Montana finally became a state in November 1889.

Trouble Between the Indians & the Settlers

Montana’s Indian tribes were not at first invariably hostile to the whites, and signed a number of treaties signaling their peaceful intentions. But the influx of settlers and the confinement of tribes to reservations resulted in dissatisfaction among the original inhabitants and escalating hostilities against the whites. In 1876, the War Department launched a campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne. At the end of June that year, this culminated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the death of all of the command under Gen. George Armstrong Custer.

The Indian victory was only a temporary setback for the whites, however, and by 1880, all the Indians had been forced onto reservations. The last action of the Indian War period occurred in Montana with the heroic flight of Chief Joseph’s Nez Perce from their northern Idaho reservation toward Canada in 1877.

Industrialization (Late 19th c.)

When copper was first discovered in the silver mines in Butte, no one could have foretold its effects on Montana’s future. When copper wiring became an integral part of several new electrical technologies, Butte copper became an important resource for America. One of the first men to profit was Marcus Daly, an Irish immigrant who arrived in Butte in his mid-30s and purchased his first mine, which yielded incredibly large amounts of the purest copper in the world.

William A. Clark, another copper-mine baron, was a Horatio Alger type. An average youth from Pennsylvania, he rooted around in mines until his efforts took him to Montana. He had a keen business acumen that prompted him to purchase mining operations, electric companies, water companies, and banks. He quickly amassed a great deal of wealth; then his inflated ego drove him to the political arena. His was the major voice in the territorial constitution proceedings in 1884, and when Montana held its last territorial election, Clark was determined to get into public office as Montana’s representative.

A war commenced between Daly and Clark, rooted in Clark’s determination to hold political office and Daly’s unwillingness to see him do it. Montana finally became a state in 1889, after 5 tough years of appeals to the U.S. Congress. The bellicose millionaires were so set on controlling the young state’s political interests that they purchased or created newspapers to give themselves a printed voice. They stuffed money into the pockets of voters and agreed on nothing. In Montana’s first congressional election, Clark fell three votes shy of his bid, and the legislature adjourned without selecting a second senator, leaving Montana with only half of its due representation in Washington.

The fight for capital status came along in 1894. Helena had been the capital, but the constitution held that the site must be determined by the voters. Daly wanted his newly created Anaconda to be the capital; Clark was happy with the status quo. The fact that Anaconda was ruled by the strong arm of the Anaconda Mining Company caused voters to turn to the diversified ways of Helena. For once in his life, William Clark was not only rich, but also appreciated by the masses. Or so it seemed.

With his thirst for public office revitalized, Clark did his best to buy his way into the U.S. Senate and actually pulled it off. Daly, infuriated by the way his bitter enemy had achieved his seat, demanded an investigation by the Senate. The investigation uncovered a wealth of improprieties on Clark’s part, so he resigned. Down but not out, Clark took a deep breath and plunged immediately back into the thick of things. Once when Robert Burns Smith, governor of Montana and hardly an ardent admirer of Clark’s, was out of town, Clark arranged for his friend A. E. Spriggs, the lieutenant governor, to appoint Clark to the U.S. Senate. This lunatic act embarrassed the state of Montana, causing Smith to nullify the appointment upon his return. Meanwhile, Daly had sold his Anaconda Copper Company to Standard Oil to form the Amalgamated Copper Company, and Clark was now up against a nameless, faceless opponent.

He chose to link his fate with another, younger copper king, Augustus Heinze, hoping to form an alliance that Amalgamated couldn’t match. At this time, Heinze was more influential than the older, less active Clark, and the team of Heinze and Clark soon had complete control of the mining world in Montana. It seemed as if Clark’s last wish—to garner the Senate post he had been denied for so long—would be realized with Heinze’s help. And so it was—Clark served his state as a senator from 1901 to 1907.

The 20th Century

At the beginning of the 20th century, Montana experienced a boom of a different type. The Indian Wars had ended, and white settlers declared the land a safe and fertile haven for farming. The U.S. government helped things along in 1909 when it passed the Enlarged Homestead Act, giving 320 acres to anyone willing to stay on it for at least 5 months out of the year for a minimum of 3 years. Homesteaders arrived from all over the country to stake a piece of land.

Sentiment for the homesteaders was never good, and the generalization that homesteaders were stupid, dirty people became increasingly popular. The truth is that Montana’s agricultural backbone was created by these extraordinary people who came west to establish farms. Wheat became—and still is—the major crop in such areas as the Judith Basin, in the center of the state, and Choteau County, north of Great Falls. The mining of copper and other minerals was also strong throughout much of the 1900s, centered on Butte, as was logging in northwestern Montana.

When the Great Depression hit Montana, farming was challenged by severe drought, and jobs were nowhere to be found. Roosevelt’s New Deal was a lifesaver. Without the jobs created by the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration, the state might have never recovered its economic balance. Of particular help was construction of the Fort Peck Dam in the mid-1930s, which employed more than 50,000 workers. The earth-filled dam, the largest of its kind in the world, took almost 5 years to complete.

Modern Montana

After going strong for a century, Montana’s copper age came to an end in the early 1980s, when mining ceased at mines in and around Butte. However, the legacy of mineral extraction remains, in the form of environmental degradation and toxic Superfund sites in need of remediation. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has cleaned up (or is cleaning up) many such sites, including ones near Butte and Missoula, but they remain a threat to the groundwater in some areas.

As tourism has grown, largely driven by the national parks, so have the real-estate and service industries. However, the state’s ranching legacy or extractive industries certainly have not gone away. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, logging and mining have remained relatively strong here, but many other industries (including construction, government, and healthcare) employ more people today.

Politically, Montana is known for a progressive history and a libertarian streak, having recently elected Democratic governors and senators and almost going for Barack Obama in 2008. At press time, it was presumed that the state likely would not vote for Obama in the 2012 presidential elections, either, but the race would likely be close.

Impressions

I am in love with Montana. For other states I have admiration, respect, recognition, even some affection, but with Montana it is love, and it’s difficult to analyze love when you’re in it. . . . The scale is huge but not overpowering. The land is rich with grass and color, and the mountains are the kind I would create if mountains were ever put on my agenda.

—John Steinbeck, in Travels with Charley: In Search of America

Wyoming Dateline

18,000 b.c. Earliest evidence of humans in Wyoming.

a.d. 1807 John Colter explores the Yellowstone area, coming as far south as Jackson Hole.

1812 Fur trader Robert Stuart discovers South Pass, the gentlest route across the Northern Rockies.

1843 Pioneers begin traveling west on the Oregon Trail through Wyoming.

1848 The U.S. Army moves into Fort Laramie to protect Oregon Trail travelers from Indians.

1852 The first school in the state is founded at Fort Laramie.

1860 The Pony Express begins its run from Missouri to California, through Wyoming.

1867 The Union Pacific Railroad enters Wyoming.

1868 The Treaty of Fort Bridger creates the Shoshone Reservation in northwest Wyoming. The same year, the Territory of Wyoming is created by Congress.

1869 The Wyoming Territorial Legislature grants women the right to vote and hold elective office.

1870 Esther H. Morris becomes the nation’s first female justice of the peace.

1872 Yellowstone National Park is established as the nation’s first national park.

1884 The first oil well is drilled in Wyoming.

1886–87 A great blizzard decimates ranches of eastern Wyoming, sending many cattle barons into bankruptcy.

1889 The state constitution is adopted.

1890 Wyoming becomes the nation’s 44th state.

1892 The Johnson County War breaks out over a dispute about cattle rustling.

1897 The first Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo is staged.

1906 Devils Tower is established by President Theodore Roosevelt as the country’s first national monument.

1910 Buffalo Bill Dam is completed.

1925 Nellie Taylor Ross becomes the nation’s first female governor.

1927 A man claiming to be Butch Cassidy visits Wyoming from Washington, suggesting that the outlaw was not killed in Bolivia, as was generally believed.

1929 Grand Teton National Park is established, consisting of only the peaks. That same year, oil thefts are discovered on federal land at Teapot Dome, a scandal that rocks the Harding Administration.

1950 National forest and private lands are added to form Grand Teton National Park as it is today.

1965 Minuteman missile sites are completed near Cheyenne.

1973 The Arab oil embargo sends oil prices skyrocketing, instigating a huge oil-drilling boom in Wyoming.

1988 Five fires break out around Yellowstone National Park, blackening approximately one-third of the park.

1996 The National Park Service institutes a voluntary ban on climbing Devils Tower during June to respect American Indian religious ceremonies.

1998 Gay University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard is murdered.

2002 The $10-million National Historic Trails Center opens in Casper.

2004 The state enjoys a nearly $1-billion surplus in its annual budget, thanks to increased drilling and mining activity.

2006 The famed tram at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort closes.

2008 A new tram reopens at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort in time for the ski season.

2011 Two visitors are fatally mauled by grizzly bears in Yellowstone, the first such deaths in the park in more than 25 years.

Wyoming

In the Beginning

The earliest indications of man in what is now Wyoming date back some 20,000 years. No one knows the identity of these early inhabitants, nor can anyone say with certainty who created the Medicine Wheel in the Bighorn Mountains or the petroglyphs found in various parts of the state. The earliest identified settlers were the Crow, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho—tribes that came from the east—as well as the Shoshone and Bannock, who came from the Great Basin, more closely related to the peoples of Central America.

The lifestyles of these tribes were greatly changed by the arrival of two European innovations—the horse and the gun. The first white men in Wyoming were fur trappers, and the first of them was John Colter, who left the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806 to wander south through Yellowstone and possibly Jackson Hole.

Settlement (19th C.)

The Oregon Trail and other major pioneer routes west cut right through Wyoming and the territories of the Sioux, Shoshone, Arapaho, and other tribes. Without much regard for the people they were displacing, the non-Indians killed a great deal of the game the Indians depended on; Indian bands, in turn, harassed and sometimes attacked the travelers. Indian tribes were increasingly pushed west into tighter spaces, and there was warfare among tribes.

In a series of treaties, beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the tribes gave up rights to some of their homelands in return for reservations and other considerations. The discovery of gold in areas like the Black Hills and South Pass, and the routes of settlers, led to numerous treaty violations and continued conflict. Tribes in the east were being evicted and shipped west. Treaties that might have protected Indian rights were modified and broken, and U.S. Army troops were sent in to keep the peace. Some tribal leaders, recognizing the inexorable advance of the whites, decided the only alternative was to fight the invaders.

Trouble Between the Indians & the Settlers

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, of the Hunkpapa Sioux, joined forces with members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes along the Little Bighorn River. It was here in June 1876 that a huge gathering of Indians defeated George Custer and his men. Inevitably, this led to a backlash, a series of attacks on Indian communities, culminating in the death of Sitting Bull and the massacre of Spotted Elk and his Sioux followers in 1890 at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Chief Washakie of the Shoshone was one of the few great Indian leaders still alive, though his star was diminished by his decision to ally his tribe with the whites. That alliance got his people one of the finest reservations in the West, and the only one in Wyoming—Wind River. Then the U.S. Army moved the now-threadbare Arapaho, traditional enemies of the Shoshone, to Wind River “temporarily,” and the two tribes began an uncomfortable coexistence that continues to this day.

Industrialization & the 20th Century

Big cattle operators moved into Wyoming in the 19th century, controlling the territory’s economy and political scene through such organizations as the Cheyenne Social Club. A couple of severe winters in the 1880s and the influx of new settlers building fences raised tensions. When the cattle barons brought in hired guns to clear out the newcomers, the Johnson County War of 1892 erupted. The wealthy cattlemen claimed the newcomers were rustlers. But that show of muscle was futile in halting the longtime decline of the big livestock owners.

Since 1900, the energy industry has emerged as Wyoming’s primary industry. The Teapot Dome Scandal, which involved the bribery of federal officials for drilling rights in Wyoming, was one of the biggest political scandals of its day in the 1920s. The industrialization of public lands in increasingly remote areas of Wyoming in search of fossil fuels followed in subsequent decades, including the eastern side of the state, as well as the Pinedale area in western Wyoming.

The state’s remote areas became much easier to visit over the course of the 20th century. Rail and wagon travel dwindled. Airports arrived, along with interstates and other highways, making a Yellowstone vacation a more and more popular rite of road-trip passage.

Modern Wyoming

While agriculture has not faded away entirely in modern Wyoming, it has taken a backseat to the energy economy. Coal, oil, and natural gas are among the state’s top exports, as is atmospheric carbon: The state emits more carbon dioxide on a per-capita basis than any of its 49 peers.

In spite of the economic recession (or possibly because of it, in that Wyoming can definitely be visited on a budget), tourism continues to grow, as Yellowstone enjoyed a record-high number of visitors in 2010, followed by another banner year in 2011. This makes for a buoyant economy, but it also fuels more and more demand for sometimes scarce tourism facilities, as well as traffic jams and pollution.

Politically, Wyoming is known as one of the most conservative states, and many vocal locals say they want the federal government involved in their affairs as little as possible. However, with vast tracts of the state’s public lands under the purview of federal agencies, this is a sure recipe for controversy and conflict.

Local Notables: Famous Folks Who Have Called Montana & Wyoming Home

• Evel Knievel, daredevil, Butte, MT

• Dick Cheney, politician, Casper/Jackson, WY

• William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, scout/showman, Cody, WY

• Gary Cooper, actor, Helena/Bozeman, MT

• Dana Carvey, comedian, Missoula, MT

• David Lynch, filmmaker, Missoula, MT

• Ted Turner, media tycoon, Bozeman, MT

• Chet Huntley, journalist, Cardwell, MT

• Glenn Close, actress, Bozeman, MT

• Peter Fonda, actor, Livingston, MT

• Harrison Ford, actor, Jackson, WY

• Annie Proulx, writer, Saratoga, WY

Montana & Wyoming in Popular Culture

Books

In addition to the books discussed below, those planning an extended trip to Yellowstone and/or Grand Teton national parks will find an abundance of information in Frommer’s Yellowstone & Grand Teton National Parks (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

Fiction A. B. Guthrie’s The Big Sky (Houghton Mifflin, 1947) is now a Montana classic, as is Owen Wister’s The Virginian (Macmillan, 1929), set in frontier Wyoming. Then move on to contemporary fiction, like the classic fly-fishing novella A River Runs Through It (University of Chicago Press, 1976), by Norman Maclean. Fool’s Crow (Viking Penguin, 1986), by James Welch (a native Montanan), and Heart Mountain (Viking Penguin, 1989), by Gretel Ehrlich, are fictional stories that revolve around American-Indian and Asian characters. Annie Proulx’s Close Range: Wyoming Stories (Scribner, 1999) and Bad Dirt: Wyoming Stories 2 (Scribner, 2004) are recent additions by a fine writer who’s spent considerable time around Sheridan. Poet James Glavin’s beautifully written The Meadow (Henry Holt, 1992) is set in the Tie Siding area of southeast Wyoming.

Montana is fortunate to have the best of its literature compiled in one volume, The Last Best Place (University of Montana Press, 1988), the definitive anthology of Montana writings, from American-Indian myths to contemporary short stories.

Nonfiction Novelist Ivan Doig wrote a beautiful memoir about his youth in Montana, This House of Sky (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978). Gretel Ehrlich’s The Solace of Open Spaces (Viking Penguin, 1986) is a beautifully written, evocative account of Wyoming ranch life. Paul Schullery’s Searching for Yellowstone (Mariner Books, 1997) is a great look at the ecology of the world’s first national park and mankind’s impact on it. Eric Sorg’s Buffalo Bill: Myth and Reality is an informative read about the man who truly defined the mythos of the West.

If your interests lean more toward geography, check out the Roadside Geology of Montana (Mountain Press, 1986), by David Alt and Donald W. Hyndman, and the similar Roadside Geology of Wyoming (Mountain Press, 1988), by David R. Largeson and Darwin R. Spearing.

History Perhaps the best, and easiest, read about the history and culture of Montana is found between the covers of Montana, High, Wide and Handsome (University of Nebraska Press, 1983), written by Joseph Howard and first published in 1944. Another interesting historical tome is Aubrey Haines’s two-volume The Yellowstone Story (University Press of Colorado, 1977).

Films

Hollywood adapted Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It in 1992 with Brad Pitt; Rancho Deluxe (1975) is set in Livingston, Montana, and depicts a rapidly changing place through cattle rustlers played by Jeff Bridges and Sam Waterston; Little Big Man (1970) is a revisionist Western that covers Custer’s Last Stand and much more.

Wyoming films of note include the made-for-HBO The Laramie Project (2001), an adaptation of a stage play about the murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard; Shane (1953), the Western classic shot in Jackson Hole; Heaven’s Gate (1980), the Michael Cimino film about the Johnson County War whose title became synonymous with bloated Hollywood budgets; and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Steven Spielberg’s UFO epic that climaxes at Devils Tower National Monument. Brokeback Mountain (2005), the acclaimed adaptation of the Annie Proulx short story of the same name, took place in Montana and Wyoming, but most of the movie’s Rocky Mountain exteriors were actually shot in Canada.

TV

A number of 1950s and 1960s Western shows were set in Montana and Wyoming, including Buckskin (Montana) and Laramie, The Lawman, and The Virginian (Wyoming). The three national parks in Montana and Wyoming were covered in extensive detail in Ken Burns’s 2010 documentary series on national parks, which aired on PBS. However, the states have been ignored by most networks outside of PBS and Animal Planet in recent years.

Music

Country-and-western music is a favorite genre in Montana and Wyoming, but you will also see rock, blues, and jazz bands gracing the stages here. Showcasing primarily the twang of country music, Wyoming has its fair share of legendary music venues, like Cassie’s in Cody, Woods Landing near Laramie, and the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar and the Stagecoach in Jackson Hole.

Several well-known musicians have called this area home. Late country singer-songwriter Chris LeDoux lived on a ranch in Kaycee, Wyoming. Blackfeet singer-storyteller Jack Gladstone has been called “Montana’s troubadour.” Grunge-rock pioneers Bruce Fairweather of Mudhoney and Pearl Jam’s Jeff Ament both hail from Montana.

Eating & Drinking

Montana and Wyoming are probably best known for their beef, but you will also find a lot of local bison, elk, venison, and other game meats. (Some say Rocky Mountain oysters—deep-fried bull testicles—are a local specialty, but others disagree. They are widely available in both states.) Both states have some great trout streams, so be conscious of where yours originated; much of it comes from Idaho.

In Montana, huckleberries (purplish wild blueberries that resist commercial production) are a delicacy. Look for them growing wild alongside hiking trails in late summer or in everything from syrup to ice cream at souvenir stands. Northwest Montana also grows some other great crops, including cherries and numerous greens, but the biggest crop in the state is wheat, which means that you will find breads and other baked goods made from local wheat at the aptly named chain of Wheat Montana bakeries statewide.

Missoula and Bozeman are both great towns for foodies, as is Whitefish. In Wyoming, the best restaurants are undoubtedly in Jackson Hole, including the superlative cuisine at Jenny Lake Lodge in Grand Teton National Park. Montana’s Flathead Valley is probably the most fertile spot in either state, with cherry orchards and numerous organic farms.

There are a few wineries in Montana and numerous microbreweries in both states. Top Montana microbreweries include Bozeman Brewing Company, Big Sky Brewing Company and Kettle House Brewing Co. (Missoula), and Great Northern Brewing Company (Whitefish). Wyoming’s standout microbrewery is Snake River Brewing Co. in Jackson. These breweries produce a wide variety of beers, from Belgian whites to Scotch ales and dark stouts. Note that Montana enforces limited hours and a four-drink maximum at breweries across the state, and keep in mind that most Montana bars double as casinos with live and video poker and other games of chance.

Eating Native in the Flathead Valley

You will be hard-pressed to find people as fiercely devoted to locally produced food as residents of the Flathead Valley in northwestern Montana. Farms in the valley produce everything from goats to blueberries, and the popular farmers market in Whitefish offers up everything from tomatoes to squash, apples, and grapes. Local restaurants and bed-and-breakfasts such as Cafe Kandahar and the Garden Wall Inn serve local farm-to-table fare. FarmHands (www.whoisyourfarmer.org) offers a directory and map of local farms.

When to Go

Summer, autumn, and winter are the best times to visit the Northern Rockies. The days are sunny, the nights are clear, and the humidity is low. A popular song once romanticized “Springtime in the Rockies,” but that season—or what most people think of as springtime—lasts about 2 days in early June. The rest of the spring season is likely to be chilly with snow or rain; most of the annual moisture in these states falls during March and April.

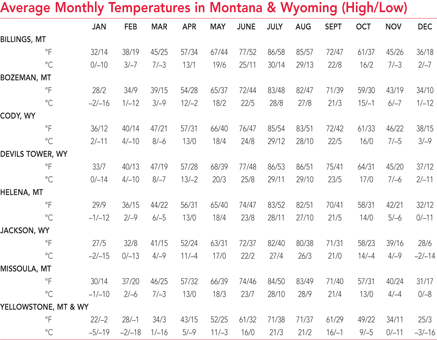

Summer is the best season to visit for hiking, fishing, camping, and wildlife-watching. It will be warm during the day and cool at night. In Montana, average highs in July run from 79°F (25°C) in West Yellowstone to 89°F (32°C) in Miles City; lows at night range from 38°F (3°C) to 60°F (16°C). In Wyoming, the average high temperatures in July range from 80°F (27°C) to 90°F (32°C)—at high elevations, it almost never gets above 100°F (38°C), and it’s dry. The plains tend to get hotter than the mountains.

Fall brings spectacularly clear days; cool, clear nights; and calm winds up until late October, when things get iffy again. Weather is changeable, however, and snow is possible—even likely—in the high country, so don’t try an extended backpacking trip unless you are experienced and well prepared. Actually, this is a requirement year-round; you can get caught in mountain snowstorms in July and August.

Winter is a glorious season here, though it can be very cold. Lows in Havre, Butte, West Yellowstone, and Jackson average single digits Fahrenheit (about –15°C) in January. And it can be very windy in some parts of these states, especially on the plains. But the air is crystalline, the snow is powdery, and the skiing is fantastic. If you drive around Montana and Wyoming in the winter, always carry sleeping bags, extra food, flashlights, and other safety gear. You need to be prepared to survive if your car breaks down or you get stuck in a blizzard or snow squall. Every resident has a horror story about being caught outside unprepared. Only the north entrance at Yellowstone National Park is open to automobiles in the winter. Lodging is available in the park only at Mammoth and Old Faithful. Ski resort towns, such as Jackson and Kalispell, stay lively all winter, but summer tourist towns, such as Cody, are quiet.

Holidays

Banks, government offices, post offices, and many stores, restaurants, and museums are closed on the following legal national holidays: January 1 (New Year’s Day), the third Monday in January (Martin Luther King, Jr., Day), the third Monday in February (Presidents’ Day), the last Monday in May (Memorial Day), July 4 (Independence Day), the first Monday in September (Labor Day), the second Monday in October (Columbus Day), November 11 (Veterans’ Day/Armistice Day), the fourth Thursday in November (Thanksgiving Day), and December 25 (Christmas). The Tuesday after the first Monday in November is Election Day, a federal government holiday in presidential election years (held every 4 years, and next in 2012).

Montana & Wyoming Calendar of Events

For an exhaustive list of events beyond those listed here, check http://events.frommers.com, where you’ll find a searchable, up-to-the-minute roster of what’s happening in cities all over the world.

January

Montana Pro Rodeo Circuit Finals. Montana’s best cowboys compete in the final round of this regional competition in Great Falls. Call  406222-5473 (www.montanaprorodeo.com) for information. Second or third weekend in January.

406222-5473 (www.montanaprorodeo.com) for information. Second or third weekend in January.

February

Winter Carnivals. In Whitefish, Montana, there is a parade, a hockey tournament, the “penguin plunge,” fireworks, and a dance. Call  406/862-3548 (www.whitefishwintercarnival.com). First weekend in February. Novelty ski races and other events take center stage during a similar Jackson, Wyoming, event. Call

406/862-3548 (www.whitefishwintercarnival.com). First weekend in February. Novelty ski races and other events take center stage during a similar Jackson, Wyoming, event. Call  307/733-3316. Mid-February.

307/733-3316. Mid-February.

Wyoming State Winter Fair. They hold this one indoors in Lander, except for the chariot races. There are booths galore, music, entertainment, a livestock competition, and a big dance. Browse www.wyomingstatewinterfair.org for more information. Late February or early March.

March

The Sale to Benefit the C. M. Russell Museum. This is the finest Western art auction in the country, with exhibitors and attendees from around the world. Great Falls, Montana. Call  406/727-8787 (www.cmrussell.org) for information. Mid-March.

406/727-8787 (www.cmrussell.org) for information. Mid-March.

St. Patrick’s Day in Butte. This wild and woolly (and often booze-soaked) outdoor party pays homage to Butte, Montana’s, Irish heritage. Call  406/723-3177 for more information. March 17.

406/723-3177 for more information. March 17.

April

Montana Storytelling Roundup. Thousands turn out for this annual celebration of storytelling in Cut Bank, Montana. Call  406/873-0276 (www.montanastorytellersroundup.com) for the schedule. Late April.

406/873-0276 (www.montanastorytellersroundup.com) for the schedule. Late April.

May

International Wildlife Film Festival. This unique, juried film competition in Missoula, Montana, has more than 100 entries from leading wildlife filmmakers. Call  406/728-9380 (www.wildlifefilms.org). Early to mid-May.

406/728-9380 (www.wildlifefilms.org). Early to mid-May.

Miles City Bucking Horse Sale. A “3-day cowboy Mardi Gras,” this stock sale in Miles City, Montana, features street dances, parades, barbecues, and, of course, lots of bucking broncos. Call  406/234-2890 (www.buckinghorsesale.com) for information. Third weekend in May.

406/234-2890 (www.buckinghorsesale.com) for information. Third weekend in May.

Elk Antler Auction. Nearly 10,000 pounds of bull-elk antlers are auctioned off in Jackson’s town square. Call  307/733-3316 (www.jacksonholechamber.com or www.elkfest.org) for information. Third Saturday in May.

307/733-3316 (www.jacksonholechamber.com or www.elkfest.org) for information. Third Saturday in May.

June

Plains Indian Museum Powwow. Indian dancers from around the region compete in various dance categories, accompanied by traditional drum groups, on the Robbie Powwow Garden next to the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. Call  307/587-4771 (www.bbhc.org) for information. Mid- to late June.

307/587-4771 (www.bbhc.org) for information. Mid- to late June.

Chugwater Chili Cook-Off. Thousands of hot-food pilgrims come to Chugwater, Wyoming, to taste the spicy contenders in this contest. Call  307/422-3345 (www.chugwaterchilicookoff.com) for information. Mid- to late June.

307/422-3345 (www.chugwaterchilicookoff.com) for information. Mid- to late June.

Lewis & Clark Festival. Commemoration of Lewis and Clark’s journey in and around Great Falls, Montana, with historical reenactments, buffalo roasts, and float trips. Call  406/452-5661 for information. Late June.

406/452-5661 for information. Late June.

Eastern Shoshone Indian Days Powwow. A celebration of American-Indian tradition and culture that’s followed by one of Wyoming’s largest powwows and all-Indian rodeos, in Fort Washakie, Wyoming. Call  307/332-9106 (www.easternshoshone.net) for information. Late June.

307/332-9106 (www.easternshoshone.net) for information. Late June.

July

Cody Stampede. There are rodeo nights all summer in Cody, but this long weekend is the big one, and the rodeo ring excitement carries over to street dances, fireworks, and food. Call  800/207-0744 (www.codystampederodeo.com) for details. July 1 to July 4.

800/207-0744 (www.codystampederodeo.com) for details. July 1 to July 4.

Legend of Rawhide Reenactment. An overeager gold miner comes to an untimely end in this production of the popular Western legend in Lusk, Wyoming. Call  800/223-5875 (www.legendofrawhide.com) for information. Second weekend in July.

800/223-5875 (www.legendofrawhide.com) for information. Second weekend in July.

International Climbers Festival. Speakers, music, demonstrations, and climbing at the famed Wild Iris and other rock faces in Fremont County attract rock climbers from around the world to this gathering in Lander, Wyoming. Call  3443/878-3779 (www.climbersfestival.org). Second weekend in July.

3443/878-3779 (www.climbersfestival.org). Second weekend in July.

North American Indian Days. The Blackfeet Reservation hosts a weekend of native dancing, singing, and drumming, with crafts booths and games, in Browning, Montana. Call  406/338-2344 for information. Mid-July.

406/338-2344 for information. Mid-July.

Grand Teton Music Festival. Fine musicians from around the world join this orchestra every summer. A varied classical repertoire includes numerous chamber concerts and some premieres in Teton Village, Wyoming. Call  307/733-3050 (www.gtmf.org) for information. Mid-July to the end of August.

307/733-3050 (www.gtmf.org) for information. Mid-July to the end of August.

Cheyenne Frontier Days. One of the country’s most popular rodeos, the “Daddy of ’em All” entertains huge crowds for a full week in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Call  800/227-6336 (www.cfdrodeo.com) for information. Last week in July.

800/227-6336 (www.cfdrodeo.com) for information. Last week in July.

Evel Knievel Days. Butte, Montana honors its favorite son and one-time problem child, late daredevil Evel Knievel, with parades, stunt shows, and children’s events. Call  406/723-3177 (www.knieveldays.com) for more information. Last week in July.

406/723-3177 (www.knieveldays.com) for more information. Last week in July.

August

Sweet Pea Festival. This full-fledged arts festival in Bozeman, Montana, with fine art and musicians, has varied entertainment for all ages. Call  406/586-4003 (www.sweetpeafestival.org) for information. First full weekend in August.

406/586-4003 (www.sweetpeafestival.org) for information. First full weekend in August.

Grand Targhee Bluegrass Festival. This 3-day celebration of music, arts, food, and entertainment is held at Grand Targhee Resort, near Jackson, Wyoming. Call  800/827-4433 (www.grandtarghee.com) for information. Mid-August.

800/827-4433 (www.grandtarghee.com) for information. Mid-August.

Crow Fair. This festival is by far one of the biggest and best American-Indian gatherings in the Northwest, with dancing, food, and crafts in Crow Agency, Montana. Call  406/638-3700 (http://crowfair.crowtribe.com) for information. Mid-August.

406/638-3700 (http://crowfair.crowtribe.com) for information. Mid-August.

Montana Cowboy Poetry Gathering. This 3-day event features readings and entertainment from the real McCoys in Lewistown, Montana. Call  406/538-4575 (www.montanacowboypoetrygathering.com) for information. Mid-August.

406/538-4575 (www.montanacowboypoetrygathering.com) for information. Mid-August.

September

Nordicfest. This Scandinavian celebration in Libby, Montana, features a parade, a juried crafts show, headliner entertainment, and an international Fjord horse show. Call  800/785-6541 (www.libbynordicfest.org) for information. First weekend following Labor Day.

800/785-6541 (www.libbynordicfest.org) for information. First weekend following Labor Day.

Western Design Conference. Western-style furniture and clothing fashions are displayed on the runway in Cody, Wyoming. Call  307/690-9719 (www.westerndesignconference.com) for more information. Early or mid-September.

307/690-9719 (www.westerndesignconference.com) for more information. Early or mid-September.

Buffalo Bill Historical Center Art Show and Patrons Ball. With a big art sale to support the museum and a black-tie dinner and ball, this is one of the Rockies’ premier (and only) formal social events, in Jackson, Wyoming. For information, call  307/587-4471 (www.bbhc.org). Late September.

307/587-4471 (www.bbhc.org). Late September.

October

Hatch. Unspooling over 6 days, this creative arts festival in Bozeman includes film screenings, workshops, filmmaker Q&As, and live music after dark. For information, call  406/699-7642 (www.hatchexperience.com). Early October.

406/699-7642 (www.hatchexperience.com). Early October.

Glacier Jazz Stampede. This 4-day event brings ragtime, swing, and blues musicians to multiple venues in Kalispell, Montana. Call  406/755-6088 (www.glacierjazzstampede.com) for more information. Early October.

406/755-6088 (www.glacierjazzstampede.com) for more information. Early October.

December

Christmas Strolls and Parades. Statewide, Montana and Wyoming. Check with local chambers of commerce for specific dates and locations.

Lay of the Land

In Montana and Wyoming, the earth seems to have turned itself inside out, its hot insides leaking into hot springs and geysers, its bony spine thrust right through the skin of the continent to form the Continental Divide, making it a geologist’s dream. And to a biologist, it’s heaven, one of the last regions in the United States with enough open space for animals like elk and grizzly bears to roam free.

Plains, basin, and range alternate in this high-altitude environment that is in large part defined by its extremes of weather and climate. These changing landscapes make Montana and Wyoming two of the best vacation spots in the country for travelers who like their scenery dynamic and dramatic.

The western side of both states is mountainous, dragging moisture from the clouds moving west to east and storing it in snowpack and alpine lakes. Because the ridge of the Rockies wrings moisture from the atmosphere, you find deeper, denser forest extending far to the west, while on the east side, the lodgepole pine, spruce, and fir forests give way to the Great Plains, a vast, flat land characterized by sagebrush, native grasses, and cottonwood-lined river bottoms.

But a lot of the landscape dates back more than 100 million years to when the collision of tectonic plates buckled the Earth’s crust and thrust these mountains upward. Later, glaciers (of which some vestiges remain) carved the canyons. The tallest peaks in Wyoming are located within the Wind River Range, which rises from the high plains of South Pass and runs northwest to the Yellowstone Plateau. Nine of the peaks in the Winds have elevations over 13,000 feet; Gannett Peak, at 13,809 feet, is the highest in the state. Several other mountain ranges are found to the south of Yellowstone—including the Absarokas and the stunning Tetons—and from Yellowstone north into Montana run other dramatic ranges, including the Gallatin, Madison, Mission, Bitterroot, Cabinet, and Beartooth, where you’ll find Montana’s highest point, Granite Peak, at 12,807 feet.

The Continental Divide enters Montana from Canada and traces a snaking path through the two states. Both Montana and Wyoming have rivers flowing west to the Pacific and east to the Atlantic.

Yellowstone’s Latent Supervolcano

In 2009 and 2010, swarms of earthquakes on the floor of Yellowstone Lake shook the geological community, raising the specter of an eruption on the magnitude of a supervolcano: thousands of times larger than typical eruptions. The Yellowstone caldera has erupted in similarly big ways every 600,000 years for the past 2 million years, and it’s about due any century now. However, the hype has a way of overshadowing geological reality: The caldera that sits atop the hotspot responsible for such massive eruptions is not currently anywhere hot enough to produce a cataclysmic blowout like the ones that occurred in eons past. A small eruption could take place at any time, but there will be plenty of warning (in the form of scientific data) before the big one.

Here you’ll also find the headwaters of major river systems—the Flathead and Clark Fork heading west into the Columbia from Montana, along with the Snake from Wyoming; the Yellowstone, North Platte, and Madison joining the Missouri bound east; and the Green from Wyoming emptying into the Colorado heading south. These rivers are the lifeblood of the region, supplying irrigation, fisheries, and power from dams. Montana also boasts the country’s largest freshwater body of water west of the Mississippi River: Flathead Lake. Yellowstone and Jackson lakes are Wyoming’s two largest natural bodies of water.

Montana is the greener of these two states, with more abundant alpine wilderness and bigger rivers. Wyoming, however, has been dealt a more interesting hand of natural wonders: waterfalls, geysers, and other geothermal oddities at Yellowstone, as well as the natural landmark of clustered rock columns that rise more than 1,280 feet above the surrounding plains at Devils Tower National Monument, near the state’s Black Hills region of the northeast. At Wyoming’s Red Desert, south of Lander, the Continental Divide splits to form an enclosed basin where no water can escape, and nearby you find Fossil Butte National Monument, an archaeological treasure chest of fossilized fish and ancient miniature horses.

The states are characterized by long, cold winters and short summers of hot days and chilly nights. Temperature ranges are dramatic and are largely dependent on elevation. Except along the far western edge of Montana, precipitation here is less than 30 inches a year. It’s considerably less as you journey east and south. But the snowpack in the high mountains—more than 300 inches accumulate in some areas—melts through the summer and keeps the rivers running.

Responsible Travel

The perpetual debate continues throughout Montana and Wyoming: natural gas drilling and mineral extraction versus recreation and conservation. The Pinedale anticline south of Jackson Hole in Wyoming has been heavily drilled for gas in recent years, sometimes marring the once crystalline Teton views. The Berkeley Pit in Butte, Montana, is a stark reminder of the price to be paid, a mile-long gash in the earth where a copper-rich mountain once stood.

Numerous lodgings in both states have initiated procedures to be greener, from recycling to water conservation programs. At Teton Village in Wyoming, Hotel Terra (www.hotelterrajacksonhole.com;  800/631-6281) is the first LEED-certified hotel in the state.

800/631-6281) is the first LEED-certified hotel in the state.

The “localvore” movement is especially strong in Montana in Whitefish, Missoula, and Bozeman.

In Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, heavy summer auto traffic and the annual impact of millions of human beings have raised questions about the sustainability of these national parks. But a visit to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks can be a relatively green vacation. In Yellowstone, concessionaire Xanterra Parks & Resorts (www.yellowstonenationalparklodges.com;  866/439-7375 or 307/344-7311) has implemented numerous environmental initiatives, including a recycling program, sourcing seafood from sustainable fisheries, and encouraging guests to reuse towels and conserve heat. Campgrounds have recycling bins near the entrance. In Grand Teton, the Grand Teton Lodge Company (www.gtlc.com;

866/439-7375 or 307/344-7311) has implemented numerous environmental initiatives, including a recycling program, sourcing seafood from sustainable fisheries, and encouraging guests to reuse towels and conserve heat. Campgrounds have recycling bins near the entrance. In Grand Teton, the Grand Teton Lodge Company (www.gtlc.com;  800/628-9988 or 307/543-2811) has also implemented very successful sustainability programs to lessen the human impact on the park. The company purchased wind credits to offset its energy use and diverted 50% of its waste into reusing and recycling everything from aluminum cans, to horse manure, to food waste.

800/628-9988 or 307/543-2811) has also implemented very successful sustainability programs to lessen the human impact on the park. The company purchased wind credits to offset its energy use and diverted 50% of its waste into reusing and recycling everything from aluminum cans, to horse manure, to food waste.

When visiting the national parks of Montana and Wyoming, try to use public or shared transportation whenever possible and minimize the amount of garbage you leave in the park trashcans. Hike as much as possible; you actually get to enjoy the views, and it’s one less car on the usually strained roads. One of the best ways to lessen one’s impact is to go off the grid on an overnight backpacking trip. Leave No Trace (www.lnt.org) is the backpacker’s ethic to leave any campsite in the same condition—or better—than when one found it. Backpacking is a refreshing counterpoint to modern life that will give perspective on the issues of sustainability and personal energy dependence.

In addition to the resources for Montana & Wyoming listed above, see frommers.com/planning for more tips on responsible travel.