TWO

Think about the time it took to prepare for your last camping trip—how long it took you to plan and pack for a weekend of sleeping in tents and cooking over campfires. Now imagine you’re doing it for two weeks following an earthquake.

Preparing for a natural disaster of this magnitude will take time. You need to be ready for more than just a weekend of “roughing it.” Forget all the advice you’ve heard about three-day kits and being able to be on your own for seventy-two hours: that works to meet your needs after a windstorm, flood, or snow event, where help will arrive within three days or less, but not for a full-rip Cascadia earthquake. You must understand that help is not coming soon. Not in three days. Not in five days. The earthquake will break our roads and bridges, kneecap our hospitals, and rupture the power, sewer, and water systems. Local first responders will be overwhelmed by the level of need and the difficulty of communication and movement. Getting help from outside with the interruptions of transportation and communication will be a long, slow process. Assume outside aid will take up to two weeks to reach you, even longer in remote areas.

THE CASCADIA RISING EXPERIMENT

In June 2016, more than 20,000 disaster professionals in the region participated in a drill to practice confronting a 9.0 Cascadia earthquake in a simulation called Cascadia Rising. Despite a massive mobilization of resources, the overall results were unambiguous: getting outside help to most people in the region would take up to two weeks. Two weeks without power, plumbing, water, phones, or internet. Two weeks with limited public services or medical assistance. Two weeks when residents would need to take care of themselves.

The people who will respond to a mega-earthquake worked to exhaustion during the experiment. The exercise was a simulation; their stress was real. They will go to heroic lengths to get help to anyone who needs it after the Cascadia earthquake, but responders are not ready to launch a twenty-first-century response in 1850 conditions. Supplies will trickle in slowly—no Amazon next-day delivery—and moving people will be even slower. Hundreds of millions of cell phone calls, emails, and texts in our region will have to transform into whatever amateur (ham) radio traffic, battery-operated radios, bullhorns, walkie-talkies, satellite phones, and note-carrying couriers can pass along. Responders will eventually overcome these limitations, but it will take longer than anyone wants it to.

OFFICIAL ENDORSEMENT OF TWO-WEEKS-READY

Partly as a result of the Cascadia Rising exercise, the Cascadia impact zone is the only region where government officials have adopted a standard of two-weeks-ready. Even Alaska advises residents to have only seven days’ worth of supplies—because, unlike our region, Alaskans have living memory of a 9.2 earthquake in 1964. With Alaska’s building codes and infrastructure systems reflecting that, individual preparedness isn’t as critical.

Despite the need to be two-weeks-ready, there is good news. While the wait will be long for outside help to arrive, you can expect assistance immediately from the people who are near you when the earthquake comes. Media reports of heroic group efforts in disasters, organized and carried out by ordinary people, usually attribute the actions to a uniquely courageous or generous spirit of the people in that area, but these reports follow disasters in every part of the world. There is nothing unique or even unusual about people going to astonishing lengths to help each other in dire circumstances.

BARRIERS TO A QUICK RESPONSE

We’ve all seen pictures of total devastation from earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, or tornadoes, and we’ve seen that in our country, assistance usually arrives within a few hours or days. But this earthquake will be different.

Most disasters cause damage over less than an entire region. Neighboring counties and states are largely unaffected and able to quickly offer supplies and personnel to the impacted jurisdictions. In the case of hurricanes and flooding, there is often advance warning of the disaster. Needed equipment, work crews, and supplies are moving toward the disaster area even before it has been hit.

A 9.0 Cascadia earthquake will cause widespread destruction from severe shaking and tsunami impacts. There will be damage across parts of three states and into British Columbia, Canada. There will be severe shaking in areas west of I-5, causing considerable damage in Eureka, California; Medford, Eugene, Salem, and Portland, Oregon; Vancouver, Tacoma, Olympia, Seattle, and Bellingham, Washington; and Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. I think of this as the severe shake zone, though there will be great variation across this vast area in the intensity of shaking and not all locations will be devastated. Areas east of I-5 will also be impacted, with damage varying widely based on quality of building construction, soils under structures, and distance from the earthquake epicenter.

Limited assistance can be expected from the largely rural areas directly to the east, north, and south of the severe shake zone, as officials in these areas simply won’t have the range of personnel or equipment that will be needed to cover an unprecedented level of disaster. Many critical resources will come from far away, and that takes time.

Supply lines branching out from Seattle, Portland, and other ports on the West Coast between Northern California and Vancouver Island will be severed by the earthquake. City and county officials outside the severe shake zone, desperate to supply help to earthquake victims, will simultaneously need to figure out how to provide their own residents with food, medicine, fuel, and other critical items. Even Alaska, which receives most of its supplies from Seattle, will be scrambling to meet basic needs.

Most grocery stores, pharmacies, and similar suppliers use “just-in-time” inventory practices that bring in goods as they need them rather than stocking up. This means that few communities will have more than a three-day supply. Ongoing aftershocks, limited fuel supplies, and worst-case communication issues will complicate opening routes into the impact zone. Structural damage to roads, downed bridges, and massive landslides will slow progress even further.

Ships will be immediately deployed to the coast but it will take days or weeks for them to arrive. Also, the entire coastline near the rupture will be redefined, making existing charts useless and navigation dangerous. While a maritime response will help people on the coast, there won’t be an efficient way to push supplies east over the Coast Range and into more populated areas.

Similarly, the logistical challenges and risks to dropping supplies from airplanes make it completely impractical for most of the needs the region will face. Drones may be an option for limited use but, again, don’t currently offer a realistic option for meeting large-scale need.

FUELING UP

Recovery efforts need fuel: With roads blocked and bridges down, getting fuel will be difficult, but without fuel the heavy equipment to clear roads can’t work. Without clear roads, utility crews will not be able to restore power. Without the power that medical and other critical services need to fully function and that will restore cell phone communication, coordinating response and repair efforts will be unimaginably slow and difficult. Besides road clearing, fuel will be needed to keep hospital and other life-saving generators running, evacuate patients, pump fuel from underground tanks, open shelters, and transport supplies.

More than 90 percent of the liquid fuel supply for Oregon is held in the fuel depot in Portland, where only a handful of tanks are built to withstand a strong seismic event. Even if the tanks were designed for a major earthquake, the soil the tanks sit on will turn into a mushy mess due to ground liquefaction, resulting in tipped tanks and lost fuel. While Oregon’s fuel situation will be especially dire, the entire region will struggle to get the fuel needed for response efforts.

GETTING STARTED

While getting ready isn’t easy, almost everyone already has at least a few items they’ll need. Folks who are avid campers might already be halfway to ready because of the supplies they have on hand.

Regardless of how prepared you are now, it’s nice to know that every step you take toward preparedness counts. You don’t have to do everything; you just must do something. Once you start, keep going. It might take you a few months or a few years. You may spend a little money or a lot.

Start small. The chapters in this book are prioritized based on the most important items for your health and safety. For example, addressing hazards in your home now will help prevent injuries during a mega-earthquake. Having water will be the single most critical thing you can do to get ready. Move through the chapters in order since the most important survival needs are addressed in the first few chapters.

Most people try to do too much too soon. That means thinking about the Cascadia earthquake a lot, which is deeply unsettling. It can be overwhelming as your mind leaps and spins beyond solvable problems to the most difficult quandaries: What if I’m on the other side of the river from my family and the bridge collapses? What if I’m at work and home is sixty miles away? What if I have a medical condition and the lack of electricity means I can’t get life-saving treatment? These are important problems to solve, but they aren’t the ones to tackle first. Start with what is simple and straightforward. Work up to what is complicated and hard.

It may help to initially assume that you’ll be home with your loved ones when the earthquake comes. For many of us, our hours at home are nearly half of each day, so this is not a ridiculous proposition. Begin your preparations using an earthquake scenario in which your loved ones are together and medical needs are manageable.

Working on household preparedness may not get you much appreciation or support. If you aren’t getting active resistance, don’t slow down your efforts. Go back to why this is important to you. Focus on that. Find others you can connect with who feel as you do about getting ready. On the days the journey is difficult, just imagine your family warm, dry, fed, and safe after the earthquake. Then picture the profuse apologies they’ll offer for ever making fun of your efforts to get ready!

AIM FOR “GOOD ENOUGH”

It is impossible to be perfectly prepared. What you need will be different if the earthquake comes on the second Tuesday of August at noon than if it comes on the first Saturday of January at midnight. Accounting for all possibilities is a fool’s game, and people abandon projects every day because they can’t complete them as perfectly as they’d like. There is no single right path—so much depends on where you live, who is in your household, the likely services in your area. The best thing to do is accept that your preparations can’t account for every situation. Don’t let that distract you or stop you.

The “Necessary” items on the lists of supplies in the checklist at the end of each chapter are those that are most important to health and safety. The “Nice to Have” items are those that will enhance your comfort in post-earthquake conditions. You could survive without all the necessary items, and you could be comfortable without any of the additions from the “Nice to Have” lists. You’ll likely be fine even if you work through the lists haphazardly, skipping many items. The exception to this is water. Don’t skip it and don’t delay ensuring your supply in whichever form you decide on.

SUGGESTED SCHEDULE

Some people will prefer to get the entire list of necessary supplies for each chapter before moving on to the next. For those who want to be at least somewhat ready in all areas, follow this monthly schedule to get as far as you can and then repeat until you are two-weeks-ready:

Month 1: Read this book and determine your “why.” Write it down and look at it often.

Month 2: Get your house ready.

Month 3: Assemble your water supply.

Month 4: Prepare a go-bag.

Month 5: Work on your family plan.

Month 6: Assemble first aid, health, and safety supplies.

Month 7: Assemble hygiene and sanitation supplies.

Month 8: Assemble shelter, clothing, and bedding.

Month 9: Address your household’s special needs.

Month 10: Assemble food and food preparation supplies.

Month 11: Compile communication and preparedness folder.

Month 12: Review what you’ve done and what you’ve learned. Celebrate progress and set goals for next year.

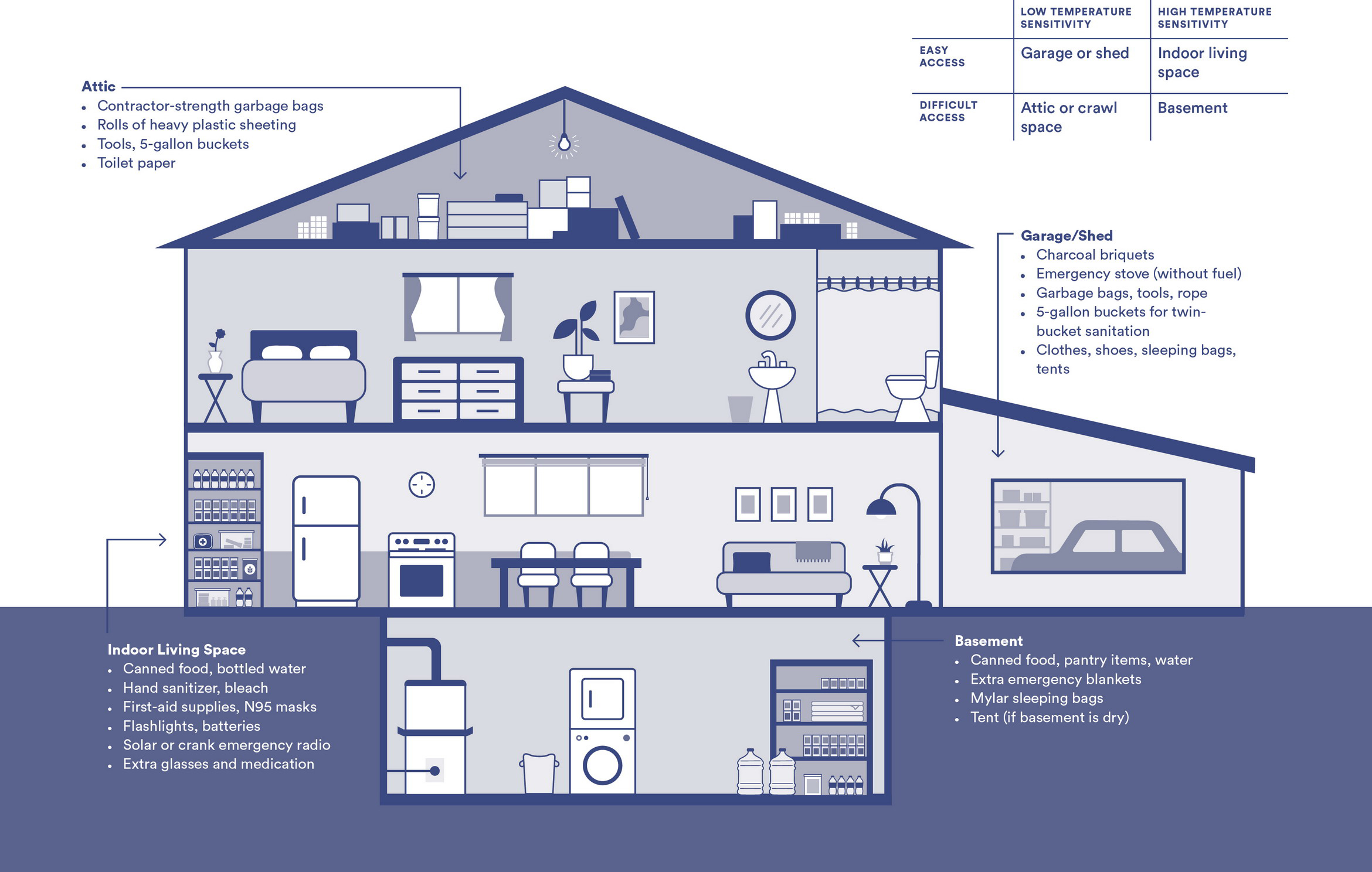

STORAGE IDEAS IN THE HOUSE

Canned water and food fits under beds, low sofas, and chairs; push it far enough under to hide. You can also use the back of shelves in a linen closet, kitchen cabinets, and bathroom cabinets.

Cans of food for long-term storage may fit behind books on deep bookshelves.

Flashlights, toilet bags, or other small items can be stored in hollow ottomans and stools.

Cases of canned seltzer water fit behind most bathroom-cabinet pipes.

Cases of canned water can line a closet floor, but store only light items like shoes on top. Food and water can also be stored on small shelves underneath hanging rods in a closet.

Contractor-strength garbage bags, blankets, or sleeping bags can be stored between a mattress and box springs.

Large containers of long-term food (no. 10 cans or plastic buckets) can be stacked and secured, covered with fabric, and used as an end table.

WHERE TO STORE SUPPLIES

Short of hiring a structural engineer to survey your home and make recommendations, there is no right answer to the question of where to store supplies. Wood-frame buildings generally perform well in an earthquake due to the flexibility of the structure. However, a four- to six-minute 9.0 earthquake is longer and stronger than the earthquakes this observation is based on.

How well your dwelling will do in an earthquake depends on the soil it sits on, whether it is on an unstable slope, the method of building construction, building codes in place during construction, the number and strength of interior walls, whether it is bolted to the foundation, and the integrity of structures nearby. Unreinforced-masonry buildings will do poorly in a Cascadia event, as will homes on steep slopes subject to slides. Trees falling and blocking access to your house, garage, or sheds may be less of a problem than you imagine, as they are generally flexible enough to sway wildly but not fall in earthquakes. However, if the soil under the tree is not stable, then the tree won’t be, either.

Some emergency officials recommend storing all your emergency supplies in the garage, on the assumption that having everything in one place is better than trying to collect items from several locations. Also, it is likely you’ll be able to get supplies out of a garage, since most are wood framed and unlikely to completely collapse. On the other hand, the temperature extremes in many garages means that supplies such as food and medicines will degrade quickly if stored there. Basements are ideal for storing food and water, but access could be an issue.

If you live in a small apartment, condo, or house, your options are limited. Do the best you can, prioritizing water, a go-bag (see this page), and shelter. Consider asking to store supplies at the house or apartment of a friend who has more space and lives within walking distance.

PREPAREDNESS EXPENSES

You could think of the Cascadia earthquake as transporting you to a place no one wants to visit for a two-week experience no one wants to have. As for any getaway, you’ll need to cover the costs of lodging, clothing, food, and beverages. The same strategies you use to set aside money for out-of-the-ordinary expenses like vacations, wedding gifts, or car repairs can be used to establish an earthquake-preparedness fund.

Another option is to add preparedness items to your ordinary shopping list based on what your budget can stretch to cover. Most people find they are more successful buying supplies at a slow and steady pace than trying to purchase large amounts of what they need all at once.

If you have little money, it will take you longer to prepare, but it is still possible. Ask for preparedness items as gifts from loved ones or from “buy nothing” social media groups. Shop garage sales and thrift shops. Remember that water, the most critical need you’ll have, is free if you just fill clean empty soda bottles and rotate them every six months.

PREPAREDNESS ITEMS EASILY FOUND AT GARAGE SALES AND THRIFT SHOPS

Hard hats, bicycle helmets

Warm (especially wool and synthetic) non-cotton clothing and coats

Pet carriers and crates

Foam mats for sleeping pads

Filing cabinets and ice chests to store supplies

Golf-bag carts, strollers, wagons, and wheeled suitcases to move supplies

Camping equipment, including tents

Cast-iron cookware

Wool blankets

First-aid and wilderness survival books