OCTOBER 1944 - MAY 1945

THE NEW U-BOAT ARM TAKES SHAPE

458. Effect of the loss of the Atlantic bases

“… 15.9.44. Now that the French Atlantic ports are no longer in our possession, U-boat operations will be continued from Norway. A few Home ports will also be used, since the Norwegian bases have insufficient accommodation, and operational possibilities will thus be limited. The Type IXC boats will no longer be able to operate either in the Caribbean or on the Gold Coast without refuelling, and will therefore be obliged to concentrate mainly on the US coast, the Newfoundland area and also the St Lawrence, which is again accessible to schnorkel boats. As a rule we shall be unable to use the Type VIIC boats in the Channel, since the passage takes so long that they would be unlikely to arrive in a fit state to operate under such difficult conditions; the only other areas remaining to them are the Moray Firth, the Minch and the North Channel in British coastal waters, and Reykjavik.

“It must be assumed that the enemy will concentrate his A/S forces off Norway, and in the Atlantic passage, North Sea and Baltic approaches. Theoretically, he can build up such heavy concentration in these regions that the old-type boats, which need to schnorkel fairly often, are bound to be located sooner or later and subjected to a concerted attack. Hence, if it were necessary to continue the campaign with these old types, the loss of the Atlantic bases would prove to be grave and decisive; but the new Type XXI boats, by virtue of their very great endurance, high submerged speed and deep diving capability, should be able to thrust their way through the enemy A/S concentrations to operate successfully both in the North Atlantic and in remote areas…” (389).

This brief statement outlined the U-boat situation as FO U-boats saw it at the beginning of October 1944, irrespective of the general course of the war; and in order to understand his apparent confidence in the future success of the new-type boats, it would be well at this point, to examine the provisions of the 1943 Fleet Building Programme, in so far as they affected the U-boat (390).

459. The Central Shipbuilding Committee and the new building programme

In their original building proposals of July 1943, the German Naval Command envisaged the completion of the first two Type XXI U-boats in November and December 1944, with trials in the spring of 1945, after which serial delivery would gradually accelerate to 30 boats a month by the autumn. This programme presupposed that the Armaments Ministry was prepared to provide all the requisite building facilities and that work would proceed undisturbed by air raids and free of bottlenecks. Dönitz, who regarded it as completely inadequate, asked Speer to submit counterproposals; in reply, Speer promised to have the first boat completed in April 1944 and then to start serial production without trials, provided that the Type XXI programme was accorded priority over all other naval construction and that it proved possible to build the boats on prefabricated and mass-production principles. The eminent U-boat constructor Schürer saw no fundamental objection to this last proviso and Dönitz, in view of the immense amount of time that would so be saved, accepted Speer’s proposal.

The task of winding up the previous naval construction programme and of implementing the new was taken over, in the summer of 1943, by the so-called Central Shipbuilding Committee, composed of representatives from both the Naval Command and the Armaments Ministry and on whose instructions planning of the new boats commenced at the Glückauf Construction Office, Blankenburg. In the Autumn of 1943 the first orders were placed with German firms for U-boat batteries, pressure-hull sections etc., on 8th December of that year the constructional drawings were completed, and on 1st January 1944 the new naval building programme was first submitted for approval. The U-boat programme provided for the completion of the first Type XXI boat in April 1944 - as had been agreed with Speer in the summer of 1943 - and the remainder of the series of 30 boats by July. The first Type XXIII boat was to be completed in February 1944, with serial delivery of another 19 commencing in April (391).

460. The U-boat building programme taxes German productive capacity

A major barrier to successful implementation of the overall U-boat building programme lay in a dual requirement for both rapid achievement of mass production of the new boats and maintenance of the rate of delivery of the older types, which necessitated provision of double the quantity of materials and manufacturing capacity over a transition period of from six to eight months. One of the prime essentials was to step up the production of U-boat batteries, and to achieve this in the short time available before the new boats began to arrive from the builders was the Armaments Ministry’s most difficult task; no plant for the manufacture of batteries existed in Germany itself, so it was necessary to produce the requisite machinery and equipment for this at the expense of current contracts, except those concerned with aircraft production, which had absolute priority. An additional problem, which at first appeared insoluble, was posed by the sheer quantity of lead and rubber needed for the batteries; but this difficulty was later overcome.

The new boats had also to be equipped with very powerful electric motors and a large number of other electrical fittings, such as cruising motors, trimming and bilge pumps, echo-ranging gear, underwater listening apparatus, radio and radar sets and radar search receivers, production of which engaged a considerable part of the whole German electrical industry and was only made possible by severe curtailment of such essential work as power-station and locomotive construction.

The provision of high-grade steel plate for the pressure hulls posed another difficult problem, for this commodity constituted the worst bottleneck in the whole of the steel industry and, since the old-type boats had still to be built and the new types required even more, demand for steel plate from the autumn of 1943 was three and a half times as great as the allocation hitherto. Furthermore, because of a heavy requirement for the repair of bomb damage to warships and local installations, the dockyards, already burdened with the expanded naval building programme, were now unable to cope with the shaping of pressure-hull sections, which had therefore to be delivered ready rolled.

The Chairman of the Central Shipbuilding Committee, Herr Merker, had taken on a difficult task. Considerable risk was involved in mass-producing a fundamentally new type of U-boat without trials, for if the boat proved to be a failure, the prodigious efforts of German industry would have been in vain and material allocated for the construction of 180 to 200 U-boats would have become so much scrap. Just as great a risk was involved in the introduction of prefabrication and mass-production methods into general shipbuilding; both methods were being applied for the first time to craft of considerable size under severe wartime conditions and against the advice of many experts, while those responsible were beset by the worry of completing the task at the earliest possible date. Nevertheless, contracts were placed with German yards for 360 Type XXI and 118 Type XXIII, and in the Mediterranean ports for 90 Type XXIII U-boats.

461. Prefabrication and mass production

The hull of the Type XXI U-boat was made up of eight separate sections - one section to a compartment - and these sections were constructed in 13 different yards, which allowed duplication and ensured that if a number of sections were destroyed in one yard a corresponding number of U-boats would not be lost. Nevertheless, the safety of the section-building and U-boat assembly yards was a matter of much concern, and in 1944 efforts were made to provide them all with bunker protection, a step already in hand at Hamburg-Finkenwerder and Bremen-Farge, with a few others being improvised elsewhere. The situation would have been less critical if section building could have been moved inland; but this was impossible as, owing to their size, the sections could only be transported to the assembly yards by water.

The actual building process was roughly as follows. A section-building yard was supplied first with, say, 40 similar part-sections of section 1 - the stern section of the boat - and delivery of the remaining part-sections was then timed to ensure the completion of the sections in sequence; thus, at any given time there would be 40 sections in progressive stages of assembly. The larger part-sections were machined and prepared for assembly on the actual site, while the smaller ones passed through the machine shops on the conveyor-belt principle. As soon as the first section had been assembled it was fitted with the appropriate machinery, electrical equipment, messing accommodation etc., the same operation on each section being performed by the same workmen for the sake of speed.

The delivery of the completed sections to the U-boat assembly yards at Bremen (Deschimag), Hamburg (Blohm & Voss) and Danzig (Schichau), and the process of final assembly and launching, all had to follow a strict time-table, and it is not surprising that difficulties arose in the early stages of the programme. The section-building yards were at first unable to keep to the schedule, partly owing to delayed delivery from subcontractors of certain important fittings and partly to the first part-sections having been badly rolled and exceeding the specified tolerances, which necessitated additional work. As a consequence, the supposedly complete sections for the first boats arrived at the assembly yards late and in an unfinished state, which in their turn meant additional work in the time allotted for U-boat assembly. The Central Shipbuilding Committee, however, would permit no postponement of U-boat completion dates and ruthlessly insisted on strict observance of the timetable. The first boats to be launched, therefore, had much work outstanding - and a lot that was, perforce, skimped - so that they had later to spend long periods in dockyard hands. Indeed, so many imperfections showed up in the first seven boats that they could be used only for training and experimental purposes.

All these difficulties, together with prevailing differences of opinion, caused tension and antagonism between the Central Shipbuilding Committee, the Naval Command and the dockyard authorities. This unfortunate atmosphere prevailed until the summer of 1944, when there was a noticeable improvement, due in part to the influence of the Shipbuilding Commission, which under Admiral Topp had been created at the beginning of that year, and which thereafter acted as mediator between the Naval Command and the Armaments Ministry on behalf of the Shipbuilding Committee.

462. U-boat building under the administration of the Armaments Minister

There is no need here to go into details of how the great new building programme was implemented, or to discuss the differences which arose between the Naval Command, the Central Shipbuilding Committee and the dockyard authorities; but even if everything had proceeded smoothly and without interruption we would still have been hard put to it to meet the great demands for material and manpower needed in the section and assembly yards and other areas. Only those who had attended the conferences between the Naval Command and the Shipbuilding Committee in 1944 could form any opinion of the difficulties involved in implementing the programme under prevailing conditions. The country was strained to the utmost in coping with the overall demand for armaments while our industrial centres and dockyards were being blasted by bombs, and carefully timed schedules had continually to be retarded because of bomb damage to works and plant and frequent traffic disruption. At almost every conference some calamity was reported, for instance, the flight of dockyard workmen from the bombed cities, particularly Hamburg, the withdrawal of workmen from the Schichau yard, Danzig, for defence in the East and the destruction of pontoons and cranes used for the transport of U-boat sections. Supply arrangements had continually to be altered and work transferred to other factories in an effort to achieve continuity in production, and it was now manifest that the Commander-in-Chief Navy had been right in May 1943 when he turned over responsibility for shipbuilding to the Armaments Minister. None but the Minister himself could have risked taking on such a vast building programme and only he, with the entire German armaments industry at his command, was in a position to provide alternative production capacity after bombing attacks.

The following figures illustrate the tremendous scale of naval construction achieved from 1943 onwards. Despite great difficulties caused by Allied bombing and an increase in the production of surface craft, 234 U-boats totalling 220,000 tons came from the builders in 1944, against 238 in 1942 when German industry was unaffected by bombing. The highest ever monthly production of U-boats was achieved in December 1944, with 31 - including 22 Type XXI - totalling 38,100 tons; as compared with 24 totalling 20,881 tons in October 1941, 23 totalling 18,929 tons in November 1942, and 28 totalling 22,000 tons in December 1943. The average monthly rate of production in the first quarter of 1945 was still as high as 28,632 tons. These figures, coupled with the fact that completion time was cut down overall by eight to twelve months, show clearly that any disadvantages accruing from the transfer of responsibility for naval construction from the Naval Command to an independent Minister were far outweighed by the advantage of having unrestricted call on the whole armaments industry.

463. Delays in completion and training

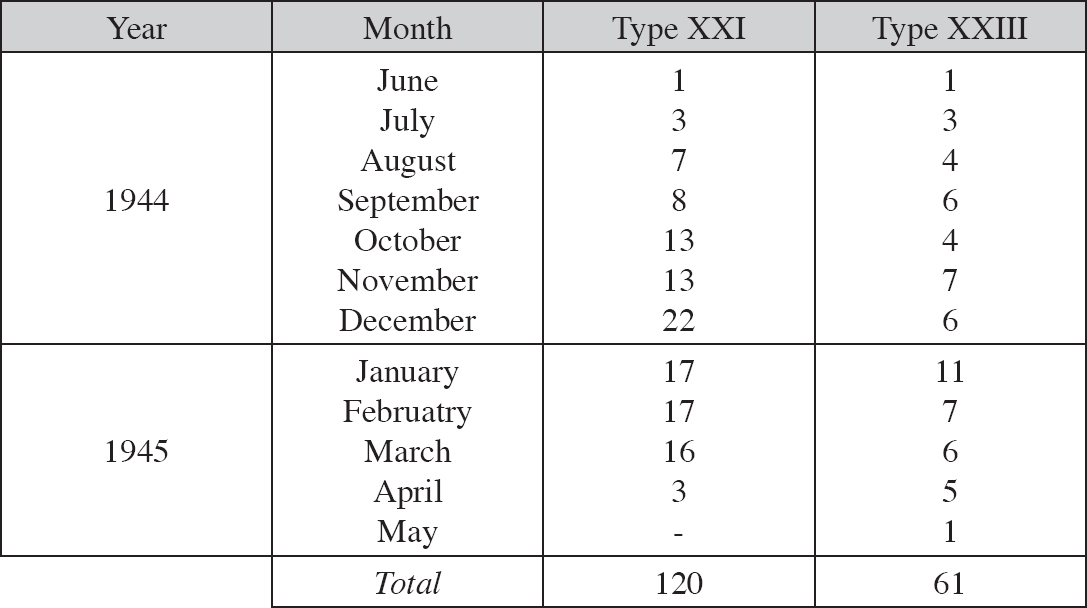

Owing to the circumstances already mentioned, the whole U-boat building programme gradually dropped about five months behind schedule and, although the first Type XXI boat was launched as planned in April 1944, she was not commissioned until June. By the end of October, 32 Type XXI and 18 Type XXIII had been commissioned, while those under construction in the assembly yards were so far advanced that, even allowing for considerable destruction through bombing, a monthly delivery rate of 15 to 20 Type XXI and six to ten Type XXIII could be expected in the immediate future. German records do not show the exact number of new-type boats completed; but from the record of those commissioned, shown in the table below, it can be seen that the expected rate was generally achieved.

As was mentioned in Section 461, the unorthodox methods used in the construction of these boats was responsible for an inordinate number of defects in the first to commission, and frequent interruptions for repair and modification combined to lengthen the crew training period from the usual three months to nearly six. However, by dint of close co-operation between the Construction Office at Blankenburg, the U-boat Acceptance Staff and the Admiral in Charge of U-boat Training, the fundamental defects were eliminated within a few months and, from the autumn onwards, the necessary modifications were incorporated into all U-boats delivered from the builders.

A nucleus of experienced U-boat commanders and petty officers formed the backbone of the new crews, who buckled down to their training with great enthusiasm. Meanwhile, the U-boat Command, which had previously studied the question of tactical employment of the new-type boats, had passed on their findings to the training, experimental and trials staffs and to the U-boat commanders (392). It was thus possible to put the new theories quickly to the test and to incorporate suggested improvements, which thereby hastened the process of establishing a firm basis for both crew training and operational use of the boats. The final “Battle Instructions for Type XXI and XXIII U-boats” were compiled from the evaluation of extensive sea trials carried out in one boat of each type, commanded by two well-trained officers, Korvettenkapitän Topp and Kapitänleutnant Emmermann.

464. Outstanding fighting qualities of the new boats

During the first Type XXI trials run over the measured mile at Hela, it was at once evident that the designed submerged full speed of 18 knots for one hour 40 minutes would not be realised, the maximum submerged speed attained varying between 16J and \7\ knots for from 60 to 80 minutes. However, at medium speeds of from 8 to 14 knots the disparity between design and performance was not so great, and the cruising motors came up to expectations with a speed of 5 to 5 J knots.

A boat proceeding on cruising motors had to schnorkel for three hours daily to keep her batteries fully charged, and at a submerged cruising speed of five knots she could thus traverse the danger area between the Norwegian coast and the south of Iceland in about five days, raising her schnorkel on only five occasions. The schnorkel head was fitted with a Tunis aerial and coated with sorbo rubber as a protection against radar, so the boats were less vulnerable to location and attack from the air than hitherto. Even if the schnorkel were to be located by radar - which by virtue of its absorbent coating was only possible at short range - a boat would be in no great danger, since a sharp alteration of course coupled with a large increase in speed would quickly take her clear of the area and out of range of the aircraft’s sonobuoys; she could then continue for as long as necessary at the silent running speed of five knots, at which it was possible to cover more than 300 miles, or at two to three knots, a speed which she could maintain for 80 to 100 hours without having to schnorkel. The new boats had, therefore, a much better chance than the old type of reaching the Atlantic unobserved.

The silent submerged cruising speed of 5 to 51 knots was also an excellent attack speed and, in the event that this proved too slow, a convoy attack could always be pressed home by using high speed. This capability and the newly introduced echo-ranging gear and plotting-table, specially designed for use in such attacks, gave the Type XXI a decisive advantage over the old schnorkel boats. Furthermore, the Torpedo Trials Staff had developed a special instrument for so-called “programmed firing” in convoy attacks: as soon as a U-boat had succeeded in getting beneath a convoy, data collected by echo-ranging was converted and automatically set on the Lut torpedoes, which were then fired in spreads of six, at five- and fifteen-second intervals. The torpedoes opened out fanwise until their spread covered the extent of the convoy, when they began running in loops across its mean course, making good a slightly greater or lower speed, and in so doing covered the whole convoy. In theory these torpedoes were certain of hitting every ship of from 60 to 100 metres in length; and the theoretical possibility of 95 to 99 per cent hits in an average convoy was, in fact, achieved on firing trails.

In addition to the Lut, an improved torpedo was now available62 which was capable of homing onto propeller noises and virtually immune to Foxer.

Even if she did not entirely fulfil our expectations, the Type XXI U-boat was an excellent weapon when assessed against the A/S capability prevailing in 1944. She had overcome her worst teething troubles; and it was our intention to use a few of these boats within the next four months to resume the battle both in the Atlantic and in remote areas, later disposing an increasing number to the west of the British Isles. By virtue of its great endurance, the Type XXI could reach any part of the Atlantic and remain there for three to six weeks; it could, in fact, have just made the passage to Cape Town and back without refuelling.

It was decided that any attempt at submerged pack tactics, with the support of air reconnaissance, should be delayed until sufficient boats became available; but communication requirements for cooperation between Type XXI U-boats and aircraft had been dealt with and the procedures exercised. For reconnaissance west of the British Isles, the Luftwaffe intended to provide Do 335 aircraft, which by reason of their high speed of 430 to 470 mph could fly direct across the United Kingdom at night (393). FO U-boats did not believe that sufficient aircraft would be made available for proper support in such operations, despite the Luftwaffe’s assurances; however, he was convinced that good results could be obtained without them, since the Type XXI required only one encounter with a convoy - particularly in a remote area - to fire all its torpedoes, with great prospects of attaining a number of hits.

465. Successful development of the Walter U-boat

Despite the tremendous effort devoted to the production of the Types XXI and XXIII, development of the Walter boat continued in 1943. In addition to two large experimental Type XVIII Atlantic boats - U.796 and U.797 - four small Type XVII were under construction, of which U.792 and U.794 were commissioned in November 1943 and U.793 and U.795 in February 1944. Trials with U.793 and U.795 were speedily and successfully concluded, and in March 1944, U.793 reached a submerged speed of 22 knots with the C-in-C Navy on board, eliciting the comment that “with more courage and confidence at the Naval Command we should have had this a year or two ago”. In June 1944, U.792 covered the measured mile, submerged, at 25 knots, a speed never quite achieved by any other boat; but she was shortly afterwards damaged in a collision and was still under repair when the war ended. Work on the construction of U.794 and U.795 was unfortunately skimped, owing to a shortage of labour in the Germania yard at Kiel, and these two boats suffered from defects to such an extent that they were never used for other than experimental purposes. U.793, on the other hand, was very soon ready for service and was used for sea training of the future Walter boat crews, which had been on course at Hela since March 1944. The author actually went to sea in U.793 during October 1944 and was able to satisfy himself that she really could do 23 knots submerged, besides being remarkably easy to handle at high speed.

It was never intended that the U.792 to U.795 series boats should be used in operations; the operational Walter boat being the Type XVI IB, 24 of which were to have been built at Blohm & Voss, Hamburg. However, this order was unfortunately placed, for Blohm & Voss were already hard put to it to cope with their share of the Type XXI programme; thus the project was sadly neglected and the order cut, first to 12 and later to six boats. Furthermore; as labour was constantly removed for work elsewhere, completion of the first boat - U.1405 - was delayed six months to December 1944 and that of U.1406 and U.1407 to February and March 1945 respectively.

On conclusion of trials with the Type XVII in the spring of 1944, work on the two Type XVIIIs had been discontinued, and on 26th May contracts were placed for 100 large Atlantic Walter boats Type XXVIW, displacing 852 tons, the first two to be ready in March 1945 and the whole series completed by October of that year. These boats were designed for a maximum speed of 25 knots over a period of 10 to 12 hours and a performance on electric motors equal to that of the Type VIIC; and since the Walter propulsion unit had to be housed in a gas-tight compartment aft, the arrangement of the torpedo tubes was unorthodox, with four mounted in the bows and a further three on each side of the boat, pointing astern. The original plan had allowed for 250 Type XXVIW boats to replace the Type XXI in service during the summer of 1945; but an apparent shortage of both lead and rubber - later found to be fallacious - soon resulted in revision of this figure to a maximum of 100. Another factor affecting this reduction in the original total was the difficulty seen in producing sufficient Aurol - hydrogen peroxide fuel - for use in the turbines of the Type XXVIWs, as this fuel was also needed for the Luftwaffe’s V2 weapons and the Navy’s allocation sufficed for only 70 boats at most. The building of new factories for the production of Aurol was out of the question, since the cost would have been prohibitive; but the figure of 100 Type XXVIWs was still allowed to stand, although it became clear in September 1944 that this requirement could never be met (394).

For the rest, plans were prepared for an even more advanced type of U-boat, embodying the high qualities of both the Type XXVIW and the Type XXI and equipped with either a closed-cycle diesel, or a Walter turbine adapted to use oxygen fuel. All these plans advanced to a stage where it could be seen that we were on the road to success, but none reached fruition.

OCTOBER 1944-JANUARY 1945

THE SCHNORKEL PROVES ITS WORTH

466. Disadvantages accruing from the loss of the Biscay bases

In an endeavour to keep the refit periods of the Biscay-based operational U-boats as short as possible, we had, since 1941, accorded priority to French west-coast ports as regards the provision of dockyard personnel, machinery and other equipment, at the expense of the U-boat repair yards at home and in Norway.

As a consequence of this policy, the repair facilities at Bergen and Trondheim had been devised to meet the requirements of only about 30 medium U-boats engaged on operations in Northern Waters and, even with an immediate increase of dockyard personnel, could not cope with more than one-third of the Atlantic boats now bereft of their French bases; the remainder had, therefore, to seek repair in German shipyards. In the event, all the large Atlantic boats were allocated to the 33rd Flotilla at Flensburg, which had been formed in the summer of 1944 and used for the reception and disposal of crews recalled from sea to man the new-type boats, and were then, together with the remaining Type VIIs, distributed amongst the Baltic and North Sea yards. This sudden rush of additional repair work imposed a heavy burden on these German dockyards, which were already functioning under difficult conditions, and although the repair of training boats was deferred and additional labour drafted in - mostly from the U-boat building yards - operational boats had still to wait a long time before being taken in hand for protracted periods. Their time spent non-operational was further, and indeed considerably, extended by the necessity of making the passage between Norway and Germany in company with routine supply convoys; the trip from Kristiansand to Kiel often taking from six to eight days, owing to fouling of the route by mines and casualties amongst the escort vessels.

For these reasons the operational boats were inactive for more than twice the time it had previously taken to refit them in western France; and the loss of the Biscay bases thus resulted not only in lengthening the passage to the operational area by 600 to 1,000 miles but also in a considerable reduction in the number of serviceable U-boats. On top of all this, the enemy sought to frustrate our operations from Norway by heavy air attacks on the yards at Bergen, Kiel and Hamburg, by increased minelaying in the Sound and Belts and by air attacks on our convoys. In one air attack on Bergen, on 4th October, two operational boats - U.228 and U.993 - and the crane installation were destroyed, while U.92 and U.437 were so severely damaged that they had to be paid off. Another attack, on 29th of the same month, completely destroyed all those dockyard installations not protected by bunkers and reduced the yard’s repair capacity to about six boats; the bunkers themselves were also hit by bombs ranging from 1,100 to 2,200 lb, but the boats and equipment within escaped damage. On 28th December 1944 the harbour at Horten, where the U-boat crews received their initial schnorkel training, was attacked by 200 aircraft; and although six of the eight boats there managed to clear the harbour in time, of the remaining two, U.73S was sunk and U.682 sustained heavy damage.

Besides these RAF raids, attacks were also made by carrier-borne aircraft against our convoys off the coast and in the Inner Leads, the torpedo-transport U-boat U.1060 being destroyed in one such attack on 27th October 1944. Other U-boats were damaged in the course of these attacks, and those in transit between Norway and Germany, had subsequently to proceed on schnorkel when outside the Leads, which caused further extension of passage times.

SO U-boats West, Kapitan zur See Rosing, who became responsible for the allocation of repair berths and the control of U-boat convoys on 12th October 1944, took immediate steps to increase the capacity of the bases and dockyards in Norway. He also set about devising measures to simplify the U-boats’ task in making rendezvous with their escorts on return from the Atlantic, which was an urgent matter, for there was such a concentration of enemy aircraft off the Norwegian coast that the U-boats could not take the risk of surfacing to fix their position; moreover, it was very difficult to identify the rugged coastline quickly through a periscope, and any prolonged search along the coast for a recognised landmark courted danger from our own protective minefields. Work was therefore put in hand to install new and more powerful radio beacons at prominent positions on the coast.

467. Further operations in the Channel

The selection of attack areas for the Norway-based boats presented somewhat of a problem from October 1944- onwards. Only limited enemy movement had been observed in the North Channel during September and, judging by the weight of A/S countermeasures encountered, returning commanders doubted if many convoys still traversed that area. Our radio intelligence gave similar indications. Since 15th September 1944, radio messages from the FOIC Liverpool to Atlantic convoys had also been transmitted by Land’s End radio station. Furthermore, on 20th September an undecrypted message from the C-in-C Plymouth to convoy HX 307 was seen to be addressed, for information, to the naval authorities at Newhaven and Dover, while on 11th October the destinations of four ships from HX 310 were amended to Southampton and Southend. A September plot of D/F bearings of British forces at sea showed only a few centred off the North Channel and a broad concentration to the south-west of Ireland and in the Bristol Channel, with the old great-circle route between the North Channel and Newfoundland, which had formerly been so well defined, no longer apparent. Finally, convoys had been reported as sighted by three different U-boats, on 13th and 16th September and 4th October, 400 to 700 miles west-south-west of Land’s End. There was, therefore, every indication that the enemy had virtually abandoned the North Channel and was now routing his convoys south of Ireland; certainly, he would only profit from his strenuous efforts to reopen the captured Channel ports if traffic from America were sent direct to France, and it was apparent that the Channel would see the bulk of this in the future.

By the middle of September we were still of the opinion that it would be a mistake to send U-boats from Norway to operate in the Channel; but favourable reports from the last five commanders to return from that area, together with an impression, gained from a study of all the U-boat logs, that the crews had now mastered the schnorkel, caused us to change our minds. We therefore determined to make another assault on the Channel, allowing considerable freedom of action to individual commanding officers. However, their final approach to this difficult area was to be sanctioned only after receipt of a report from each boat, transmitted from a position west of Ireland, confirming that the health of the crew and the state of machinery warranted entry into the Channel for a period of two to three weeks.

468. Operations in the Channel and British coastal waters

There were 36 U-boats at sea on 1st October 1944, with 28 homeward-bound and two outward-bound, and only six in the operational areas - four south of Nova Scotia, one off the North Channel and one north of the Minch - of which four would be returning in mid-month. It was three years since so few boats had operated and, as it was essential to restore pressure in the Atlantic as quickly as possible, six schnorkel boats from group Mitte, at readiness in Norway, were ordered to prepare at once for the Atlantic.

“… By withdrawing six schnorkel boats for the Atlantic we are taking a risk, for in the event of an attack on Norway or Jutland it will not be possible quickly to replace them. However, as it is now late in the year for a large-scale landing, the risk must be taken in the interest of the Atlantic campaign…” (395).

Of the first three boats destined for the Channel, U.1006 was presumably lost before reaching the Atlantic and U.246 had to return because of severe depth-charge damage received in an encounter with destroyers to the south-west of Ireland. The Commanding Officer of U.978, however, got through unmolested and decided to enter the Channel, operating there for three weeks and reporting that he had sunk three ships63 in conditions which favoured continuance of such operations. Accordingly, without waiting for reports from the next two boats - U.991 and U.1200 - -we despatched others to the Cherbourg area, and in the latter half of December there were three or four boats there. That they were meeting with success was clear from numerous intercepted enemy signals; and this trend was confirmed by reports from our local people in Guernsey, who, besides hearing frequent heavy detonations and seeing the glow of burning ships by night, found the wreckage of ships and their boats on the foreshore. As enemy A/S vessels were often observed carrying out sweeps in the near vicinity, the Commandant of the Channel Islands Sea Defences was given permission to engage them with radar-controlled gunfire, irrespective of the presence of U-boats.

On 6th January 1945 excellent results were reported by U.486, which claimed to have sunk one steamship, three escort vessels and a corvette, and to have damaged a liner.64 Three other boats which spent some time in the Channel - U.680, U.485 and U.325 - failed to get to grips with the enemy; and further confirmed successes of four ships aggregating 21,053 tons sunk and one of 7,176 tons damaged can only be attributed to U.772, which was subsequently sunk by aircraft. A third boat was lost by the end of January, when U.1209 ran aground on the Wolf Rock.

Operations were also extended into the Irish Sea, following the same pattern as that laid down for the Channel; and when the first boat to arrive in the area - U.1202 - reported that she had sunk three ships65 we sent a further six boats there in December and by January had achieved quite a heavy concentration. The subsequent loss of six more ships totalling 27,820 tons and damage to another of 2,198 tons, although accompanied by the sinking of three U-boats, caused the enemy to reroute his independent vessels up and down the centre of the Irish Sea instead of along the British coast; but this new route was decrypted on 12th January and passed to the boats, which were thereby able to sink two or three more ships.

In other areas - the North Channel, the north coast of Scotland and Reykjavik - which were patrolled by one or two boats, little was achieved.

469. U-boats demanded for extraneous tasks

Ever since the beginning of the invasion, increasing pressure on German-occupied territory had led to a spate of demands for the use of U-boats on transport and other extraneous tasks. To quote only a few examples: Naval Group West required provisions for the 80,000 men manning the coastal fortresses; ammunition was urgently needed at Dunkirk; and Army Group North was short of both ammunition and M/T fuel.

Each such demand received careful consideration, but almost all had to be rejected. Even the Type XIV supply U-boats, which carried 100 to 200 tons of cargo, would have been quite unable to satisfy the combined requirements of Group West and of Army Group North; but, as it was, only operational-type boats were available, capable of stowing 30 to 40 tons of cargo when eight of their torpedoes had been removed. Supplying the western fortresses, alone, would have monopolised all Type VIICs, bringing Atlantic operations to a halt for several months. In the case of Dunkirk, the transport of ammunition proved impossible in face of the mine threat and general navigational difficulties, but a single concession was made to the Commandant Sea Defences Loire when U.773 and U.722 were sent to St Nazaire with anti-tank weapons, ammunition and medical stores, returning to Norway in December with cargoes of non-ferrous metals.

A request from Naval Command, Norway, for the despatch of U-boats to seek out the enemy aircraft carriers operating off the Norwegian coast, had also to be turned down. Not even in the “good old days” had we succeeded in locating specific enemy formations by systematic search of the open sea, any such success being purely fortuitous, and now that it was necessary to operate U-boats continuously submerged the prospects for the older boats were nil. However, as incessant carrier-borne attacks on our convoys in Norwegian waters were threatening to paralyse the whole supply system, C-in-C Navy ordered that an attempt be made to attack the carriers as they entered and left Scapa Flow. Accordingly, at the beginning of December, U.297 was stationed south of Hoy and U.1020 south-east of Ronaldshay, with targets restricted to troop transports and above so long as they themselves remained undetected. These two boats were reinforced during the month by schnorkel boats from Northern Waters. U.274 and U.1020 never returned; the former was destroyed by aircraft to the south-west of Hoy, after sinking the frigate Bullen, and the latter was lost through cause unknown. Another boat - U.312 - carried away her rudder on the rocks while attempting, on her own initiative, to enter Hoxa Sound, but managed to escape and eventually reached Trondheim. The watch on Scapa Flow was finally abandoned on 14th January, after four fruitless weeks, when the two boats still on patrol were given freedom to operate southwards along the Scottish coast, which they did without success.

From November 1944, in another effort to waylay the enemy forces operating off the southwest coast of Norway, convoys were frequently escorted by a U-boat, stationed on the seaward quarter and ready to counter-attack. On 11th January 1945 one of these escorting U-boats - U.427 - claimed to have observed a hit by one of two T5 torpedoes fired at an attacking force of three British cruisers or destroyers. This hit was confirmed by hydrophone from another boat, and an aircraft, which was in radar contact with the retiring enemy, later established the presence of only two ships; we thus considered that one vessel had definitely been sunk and announced this in an official report, but British records make no mention of any such loss. At various times in February and March 1945, more than ten U-boats were employed on these escort duties.

470. Successes off Halifax and Gibraltar: Return of the U-boats from the Indian Ocean

From October 1944 onwards an average of two large U-boats patrolled the North American coast from the Gulf of St Lawrence to the Gulf of Maine, where, by the end of December, two ships totalling 12,677 tons had been sunk and another of 7,134 damaged.66 In addition, U. 1228 sank the Canadian corvette Shawinigan and U. 1230 the Canadian minesweeper Clayoquot, while U.1223 damaged the Canadian frigate Magog. During two convoy attacks, on 4th and 14th January 1945, U.1232 sank four ships totalling 24,531 tons and damaged another of 2,373 tons. In a clandestine operation on 30th November 1944, U.1230 landed two agents near Boston without being observed, but according to press reports the agents were arrested a few days later. The German Secret Service was consistently unfortunate in its landing of agents on the coast of the United States; either the coast was too closely watched or the agents themselves were inadequately trained, for it was never long before they were apprehended. However, at this stage of the war it is not inconceivable that agents preferred to give themselves up.

U.1227 arrived off Gibraltar in mid-October 1944 and remained there for four weeks; but, apart from torpedoing the Canadian frigate Cheboque on the outward passage, she failed to get in an attack. Nevertheless, she reported such favourable operational conditions in that area that we sent U.870 to follow her. While outward bound and 400 miles north-west of the Azores, U.870 chanced to be overrun by a convoy on 20th December, from which she torpedoed LST 359 and the US destroyer escort Fogg. She maintained patrol west of Gibraltar for three weeks, and between 3rd and 10th January 1945 attacked several east- and west-bound convoys, from which she sank one ship of 4,634 tons and damaged one of 7,207 tons.

As none of the Indian Ocean boats was equipped with schnorkel, they were all ordered to leave the area by mid-January 1945, at the latest, so as to clear the danger zone, which stretched from the south of Ireland to the Norwegian coast, while the nights were still long. Each carried a cargo of vital raw materials. The first boat to leave - U.168 - which sailed from Jakarta at the beginning of October, was sunk off the Javanese coast by an Allied submarine, and so became the second boat to be lost in this way within a fortnight; and although the remaining commanders were warned to take every precaution when traversing the Allied submarine zones off Penang and Jakarta, the next two boats - U.537 and U.196 - were both lost in the same way.67 Of the rest, U.181 succeeded in reaching the Cape, where she developed bearing trouble, was forced to return to Jakarta and was subsequently turned over to the Japanese, U.510, U.532 and U.861 sailed in mid-January, their fortunes having already been recounted in Section 431, and U.862, whose commander was a former merchant service officer well acquainted with Australian waters, was given permission to visit the west coast of that country before returning to Germany. She put to sea in mid-November 1944, without divulging her intention, and on 24th December sank an American Liberty ship to the south of Sydney. Another ship was sunk 700 miles west of Perth on 6th February, while U.862 was on her return passage; but we never discovered why no other targets were encountered in the busy area south of Sydney.

471. Surprisingly good results in the period October 1944 to January 1945

In the spring of 1944, during the transition to containing operations in the Atlantic, Dönitz was firmly convinced that it would no longer be possible to use the old-type U-boats offensively. Certainly he expected the introduction of schnorkel to ease the situation, and this had been confirmed to his satisfaction during the anti-invasion operations in the Channel; but, as these boats were forced to operate in the face of the strongest opposition from both air and sea without having had time properly to test or practice with the new equipment, he was unable to form a positive opinion as to its true merit. Moreover, it was impossible to assess what percentage of our heavy losses sustained in June and July had been due to schnorkel failure as opposed to mistakes in drill.

From October 1944, however, all outward-bound U-boats were equipped with an improved type of schnorkel and had undergone special training in its use at Horten, or in some other fjord. They were, of course, now working in areas where the degree of enemy opposition varied considerably; nevertheless, to our surprise, a survey of operations up to the end of January 1945 showed, not only that these old-type boats were again capable of achieving results, but that losses had sharply decreased at the same time. Their effectiveness while actually in the operational area and measured in tonnage sunk per boat per day was exactly equal to the figure for August 1942. However, in those early days the operational area had been entered on crossing the line joining Iceland and Scotland. Now it lay right under the enemy coast. As a consequence of this much longer passage at a slow schnorkelling speed, but also owing to a disproportionate time spent in harbour, the boats were not fully utilised. Whereas in August 1942, out of 100 days the average U-boat spent 40 in harbour and 60 at sea, of which 40 were spent in the operational area, in December 1944 she spent 63 in harbour and 37 at sea, only nine of which were in the operational area. The number of effective boats was therefore much smaller, with total sinkings proportionately reduced (396). The most surprising revelation of the whole survey was to be found in the fact that our losses, amounting to 18 boats in four months, at something over 10 per cent of the boats at sea, were little higher than those recorded from the latter half of 1942. Thus it was no longer correct to talk of containing operations; on the contrary, in seeking out the enemy in his own coastal waters the U-boats were, in every respect, operating offensively.

“… It might have been expected that, with large numbers of schnorkel boats working in difficult areas, losses would increase; but this has not been the case. On the contrary, losses are down to the 1942-1943 level, which fact provides fresh and, perhaps, the most striking proof of the inestimable worth of the schnorkel…

“This changed situation in the latter part of 1944 has not only given the crews of old-type boats new faith in their weapons, but has also shown the new-type boats, with their high submerged speed and endurance, to have been rightly conceived and promising of great achievements…” (397).

472. Shallow water as the best protection against location

The remarkable drop in U-boat losses was attributable to two factors: the schnorkel, and the conditions prevailing in coastal waters, where the U-boats were almost exclusively employed.

After several unsuccessful attempts, our constructors had at last devised a satisfactory method of fixing the Wanze and Naxos aerials to the schnorkel head, which at normal height have a radar echo only one-quarter to one-eighth the strength of that from a surfaced U-boat and could thus be located from the air only at short range, when the aircraft’s radar would also be apparent on the search receiver. Moreover, the schnorkel was very difficult to identify in a seaway. Thus, with the aid of her search receiver and periscope (the latter had to be manned while schnorkelling) a U-boat was reasonably certain of observing an attacking aircraft, by day or night, in time to reach depth before bomb release. Even in a smooth sea the trace left by a diving schnorkel provided a poor point of aim and bombing in surprise attacks had generally proved inaccurate.

Since U-boats in the open sea, particularly in rough water, were now less frequently located from the air, the enemy A/S forces had fewer opportunities for attack and relied more on their hydrophones for the long-range detection of schnorkelling U-boats. This constituted a serious danger, since the noise of the U-boat’s diesels effectively drowned that of an approaching vessel. To minimise this danger, schnorkelling was interrupted every 20 minutes for an allround hydrophone search, during which the boats usually went to 20 metres. But despite this added precaution, boats were sometimes taken by surprise and, like U.246, received damage from the first depth-charge attack. The threat was particularly acute if enemy vessels in the U-boat transit areas - between the Shetlands and Faroes, southwest of Ireland and west of the English Channel - lay with engines stopped and could not, therefore, be detected by hydrophone sweep. However, it was undesirable to interrupt schnorkelling more often for listening purposes, since, even with three periods an hour as the standard, only 10 to 12 minutes in every 20 remained available for battery-charging. Any shortening of this time would have entailed schnorkelling for half the night in order to ensure a capacity charge. The new Type XXI boats would be in no danger of a surprise surface attack while schnorkelling, for they were to be equipped with supersonic echo-ranging gear (S-Gerdt) capable of locating other vessels within a radius of 4,000 to 7,000 metres.

During the first Channel operations, boats actually in the area had frequently found insufficient time for schnorkelling, but four months’ experience now showed that no great difficulty was to be expected in recharging when operating in coastal waters where enemy opposition was of normal proportions. Moreover, the enemy shore radar stations could locate a schnorkel only at very short range; at all events, while protected against air- and sea-borne radar by the coastal formation, rocks, buoys, fishing vessels and the like, individual U-boats had schnorkelled offshore undisturbed, with land-based radar audible up to strength 4 to 5. On detection by surface A/S forces, the U-boat certainly stood a better chance of evasion by heading into shallow water rather than into the open sea, as rocks and wrecks both produced false asdic echoes, while tide-rips and density layers deflected the asdic beam and restricted hydrophone performance. Furthermore, if a boat were damaged, she could bottom and effect repairs as soon as her pursuers were out of range.

FO U-boats continually impressed upon his commanders that, when pursued, they should act contrary to enemy expectations. For instance, after attacking a coastal convoy they should make for shallow water rather than deep water, a procedure which had often proved successful in the North Channel and the English Channel and in the Irish Sea. There were also instances when U-boats, after making a night attack with acoustic torpedoes, had raised their schnorkels and eluded their pursuers by retiring at the maximum permitted speed.

Neither in 1939 and 1940 nor during the US coastal battle of 1942 was the excellent protection of the coast, combined with the effects of tidal streams, so manifest as it was now.

473. Difficulty of finding targets

Although poor hydrophone listening conditions afforded considerable protection to the U-boats, they also had their disadvantages. On several occasions U-boats lying bottomed, or proceeding at depths of 30 to 40 metres, had been run over by ships and convoys whose propeller noises remained unheard until right overhead. In these circumstances there was rarely time to carry out an attack, although a few commanders were quick-witted enough to get off a stern shot with a Lut or T5 torpedo, which, to their surprise, sometimes hit the then distant target after a five- to ten-minute run. As a result of this experience, on 14th December 1944 U-boats operating in coastal waters were ordered to remain at periscope depth during the day, and to refrain from going deeper unless they found a water layer in which hydrophone range was likely to exceed optical visibility.

In these coastal waters targets could not generally be sighted by periscope, or located by hydrophone, at more than 6,000 to 8,000 metres, which was a short range for normal reconnaissance purposes, but regarded as long by boats operating in such areas as the North Channel, the Minch and the Bristol and St George’s Channels. Furthermore, it occasionally happened that, when two U-boats were patrolling the same area, one would be able to make several attacks, while the other, not being exactly on the traffic route, met no targets at all. It was therefore more than ever necessary that the Command should produce a precise and detailed evaluation of all radio intelligence, together with information concerning the enemy’s coastal routes and the times at which traffic passed given points, and that the boats should be kept constantly in the picture. If, despite receipt of this information, a boat still found no traffic:

“… the commander was at liberty to carry out his search for targets beyond the limits of his allotted area and into bays and inlets, without informing the Command…” (398).

There was another reason why U-boats should be free to leave their prescribed attack areas in search of traffic. The enemy, aware that the old-type boats were unable to use their Fat and Lut torpedoes in the dark, so timed most of his convoys that they traversed the more dangerous areas - prominent headlands and areas in which the depth of water ranged between 60 and 120 metres - at night, thereby repeatedly outmanoeuvring the U-boats and saving many of his ships from destruction. Thus, if a U-boat found that propeller noises were audible in her patrol area only at night, she had, perforce, to proceed along the coast until she reached that part of the route traversed in daylight.

474. Intelligence difficulties caused by reduced radio traffic

The restriction of U-boat operations to coastal waters caused the enemy to cut down on his air and surface A/S forces in the Atlantic and to concentrate them in Home Waters. U-boats on passage, while west of 15 degrees West, could, therefore, have surfaced to recharge their batteries at night, or could even have made this part of the passage on the surface. But although commanders made every endeavour to hasten their transit time, they seldom availed themselves of this possibility, the reason for which is well illustrated by the following extract from the log of U.480.

“… 12th September 1944. 0511. 300 miles west of Ireland. Surfaced for the first time in 40 days. The boat stinks. Everything is covered with phosphorescent particles. One’s footmarks on the bridge show up fluorescently. One’s hands leave a luminous trace on the weather cloth. Schnorkel fittings and flooding slots also glow brightly in the darkness. Because of a high stern sea the bridge is constantly awash and the men cannot stand up on the slippery wooden deck; it is therefore impossible either to change or to dismantle the AA guns. The shields of the twin AA guns cannot be opened; the hinges appear to have rusted up and cannot be attended to in the dark. The 3 -7-cm gun is out of action; so shall first transmit my situation report and then proceed on schnorkel until the state of the sea permits me either to change the AA guns, or dismantle them for overhaul below. In view of the strong phosphorescence, however, I shall first surface at daylight to ascertain the outboard state of the boat…”

“… 2nd October 1944.1710. Off the west coast of Norway. Surfaced. The whole flak armament is unserviceable. The gun shields have been torn away from their mountings and are fouling the guns. Everything, including the 3-7-cm gun, is corroded and covered with growth…”

“… 1720. Dived. I do not want to remain on the surface in this state, unless I am compelled to…”

In such conditions commanders preferred to remain submerged, and to surface only to rectify some serious outboard defect - such as a sticky schnorkel valve - or to transmit the required W/T reports on entering the Atlantic and leaving patrol.

At this stage of the war the transmission of a radio message was an event in itself. The loss of France and Belgium, Allied bombing and other causes had deprived us of a number of good radio receiving stations and, moreover, the boats’ radio operators were less efficient and experienced than previously; consequently, messages often failed to reach the home receiving stations, or were received incomplete. The U-boat commanders were generally averse - and rightly so - to using their radio and were apt to give up after one or two abortive attempts to pass a message; in fact, the more cautious of them made no attempt at all. The result was that nearly 50 per cent of the boats maintained radio silence during the whole of their patrol, except to report their arrival at the escort rendezvous position the day before entering a Norwegian base. Indeed, many commanders failed even to do this and merely waited off the coast until they could join up with the escort detailed for another boat.

In former times, if nothing was heard from a U-boat for a fortnight, at most, we could consider her to have been lost; now, however, it took seven to nine weeks - the average duration of a patrol - to establish this fact. Furthermore, since we had now to rely mainly on verbal reports from the commanders, the assessment of the current situation in an operational area was even more difficult than it had been in the Channel during the invasion. There was thus a danger that we should be unable to detect a sudden deterioration in time to take the necessary counteraction.

FEBRUARY-MAY 1945

THE FINAL PHASE

475. The war situation calls for the intensification of the U-boat campaign

The period from autumn 1944 to the end of January 1945 saw a marked deterioration in the over-all war situation. In December our Ardennes offensive had proved a failure; while the great

Russian offensive, which opened on 12th January, achieved a decisive breakthrough at Baranow and brought about a complete collapse on the Eastern Front. In a swift, almost unopposed advance, the Russian spearheads penetrated deep into the industrial area of Upper Silesia, and as far as Kustrin on the Middle Oder, and Frankfurt. On 28th January they established a bridgehead on the left bank of the Oder at Wriezen, only 30 km from Camp Koralle, the U-boat and Naval Staff Headquarters. No forces were available to defend the headquarters against a possible armoured thrust from this bridgehead; the Naval Staff was therefore dissolved, the U-boat Staff and those members of the Naval Staff considered indispensable to the future conduct of the war moving to Sengwarden, Wilhelmshaven, where they remained until the end of April. Dönitz, with a skeleton staff, stayed on in Berlin, thus severing his connection with the U-boat Command and relinquishing personal control of Atlantic U-boat operations for the first time since the beginning of the war (399).

The gravity of the situation did not affect our plans to continue the U-boat campaign, except in so far as operations had to be intensified for the relief of enemy pressure against our coastal communications. In fact, it was preoccupation with the U-boat offensive in British coastal waters that prevented the Allies from taking more effective action against our shipping on the Norwegian coast, in the Skagerrak and in the North Sea, which was important, for, ever since the end of November 1944, a continuous stream of transports had been plying between Norway, Denmark and Germany, carrying reinforcements for the Western Front (400). Besides these nearly 400,000 tons of service stores, ore and pyrites awaited shipment to the Fatherland, and any dislocation of this traffic would have proved a serious handicap.

The U-boats were also committed to an attack on the Allied supply routes to France and the Scheldt, where every ton of war materials sunk in transit would help to delay the Allied build-up for their offensive in the west, a view echoed in a Supreme Command memorandum to the Naval Staff dated 31st December 1944, which pointed out that American stockpiles in Europe could now be regarded as expended and that, hereafter, they would have to rely solely upon sea supplies, which made the role of the U-boat decisive (401).

476. Allied bombing and minelaying delay completion of the new-type boats

Really effective offensive U-boat action was only possible by use of the new-type boats, which should have been ready for operations in November and December 1944, but they were not completed on time. Dönitz, when reporting to Hitler on 12th October, had, in fact, estimated that the first of the Type XXIII and 40 Type XXI U-boats would be operating in the Atlantic in January and February 1945, respectively (402).

From a variety of reports emerging at the end of 1944, it was clear that the enemy possessed precise information on the fighting qualities of the new boats. Allied political and military leaders and the foreign press all warned of the imminent revival of the U-boat campaign, stating that, since withdrawing from the Atlantic, the German U-boat fleet had been reinforced by new boats carrying novel devices for countering Allied A/S weapons and boasting a submerged speed of 15 knots, which would enable them to pursue and attack a convoy even by day. These statements, which revealed an extensive knowledge of the specifications of the new types, also showed that it was almost impossible to keep such information secret over a long period of time (403). By degrees the British people were being prepared for a resurgence of the U-boat war, and at the same time Allied A/S vessels were warned to be ready for encounters with the new type boats. For instance, our Radio Intelligence Service intercepted a voice message from the SO of an Allied task force announcing special measures to be taken during the winter against an expected intensification of U-boat operations.

The German Naval Staff, indeed, expected that the Allies would be ready with counter-measures when the time came:

“… 3rd December 1944. C-in-C Navy has no qualms as to the outcome of operations by the new-type U-boats, with their much improved underwater fighting qualities. In his opinion the greatest problem arising from a resumption of operations will be for the Homeland and the dockyards, for, as soon as we start to sink his ships, the enemy will bring his whole strength to bear against our U-boat transit routes, building and repair yards and bases. Whereas other industries can be moved to areas less threatened, shipbuilding has to remain on the coast and in the large ports, and allows of no substitution…” (404).

Despite an urgent need to protect the new boats against this anticipated enemy reaction, the building of bunkers for the U-boat section and assembly yards lagged behind requirement; furthermore, the hope that by the beginning of 1945 an expanded fighter-aircraft programme, together with production of the new jet fighters, would provide “a roof over Germany” remained unfulfilled. As a consequence the enemy air offensive, which had continued unabated since the end of 1944, succeeded in delaying U-boat production to a much greater extent that had been foreseen by the Naval Staff. These delays were due less to the actual destruction of U-boats - the raid on Hamburg on 31st December 1944 destroyed only one Type XXI and damaged three - than to a retardation in the rate of construction. The 30 to 50 Type XXIs already in commission were principally affected, often having to wait for several weeks for repairs which, in normal conditions and with spares readily available, would have taken only a few days. Frequent fouling of the Baltic routes and of the exercise areas by mines also served to protract the U-boat training programme, so that by the end of January 1945 it was apparent that only one or two Type XXIs - instead of 40 - would become operational during the following month and that no increase could be expected until April. The first of the Type XXIII boats, however, commenced operations in February, as planned.

477. Expectation of increased enemy opposition and minelaying in British coastal waters

As the Type XXI boats were not yet ready, we had to carry on with the old types, but it was doubtful if the battle would continue on such a favourable note as in the previous months, since the enemy was bound to reinforce his A/S defences around the British Isles in an attempt to drive the U-boats from the coast. Dönitz raised this subject on several occasions when in conference with Hitler (405).

“… 1st March 1945. The confining of U-boat operations exclusively to British home waters is undesirable, since it enables the enemy to concentrate his A/S forces in a small area. But, as the slow submerged speed of the old-type boats (VIIC) precludes their employment in any other region, the extension of operations to areas further afield, which might split the enemy defence forces, will only be possible when the Type XXI U-boats become operational. If we still held the Biscay coast, the Type VIIs could, of course, still operate in remoter areas such as the American coast. We do not think that the enemy has yet devised any fundamentally new methods of locating and attacking a submerged U-boat. Nevertheless, we must be prepared for increasing losses in British waters, where the enemy will apply his whole resources to mastering the U-boat menace. And in time he will meet with increasing success by virtue of the strength of his forces…” (406).

The increased use by the enemy of anti-U-boat mines was a danger of unknown quantity and difficult to assess. The German Naval Staff was acquainted with the positions of the two deep mine barrages, laid earlier, in the Rosengarten (between the Faroes and Orkneys) and across the St George’s Channel, but it was not known whether these fields had been supplemented, or if the mines were still active. However, a first indication of the recent laying of anti-U-boat mines came in an agent’s report, received on 15th November 1944, stating that U.1006 had been sunk by a mine in October, to the south of Ireland. The same agent reported, on 24th November, that new minefields were being laid here and there in the North Channel, in small groups close to the sea bed, as a counter to the new, permanently submerged U-boats. He went on to say that these deep mines were being laid outside the declared mine zones and in mine-free passages as a trap for U-boats pursuing convoys, that over 2,000 mines had been laid by the minelayers Plover and Apollo in September and that similar fields were to be laid to the south of Ireland. This information was allegedly obtained from a member of the ship’s company of one of the minelayers (407), but we placed little credence upon it as it seemed improbable that 2,000 mines had been laid in the North Channel on the first appearance of U-boats in that area, where mines were very likely to break adrift in the prevalent heavy ground swell and thereby endanger British shipping. The reported fate of U.1006 was also doubted since, we estimated, correctly, she had been lost between the Faroes and Orkneys.68 Incidently, none of the intelligence supplied by this agent, who had been in England for over three years, was ever substantiated, so he may possibly also have been working for the enemy, and in this case transmitted an Admiralty-inspired report designed to discourage the U-boats from frequenting coastal waters.

The possibility of an increased use of anti-U-boat mines had, however, been taken into account; indeed, since November 1944 all U-boats proceeding to the Irish Sea had been directed either to transit the St George’s Channel surfaced and close to the Irish Coast or to cross the danger area on a known shipping route and at a maximum depth of 30 metres, above which depth moored mines were unlikely to be found because of the danger to Allied shipping.

478. Climax of operations round the British Isles

In February 1945 a good 50 old-type boats became ready for sea. The provision of fuel for these boats presented a problem, as the navy was then receiving only part of its allocation owing to the widespread destruction of transport and other facilities. This difficulty was, however, overcome by taking oil from the Scheer, the Lutzow and other laid-up units. Thirty-six boats sailed from Norway in February, 38 in March and 40 in April and, with the exception of those destined for the British East Coast, all were sent first to a waiting position to the west of Ireland. Their attack areas were then allocated at the last possible moment, based upon the most up-to-date reports of boats returning from operations, the intention being to occupy as many as possible of those coastal areas in which the boats had some prospect of success.

“… The enemy is thereby compelled to provide escorts everywhere, thus dispersing his forces and weakening him in individual areas. There is little point in sending more boats to these confined waters than is commensurate with the volume of traffic, for any considerable success is likely to evoke strong countermeasures, which would temporarily eliminate not only one but probably several boats simultaneously. The occupation of several areas at a time has a further advantage in that it will provide us with greater details of enemy countermeasures and methods of defence and a better idea of how the enemy situation is developing…” (408).

In February and at the beginning of March, reports from the boats operating in the English Channel were most satisfactory. Traffic between Portsmouth and Cherbourg was still plentiful, although it was becoming increasingly confined to the hours of darkness; good opportunities for attacks were also offered between Land’s End and Start Point, where, in addition to routine coastal convoys, parts of incoming HX convoys passed in daylight, and it was here that the Channel boats had found their targets. The A/S situation also appeared generally favourable, our survey to the end of February showing that enemy action had accounted for the loss of only one U-boat (U.772) out of five operating in the area in December, and one out of three in January. U.650 was presumed to have been sunk before reaching the Channel.

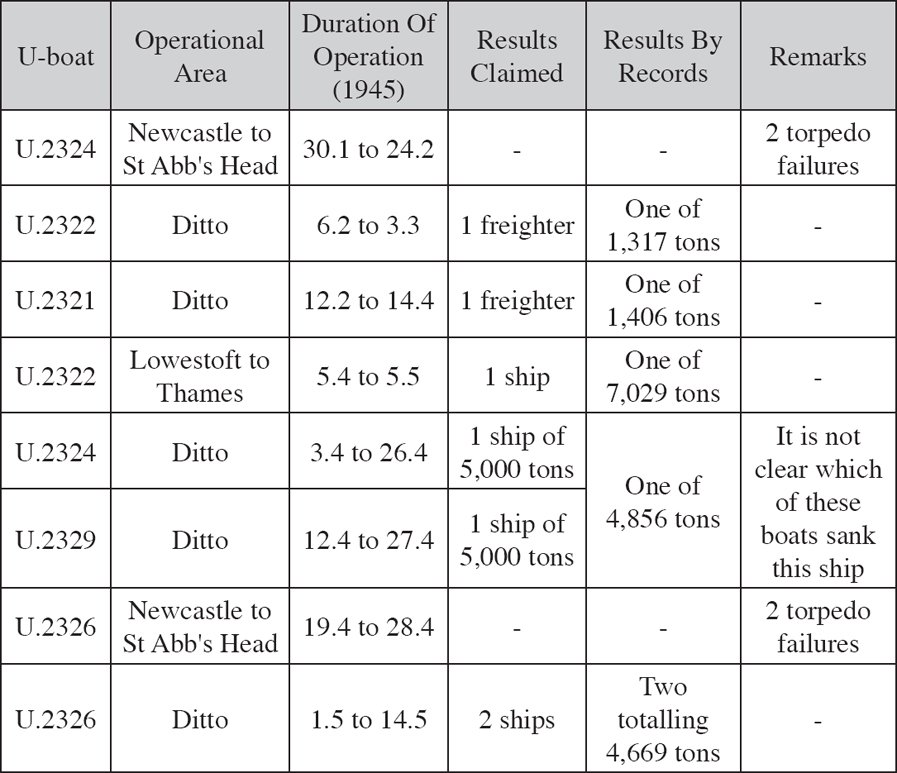

On the strength of this appreciation, we sent nearly a dozen more U-boats to the Channel during the first half of March, disposing them off Cherbourg, south of Portsmouth, north of Ushant and off the south-west coast of Britain, but, as the outward and return passages occupied nearly six weeks, there were never more than five boats in the operational area at any one time. In addition, as a result of favourable reports from commanders returning from the Irish Sea, we followed up in February and March with another seven boats, disposing them north of the Isle of Man, off Liverpool and Holyhead, and in the St George’s and Bristol Channels. Four boats then operating off the North Channel were given freedom to extend their activity to the Irish Sea or the Clyde, while four others were sent to the Scottish coast, between the North Minch and the Pentland Firth, and a further three to the Moray Firth and Firth of Forth.

In February a carefully planned operation - code-named Brutus - was carried out against the Thames-Scheldt traffic by U.245, under the command of Korvettenkapitän Schuman Hindenburg, a highly efficient officer especially selected for the task. Sailing from Kiel, via Heligoland, she proceeded first to the north-west and then south-westward to the Dogger Bank, whence she made due south into the operational area. Her commander was in possession of precise details concerning the convoy time-table, including the times of passing the various buoys marking the route. On 6th February he sank the Henry P. Plant (7,240 tons), some 10 miles east of the North Foreland, and on 15th he torpedoed a small Dutch tanker in the same area. U.245 then returned to Heligoland, which had not been used as a U-boat base for two and a half years.

Most of the large U-boats were sent to the American and Canadian coasts, but U.868 and U.878 were used to transport essential stores and ammunition to St Nazaire, where they turned over some of their fuel to U.255. U.255 had been paid off in August after being severely damaged, but, on the initiative of the SO of the flotilla, she had been repaired meanwhile and manned by base personnel, the SO himself taking command and training the crew. In April she was used to lay mines at Les Sables. U.869 and a Type VIIC boat - U.300 - were sent to the Gibraltar area, the latter at her commander’s request.

Of the Indian Ocean boats, U.862 - the last to operate - returned to Jakarta from Australia on 15th February, while the four on their way back to Germany entered the South Atlantic in February and later sank three independent vessels, a sign that, in face of a diminished threat, the Allies were once more sailing their ships independently.

479. Withdrawal from the British coast

During February and March, only one in four outgoing boats reported their arrival in the Atlantic; in fact, of 114 which sailed in the period February to April only 30 did so, while few of them made a situation report during the return passage. At no other period of the war had we felt our appreciation of the situation to be so unreliable, or an error in that appreciation to be so dangerous for the boats.

Although returning commanders still reported having encountered surprisingly little opposition, the few scraps of information that our greatly reduced Radio Intelligence Service was still able to obtain led us to believe that, from mid-February onwards, the enemy was concentrating his A/S forces in British coastal waters, which the volume of enemy radio traffic evoked by each U-boat contact certainly seemed to confirm, since this traffic appeared to have become greater and to be addressed to a larger number of units than before, particularly in the Plymouth and Lyme Bay areas and in the North Channel.

During March, concern was felt for some of the boats which had been sailed in January and were now approaching the limit of their 70 days at sea, and also for a few others that had sailed later. According to our reckoning they should already have been in their operational areas for two or three weeks, but enemy radio activity had given no indication of their presence so far, and we therefore feared that they might have fallen victim to hunter groups patrolling off the Norwegian coast or between the Orkneys and Shetlands. Our apprehension of mounting danger was further increased by the first confirmation of the laying of new enemy minefields. This came from U.260, which on 13th March, while proceeding submerged at 80 metres and about 20 metres from the bottom approximately 15 miles south of Cape Clear, was severely damaged by a contact or antenna mine. She fortunately managed to surface and make a radio contact and, after getting her engines restarted, landed her crew on the Irish coast.69

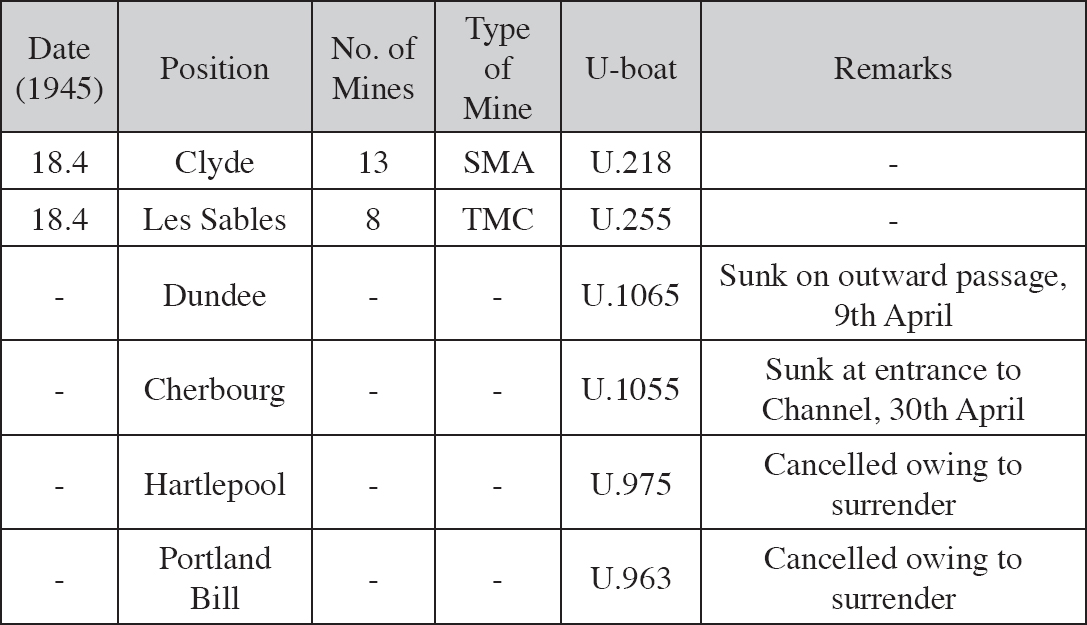

When, at the end of March, it became clear that our losses in the English and North Channels had mounted considerably since the beginning of February, FO U-boats took the only course open to him and withdrew the boats to seaward from the coastal areas, additionally giving them the option of returning to base if the opposition proved too strong. On 30th March and 10th April, in pursuance of this policy, seven boats bound for the English Channel were diverted to new attack areas, 200 and 300 miles west of the Channel entrance, while on 15th April, six more, destined for the North Channel, were given attack areas 30 to 100 miles north of Donegal Bay and three, en route to the Irish Sea, were allowed operational freedom. A number of minelays were also planned, which was always the case when final evacuation of an area was contemplated.

In an attempt to tie down enemy forces in the Atlantic, six boats bound for the American coast were formed into group Seewolf on 14th April, for a westward sweep along the great-circle convoy routes. It was thought that Atlantic convoys were probably less strongly protected at this time and that a surprise success against one of them might induce the enemy to transfer some of his hunter groups from British coastal waters into the open ocean, thereby weakening, to some extent, his A/S concentration in the former area.

480. Losses in the last three months

We heard practically nothing of the course of operations subsequent to March 1945, until the capitulation. However, what information we had showed that U.315 torpedoed three ships south of the Lizard, U.1107 sank two ships of a convoy at the western entrance to the Channel, while U.1022 off Reykjavik and U.245 on a second operation off the Thames had each two ships to their credit. Only two of the planned minelaying operations were carried out, as shown in the following table.

When, after the capitulation, the Allies ordered all boats to report their positions, many failed to respond, and it was only then that the magnitude of our losses in the last months of the war became apparent. There had been a particularly steep rise since the beginning of the year, with seven boats lost in January, 13 in February, 16 in March and 29 in April, this last figure representing about 54 per cent of the boats at sea and being the highest of the whole campaign. In retrospect, and taking into account the location of U-boat sinkings, it is evident that nearly all those boats proceeding to or from various parts of the Channel had tried their luck in the coastal area between the Lizard and Hartland Point - described by their predecessors as favourable - and had fallen victim to the numerous A/S vessels awaiting them there. Whether our losses, generally, resulted from a concentration of the enemy’s A/S forces or from improved underwater location and new A/S weapons, we were no longer able to judge, but the fact that we lost no fewer than 10 out of 16 boats which had sailed for the American and Canadian coasts, an area containing no great number of A/S vessels, seemed to subscribe to the latter possibility. The real situation, as now revealed, was infinitely worse than we had feared and, had the war not terminated on 9th May, we should without doubt have been compelled to withdraw all the remaining old-type boats from the Atlantic. Such severe losses might not have seriously affected the morale of the crews of the new-type boats, but the U-boat arm could not have endured them for another month.

481. The Type XXI U-boats approach operational readiness

From February 1945 onwards, we began to feel the effect of the gradual severance of Northern Germany from the industrial interior. Oil and coal, the most important of all the commodities required by the navy, dockyards and other supporting services, no longer arrived; and stocks remaining in the ports were only just sufficient to satisfy our extensive transport commitments, together with repairs to transports and U-boats. Owing to the Russian threat, U-boat building stopped at the Schichau and Danzig yards in February, and thereafter gradually came to a standstill in the remaining Baltic and North German ports, where work was undertaken only on those Type XXI boats that had already completed their training.