23.

Milk and Cheese Production

In most Amish communities the milk check is an important part of a farmer’s income. But dairying is not a particularly old occupation. Until the 1870s, North Americans drank little milk. Before this time most milk was made into butter and cheese, primarily because adequate refrigeration for the liquid was not widely available. The use of milk increased rapidly after 1900, and many Amish farmers developed dairy herds in response.

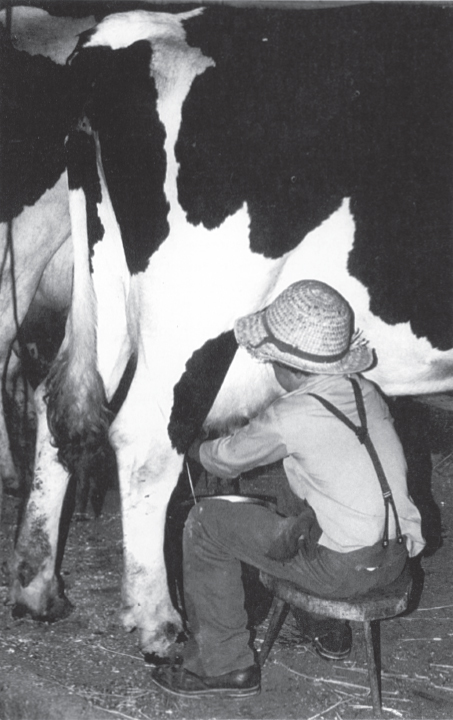

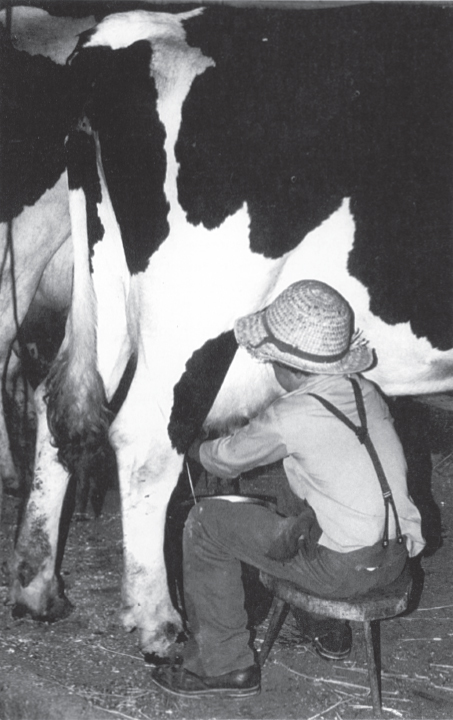

Farmers in many Amish communities do all their milking by hand. In such settlements as Geauga County, Ohio, and Adams County, Indiana, virtually all milking is done in this way. The same holds true for a large percentage of districts in Holmes County, Ohio, and LaGrange County, Indiana.

Where hand milking is still practiced, the whole family usually takes part in the morning and evening ritual. Every family member who is able milks several cows. As the family grows, so does the herd of cows.

Mechanical Milkers

Milking machines were introduced in 1905. Farmers were slow to adopt milkers, however, and in 1950 only 59 percent of all U.S. dairy farms had such machines. (An even lower percentage of farms that had cows but were not primarily dairy operations used milkers at this time.)

More than half of all Old Order Amish dairy farmers milk their cows by hand.

The Amish in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, began using milkers relatively early, in the 1950s. Milking machines later were permitted in Arthur, Illinois; Nappanee, Indiana; and some districts in LaGrange County and Holmes County.

Amish farms that use machines typically suction milk into individual buckets for each milker, rather than send it through pipes to the storage tank, as in most modern dairies.

The most conservative Amish groups still store milk in old-style metal cans. The milk cans are placed in troughs of flowing water for cooling.

Buyers of Grade A milk in most states require that milk be refrigerated at lower temperatures than are possible with water cooling. Thus, the Amish who insist on maintaining the water cooling method are forced to sell their milk to cheese manufacturers as Grade B product. This explains the presence of large cheese plants in many Amish communities.

In some districts in Ohio and Indiana, farmers comply with buyers’ requirements by putting their milk cans in mechanically refrigerated coolers run by diesel engines. Other Amish farmers use milk cooling devices consisting of metal coils placed directly in the milk cans. An Amish shop near Ashland, Ohio, produces a type of this kind of cooler which operates with circulating cold water. In Lancaster County, Nappanee, and Arthur, Amish dairy farmers comply with Grade A regulations and store their milk in mechanically refrigerated bulk storage tanks.

In the most traditional Amish communities, milk is still stored in cans and cooled by flowing water. This milk must be used for making cheese, because Grade A milk standards require lower temperatures than are possible with this method.

Milk companies further demand that milk be periodically agitated. The Lancaster Amish accomplish this by running an electric agitator on current obtained from a battery. The battery, in turn, is charged by a generator powered by the diesel engine which runs the other milk equipment. Similar methods are used in the Nappanee and Arthur areas.

Feed Storage

Silos first made their appearance in America in the 1870s and rapidly increased in popularity after 1900. There is no evidence that the Amish ever objected to this new feed storage system. Most Amish, however, use concrete silos and some wooden-stave structures rather than the newer, airtight steel silos (Harvestore type). These new silos need to be unloaded with sophisticated equipment that usually requires electrical power, although a few Amish dairymen have developed hydraulic systems to accomplish the task.

The Amish prefer narrow silos because a whole layer can be shoveled off at each feeding, thus limiting exposure to the air, which causes spoilage.

Often, Amish farmers buy old concrete silos from farmers who no longer want them. These are disassembled and rebuilt on Amish farms. Since many of these silos were meant for much larger dairy operations than those the Amish normally have, they are sometimes made into two Amish silos.

Most modern dairy farmers have mechanical silo unloaders which convey the ensilage from the bottom of the silo. Amish farmers, by contrast, must climb up into the silo and shovel down the ensilage from the top. The Amish also do without the automatic feeding apparatus present on many modern dairy farms. These mechanisms require electricity.

Cleaning Methods

Mechanized barn-cleaning systems to dispose of manure are absent on most Amish farms. A few such devices were introduced on Lancaster Amish farms in the 1960s but later were officially disapproved. Today, Lancaster County farmers generally use horses to pull metal devices through the manure trenches. The manure either goes directly into a manure spreader or into a tank which is later pumped or mechanically conveyed into a spreader.

Some Amish farmers have litter carriers running on tracks through the barn, into which manure is hand shoveled. In the Midwest, barns are typically constructed in such a way that the manure spreader can be driven through the middle of the building and loaded directly.

In the Arthur area and a few other places, manure is loaded into the spreader with small tractor-like machines called skid loaders, or “Bobcats.” These are equipped with steel wheels that have rubber tread, rather than with pneumatic tires.