Contrary to popular opinion, Reilly was not tortured or subjected to any physical maltreatment by the OGPU. Seventy-seven years later, Boris Gudz, then a twenty-three-year-old OGPU liaison officer attached to Vladimir Styrne, recalled that, ‘no physical methods were used, I can guarantee that’.1 From the very start their approach was clearly one of respect for someone they considered a worthy adversary. Although he made several statements about himself, his background and his activities since he was last in Russia, he would not be drawn on any of the matters the OGPU most wanted to know about. Vladimir Styrne, credited with being one of the OGPU’s best interrogators, duly noted the results of his initial interviews with Reilly:

7 October 1925

I, Deputy Head of KRO OGPU, Styrne, questioned the accused citizen Reilly, Sidney George, born 1874, Clonmel (Ireland), British subject, father, captain in the navy. Permanent residence, London and more recently New York. Captain in the British Army. Wife abroad. Education: university; studied at Heidelberg in the faculty of philosophy; in London, the Royal Institute of Mines, specialising in chemistry. Party: active Conservative. Was tried in November 1918 by the supreme tribunal of the RSFSR, the Lockhart case (in absentia).2

The following is the full, unedited version of the statement which Reilly made to Styrne, taken from his OGPU file:

During the 1914 war, I joined the army as a volunteer in 1916, until 1915 I lived in New York where I was engaged in military supplies, including supplies to the Russian government. After joining the British Army as a volunteer, I was appointed to serve in the Royal Flying Corps (from 1910 I was engaged in aviation and can regard myself as one of the aviation pioneers in Russia; I was one of the founders of ‘Krylia’, the first aviation society in Russia), where I worked until January 1918. In January 1918 I joined a secret political service, where I worked until 1921, after which I set up a private business of a financial nature (loans, stock companies and so on). During my service in the Royal Flying Corps I had no occasion to come to Russia... In March 1918, being on ‘Secret Service’, I was sent to Russia as a member of the British mission as an expert to report on the current situation (I held the rank of lieutenant at the time). I arrived in Petrograd through Murmansk, then proceeded to Vologda, and subsequently came to Moscow, where I stayed until 11 September 1918, spending most of my time on numerous trips between Moscow, Petrograd and Vologda.

From passive intelligence work, I, like other members of the British mission, gradually switched to a more-or-less active fight against Soviet power, which I did for the following reasons:

The signing of the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty on terms very profitable to Germany naturally aroused concerns about joint actions the Soviet powers and the Germans would take against the Allied powers, to which I should add the existence of numerous reports (which ultimately proved to be mendacious) on the movement of German prisoners from Russia back to Germany, and finally, the anger caused by the oppression of the Allied missions by the Soviet power. I believe that the Soviet government at that time pursued the wrong policy towards at least the British mission, for Lockhart, up to the end of June, in his reports to the British government, recommended that it should pursue a soft line towards the Soviet power. At that time, as far as I remember, the Soviet Government was especially concerned about establishing a regular army, and Trotsky many times discussed this issue with Lockhart, stressing the importance of sympathies for this cause on the part of the Allied governments. The situation radically changed after Mirback’s arrival and the continuous concessions of the Soviet power to his demands (the demands of the German government).

Mirbach’s death triggered an immediate repression against us. We had anticipated that the Germans, apart from other claims, would demand the expulsion of all Allied missions, which did actually happen. Right after that, searches were made of the consulates and some mission members were arrested, but soon released. Also, the order was made banning all Allied officers to travel. From this very moment, I started my fight against Soviet power, which manifested itself mostly in military and political intelligence and in identification of the active elements that could be used in the fight against the Soviet government. For this purpose, I went underground and obtained documents from various persons; for some period of time, for example, I was a commissar in charge of transporting spare vehicle parts during the evacuation from Petrograd, which provided me with a good opportunity to travel between Moscow and Petrograd without any restrictions, even in the commissar’s coach. At this time, I resided mostly in Moscow, changing flats nearly every day. The culmination of my work was my talks with Colonel Burzin, whom I met at Lockhart’s. The essence of the matter you would know from the proceedings records. At the time I passed on to the patriarch a considerable amount of money allocated for the needs of the clergy which was in distressful circumstances then. I want to stress that I never discussed with the patriarch or his entourage any counter-revolutionary affairs, and my intentions were unknown to the patriarch and to his inner circle. The money was allocated from the funds I had received; I had in my possession considerable amounts of money, which, in view of my special status (total financial independence and exclusive confidence due to my ties with highly placed persons) were provided me unaccountably. These very funds I spent on my fight against Soviet power.

I believe that the persons that were brought to the Lockhart trial had nothing to do with me, or in some cases, had a very remote relation to me; as for those who were closely associated with me, they fled to the Ukraine after the discovery of the plot. Meanwhile, I had a very vast net of informers, which I also immediately dissolved right after the discovery of the Lockhart case. I financed their flee to the Ukraine.

Reilly then related the story of his escape from Petrograd (reproduced in Chapter Ten), before moving on to recount:

I was then appointed a political officer in the south of Russia and left for Denikin’s headquarters in the Crimea, in the south-east and in Odessa. In Odessa I stayed until the end of March 1919, and by the order of the British High Commissioner in Constantinople, I was dispatched to make a report on the current situation on the Denikin front and the political situation in the south to officials in London and to Britain’s representatives at the Peace Conference in Paris. In the course of the Peace Conference, I was a liaison in charge of Russian affairs with different departments in London and Paris; during that time, I met B.V. Savinkov. Through 1919 and 1920, I had close relations with different representatives of the Russian émigré parties (the SRs in Prague, the Savinkov organisation, commercial and industrial circles and so on). At that time, I was pressing my comprehensive plan through the British Government concerning support of Russian commercial and industrial circles, headed by Yaroshinsky, Bark and others. All this time, I served the secret service, my main responsibility being to make reports on Russian affairs for Britain’s higher echelon.

At the end of 1920, having become a rather close intimate of Savinkov’s, I went to Warsaw, where Savinkov was then organising a foray into Belorussia. I personally took part in the operation and was inside Soviet Russia. Ordered to return, I went back to London. In 1921 I continued to provide active support to Savinkov, took him to London and introduced him to government circles. The same year I took him to Prague, where I introduced him to government contacts. I also arranged his secret flight to Warsaw.

In 1922 my strategy changed. I was disappointed with intervention. I became increasingly inclined to the opinion that the most appropriate way of struggle would be to reach an agreement with the Soviet power such that would throw open the gates of British commerce and business to Russia. At that time I proposed a project for the establishment of an enormous international consortuim for the restoration of Russian currency and industry, this project was accepted by some in government circles. In charge of this project were the Marconi Company or, to be exact, Godfrey Isaacs, the company’s chairman and the brother of the Viceroy of India. This project was discussed with Krasin and eventually dropped, yet nearly all the elements of this project were taken as a base for the proposed international consortium that was established at the time the Genoa conference was held.

In 1923 and 1924 I was primarily preoccupied with my personal affairs. As for my fight against the Soviet power, I was less active here, although I wrote much about it in the papers (British) and supported Savinkov, consulting influential circles in England and America on Russian affairs.

In 1925 I resided in New York. In late September 1925 I illegally crossed the Finnish border and arrived in Leningrad and subsequently

Moscow where I was arrested.

[signed] Sidney Reilly3

Two days after making this statement, on 9 October, Reilly volunteered that:

I arrived in Soviet Russia on my own initiative, hearing from Bunakov of the existence of an apparently important anti-soviet group. I have always been actively engaged in anti-Bolshevik matters and to these I have given much time and my personal funds. I can state that the years 1920–24, for instance, cost me at a very minimum calculation £15,000-£20,000.4

Some weeks later Pepita received a further letter from Boyce in Helsingfors, dated 18 October, in which he broke the news to her that things had definitely gone wrong:

I am on my way to Paris via London and hope to be with you on Thursday or latest Friday. The position I am sorry to say is much worse than I had hoped from the information previously received. It appears that at the last moment just before they hoped to complete the whole business a party of four of them were prospecting in the forests near by and were suddenly attacked by brigands. They put up a fight with the result that two were killed outright. Mutt5 was seriously wounded and the fourth was taken captive.6

Promising to meet her in Paris when he would hopefully have more precise and up-to-date news, Boyce signed off. At this point it is clear that Pepita considered the possibility that Boyce might be an OGPU double agent who had entrapped her husband.7 This would not be the last time that such suspicions were to fall on Boyce.

From the OGPU interrogation records, it would appear that the information Reilly had thus far given about himself was as far as he was willing to go in terms of volunteering the information they were demanding. On 13 October Reilly responded to Styrne’s ultimatum, to co-operate fully or face the consequences, by categorically stating, ‘I am unable to agree’.8 On 17 October he again wrote to Styrne, emphasising that he would not provide the ‘detailed information’ they were seeking.9 Psychological methods were therefore brought to bear on him, which ultimately succeeded in persuading him to co-operate. Even when this point was reached on 30 October, it is clear that Reilly did his best to drag things out.

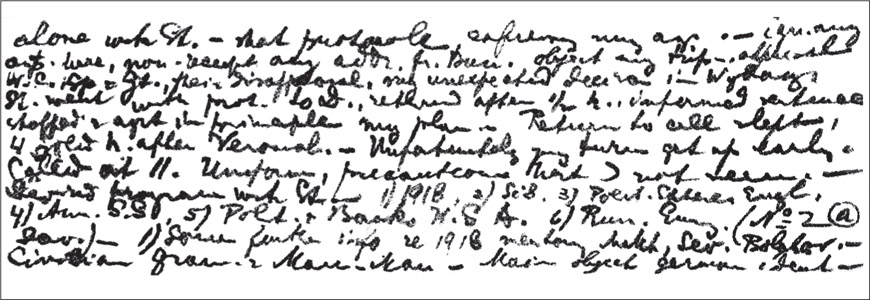

How then was he persuaded to talk and what did he tell them? Reilly himself left a trail of clues in the form of daily notes he made during his last week in cell 73. Using a pencil he made tiny handwritten notes on cigarette papers. These he hid in his clothing, in his bed and in cracks in the plasterwork of the cell walls. They were later found when the cell was searched, and photographic enhancements made by OGPU technicians.10 The handwriting in the daily diary is clearly identifiable as Reilly’s. The constructions, grammar and use of abbreviations are not only in keeping with his general written style, but are consistent with other examples of earlier diaries he kept.

In 1992 Robin Bruce Lockhart called into question the diary’s authenticity in a revised edition of his Ace of Spies book,11 dismissing it as ‘Soviet disinformation’. If it was an OGPU fabrication, however, created solely to mislead the West, why was it never used at any time during the following sixty-six years of Communist rule in the Soviet Union? On the contrary, it remained classified at the highest level and was kept securely in the archives of the OGPU and its successor organisations.

Why he wrote the diary is another question altogether. The most likely scenario is that he assumed, or at best hoped, that he would eventually be released to the British authorities. Had this happened, he would, no doubt, have tried to smuggle the diary out with him. Like the postcard he posted to Ernest Boyce shortly before his arrest, it was a testament or boast to the fact that he had entered the lion’s den and returned to tell the story. It was also a record of OGPU interrogation techniques, which he was sure would be of interest to SIS. The diary itself contains many abbreviations, and the following account reproduces only the text of which the meaning is clear and incontrovertible –

Friday 30 October 192512

Additional interrogation in late afternoon. Change into work clothes. All personal clothes taken away. Managed to conceal a second blanket. When called from sleep was ordered to take coat and cap. Room downstairs near bath. Always had premonition about this iron door. Present in the room are Styrne and his colleague, assistant warder, young fellow from Vladimir gubernia, executioner13 and possibly somebody else. Styrne’s colleague in chair. Informed that GPU Collegium had reconsidered sentence and that unless I agree to co-operate the execution will take place immediately. Said that this does not surprise me, that my decision remains the same and that I am ready to die. Was asked by Styrne whether I wished time for reflection. Answered that this is their affair. They gave me one hour. Taken back to cell by young man and assistant warder. Prayed inwardly for Pita,14 made small package of my personal things, smoked a couple of cigarettes and after fifteen to twenty minutes said I was ready. Executioner who was outside cell was sent to announce decision. Was kept in cell for full hour. Brought back to the same room. Styrne, his colleague and young fellow. In adjoining room executioner and assistant all heavily armed. Announced again my decision and asked to make written declaration in this spirit that I am glad I can show them how an Englishman and a Christian understands his duty.15 Refusal. Asked to have things sent to Pita. Refused. They said that no one will ever know about it after my death. Then began lengthy conversation – persuasion – same as usual. After three-quarters of an hour wrangling, a heated conversation for five minutes. Silence, then Styrne and colleague called the executioner and departed. Immediately handcuffed. Kept waiting about five minutes during which distinct loading of weapons in outer rooms and other preparations. Then led out to car. Inside were the executioner, his warder, young fellow, chauffeur and guard. Short drive to garage. During drive soldier squeezed his filthy hand between handcuffs and my wrist. Rain. Drizzle. Very cold. Endless wait in garage courtyard while executioner went into shed – guards filthy talk and jokes. Chauffeur said something wrong with radiator and pottered about. Finally start, short drive and arrival GPU by north – Styrne and colleague – informed post-ponement twenty hours was communicated. Terrible night. Nightmares.

According to OGPU reports, Reilly spent the night alternately crying and praying before a small picture of Pepita. It seemed that the classic ‘mock execution’ technique had finally shaken his resolve. The scenario he describes, the endless waiting, the uncertainty, followed by a postponement of the execution is typical of this psychological method of interrogation and no doubt induced the nightmares to which he refers.

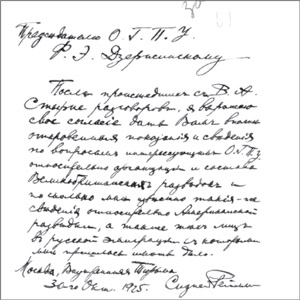

Much controversy surrounds a letter written on the same date as the ‘mock execution’, 30 October. The full text of the letter, which is contained in the OGPU file on Reilly, is as follows:

To the Chairman of the OGPU

F.E. Dzerzhinsky

After the discussions that have taken place with V.A. Styrne, I express my agreement to co-operate in sincerely providing full evidence and information answering the questions of interest to the OGPU relating to the organisation and personnel of the British intelligence service and as far as it is known to me what information I have relating to the American intelligence and likewise about those persons in the Russian émigré organisations with whom I had dealings.

Moscow, the Inner Prison,

30 October 1925

[signed] Sidney Reilly16

Again, there have been suggestions that this too was an ‘OGPU fabrication’. Gordon Brook Shepherd, for example, asserts that:

… it is inconceivable that Reilly, who had throughout displayed defiance, would have failed to mention [in the diary] such a volte-face. It seems all the more probable therefore that the document was produced by the OGPU’s diligent factory of lies and forgery to make things look neat and pretty in their files.17

Edward Gazur, the FBI counter-intelligence officer who debriefed Alexander Orlov after his defection to the US, was even more emphatic: ‘there is no doubt in my mind that Orlov did not know of the existence of such a letter when he died in 1973 as he would have certainly addressed the matter with me’.18 He is firmly of the view that ‘the letter was a fabrication conceived and floated by the KGB [sic]’.19 Gazur takes his argument further by reasoning that ‘had Reilly confessed, he would have likewise been placed on trial if only for the Soviets to reap an extraordinarily bountiful harvest of propaganda’.20

On 30 October 1925, Reilly wrote to Cheka boss Felix Dzerzhinsky, in a last ditch effort to buy himself more time.

This scenario is a most unlikely one, however. There is no evidence that the Bolsheviks ever had any intention of subjecting Reilly to a show trail. Not only had he already been tried in absentia in 1918, and been sentenced to death, they had already announced his death via the Moscow Trust Council meeting within days of his arrest. Clearly, they would have found it a little difficult to then bring him back to life in order to place him on trial. Furthermore, Reilly’s letter can in no way be described as a ‘confession’. It is purely a statement of intention that he is prepared to co-operate. Savinkov, on the other hand, certainly did ‘confess’ in every sense of the word, and the statement he made was a clear recanting of his opposition to the Bolsheviks:

I unconditionally recognise your right to govern Russia. I do not ask your mercy. I ask only to let your revolutionary conscience judge a man who has never sought anything for himself and who has devoted his whole life to the cause of the Russian people..21

Reilly, on the other hand, no doubt hoped that the letter would save his life or at least buy him time. In fact, his own handwritten notes testify to the fact that during the following five days he did exactly what he said he would do in the Dzerzhinsky letter. It is also clear, however, that what he told them was generally low-grade information, much of which they already knew. The one thing they were keen to learn more about, the identity of SIS agents currently working in Russia, he was unable to tell them, as he had had no connection with SIS for over four years.

Saturday 31 October 1925

Next morning called at 11. Spend day in Room 176 with Sergei Ivanovich and Dr Kushner.22 Apparently Styrne much impressed with his report – increased attention. At 8 p.m. drive dressed in GPU uniform. Walk in country at night. – Arrival Moscow apartment. Great spread. Tea. Ibrahim. Then conversation alone with Styrne – that protocole [sic] expressing my agreement. Ignorance of any agents here – object my trip. Appraisal of Winston Churchill and Spears. My unexpected decision in Wyborg. Styrne went with protocol to Dzerzhinsky, returned half an hour later. Informed sentence stopped and agreed in principle my plan. Return to cell slept, four solid hours, after Veronal.23 – Unfortunately my turn get up early. – Called at 11. Uniform, precautions that I not be seen. Devised programme with Styrne – 1) 1918, 2) SIS, 3) Political spheres England, 4) American Secret Service, 5) Politics and banks USA, 6) Russian émigré Source for information regarding 1918 – Main object German identification, scene at American Consulate24 – Cut off supplies untruth25 – Accused of provocation – 2a) Savinkov’s changed attitude, distrust, my conviction proven. My intentions if Savinkov returned. Rest. Ask whether knew Stark,26 Kurtz.27 Story of Operput,28 Yakushev.29 Then began on Number 2 – SIS. Only introduction. – finished 5 p.m. Retired to room 176. Rest, dinner. At 7 p.m. dictated Numbers 4 and 5. Then cell. Veronal did not act.

The last week of Reilly’s life is recorded in the diary he wrote on cigarette papers in cell 73.

Sunday 1 November 1925

During interrogation tremendous stress laid whether Hodgson30 has any agents and whether any inside agents anywhere in Comintern. – Questions regards Dukes,31 Kurtz, Lifland, Peshkov.32 – Questions regarding Litseintsy.33 Told story of Gniloryboff34 and other case attempted escape. Asked whether any agents are in Petrograd. Lots of talk about my wife – offers any money or position – Sergei Ivanovich Kheidulin.35 Feduleev36 and guard with glasses was with me in cell. No work. Drive in afternoon. Corrected American report.

Monday 2 November 1925

Called 10 a.m. SIS continued – general organisational details.37 Repeatedly asked regarding agents here38 Burberry, Norwegian Ebsen,39 Hudson40 in Denmark and others. Explained why agents here impossible – none since Dukes.41 Returned to my mission in 1918. Kemp,42 misunderstanding with Lockhart.43 Conversation with Artur Khristianovich Artuzov.44 Zinoviev’s letter.45 Doctor dissatisfied with my state. Styrne hopes to finish Wednesday – doubt it. Slept very badly this night. Reading till 3 a.m. Getting very weak.

Tuesday 3 November 1925

Hungry all day. Frunze’s funeral.46 Called about 9 in the evening. Styrne’s letter and message through Feduleev. Six questions, the German’s work, our collaboration: what kind of materials we have concerning USSR and Comintern. China. Duke’s agents. My conversation with Feduleev. Short letter to Styrne. Veronal. Slept well.

Wednesday 4 November 1925

Very weak. Called at 11 a.m. – Apology from Styrne – Friendliness. Work to 5 – later dinner. Later drive, walk. Work to 2 a.m. Slept without Veronal. Styrne gave previous protocol to sign. Began about Scotland Yard – Childs,47 Carter48 – Executive work. Basil Thompson.49 Boris Seid.50 Thoughts on Krasin.51 Law regarding foreigners. Paris. Bunakov travelled to Paris. Long conversation about his trip. Protocol – My thoughts about Amtorg52 and Arcos.53 Wise.54 Broker, Urquhart.55 Possibility of agreement/terms – Russian bondholders. Divide and rule.56 My idea concerning an agreement with England Churchill, Baldwin, Birkenhead, Chamberlain, McKenna. Petroleum groups, Balfour, Marconi, financing of debts in USA – English unrest.57 Questions – again Hudson, Zhitkov, Ferson, Abaza.58 Questions about Persia. – Military attach矕S Faymonville,59 China, makes use of young English agent as an envoy in Russia. Very attentive about Berens. Existence of agents in Arcos and mixed companies. Feel at ease about my death. I see great developments ahead.

His sentence about ‘feeling at ease’ in the context of his death, is not easily translated into English and can therefore be interpreted in at least two different ways. It could mean that he was now recon-ciled to his death, or it could mean that as a result of the past five days of co-operation and the absence of any further talk about carry-ing out his sentence, he was no longer so concerned about the threat.

It should also be acknowledged that whatever conclusions one draws from his ‘diary’ and the OGPU’s corresponding records, Reilly undoubtedly acted with courageous stubbornness during the weeks he was incarcerated at the Lubyanka. Whatever else one could say about his actions and motivations during his life, his final weeks were a credit to his personal courage and resolve. The fact that his resolve was gradually eroded by the effective psychological techniques applied by the OGPU should not detract from this.

By 4 November the OGPU had concluded that Reilly had no more to tell. Equally, there was also the risk that the longer matters progressed, the greater the chance that the border shooting story would be exposed as a sham. Some of those involved in the Trust sting were of the view that Reilly should not have been arrested, as by doing so the whole operation risked immediate exposure. However, the decision to arrest Reilly and ultimately carry out his death sentence was almost certainly taken by Stalin himself.

Boris Gudz remembers that ‘stalin insisted that the Politburo’s line was that under no circumstances was he to be released. He had to be shot, and quickly, because otherwise, eventually, rumours would start doing the rounds that we had him under arrest, foreign governments would find out about the whole thing, there would be all kind of diplomatic problems.’ Stalin foresaw all these difficulties and said: We have to put an end to him once and for all – execute him!‘.60 Although the decision to carry out the sentence was an irreversible one made at the highest level, it would seem that the OGPU officers on the ground did, in fact, exercise a degree of discretion in how it was done. Boris Gudz was personally acquainted with the four officers deputed to carry out the order, and believes that:

There was something quite humane about the way they went about it. Reilly was driven out for walks in the open air of Sokolniki Park quite often, so this particular trip was just another one of his regular outings so far as he was concerned. Maybe he suspected something, because there were a lot of people there that day. Anyway, it was done in such a way that the end came suddenly. I know that for a fact – it was very sudden.61

Grigory Feduleev, the OGPU agent who was in charge of the execution party, described in some detail the events which took place on the evening of 5 November 1925:

For the Deputy Head of KRO OGPU Comrade Styrne

REPORT

I write to inform you that in accordance with the instruction received from you, Comrades Dukis, Syroezhkin, myself and Ibrahim drove out of the GPU yard with No. 73 at precisely 8.00 p.m. on 5 November 1925. We set out in the direction of Bogorodsk. We arrived at the spot between 8.30 and 8.45. It was agreed that the driver, when we got to the spot, would repair a fault in the car, which he did. When the car stopped I asked the driver what was the matter. He replied that there was a blockage and it would take 5–10 minutes to put right. I then proposed to No. 73 that we stretch our legs. Once out of the car I walked on the right-hand side and Ibrahim on the left-hand side of No. 73, and Comrade Syroezhkin on the right hand side about ten paces from us. When we had gone thirty to forty paces from the car, Ibrahim, who had dropped back from us, fired a shot at No. 73, who let out a deep breath and fell to the ground without uttering a cry. In view of the fact that his pulse was still beating, Comrade Syroezhkin fired a shot into his chest. After waiting a little longer, ten to fifteen minutes, during which time the pulse finally stopped beating, we carried him to the car and drove straight to the medical unit, where Comrade Kushner and the photographer were already waiting. At the medical unit the four of us – myself, Dukis, Ibrahim and a medical orderly – carried No. 73 into the building indicated by Comrade Kushner. We told the orderly that this person had been hit by a tram, in any case his face could not be seen as the head was in a sack, and put him on the dissecting table. We then proceeded to take photographs. He was photographed down to the waist in a greatcoat,62 then naked down to the waist so that the wounds could be seen, then naked full length. After this he was placed in a sack and taken to the morgue attached to the Medical Unit, where he was put in a coffin and we all went home. The whole operation was completed by 11.00 p.m. on 5 November.

No. 73 was collected from the morgue of the OGPU medical unit by Com. Dukis at 8.30 p.m. on 9 November 1925 and driven to the prepared burial pit in the walking yard of the OGPU inner prison, where he was put in a sack so that the 3 Red Army men burying it could not see his face.63

Authorised agent of 4th section of the KRO OGPU Feduleev.

It is significant that Reilly’s body was put in a sack so as to avoid anyone not involved in the operation from identifying him. Clearly they were still concerned with word getting out that Reilly had not in fact died on 28 September after all. The fact that he had been shot unawares, rather than by firing squad, as would have been the case had the sentence been carried out in 1918, can be seen as dispensation or even as a mark of respect.

This aside, the way of his death should not obscure the ultimate question of why he found himself entrapped in the OGPU’s snare in the first place. Was Reilly’s death ultimately brought about by his own vanity and lack of judgement? Had the king of the confidence men finally met his match, or were more sinister forces at play?

On 12 August 2001 the Sunday Times reported on the imminent publication of a new book by Edward Gazur under the headline, ‘Double Agent may have sent Ace of Spies to his Death’. According to the report, ‘Gazur contends that Orlov told him that Cmdr Ernest Boyce, an MI6 officer and colleague of Reilly’s, played the key role in entrapping the spy. Boyce was a long-term double agent working for the Russians and was motivated solely by hard cash, said Gazur’.

The spy writer Nigel West was also quoted by the Sunday Times as saying, ‘The reason why this hasn’t come out until now is that Orlov, who was not debriefed by British intelligence, never told anybody but Edward Gazur’. It is therefore puzzling to read in Gazur’s book that:

In 1972, while Orlov and I were going over the Reilly affair, I was not concerned with the identity of the British intelligence officer who had been compromised by the KGB [sic] as it was of no particular intelligence significance in the modern sense and consequently I never thought to ask the name of this individual. To the best of my recollection, Orlov never mentioned or volunteered the man’s identity or if he did it is now long forgotten.64

If this is so, on what evidence is the charge against Boyce made? According to Gazur,

… based on additional facts that Orlov provided at the time combined with independent documentation, I was able to deduce the identity of this key player. Insomuch as Orlov never directly furnished this identity, I originally felt it prudent to do likewise; however, on further reflection I realised that SIS was already aware of the man’s identity and so, as this information was historically relevant, there remained no valid reason to stay silent.65

Gazur gives no details of what these ‘additional facts’ are or to the relevance of the ‘independent documentation’, however. In the absence of such hard and fast evidence, the case against Boyce must remain no more than educated guesswork. This is not to say that the OGPU did not have the co-operation of SIS or former SIS operatives in their quest for Reilly. Before the entrapment operation could begin, a great deal of background research on Reilly must have been carried out. This is clear from OGPU documentation held on him. While a large proportion of the information on Reilly’s personal background is erroneous, it seems clear that this could only be because he himself was the indirect source. It would seem a strong possibility that the information was obtained from an SIS or former SIS colleague, based in part on what Reilly had told that individual or individuals. It should also be borne in mind that these sources may not even have been aware that they were assisting the OGPU, as such back-ground information could well have been sought through cover organisations like the Trust and its supposed anti-Bolshevik agents.

Neither is it likely that Reilly himself volunteered this information about his alter-ego ‘Rosenblum’ during his interrogation, for as we have already seen, he maintained to the very end that he was an ‘Englishman and Christian’ by the name of Sidney George Reilly. To have done anything else would have destroyed what little hope he had of being extradited or swapped on the initiative of the British authorities. Where then could this erroneous information about his Rosenblum background have come from? A key clue lies in the following passage from his OGPU file:

His father was Mark Rosenblum, a doctor who worked as a broker and subsequently as a shipping agent. His mother was née Massino of impoverished noble stock. The Rosenblum family resided at house No. 15 on Alexsandrovsky Prospect.66

The view that 15 Alexandrovsky Prospect was Reilly’s childhood home was the theory of one man, George Hill, who had witnessed Reilly breaking down, as a result of what he believed was an ‘emotional crisis’, outside this house in February 1919. The document also contains most of the other old chestnuts Reilly told Hill about his past. Would it therefore be fair to conclude that Hill was knowingly or unknowingly an OGPU source? Notes written by Vladimir Styrne suggest that Hill, who by 1925 was no longer employed by SIS, may have been collaborating with the OGPU.67 During the Second World War, Hill was seconded to the Special Operations Executive, and posted, at Moscow’s request, to the Russian capital to act as a liaison officer to the NKVD. He later came under suspicion following the 1963 defection of Kim Philby,68 although nothing conclusive appears to have come of this.

In addition to claims that Reilly’s death was a result of betrayal, it has to be said that not everyone accepted that he was dead. Pepita never really came to terms with his death and continued to believe that he was being kept a prisoner.69 Neither in fact did his first wife Margaret believe in his death.70 Whilst their sentiments might be put down to wishful thinking, others have also refused to believe he died for very different reasons. Robin Bruce Lockhart,71 Edward Van Der Rhoer72 and Richard Spence73 have all articulated the view that Reilly defected to the Soviets in 1925 and that his death was a ‘put-up job’ to cover his traces. Indeed, Lockhart devoted a whole book to propounding the thesis, although very little of the book actually relates directly to Reilly himself.74

The whole theory of Reilly’s supposed defection rests entirely on one proposition, however – that he did not die at the hands of the OGPU on 5 November 1925. According to the account of Feduleev, Reilly’s corpse was photographed in the sick bay of the OGPU’s headquarters. This book contains one of the photographs taken that evening. Robin Bruce Lockhart declared that this picture is ‘clearly of someone other than Reilly’ and that the ‘whole story suggests a faked death’.75 He later told this author that the OGPU photographs were clearly fakes as they showed a man, ‘who if not a Chinaman had Asiatic blood’.76 However, this is virtually the same description of Reilly that C himself gave in his cable to SIS Vologda on 29 March 1918,77 when he described his appearance as that of a ‘Jewish-Jap type’. Other official descriptions have also referred to his ‘oriental appearance’.78 Since Lockhart’s dismissal of the mortuary photograph’s authenticity, it has been subjected to forensic analysis by Kenneth Linge, a Fellow of the British Institute of Professional Photography and Head of Photography at Essex Police Headquarters. A veteran of over 200 operational ‘scenes of crime’ cases, Linge has been called upon to give expert testimony in criminal cases throughout the country, and has carried out extensive research into facial identification techniques.

Asked by the author to examine the OGPU photograph of Reilly’s corpse, he compared it with other pictures taken of Reilly over a fifteen-year period, and concluded that ‘the likelihood of the same feature layout and feature form being repeated in another person’s face is so remote as to be virtually negligible. I therefore believe that the person shown on the image, the deceased, is the person shown on the other images’.79 The proposition that the body lying in the Lubyanka Sick Bay is someone other than Sidney Reilly can no longer be sustained.

Reilly’s life ended, as indeed it had begun, shrouded in mystery. He may not, in the words of Robin Bruce Lockhart, have been the ‘greatest spy in history’,80 or even, in the conventional sense, a spy at all. He was, however, certainly one of the greatest confidence men of his time. It is a testimony to his skills of deception that his ‘Master Spy’ myth has outlived him by more than eighty years. In the final analysis, the confidence man’s motto – ‘you can’t cheat an honest man’ – came back to haunt him. Reilly’s own inherent dishonesty had allowed the OGPU to set him up and ultimately to cheat him of his life.

To SGR Killed in Russia, by Caryll Houselander –81

Pure Beauty, ever-risen Lord!

In wind and sea I have adored

Thy living splendour and confessed

Thy resurrection manifest.

Not now in sun and hill and wood,

But lifted on this bitter rood

Of man’s sad heart, I worship Thee

Uplifted once again for me.

For now the Jews cast lots again

On thy raiment, mock Thy pain,

And make Thy torments manifold,

Selling Thee again for gold.

I bow to Thee in this new shrine,

This later calvary of thine;

And in the soul of this man slain

I see Thee, deathless, rise again.