Clock

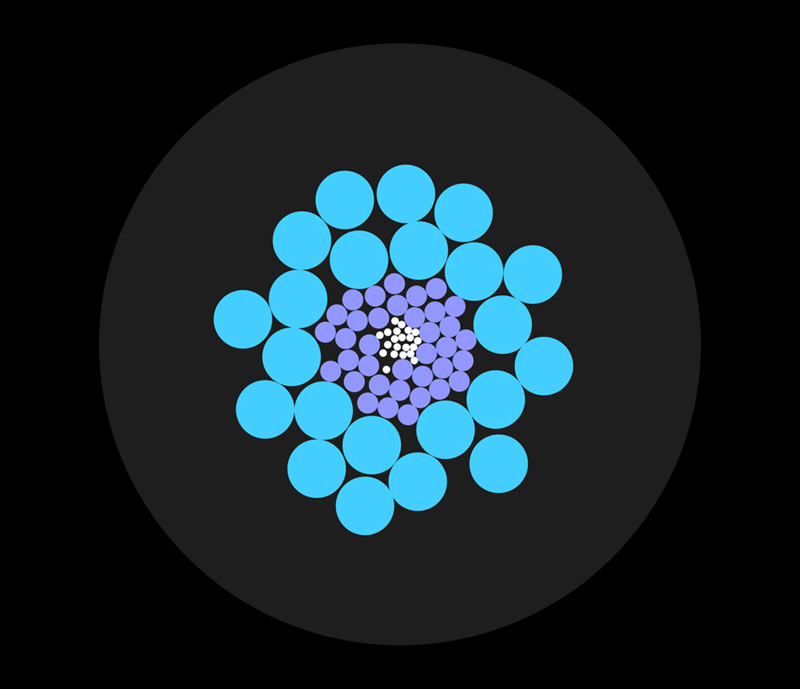

15. Lee Byron's Center Clock (2007) displays the time as countable, bouncy circles. After each minute passes, 60 white “second” circles coalesce to form a new violet “minute” circle, and so on.

Brief

Design a “visual clock” that displays a novel or unconventional representation of the time. Your clock should appear different at all times of the day, and it should repeat its appearance every 24 hours (or other relevant cycle, if desired). Challenge yourself to convey the time without numerals.

You are encouraged to question basic assumptions about how time is mediated and represented. Ponder concepts like biological time (chronobiology), ultradian and infradian rhythms, solar and lunar cycles, celestial time and sidereal time, decimal time, metric time, geological time, historical time, psychological time, and subjective time. Inform your design by reading about the history of timekeeping systems and devices and their transformative effects on society.

Learning Objectives

- Review and research historical methods, devices, and systems for timekeeping

- Devise graphic concepts and technologies for representing time that go beyond conventional methods of visualization and mediation

- Use programming to design, through the control of shape, color, form, and motion

- Apply motion graphics techniques to the representation of temporal information

Variations

- Feel free to experiment with any of the tools at your disposal, including transparency, color, sound, dynamism, and physical actuation. Reactivity to the cursor is optional.

- Avoid using Roman, Arabic, or Chinese numerals, but make the time readable through other means, such as by visualizing numeric bit patterns or using iteration to present countable graphic elements.

- Make a clock that operates at a much slower time scale, changing over months, seasons, or human lifespans.

- Develop your clock for a portable or wearable device, such as a mobile phone, smart watch, fitness tracker, or other standalone computer with a miniature display. Consider incorporating data from your device's other sensors into your design, such as the user's image, movements, body temperature, or heartbeat.

- Free yourself from the desktop or laptop screen, and design your clock for a context of your own choosing. If you could place your clock anywhere, where would it be? On the side of a building? In a piece of furniture? In a pocket? On someone's skin, as a digital tattoo? Include a drawing, rendering, or other mockup showing your clock as you imagine it in situ.

Making It Meaningful

Attempts to mark time stretch back many thousands of years, with some of the earliest timekeeping technologies being gnomons, sundials, water clocks, and lunar calendars. Even today's standard representation of time, with hours and minutes divided into 60 parts, is a legacy inherited from the ancient Sumerians, who used a sexagesimal counting system.

The history of timekeeping is a history driven by economic and militaristic desires for greater precision, accuracy, and synchronization. Every increase in our ability to precisely measure time has had a profound impact on science, agriculture, navigation, communications, and, as always, warcraft.

Despite the widespread adoption of machinic standards, there are many other ways to understand time. Psychological time contracts and expands with attention; biological cycles affect our moods and behavior; ecological time is observed in species and resource dynamics; geological or planetary rhythms can span millennia. In the twentieth century, Einstein's theory of relativity further upended our understanding of time, showing that it does not flow in a constant way, but rather in relation to the position from which it is measured—a possibly surprising return to the significance of the observer.

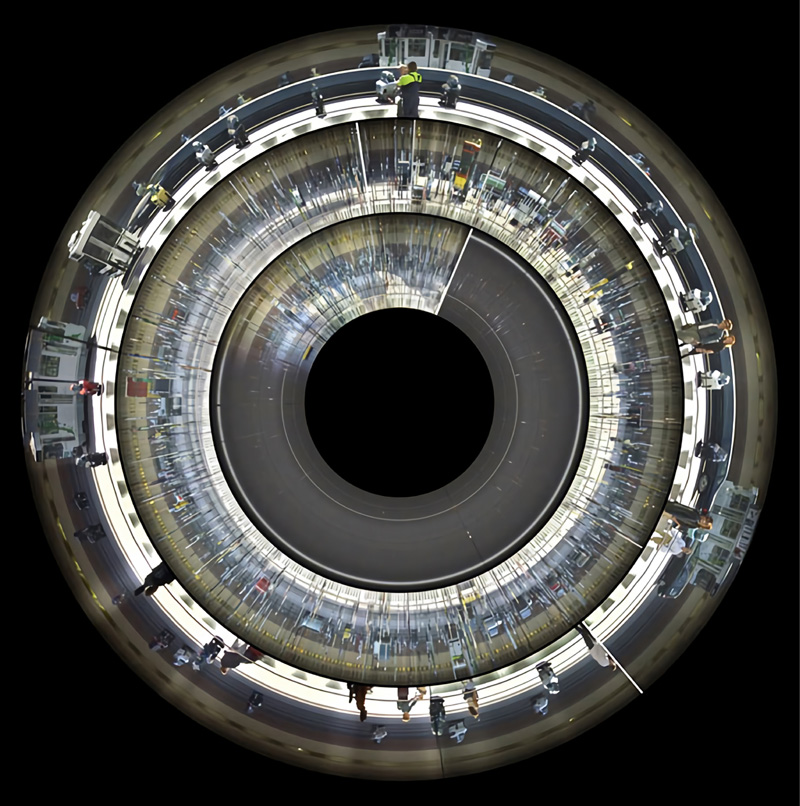

16. Using a slit-scan technique, Jussi Ängeslevä and Ross Cooper's Last Clock (2002) presents activity traces from a live video feed at three different time scales: one minute, one hour, and one day.

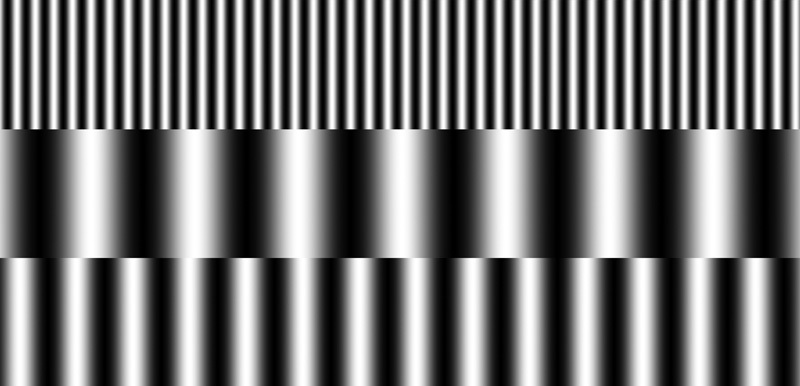

17. In Golan Levin's Banded Clock (1999), the seconds, minutes, and hours of the current time are represented as a series of countable stripes.

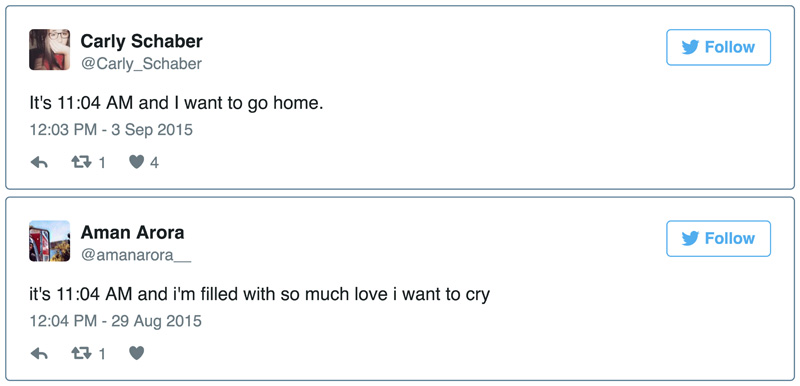

18. Drawing from a gargantuan database of tweets, All the Minutes by Jonathan Puckey and Studio Moniker (2014) is a Twitter bot that reposts mentions of the current time.

19. Mark Formanek's Standard Time (2003) is a 24-hour performance in which 70 workers constantly construct and deconstruct a large wooden “digital” display of the current time.

20. Ink Calendar by Oscar Diaz (2009) uses the capillary action of ink spreading across paper to display the date.

Additional Projects

- Maarten Baas, Real Time: Schiphol Clock, 2016, performance and video, Amsterdam Airport Schiphol.

- Maarten Baas, Sweeper's Clock, 2009, performance and video, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Marco Biegert and Andreas Funk, Qlocktwo Matrix Clock, US Patent D744,862 S, filed May 8, 2009, and issued December 8, 2015.

- Jim Campbell, Untitled (For The Sun), 1999, light sensor, software and LED number display, White Light Inc., San Francisco.

- Bruce Cannon, Ten Things I Can Count On, 1997–1999, counting machines with digital displays.

- Mitchell N. Charity, Dot Clock, 2001, online application.

- Taeyoon Choi and E Roon Kang, Personal Timekeeper, 2015, interactive hardware and software system, Los Angeles Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

- Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen, Artificial Biological Clock, 2008, data-driven mechanical sculpture.

- Skot Croshere, Four Letter Clock, 2011, modified electronic alarm clock.

- Daniel Duarte, Time Machine, 2013, custom analog electronics.

- Ruth Ewan, Back to the Fields, 2016, botanic installation.

- Daniel Craig Giffen, Human Clock, 2001–2014, website.

- Danny Hillis et al., The Clock of the Long Now, 1986, mechanical system, Texas.

- Masaaki Hiromura, Book Clock, 2013, video, MUJI SHIBUYA, Tokyo.

- Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance (Time Clock Piece), 1980–1981, performance.

- Humans since 1982, The Clock Clock, 2010, aluminum and analog electronics.

- Humans since 1982, A Million Times, 2013, aluminum and analog electronics.

- Natalie Jeremijenko, Tega Brain, Jake Richardson, and Blacki Migliozzi, Phenology Clock, 2014, phenology data, software, and hardware system.

- Zelf Koelman, Ferrolic, 2015, software, hardware, and ferrolic fluid.

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Zero Noon, 2013, software system with digital display.

- George Maciunas, 10-Hour Flux Clock, 1969, plastic clock with inserted offset face, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- John Maeda, 12 O’Clocks, 1996, software.

- Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010, film, 24:00, White Cube, London.

- Ali Miharbi, Last Time, 2009, analog wall clock and interactive hardware.

- Mojoptix, Digital Sundial, 2015, 3D-printed form.

- Eric Morzier, Horloge Tactile, 2005, interactive software and screen.

- Sander Mulder, Pong Clock, 2005, inverted LCD screen and software.

- Sander Mulder, Continue Time Clock, 2007, mechanical system.

- Bruno Munari, L’Ora X Clock, 1945, plastic, aluminum, and spring mechanism, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Yugo Nakamura, Industrious Clock, 2001, Flash program and installation.

- Katie Paterson, Time Pieces, 2014, modified analog clocks, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh.

- Random International, A Study Of Time, 2011, aluminum, copper, LEDs, and software, Carpenters Workshop Gallery, London.

- Saqoosha, Sonicode Clock, 2008, 2008, audio waveform generator.

- Yen-Wen Tseng, Hand in Hand, 2010, modified analog electronic clock.

- Laurence Willmott, It's About Time, 2007, language data, software, and hardware.

- Agustina Woodgate, National Times, 2016, modified electric clock system.

Readings

- Donna Carroll, “It's About Time: A Brief History of the Calendar and Time Keeping” (lecture, University Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands, February 23, 2016).

- Johanna Drucker, “Timekeeping,” in Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

- John Durham Peters, “The Times and the Seasons: Sky Media II (Kairos),” in The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- Joshua Foer, “A Minor History of Time without Clocks,” Cabinet Magazine, Spring 2008.

- Amelia Groom, Time (Documents of Contemporary Art) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

- Golan Levin, “Clocks in New Media,” GitHub, 2016.

- Richard Lewis, “How Different Cultures Understand Time,” Business Insider, June 1, 2014.

- Leo Padron, “A History of Timekeeping in Six Minutes,” August 29, 2011, video, 6:37.