Virtual Creature

26. Brent Watanabe's San Andreas Streaming Deer Cam (2015–2016) is a live video stream from a computer running a modified version of Grand Theft Auto V. The artist's mod creates an autonomous deer and follows it as it wanders through a fictional city, interacting with its surroundings and the game's AI characters. During one of its streaming episodes, the deer wandered along a moonlit beach, caused a traffic jam on a major freeway, got caught in a gangland gun battle, and was chased by the police.

Brief

Your job, Dr. Frankenstein, is to create new life. Program a species of virtual organism: it could be a sensate creature, a dynamic flock or swarm, an artificial cell-culture, a novel plant, or an ecosystem. Your software should algorithmically generate the form and behavior of your new lifeform(s). Will they be able to sleep, reproduce, die, or eat one another? Consider the relationships between the individuals in your species and develop a corresponding interplay of simulated forces such as attraction or avoidance. Your creature may benefit from inhabiting an ecosystem or environment with abiotic elements that present additional constraints or opportunities.

Give consideration to the potential for your creature to operate as a cultural artifact. Can it attain special relevance through metaphor or commentary or by addressing a real human need or interest?

Learning Objectives

- Review, discuss, and write functions to animate different types of organic motion

- Design and implement programs using an object-oriented programming approach

- Program an interaction between objects

Variations

- Create an ecosystem containing a pair or “dyad” of creatures that respond to each other in some way: predator/prey, symbionts, etc.

- Program your creature so that its appearance arises from its behaviors, or vice versa. For example, consider how an amoeba's pseudopod is both the visual boundary of its body and also the expression of a tropism. Perhaps the form of your creature's body emerges from an underlying particle simulation, ragdoll physics, or reinforcement learning system.

- Write object-oriented code to encapsulate your species of creature. Exchange your code with other students whose creatures implement the same protocols (eat, sleep, forage, etc.). Collect at least two other species and combine them in an ecosystem. This variation can be executed using a versioning tool such as GitHub, spurring insights into collaborative software development and the importance of code comments.

- Present your digital ecosystem as an augmented projection, siting it on a specific surface. Can your (virtual) lifeforms respond to the physical characteristics of your (real) chosen location?

Making It Meaningful

As the myths of Pygmalion, Golem, and Frankenstein show, the god-like desire to create artificial life (AL) persists throughout our folklore. This impulse also underlies the history of robotics, where gestures are mechanically automated in the Karikuri of Japan and in the early automata of Europe, like Turriano's ”Praying Monk” (c. 1560) or de Vaucanson's “Defecating Duck” (1738). With computers, software simulations of life systems allow behaviors and interactions to be programmed and scaled across massive multiagent systems. Many of these systems exhibit emergence, where self-regulation, apparent intelligence, and coordinated behaviors arise from simple rules followed by many actors.

Whether the medium is hardware or software, the goal of AL is to create the impression that an engineered system is alive. Unlike the creative work of ”character design,” where the focus is on visual appearance, this assignment is concerned with the construction of a creature with responsive, dynamic behaviors that are contingent on environmental interactions. To emphasize this, an instructor may challenge students to instill lifelike behavior in creatures whose bodies are restricted to ultra-minimal forms, such as a pair of rectangles.

A creature without a context is boring—with nothing to do, and no one to do it to. Stories happen, character is perceived, meanings are made when an agent operates on or within an environment that likewise acts on it. By placing a creature into feedback with external forces or subjects, and especially with the actions of an interacting user, we can create companions that stave off loneliness or appear to have feelings, virtual pets like the Tamagotchi that evoke empathy through their fragility, or sublime simulated ecosystems that evolve in surprising ways.

27. Connected Worlds (2015) by Design IO (Theo Watson and Emily Gobeille) is a large-scale interactive installation developed for New York's Great Hall of Science. The work presents six immersive habitats, projected across both walls and floors, that allow visitors to interact with simulated water flows and learn about the role of the water cycle in different ecosystems. Watson and Gobeille devised dozens of responsive creature species to populate the space.

28. Neurophysiologist William Grey Walter's “tortoises” of 1948–1949 were early electronic robots capable of phototaxis and object avoidance.

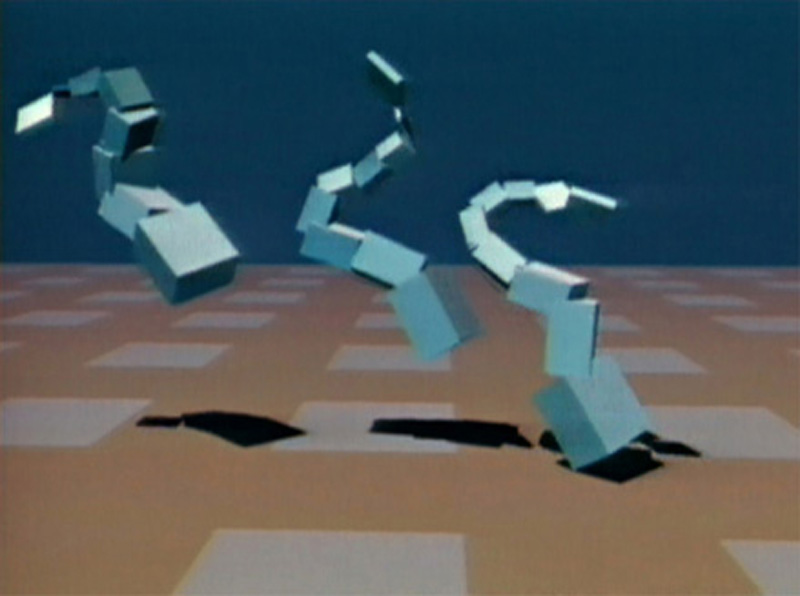

29. Karl Sims's Evolved Virtual Creatures (1994) presents simulated creatures that evolve charming and idiosyncratic methods of locomotion using genetic algorithms.

Additional Projects

- Ian Cheng, Bob (Bag of Beliefs), 2018–2019, animations of evolving artificial lifeforms.

- James Conway, Game of Life, 1970, cellular automaton.

- Sofia Crespo, Neural Zoo, 2018, creatures generated with neural nets.

- Wim Delvoye, Cloaca, 2000–2007, large-scale digestion machine.

- Ulrike Gabriel, Terrain 01, 1993, photoresponsive robotic installation.

- Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. The Substitute, 2019, video installation and animation.

- Edward Ihnatowicz, Senster, 1970, interactive robotic sculpture.

- William Latham, Mutator C, 1993, generated 3D renderings.

- Golan Levin et al., Single Cell and Double Cell, 2001–2002, online bestiary.

- Jon McCormack, Morphogenesis Series, 2002, computer model and prints on photo media.

- Brandon Morse, A Confidence of Vertices, 2008, generated animation.

- Adrià Navarro, Generative Play, 2013, generated characters and card game.

- Jane Prophet and Gordon Selley, TechnoSphere, 1995–2002, online environment and generative design tool.

- Matt Pyke (Universal Everything), Nokia Friends, 2008, generative squishy characters.

- Susana Soares, Upflanze, 2014, hypothetical plant archetypes.

- Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, A-Volve, 1994–1995, interactive installation.

- Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, Lifewriter, 2006, interactive installation.

- Francis Tseng and Fei Liu, Humans of Simulated New York, 2016, participatory economic simulation.

- Juanelo Turriano, Automaton of a Friar, c. 1560, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.

- Jacques de Vaucanson, Canard Digérateur, 1739, automaton in the form of a duck.

- Lukas Vojir, Processing Monsters, 2008–2010, online bestiary.

- Will Wright and Chaim Gingold et al., Spore Creature Creator, 2002–2008, creature construction software.

Readings

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994).

- Valentino Braitenberg, Vehicles: Experiments in Synthetic Psychology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984).

- Bert Wang-Chak Chan, “Lenia: Biology of Artificial Life,” Complex Systems 28, no. 3 (2019), 251–286.

- Ian Cheng et al., Emissaries Guide to Worlding (London: Koenig Books, 2018).

- Craig W. Reynolds, “Steering Behaviors For Autonomous Characters,” Proceedings of the Game Developers Conference (1999), 763–782.

- Daniel Shiffman, The Nature of Code: Simulating Natural Systems with Processing (self-pub., 2012).

- Mitchell Whitelaw, Metacreation: Art and Artificial Life (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006).