Collective Memory

83. In Exhausting a Crowd (2015), Kyle McDonald invites online audiences to annotate a 12-hour video recording of a public place with their own observations of the scene. Inspired by Georges Perec's 1974 experimental literary work An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, McDonald opens up a process of close observation to a broad public, crowdsourcing the discovery and preservation of moments that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Brief

Create an online, open system that invites visitors to collaborate on or contribute to a collectively produced media object. Your project should enable its participants to make changes that persist over time for others to experience (and potentially, modify). The result should be a dynamically evolving visual, textual, sonic, or physical artifact that develops from a novel interaction between friends, siblings, collaborators, neighbors, or strangers. Carefully consider the kinds of actions or authorship you hope to elicit, and how the interaction design of your system influences individual (and hence collective) behavior. Paradoxically, the tightest constraints often produce the most interesting results. Can you create the conditions for unexpected emergent behaviors to arise?

The problem of “bootstrapping” sometimes arises in crowdsourced endeavors where it can be challenging to attract the first wave of participants, particularly if the system does not become interesting until there is significant participation. Does your project need an enlistment strategy?

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate and appraise the aesthetics, design, and concept of systems that support collaboration and emergent creative behavior

- Design an interface, balancing constraints and incentives for participation

- Implement fundamental data structures

Variations

- Consider how (or whether) your system scales. Would your project survive “going viral”?

- Implement a form of automated “weathering,” in which your system gradually organizes, alters, or prunes its participants’ contributions over time.

- Your project may attract trolls, bigots, spammers, bots, vandals, and other visitors acting in bad faith. Be prepared to consider the problem of content moderation (automated or otherwise). Are your users anonymous, or are they somehow accountable?

Making It Meaningful

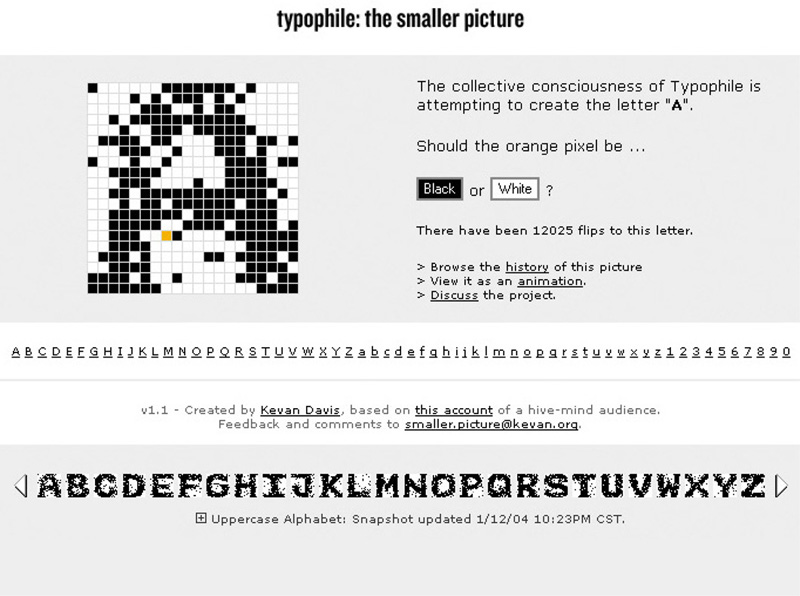

From wasp nests to Wikipedia, principles of emergence explain how the cumulative contributions of thousands of independent agents can produce sophisticated forms. On the Internet, the art of orchestrating large groups of people is called “crowdsourcing,” and the technologies for such information husbandry offer rich opportunities to explore cybernetic concepts like feedback, autopoiesis, and the nuances of collective behavior. The simplest crowdsourcing rulesets can yield a startling glimpse of the consciousness of the global hive-mind, as in Kevan Davis's Typophile: The Smaller Picture (2002), or the epic Place experiment on Reddit (2017). It should surprise no one that crowdsourcing may also channel our darkest impulses, as happened with Microsoft's Tay, an AI chatbot that developed offensive speech patterns through conversations with the crowd.

Collectively created artifacts vary considerably. At one extreme are phenomena, like desire paths or the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, that arise as the inadvertent by-products of myriad human actions. “Memory quilts” and traditional folk songs thread together deliberate contributions from many individuals, but are typically structured according to fixed, widely understood cultural idioms (grids, rhyme schemes, etc.). Other collectively authored artifacts aggregate independent contributions through an undirected process of accumulation; examples of such works include cairns, gum walls, “love padlock” bridges, Yayoi Kusama's Obliteration Room installation, and, on the Internet, graffiti walls like Drawball and SwarmSketch.

Internet artists have enlisted online participants to collaboratively tend gardens, write poetry, produce drawings, interpret imagery, annotate video, and contribute to historical archives. In the genre of the crowdsourced meta-artwork, the creator defines browser-based interactions that scope a user's creative influence—and then distributes artistic agency to a large, open, and often rapidly evolving group. Success depends on carefully balancing constraints (such as limiting available “ink,” or whether or not users are permitted to alter another's contribution) and incentives (such as the opportunity to engage creatively with a favorite song, or participate in a novel creative activity or political action).

84. A cairn is a human-made pile of stones, often accreted over the course of centuries. Since prehistoric times, these collaboratively produced structures have served as landmarks, trail markers, and memorials.

85. Telegarden (1995) by Ken Goldberg and Joseph Santarromana is an interactive networked installation consisting of a garden and a robotic arm. Online visitors view the garden via a webcam, and can plant, water, and tend seedlings by controlling the arm.

86. Roopa Vasudevan's Sluts across America (2012) is a compilation of user-submitted messages advocating for reproductive freedoms, geolocated and displayed on a U.S. map.

87. In Dead Drops (2010), Aram Bartholl creates an offline file-sharing service by covertly mounting USB storage devices throughout a city. If a passerby connects their computer to one of the USB drives, they can download whatever information prior visitors have contributed, or upload new files of their own.

88. Studio Moniker's Do Not Touch (2013) is a crowdsourced music video. Visitors to an interactive web application listen to a song, during which they receive simple instructions on how to move their mouse cursor (“Catch the green dot”). Thus orchestrated, these cursor movements are recorded and then played back in sync with the song.

89. Typophile: The Smaller Picture (2002) is a website by Kevan Davis wherein visitors are prompted to contribute to the design of a letterform, such as the letter ’A’. Each visitor's creative options are tightly restricted: their only choice is to decide whether a given pixel, in a 20x20 grid, should be black or white. The letterform's grid is initialized with random noise. Gradually, as members of the crowd contribute decisions about individual pixels, a collectively designed typeface is produced.

90. Place (shown here in detail) was a 1000x1000 pixel collaborative canvas hosted on Reddit. During a 72-hour period in April 2017, registered users could edit the canvas by selecting the color of a single pixel from a 16-color palette. Because each user could only alter one pixel every five minutes, crowds developed elaborate methods to collectively draw images, write messages, create flags, and overwrite the contributions of others.

91. For the Iyapo Repository (2015), Salome Asega and Ayodamola Okunseinde crowdsource speculations on the future from people of African descent. The artists take the resultant blueprints for cultural technological artifacts, realize them as objects, and acquisition them into the collection.

Additional Projects

- Olivier Auber, Poietic Generator, 1986, contemplative social network game.

- Andrew Badr, Your World of Text, 2009, collaborative online text space.

- Douglas Davis, The World's First Collaborative Sentence, 1994, collaborative online text.

- Peter Edmunds, SwarmSketch, 2005, collaborative online digital canvas.

- Lee Felsenstein, Mark Szpakowski, and Efrem Lipkin, Community Memory, 1973, public computerized bulletin board system.

- Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher, Learning to Love You More, 2002–2009, assignments and crowdsourced responses.

- Agnieszka Kurant, Post-Fordite 2, 2019, fossilized enamel paint sourced from shuttered car manufacturing plants.

- Yayoi Kusama, The Obliteration Room, 2002, interactive installation.

- Mark Napier, net.flag, 2002, online app for flag design.

- Yoko Ono, Wish Tree, 1996, interactive installation.

- Evan Roth, White Glove Tracking, 2007, crowdsourced data collection.

- Jirō Yoshihara, Please Draw Freely, 1956, paint and marker on wood, outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition, Ashiya, Japan.

Readings

- Paul Ryan Hiebert, “Crowdsourced Art: When the Masses Play Nice,” Flavorwire, April 23, 2010.

- Kevin Kelly, “Hive Mind,” in Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, & the Economic World (New York: Basic Books, 1995).

- Ioana Literat, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mediated Participation: Crowdsourced Art and Collective Creativity,” International Journal of Communication 6 (2012): 2962–2984.

- Dan Lockton, Delanie Ricketts, Shruti Chowdhury, and Chang Hee Lee, “Exploring Qualitative Displays and Interfaces” (paper presented at CHI ’17: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, May 2017).

- Trent Morse, “All Together Now: Artists and Crowdsourcing,” ARTnews, September 2, 2014.

- Manuela Naveau, Crowd and Art: Kunst und Partizipation im Internet, Image 107 (Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag, 2017).

- Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

- Clay Shirky, “Wikipedia – An Unplanned Miracle,” The Guardian, January 14, 2011.

- Carol Strickland, “Crowdsourcing: The Art of a Crowd,” Christian Science Monitor, January 14, 2011.

- “When Pixels Collide,” sudoscript.com, 4 April 2017.