Experimental Chat

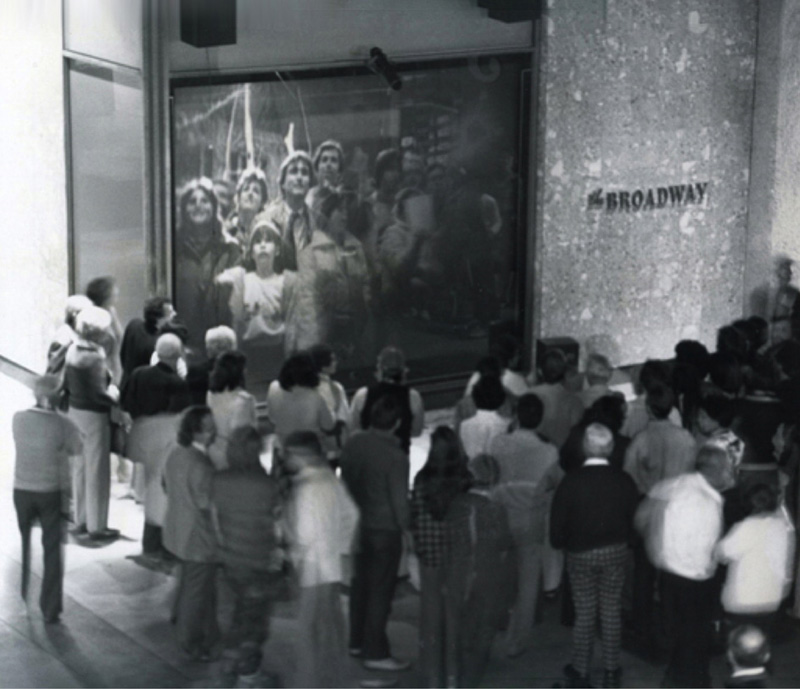

92. Hole in Space (1980), a “communication sculpture” by Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz, used live two-way video to connect street-level pedestrians in Los Angeles and New York City.

Brief

Design a multi-user environment that allows people in different locations to communicate with each other in a new way. Your system could facilitate language-based interactions like typing, speaking, or reading. Alternatively, it could convey non-verbal aspects of presence, such as gestures or breathing, to explore what Heidegger calls Dasein, or “being there together.” Carefully consider the agency of participants in your system, and the timing and directionality of their messages. Are the users passive observers, listening to the murmurings of a crowd, or are they contributors to a grand conversation? Is communication asynchronous, wherein a user's traces are encountered by others later? Or is it synchronous, allowing for simultaneous participation in a live event? Is your system intended for one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, or many-to-many?

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate, discuss, and appraise modalities of verbal and non-verbal communication

- Use a server-client model and a library for real-time networked communication

- Develop, design, and realize a concept for a social space

Variations

- Think beyond your laptop: consider the location(s) where your chat system can be situated, the typical activities people do there, and the relationships they may have. Is your system in a bus station? An orchestra pit? A bedroom? A helmet? Are your participants mutual strangers? Collaborators? Lovers? Parents and their infants?

- Create an environment in which networked users “feel” each other's presence in a novel way.i

- Explore the senses. How might your users communicate with colors? Vibrations? Odors?

- Consider asymmetries of time, scale, agency, or ability. Perhaps one user is limited to communicating with a single fingertip, while the other must use their entire body.

- Create a multiuser environment in which one of the “users” is a crowd (such as a Mechanical Turk workgroup), or an artificial intelligence, such as an ELIZA chatbot, a translation service, Apple Siri, or an automated online assistant.

- Develop a MUD (Multi-User Dungeon), a text-based, multiplayer virtual world. Design a fixed lexicon and syntax of commands for your players, and a task or problem that your players must solve using this vocabulary.

- Use your chat system in a live public performance that incorporates scripted or improvised contributions from both local and remote participants.

Making It Meaningful

Electronic networks provide powerful ways of connecting people who are physically separate. The creation of communication tools (and virtual social spaces) has characterized networked computation since its inception, beginning with the CTSS instant messaging feature (1961), AUTODIN email service (1962), Douglas Engelbart's collaborative real-time text editor (1968), the Talkomatic conferencing system (1973), and multiplayer games like Colossal Cave Adventure (1975).

Computational artists and designers have aimed to expand telecommunication beyond the exchange of character symbols into an experience that employs the full sensory and expressive capabilities of our bodies. Myron Krueger's Videoplace (1974–1990) and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz's Hole in Space (1980) were early systems that took different approaches to full-body telepresence. Today's VR and teledildonics are obvious (and increasingly commercial) extensions of this.

Counterintuitively, some of the most compelling communication systems use strictly limited symbol-sets or rigid constraints on bandwidth. (Consider the telephone, or micro-blogging tools like Twitter.) In the absence of high-resolution sensory information, our imaginations fill in the rest.

93. In The Trace (1995) by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, a participant encounters the moving, ghostlike, real-time “presence” of another person, represented by the glowing intersection of a pair of light-beams. The other person is located in an identical but separate room—and perceives the first participant in the same way.

94. the space between us (2015) by David Horvitz is a mobile app that connects two people's phones. Once connected, the app displays the distance to and direction of the other person.

95. Scott Snibbe's Motion Phone (1995) is a collaborative, multiplayer drawing environment in which participants draw animated forms onto a shared canvas.

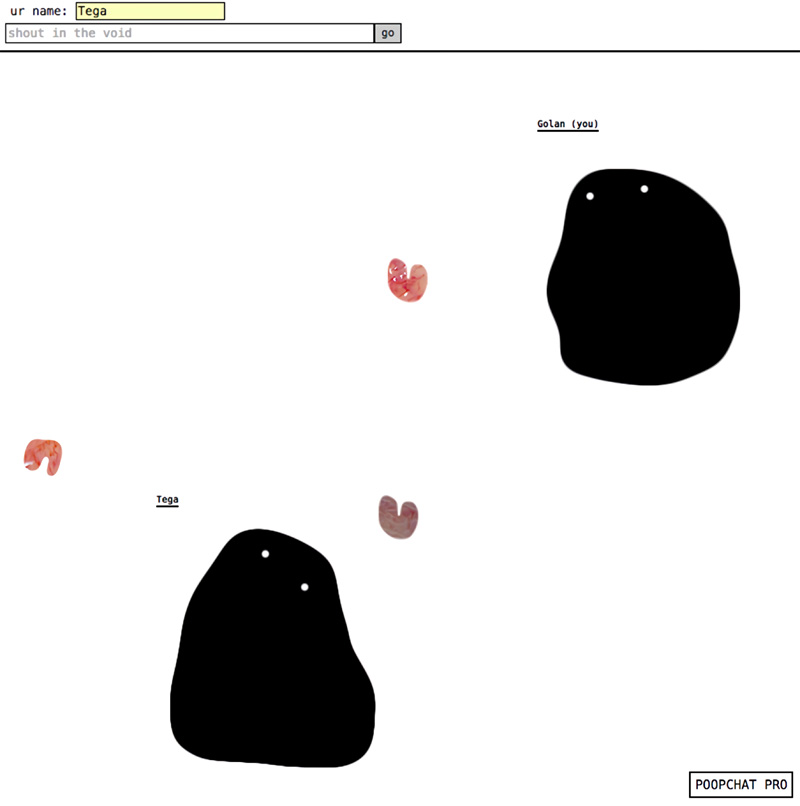

96. Poop Chat Pro (2016) by Maddy Varner is both a real-time chat space and an asynchronous graffiti wall, in which messages are deposited as quivering animations for others to find later.

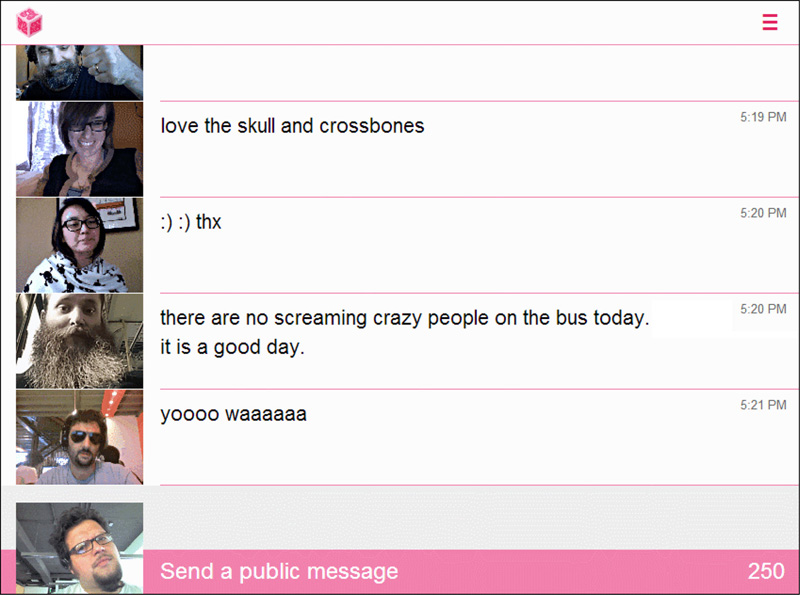

97. Meatspace (2013) by Jen Fong-Adwent and Soledad Penadés is an ephemeral conversation space in which participants’ written messages are accompanied by animated GIF loops, instantaneously captured from their webcams.

98. The Online Museum of Multiplayer Art (2020), a virtual wing of Paolo Pedercini's LIKELIKE neo-arcade, features “playful environments that interrogate our notions of mediated sociality and digital embodiment.” Among the museum's many conceptually oriented chat installations is the “Censorship Room” in which “each word can only be uttered once and never again.”

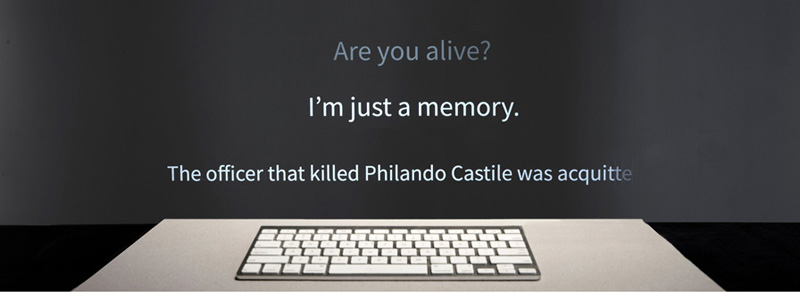

99. American Artist's installation Sandy Speaks (2017) explores the possibilities of chat from beyond the grave. Using a custom-trained AI chatbot, this project places a visitor in conversation with the real words of Sandra Bland, who discussed racism and police brutality in an extensive series of YouTube videos just weeks before her own death in police custody.

Additional Projects

- Olivier Auber, Poietic Generator, 1986, contemplative social network game.

- Wafaa Bilal, Domestic Tension, 2007, interactive video installation.

- Black Socialists of America, BSA's Clapback Chest, 2019, custom search engine.

- Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, Smell Dating, 2016, smell-based dating service.

- Jonah Brucker-Cohen, BumpList, 2003, email list.

- Dries Depoorter and David Surprenant, Die With Me, 2018, mobile chat app.

- Dinahmoe, _plink, 2011, multiplayer online instrument.

- Exonemo, The Internet Bedroom, 2015, online event.

- Zach Gage, Can We Talk?, 2011, chat program.

- Ken Goldberg and Joseph Santarromana, Telegarden, 1995, collaborative garden with industrial robot arm, Ars Electronica Museum, Linz, Austria.

- Max Hawkins, Call in the Night, 2013, phone call service.

- Miranda July, Somebody, 2014, messaging service.

- Darius Kazemi, Dolphin Town, 2017, dolphin- inspired social network.

- Myron Krueger, Videoplace, 1974–1990, multiuser interactive installation.

- Sam Lavigne, Joshua Cohen, Adrian Chen, and Alix Rule, PCKWCK, 2015, digital novel written in real time.

- John Lewis, Intralocutor, 2006, voice-activated installation.

- Jillian Mayer, The Sleep Site, A Place for Online Dreaming, 2013, website.

- Lauren McCarthy, Social Turkers, 2013, system for crowdsourced relationship feedback.

- Kyle McDonald, Exhausting a Crowd, 2015, video with crowdsourced annotations.

- László Moholy-Nagy, Telephone Picture, 1923, porcelain enamel on steel.

- Nontsikelelo Mutiti and Julia Novitch, Braiding Braiding, 2015, experimental publishing project.

- Jason Rohrer, Sleep Is Death (Geisterfahrer), 2010, two-player storytelling game.

- Paul Sermon, Telematic Dreaming, 1992, live telematic video installation.

- Sokpop Collective, sok-worlds, 2020, multiplayer collage.

- Tale of Tales, The Endless Forest, 2005, multiplayer online role-playing game.

- TenthBit Inc., ThumbKiss (renamed as the Couple app), 2013, mobile messaging app.

- Jingwen Zhu, Real Me, 2015, chat app with biometric sensors.

Readings

- Roy Ascott, Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, ed. Edward A. Shanken (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

- Lauren McCarthy, syllabus for Conversation and Computation (NYU, Spring 2015).

- Joanne McNeil, “Anonymity,” in Lurking: How a Person Became a User (New York: Macmillan, 2020).

- Joana Moll and Andrea Noni, Critical Interfaces Toolbox (2016), crit.hangar.org, accessed July 20, 2020.

- Kris Paulsen, Here/There: Telepresence, Touch, and Art at the Interface. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017).

- Casey Reas, “Exercises,” syllabus for Interactive Environments (UCLA D|MA, Winter 2004).