Voice Machine

113. Lynn Hershman Leeson's DiNA, Artificial Intelligent Agent Installation (2002–2004) is an animated, artificially intelligent female character with speech recognition and expressive facial gestures. DiNA converses with gallery guests, generating answers to questions and becoming “increasingly intelligent through interaction.”

Brief

Create an interactive chatbot, eccentric virtual character, or spoken word game centered around computing with speech input and/or speech output. For example, you might make a rhyming game or memory challenge; a voice-controlled book; a voice-controlled painting tool; a text adventure; or an oracular interlocutor (think: Monty Python's Keeper of the Bridge of Death). Consider the creative affordances of using a tightly restricted vocabulary as well as the dramatic potential of rhythm, intonation, and volume of speech. Keep in mind that speech recognition is error-prone, so find ways to embrace the lag and the glitches—at least, for another couple of years. Graphics are optional.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss and explore the expressive possibilities of working with voice and language as a creative medium

- Apply a toolkit for speech recognition and/or speech synthesis

- Design, advance, and execute a concept for a creative work with a voice interface

Variations

- Add speech interactions to an appliance or everyday object. What if your toaster could talk?

- Recall your favorite road-trip word games. Create a competitive, multiplayer speech game in which the computer is the referee.

- Appropriate or subvert a commercial voice assistant as a readymade for a performance.

- Take inspiration from the ways in which pets and babies use speech—often inferring meaning from the tone or prosody of a voice, rather than the words that are spoken. For example, you might make an interactive babbling machine, or a virtual pet that responds to your intonation.

Making It Meaningful

The capacity to speak has long been perceived as a sign of intelligence. For this reason, machines that speak can seem uncanny or even supernatural, as they decouple ancient bindings between voice, living matter, and intelligence. In the field of interaction design, voice interfaces are thought to make technologies more intuitive and accessible than their visual or typographic counterparts—but such anthropomorphized machines do this at the expense of our ability to accurately estimate how much they actually “understand.”

In a conversation, information is transmitted and received on multiple registers—in not only what is said, but also how it is delivered, and by whom. We have exquisitely tuned capacities for inferring contextual information like emotion, gender, age, health, and socioeconomic status from a speaking voice. Intonation, rhythm, pace, and rhyme are also used to create drama, suspense, sarcasm, and humor. When creating new experiences through speech, simple operations may be the most generative. For example, a vast range of meanings can arise just from altering the emphasis of words in a sentence.

Speech has a key paralinguistic social role. Through chit-chat and banter we establish trust, build relations, and create intimacy. Wordplay, punnery, and other playful verbal exchanges create a protected space for this social activity by exploiting ambiguities in the rules of language itself. Culture is embedded and propagated in the protocols of knock-knock jokes, call-and-response songs, and once-upon-a-time fairy tales. These rule-based media lend themselves well to creative manipulation with code. Some potentially helpful tools to algorithmically generate speech include context-free grammars, Markov chains, recurrent neural nets (RNN), and long short-term memory (LSTM) systems. Note that some commercial speech analysis tools transmit the users’ voice data to the cloud, raising issues of data ownership and privacy.

114. In Conversations with Bina48 (2014), Stephanie Dinkins performs improvised conversations about algorithmic bias with BINA48, a chatbot-enabled face robot. BINA48 was commissioned by entrepreneur Martine Rothblatt, and constructed by roboticist David Hanson, to resemble Rothblatt's wife Bina.

115. Hey Robot (2019) by Everybody House Games is a game in which teams compete to make a smart home assistant (such as Amazon Alexa or Google Home) say specific words.

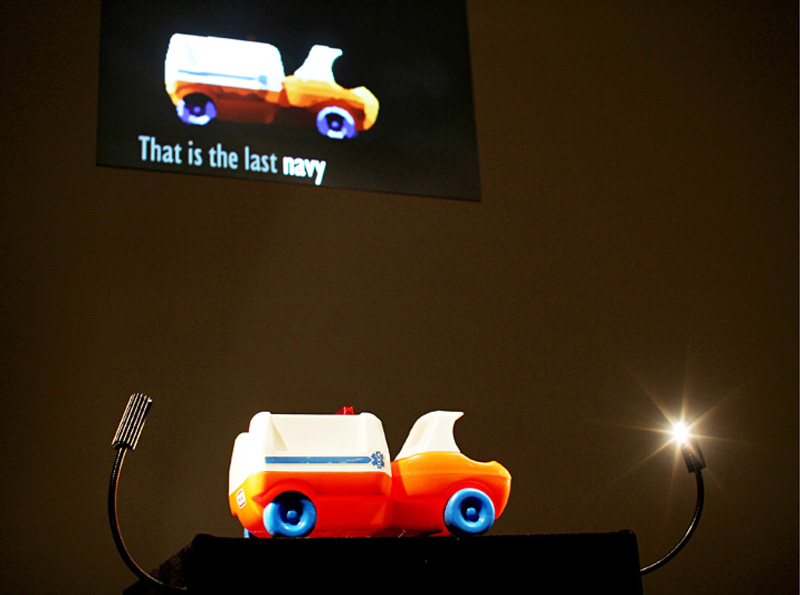

116. In David Rokeby's The Giver of Names (1991–1997), a camera detects objects placed on a pedestal by members of the audience. A computerized voice then describes what it sees—with strange, uncanny, and often poetic results.

117. When Things Talk Back (2018), by Roi Lev and Anastasis Germanidis, is a mobile AR app that gives voice to everyday objects. The software automatically identifies objects observed by the system's camera, and anthropomorphizes them with AR overlays of simple faces. It then uses ConceptNet, a freely available semantic network, to retrieve information about the objects and their possible interrelationships. The app uses this information to generate humorous and sometimes poignant conversations between the objects in the scene.

118. David Lublin's Game of Phones (2012) is “the children's game of telephone, played by telephone.” Players receive a phone call and hear a prerecorded message left by the previous player; they are then prompted to re-record what they recall hearing for the next person in the queue. After a week, the entire chain of messages is published online.

119. Neil Thapen's playful Pink Trombone (2017) is an interactive articulatory speech synthesizer for “bare-handed speech synthesis.” Using a richly instrumented simulation of the human vocal tract, the project enables a wide range of vocal noisemaking in the browser.

120. Kelly Dobson's Blendie (2003–2004) is a 1950s Osterizer blender, adapted to respond empathetically to a user's voice. A person induces the blender to spin by vocalizing. Blendie then mechanically mimics the person's pitch and power level, from a low growl to a screaming howl.

121. In Nicole He's speech-driven forensics game, ENHANCE.COMPUTER (2018), players yell out commands like “Enhance!”—living out a science-fiction fantasy of infinitely zoomable images.

Additional Projects

- Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling, Zork, 1977–1979, interactive text-based computer game.

- Isaac Blankensmith with Smooth Technology, Paper Signals, 2017, system for making voice-controlled paper objects.

- Mike Bodge, Meme Buddy, 2017, voice-driven app for generating memes.

- Stephanie Dinkins, Not The Only One, 2017–2019, voice-driven sculpture trained on oral histories.

- Homer Dudley, The Voder, 1939, device to electronically synthesize human speech.

- Ken Feingold, If/Then, 2001, sculptural installation with generated dialogue.

- Sidney Fels and Geoff Hinton, Glove Talk II, 1998, neural network-driven interface translating gesture to speech.

- Wesley Goatly, Chthonic Rites, 2020, narrative installation with Alexa and Siri.

- Suzanne Kite, Íŋyaŋ Iyé (Telling Rock), 2019, voice-activated installation.

- Jürg Lehni, Apple Talk, 2002–2007, computer interaction via text to speech and voice recognition software.

- Golan Levin and Zach Lieberman, Hidden Worlds of Noise and Voice, 2002, sound-activated augmented reality installation, Ars Electronica Futurelab, Linz.

- Golan Levin and Zach Lieberman with Jaap Blonk and Joan La Barbara, Messa di Voce, 2003, voice-driven performance with projection.

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Voice Tunnel, 2013, large-scale interactive installation in the Park Avenue Tunnel, New York City.

- Lauren McCarthy, Conversacube, 2010, interactive conversation-steering devices.

- Lauren McCarthy, LAUREN, 2017, smart home performance.

- Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen, Listening Post, 2002, installation displaying and voicing real-time chatroom utterances.

- Harpreet Sareen, Project Oasis, 2018, interactive weather visualization and self-sustaining plant ecosystem.

- Superflux, Our Friends Electric, 2017, film.

- Joseph Weizenbaum, ELIZA, 1964, natural language processing program.

Readings

- Zed Adams and Shannon Mattern, “April 2: Contemporary Vocal Interfaces,” readings from Thinking through Interfaces (The New School, Spring 2019).

- Takayuki Arai et al., “Hands-On Speech Science Exhibition for Children at a Science Museum” (paper presented at WOCCI 2012, Portland, OR, September 2012).

- Melissa Brinks, “The Weird and Wonderful World of Nicole He's Technological Art,” Forbes, October 29, 2018.

- Geoff Cox and Christopher Alex McLean, “Vocable Code,” in Speaking Code: Coding as Aesthetic and Political Expression (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 18–38.

- Stephanie Dinkins, “Five Artificial Intelligence Insiders in Their Own Words,” New York Times, October 19, 2018.

- Andrea L. Guzman, “Voices in and of the Machine: Source Orientation toward Mobile Virtual Assistants,” Computers in Human Behavior 90 (2019): 343–350.

- Nicole He, “Fifteen Unconventional Uses of Voice Technology,” Medium.com, November 26, 2018.

- Nicole He, “Talking to Computers” (lecture, awwwards conference, New York, NY, November 28, 2018).

- Halcyon M. Lawrence, “Inauthentically Speaking: Speech Technology, Accent Bias and Digital Imperialism” (lecture, SIGCIS Command Lines: Software, Power & Performance, Mountain View, CA, March 2017), video, 1:26–17:16.

- Halcyon M. Lawrence and Lauren Neefe, “When I Talk to Siri,” TechStyle: Flash Readings 4 (podcast), September 6, 2017, 10:14.

- Shannon Mattern, “Urban Auscultation; or, Perceiving the Action of the Heart,” Places Journal, April 2020.

- Mara Mills, “Media and Prosthesis: The Vocoder, the Artificial Larynx, and the History of Signal Processing,” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences 21, no. 1 (2012): 107–149.

- Danielle Van Jaarsveld and Winifred Poster, “Call Centers: Emotional Labor over the Phone,” in Emotional Labor in the 21st Century: Diverse Perspectives on Emotion Regulation at Work, ed. Alicia A. Grandey, James M. Diefendorff, and Deborah E. Rupp (New York: Routledge, 2012): 153–73.

- “Vocal Vowels,” Exploratorium Online Exhibits, accessed April 14, 2020.

- Adelheid Voshkul, “Humans, Machines, and Conversations: An Ethnographic Study of the Making of Automatic Speech Recognition Technologies,” Social Studies of Science 34, no. 3 (2004).