Virtual Public Sculpture

150. Keiichi Matsuda's HYPER-REALITY (2016) is a richly detailed short film that anticipates a dystopic near-future of ubiquitous AR advertising, gamified consumerism, and corporate surveillance.

Brief

Robert Smithson has remarked that “the site is a place where a piece should be but isn't.” In this assignment, you are asked to create the missing piece for a site using augmented reality (AR). More specifically: place and view a virtual object of your choice, at a scale of your choice, in a physical location of your choice, with a programmatic behavior of your choice.

When choosing your site, consider the conceptual and aesthetic opportunities offered by its location and history, as well as the ways in which it is occupied. Write down some observations about who uses the site, and how. Your location may be public, generic, or private. For example, it could be a prominent landmark, an unspecified supermarket aisle, your bedroom, or even the palm of your hand.

Your virtual object may be appropriated, downloaded, recycled, modeled, or scanned. You might conceive of your object as a “sculpture,” “monument,” “installation,” or “decoration,” or as something else entirely (“anomaly,” “natural formation”). Write some code that makes it behave in a certain way. For example, it could rotate slowly in place, emit a shower of particles, or change size whenever the viewer gets close.

Assume that your intervention will be viewed on a mobile device or tablet. Document your project in video, capturing both “over-the-shoulder” and “through-the-device” perspectives. Your documentation should convey how an audience would experience your artwork. How does your project change and reflect relationships between physical and virtual, public and private, screen and site? Publish your intervention, and its documentation, so that it can be shared with others.

Learning Objectives

- Develop, design, and execute a creative intervention at a specific site

- Review the technical requirements and workflow of augmented reality

- Plan and create documentation of augmented reality projects

Variations

- Develop and enact a performance that makes use of your virtual object.

- Create an intervention that appears to remove an object, rather than adding one.

- Design an experience that connects both a virtual intervention (in AR) and a real, physical intervention (such as a prop) of your own design.

- “Gamify” your site with augmented reality objects that turn it into an obstacle course, treasure hunt, escape room, playing field, or game board.

- Research the history or current use of the site, and develop an augmentation that uses data derived from this place. Examples of data might include statistics about power consumption or pollution, architectural or geologic features, historic photographs, audio clips of interviews, or real-time weather information.

Making It Meaningful

Augmented reality (AR) adds a layer of virtual information to the world. Media like 3D animations, text, or images can be anchored to locations, landscape features subtracted, and the world distorted. Whereas public artworks are sometimes criticized for their lack of engagement with the concerns of local communities (and scathingly derided as “plop art”), public artworks in AR offer opportunities to counter this criticism with their potential to be dynamic, interactive, and mutable by audiences. Situated in public space, AR artworks bring together the expressive languages and critical traditions of public art, street performance, graffiti, and video games.

Advertising, branding, and other corporate media are ready targets for unsanctioned activist interventions using AR. As Banksy urges, “Any advert in a public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours….You can do whatever you like with it. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head.” i AR in public space offers the possibility of articulating or even prototyping new power relationships in ways that would be impossible within the controlled channels of institutions and mass media. As Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking demonstrate in The Leak in Your Hometown (2010), one strategy to give interventions wide traction is to use well-known logos or other ubiquitous symbols as visual “anchors” (targets) for critical augmentation, enabling a project to become “site-specific” in any place featuring that sign. For the purposes of culture jamming and design activism, which aim to reframe issues and shift opinion through the viral manipulation of media, this combination of Internet-distributed apps with a savvy selection of AR anchors can be particularly effective.

This prompt is similar to the Augmented Projection assignment, in that both invite the artist to create a dynamic virtual addition to a specific site. In both, the challenge is to design interventions that are tightly coupled to their contexts. There are, however, some key differences. Where projections operate like painting, obeying logics of representation, abstraction, and illusion, augmented reality is more akin to sculpture, deploying objects that do not represent, but simply exist in space. Formally speaking, augmented reality does not require a projection surface, making it possible to suspend AR objects in mid-air or have them move around the viewer. Likewise, 3D forms in AR can exist at any apparent scale, from palm-sized to sky-filling, and can even appear behind or inside real-world objects (as with an X-ray). Taken together, these properties of AR allow for new ways of choreographing the actions and movements of audiences. Finally, the distributed nature of AR displays also means that people in the same place can see different things, or (as Skwarek and Hocking show) people in different places can see the same thing.

For better or worse, augmented worlds observed through phones, tablets, and goggles are not universally viewable, and must be actively experienced by participants who are in on the joke—in what are ultimately private views in a public space. This hyper-individual nature of AR may eventually have unforeseen political consequences, such as digital redlining, the creation of filter bubbles, and the amplification of radical views.

151. Jeffrey Shaw's Golden Calf (1994) was a pioneering work of augmented reality. Using a handheld LCD screen fitted with a Polhemus position tracking system, viewers could observe a virtual 3D sculpture of a golden calf hovering above an otherwise empty pedestal.

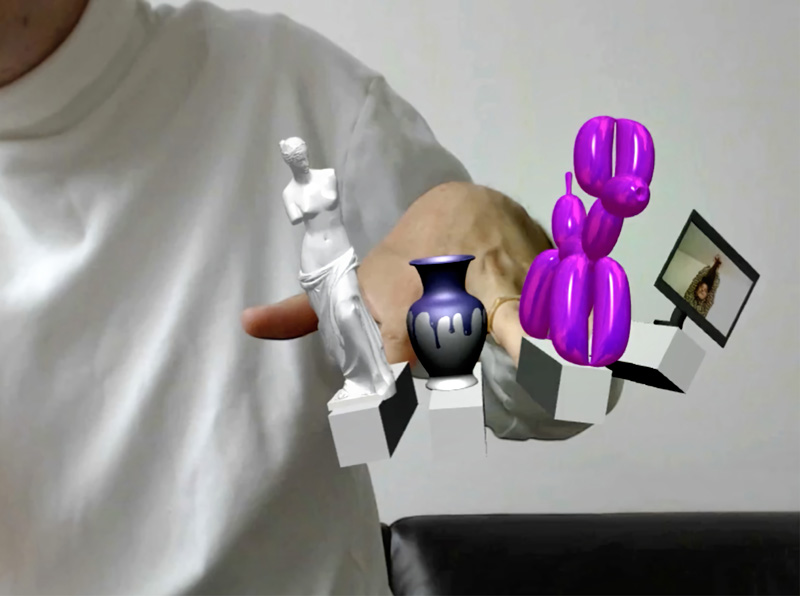

152. Nail Art Museum (2014) by Jeremy Bailey is a tiny virtual museum in which canonical works of art appear positioned on finger-mounted plinths.

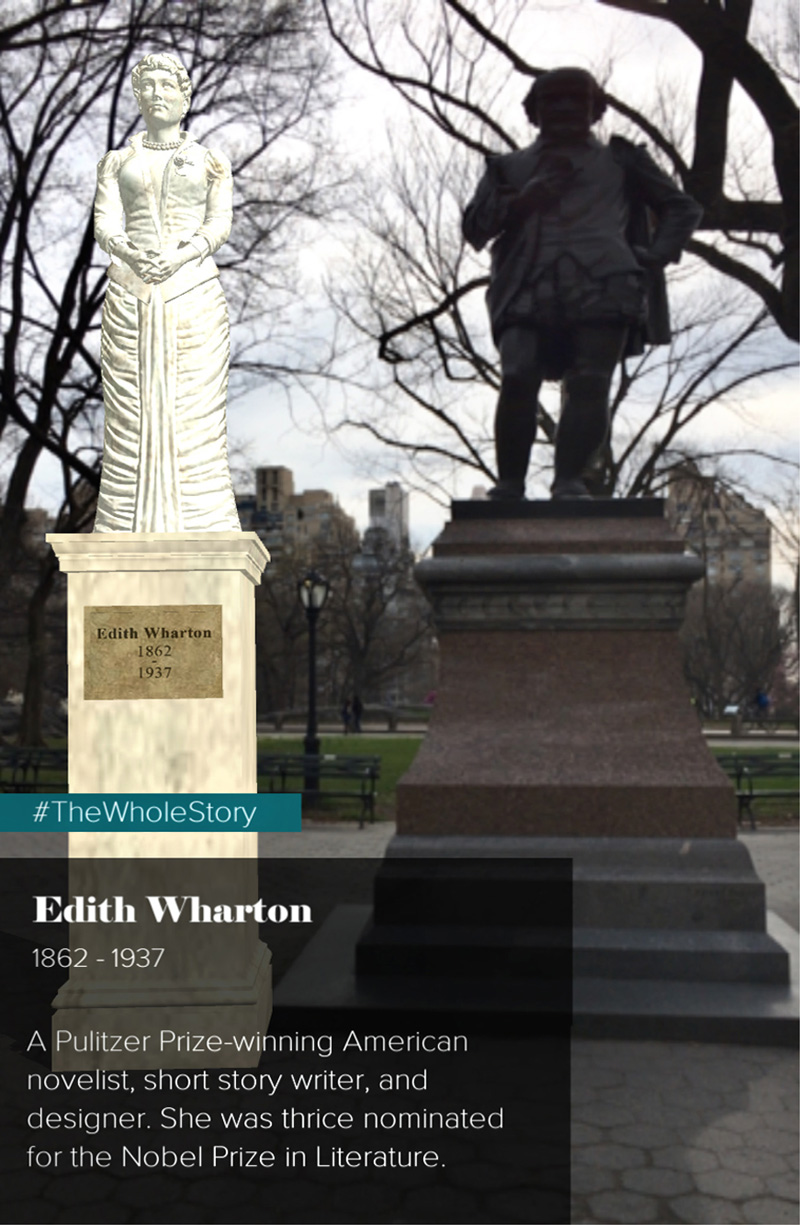

153. The Whole Story (2017) by Y&R New York aims to address gender parity in public monuments by allowing users to view, share, and add virtual statues of notable women alongside existing public statuary.

154. Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking created The Leak in Your Hometown (2010) in response to the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The augmented reality smartphone app anchors an animation of a leaking oil pipe to any BP logo.

155. Nathan Shafer's Exit Glacier project (2012) is a site-specific smartphone app that depicts the historic extent of the Exit Glacier in the Kenai Mountains of Alaska, visualizing glacial recession due to climate change.

156. Augmented Nature (2019) by Anna Madeleine Raupach uses natural objects like trees, stumps, and lichen-covered rocks as anchors for poetic site-specific animations.

Additional Projects

- Awkward Silence Ltd, Pigeon Panic AR, 2018, augmented reality pigeon game app.

- Aram Bartholl, Keep Alive, 2015, outdoor boulder installation with fire-powered WiFi and digital survival guide repository.

- Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, Alter Bahnhof Video Walk, 2012, augmented reality walking tour of the Alter Bahnhof, Kassel, Germany.

- Carla Gannis, Selfie Drawings, 2016, artist book with AR experiences.

- Sara Hendren and Brian Glenney, Accessible Icon Project, 2016, icon and participatory public intervention.

- Jeff Koons, Snapchat: Augmented Reality World Lenses, 2017, augmented reality public sculpture installations.

- Zach Lieberman and Molmol Kuo, Weird Type, 2018, augmented reality text app.

- Lily & Honglei (Lily Xiying Yang and Honglei Li), Crystal Coffin, 2011, AR app, virtual China Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale.

- Jenny Odell, The Bureau of Suspended Objects, 2015, archive of discarded belongings.

- Julian Oliver, The Artvertiser, 2008, AR app for advertisement replacement.

- Damjan Pita and David Lobser, MoMAR, 2018, AR art exhibition.

- Mark Skwarek, US Iraq War Memorial, 2012, participatory AR memorial.

Readings

- AtlasObscura.com, “Unusual Monuments,” accessed April 14, 2020.

- Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper, Subway Art, 2nd ed. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2016).

- Vladimir Geroimenko, ed., Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium, 2nd ed. (New York: Springer, 2018).

- Sara Hendren, “Notes on Design Activism,” accessibleicon.org, last modified 2015, accessed April 14, 2020.

- Josh MacPhee, “Street Art and Social Movements,” Justseeds.org, last modified February 17, 2019, accessed April 14, 2020.

- Ivan Sutherland, “The Ultimate Display,” Proceedings of the IFIP Congress 65, vol. 1 (London: Macmillan and Co., 1965): 506–508.