Extrapolated Body

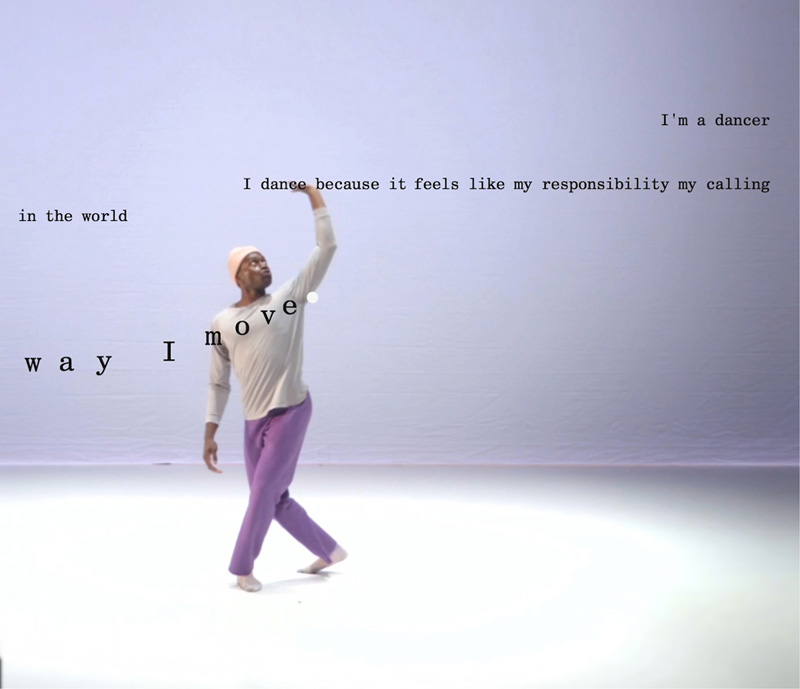

157. Using pose estimation and speech recognition technologies, choreographer Bill T. Jones collaborated with Google Creative Lab to produce Body, Movement, Language (2019), a series of interaction studies in which participants can use their bodies to position their own spoken words in the space around them.

Brief

Create a virtual mask or costume, and use it in a performance.

In this assignment, you are asked to write software that creatively interprets or responds to the movements of your face or body, as observed by a motion capture or computer vision system. More precisely: develop a computational treatment of spatiotemporal data captured from a person, such as the coordinates of features on their face, the 3D locations of their joints, or points along the 2D contour of their silhouette.

Consider whether your treatment serves a ritual purpose, a practical purpose, or works to some other end. It may visualize or obfuscate your personal information. It may allow you to assume a new identity, including something nonhuman or even inanimate. It may have articulated parts and dynamic behaviors. It may be part of a game. It may blur the line between self and others, or between self and not-self.

Depending on the materials at hand, your system may use a standard webcam or a specialized peripheral (like a Kinect depth sensor). Furthermore, your solution may require you to learn how to use APIs for real-time face tracking or pose estimation, receive and interpret data transmitted by precompiled body-tracking apps (e.g., via OSC), or record and interpret data from a professional mocap system.

Design your software for a specific performance, and plan your performance with your software in mind; be prepared to explain your creative decisions. Rehearse and record your performance.

Learning Objectives

- Survey the tools and workflows for motion capture

- Use algorithmic techniques to develop a visual interpretation of motion data

- Explore aesthetic and conceptual possibilities in animating human form and movement

Variations

- Instructors: It is helpful to provide students with a code template for a tracking library, such as PoseNet (via ml5.js) or FaceOSC. In so doing, this assignment may be restricted to just the face or body.

- You may perform your project yourself, or you may collaborate with any performer available to you. Is your software intended for a person with highly specialized movement skills (dancer, musician, athlete, actor), or can anyone operate it?

- The assignment brief poses the problem of creating interactive software that responds to real-time data. Instead, generate an animation using pre-recorded (offline) motion capture data. Create or select this data carefully. You might record data yourself, if you have access to a motion capture studio; use mocap data from an online source (such as a research archive or commercial vendor); or creatively augment a favorite YouTube video with the help of a pose estimation library.

- Remember that you may position your virtual “camera” anywhere; your motion capture data need not be displayed from the same point of view as your sensor. Consider rendering your performer's body from above, from a moving location, or even from their own point of view.

- In contrast to an expressive concept (such as a character animation or playful interactive mirror), develop an analytic treatment, such as an information visualization, that diagrams and compares the movements of body joints or facial landmarks over time. For example, your software could present comparisons between different people making similar expressions, or it could provide insight into the articulations of movements by a violinist.

- Consider using sound synchronized to your motion capture data. This sound might be the performer's speech, music to which they are dancing, or sounds synthetically generated by their movements.

- Rather than depicting the body itself, write software to visualize how an environment is disturbed by a body, as with footprints in sand.

- Use your face or body to puppeteer something nonhuman: a computer-generated animal, monster, plant, or customarily inanimate object.

- Visualize a relationship between two or more performers’ bodies.

- Focus on the actions of a single part of the body or face.

Making It Meaningful

Costumes, masks, cosmetics, and digital face filters allow the wearer to fit in or act out. We dress up, hide or alter our identity, play with social signifiers, or express our inner fursona. We use them to ritualistically mark life events or spiritual occasions, or simply to obtain “temporary respite from more explicit and determinate forms of sociality, freeing us to interact more imaginatively and playfully with others and ourselves.” i

Many innovations in understanding, visualizing, and augmenting the dynamic human body originate as analytic tools (most often, for military purposes) that are then creatively repurposed as expressive ones (for the arts and entertainment). The effect of this evolution is that scientific techniques for capturing body movement, such as Étienne-Jules Marey's chronophotography, contribute to the development of new artistic languages, such as Marcel Duchamp's Cubist abstraction. Additional examples include the motion capture suit, first developed by Marey in 1883 in physiological research on soldier movement, and the technique of what is now called “light painting” (long-exposure photographs of lights attached to moving bodies), explored in depth in 1914 by Frank and Lillian Gilbreth to analyze and optimize the activities of soldiers and workers.

Body movement is an important dimension of storytelling, central to the vocabularies of performance and dance, and also to those of animation and puppeteering, where it is essential to creating the illusion of life. As Alan Warburton explains, animators develop character by “creating an equivalence between who someone is, and how they move…. Any audience should know instantly who a character is just from their motion.” ii This conflation of how we look and move and who we are is also a foundational premise of video surveillance technologies—which, extending from problematic disciplines like physiognomy, phrenology, and somatotypology, aim to deduce a subject's moral character from their outward appearance.

The face, with its significant role in identity and communication,iii is of particular focus in carceral technologies. Facial recognition systems are perilous for many reasons: they enable automated nonconsensual identification and are therefore ripe for misuse in the context of policing and authoritarian regimes; they operate with the allure of objectivity despite being prone to catastrophic inaccuracies; they are difficult to audit and contest by those they impact most; and their use is often invisible. On the flip side, face trackers have also been used for expressive, entertaining, and educational purposes. They serve as digital masks and face filters; as controllers for games (as in Elliott Spelman's “eyebrow pinball” game, Face Ball); as musical interfaces (Jack Kalish's Sound Affects performance); as controllers for richly parameterized graphic designs (Mary Huang's typographic TypeFace); as a means for furthering public understanding of surveillance technologies (Adam Harvey's CV Dazzle); and as tools for interrogating contemporary culture (Christian Moeller's Cheese or Hayden Anyasi's StandardEyes). In working with computational face and body tracking libraries, media artists and interface designers are encouraged to reflect on the origins of their tools, and the extent to which their use in a creative work reinforces the teleology of carceral surveillance systems. How might creative engagements activate what Ruha Benjamin calls “a liberatory imagination,” where the goal is to illuminate or circumvent these mechanisms and envisage a more just, egalitarian, and vibrant world?iv

158. In partnership with the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Memo Akten and Davide Quayola developed Forms, a series of abstract 3D visualizations of athletes’ trajectories and mechanics.

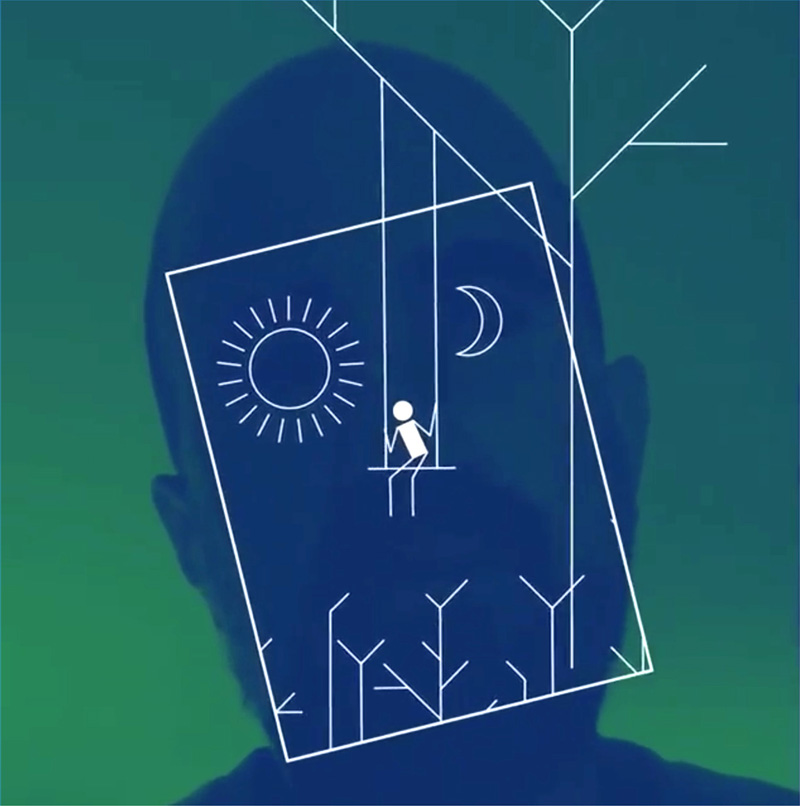

159. Referencing the utopian formalism of 1960s architecture, Walking City (2014) by Universal Everything is a “slowly evolving video sculpture” structured around a cycle of human locomotion.

160. While students at the University of Paris 8, Sophie Daste, Karleen Groupierre, and Adrien Mazaud developed Miroir (2011), an interactive installation in which a spectator sees a ghostly animal head superimposed onto the reflection of their own face. The anthropomorphized double closely follows their movements and expressions.

161. Más Que la Cara (2016), a street-level interactive installation by YesYesNo, presents imaginative, poster-like interpretations of spectators’ faces.

Additional Projects

- Jack Adam, Tiny Face, 2011, face measurement app.

- Rebecca Allen, Catherine Wheel, 1982, computer-generated character.

- Hayden Anyasi, StandardEyes, 2016, interactive art installation.

- Nobumichi Asai, Hiroto Kuwahara, and Paul Lacroix, OMOTE, 2014, real-time tracking and facial projection mapping.

- Jeremy Bailey, The Future of Marriage, 2013, software.

- Jeremy Bailey, The Future of Television, 2012, software demo.

- Jeremy Bailey, Suck & Blow Facial Gesture Interface Test #1, 2014, software test.

- Jeremy Bailey and Kristen D. Schaffer, Preterna, 2016, virtual reality experience.

- Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization Suite, 2011–2014, masks digitally modeled from aggregate data.

- Nick Cave, Sound Suits, 1992–, wearable sculptures.

- A. M. Darke, Open Source Afro Hair Library, 2020, 3D model database.

- Marnix de Nijs, Physiognomic Scrutinizer, 2008, interactive installation.

- Arthur Elsenaar, Face Shift, 2005, live performance and video.

- William Fetter, Boeing Man, 1960, 3D computer graphic.

- William Forsythe, Improvisation Technologies, 1999, rotoscoped video series.

- Daniel Franke and Cedric Kiefer, unnamed soundsculpture, 2012, virtual sculpture using volumetric video data.

- Tobias Gremmler, Kung Fu Motion Visualization, 2016, motion data visualization.

- Paddy Hartley, Face Corset, 2002–2013, speculative fashion design.

- Adam Harvey, CV Dazzle, 2010–, counter-surveillance fashion design.

- Max Hawkins, FaceFlip, 2011, video chat add-on.

- Lingdong Huang, Face-Powered Shooter, 2017, facially controlled game.

- Jack Kalish, Sound Affects, 2012, face-controlled instruments and performance.

- Keith Lafuente, Mark and Emily, 2011, video.

- Béatrice Lartigue and Cyril Diagne, Les Métamorphoses de Mr. Kalia, 2014, interactive installation.

- David Lewandowski, Going to the Store, 2011, digital animation and video footage.

- Zach Lieberman, Walk Cycle / Circle Study, 2016, computer graphic animation.

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, The Year's Midnight, 2010, interactive installation.

- Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald, How We Act Together, 2016, participatory online performance.

- Kyle McDonald, Sharing Faces, 2013, interactive installation.

- Christian Moeller, Cheese, 2003, smile analysis software and video installation.

- Nexus Studio, Face Pinball, 2018, game with facial input.

- Klaus Obermaier with Stefano D’Alessio and Martina Menegon, EGO, 2015, interactive installation.

- Orlan, Surgery-Performances, 1990–1993, surgical operations as performance.

- Joachim Sauter and Dirk Lüsebrink, Iconoclast / Zerseher, 1992, eye-responsive installation.

- Oskar Schlemmer, Slat Dance, 1928, ballet.

- Karolina Sobecka, All the Universe Is Full of the Lives of Perfect Creatures, 2012, interactive mirror.

- Elliott Spelman, Expressions, 2018, face-controlled computer input system.

- Keijiro Takahashi, GVoxelizer, 2017, animation software tool.

- Universal Everything, Furry's Posse, 2009, digital animation.

- Camille Utterback, Entangled, 2015, interactive generative projection.

- Theo Watson, Autosmiley, 2010, whimsical vision-based keyboard automator.

- Ari Weinkle, Moodles, 2017, animation.

Readings

- Greg Borenstein, “Machine Pareidolia: Hello Little Fella Meets Facetracker,” Ideas for Dozens (blog), UrbanHonking.com, January 14, 2012.

- Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, Gender Shades, 2018, research project, dataset, and thesis.

- Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, “Excavating AI: The Politics of Images in Machine Learning Training Sets, excavating.ai, September 19, 2019.

- Regine Debatty, “The Chronocyclegraph,” We Make Money Not Art (blog), May 6, 2012.

- Söke Dinkla, “The History of the Interface in Interactive Art,” kenfeingold.com, accessed April 17, 2020.

- Paul Gallagher, “It's Murder on the Dancefloor: Incredible Expressionist Dance Costumes from the 1920s,” DangerousMinds.net, May 30, 2019.

- Ali Gray, “A Brief History of Motion-Capture in the Movies,” IGN, July 11, 2014.

- Katja Kwastek, Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

- Daito Manabe, “Human Form and Motion,” GitHub, updated July 5, 2018.

- Kyle McDonald, “Faces in Media Art,” GitHub repository for Appropriating New Technologies (NYU ITP), updated July 12, 2015.

- Kyle McDonald, “Face as Interface,” 2017, workshop.

- Jason D. Page, “History,” LightPaintingPhotography.com, accessed April 17, 2020.

- Shreeya Sinha, Zach Lieberman, and Leslye Davis, “A Visual Journey Through Addiction,” New York Times, December 18, 2018.

- Scott Snibbe and Hayes Raffle, “Social Immersive Media: Pursuing Best Practices for Multi-User Interactive Camera/Projector Exhibits,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2009).

- Nathaniel Stern, Interactive Art and Embodiment: The Implicit Body as Performance (Canterbury, UK: Gylphi Limited, 2013).

- Alexandria Symonds, “How We Created a New Way to Depict Addiction Visually,” New York Times, December 20, 2018.

- Alan Warburton, Goodbye Uncanny Valley, 2017, animation.