Synesthetic Instrument

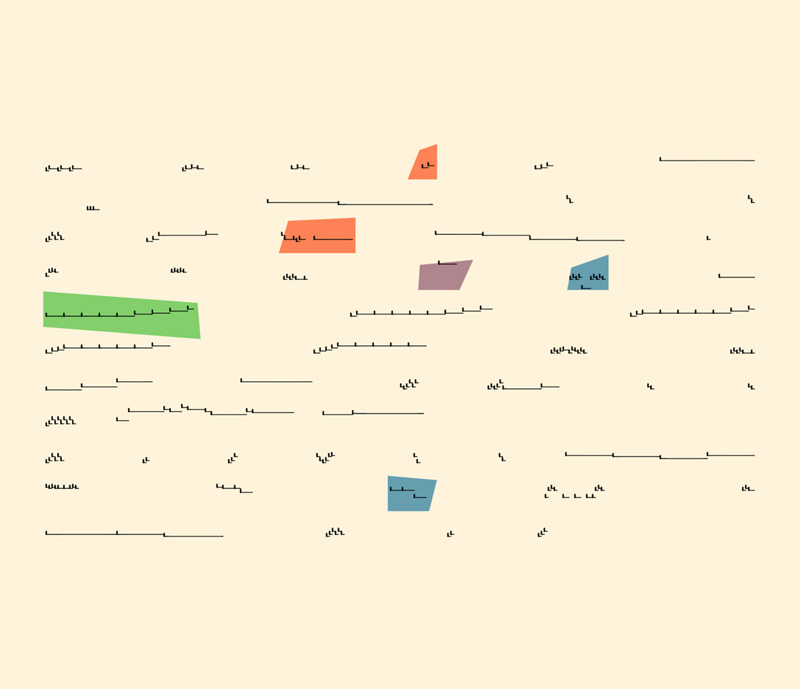

162. In the Web-based performance In C (2015) by Luisa Pereira, Yotam Mann, and Kevin Siwoff, a group of performers use mice and keyboards to control the pace at which their individual instruments advance through a graphical score, producing highly variable musical results.

Brief

Create an “audiovisual instrument” that allows a performer to produce tightly coupled sound and visuals. Your software should make possible the creation of both dynamic imagery and noise/sound/music, simultaneously, in real time.

You are challenged to create an open-ended system in which sonic and visual modalities are equally expressive. Its results should be inexhaustible, deeply variable, and contingent on the performer's choices, and the basic principles of its operation should be easy to deduce, yet also allow for sophisticated expression. Interactions with your instrument should generate predictable results.

Assume your instrument receives input from the actions and gestures of a performer. Will they use a keyboard, mouse, multi-touch trackpad, pose tracker, or a less common sensor? Select (or construct) your instrument's physical interface with care, giving consideration to its expressive affordances. Categorize the data streams it provides: are these continuous values, or changes in logical states? Do they have a perceptible duration, and are they persistent or instantaneous? Are they one-, two-, three-, or four-dimensional?

Assume your instrument generates output for a graphic display and audio system. Think through the possibilities offered by different visual variables like hue, saturation, texture, shape, and motion, and different auditory elements including pitch, dynamics, timbre, scales, and rhythm. Link these sonic and visual elements together by establishing mappings between your system's input and output. For example: the faster the performer moves her cursor, the brighter her cursor appears, and the higher the pitch of a synthesized tone. Such mappings help set up expectations that can be manipulated by a performer to create contrast, tension, surprise, and even humor.

Attune us to your instrument's unique expressive qualities by using it in a brief performance. One suggestion for structuring this performance is to begin with an expository demonstration of your instrument's interface, guiding the audience into understanding how it operates before presenting more complex material. The repetition and subsequent elaboration of themes is also a helpful compositional strategy.

Learning Objectives

- Review historical precedents in audiovisual instrument design

- Explore ways to control and connect sound and visuals

- Review and implement event-driven programming

- Apply interaction design principles to the development of performance instruments, with special attention to a system's responsiveness, predictability, ease of use, and interface

Variations

- Instructors: require all students to use the same type of physical interface (such as a game controller, pressure-sensitive stylus, or barcode reader). This will allow them to better contrast their solutions.

- Develop a “QWERTY instrument” that is wholly played through typed actions on a standard computer keyboard. This simplified format can helpfully limit your design to the use of discrete inputs (button presses, rather than continuous gestures), and discrete outputs (triggering pre-recorded and pre-rendered media, rather than synthesizing sounds and graphics through the real-time modulation of continuous parameters). Embed your project in a web page and publish it online. Consider how the provenance of your sounds and images can enrich your concept.

- For advanced students: Develop your project with a pair of programming environments that handle sound and image separately. Some arts-engineering toolkits (like Max/MSP/Jitter, Pure Data, SuperCollider, and ChucK) excel at sound synthesis, while other development environments (like Processing, openFrameworks, Cinder, and Unity) have richer feature sets for graphics. Signals can be shared between the applications by means of a communications protocol like OSC or Syphon.

- Mapping performance gestures to your instrument's control parameters is perhaps the foremost design challenge of this assignment. Body movements that feel logically simple may produce hard-to-interpret sensor data; likewise, small changes to your instrument's control parameters may have nonlinear perceptual effects. Improve the intuitiveness of your instrument's mappings by incorporating a tool for real-time regression, such as Rebecca Fiebrink's Wekinator or Nick Gillian's Gesture Recognition Toolkit.

- Create an instrument that will only be used by one person. (This is at odds with commercial agendas and corporatized HCI education, in which the expectation is that design is something done for the widest range of users.)

Making It Meaningful

Good instruments offer inexhaustible possibilities for expression, composition, and collaboration. To a performer, the value of an instrument hinges on how well it supports the creative feedback loop known as “flow.” i An instrument that is responsive but crunchy can be more gratifying than a device that easily begets dazzling results. Hence, in this assignment, the emphasis is on the suppleness of an instrument's interaction design and the range of expression it makes possible (the performer's experience), rather than on the aesthetics of the audiovisuals it produces.

A “North Star” for instrument design is to create something “instantly knowable, yet infinitely masterable.” ii Consider the pencil, or the piano: its basic principles of operation are simple enough for a child to deduce, yet one can spend a lifetime using it and still find more to say; sophisticated expressions are possible, and mastery is elusive. From the standpoint of systems design, our challenge is that ease of learning and expressive range are antithetical design requirements: optimize for one, and the other suffers. In making an instrument for simultaneous sound and image, this challenge is compounded by another: expressive malleability in one modality often comes at the expense of rigidity in the other.

It is helpful to consider the typology of audiovisual systems and the design strategies they use. Sound visualization, for example, is a common feature in desktop music players, VJ software, and phonology tools. Principles of image sonification underpin film scores, game music, and some tools for the visually impaired. The term “visual music,” used by creators of some color organs and abstract films, can even refer to a strictly silent medium, one comprised solely of animated imagery with temporal structures that are analogous to musical ones. In the realm of computer-based performance systems, designers have used a variety of visual interface metaphors to control and represent sound. “Control panel” interfaces, for example, use knobs, sliders, buttons, and dials to govern synthesis parameters, evoking the look of vintage synthesizers. “Diagrammatic” interfaces, such as scores and timelines, use the graphical conventions of information visualization to organize representations of sound along axes like time and frequency. Others use “audiovisual objects,” wherein a performer stretches, manipulates, or knocks virtual objects together in order to trigger or modulate corresponding sounds. In “painterly interfaces,” gestural marks performed on a 2D surface conjure and influence a fine-grained aural material.

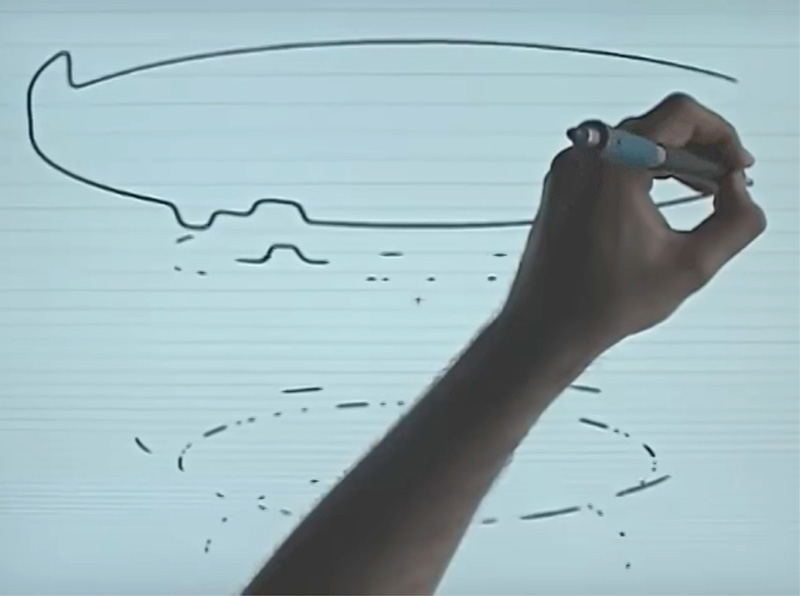

163. Amit Pitaru's Sonic Wire Sculptor (2003) is a tablet-based system for authoring looping scores. Melodies are represented by drawings that curl around a cylindrical 3D space.

164. Psychic Synth (2014) by Pia Van Gelder is a responsive audiovisual environment in which a participant's brainwaves are captured by an EEG headset, in order to establish an immersive biofeedback loop that governs video projection, colored light, and immersive sound.

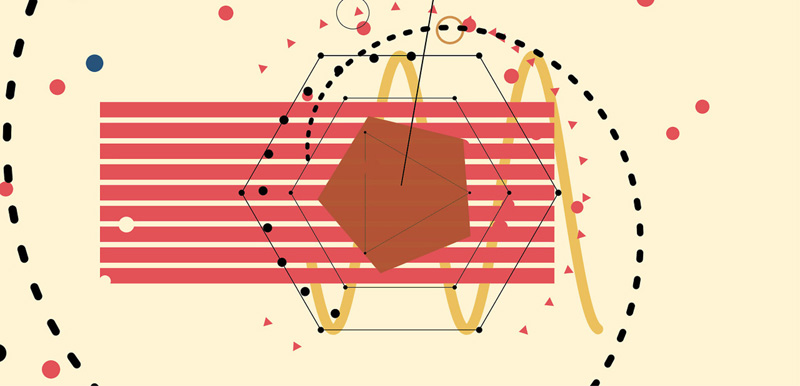

165. Patatap (2012) by Jono Brandel and Lullatone is a browser-based app for the simultaneous performance of sound and animated imagery. Each key on a standard computer keyboard triggers a unique noise and snappy animation.

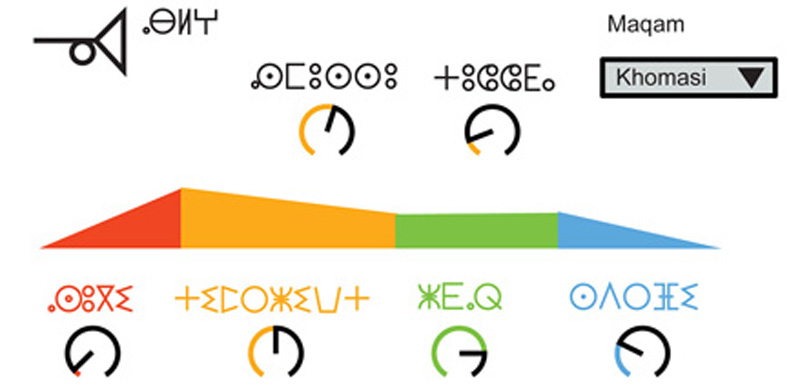

166. Jace Clayton's Sufi Plug Ins (2012) are a suite of seven free tools that extend the functionality of Ableton Live, a commercial music software sequencer. These software-as-art visual interfaces are designed to support non-Western conceptions of sound, such as North African maqam scales and quartertone tuning. The interface is written in the Berber language of Tamazight, using its neo-Tifinagh script.

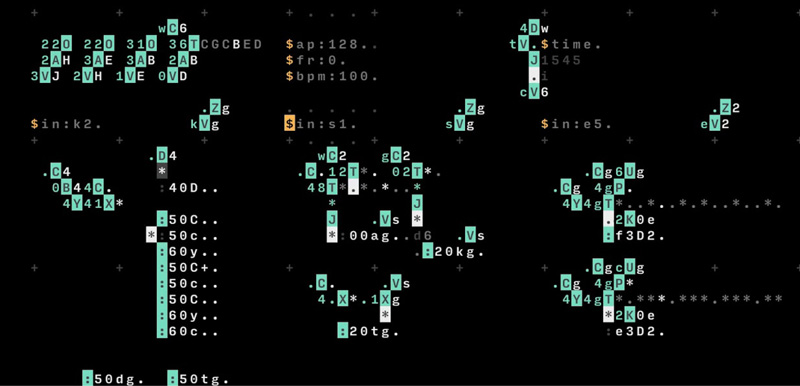

167. Orca (2018) by Hundred Rabbits is an esoteric programming language and live-coding interface for creating and performing procedural sound sequencers.

Additional Projects

- Louis-Bertrand Castel, Clavecin Oculaire (Ocular Harpsichord), 1725–1740, proposed mechanical audiovisual instrument.

- Alex Chen and Yotam Mann, Dot Piano, 2017, online musical instrument.

- Rebecca Fiebrink, Wekinator, 2009, machine learning software for building interactive systems.

- Google Creative Lab, Semi-Conductor, 2018, gesture-driven online virtual orchestra.

- Mary Elizabeth Hallock-Greenewalt, Sarabet, 1919–1926, mechanical audiovisual synthesizer.

- Imogen Heap et al., Mi.Mu Gloves, 2013–2014, gloves as gestural control interface.

- Toshio Iwai, Piano – As Image Media, 1995, interactive installation with grand piano and projection.

- Toshio Iwai and Maxis Software Inc., SimTunes, 1996, interactive audiovisual performance and composition game.

- Sergi Jordà et al., ReacTable, 2003–2009, software-based audiovisual instrument.

- Frederic Kastner, Pyrophone, 1873, flame-driven pipe organ.

- Erkki Kurenniemi, DIMI-O, 1971, electronic audio-visual synthesizer.

- Golan Levin and Zach Lieberman, The Manual Input Workstation, 2004, audiovisual performance with interactive software.

- Yotam Mann, Echo, 2014, musical puzzle game, website, and app.

- JT Nimoy, BallDroppings, 2003–2009, animated musical game for Chrome.

- Daphne Oram, Oramics Machine, 1962, photo-input synthesizer for “drawing sound.”

- Allison Parrish, New Interfaces for Textual Expression, 2008, series of textual interfaces.

- Gordon Pask and McKinnon Wood, Musicolour Machine, 1953–1957, performance system connecting audio input with colored lighting output.

- James Patten, Audiopad, 2002, software instrument for electronic music composition and performance.

- David Rokeby, Very Nervous System, 1982–1991, gesturally controlled software instrument using computer vision.

- Laurie Spiegel, VAMPIRE (Video and Music Program for Interactive Realtime Exploration/Experimentation), 1974–1979, software instrument for audiovisual composition.

- Iannis Xenakis, UPIC, 1977, graphics tablet input device for controlling sound.

Readings

- Adriano Abbado, “Perceptual Correspondences of Abstract Animation and Synthetic Sound,” Leonardo 21, no. 5 (1988): 3–5.

- Dieter Daniels et al., eds., See This Sound: Audiovisuology: A Reader (Cologne, Germany: Walther Koenig Books, 2015).

- Sylvie Duplaix et al., Sons et Lumieres: Une Histoire du Son dans L’art du XXe Siecle (Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou, Catalogues Du M.N.A.M., 2004).

- Michael Faulkner (D-FUSE), vj audio-visual art + vj culture (London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd., 2006).

- Mick Grierson, “Audiovisual Composition” (DPhil thesis, University of Kent, 2005).

- Thomas L. Hankins and Robert J. Silverman, Instruments and the Imagination (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995).

- Roger Johnson, Scores: An Anthology of New Music (New York: Schirmer/Macmillan, 1981).

- Golan Levin, “Audiovisual Software Art: A Partial History,” in See This Sound: Audiovisuology: A Reader, ed. Dieter Daniels et al. (Cologne, Germany: Walther Koenig Books, 2015).

- Luisa Pereira, “Making Your Own Musical Instruments with P5.js, Arduino, and WebMIDI,” Medium.com, October 23, 2018.

- Martin Pichlmair and Fares Kayali, “Levels of Sound: On the Principles of Interactivity in Music Video Games,” in Proceedings of the 2007 DiGRA International Conference: Situated Play, vol. 4 (2007): 424–430.

- Don Ritter, “Interactive Video as a Way of Life,” Musicworks 56 (Fall 1993): 48–54.

- Maurice Tuchman and Judi Freeman, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890–1985 (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986).

- John Whitney, Digital Harmony: On the Complementarity of Music and Visual Art (New York: Byte Books/McGraw-Hill, 1980).

- John Whitney, “Fifty Years of Composing Computer Music and Graphics: How Time's New Solid-State Tactability Has Challenged Audio Visual Perspectives,” Leonardo 24, no. 5 (1991): 597–599.