Summer 2012:

About nine months before graduation

ISAIAS SPENT THE SUMMER before his senior year working with Dennis and his parents on painting jobs, and in one house in Germantown, a well-to-do suburb, he used his cell phone to take a picture of himself in a mirror, then posted it on Facebook—his glasses off, a serious expression, his head haloed by light streaming from a window behind him, his shirt paint-spattered. After school started, he continued to do painting jobs on the weekends.

One day early in the school year, Isaias hurried to the vocational center near Kingsbury High to speak with Corey A. Davis, an instructor. Isaias sometimes ran from place to place, and he arrived sweating and tired, as if he’d just completed a race, Mr. Davis recalled. Isaias told him that he needed permission to sign up for the audio recording class. No problem—Mr. Davis agreed.

The class was optional, and Isaias wanted it badly. He’d sit behind an actual mixing board with knobs and sliders, learning to create songs and sound effects. He’d listen to NPR for ideas on how to edit radio stories. Every day, he would walk from the main high school building to the vocational center, and he’d stay there for about three hours, working contentedly.

But for many other Kingsbury students, the start of the school year would bring not contentment, but long hours of sitting in a gymnasium with nothing to do.

* * *

August 6, 2012, the first day of Isaias’ final year of high school, dawned with a clear blue sky. The electronic sign in front of Zion Temple Church of God in Christ sent drivers a message of hope in golden scrolling letters:

GOD BLESS OUR TEACHERS

GOD HELP OUR PARENTS

A mile or so away at Kingsbury High, blue police lights flashed and an officer blocked traffic to protect students as they walked from the residential neighborhood of brick homes, crossed North Graham Street and made their way onto the school grounds. A crowd of kids milled around outside, dressed in white uniform shirts. Girls squealed as they recognized friends. “You’re so gorgeous! You’re so gorgeous!” “Maria!” A father pulled a red pickup truck to a stop, accordion-heavy norteña music playing, and a child got out. A few feet away, in front of the school, Principal Carlos Fuller, a bald, strongly built man with coffee-colored skin, shouted at a student and gestured with a small two-way radio that let out bursts of static. He greeted a boy in a wheelchair. “You have a good summer?” he asked. “Yeaaah!” the boy replied with a big smile. Mr. Fuller sent one kid straight to the office for a violation of school uniform rules. He slapped hands with other boys. “Looking good, baby, looking good.”

Mr. Fuller walked into the school, passed a JROTC instructor running the metal detector check, strode into the front office and stepped to a microphone. His voice crackled over loudspeakers throughout the building. “¡Bienvenidos escolares y campeones! Welcome, scholars and champions! What’s up? This is going to be a great, great year!”

Mr. Fuller spoke only a little Spanish, but he made an effort, especially on the announcements. Several teachers spoke the language fluently. On this first day, Mr. Fuller talked about class schedules. “Some of your schedules may have holes. Some of you guys may not have schedules at all. Teachers, please look for your temporary schedules.”

He finished with a flourish: “That being said, at the school of scholars and champions, where every day it is the sole mission of every adult in this building that at a minimum, 90 percent of our children will be proficient on all of our assessments. At a minimum, 60 percent of our children will be advanced. All of our children strive to make 30s on the ACTs. ¡Que tenga un buen, buen día! This is going to be a great, great day, a great week, a great month, a great year! Thank you.”

On nearly every other day that followed, Mr. Fuller attacked the morning announcements with similar enthusiasm. In a nod to the small number of students from the Middle East, he’d often start with the Arabic phrase “sabahu alkhayr,” or good morning. He would clasp and unclasp his hands, opening and closing his eyes. Sometimes he’d abbreviate the last part about test scores and say, “Where every day is 90-60-30!” He’d offer life lessons: “Please surround yourselves with positive people! Every decision you make will have a positive or negative consequence. Whether it is positive or negative depends on you.” He’d occasionally mix in ACT vocabulary words like “zephyr” and “yen.” Even when he was having a bad day, he tried to bring excitement and energy.

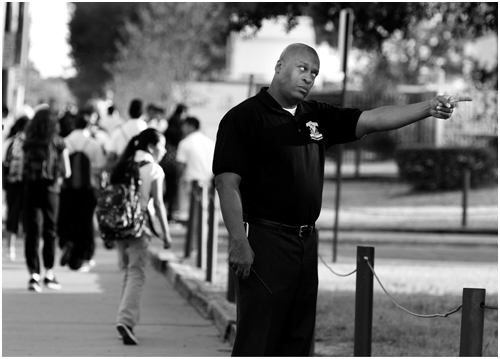

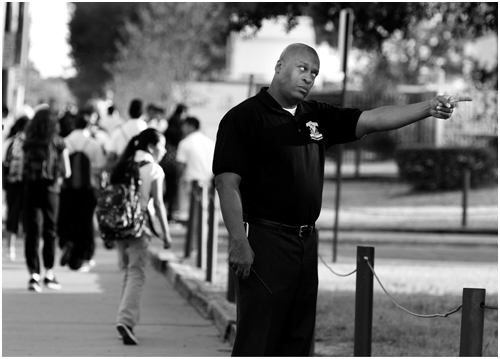

Mr. Fuller admonishes a student early in the school year. (Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

Mr. Fuller made his morning announcements shortly after 7:30 a.m., but school wasn’t close to really starting. The messy process of registration continued, and guidance counselors were still scrambling to put together class schedules.

Students killed time in homerooms throughout the building as a multiethnic line of parents and teens formed in the front office and stretched into the hall. A white man consulted a cell phone, a little Hispanic girl in pink with a pacifier played inside the office, an Asian father accompanied a teenaged son, and a black teenaged boy waited with his mother and two little boys. Following the announcement, dozens of other students and their families filled out registration forms in the school library, though registration had officially taken place the previous week.

Nearly two hours passed before an assistant principal made an announcement: students who had registered but did not have a schedule should receive a temporary schedule. “All other students that are not registered need to report to the gym.” In the gym, students without schedules would wait in limbo. No one could say for how long.

Dozens of students walked into the hallways, past the rows of lockers and under the colorful flags of the world. Metal doors clanked open as students left the main building and walked into the midmorning heat and the buzzing drone of cicadas. They made their way to the gym, where a similar buzz sounded from one of the old lamps overhead.

Only a handful of students came in at first. Then four more girls arrived. Then more. A boy said, “I’m so glad we got here before everybody else did.” The trickle became a torrent. The kids climbed up the metal steps and took seats on the maroon bleachers. By the end of the day, I counted 175 students in the gym. The good news was that they had come to school at all. Students routinely skipped school at Kingsbury, particularly on the days that everyone agreed were pointless. Given the severity of this year’s scheduling problems, there were many pointless days to come.

In the school gym that first week, the kids whiled away the hours talking, sleeping, eating, lounging and playing with cell phones. One Filipino boy simply sat and stared into the distance, day after day. On Wednesday morning, the third day of school, a river of teenagers in white uniform shirts flowed back to the gym. Only one door was open, and a crowd quickly formed at the narrow entrance like water behind a dam. A tall, muscular young white teacher named Lucas Isley directed the students to points on the bleachers. “If we have a homeroom, down there. No homeroom, no schedule, right here.”

This gym adjoined a smaller exercise space that Kingsbury Middle School used. On the other side of a partial barrier, younger kids killed time in a different way: walking in slow circles.

One of the 200 or so students sitting in the high school gym that day was Franklin Paz Arita, a lanky 16-year-old with large brown eyes, curly hair, an open face and a frequent smile. He was born in Honduras and smuggled into the United States as a child. His mother had endured an abusive relationship in California with a man who once threatened to kill her with a sledgehammer. Franklin said years later that he remembered the details vividly: how the man had raised up the weapon and said he’d smash her with it. Franklin was so young that he hid behind his mother, who was holding his baby sister. “My older brother basically had to talk him out of it,” Franklin recalled. Meanwhile, an older sister slipped away and called the police. “And since he was drunk, a few moments later he passed out,” Franklin said. “And by the time he was up again, the cops were already there.”

When Franklin’s mother left this man, she and her children moved from place to place before settling in Memphis. Now she cleaned houses and was raising Franklin and his two younger siblings on her own.

Two things motivated Franklin: his faith in God and his love for his mother. He liked math and science and wanted to become a detective or forensic investigator. He played soccer and tried to make money by selling sets of kitchen knives door to door. In the gym, though, he was bored and hot and wasting time.

On the first day of school, Franklin had arrived carrying a green notebook. By Wednesday, he had taken exactly half a page of notes, from when he’d sat in on an English class. He felt cheated—he’d been assigned classes that he had already taken or that he didn’t need even though he’d signed up for classes before leaving school in the spring. Though hundreds of students sat in the gym, Franklin knew that many other Kingsbury students had class schedules and were already learning. It wasn’t fair.

One of the teachers watching the gym, Mr. Isley, was a 26-year-old from Michigan who had gone through training with Memphis Teaching Fellows, a program for new educators. He had read a book called Teach Like a Champion, which told him that a teacher who found efficient ways to handle classroom chores like passing out papers could save 30 seconds per class period. At six periods a day, that added up to three minutes. Over the course of a school year, nine hours. At 1:00 p.m. on Wednesday, he calculated that the kids had sat there for between 18 and 20 hours. He didn’t like it.

When the end-of-day announcements finally came on Friday afternoon, I counted 227 kids still in the gym—roughly a fifth of Kingsbury’s student body. Their chatter drowned out the afternoon announcements and dismissal. Franklin left, eating a bag of crispy snack fries and planning to set up knife sales demonstrations. He carried the same green notebook as on Monday. In five days of school, he had still taken only the half page of notes. Three percent of the 180-day school year had passed. He’d start school next week.

The number of students in the gym gradually dropped until August 17, the tenth day of the school year, when Mr. Fuller walked into the guidance office and announced, “That’s the last of the group! Gym is clear!”

Several factors contributed to the scheduling chaos, including students coming to school days late. But one of the primary issues was a computer problem.

Guidance counselors Tamara Bradshaw and Brooke Loeffler said many of the students who showed up at Kingsbury that August had mistakenly been assigned to another school, Douglass High. The computer records system would not allow the same student to enroll in two different schools. Until staffers at Douglass High formally dropped those students from their school’s roster, the computer system wouldn’t allow Kingsbury guidance counselors to build a schedule for them. During those first few weeks, schools called one another or faxed back and forth lists of students to drop.1

The problems that school year went far beyond Kingsbury. On September 11, dozens of students demonstrated outside another Memphis City School, Carver High, to draw attention to cuts to band and choir programs, lack of air conditioning in sweltering classrooms, and scheduling problems. Seventeen-year-old protest leader Romero Malone told the local newspaper that the chaos affected almost all the students in the school. “Ninth graders had nothing on their schedule but lunch,” he said. “It lasted two to three weeks. They made the students go to a classroom where they were watched over while administrators tried to do schedules.”2

Similar problems had cropped up elsewhere, notably in Los Angeles, where thousands of students throughout the city’s public system had to deal with incomplete or inaccurate schedules in 2014, the Los Angeles Times reported. At that city’s Jefferson High School, scheduling problems got so bad that a judge ordered education officials to fix them immediately.3

When I spoke with Mr. Fuller a full month after the start of the school year, he described the technical problems and also said he wasn’t happy with how the guidance staff had handled scheduling. (My sense was that the guidance staff wasn’t happy with how Mr. Fuller had handled it either.) Either way, he acknowledged it was a mess. “It was a headache. We’re still in the process of cleaning up some schedules, which we have to do every year anyway, but we have to do it so much later because we didn’t take care of it on the front end.”

Registration the following year, August 2013, was far smoother, and Mr. Fuller offered an explanation: the district had expanded the length of time that the guidance counselors worked from 10 months to 11 months, which allowed them to come into school earlier and start working on the schedules.

The problems at the start of Isaias’ senior year clearly hurt the students’ morale and motivation. I talked with two boys who’d sat in the gym for days. They were mumbly and sullen, and I couldn’t blame them. What was their impression of Kingsbury? “That this school boring,” one boy said.

Seventeen-year-old Faith Nycole Nostrud went weeks without a real schedule, and her dad said she compounded her problems by not going to school. “If I’m going to be at school, I want to do something,” she said. “It frustrates me to come to class and then just sit there the whole hour. It’s like, ‘Well, I could be doing this at home.’” In October, she transferred to Gateway, a private Christian school that served as a backup for many kids in the neighborhood.

English teacher Philip Tuminaro had once spent the first days of the school year trying to teach. But an ever-changing roster of students made it clear that he had to keep re-teaching the same material. So now he spent the first chaotic days of each school year reviewing material that all the students would need: preparation for the ACT test. He recognized a vicious cycle: teachers didn’t teach, so students didn’t come. Given the circumstances, he wouldn’t come either, and he didn’t know whom to blame.

Setting aside the question of blame for a moment, the organizational problems in places like Memphis and Los Angeles reflected a broader social inequality. In the 1990s, I went to the city’s best public high school, White Station, and I got my schedule on the first day and went to class immediately. If I had endured weeks of chaos at the start of each year, my parents would have sent me elsewhere. Most adults with educational savvy, money and options would do the same. But many Kingsbury parents didn’t have these things. Most didn’t complain or pull their kids out of school.

* * *

Isaias escaped the worst of the scheduling chaos, although for some reason he spent a few weeks in precalculus, a class he didn’t need. The previous year, as an eleventh grader, Isaias had taken the school’s highest math course, Advanced Placement Calculus AB. He had also taken a college-level finite mathematics class and made a B. In precalculus, the teacher let him study for his other classes. Sometimes he coached other students like an assistant teacher.

Isaias eventually got his schedule changed to drop precalculus and take piano, where he practiced in a room full of expensive-looking computer screens and keyboards. That was one of the contrasts of Kingsbury—despite its high poverty rate and organizational problems, many of the classrooms were equipped with new technology, like SMART Board interactive screens.

At lunchtime on the first day of school, the students had streamed out of the main building, into the sweltering heat, up some steps and into the air-conditioned cool of the cafeteria, a space that smelled of nachos.

“I’m so proud of you! Here! Monday!” said Margot Aleman, smiling as she greeted a student just inside the cafeteria door. Margot worked for an outside evangelical Christian organization called Streets Ministries. She came to Kingsbury as a volunteer and was a constant presence in the school. She was in her thirties and often wore multicolored blouses. She continued her greetings. “Welcome to high school, baby! We’re proud of you.” A tall, muscular white football player with blue eyes and a big smile limped in on crutches. “Cody! Again, sweetie?” Margot said.4

Now the kids surged up the stairs about five or six abreast. Some Hispanic boys wore rosaries over their white uniform shirts. One wore a necklace with an image of the Virgin Mary in what looked like a tiny frame.

Some of the kids made good money working in construction. Margot pointed out a Hispanic boy at one of the round cafeteria tables who was holding hands with a younger white girl. “Him being here the first day of school, it’s a lot. He made $600, $700 a week,” Margot said. Another student she knew worked a night shift from 10:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. “At least he came to school. That’s a good thing.” She pointed out a bubbly ninth grader. “I got to take care of her ’cause she’s cute. Guys are going to be all over her.”

The kids ate in shifts, and the second group arrived shortly before noon. Again, Margot stood in the doorway, hugging students and keeping up her greetings, switching between Spanish and English. “My baby, Tri!” “How are you, Mr. Freshman?” “You are not going to skip.”

As the students settled down to eat, Margot and I left the cafeteria. We walked the short distance to North Graham Street, turned to the right and continued past Kingsbury Middle School, past a church, and arrived at the Streets Ministries community center.

In 1993, The New York Times profiled the founder of Streets Ministries, a 35-year-old blond, bearded white man named Ken Bennett who drove an old Ford van to the city’s worst housing projects and worked to bring tutoring, mentoring and love to poor kids, almost all of them black. He had married a teacher, fathered a baby daughter, and had already recruited a network of volunteer tutors.

“My faith calls me to do this, not in a romantic or martyrdom way,” he said at the time. “We have two cars and a house. We don’t go without. We are about spreading the Gospel of Jesus Christ, but we’re not conditional.” Kids could take the Gospel or leave it, he said. “We’ll continue to track with them.”5 In the nearly 20 years since then, Streets had grown dramatically and now ran two multimillion-dollar community centers, one in downtown Memphis and a new one near Kingsbury High that opened in 2011. The building was equipped with spacious basketball courts, classrooms, a computer lab, an activity space for special programs and a room for nonviolent video games. Now Margot found an empty room and unpacked a toasted sandwich of tuna mixed with corn kernels—not a traditional meal, just how she liked her tuna.

She said Streets focused on the “Three E’s”: to engage in relationships with kids and faculty, to educate and to evangelize. But she said she rarely talked about God outside of specific events at the community center unless the students asked. “I’m not gonna pull out the Bible and start preaching to the kids,” she said. “I’ll lose them. But I will share my love and the reason why I’m still alive, because of God. Basically all of us do.” Unlike most staffers at Streets, she did not have a bachelor’s degree. “And I’m not very bright, but I can help them.”

On the surface, Margot seemed all sunshine, love and cheer. But growing up in the town of Weslaco in South Texas near the Mexican border, she had lived through dark events. She said that at six, a relative raped her. At 12, someone else sexually abused her. At 13, she met her biological father for the first time. He told her three things: One, no one knows you exist. Two, your mother and I did not plan you. Three, your mother was my mistress. Margot developed suicidal thoughts as a teenager and became a “cutter,” a person who inflicts wounds on herself.

When she was 17, a pastor molested her. She became a youth minister in her early twenties but around age 28 she became addicted to pills, became suicidal again and started having panic attacks. Then one day, she surrendered everything to God—again.

Margot sometimes shared her story with kids. Often they told her they had been abused, too, and sometimes they’d tell her other secrets: about a pregnancy scare, an alcoholic mother, or a dead mother and a vanished father.

She came to Memphis when the Streets founder asked a local pastor and Spanish-language radio personality named Gregorio Diaz to help him locate a Hispanic person with legal documents and experience working with youth. Mr. Diaz recommended Margot, who had also worked in Christian radio. Now she worked 50 to 60 hours per week. “We don’t care. This is not work for us,” she said. “This is playground. I mean, seriously: Who gets paid to take a kid out to a movie?”

She would turn 38 in a few days and said she’d found peace without a nice car, a big house, a husband, or children of her own. “I love teens. They’re drama, they’re crazy and they’re knuckleheads, but they’re great. I love them. They’re my babies.”

Though Margot worked for an outside agency, she played a role much like that of a guidance counselor. Kingsbury students also had counseling help from Patricia Henderson, who worked for TRIO, a federally backed program designed to help low-income students get to college. Later in the school year, the social services agency Latino Memphis used funds from the Lumina Foundation to launch a mentoring program at Kingsbury called Abriendo Puertas, or Opening Doors.

The outside staffers supplemented the four overworked guidance counselors on the school’s payroll. The staff counselors not only assisted students with college applications, but administered standardized tests, set course schedules, and even sold prom tickets. Counselor Brooke Loeffler acknowledged that she didn’t have enough time for the relationship building that makes a difference in kids’ lives, and she regretted it. “We’re doing clerical work and administrative work,” she had said early in the school year. “We don’t have time to sit down and have personal conversations.”

Many other schools in America had fewer counselors than Kingsbury because when school systems cut budgets, guidance counselors were vulnerable. In California, the state’s largest school systems lost hundreds of counselors to layoffs and attrition after the 2007–2008 financial crisis, making their ranks so thin that “most students will be hard pressed to get the personal attention they need, whether for academic or mental health reasons,” the California organization EdSource wrote in 2013.6

In the years that followed, some California districts began to hire counselors again, a good thing, because low numbers of counselors likely meant some students wouldn’t go to college. Researchers with the College Board concluded that adding an additional guidance counselor to a school staff—boosting the number from one to two, for instance—resulted in a 10 percent increase in the number of students enrolling in four-year schools.7

Some might worry that an evangelical Christian organization had involved itself so deeply in a secular, government-funded school. But that was like complaining that Catholic Relief Services or the Muslim Red Crescent had delivered food to survivors of an earthquake. Kids at Kingsbury needed adult guidance.

* * *

Another adult who interacted frequently with Kingsbury students was Eduardo Saggiante, the school’s full-time Spanish interpreter, a 38-year-old former professional soccer player from Mexico with a gentle demeanor and a tired face. In the early days of school, he was busy.

Each line of the school registration forms gave instructions in both English and Spanish, but the papers intimidated one Mexican mother. She handed Eduardo the pen. You do it. He asked for her name, address, and countless other details and filled out her paperwork line by line. She’d only made it as far as the fourth grade.

On the second day of school, he helped orient a 15-year-old girl recently arrived from Cuba. “Ese va a ser tu homeroom,” he told her. This will be your homeroom. “El locker es esto.” This is a locker. He tapped one. Clang clang. He’d repeat this process for days after the school year started, as students still drifted in.

Sometimes, before making a difficult call to a parent, he’d pause in the teacher’s lounge to psych himself up for the moment. His wife said he took his job too personally. He couldn’t help it. He’d studied economics in Mexico, not counseling. He didn’t know how to deal with gangs. Yet here he had to do that and much more. He helped rescue a boy from a father who beat him. He spied on the houses that harbored kids who’d sneaked away from school to party. When girls disappeared, he’d play the role of detective, talking with the police and scouring Facebook pages. Often the girls had run off with boyfriends. One time he told a mother that no, it’s not okay for a 15-year-old girl to go live with a 20-year-old man. About six girls would go missing that year. He lost count. They all turned up eventually.

* * *

During the chaotic first days of the academic year, the administrators had a hard time keeping track of who was in the school. By October, the guidance office could confirm the stats: 422 Hispanic students made up 37 percent of the total school population of 1,143. African or African-American students made up 43 percent of the total. Whites made up 15 percent, Asians 3 percent and a small number of others were classified as American Indian or their race wasn’t listed.

In the course of the year, I’d meet children of immigrants not just from Mexico, but from far-flung places including Cambodia, Iraqi Kurdistan and Ivory Coast. Many teachers also came from other states or from abroad. Tomfei Teuo-Teuo came from Togo in west Africa, taught French and also spoke fluent German. Math teacher Mamadou Diong came from Mauritania in northwest Africa; each side of his face was marked with a roughly tear-shaped scar, not far from the eye. Such decorative scarring was a custom in his part of the world.

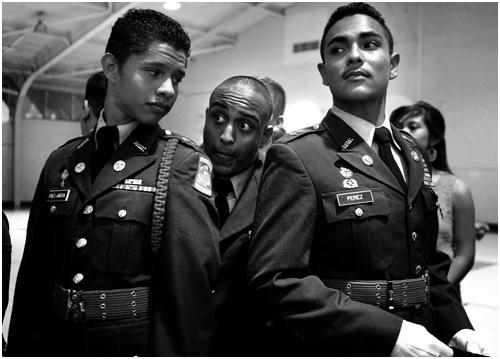

On the sixth day of the school year, students still came to the guidance office to change schedules. Some hung around because their classes hadn’t started and they had nothing better to do. Jose Perez flipped through a military recruiting magazine and pointed out a picture of a Hispanic warrior to another student. Later, Tommy Nguyen asked Jose what branch of the military interested him most. Jose’s answer was certain. “I’m going to do Marines.”

Of the four branches of the U.S. military, the Marines were smallest and enjoyed a reputation for elite toughness. Jose longed to become one of them.

Jose served as the highest-ranking student leader in Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps, or JROTC. His formal title was Battalion Commander—and at Kingsbury, that meant something. Far more than in most schools, the JROTC cadets in their crisp olive-green dress uniforms defined the culture of Kingsbury. For years, the school had steered almost all freshmen into the JROTC program in what Mr. Fuller described as an effort to encourage leadership skills and discipline. They did military-style exercises like shooting air rifles, and adult instructors also taught other subjects including U.S. government and personal finance. Students who showed potential could earn ranks and lead other students in activities such as precision marching and drills.8

The military and the school system each paid half of the adult instructors’ salaries. At the start of Isaias’ junior year in the fall of 2011, school system budget cuts reduced the number of Kingsbury JROTC instructors from four to two, and the number of students enrolled dropped from around 400 to around 160. Still, the JROTC program remained visible at most school assemblies and special events as students in uniform carried out flag ceremonies. The program had a roughly even split between boys and girls. When Congressman Steve Cohen visited Kingsbury later in the year, a tall JROTC student named Dante Bonilla escorted him through the school. And retired army master sergeant Ricky Williams cut an imposing figure as he stood at the school door in the morning and ordered students to tuck their shirts in.

Sergeant Williams said he wanted to motivate young people to lead productive lives after high school, and that recruiting them for military careers wasn’t the point of JROTC. Still, military recruitment and JROTC often went hand in hand. In his junior year, Jose Perez contacted a Marine recruiter who came to the high school and talked with him.

Franklin Paz Arita (left) and Jose Perez (right). The student in the center is Astawusegne Desalegne, better known as Ismail. (Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

Jose had been born in Mexico and brought to the country illegally as an infant. At the end of the conversation, Jose told the Marine that he didn’t have a Social Security number, but he was working on it. The Marine said he couldn’t help Jose until he took care of that.

Now Jose simply had to get the document.

That morning, counselor Tamara Bradshaw grew tired of Jose hanging around the guidance office. “Jose, go to class.”

“We’re in class?” Jose asked.

“We’re in homeroom,” Tommy Nguyen interjected.

“Homeroom’s a class,” the counselor said.

It was 9:21 a.m. School had been in session for nearly two hours, and little had happened.

The guidance counselors had asked Mariana Hernandez and Adam Truong to put course-change forms in alphabetical order. Now these reliable seniors had finished the task and sat at a table in the guidance office waiting for something else to do.

“What if we’re in here ’til lunch?” Adam asked. More time passed. Mariana said, “We should see if they need anything.” So she and the others started walking around the school, asking adults if they needed help.

Mariana was a slender, pretty girl who wore stylish dark-rimmed glasses and ranked among the top ten students in the senior class. She was born in Mexico; her parents brought her to the United States when she was five, and then her immigration visa expired.

She had once thought that being Hispanic and undocumented would bring bad consequences. Now, she had only a couple of Hispanic friends. Most of her friends were Asian, like her boyfriend Adam and their friend Tommy, both of whom came from Vietnamese families.

She spent a lot of time with Adam, who swam and lifted weights and liked to listen to country music and rap, especially older artists like Tupac Shakur. Mariana’s parents liked Adam, and he often visited their house.

Adam Truong and Mariana Hernandez. (Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

Later in the year, Mariana worked in a school computer lab to fill out an application for a community college. In the box for ethnicity she marked “Hispanic.” Like the U.S. Census, this form considered Hispanic ethnicity separately from race, and the computer screen wouldn’t let her continue unless she also marked one of the race categories—African-American, white, et cetera. She didn’t know what to do.

Beside her, Adam said, “Put Asian.” So she did.

Some Mexican immigrant parents largely let their children handle school and college decisions on their own. By contrast, Mariana’s parents paid close attention to her schoolwork and pushed her hard.

“You know how they make the stereotyped comments about the Asian parents being the most demanding?” she told me in June before the school year started. “Well, if my parents had to fall under some category, that would be them.”

Her father had finished twelfth grade in Mexico with a technical diploma, her mother the ninth grade. They had met in Guadalajara, one of Mexico’s largest cities, and were now in their forties. Her parents both worked for a company that ran a chain of franchise restaurants, her father in the in-house construction department, her mother in one of the restaurants. Like Isaias’ parents, they didn’t speak much English, and I spoke with them in Spanish. “I tell Mariana that I can’t give her an inheritance,” said her mother, Adriana Armas. “But studying will give her what an inheritance would.” She didn’t want to see Mariana killing herself at work like her parents did.

Adam sometimes felt afraid of Mariana’s father, Ricardo Hernandez, who was bald and often wore a severe expression. Yet his true nature was gentle, and he fully supported his daughter’s education. “It would really make me sad if she can’t go to the university,” he said. He believed that a university degree would always help a person find a job. True, you heard stories of people who had graduated from college and worked as cashiers, he said, but even if people weren’t using their educations at the moment, they could figure out a way to do so.

Mariana had scored a 19 on the ACT test, decent for Kingsbury but below the national average of 21, and her parents were upset. “They just said it was disappointing,” she said. “I shouldn’t be everybody else. I have to be above standards.” (She eventually pulled up her score to 21.)

She signed up for all the available enrichment activities, including a Streets Ministries summer program that prepared students for college. Participants read books like The Hunger Games, Lord of the Flies and the Book of Romans from the Bible.9 They studied for the ACT on the campus of the University of Memphis. In the last week of the summer institute, Mariana spent several days at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and stayed overnight in a dorm.

She signed up for hard courses like AP Chemistry, where she’d prepare for a difficult national exam. Teacher Jihad Haidar gave the students extremely tough questions, and she doubted herself. “I guess we all know we’re not gonna pass this AP exam!” she said in class one day later in August. She said she found her family’s expectations overwhelming.

“Because what if one day I decide to be stupid and reckless like any other teenager and I screw it up? The way that my family members view me is no longer the way that they thought I was. So everything changes completely.”

And she worried about her immigration status. What if she finished high school, graduated from college and then went out into the job market and couldn’t find work because she didn’t have a Social Security number?

People like her who had been brought into the country illegally or on visas that expired often had no hope of ever gaining legal status. They lived for years in a legal gray zone.

Adults without papers lived the same way. Isaias’ father Mario told the story of the time he was driving with Cristina and they saw a police checkpoint. They couldn’t turn around. This was it. Immigration enforcement. Mario turned to Cristina and said, “I’ll see you back in Mexico.”

They had thought about the possibility of deportation. Since they spent so much time painting houses together, they imagined the agents might grab both of them at once, and their children might be left behind at school. At one point, they made an emergency plan with Paulina and other friends: in case of deportation, the boys would stay with the friends, who would arrange to send the children back to Mexico.

Now Mario and Cristina pulled up to the officers. It was only a seatbelt check. Someone handed them a brochure and sent them on their way.

It turned out that the government generally wasn’t trying to catch people like Mario and Cristina. Large businesses with powerful friends didn’t want agents to arrest and deport their workers. In 1998, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) launched Operation Southern Denial, raiding Georgia fields where owners used large numbers of unauthorized immigrant workers from Mexico to grow and harvest sweet Vidalia onions. The raids made workers flee, and the onion growers complained loudly to members of Congress that their multimillion-dollar crop would rot. The feds agreed to stop the raids and give the growers temporary amnesty until the harvest came in. INS official Bart Szafnicki helped broker the deal. “I’ve been in this 22 years and I have never done anything like this,” he told The Chicago Tribune. “It is absolutely unprecedented and it is very unlikely to ever happen again.”10

But it did happen again. In 1998 and 1999, the INS launched Operation Vanguard, an effort to reduce widespread hiring of unauthorized immigrants in the meatpacking industry in Nebraska and other Midwestern states. Instead of conducting raids, the government subpoenaed the Social Security numbers and other identification that workers had presented when they applied for the slaughterhouse jobs. In theory, the law banned employers from knowingly hiring unauthorized immigrants. But the immigrants often gave them fake documents, and an employer had no obligation to investigate carefully. In Operation Vanguard, officials told workers with suspicious paperwork to come to interviews and explain themselves. Thousands quit rather than face the agents.

Again, leaders of a powerful industry complained about the enforcement. Again, lawmakers took their side. Again, the government suspended the program.11

Even before Operation Vanguard had run its course, the INS had decided to deemphasize worksite enforcement. A March 1999 memo made deportations of criminal immigrants the top interior enforcement priority. Worksite enforcement became the lowest of five priorities. “In a booming economy running short of labor, hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants are increasingly tolerated in the nation’s workplaces,” The New York Times reported in 2000.12 The newspaper described stepped-up border enforcement and prosecutions of companies that smuggled in unauthorized immigrants or blatantly recruited them. “But once inside the country, illegal immigrants are now largely left alone. Even when these people are discovered, arrests for the purpose of deportation are much less frequent.” Such arrests had already dropped from 22,000 two years earlier to 8,600.

For people like Mario and Cristina, the chance of being pulled off a job site and deported would soon drop to almost nothing.

In a 12-month period around the time the Ramos family arrived, immigration officials arrested only 845 people on worksites nationwide. The federal government brought only a tiny number of “notices of intent to fine” against businesses for immigration violations: three, to be precise, in all of the United States.13

Across the country, local police generally couldn’t enforce immigration law. After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the INS was broken up into different agencies. The new federal agency in charge of catching unauthorized immigrants was called Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

In much of the United States, ICE had little manpower. When I was working in Arkansas in 2006, an ICE staffer named Rod Reyes told me the agency had about 16 agents in the entire state, fewer than the 21 sworn police officers on the streets in the small town of Hope. And ICE didn’t just handle immigration enforcement, it also pursued crimes such as terrorism and child pornography. Handling the deportation of a single unauthorized immigrant could take hours of an agent’s time, said Mr. Reyes, who was the resident agent in charge for ICE in Fort Smith, Arkansas. “People think that we can just pick them up and turn around and put them in a bus and ask them to leave,” he said. “And it doesn’t happen that way.”14

Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey argued that many modern immigration problems could be traced to a 1986 law called the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which, he said, had disrupted a smooth-functioning system in which Mexican men crossed the border illegally, worked, and went home. The law sought to curb future illegal immigration by expanding the Border Patrol and punishing employers who hired unauthorized immigrants. At the same time, it offered amnesty to large numbers of people who had entered illegally or overstayed visas.

Massey and his colleagues wrote that the law’s combination of amnesty plus new restrictions reflected the two competing interests in the nation’s immigration policy: businesses that wanted immigrant labor versus a public fearful of immigration and politicians who sought to win votes by exploiting that fear.

The problems with IRCA quickly became apparent. The 1986 law led to a black market for fake documents like the ones the immigrants were showing to get jobs at the Midwestern meatpacking plants targeted by Operation Vanguard. The 1986 law meant more risk and more paperwork for companies, and employers often responded by paying lower wages as a sort of compensation for their trouble. Some also sought to avoid the risk of sanctions by hiring through subcontractors who would take the blame if the government caught unauthorized workers on a job site. Soon, anyone who wanted a job in agriculture or construction might have to take a low-wage position or go through a subcontractor. That hurt everyone in the industry: all immigrants, regardless of legal status, and citizens, too, Massey wrote. And tighter border enforcement encouraged Mexican migrants to settle permanently in the United States. Demand for the labor of Mexican migrants continued. “If there is one constant in U.S. border policy, it is hypocrisy,” he wrote. “Throughout the twentieth century the United States has arranged to import Mexican workers while pretending not to do so.”15

People like legal scholar Eric Posner spoke of the “illegal immigration system”—an informal set of rules that allowed people like the Ramos family to live and work in America, but with limited rights.16

An old debate raged: Were immigrants doing jobs that Americans didn’t want? Or were they doing jobs Americans wouldn’t do at that wage and under those working conditions? My best guess is that both assertions are true to some degree, though I’ll leave it for others to debate. I’m more certain of this: at its heart, the illegal immigration system exploits its workers and aims to give them as little as possible.

Justice Brennan’s opinion in the 1982 school case Plyler v. Doe had shown a sophisticated understanding of how the desire for low-cost labor drove the system: “Sheer incapability or lax enforcement of the laws barring entry into this country, coupled with the failure to establish an effective bar to the employment of undocumented aliens, has resulted in the creation of a substantial ‘shadow population’ of illegal migrants—numbering in the millions—within our borders. This situation raises the specter of a permanent caste of undocumented resident aliens, encouraged by some to remain here as a source of cheap labor, but nevertheless denied the benefits that our society makes available to citizens and lawful residents.”

Decades later, the specter of a permanent caste of people with limited rights was closer to becoming a reality.

Immigration enforcement statistics spiked occasionally, but in general, the government had made a quiet deal with people like the Ramos family: Do your work, avoid trouble, and you can stay. Just don’t ask for too much—certainly not a trip home, or citizenship, or the right to vote. If your kids don’t have papers—as Dennis and Isaias didn’t—they can go to school through grade 12.

What would happen to them after that? And what would happen to children born in America, like Dustin? The leaders in the federal government didn’t think that far ahead. The feds left it up to states, local governments, and school boards in much of the country to figure out how to educate a huge wave of children of immigrants. Doris Meissner, head of the former Immigration and Naturalization Service in the Bill Clinton administration, told me in 2012 that she couldn’t recall any discussion among federal officials of what would happen to immigrants’ children.

Young people with unauthorized immigration status, like Mariana and Isaias, were becoming an especially high-profile group. Efforts to pass a bill to regularize their status, called the Dream Act, had failed in Congress. Some young protesters called themselves Dreamers and publicly pressured the president to do more to help them. Among them were Memphis residents Patricio Gonzalez and Jose Salazar who, along with others in 2012, re-created the civil rights era march of James Meredith from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi.

Just a few days after I spoke with Mariana in June 2012, President Obama made an announcement. His administration would grant limited immigration relief to young people without the approval of Congress. Those who met certain criteria would receive a two-year renewable work permit.

“Now let’s be clear: this is not an amnesty,” the president said at the time. “This is not a path to citizenship. It is not a permanent fix.”

Obama’s administration called the program Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. It was the biggest immigration legalization program since the 1980s.

Mariana, Isaias and many other Kingsbury students applied quickly. So did Dennis. The process required them to gather a wide range of records from the school system and other agencies. The families of Mariana and Isaias were among many that hired attorneys to help. Dennis and Isaias each paid a lawyer $1,000 to complete their applications, plus a fee of $465 each to the government. That fall, they traveled to the local immigration office, where they were fingerprinted and photographed. Then they waited.

* * *

On that slow day early in the school year, an administrator finally found a job for Mariana, Adam and Tommy. He brought them into the library and showed them how to cut out and laminate the numbers for the “Fight Free” board. The board posted a public count of how long each of the grade levels had gone without brawling. If the sophomores racked up enough “fight free” days, for instance, they’d win an award—maybe pizza or ice cream, or a chance to come to school out of uniform.

The three students busily went to work, cutting out numbers that ranged from zero to more than 50. Fistfights—most of them minor—broke out frequently enough among both girls and boys that the fight-free streaks that year wouldn’t last very long.

Mariana often helped out adults, as she was doing now, but she could show a rebellious streak, too. For a while, she assisted Mr. Fuller with the morning announcements in the front office, reading some items over the loudspeakers in both English and Spanish before the principal started his energetic “Good morning, scholars and champions!” ritual.

One morning later in the year, Mariana came to the front office to do the announcements. She was eating an apple, and with the microphone off, the principal told her not to—he’d later say the food attracted vermin. But Mariana argued with him. “Go down to the discipline office,” Mr. Fuller said. Mariana moved toward the door. On the way, in front of the principal, she took one more defiant bite.

For Mr. Fuller, this was unacceptable. “She’s in the front office doing what’s like a leadership role, and then gonna tell me, ‘What’s wrong with eating an apple in the building?’” Mr. Fuller said later. “So I had to remind her also, ‘Baby, you’re still a child in here, sweetie.”

Why didn’t she stop? “Because I was going to tell him that I needed it,” Mariana said. “My blood sugar was low. I’m not going to pass out in the main office and cause more dilemma.”

She ended up with an “overnight suspension,” a punishment that was largely a formality. Her parents weren’t upset. But Mariana wasn’t eager to come back and help Mr. Fuller again. “I hold a lot of grudges,” she said. And for the rest of that year, she would rarely do the announcements.

Now, though, Mariana and the others worked away. Tommy sat on the floor with a paper cutter and chopped up sheets of numbers, producing multicolored ribbons of scrap. “What if we go straight to sixth period?” Adam asked. “That would be cool.”

Mariana fed the chopped-out numbers one at a time into the laminating machine, which smelled like glue. “You know, I think if we ever had our own company it wouldn’t be that bad,” Mariana said. “I think we could run a school, at least have it all organized.”

* * *

On the second day of the academic year, guidance counselors told Isaias to start an application to a local college, Christian Brothers University, and he obeyed. But he had mixed feelings about college. “It’s really interesting. But when I think a little deeper about it I think—what is it, why? Why? Why should I go to college? Why? I mean everybody tells you to get a good job, right? But I think about a good job doing what? A college degree gives you the ability, but not the actual job. And I guess from my mindset I just don’t see college as being that important.” He weighed becoming a civil engineer against other ideas: traveling the world as a singer-songwriter or working with his parents.

He said he’d go if he got a scholarship. “But if not, I’m not going to hassle too much, I’m not going to worry about it.” Later that month, Isaias’ father told me his son had changed his mind. He was trying to go to college.