Early July 2013:

A month and a half after graduation

TWO DAYS AFTER GREGORIA’S FUNERAL, the members of the Ramos family took a day off and prepared to repaint the outside of their home in Memphis. Then a minivan pulled up.

Out stepped Adriana Garza, the recruiter from Victory University. ¡Felicidades! she said—Isaias had won the scholarship!

Mario and Cristina were elated. But Isaias showed much less enthusiasm. Ms. Garza had already called Isaias on his cell phone when he was eating breakfast and told him the news. The scholarship covered tuition, and he’d only have to pay for his books. But Isaias hadn’t passed the news along to his parents. The only reason Ms. Garza had come to the house was that she’d passed by with her husband, who specialized in selling insurance to the Hispanic market, and when he saw the Hispanic family, he wanted to stop and give them his business card. Then Ms. Garza recognized Isaias.

The muted reaction from Isaias didn’t shock the recruiter. Students usually wanted to go to other, more established schools, and Victory meant disappointment. Sometimes she’d beg them to come.

In Isaias, though, Ms. Garza was meeting someone who felt ambivalent not just about this particular university, but about the idea of college itself. Isaias said he didn’t know if he’d accept.1

* * *

Victory was a for-profit institution, and it was losing money. So why did it let students like Isaias attend for free?

University president Shirley Robinson Pippins said that by giving scholarships to athletes and to high-performing students, Victory boosted its image and made itself a more diverse and attractive environment. That, in turn, would draw students who might otherwise not have applied.

Moreover, Dr. Pippins said she believed in opening opportunities to students who might not get them elsewhere. “That’s just something near and dear to my heart and then I think also within the Christian mission of a school like Victory.”

Mariana Hernandez had planned to go to Victory University, too. But she said Ms. Garza had told her the school was having financial problems, especially with scholarship money, and that the staffer’s own job was in jeopardy because of the issues. So shortly before the first semester started, Mariana enrolled at Mid-South Community College, just across the river in Arkansas. She paid out-of-state tuition, but it was cheaper than the out-of-state rate she’d have to pay at public schools in Tennessee, where she lived.

Mariana’s case illustrated that even though students with immigration problems were priced out of some universities, they sometimes found ways to keep studying. But Jose Perez, the student leader in JROTC, wanted to join the military. That was a different story.

Late in his senior year, he’d shaken off his apathy and started coming to school and doing work again. He achieved something no one on his father’s side of the family had ever done: he graduated from high school. Over and over, he visited the Marine Corps recruitment office. He said that each time, the recruiter told him he needed documents. Finally, Jose got Deferred Action status, went to the Social Security office and applied for a number. They gave him a paper saying he’d soon get a Social Security card, and he immediately went back to the recruiter and showed him the paper. Jose recalled that the recruiter looked at it and said he still couldn’t accept it. This latest rejection shifted something within Jose’s mind—he thought he would never get a chance to join. And he was correct. Under a policy still in effect at the time of this writing in 2015, people with Deferred Action status could not join the Marines. Similar restrictions were in effect for other branches of the military.

Jose said that after that last meeting with the recruiter, he went home and cried for nearly the whole day, then the day after. For days after that, he hid in his room.

Everything he’d done in JROTC in high school seemed like a joke, like playing dress-up or playing with Barbie dolls. He remembered putting the old JROTC uniform on the doorknob of his closet and staring at it for a long time. He felt afraid to put it on or touch it because it represented the only connection he still had to the military. He said it took him a month or two to recover from the depression. At the time we spoke in April 2014, he was working in his uncle’s remodeling company and sometimes in a Mexican restaurant. He said he kept the room he shared with his girlfriend stuffed with Marine Corps gear, even Marine Corps sheets. He was wearing a Marine Corps t-shirt when we spoke, and he said he still went home every day and looked at the JROTC uniform. “And I’m like, man, it would have been so different if I had been born here.”

In November 2015, Jose’s Facebook page still prominently displayed a 2012 photo of himself in fatigues, standing next to the Marine recruiter.

* * *

While Jose struggled, Estevon Odria seemed to find a sort of peace in the months before he headed to Carnegie Mellon. In July, he sent a Facebook message to his mother, Nadine. Estevon and Nadine had clashed often. Now he sought to make amends.

“Dear my beloved mother: I am truly sorry and apologize for my disrespectful and spiteful attitude toward you at times,” he wrote. “I have realized how much it has hurt you. I want you to know that I forgive and love you with all my heart even if I refuse to communicate with you at times.”

Nadine took Estevon out to eat before he went to college, and then they went out to eat again with his grandparents. “The night before he left, we sat there and took pictures and stuff and I told him to answer my phone calls and he hasn’t,” Nadine said. “He told me I had to e-mail him.” She gave a small laugh.

Still, Nadine felt that her decision not to raise him herself had been for the best. He had turned out well. “So I did something right,” she said.

I spoke with Estevon by phone in September 2015, just days after he’d begun his third year of college. He said he felt different from most of the people there—but that was okay.

Different how? “I don’t know. They just seem very like middle-, upper-class people. Or like, they really haven’t gotten much experience of life or something like that.” At Carnegie Mellon, he had chosen a hard subject, electrical and computer engineering. He wasn’t prepared at first. “What happened was, the first year was horrible,” Estevon said.

Estevon took several difficult courses in his first semester, including Fundamentals of Programming and Computer Science, also known as 15-112. Bloomberg news service featured this course in an article headlined “Five of the Best Computer Science Classes in the U.S.—This Is Where the Smartest Coders Cut Their Teeth.”2

Estevon said homework assignments could take ten hours, and the course also required a major project, such as making a game from scratch. That first semester, Estevon dropped 15-112 without completing it. The first year was so tough that Estevon’s grandfather feared he might drop out entirely. Estevon somehow got through the year.

“And then, like, the first semester of my sophomore year was really bad also,” Estevon said. He retook 15-112 that fall and passed it. Finally, in the second semester of his sophomore year, Estevon began to get the hang of Carnegie Mellon work. It was his best semester so far.

I asked about his grades. “They’re all right,” he said. “I mean, it’s a pretty tough major and the average GPA is like a 2.8 for my major. So I’ll just leave it at that.”

Estevon appeared likely to graduate from Carnegie Mellon and to reap financial rewards. Companies fought to recruit the university’s students, and recent graduates in his major earned a median starting salary of $86,000. They had gone to work for corporations including Amazon, Facebook, General Motors, Goldman Sachs, Google, Microsoft, Samsung and SpaceX.3

Estevon said he was focused on right now and was not thinking much about life after graduation. “I’ll just take it as it comes.”

* * *

Isaias finally made a decision about college.

On the Fourth of July, the Ramos family finished work early. Cristina made hamburgers with thick chunks of cheddar cheese. The boys ate them fast and retreated to Dennis’ room to play video games. Outside, small American flags fluttered in the decorative metal grating of the porch pillars, where Dustin had put them some days earlier.

I had just come back from Mexico, and when I visited that day I gave Mario and Cristina some presents in the kitchen—a plastic container of mole cooking spice that their friend Maria the cake entrepreneur had sent them, a decorated roof tile that I had bought from a member of Blankita Chica’s family, a plastic-wrapped container of chocolate chunks for drinks, and a little tin of sweets that I had bought in the Mexico City airport. I also showed them some of the pictures I had taken with my cell phone, and I gave them some of the obsidian rocks that I had picked up in Cristina’s village on the hill. Cristina recalled how as children, she and other kids had played with these rocks. Dustin, the little brother they called Pato, or Duck, came into the kitchen and saw the rocks. “What is that?” he said in English.

“Se llaman obsidianas,” Mario said in Spanish.

“Obsidian?” Dustin answered, in English again.

I went to Dennis’ room, where he and Isaias were playing the video game Battlefield 4. They paused the game, and Isaias gave his verdict on the Victory University scholarship. “Not bad. I think I’ll end up going. It can’t hurt, right?” Dennis said he’d like to see Isaias go to school full-time. “And get it over with as soon as possible.”

And the day came that fall when Isaias took his backpack and drove off to start classes at Victory. His father watched Isaias with what he called hormigueo, a tingling, happy sense of excitement.

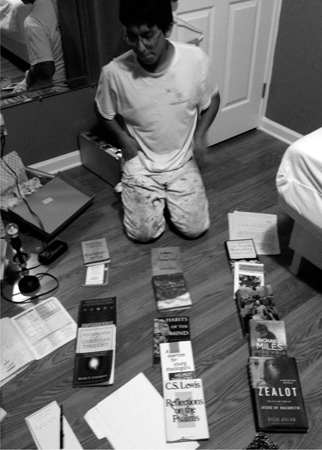

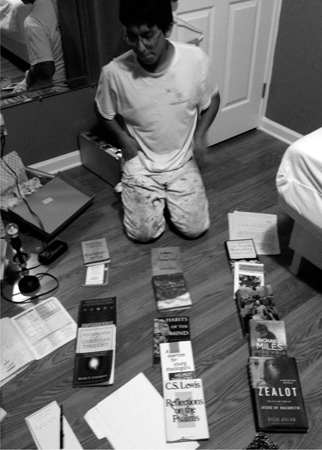

Isaias thrived in college. One Sunday in October 2013, five months after graduation, I went to the family’s house. Isaias had just come back from work and still wore his white paint-specked pants and white t-shirt with the Porter Paints logo.

Never had he done so much reading, but he liked it, and he was having lots of fun learning. “Especially the religious classes. The religious classes are great sometimes.” He showed me the books he was reading, laying them out on the hardwood floor of his bedroom.

They numbered 15 in all, including the classic writing guide The Elements of Style as well as a blue-bound Bible that Adriana Garza, the recruiter, had given him. He had read Foundations of Christian Thought, which compared Christianity to other world views, including secular humanism, then concluded that Christianity was true. “I think that’s the only funny part, that in the end they’re all wrong, Christianity’s right,” said Isaias, who still identified as an atheist. “Otherwise it’s a decent book.”

(Photo by Daniel Connolly)

But he’d also been assigned secular works, including Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, a new book by a Muslim author named Reza Aslan who questioned biblical teaching, examined the historical Jesus and concluded he was a Jewish rebel against the Roman Empire.

Isaias said he wouldn’t know if he wanted to stay in college for the long term until he started taking classes for his major, business. He hadn’t talked about audio recording for a long time. Right now, he saw himself in a wait-it-out moment. “See what happens. Do your best. Don’t ruin your opportunity, ’cause you don’t know yet.”

A few months later, Victory University shut down.