October 2014:

One year and five months after graduation

ONE EVENING, Mario and Cristina were talking in their kitchen with their old friend Paulina Badillo Garcia, the woman with long, curly dark hair who had worked for them in their sewing shop in Santa Maria Asunción and sheltered them when they first arrived in Memphis. Paulina had brought her seven-month-old baby son, and Cristina played with him, cheerful and laughing. Now the baby’s mother cradled the infant as they spoke, and Mario and Cristina let slip that they were going back to Mexico.

“Soon?” Paulina asked, surprised.

“Yes, in a month or two,” Mario said.

“Seriously?” Paulina asked.

“Yes!”

They hadn’t told many people. “Yes, we’re going now,” Mario said. “We want to go live in Santa Maria, the beach. Cristina says Chile. We don’t know yet.” They had thought about applying for immigration visas to several different countries, like Argentina, Germany, Italy and Spain. They would see which country accepted them first, then go there.

“We’ll go on another adventure,” Mario said. “We’ll see what happens. I don’t want to die in Memphis. I don’t want to die in the same place.”

Another reason drove them to consider going back to Mexico. They still owned property there, the old house and some other parcels, and they could sell it, but they believed they’d have to do so in person. They also feared losing ownership of the property and wanted to handle the transaction sooner rather than later.

They planned to leave around January and were counting down their last days in Memphis. Cristina said people sometimes questioned her actions. Why did she plant trees in the yard if she was about to leave? She said she wanted to keep working until the last moment, just as she had in the beginning.

“And the boy?” Paulina asked, meaning Dustin. “Is he going with you?”

“No, he’ll stay,” Mario said.

“We’ll send for him,” Cristina said. “Later. When I’m doing well and I see that there’s not crime. That’s what we’re afraid of.”

They talked about a Mexican tradition: if you’re about to leave on a journey, your mother blesses you and says, “May God be with you.” Now it would be reversed: instead of the parents saying this to their children, the children, Dennis and Isaias, would say this to their parents.

Isaias and Dennis said they had come to terms with their parents’ departure. “Yeah, I just accept it, you know?” Isaias said. “Not angry.”

If Mario and Cristina returned to Mexico, it might take them years to come back to Memphis, and it might ultimately prove impossible to do it legally.

Mario said friends of Mariana Hernandez’s parents had asked him why they were going. Weren’t they afraid of losing everything they had? He said he told them no, he wasn’t. “I can find a new world. A new story, something new to tell. A new life.”

They would start from scratch, carrying only the basics on the airplane home, just some clothes and a toothbrush. “And your soap,” Cristina told her husband. “So you don’t stink.” He laughed. But the prospect of leaving also bothered Cristina. She and Mario told Paulina about a strange dream she’d had: that her husband had thrown out everything from the house in Santa Maria that he didn’t like, and that only a vacant lot remained. And then in the dream, Cristina talked with God, telling him she was afraid of the good, easy life because it becomes a habit, and habits can kill you. “We’re a little anxious,” Cristina told Paulina at the table. And she and Mario realized that people in Mexico might not take them back, might think of them as different, no longer the old friends they had known.

* * *

During his year at Victory University, Isaias had earned perfect grades, a 4.0. Magaly enrolled at Rhodes College in the fall of 2014, and Isaias, no longer in school, sometimes helped with her homework. He borrowed a book Magaly had read in class, a graphic novel called Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel. Isaias enjoyed it. “It’s pretty cool.”

He said he liked reading and discussing books like these—actually learning—but he didn’t like the structured education system. “I guess if there’s ever something that’s like college but not the way it is today, I’d consider going there.”

It hurt his parents to see him lose interest in school. “It’s a year thrown in the garbage,” Mario said. As Cristina saw it, the problem wasn’t in the outside world, but within Isaias. She said Isaias had plenty of ways to find scholarship money if he wanted to. Their longtime painting clients loved him and would help. He could ask at churches. “If you ask me to look for scholarships, I can’t, because I don’t speak English, for a lot of reasons,” Cristina said. “But he can. And he doesn’t do it.” And Mario and Cristina were willing to pay some money toward his education, too.

I asked Isaias more than a year after the shutdown of Victory University if he saw continuing college as impossible. He responded quickly. “No. No. It’s not that. It’s just that I don’t want to.” While Isaias’ decision mystified and disappointed many people, including his own parents, it made more sense if you considered his relationship with another key person in his life: Dennis.

When Isaias was studying at Victory University, he spent less time on painting work, and the family seriously considered hiring someone to replace him in the business. If Isaias kept going to college and his parents moved to Mexico, Dennis would have to handle the painting business largely by himself, along with one or more new employees who might not share the same commitment to quality that had won the family more clients than they could handle. And any college solution would also be likely to cost money, possibly increasing the burden on Dennis.

It took me a long time to develop the theory I just described, and in 2015, I ran it by Isaias. He said it was basically correct. “Yeah, if I had just continued school, problems would have arisen,” Isaias said. “I think we all saw it, everybody in the family saw it. How’s Dennis going to take care of everything by himself? How am I going to go to school every day and then come home and, like, got to do schoolwork and still got to do something around the house to help? It would just be difficult.”

I also asked Dennis about the scenario of him largely running the business by himself. “Yes, actually, we did think about that,” he said. He said he would have had to hire other people, but it would have been possible. He also said family members had considered helping Isaias pursue school. “If he really wanted to, we would have let him continue studying,” he said.

* * *

Isaias’ former classmate Adam Truong said he didn’t really want to go to college, either. But he did anyway. He was studying mechanical engineering at Christian Brothers University.

People told him he’d learn 90 percent of a job on the job. He’d contemplated dropping out of college, but he said his professors told him they all thought the same when they were young, and their friends who dropped out had no job security because they didn’t have the degree.

Adam had imagined that college would give him a chance to explore new topics, but that wasn’t the case, at least not in his major. “As a science major going into college, I feel like everything’s one pathway, and they make you really good in that pathway, and that’s it.” He had thought about switching to chemical or biomedical engineering but concluded that he’d have to take out big loans. So he kept going on the mechanical engineering path.

Looking back at the time at Kingsbury, Adam thought he’d benefited from going to a less-privileged school. It made him understand the world better. Sometimes college students from more privileged backgrounds seemed clueless, especially those he met when he visited his sister, a student at Rhodes. “They have, like, no idea what happens to the other side of Memphis,” Adam said. “No idea at all.”

He and Mariana Hernandez weren’t dating anymore, but they’d talk when they saw each other on the Christian Brothers campus. She’d landed there through a stroke of fortune.

After graduating from Kingsbury in 2013, Mariana had abandoned plans to go to her first-choice school, Christian Brothers, and had enrolled at the most affordable institution she could find, Mid-South Community College. She worked for the social services agency Latino Memphis helping younger students and maintained a close relationship with Jennifer Alejo, the college counselor who had come to Isaias’ house on the night of the intervention.

In the summer of 2014, Ms. Alejo told Mariana of a new opportunity that would allow her to enroll at Christian Brothers after all. “Jennifer just told me to wait it out and that something would happen,” Mariana said. “And she made it happen.” Latino Memphis had helped create a new Christian Brothers scholarship program specifically designed for students with immigration problems. Backed by an anonymous donor’s gift of $150,000, the Latino Student Success Scholarships assisted 14 freshmen and 11 transfer students, including Mariana.1

The transfer students took on $5,000 in loans each year and paid $50 a month toward loan repayment while enrolled in school. They also paid about $3,650 per year toward tuition. That was a lot of money, but much less than the university’s tuition sticker price, about $29,000 per year. And the program also offered $1,000 per year for books.

Ms. Alejo had wanted Isaias to apply, too—this was the opportunity that she’d tried so hard to tell him about. It would have been easy. “This was simply, ‘Hey, fill out a little application and tell me, and that’s all I needed,’” she said.

In the summer of 2015, Christian Brothers announced that it had received another anonymous donation of $3.6 million for the scholarship program. That money plus contributions from the university would support the education of 80 additional students over the next four years, bringing the total in the scholarship program to 105.

The university celebrated the scholarship announcement at a luncheon. One of the special guests was Alejandra Ceja, leader of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics. After the luncheon, backers of the scholarship met with corporate leaders at the downtown offices of the Greater Memphis Chamber, the city’s top business organization. Mariana joined them, looking mature and elegant in a formfitting green dress with a leaf pattern, and she took a seat in a conference room next to another Christian Brothers student named Bryan Nunez.

The 20 or so people around the table introduced themselves. They represented some of the city’s most powerful institutions and companies: the city mayor’s office, the school system, FedEx. Mariana introduced herself as a CBU student and employee of Latino Memphis. Silently, she asked herself, “What am I doing here?”

But the business leaders showed an interest in her. “The Latino population is one that’s actually growing in Memphis,” said Phil Trenary, a former airline executive who now led the chamber. “Our population has not grown that much in the past 20 years. And this is an area that we see as a tremendous opportunity.”

The chamber was trying to recruit businesses to invest in Memphis, and the companies needed educated workers. Mr. Trenary turned to Mariana and Bryan. “You two, you’ve got to stay here. That’s part of the deal. You’re not allowed to leave the chamber until you sign a pledge of long-term residence.” The people around the table laughed. Mariana was sitting close to Bryan, her bare right shoulder touching his shirtsleeve. Later she said they were dating.

State lawmaker Mark White told the group that a few months earlier, the Tennessee legislature almost passed a law that would have allowed students like Mariana to get in-state tuition at public universities, but it fell short by one vote. He would try to push the bill again in January, with the backing of the business group. Mauricio Calvo from Latino Memphis noted the progress. “Not even 20 years ago, two years ago, we could not have dreamed of having an in-state tuition bill getting out of a subcommittee.”

The meeting broke up, and the head of the chamber, one of the most powerful men in the city, walked over to Mariana and handed her a business card. “Okay, if you need me at all, I’m Phil.” And then Mariana was talking to Alejandra Ceja from the White House Initiative, who described how her staff took interns to the president’s mansion to go bowling in its private recreational space.

If bowling at the White House sounds impossible for someone like Mariana, consider this: A few months after the meeting at the Greater Memphis Chamber, the Christian Brothers University president John Smarrelli, Jr. traveled to Washington for a twenty-fifth anniversary celebration of the White House Initiative. He brought with him a CBU student: Franklin Paz Arita, the kid from Honduras who’d spent the first week of school in 2012 sitting in the Kingsbury gymnasium, the one who had witnessed a man threaten to kill his mother with a sledgehammer years earlier.

Franklin went to the White House reception and was one of a small number of people allowed into a VIP area. He shook hands with Vice President Joe Biden. Then Franklin met President Obama and spoke with him.

“He just said that it was an honor to have us as guests there,” Franklin recalled. “And I told him that because of him and Deferred Action and because of CBU, my dreams have been revived. And he just said that it meant a lot to him.” They shook hands and posed for pictures.

Franklin recognized that being an honored guest at the White House was a special privilege. “And it also motivates me to keep trying,” Franklin said. “To be the best possible version of myself that I can be, you know.”

This really happened. Perhaps something like it could happen for Mariana, too. Maybe the day after the meeting with the business leaders she would go back to being a struggling college student. But for this moment she stood close, so close, to great things.

* * *

August 2015:

About two years and three months after graduation

For now, Isaias stayed on a different course.

One day Isaias and Dennis went to work in the country at a big new farmhouse-style home owned by an old client and friend, Michelle Betts. They prepped a room for painting and then used rollers and brushes to turn the wall from green to white. Isaias set his phone to play music: the French rock band Phoenix, a classical version of Ave Maria, British hip hop by Gorrillaz. The brothers’ own band, Los Psychosis, still played together. Tommy the drummer had left the band and now Stephanie, the wife of Javi Arcega, had played drums in several of their shows.

Isaias felt optimistic about the future. “I guess I think of getting married. Kind of cool. I like that. Being with Magaly all day. That’s pretty fun, right? I’m excited for that.” They had talked about it but wouldn’t rush in—perhaps they’d take that step in three or four years, after she had finished college. They’d skip straight to living in a house, not renting an apartment. Isaias thought about moving out to a Memphis suburb, perhaps Bartlett in the east. They’d figure it out later.

“I guess I like to make plans like that, but a lot of times skip the details,” Isaias said. “’Cause details always go wrong.”

Magaly was about to start her second year at Rhodes College, and it seemed to be working out well for her. The private school was both selective and expensive: each year, commuting students would pay $43,000, and those who lived on campus paid $54,000. Magaly was a U.S. citizen, and between the college’s scholarships and federal financial aid, she didn’t have to pay anything. In the second year, she anticipated she’d have to pay only $500 out of pocket.

She still lived at home with her mother and now she was driving an old white SUV onto a campus where some other students were driving Audis or BMWs.

The classes were hard. She felt she didn’t have enough time in the day to do everything that was required, and she struggled, finishing her first year with a grade point average of 2.83. But despite the difficult work and the differences between Magaly and many other Rhodes students, she’d made some friends on campus and she’d taken one-on-one lessons on her favorite instrument, the flute, and learned to play far better than she ever had before. She frequently visited Kingsbury High and planned to become some sort of advisor for the senior class. “I guess I’m closer in age to them, so they might believe me more.”

Though she still thought of becoming a veterinary pathologist, she’d become interested in education and imagined she’d work as a high school teacher before completing a doctorate later.

And Magaly liked the idea of marrying Isaias. “I mean, I guess like the words that come to my mind are cute, adorable,” she said, smiling. “Sweet. I don’t know. I look forward to it.”

As Isaias and Dennis painted the house in the country and listened to the music they loved, their father and mother worked in the next room. The fact that Mario and Cristina were still working with their sons on this day in August 2015 was remarkable, since they had long talked about going back to Mexico—had in fact been on the verge of doing it. But in the end, they didn’t go, at least not yet.

I had visited the Ramos home in December 2014, shortly before Christmas, fully expecting to hear details of the parents’ final preparations to go. Instead, I found the house decorated for the holiday: a little tree on a table in the living room, fruits laid out for ensalada de Nochebuena, the holiday drink they’d make, white icicle lights hanging outside near the little American flags.

Mario told me that about four days earlier, they’d changed their minds about leaving. “Really, it was everyone’s idea. We sat down here eating breakfast, and the idea came up to stay a while longer. I don’t know how long. Three to six months at most.”

Cristina had been excited about going. But she had worried about Dustin since he was still so young. And she thought about the people she knew, people like Michelle Betts, who lived close to their children and grandchildren. She imagined Isaias becoming a father to a grandchild that she could never see. “That’s the feeling that kills me,” she said, and Cristina, usually so cheerful, began to cry.

That December night, Dennis seemed puzzled by his parents’ decision. He’d been trying to convince them to stay a while longer, to earn money to buy one more house to renovate and rent out. “I kept telling them, and they said, ‘No, we’re gonna leave.’ They even got mad at me for asking. And in the end they changed their minds.”

Mario and Cristina still talked about going back. They continued to prepare Dennis and Isaias for their absence by letting them handle important chores, like registering Dustin for seventh grade.

That August, Dennis and Isaias took Dustin shopping for school supplies. He followed his older brothers through the store, a young boy who walked with shoulders hunched forward. The shopping reminded Dennis of his own school days not so long before, when he and Isaias were young. It had been harder then. The family had little money and because Mario and Cristina worked such long hours, they usually shopped at Walmart at the last minute, when the shelves had already been emptied. Now, they shopped three days before school started, and when the cart full of supplies totaled $104.67, Dennis simply paid with a debit card.

What did Dustin think about going back to school? “It is unexpected,” he said. What Dustin meant by “unexpected” was that he’d spent much of the summer playing video games like Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare. When his parents told him he had to go back to class, he wasn’t prepared. “And then I have the shock in my heart that I’m going to school.” His parents and brothers said Dustin actually liked school, and that he’d been doing better since advancing from elementary to middle school the year before.

What was he thinking of doing as an adult? “Uh, that’s a hard question,” he said as he walked with his brothers. His voice was still a boy’s, high-pitched, but he spoke in the slightly accented cadences of his older brothers. “There’s a lawyer and a judge that I want to be,” the boy continued. “But then again, I’m in love with video games, so I could do that. Then there’s a biologist.”

Dennis and Isaias still talked in general terms about going back to school one day. And the older brothers would work to give Dustin a chance to study something he liked, even cooking, or art. For Dennis and Isaias, that was what education should be: something you liked. Dennis said if Dustin didn’t want to go to college, that would be fine, too.

* * *

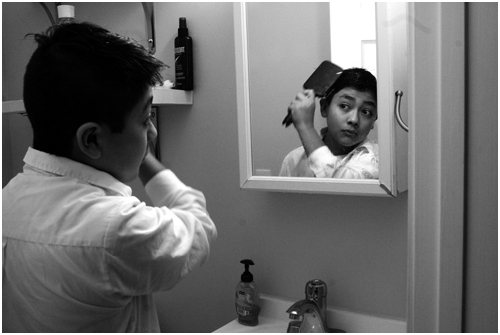

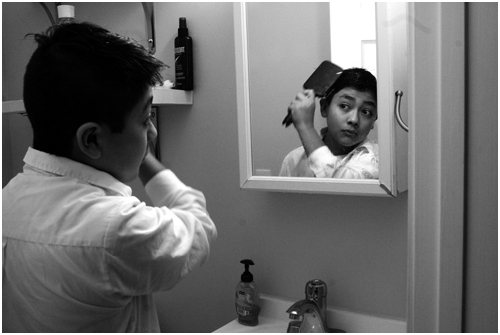

On the morning of August 10, 2015, the same day his parents and brothers would work at Michelle Betts’ house, little Dustin Ramos woke up early, put on his school uniform of tan pants and white shirt and ate breakfast by himself. He was feeling a bit nervous on this first day of school, but prepared, his hair freshly cut short by his mother. He put on the backpack loaded with the supplies his brothers had bought him and sat on the edge of a couch in the living room, waiting. Outside, rain began to fall.

(Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht)

Three years had passed since the chaotic start of Isaias’ senior year in 2012. If all went well, Dustin would graduate from high school in 2021.

Maybe Dustin would prove an average student. Maybe he would drop out. Maybe he’d climb to the very top of his class, as Magaly had done.

Maybe one day Dustin’s parents really would go back to Mexico, and he’d spend the next few years shuttling between them and his brothers in Memphis, a young boy walking through international airports. Maybe his parents would stay in America, and the government would grant them papers in a year, or in two years, or in ten years. Or maybe the papers would never come.

But now Dustin was only 11 years old, and all his possible lives branched out in front of him in an endless tree of potential paths. And rain or not, he had to go to school.

“Vámonos, Pato,” his father said. Let’s go, Duck.

The boy rose and moved to the door, and his mother hugged him and spoke to him softly. “Recuerda todo que tienes en tu cabeza y en tu corazón.” Remember everything you have in your head and your heart.

His father stopped the green truck a short distance from the middle school, and Dustin ventured into the rainy semidarkness. He joined the children clustered under the sheltering awnings outside the locked school doors, each waiting with their own fears and desires and hopes. Then the hour arrived, the school doors opened and the children walked inside, and into the future.