Late September through October 2012:

Seven months before graduation

THE BUS PULLED TO A STOP outside the college fair site at a trade show hall. Counselor Patricia Henderson rose and stood in the bus aisle, faced the students and urged them to make good use of the opportunity.

“You only have a certain amount of time,” she said, projecting her voice to the back of the bus.

“How much?” student Tommy Nguyen asked.

It would turn out to be not much time at all. First, organizers led the Kingsbury students into a big auditorium with students from other schools, where they heard speakers tell them why college mattered.

Paul Fisk, a man in greenish-gray combat fatigues, took a turn. “There’s a hundred vendors out there. More. How many people are serious about being here today?” Hands went up. Mr. Fisk dismissed them. “Y’all are all lying because I bet most of you are here for the free pens and goodies on the tables, aren’t you?” The students laughed. “Go out there and take it serious,” he said. Then he painted a bleak picture of what would happen if they didn’t. “Most of you will not go to college. Most of you will serve burgers. A lot of you will be poor. How many of you want to be poor?”

Then the Kingsbury students split into groups and went into small rooms elsewhere in the building. In one room, they did a listening exercise that involved recounting the details of a story about a robbery. In another room, students heard a lecture on personal finance and watched a video on credit card debt. It featured a sexy female devil who hissed, “Charge it! Charge it!” It was unclear what any of this had to do with finding a college, but it took a long time.

Finally, the Kingsbury students were released into a cavernous space divided by blue and white fabric panels. Hundreds of chattering voices echoed loudly. Rows of recruiters stood behind tables, representing colleges, the military, and local employers. Throngs of students from throughout the school system clogged the aisles and made it hard to move.

Isaias separated from the other Kingsbury students and walked through the aisles by himself—no plan, just looking for something to catch his eye.

He found it: a booth for a student-run radio station. Isaias was spending three hours a day in a sound recording class at the vocational center near the high school. He loved the work mixing music and radio plays. Now Isaias leaned across the table to talk with an African-American man with graying hair. This man told him the school system operated its own FM radio station and that students could get training. “Through Memphis City Schools, it’s free!” the man said. “Really?” Isaias asked. Bad news: it was a three-year program and Isaias couldn’t do it because he was already a senior. Isaias seemed disappointed. But the radio man kept going.

“What are you thinking about doing next year?”

“Maybe college. Maybe work for a year and then college.”

Just then, a loudspeaker announcement broke through the echoing shouts. “Kingsbury students move to the holding area.” The students had just begun to explore the colleges, but they were already running out of time. Maybe the St. George’s parents would take their children for a leisurely stroll among the aisles in the evening session of the college fair, but most Kingsbury parents wouldn’t. For Kingsbury students, this was the only shot.

Isaias quickly mentioned his interest in audio recording. The man recommended audio recording programs at the University of Memphis and Middle Tennessee State University and urged Isaias to apply for scholarships. He offered his business card and Isaias took it.

Excited, Isaias walked away toward the bus. The brief conversation with the radio man had planted a seed. Of course Isaias knew about the University of Memphis campus just a few miles from his house. But until that day, he had never heard of Middle Tennessee State. For the next few months, he would focus his energy on getting there.

* * *

Attendance dropped off at Kingsbury on rainy days since most students walked to school and some had to travel a long way. But Isaias had an unusual privilege, a silver two-door Mazda coupe of his own, and tonight he was driving some friends to Kingsbury’s homecoming football game. Suddenly, blue lights flashed behind him. The speed limit on the road had changed, and he’d missed it.

This could be a real problem.

Memphis had a weak public transportation system. In general, anyone who wanted a normal life had to own a car. Immigrants could buy cars without a license and even register the vehicles with the county government. But like immigrants across the United States, the Memphis newcomers wanted driver’s licenses: the documents made countless other transactions easier and greatly reduced the risk of arrest in a traffic stop.

Each state in the country set its own license requirements. Tennessee had experimented with issuing licenses and more limited “driving certificates” to immigrants who lacked Social Security numbers, but after people came from other states to get them, Tennessee scrapped the programs.1 Now Isaias’ immigration problems meant he couldn’t get a Tennessee license. Like many others in the Kingsbury neighborhood, he drove without a license, and without insurance.

Isaias said he sometimes enjoyed the risk of driving without a license. “I’m living on the edge!” he told Patricia Henderson once. Tonight, though, he might get arrested. And though he and Dennis had applied for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the president’s new legalization program, they hadn’t yet been accepted.

Relief. The officer drove away unexpectedly, perhaps to take another call. Isaias continued to the bright lights of Fairgrounds Stadium, a little field dwarfed by the Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium a short distance away, empty tonight and looming like a warship illuminated in electric blue. The Kingsbury football players were a diverse bunch: among them Jose Garcia, the beefy kid nicknamed “Big Sexy”; Aro Nebk, the Sudanese teen who also played soccer; and Cody Sherman, the white boy with the big smile. They’d struggled all season. Going into this early October game, Kingsbury’s record stood at one win, six defeats.

Kingsbury’s marching band fired brassy musical volleys across the field at the band from Booker T. Washington High, another inner-city school. A boy from a Vietnamese family—Tri Nguyen, whose name was pronounced “tree win”—pounded a set of five small white drums. Mohammad Toutio, who was born in Lebanon, banged a big bass drum.

A small, delicate girl played the flute. Black bangs reached almost all the way down to her large brown eyes. She was Magaly Cruz, quiet and easy to overlook, but arguably the smartest girl in the school, an eleventh grader who would stand at the board in Advanced Placement Chemistry and work out a complex problem in front of everyone. Something had happened between Isaias and Magaly the previous year, a hint of romance that fizzled. Now they moved in the same circles and played on the same Knowledge Bowl team but kept a certain distance. They hadn’t talked about it.

As the band played, Isaias and his friends took a spot in the stands. The game had already begun, and for a change, Kingsbury was winning. A cool, crisp wind picked up, and a banner at the top of the bleachers began to snap. The public address system came to life. “Attention. The game has been called.” The wind began blowing trash around the field. The crowd headed down the bleachers.

And then the stadium lights went out and the rain poured down. What had seemed like an inconvenience now felt like an emergency. Jose Perez, the JROTC leader, screamed to other cadets to stay together. Tri sped to the exit and left behind his portable five-drum set. Isaias picked it up and held it over his head. He left the stadium and walked into the parking lot, where music rang from a bus in the distance: the band from the other school, still playing. Mohammad walked with Isaias, occasionally banging his big bass drum. THUMP! THUMP!

The driving rain flattened Isaias’ puffy hair and spattered the lenses of his glasses. He made his way to the back of one of the yellow Kingsbury school buses that had brought students to the game and scrambled to put the bulky band instruments on board, his brown jacket offering some protection. Magaly appeared behind the bus. “This is the best homecoming ever! We won it!” She had a point: the score was 7–6 when the game was called.

The rain slowed down. Soon Mr. Fuller accounted for all the Kingsbury students, and the buses rolled out of the parking lot. The teams restarted the game days later, and Kingsbury won 38–6. The homecoming ceremonies that had been planned for halftime took place during a pep rally in Kingsbury’s gym. Mr. Fuller put a crown on the head of that year’s homecoming queen, Clarissa Mireles, and Mohammad, Magaly, Tri and the rest of the band rocked the gym with blaring brass and rolling drums. When the audience filed out, the band kept playing all the way to the practice room, where Mohammad jumped up and down banging his drum.

But before any of this happened, while the rain was still falling, Isaias had given his brown jacket to Magaly.

* * *

A few days later, Kingsbury took a busload of students to a local private institution, Rhodes College, as part of a series of college visits. “I feel like I’m in the scene of Harry Potter,” said senior Phalander Peoples, admiring the Gothic-style buildings. The campus impressed Isaias, too. “It doesn’t feel like you’re in Memphis.”

Isaias stuck with Magaly. They ignored the tour guide and examined the environment like children brought to the beach for the first time, picking up every seashell and piece of driftwood.

They stopped to speak with a young man with glasses who was studying sheet music. They examined a sundial. Outside the library door, Magaly pulled the handle of the book drop, swinging it open with a dull metallic clang. She tapped a tile on the floor and said, “It’s hollow.”

The students ate lunch in the cafeteria after the tour and were supposed to meet back at the bus at 1:00 p.m. But Isaias and Magaly were gone. Counselor Brooke Loeffler climbed onto the bus. “Okay,” she told the students. “Who has a cell phone number for Magaly or Isaias?”

A few minutes later, the two of them emerged from the cluster of Gothic buildings, making their way down the green, leafy boulevard toward the bus. “We went to the library,” Isaias said. Ms. Loeffler told them they couldn’t do that. What if something had happened? She didn’t like to see honors students wandering off. It would set a precedent for the adults to set stricter rules on college visits. And how ironic that Isaias had asked why Kingsbury couldn’t be more free and open.

On the bus ride back to Kingsbury, Phalander took a window seat and Isaias sat beside him on the aisle, with Magaly on the bench behind him. She was reading Thinking, Fast and Slow, a book on decision making. Isaias turned toward her and she held it out in the aisle so they could read it together.

Magaly loved libraries. So when she visited Rhodes, her rapid walk-through of the library with the tour group wasn’t enough. “I was like itching to see what was really in there.” She and Isaias went back and explored the place on their own. They were about to leave when they found a thick book on 1920s movies and lost track of time.

Magaly’s mother, Consuelo Padilla, was 44, with graying hair and twinkling eyes, and she laughed often. One day that fall I met her and Magaly at La Michoacana, a Mexican ice cream shop on Summer Avenue near Kingsbury. The shop offered unusual flavors like tequila and corn. On this day I had piñón—pine nut—served heaped above the rim of a white Styrofoam cup. Magaly ate pistachio and her mother had strawberry.

Magaly’s mother came from a town called Teocuitatlán in the state of Jalisco and grew up in a family of nine children living in a little house with just one bedroom, a small kitchen and a living room. A local school offered a basic education, but anyone who wanted more had to go to the city. The family lacked money, so Consuelo left school after sixth grade. In 1990, she moved to Los Angeles, where she worked for several years taking care of children, then as a seamstress. In Los Angeles, she gave birth to Magaly. Magaly’s father never played a role in his daughter’s life, and Consuelo said they hadn’t heard from him in a long time. She turned to Magaly. “How old are you, daughter?” she asked in Spanish. “I think it’s been something like 17 years.”

Now Magaly and her mother formed a tight little family of their own. Years earlier, a friend had brought them to Memphis, where Magaly’s mother cleaned houses.

How did Magaly get so interested in reading? “Maybe it came from her father because it doesn’t come from us,” her mother said. She and Magaly laughed, and Magaly said in Spanish, “I’m the odd one of the family.” But her mother encouraged Magaly’s will to learn and wanted her to seize the opportunities this country offered. During tough times in Los Angeles a few years before, many people she knew had talked about going home to Mexico. Consuelo decided not to—not for her own sake, but for Magaly’s.

Unlike many other Kingsbury students, Magaly didn’t work outside of school. She’d spent the summer doing academic enrichment, including band, an engineering program for girls and a course to prepare her for advanced placement work in the next school year.

Magaly sometimes wrote letters to an imaginary friend, the main character in a novel called Interrupted: Life beyond Words by Rachel Coker. She wanted to become a veterinary pathologist, someone who studies animal diseases. She liked pygmy goats. She became a vegetarian.

Magaly held many things close, and only much later did she share defining facts of her young life: how her shyness sometimes felt overwhelming, as though she would rather stare at a wall than talk to people. How her mother had a long relationship with a conservative man who didn’t believe a girl should go into the world and try to learn. How she spent hours alone in her room, listening to classical music and reading, an attempt to escape from the fate the man wanted for her, that of an ignorant housewife. This man she described as her stepfather had left before her junior year, before our talk at the ice cream shop.

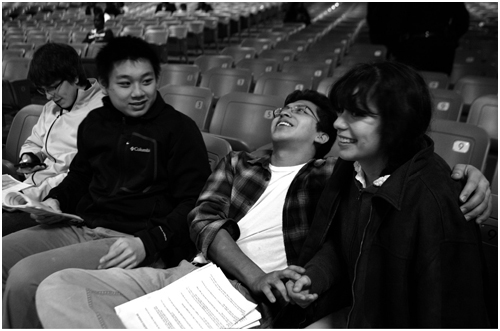

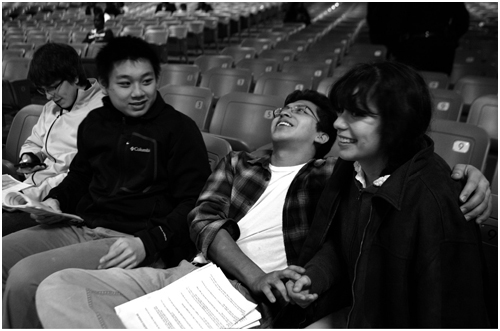

Isaias lets Magaly wear his jacket during a break at a Knowledge Bowl competition, with teammates Daniel Nix and Adam Truong at left. (Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

By the time Isaias visited the Memphis University School campus for a Knowledge Bowl tournament later in October, his romance with Magaly had become obvious. Magaly played on the Knowledge Bowl team, too, and in the courtyard between games, Isaias held his arm around her for long moments. She and Isaias chatted with each other online, sometimes writing backward messages. Later in the year, Isaias carried the massive double bass she played. He bought her a dress. In school, he sometimes caressed her face with the back of his hand.

* * *

Isaias and Magaly, two children of Mexican immigrants, almost always spoke with one another in English.

Perhaps that would surprise people like the scholar Samuel P. Huntington, author of a famous 2009 essay called “The Hispanic Challenge.” He warned that immigration might effectively split the United States into two countries and cultures, one English-speaking, one Spanish-speaking. Huntington argued that Hispanic immigration, particularly from Mexico, differed greatly from other immigration waves. “The size, persistence, and concentration of Hispanic immigration tends to perpetuate the use of Spanish through successive generations.”2

Some Kingsbury students had just arrived from Mexico, didn’t speak English well, and took English classes for foreigners. Yet other developments would suggest Huntington was wrong. By 2013, more than two-thirds of U.S. Hispanics reported speaking English proficiently, a trend that reflected an increasing number of Hispanic children born in this country and a slowdown in immigration.

One of the most well-known Spanish-language media personalities was Univision news anchor Jorge Ramos, who told NPR in 2012 that his own children didn’t watch his newscasts. “They get their information in English,” Ramos said. “Their friends don’t watch me. Their generation is not watching us in Spanish. So we have to do something.” Univision joined ABC to launch Fusion, a network for English-speaking Hispanics. The network later shifted focus to young people of all ethnicities.

Though Isaias and Dennis maintained their ability to speak Spanish, their younger brother Dustin, born in the United States, didn’t speak much Spanish at all, nor did many of his friends. Isaias would remark on this later—how strange it was to meet kids with Mexican names like Rogelio and Jose, none of whom spoke good Spanish. Though speaking good English would lead to success in American society, the lack of a common language between children and parents sometimes hindered normal relationships. “It is not uncommon to overhear discussions in which parents and children switch back and forth between languages and completely miss one another’s intent,” researchers Carola and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco wrote in 2001. And kids sometimes used language skills to deceive parents. “A thirteen-year-old Mexican boy admitted to us that he had told his parents that the F on his report card stood for ‘fabulous.’” Sometimes the deception was more serious—a Hispanic officer with the Memphis police told me that because the second generation’s main language was English, some parents didn’t realize their children were involved in gangs. “Parents aren’t even aware of what’s happening, even when it’s in front of them.”

Isaias’ mother Cristina said that when she spoke with Dustin, it was usually to express maternal love. If Dustin needed to speak with her about something more serious—a school matter, for instance—she got Isaias to interpret.

* * *

Churches dotted the neighborhood around Kingsbury High School, and one of them, Iglesia Bella Vista, put on a one-day soccer clinic for boys and girls as part of its outreach efforts.

Many volunteers had come to the Streets Ministries community center to help, including a teenager with a handsome face, large ears and a V-shaped, muscular torso, like a welterweight boxer. He was Rigo Navarro, the best goalie on Kingsbury’s soccer team. When the time came for the kids to practice their new shooting skills, Rigo let them try to kick goals past him, and for the little ones, he dropped to his knees so they’d have a chance.

Rigo lived near Isaias and considered him a friend, but they weren’t close. Rigo had dated Mariana Hernandez for a time, but that had ended a while ago.

Several days after the soccer clinic I visited Rigo’s house, one of the most beautiful I’d seen in the neighborhood. Pink roses bloomed near the entrance. An ample porch housed an upright piano and birdcages with chirping zebra finches, cockatiels and little quails pecking around the bottom. Rigo came from a big family and had many nieces and nephews, and toys, including a child-sized plastic kitchen, were scattered on the porch.

Rigo Navarro. (Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

Rigo introduced me to his father, Rosalio Navarro, who was 59 and graying, and had the same large ears as Rigo. We settled on the porch, and Rigo’s father told me that 17-year-old Rigo was his baby, the youngest of his nine children. The oldest were in their 30s.

Rosalio Navarro had grown up in Tequila, the city in Mexico’s Jalisco state that was known for producing liquor, and he’d worked for many years in the grinding, low-paid job of harvesting and hauling the agave plants used to make the drink. As Rigo’s father talked about growing up so poor that he didn’t have shoes, Rigo played with an iPhone.

As a young man, Mr. Navarro entered the United States illegally to work, and for years he traveled back and forth to his home in Mexico. His wife remained at home and bore him several children. When the 1986 amnesty arrived, he got his green card in Fresno, California.

He eventually attained citizenship and applied for papers for other members of his family, including Rigo, whom family members had brought to the United States illegally when he was seven.

Certain immigration procedures had to be done at U.S. consulates outside the country. The immigration process required a teenaged Rigo and one of his brothers to spend several scary weeks in Ciudad Juarez, a Mexican border city that at the time was one of the world’s most violent places. At the end of it, though, Rigo got his green card, a coveted document that let him work indefinitely in America and would also make him eligible for federal student aid for college.

Rigo worked construction and sometimes as a waiter at catered events. He loved soccer. Kingsbury fielded a strong team and had a shot at winning the state title in the spring, and Rigo hoped his success as goalie would help him win an athletic scholarship to go to college—none of his five older brothers or three older sisters had studied at the university level. He also thought about joining the military and becoming a helicopter pilot, then perhaps a chef. Or if he went to college, he might join ROTC.

Rigo’s father earned about $500 per week in a construction job and sometimes brought in extra through side work. Rigo’s mother rarely worked outside the home. Rigo’s father said he couldn’t help his son pay for college. “I pay for the house, I pay for the light and all this, and I always end up with nothing.”

Rosalio Navarro told me that when he grew up in Mexico, his family had so little money that he went to school without notebooks and pencils. During recess, he used to sneak into the classroom, find another student’s pencil and break off a piece to use. He told his parents he didn’t want to go to school anymore, and they said he didn’t have to. So he dropped out and started working.

He was in third grade.

Now Mr. Navarro had trouble understanding Kingsbury’s attempts to explain the higher education system to parents. In late October, the school put on an evening session in the library about the college admissions and financial aid process. The session was almost entirely in English. Principal Fuller would later say he couldn’t remember why the school hadn’t made arrangements for an interpreter that night. Rigo’s father came, and afterward I asked him what he thought. “I don’t think much about it, because I don’t understand much of what they’re saying,” he said in Spanish. He said he’d asked Rigo to pay close attention.

Mr. Navarro’s problems at the college session pointed to a broader issue. Immigrant parents often didn’t have enough English skills and literacy to help their children engage with education, even in preschool. Programs that helped adults build those skills were facing funding cuts. One example was a federal Department of Education program called Even Start, which aimed to teach literacy to less-educated parents while encouraging them to become full partners in their children’s education. About half of participating parents were Hispanic. But Even Start faced bad evaluations, funding was eliminated in 2011, and similar programs were generally “under-resourced and disjointed in their delivery,” a Migration Policy Institute report said. In many cases, schools across the United States had serious difficulty communicating with immigrant parents.3

As I left Rigo’s home that evening early in the fall, his father noticed a pencil lying on the porch. Perhaps one of the young children in the family had dropped it there. He held up the yellow pencil. “After all that I suffered—now they’re just thrown around!”

After that, I drove straight to a college recruiting event at a Memphis hotel, where representatives of Harvard and several other ultra-selective schools took turns going to the podium. Each one described their institution as a sort of academic Disneyland. You can study whatever you want! It’s totally open-ended and everyone’s brilliant! At Duke you could even study lemurs.

“We like to joke that the student-to-palm-tree ratio is four to one,” the recruiter from Stanford University in California said, adding that, of course, adults would want to visit their kids at college. “I highly recommend the vineyards of Napa. Parents?”

I thought of Rigo’s dad. It was absurd to imagine that Rigo would even think of applying to Stanford, that his academic record would be strong enough to get in, or that his parents would spend hundreds of dollars to fly across the country to visit him and drink wine. The recruiter’s comment reminded me of the chasm of education, wealth and social wherewithal that separated many children of Hispanic immigrants from their better-off peers.

In his senior year, Rigo struggled with a knee injury that threatened his athletic performance. But an even more important threat to Rigo’s future was his shaky academic record. He’d missed much of eleventh grade and failed English 3. Now, in his senior year, he would take English 3 and English 4, both with Philip Tuminaro.

Rigo said that this year, he’d have to focus on school. “My future depends on it.”

Could Rigo keep his grades up? Would he choose to join the military? Could he become the first in his family to go to college? Would he emerge as a star soccer player and help take his team to the state title? Right now, his future was entirely open.

* * *

That fall, Rigo filled out a form in his seventh-period English class, taught by Mr. Tuminaro and a young assistant teacher, Corey VanHuystee. The first question on the form was “How many books did you read this year?” Like many other students in the class, Rigo wrote “one.”

“Say ‘hey’ if the last book you read was only because someone told you to read it,” the assistant teacher said. “Hey,” Rigo said, along with some others. “I don’t like reading,” he said after class. “I usually have a tough time pronouncing words and understanding words that I don’t know.” But he liked some Greek mythology books with illustrations that he’d read in the ninth grade.

Through the course of the year, Mr. Tuminaro and Mr. VanHuystee tried different strategies to improve the reading level of their students. For a while, they gave them extremely difficult passages to read, in the hopes that they’d learn more by struggling through. But even at the end of the year, some students continued to make basic mistakes in reading and writing, like forgetting to capitalize the first words in sentences. “They shouldn’t have reached twelfth grade not being able to read,” Mr. Tuminaro said. “It’s partially their fault and partially the system’s fault.”

Despite Rigo’s professed lack of interest in reading, Mr. Tuminaro considered him a bright, promising student. And either way, the teacher believed in helping people improve from where they were. Yes, many of the kids read poorly. “But that’s why we’re here,” Mr. Tuminaro said. “If they all understood, we’d be out of a job.”

Mr. Tuminaro was a slender, olive-skinned 28-year-old from Poughkeepsie, New York. His mother had come from Bolivia, and his father was Italian-American. Many other teachers had landed at Kingsbury through Teach for America or the program that brought Mr. Tuminaro, Memphis Teacher Residency. Mr. Tuminaro said his faith in God kept him going. “He brought me here and the work is hard, but I really, really do love what I do. Really love some of these students.”

Mr. Tuminaro believed in living where he taught, and he and his wife rented a house near the school. One time he drove me around the neighborhood and pointed to a fence where homeowners were fighting a long-standing battle with people spraying gang graffiti. They’d paint the fence, then the taggers would come and deface it again. On another street, Mr. Tuminaro mentioned that someone had been shot in the leg there and had survived. “He ended up being the kid that mowed my lawn for a while later on.” Mr. Tuminaro stopped to get fuel at a gas station and had to raise his voice as he spoke with the clerk over the pounding reggaeton music. Continuing our tour, he pointed out Jerry’s Sno Cones, an iconic business painted in bright colors that had launched in 1974, back when the neighborhood was still mostly white and working class.

The neighborhood did have some things going for it, Mr. Tuminaro said. Many immigrant families were still intact. But some families led unstable lives.

One day that fall, Mr. Tuminaro tried to call all the parents in his class to deliver progress reports. Reaching parents was no easy task at Kingsbury, since kids often moved from place to place and phones were disconnected. He made the kids who’d come to school that day write down contact information on popsicle sticks that he could use later in drawings to choose random students for class activities. He made calls at the back of the room, sometimes switching to Spanish.

“Do you know who he’s staying with?” Mr. Tuminaro said into the receiver, using English this time.

“No idea?” he continued. “Okay. Have you talked to the school’s guidance counselor about this?”

The student had disappeared—not disappeared as in kidnapped, but refusing to tell his mom where he was staying. Mr. Tuminaro could relate; as a teenager, he’d often gotten in trouble with his mother and, as a result, had to stay with friends for a while.

The seventh-period English 4 class proved a discipline challenge, too, with students slacking off and talking out of turn. To get the group under control, Mr. Tuminaro and Mr. VanHuystee made a project of working out a sort of contract between themselves and the class. They called it “How we roll,” and they made lists of what the teachers expected from students and what the students expected from teachers.

One student undermined the spirit of the thing by scribbling a sarcastic phrase on a board at the side of the room: “How we roll, modafuckas.”

But Rigo was among the students who gave a constructive suggestion for how teachers should treat kids.

“Not to give up on us,” Rigo said.

“Don’t give up on us,” Mr. VanHuystee said and wrote it on the board.

* * *

It might be easy to write off Kingsbury students as hopeless. But even as students in Mr. Tuminaro’s class struggled with the fundamentals of reading they should have learned years earlier, students in Jihad Haidar’s AP Chemistry class answered questions like this:

10.0 g of acetic acid (CH3CO2H) reacts with 10.0 g of lead (II) hydroxide to form … lead (II) acetate (Pb(CH3CO2)2) and water. Which reactant is in excess? How many grams of it will remain after the reaction goes to completion? How many grams of lead (II) acetate will form?

Compared to the problems that came later in the year, that question from a class worksheet was easy. Students like Magaly Cruz, Mariana Hernandez, Estevon Odria, Franklin Paz Arita and Adam Truong dealt with material so difficult that I didn’t come close to understanding it, and I was an adult with a college degree.

If watching the English 4 class left me dismayed at what some Kingsbury kids couldn’t do, watching AP Chemistry left me astonished at what others could.

Thirty years old, with dark brown skin, black hair and a round face like a cherub, Jihad Haidar was born in Lebanon in 1982 at a time when Israeli jets were bombing the country. Because he led the soccer team, everyone called him Coach Haidar.

At 17, he’d come to America to study and made extra money working in convenience stores. He was Muslim and was married to a Christian woman from the area. He said he didn’t practice his faith very much, but he still fasted and did his best to help the poor and volunteer in the community. The word jihad—his first name—could be translated as “holy war,” but it also meant struggling to live correctly. “So, for example, if you work hard to feed your family, that’s called a form of jihad,” Coach Haidar said. He was well liked among the Kingsbury staff and as a teacher and coach, he set big goals. He urged the soccer players to go for the state championship in their division. They’d come in second twice. Now he was teaching Advanced Placement Chemistry for the first time, and his students would take a tough national exam in May that would give them a shot at college credit. The test was so hard that barely half of students in the country managed to pass. In the hallway one day, another teacher had told Coach Haidar that he hoped one of the students would make a three, the lowest passing score. But a three wasn’t enough for Coach Haidar. He wanted his students to make fours and fives, the highest marks possible.

Doing this was hard without supplies. Coach Haidar said he’d been waiting for weeks for the district to send him books and lab kits for his AP Chemistry class. He’d been using other written materials and paying for lab supplies out of his own pocket. In September, he said he would give the district one week. If nothing showed up, he’d go to the district officials and ask them the obvious question: Do you want this class to continue or not?

The lab kits finally arrived on October 10. The books arrived on October 15. The school year was well over two months old.

* * *

Isaias continued his college search. One day that October he took a seat in a classroom next to his friend Daniel Nix, ready to listen to Brandon Chapman, the tall African-American recruiter visiting Kingsbury from Middle Tennessee State University.

If Harvard was an exclusive French restaurant with white tablecloths, Middle Tennessee State was fast food. And indeed, Mr. Chapman started his talk by telling the group of Kingsbury kids that the university’s student union had a new Popeye’s Chicken franchise. The students responded with approving laughter and murmurs.

“I know y’all like Popeye’s,” said the recruiter, who wore glasses and a shirt and tie. He went on: the student union offered a Panda Express, a taco bar, a potato bar, Dunkin’ Donuts and the new Blue Raider Grill, which was like Chili’s. “All included in your meal plan at MTSU!”

He told them more about the university: it had just completed a $147 million science building, it enrolled 25,000 students, and it automatically accepted anyone who met basic grade point average and test score criteria.

For a student like Isaias, MTSU’s admissions standards were easy. The cost was another story: $14,000 a year. But the recruiter said the students could get help through a Tennessee HOPE Scholarship funded by the state lottery. However, Isaias and other kids with immigration problems couldn’t get this scholarship. Ms. Loeffler, the school counselor, asked how MTSU dealt with immigration status.

“Undocumented status is still a touchy subject with all schools in the state of Tennessee,” Mr. Chapman said. “At MTSU because of the policies, you’re going to be considered out of state. So it’s an extra $10,000 that you’re looking at as a cost.”

Mr. Chapman said the university president hated this. “MTSU’s stance is it’s not fair, it’s not right. They graduated from a high school in Tennessee, they should be able to have in-state status. However, there are ‘powers that be’ above us that will not allow us to give them in-state tuition.” Isaias showed no reaction. But he had a question. “Where is MTSU?”

“Where is MTSU? It’s in Murfreesboro. Which, depending on how you drive, is three or four hours away from Memphis.”

Mr. Chapman took more questions and finished with an invitation: MTSU would bring its “True Blue Tour” recruiting event to Memphis later that month. The university president and representatives from all the university’s divisions would come, and he said the Kingsbury students should come, too.

The meeting broke up, and Ms. Loeffler brought Isaias to talk to the recruiter. Someone mentioned his ACT score of 29. The big man put his arm around Isaias and told him he could win a scholarship. “For you, it would be everything.”

“Are you serious?” Isaias asked.

Mr. Chapman pointed to a brochure. “This full amount right here will be covered. So it now becomes a viable option to you because of a score like this.” He gave Isaias a business card, patted him on the back and promised to work out a deal.

“Great!” Isaias said. “That’s really good to hear.”

And Mr. Chapman said that if Isaias made it to the recruiting event on October 24, he would personally introduce him to the university president and vice president. “We can’t let this kid slip through our hands because of a situation we have no control over.”

Several factors made Isaias an attractive candidate for MTSU and other schools. He could bring diversity to MTSU’s majority white campus, where Hispanics made up only 4 percent of the student body. But more important, he had an unusually high test score.

Recruiters for Ivy League schools said that they considered the whole applicant through essays, grades and recommendations. They said standardized tests represented only part of the equation. State universities in Tennessee made no such claim. The admissions process boiled down to grade point average and ACT scores. Competitive universities outside the South, like Harvard, had historically preferred another test, the SAT. But most Memphis students didn’t apply to those schools, and few took the SAT. The ACT was what counted, and it counted for a lot.

A high ACT score could mean automatic admission and thousands of dollars in scholarship money, even if the student had a shaky grade point average. ACT scores were so important that Principal Fuller made them part of his daily mantra on the announcements. “All of our children strive to make 30s on the ACTs!” In September, Estevon Odria, the student who was striving to go to an elite school, scored a 31 on his latest test. The school announced it on the marquee outside:

E ODRIA

30 ON ACT

Which was one point lower than he’d actually scored, but perhaps the idea was that he’d passed the threshold of 30. At Kingsbury, the median ACT score had floated around 16 for years. Roughly 80 percent of students nationwide did better. Even strong Kingsbury students sometimes struggled on the test. That’s why when the recruiter met Isaias, he reacted as though he’d found a shiny nugget of gold.

October 24 arrived. The Middle Tennessee State recruiters brought their traveling show to a banquet hall in Germantown, a wealthy Memphis suburb.

They prepared exhibit spaces for the university’s major departments, including the music recording industry program that had excited Isaias. Students and parents trickled in and began filling plates with food: chicken on skewers, triangles of pita bread with dip, fudge squares. Isaias had said earlier that he planned to come to the event around 5:00 p.m. But that hour had passed, and he hadn’t arrived.

The students and parents settled into rows of chairs as recruiters began to talk about the school. A white woman named Lisa Johnson who worked in sales management for the drug company Pfizer took the microphone and told the audience that her son had just enrolled at MTSU. She’d taken him to see the campus over and over: on the weekend, during the week, on spring break. Now she was an empty nester.

“So making this decision for him was pretty big for me.” She caught herself. “Us making this decision was pretty big.”

Immigrant parents often couldn’t do this sort of work for children. The mentors at school were helping Isaias on his journey to college, but they couldn’t offer as much attention as a parent would. His parents’ ignorance of the system meant that in many ways, he was on his own. The college admissions process required children of immigrants to think like responsible adults, projecting themselves years into the future and imagining the college graduates they could become. But much of the time, they didn’t act like responsible adults. They acted like kids.

Across Memphis, students the same age as Isaias were blowing opportunities to win thousands of dollars. A woman named Kaci Murley helped organize the tnAchieves program, which offered scholarships worth up to $3,000 to help high school students attend community colleges and trade schools. She said nearly every high school student who applied won a scholarship automatically. But they had to attend meetings. The problem: the students just didn’t come. As of January 2013, roughly half the students across the city who had applied had already forfeited their chance. At Kingsbury, 82 had applied, and 11 came to the mandatory meeting.

And now at the Middle Tennessee State recruiting event, about 20 minutes remained before 7:00 p.m., when the big blue traveling show would pack up and leave. The recruiter who had put his arm around Isaias after the meeting at Kingsbury stood near the door, ready to greet anyone who came through. The tables were still full of food. The leader of the audio recording program waited, ready to talk. The university president hadn’t come after all, but several other high-level officials had.

And Isaias was still nowhere to be seen.