January 2013:

Four months before graduation

A WHITE FROST CLUNG to the boxlike brick houses across the street from the school on January 15, and the weather report predicted sleet and freezing rain. The school system might cancel classes and send everyone home.

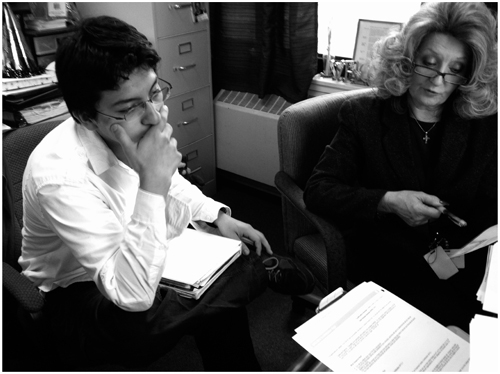

But Isaias still arrived at his financial aid appointment at Patricia Henderson’s office, a little glassed-in box inside a larger room by the school’s front door. Ms. Henderson was 57, a white grandmother of five, and she had grown up in Waukegan, Illinois, a Chicago suburb. She wore her hair in a silver-blond mane that stuck out several inches from the sides of her head.

For the next several months, Ms. Henderson would hold one-on-one meetings like this with Kingsbury students, a process that could win the kids tens of thousands of dollars. The federal Pell Grant for low-income students was worth up to $5,550 that year—free money that students didn’t have to pay back—and it was just one of several federal aid programs available.

Isaias took a seat, and Ms. Henderson asked, “What is your assigned social?”

“Here’s what I got,” Isaias said, opening a binder and handing her a stiff piece of paper. “I actually got this in the mail yesterday.”

She inspected the blue Social Security card, still attached to a larger sheet that bore Isaias’ address. The card was stamped with the words “VALID FOR WORK ONLY WITH DHS AUTHORIZATION.”

Isaias’ application to the Deferred Action program had succeeded. Until the previous year, it would have been all but impossible for someone like Isaias to receive a real Social Security card and the right to work legally within the United States. Now he had both the Social Security card and a two-year renewable work permit. And later that year, these documents enabled him to take a road test and get a Tennessee driver’s license, valid as long as the work permit was. His days of driving without a license would end.

In the cubicle, Ms. Henderson told Isaias that she doubted he would qualify for federal financial aid. But she didn’t fully understand the president’s new immigration program. “Let’s just do it all, like you’re gonna get it. And let’s just see what happens.” Her red-manicured fingernails clicked against the keys.

(Photo by Daniel Connolly)

They worked through the lengthy process of typing information about Isaias’ family members and their income. Ms. Henderson said that because Isaias’ parents didn’t have Social Security numbers, his father would have to sign a form and mail it to an address in Mt. Vernon, Illinois.

“Man, this is complicated!” Isaias said. Ms. Henderson laughed heartily. Then the counselor pulled up a page on a federal website that showed a picture of a smiling Hispanic man with a crew cut. Isaias read aloud. “Many non-U.S. Citizens qualify for federal student aid. If you fall in one of the categories below, you are considered an ‘eligible non-citizen.’” He continued reading. “U.S. national. No. U.S. permanent resident. No. You have an arrival-departure record I-94. I don’t. Victims of human trafficking … If you are a battered immigrant qualified alien…”

Ms. Henderson interjected: “I haven’t seen any of your bruises.” She laughed and Isaias laughed, too, quickly. Isaias kept reading and reached the end of the list. The website didn’t mention Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the president’s new program.

“See?” Ms. Henderson said.

“Wow. That’s some crap,” said Isaias. He leaned back in the chair, one hand behind his head, the same gesture he had used when he was losing at Knowledge Bowl.

They completed the electronic FAFSA form, and a message appeared on the laptop screen. “Because you are neither a citizen nor eligible non-citizen, you are not eligible for federal student aid.”

Ms. Henderson told Isaias he should talk with his immigration lawyer. “What do you have to do to become a permanent resident?” Isaias didn’t respond, but under the law, he could do little. The Deferred Action program offered the two-year renewable work permit and nothing more.

Ms. Henderson quickly gave Isaias another assignment. “My next step for you is to call MTSU in the next couple of days and say, ‘Okay, I did my financial aid, I’m not qualifying because I just got my assigned Social Security number. And so, what do I do next? I need money to go to your school and I want to go to your school.’”

“Okay,” Isaias said.

They were almost done. “You’re just a prime example of a great student,” she said. “That’s all there is to it. I just wish I had better news for you.” He thanked her, and she wrapped him in a big hug. “Oh, Isaias. You’re welcome, sweetie.”

Isaias had expected bad news. But he felt a bit disappointed to hear it out loud.

* * *

That same week, Isaias and Magaly went to Jacklyn Martin’s classroom after school to help set up the next month’s black history program and organize a performance of the school play Trifles, a murder mystery.

Afterward, in the upstairs hallway, Isaias opened his Knowledge Bowl satchel and showed me the letters he’d just received in the mail. One letter began, “Congratulations and Welcome to MTSU, Isaias!” He’d been granted “honors admission” status, and the university had sent along information about required immunizations.

The University of Memphis had sent a similar acceptance letter, along with a certificate that read “Eligible for Scholarship!” in big letters. No details, but the message cheered Isaias. For the past few weeks, since New Year’s, he’d been “all hazy” about college. He couldn’t say why.

Later in the school year, he told me he didn’t have a calendar to keep track of deadlines. “I tried putting stuff on my phone, but I don’t like my phone either. So I just try to keep it in my head, but I forget a lot. But it works.”

Now, in the hallway, he said, “For one point, I had even completely gotten college out of my mind. I was just going through life pretty happy.” The letters encouraged him to think about college again.

He said he wanted to go. “Even if I try to get it out of my mind, it would be really cool to go to college. If I can get it paid for, I’ll fly through.”

I asked Magaly what she thought. “I’m happy I guess?” She paused. “I mean, I don’t know. I can’t rule his world. Like ‘go to college for me.’ I’m fine with it.”

I said I was just curious. “It’s a weird question,” she said.

I left them and went downstairs, where I ran into a group of people gathered near the front door of the school. Something was going on. “Estevon said it was seven shots that he heard,” Patricia Henderson said.

I walked outside and saw a commotion down North Graham Street to my right, by the Streets Ministries community center. A group of police cars had pulled to the curb, a man sat in the back of a cruiser, and an adult administrator from Streets was arguing with an angry girl.

Confusion reigned. I quickly learned the basics: a fight had escalated and a man who apparently wasn’t a Kingsbury student had started firing wildly but hadn’t hit anyone. Police would arrest and charge several people. I saw Estevon in the crowd, and he confirmed he’d been close to the shooting. “Just gunshots and everything. I didn’t run. I just walked over there.” Dressed in a black hooded sweatshirt and with a wisp of mustache and goatee, Estevon seemed unaffected. “I’m not surprised. I just don’t care, really.”

Another person who’d been close to the gunfire was Raul Delgado, a senior and a student leader. Raul was born in Nicaragua, and his black mustache, beard and strong eyebrows gave him an intense look, like Che Guevara. He was so comfortable approaching adults as equals that one time that year he came to a faculty meeting and gave an update on the international club he led. Raul said he had seen the shooter but hadn’t been directly in the line of fire, so he didn’t worry. “I mean, it’s kind of normal, too.”

Memphis has long been one of the most violent cities in the country. Shootings are so common that when I became a newspaper intern in 2001, editors coached me to write about gunfire only if someone died, and then usually very briefly. A nonfatal shooting only counted in unusual circumstances—if a child was shot, for instance, or if the number of people wounded was unusually high. Five people with nonfatal gunshot wounds would merit a mention, two people shot might not.

The city’s crime rate was actually dropping, and the school building itself was usually quite safe, aside from fistfights. But the gunfire illustrated the day-to-day perils that Kingsbury students like Estevon lived with. It was a long way from here to Carnegie Mellon.

* * *

February 2013:

Three months before graduation

The Baltimore Ravens beat the San Francisco 49ers in the Super Bowl. Afterward, Patricia Henderson bought a cake with plastic football decorations for a marked-down price of $6.99.

She transformed a school conference room into something that looked like a children’s birthday party, decorating the table with conical hats, little kazoo trumpets, and noisemakers that unrolled with a pfft! She hung signs on the wall that said “HAPPY NEW YEAR.” That was a bit of a stretch because the date was February 4, but it was, in fact, the first meeting that year for the group of high-achieving kids she called the Super All-Stars. To join, the students had to have grade point averages of at least 3.75. She organized parties and took them on fun trips—in November, for instance, they’d gone to see a local appearance by Blue Man Group, the troupe of actors and musicians who performed mutely in blue makeup.

Classes had ended for the day, and students began to arrive. Cousins Tommy Nguyen and Tri Nguyen put on the conical hats, which made them look like wizards.

Leonard Duarte walked in next. A U.S. citizen child of Mexican immigrants, Leonard was tall, wore glasses and held a high rank within the school’s JROTC program, and he was likely to graduate as valedictorian. In AP Chemistry class, he rarely spoke, and in slow moments he sometimes drew fantastical creatures on graph paper, all wings and horns and sharp edges. Now he asked, “What’s with the hats?”

Ms. Henderson created a party atmosphere for a serious purpose. These students were scheduled to graduate in mid-May, in just over three months, and this meeting was a crucial chance to check their progress toward college.

Each student gave a report on college applications. Isaias said he’d applied to the University of Memphis, Middle Tennessee State University, and Christian Brothers. “And what is your number-one school that you really want to go to?” Ms. Henderson asked.

“I think I’m going to actually end up going to U of M,” he said.

“Over MTSU.”

“Mmm-hmm.”

“Can you share with us why?”

“I can be close to my family. It’s cheaper. They have sent me more money in scholarships. And it’s not that bad. I mean, it was my second choice.”

Isaias and his brother Dennis had talked about it in snippets the previous week while watching TV and playing video games. Money was a big factor. Academic scholarship letters had arrived: MTSU had offered Isaias $4,000 per year. The U of M offered $5,500 per year.

But unauthorized immigrant students like Isaias would pay the out-of-state tuition rate, which at each college totaled more than $20,000 per year. So it looked like the scholarships wouldn’t be enough.

However, David Schmidt from Middle Tennessee State had sent an e-mail with more good news:

Dear Isaias:

Good Morning. Because you have your Social Security card and work permit you are now eligible for in-state tuition. This is something new which we just enacted at MTSU. I verified this last night with our domestic admission representative.

Isaias hadn’t asked the University of Memphis, but that institution was controlled by the same state board as MTSU; assuming that the U of M also granted him in-state tuition, with the scholarship, Isaias could pay less than $2,000 per year. And he could live at home.

Tri, Tommy, and Jason Doan said they planned to go to the University of Memphis, too. Then Ms. Henderson turned to Estevon.

“All right, Estevon, what is yours?”

“UT-Knoxville for free.”

Tri interrupted. “You’re going to UT-Knox?!”

“Yeah.”

“What happened to Carnegie?”

“That’s if I can get enough financial aid from them.”

Ms. Henderson interjected. “Tell them how much Carnegie Mellon is.”

Estevon said tuition was $45,000 per year. The university listed a slightly higher price on its website, nearly $47,000 per year, with fees, room, board, books and other costs bringing the total price to $62,000.

Even with a big financial aid package, Estevon said he’d have to take out loans, and he didn’t want to. Tri said he should. “But you’re going to such a good school! You’re gonna pay it off in no time!”

“It doesn’t matter,” Estevon said flatly. Estevon wanted to go to graduate school without the burden of student loans.

“Yeah, he has a point there,” Tommy said. Isaias said he would do what Estevon was doing.

When college prices rose to the astronomical Carnegie Mellon levels, even a financial aid package that covered most of the costs could leave a family with thousands of dollars to pay. Patricia Henderson knew that for a poor family, even $1,000 represented a big burden.

She questioned whether students could land a job that paid well enough to cover college loan payments on top of all their other expenses, like a car payment and rent, and she strongly recommended that students avoid debt. As she saw it, if Estevon could avoid loans by choosing UT-Knoxville, he should do it.

She encouraged students with strong grades and test scores to apply to the nation’s best universities. But for other students, especially those who would otherwise have to go into debt, she recommended low-cost schools like Southwest Tennessee Community College.

Southwest served as the default option for many Kingsbury students. It cost relatively little and admitted everyone who met minimum standards. But it came with a downside: almost no one graduated.

The completion rate for students who’d started in the fall of 2010 stood at just 6 percent, worse than any other public college or university in the state.1 Another 9 percent managed to transfer to other schools. Many freshman students arrived at Southwest unprepared for college work and had to take remedial classes. They were often the first in their families to go to college; they faced financial problems, lacked support, and dropped out.

The state government had passed a new law that tied funding to students’ progress—if students didn’t earn credits and advance toward completion, the college would lose money. Because of the new criteria and several other factors, Southwest’s state funding would drop from $38 million in 2008–2009 to $25 million in 2014–2015.

Southwest staffers were trying to raise the graduation rate. In 2015, I spoke with Dr. Cynthia Calhoun, an executive in charge of those efforts, and she described several recent changes. Among them: The college had created an “early alert” system in which professors reported students who were absent or tardy so they could be referred to tutoring or other interventions. A new center on campus offered individual coaching as well as workshops on subjects such as time management and math anxiety. New rules required students to see an advisor before they registered for classes—previously, talks with an advisor were recommended, but not mandatory.

The graduation rate at Middle Tennessee State was better, but still not stellar: 46 percent within six years. At the University of Memphis, it was 43 percent. Rhodes College, perhaps the best private college in the area, had a graduation rate of 81 percent.2

Wasn’t Ms. Henderson concerned about the low graduation rate at Southwest? Not really. As she saw it, the low graduation rate reflected not the quality of the school, but rather the poor preparation of the incoming students. She said the Memphis City Schools tended to push kids to graduation regardless of their true skill levels, and unlike schools such as Kingsbury, the community college wouldn’t give students countless chances to turn in work they should have finished weeks earlier. If they failed, they failed, and for some students, this came as a rude shock.

For Ms. Henderson, college was what the students made it. Students could go to Southwest, become discouraged, and fail. Or they could start hustling, taking advantage of supports like free tutoring.

Isaias and many of Kingsbury’s other leading students aimed for the University of Memphis, which more privileged kids would consider a safety school at best.

Of course, hardly anyone at Kingsbury even used terms like “safety school” and “reach school,” since almost no students played the privileged youth’s game of applying to selective colleges. In the senior class, Estevon Odria was essentially the only one who’d tried it, and now he appeared to be scaling back his ambitions.

The National Bureau of Economic Research studied the college choices of kids much like the ones at the “New Year’s” party at Kingsbury: students with low incomes and high test scores. They concluded that the vast majority of these students didn’t apply to any selective colleges.3

The researchers called this a costly error. Selective colleges wanted qualified low-income students who could add diversity to mostly white campuses; the colleges often gave them generous financial aid, and the students tended to graduate.

Did it really matter whether students went to a selective college like Carnegie Mellon or to a school like Southwest Tennessee Community College? According to researchers at Georgetown University, the answer was yes.

“If I’m the parent of a kid who’s at risk of not graduating, I want them to go to the most selective college possible,” said Anthony P. Carnevale, director of Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce. “Because it’s most likely that they’ll get a lot of parenting at the college. And the college will not let them leave.”

Selective colleges competed with other institutions to show an impressive graduation rate, and administrators didn’t want students to drop out and disappoint parents paying huge sums for tuition, Mr. Carnevale said. Selective colleges typically spent more money on their students than less-selective schools and offered much more tutoring, counseling and other support. If students failed to come to class, someone would likely notice and intervene. An array of on-campus activities built a strong culture that likewise attached students to school.

A student with an SAT score that was average or above average had a high probability of graduating from one of the nation’s 468 most selective colleges, Mr. Carnevale concluded. If the same student chose an open-access college like Southwest that admitted everyone, the odds of completion dropped dramatically. For students who had scored an above-average 1,200 on the SAT, for instance, the graduation rates were 87 percent at selective colleges—at open-access colleges they were only 58 percent.4

So why didn’t more students from minority and low-income backgrounds apply to selective colleges?

The National Bureau of Economic Research authors pointed to several possible reasons. One was lack of connections—the students were unlikely to meet a teacher or older student who had attended a selective college. The recruiting tactics of selective colleges played a role, too: they often sent recruiters to high-quality public schools that were known for educating large numbers of high-achieving low-income students, and the recruiters often chose to look for these students close to the college campus. Recruiters might never meet the bright but impoverished students scattered throughout the nation’s other high schools in cities like Memphis.

Mr. Carnevale offered another reason low-income kids would pick less prestigious schools: they felt comfortable there. The white upper-middle-class environment at selective colleges often made minority kids from low-income backgrounds feel out of place. In the long run, though, a minority student who could push through the difficult transition to a selective college would likely succeed, Mr. Carnevale and a fellow researcher wrote in 2013: “African-Americans and Hispanics clearly benefit by going to selective institutions even when their test scores are substantially below the institutional averages at those schools.” The Georgetown researchers concluded that each year, thousands of African-American and Hispanic kids who could have graduated from college didn’t do so.

That said, not every selective college was prepared to give low-income students a break.

Universities had begun adjusting financial aid packages and giving low-income students worse deals than they used to, according to a 2014 analysis by The Dallas Morning News. The universities were instead spending money on “merit” scholarships that would draw academically strong students from middle- and high-income families who could pay part of the tuition bill and help the universities’ finances.5

So the Georgetown experts said that going to a selective college was generally a good idea for low-income students, but The Dallas Morning News analysis suggested that they might not be able to afford to go—or they might have to borrow money to do it.

By 2015, more than 41 million Americans owed more than $1.2 trillion in student loan debt. The median student debt burden rose from about $13,000 in 2007 to nearly $20,000 in 2014.6

One in four borrowers was either behind on payments or had defaulted, a government agency estimated. Those who fell behind could face unpleasant surprises: aggressive phone calls, garnished wages, or a federal tax refund that never showed up because a debt collector intercepted it, said Chad Van Horn, an attorney focusing on bankruptcy and debt resettlement in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. All of this led to stressful lives. “People never think about the psychological effect of carrying debt,” he said.

The national student debt picture looked bleak, but a Brookings Institution review of the data made some interesting findings. Many of the people who defaulted on student loans had gone to for-profit colleges and other nonselective institutions. Graduates of these schools often had weak educational outcomes and had trouble finding jobs. “In contrast, most borrowers at four-year public and private non-profit institutions had relatively low rates of default, solid earnings, and steady employment rates,” the Brookings report said.7

Mr. Carnevale, the Georgetown expert, said that many students made the mistake of taking out too many loans. But disadvantaged students often made the opposite mistake: taking out too few loans and instead paying for school by working long hours, which made them less likely to graduate.

Because earnings varied greatly by major, taking out loans could very well make sense, particularly for a high-paying field. “If you’re going to be an engineer, you can afford the loans,” he said.

Though Carnegie Mellon was certainly a far better choice than Southwest Tennessee Community College, the choice was less clear-cut between Carnegie Mellon and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, a state flagship school.

An engineering major who graduated from either school would be likely to have good earnings prospects, Carnevale said, but Carnegie Mellon probably had an edge in prestige, better hiring connections to large companies, more per-student spending, higher placement in graduate school, and a higher graduation rate. (At UT, 66 percent of students who began in fall 2006 graduated within six years compared to 87 percent at Carnegie Mellon.)

Someone who planned to go to graduate school might save money by doing the undergraduate years at UT and spending heavily on an expensive graduate program later, Mr. Carnevale said. “If you’re just going to get a BA, all things being equal, go to Carnegie Mellon.”

* * *

At the New Year’s party, Ms. Henderson said the students needed to think about the long-term financial consequences of their choices. “You’ve got to start thinking in these terms, though, do you see what I’m saying?”

One of the students made a flippant comment: “So should I buy a stripper now … or later and pay her back?”

“Oh God, help me,” Ms. Henderson said.

The University of Memphis wasn’t a top school, but barring disasters, Isaias appeared set to enroll at a college, something no one in his immediate family had done. His path to this moment had not been easy. He had earned good grades in school for years and scored unusually well on his standardized tests. To get an ID, he drove to the closest Mexican consulate, two hours away in Little Rock, Arkansas. He’d gone through the time-consuming and expensive process of applying for the Deferred Action program and getting a Social Security card.

Most importantly, he had talked of quitting but hadn’t.

After the meeting between Patricia Henderson and the top students, I wrote a note to my family and friends: “None of this is quite settled yet, but things are looking better for Isaias than they have in months.”

As I would soon learn, I was wrong. Isaias’ understanding of his own situation was wrong, too. Even the university officials who had spoken with Isaias were wrong. Massive barriers still stood between Isaias and a college education. Despite everything that university officials had said, the State of Tennessee still viewed Isaias as an unauthorized immigrant who could not qualify for in-state tuition or most scholarships. His path to college would be far, far harder than anyone expected.

And even before Isaias learned these harsh facts, his old doubts returned, and he told people he wasn’t going to college.

* * *

Mariana Hernandez and Adam Truong broke up, and Adam took it hard. On a college trip in February, Adam looked so depressed that Patricia Henderson put an arm around him and asked, “What’s wrong with you today?”

They were on the campus of Victory University, a small college near the high school. In the auditorium, the tour guide said a young Elvis Presley had attended services there, back when the building was a church.

Adam and the others were shown the modest biology lab and the small, cramped library, its shelves stocked with titles like The Interpreter’s Bible and All the Children of the Bible. A student newspaper, Voice of Virtue, carried stories about a book written by one of the university’s biblical scholars as well as the new dormitories, the startup honors program and a brand-new student government.

Victory University had once been Crichton College, a nonprofit Christian liberal arts school that was founded in the 1940s. Crichton ran into financial trouble, and in February 2009, a for-profit company called SignificantPsychology LLC announced that it had bought the institution. The company would later change the school’s name to Victory.

The man behind the deal was Michael Clifford, a well-known figure within the world of for-profit colleges. He was featured in the 2010 PBS Frontline documentary “College, Inc.” A musician and former drug user who had never gone to college, Mr. Clifford said his life changed when he became a born-again Christian. He later got involved in higher education—more specifically, buying colleges.

“From his headquarters in the sleepy beach community of Del Mar, California, Clifford is building an empire,” the documentary’s narrator said. “He invests in failing universities and injects them with large amounts of capital. When they go public, he can make a bundle of money in the process.”

For-profit schools had operated in the United States for decades. Most were local businesses that offered basic career training, said Kevin Kinser, a professor at the University at Albany and an expert on the industry.

But in Arizona, the University of Phoenix created a new model when it launched in the 1970s: a publicly traded, highly visible company that spread nationwide and offered degrees that competed directly with other universities. In 1992, the government banned these schools from paying their recruiters based on the number of students they brought in. The government feared that the colleges were recruiting unqualified students who couldn’t graduate and couldn’t pay back federal loans.

In 2002, the administration of George W. Bush loosened the rules, allowing colleges to give recruiters bonus payments once again, under what were known as “safe harbor” provisions. Recruiters could get extra pay twice a year as long as that pay was not based solely on the number of students they brought in. Student counts rose fast. Across the country, for-profit institutions enrolled more than 2 million people in 2010, 10 percent of the total college-going population and more than eight times the number they had enrolled in 1995.

But the Frontline documentary laid out troubling facts: Students at for-profit universities dropped out at higher rates than did students at other universities.8 Graduates from these schools usually carried far more debt than other graduates, and they were more likely to default.9 In some cases, they struggled to repay debts because they’d gone through a bad college program, and no one would hire them. Victory University fit the bigger for-profit pattern of low graduation rates and dependence on federal student loans. In the 2011–2012 fiscal year, for instance, 100 percent of incoming freshmen received federal student loans, and the graduation rate was only 13 percent. In June 2012, shortly before Isaias began his senior year, an accreditation agency put Victory on warning status. The reason: financial instability. The university needed injections of outside cash to stay alive, the agency wrote. “That sponsorship to date appears to be $8.6 million, and the institution acknowledges that more capital infusion will be needed,” the letter said. “Achievement of enrollment goals is yet to materialize.” The university’s financial problems weren’t widely known in Memphis. When the Kingsbury students visited Victory University that day in February, there was little—other than the obvious limitations of the tiny campus—to suggest that it might not be a solid choice.

Neither Adam nor Mariana would enroll at Victory University. They would remain friends after the breakup, though they weren’t as close as they’d been before.

* * *

February also marked Black History Month. At Kingsbury, two students played leading roles in organizing the school’s cultural program: Isaias and Raul Delgado, both of whom were Hispanic. Isaias recognized this put them in an odd position. “I mean, we can’t pretend to know, since a lot of us are not African-American, we don’t know exactly what it is to be African-American,” he said at one organizational meeting. “But we should at least be respectful of it, be educational, and try to get a message out.” He argued that the students should set a serious tone in the cultural program to reflect the unfortunate elements of the black experience. “It hasn’t been as happy as others.”

Race relations at Kingsbury High weren’t always so understanding. In late January, someone smashed the windows of three vehicles in the school parking lot and stole a stereo and other items. As one Hispanic student cleaned up the glass, he angrily said what he’d do if he caught the thief. “I ain’t breaking that nigger’s window. I’m breaking that nigger’s arm.” He had no way of knowing the criminal’s color, but his assumption reflected broader tensions.

Outside the school, gang members frequently targeted Hispanic immigrants for robberies at gunpoint. Immigrants often carried cash, and robbers apparently believed that widespread illegal immigration status and lack of English made victims less likely to go to police. Many of the robbers were black.

Robberies of Hispanic immigrants became so common that by 2007, then–county prosecutor Bill Gibbons was trying to encourage unauthorized immigrants to testify by issuing crime victims a special card they could show if agents picked them up on immigration charges. After the financial crisis of 2007–2008, robberies against Hispanics dropped, perhaps because criminals no longer saw them as victims flush with cash. Still, the pattern of black criminals targeting Hispanic immigrants persisted on a smaller scale, and the robberies sometimes ended with victims shot dead. Some other immigrants responded with open racism. For their part, some African-Americans resented that employers at times favored Hispanic immigrants—this was particularly true in the warehouse sector, where the two groups vied for the same low-paid jobs.

Within the school, I never heard of racially motivated fights. Yet I noticed a pattern in the cafeteria sometimes: black students gathered at certain tables, while multiethnic groups of Hispanic, Asian and white students clustered around other tables.

A similar pattern emerged in the school’s honors and advanced placement classrooms: Hispanic, Asian and white students were more likely than African-Americans to take hard classes.

Consider chemistry, a course that was required for graduation. In the standard-level chemistry sections, black students made up 58 percent of the total. In honors, they made up 28 percent of students, and in advanced placement, the hardest level, only one of the 25 students was African-American. That year at Kingsbury, Isaias was one of five Hispanic students in the top ten, along with three students of Vietnamese descent; one of Middle Eastern origin, Ibrahim Elayan; and one African-American girl, Breanna Thomas, the Knowledge Bowl participant.

No white students cracked the top ten.

White and black families that had money were fleeing inner-city neighborhoods like the ones around Kingsbury, and the white and black families that remained in the area were often troubled. Whites at Kingsbury had very low graduation rates. Only 52 percent of white students graduated in the class before that of Isaias, compared to 64 percent of African-Americans and 62 percent of Hispanics. The principal remembered one white student at another school saying something like, “‘Oh man, y’all just think I’m some redneck from Nutbush,’” referring to a neighborhood near Kingsbury High. Mr. Fuller thought some white students in the area had internalized a negative view of themselves.

By contrast, I concluded that for immigrant families escaping third world poverty, the Kingsbury neighborhood represented a step up. The adults in these families had shown unusual ambition and risk-taking by leaving their home countries, and in many cases they passed on at least some of this drive to their children. And immigrant families were often stable. In Tennessee, Hispanic youths were more likely than African-Americans to come from two-parent families—64 percent compared to 75 percent for white children and 33 percent for black children.10

Despite occasional conflicts, in general, students of different backgrounds got along at Kingsbury. Raul Delgado said he’d been robbed by masked teenagers in tenth grade, and he believed they were African-American—he could see their hands and hear their voices. Yet he said he didn’t hold it against all black people. “Even if it was a white person I wouldn’t hold a grudge against them or anything, ’cause not all people are the same.”

The day of the black history assembly came, and late in the program, Isaias connected his smartphone to the sound board in the auditorium. As the black-and-white footage from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech rolled on the phone’s little screen, the audio boomed over the speakers.

Onstage, student Arzell Rodgers matched his lips and gestures to the words, stepping into the role of the man who had been shot dead in Memphis in 1968, at a time when Kingsbury High was still all white.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

Magaly stood beside Isaias at the sound board, and when the speech was over, she applauded, and Isaias lifted his hands in the air and did the same.

* * *

March 2013:

Two months before graduation

During a slow moment at school one rainy day, Adam Truong asked Daniel Nix if he knew where Isaias planned to go to college. Daniel gave a quick summary of Isaias’ thinking. “That man’s like ‘I’m going to college. No, I’m not going to college. I’m going to college. No, I’m not going to college.”

At the New Year’s party in February and in the days that followed, Isaias appeared almost certain to attend the University of Memphis. But he had never formally enrolled.

Patricia Henderson organized a small-scale college fair at the Streets Ministries community center near the school. She and other participants hoped to reach the numerous students who had made no plans for the future. Deadlines for selective schools had passed, but the less prestigious institutions that most Kingsbury students were targeting would still accept applications. Even so, the longer they waited, the more opportunities would pass them by. By early February, only about a third of the students had completed an application for federal student aid, even though Ms. Henderson was available to walk them through it.

“We’re doing everything but paying them to do what they need to do,” guidance counselor Brooke Loeffler said.

The keynote speaker for the college fair, Vincent Lee, took the stage at the main meeting room at Streets, addressing a crowd of students seated at round tables. A tall African-American man in a brown suit, Mr. Lee described how he had grown up with an alcoholic mother and gone on to become a manager with ServiceMaster Corporation. He warned the students that they must take advantage of the opportunities they had now.

“If you don’t prepare now, this world outside this school campus and outside of Streets Ministries don’t have love for you,” he said. “It really doesn’t.” As he spoke, some students at the round tables didn’t bother to turn and face him.

He wrapped up his speech. Ms. Henderson came to the stage next, calling out, “Good morning, everyone! Where are my ambassadors? I need them up here with me for just a moment.” The ambassadors were students who had finished their college applications and would help run the day’s program. Ms. Henderson had wanted Isaias to act as an ambassador. But when someone asked Isaias on her behalf, he said no.

Isaias knew the college event at Streets would mess up the whole day’s schedule, and juniors were taking the ACT, too, which added to the disruption. Screw that, he’d stay home. He spent most of the day watching movies.

Friends came by his house, and Isaias finally went to school in time for the seventh and last period of the day, Jinger Griner’s English class. He had to take the course to graduate, and he liked it. Isaias emerged from Ms. Griner’s classroom at the end of the school day and found Magaly waiting in the hall, beaming.

They walked to a hallway in another part of the school to practice for a competition called Canstruction in which they’d use food cans to build a sculpture. Isaias took the lead. “Our three rolls have to fit in this, this and this area,” he said, gesturing to a space on the floor. When the timed contest took place at the University of Memphis a few days later, the Kingsbury team would build a replica of a Japanese sushi meal. During this practice session, the students busily set about arranging cans of beans and tomatoes—black labels evoked the seaweed wrap around a sushi roll.

Isaias examined the pile of cans they created. “Not bad, actually,” he said. “Squint your eyes. Hopefully we get a guy with really bad vision.” Then a student came down the hall with a message for him. “Ms. Henderson wants to see you.”

Isaias hurried down the hall toward Ms. Henderson’s office.

“Isaias!” she said.

“I heard you wanted to see me?”

“I did. Tell me why when they asked you to be an ambassador today, you refused!” she said, her voice rising. “Tell me why you did that! I put your name down!”

She had gone out of her way for Isaias, building a relationship with him over a period of months, bringing him to cultural programs and parties and investing tedious hours in helping him with financial aid and college application paperwork. Now he’d rejected a request for help, and it had come from her.

“Oh, Ms. Henderson. I didn’t know that,” Isaias said. “I’m sorry. I … thing is, I just … I don’t know, like, I didn’t want to do it.”

“Why didn’t you want to do it? All these colleges were there.”

Even though Isaias had received offers of admission from universities, he still needed to finalize the details, especially financial aid, and Ms. Henderson was angry that he’d blown the chance to talk with people who could help.

“I know. I know,” Isaias responded. “I guess I didn’t think about that. Missed opportunities. I don’t know…”

He leaned on the doorway of her cubicle and continued. “I didn’t find it that interesting, that appealing. The whole idea of it. I felt like passing on it.”

He said he felt bad for disappointing her, and Ms. Henderson softened and said, “Well, if you would have known I put your name in, you probably would have done it.” She asked Isaias about his immigration status, and he said nothing had changed. Then she asked about his application to the University of Memphis.

“Honestly, I haven’t checked,” Isaias said. “Actually, can I tell you something? I don’t think I want to go to college, period. I don’t want to go to college at all.”

He began to say that people at school make you think that you have to go to college. Ms. Henderson cut him off, saying that not everyone has to go to college—some would be better off going to trade school.

Magaly arrived and joined Isaias outside Ms. Henderson’s cubicle, quietly leaning against him. The counselor continued. “What I’m telling you—you are so smart. You would do well at college.”

“I’m pretty sure I would.”

Ms. Henderson asked what he wanted to do. “Like seriously, what I really seriously want to do is music. I want to be a musician. I want to tour the country.”

“You want to be a musician? You do realize most of that is being at the right place at the right time.”

“I know.”

He explained what was going on in his life: the successful painting business, how his parents planned to move back to Mexico, that he and Dennis would stay in Memphis, and how they might have to raise nine-year-old Dustin on their own.

She asked how he felt about his parents leaving. “I’m actually kind of excited,” Isaias said. “Well, I guess not excited. But I’m eager to see myself, ’cause it’s such a change.” And he said he and Dennis were up to the challenge of caring for their little brother.

She asked what would happen if Dennis got hurt on the job. Isaias said he’d carry on the business himself.

Ms. Henderson said he needed to have a backup plan. “Whether it’s going to school, whether it’s getting married. You know. Say you marry Magaly and she said, ‘You know what? I don’t want to work. I want to have kids. Oh my God, now we don’t have two incomes coming in.’ You know what I’m saying?” She tried to make it sound hypothetical. “That was a scenario. That was a scenario!”

They laughed, but the marriage scenario didn’t seem so far-fetched. Isaias loved Magaly and wasn’t self-conscious about showing it. The teenagers matched one another in brainpower, personality and interests, and it was easy to imagine them staying together for a long time.

Ms. Henderson asked if he saw his immigration status as a stumbling block. Isaias said no, he’d learned from his father’s example. “No matter what, you’re gonna make it. You’re not gonna let yourself go hungry.”

Sometime in the days that followed, Ms. Henderson told Isaias she’d like to see him go to college. She recalled saying, “I don’t want to say you’d be wasting your brain on painting or roofing, but I would love to see you become an engineer. Because you’re so smart. There’s no telling where that would take you.” She didn’t mention this that afternoon in her office, though. She said she might want Isaias and his family to do some work at her home and she mentioned that she might take the Super All-Stars to an outdoor performance of Hamlet. Isaias was overjoyed.

(Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht/The Commercial Appeal)

“I love Shakespeare so much! I’ve only read Macbeth but that just gets you hooked. That would be crazy!” Then he left to pick up his little brother.

* * *

Isaias’ sense of obligation to care for Dustin reflected a broader sense of duty to family that was common among children of immigrants. Researchers with the Pew Hispanic Center interviewed hundreds of young Hispanics for a 2009 report.11 Nearly three-quarters of Hispanic youths who cut off their education before college cited financial pressure to support a family. About half cited poor English skills, and about four in ten said that they disliked school or believed they didn’t need more education for the careers they intended to pursue.

Even as Isaias professed a lack of interest in college, he continued to pursue intellectual activities in the weeks that followed. With paint specks on his glasses from work, Isaias, alongside Magaly and other students, built the sushi sculpture out of food cans at the competition, and they traveled to an out-of-town robotics competition, too.

People who knew Isaias began to speculate about his thinking. Had his immigration status made him give up on college? He told me that unlike some unauthorized immigrant students, he’d long known about his status. “I’d always had this idea that I’m not quite as privileged as other people, like I’m a little less. As a child I did.”

When he was younger, it made him think he couldn’t do anything. He’d see people buying lottery tickets and think he couldn’t do that. He said perhaps some remnant of that young idea had stayed with him and impacted the way he saw college.

“It probably does. But not really. Like, my ultimate decision, no.”

I caught up with him one April morning as he walked into the school, and I checked his understanding of the cost of college. He said yes, he believed the U of M would cost him about $2,000 per year.

“It sounds about right. That’s what I remember. I would really need very little money for this. I could work in the summer and I would get about $2,000.”

We proceeded into the noisy front hallway. “I’ve always known inside of me, kind of this whole plan for my life, and college was just never part of it. The longer I stay in school, the more my mind gets corrupted.” He’d talked about this earlier, how the culture presented college as part of a normal life and how it influenced him. Now, at his locker, he said he didn’t agree with that idea. “If you know, or think you know enough to get by without college, you don’t need to go and waste your money—or your time, which is even worse. Four years of nothing. I don’t know. Time is really valuable to me.”

“How would you rather spend your time?” I asked.

“Anything but college would be more productive.”

Wouldn’t he miss intellectual things?

He said he might—he was already missing math and would like to dive into a calculus book. If he ever went to college, he’d study something fun. “Not college because I have to, but because I want to.”

Around the same time, I asked Dennis what he’d heard about Isaias’ college plans. Dennis said Isaias hadn’t said much and that when their parents wanted to know what Isaias was thinking, they asked Dennis what he knew. Cristina later explained her reluctance to question Isaias on the subject. “As a mother, you want to get involved, but your children rebel. They tell you not to interfere in their lives.”

Dennis figured Isaias would let the family know eventually. And he said Isaias was excited about joining the painting business and expanding it. Dennis wasn’t concerned. “Even if he doesn’t go to college, it wouldn’t be bad news.”

While Isaias worked closely with Patricia Henderson on his college applications, another college access organization had launched its efforts within Kingsbury High. It was called Abriendo Puertas, Spanish for “opening doors,” and it was the spearhead of an ambitious effort to boost achievement among the city’s Hispanics. It had backing from a large coalition of groups, including Memphis mayor A C Wharton.

The Indianapolis-based Lumina Foundation would pay $600,000 over four years to fund mentors. The social service organization Latino Memphis ran the program.

During the first semester of Isaias’ senior year, the new effort had barely gotten off the ground at Kingsbury, and an on-site director came and left quickly. During the spring, though, a former English teacher named Jennifer Alejo took over, and the project gained momentum. She was white and had taken her husband’s name when she married. Though her work focused on Hispanics, she offered college guidance to any student who wanted it, regardless of ethnicity. Ms. Alejo quickly became one of the leading experts within Kingsbury on the tricky task of getting unauthorized immigrant students to college.

By mid-April, she was hearing troubling news. Universities were telling her that students with immigration problems couldn’t qualify for in-state tuition even if they’d qualified for papers under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. I’d seen the messages that MTSU and the University of Memphis had sent Isaias, and they were impossible to misinterpret. Both universities offered Isaias significant scholarship money. An MTSU official had explicitly offered in-state tuition, and it was reasonable to think the University of Memphis would do the same.

To find out what was happening, I called the University of Memphis and arranged a meeting with the admissions director, Betty Huff. Within a few minutes of arriving in her office, I realized that everything that Isaias and I had understood was wrong.

She expressed sympathy for students with immigration problems but said a new state law tied her hands. In 2012, the Tennessee legislature had passed a law called the Eligibility Verification for Entitlements Act that aimed to block unauthorized immigrants from getting certain state benefits, including nonemergency health care.

I found out later that in August 2012, a state attorney had written a memo concluding that unauthorized immigrant students couldn’t get in-state tuition. A later legal memo concluded that Deferred Action students were not “lawfully present” and couldn’t qualify for any state scholarships. In the eyes of Tennessee, it meant nothing that Isaias had a Social Security card and a federal work permit. He was still in the country illegally.

“We have never told counselors or students that they were going to be eligible for in-state tuition or scholarships if they were DACA,” Ms. Huff said. Yes you did, I wanted to say. Isaias showed me the mail the university sent him. You even sent him a certificate that said “Eligible for scholarship!” But I didn’t mention his name, because I feared that I would ruin whatever chance he had.

If Isaias changed his mind and decided to go to the University of Memphis, he’d have to pay more than $20,000 per year. An impossible sum. Ms. Huff didn’t like the policy either. “What I don’t understand is the attitude that says they’re here, but we don’t want to educate them. They’re here. They’re not going anywhere.”

I came to realize that the officials at Middle Tennessee State University and the University of Memphis had genuinely wanted to help Isaias. Without meaning to, they had painted a far rosier picture of his prospects than they should have.

I didn’t tell Isaias what I had learned. At some point later—it’s unclear when—he found out from someone else. For the moment it looked like a moot point, since he’d already decided not to go.

The same day that I spoke with the U of M admissions director in the morning, I set out for the long drive across Tennessee to Chattanooga, where Isaias would participate in a vocational competition in audio recording through an organization called SkillsUSA. The next day, he ran around one of the hotels that hosted the conference, scrambling to put together an audio presentation along with fellow student Tyler Hunt, an African-American boy with dreadlocks. “I don’t think anyone’s as excited about their project as we are,” Isaias said. “Nobody,” Tyler responded. They’d win second place out of five teams.

On the night of Isaias’ arrival at the conference, he put on a red jacket and ate dinner in a big banquet hall. Students were coming to the front of the room and making speeches, dressed in the same red jackets.

I sat at a different table, looked at Isaias, and thought, “God help this kid.” For days, I had wanted to see Isaias change his mind and decide to go to college. Now the state universities seemed hopelessly out of reach.

Over the next few days, the depth of my sadness surprised me. As it turned out, someone else who knew Isaias felt the same way. She would do something about it.

* * *

For years, states had been fighting over the question of access to higher education for students like Isaias. As the immigration wave of the 1990s and 2000s swept into the country, the issue took on bigger dimensions. A 2009 report by the College Board described the situation: young people who were brought into the United States illegally or on visas that had expired often couldn’t receive in-state tuition, couldn’t receive federal financial aid, and finally and most importantly, couldn’t work legally in this country.12

People unfamiliar with immigration law sometimes assumed that these immigrants could fix their status by paying a visit to their local immigration office and filling out a few forms. Wrong. Both children and adults who had entered illegally or who had overstayed visas often lacked any legal route to regularize their status, ever. But the federal government usually didn’t enforce immigration law in the interior of the country—powerful businesses didn’t want agents to deport their workers—so these people could stay in the United States for years, in a sort of limbo.

Several states, notably Texas and California in 2001, had moved to open the doors to public universities to young people with immigration problems. “The vast majority of states, however, simply do not have any state policies with respect to undocumented immigrant students,” the 2009 College Board report said.

The report cited research that said an estimated 65,000 unauthorized immigrant students who had lived in the United States for five years or longer were graduating from high school, and that only an estimated 5 to 10 percent went to college. The College Board called for a federal solution, but it wasn’t forthcoming. A bill called the Dream Act would regularize their status, but it failed repeatedly in Congress.

In 2001, Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah became the first to introduce a bill with the Dream Act name. (A similar bill had been introduced in the House earlier that year.) The Senate bill wrote the word “dream” in capital letters that stood for “Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors.”

The original concept was simple: a young person with immigration problems who had spent years in the United States could earn legal status by going to college. Over time, the proposed requirements changed, but the general idea was the same: good kids with immigration problems could earn some sort of legal status.

The Dream Act concept was still new in August 2002 when The Denver Post ran an article about Jesus Apodaca, a 17-year-old who had been brought illegally from Mexico at age 12. He’d been accepted into the computer engineering program at the University of Colorado at Denver, but due to his immigration status, he would have to pay out-of-state tuition of nearly $7,000 per semester.13 The tone of the article was sympathetic. Yet for some people, the article inspired not sympathy, but red-hot anger.

“Recent media reports about illegal alien Jesus Apodaca, in which he complains about not being able to receive the benefits of legal aliens and citizens, just makes my blood boil,” Barbara Paulsen of Colorado Springs wrote in a letter to her local newspaper.14 “His attitude of just flouting our immigration laws and then whining because he can’t get financial aid for schooling is beyond belief … I hope Rep. Tom Tancredo continues his effort to see that this family does not benefit from its illegal activity.”

Congressman Tancredo was a vocal opponent of illegal immigration. When he read the article, he phoned immigration authorities and asked what they planned to do about it. (He later denied urging the authorities to deport the Apodacas.) Still, the spectacle became a national story. One of the most powerful men in America was taking on a 17-year-old who’d had no control over his parents’ choice to immigrate.

Political analyst James Carville and others attacked the congressman. Yet others saw him as a hero. The illegal immigration system was based on the fiction that the government was really trying to make these immigrants leave. Mr. Tancredo pointed out, loudly and repeatedly, that this wasn’t true, and he persisted even as many members of his own Republican Party turned against him.

Meanwhile, the publicity caused huge problems for the Apodaca family. Colorado journalist Helen Thorpe described them in her book Just Like Us: television trucks parked outside their home, reporters called incessantly, and people posted ugly things about them on the Internet.15

The Apodacas moved out and got an unlisted phone number. A private donor stepped forward and offered to pay Jesus’ tuition at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Then the donor pulled out, and Colorado governor Bill Owens asked one of his biggest donors to pay the tuition. Jesus Apodaca went to a different university. The red-hot anger cooled.

Over the years, I wrote many immigration stories that sparked the same furious reaction. Too often, angry readers aimed their vitriol at the powerless people caught in the middle: the immigrants. They asked why the immigrants broke the law, not why the government had created a system that allowed and encouraged the immigrants to break the law.

The Dream Act ultimately triggered hot emotion, not rational thought. For more than a decade, different versions of the bill failed in Congress, again and again, wilting like daffodils on a scorching day. The Deferred Action process that President Obama created in 2012 was a sort of “Dream Act Lite,” a temporary protected status that still fell short of real legal recognition.

But as important as immigration status was for students like Isaias, events that spring would convince me that another factor often played an even bigger role in their lives.