Late June 2013:

About one month after graduation

THE PLANE’S JET ENGINES droned. My seatmate, an elderly woman with glasses and a cane, asked me to help her fill out the visa entry card she’d give the officials in Mexico. “No sé escribir,” she said. I don’t know how to write.

More than a month had passed since Isaias graduated, and I was traveling to Santa Maria Asunción, the Ramos family’s hometown in Mexico. I wanted to learn about their lives there, and they readily agreed to help.

They showed me recent images of their old house on Google Street View: in their absence, the house had been partially converted into a tire shop. Mario and Cristina prepared gifts for me to deliver to their relatives, mostly t-shirts in plastic wrap with names written on scraps of paper pinned to them: a tan shirt for Blankita Chica, a pink one for Emma Celeste, and so on. They wrote out a list of names and addresses of their friends and family members and used Facebook and phone calls to let them know I was coming.

Isaias’ future remained uncertain. He had completed his application to Victory University but hadn’t heard back about the scholarship. One June night, Isaias said he’d thought about calling the staffers at Victory but didn’t look forward to it. If the university accepted him, great. If not, well, at least he had tried. He didn’t mention the idea of asking for help from Margot Aleman or his other supporters at school.

On the plane, the passenger who didn’t know how to write handed her passport to me, a stranger. I wrote her name, Ofelia Yanes, and her date of birth in 1946 on the immigration form. I gave the form back to her and she signed it, copying the signature from her passport.

She lived in Lubbock, Texas, cooked in a restaurant, and was visiting family members back home in Mexico. Her green card allowed her to travel, and she was about to meet a daughter she hadn’t seen in four years. She hadn’t made it beyond second grade in Mexico, but she told me some of her grandchildren were now enrolled in college.

Her story echoed the ones I had heard at Kingsbury and reminded me that what was happening there was happening across the country as the children of immigrants made their way in the world.

Mexico was still seeing horrific drug-related violence. Fortunately, I wouldn’t be traveling alone: I would work with Dominic Bracco II, a young American photographer now living in Mexico City who had already spent years working in some of the country’s roughest areas.

Cristina had far more serious worries than I did. Her sister Gregoria, who lived in Santa Maria Asunción, had terminal cancer. She hadn’t eaten solid food for days.

Gregoria was 51, a married mother of five whom Cristina would remember later as the older sister who moved away when Cristina was still young. When Gregoria had her babies, Cristina would go to her house and help with chores like washing dishes. At Christmas, Gregoria would come to the family’s old house on the hill with gifts of bread and fruit so her brothers and sisters would have something to enjoy for the holiday.

They’d talked on the phone recently, Gregoria wishing Cristina luck, then mentioning a child who wanted to come to the United States. Cristina didn’t want to get involved. And that was the last time they would ever speak.

Gregoria would die soon, and it would mark the second time that Cristina had lost a sister. A little over six years earlier, another one of Cristina’s sisters, Antonia, was walking or standing near the main road through town. A microbus had just dropped off passengers, and the bus driver pulled out in front of a large white truck cab that was traveling without a trailer. The truck driver swerved off the road to avoid hitting the microbus, but instead hit Antonia, killing her instantly.1

Antonia was in her early thirties and left three small children.

Cristina and Antonia had been so close as girls that they not only slept together, but shared all their clothes, even underwear. Antonia suffered from rashes and would tell Cristina “Scratch me!” and Cristina would, every night. They would shut themselves in a room and share all their secrets. They dreamed of growing up and becoming grandmothers together. Antonia cried when Cristina got married because she feared she would leave her.

And the last time Antonia talked with Cristina on the phone, she scolded her, saying she shouldn’t have gone to America. Then Antonia was dead, remembered by a white wooden cross at the side of the road.

Cristina hadn’t gone back for Antonia’s funeral. She hadn’t gone back when her father died in 2010. And now with Gregoria dying, she still made no plans to return. The brothers and sisters in Mexico couldn’t understand Cristina. “We’re dying,” they would say to her on the phone. “And you won’t come.”

“They think I’m made of stone,” Cristina said. Not so—she felt the same pain as the others did, but she didn’t let it show. That wouldn’t achieve anything.

If Cristina visited Mexico, she could find herself locked out of the United States forever and separated from her family in Memphis. Neither she nor Mario had a legal right to return to the United States; Dennis and Isaias with their Deferred Action paperwork could only get permission to leave and return under special circumstances.2 In addition, illegal border crossings had become even more risky. When the Ramos family crossed in 2003, about 9,800 Border Patrol agents were assigned to cover the southern border. A decade later, the number had nearly doubled, to 18,600. In the same time period, the Border Patrol’s budget rose to $3.5 billion, an increase of more than 80 percent, adjusted for inflation. The increase was even more dramatic if you compared 2013’s Border Patrol budget to that from 1990—adjusted for inflation, the United States was now spending more than seven times as much.3

For most of American history, border security had been weak. The Border Patrol wasn’t even created until 1924, and for decades afterward, Mexican migrants could easily cross back and forth over the lightly protected 2,000-mile-long border for seasonal jobs in agriculture.

But over the decades, the politics of immigration had prompted the federal government to pour more money into border security. When the public demanded that the government do something about illegal immigration, spending money on border security was what politicians did. Researchers concluded that between 2009 and 2014, more Mexicans left the United States than came in.4 But calls for greater border security continued. And of course, strengthening border security did nothing to address the fact that millions of unauthorized immigrants still lived and worked in America.

The country’s immigration enforcement was like a coconut: solid on the outside, milky and soft on the inside. Anyone who got through the tightening gauntlet of security at the border faced little chance of getting caught later.

This led to bizarre contrasts. Even as Congress threw hundreds of millions of dollars at border security, the Internal Revenue Service urged immigrants to file income tax returns even if they lived in the United States illegally—and many unauthorized immigrants filed the documents. Real estate professionals in Memphis happily made home loans to unauthorized immigrants. I spoke in 2006 with one of the people involved, Bob Byrd, chairman and CEO of a Memphis-area financial institution called the Bank of Bartlett.5

“We’re doing this because we think it’s right,” he said. “We’re doing this because it’s legal. And we’re doing this because it’s profitable.”

He said the Memphis-area bank had arranged between $12 million and $14 million in home loans for immigrants who lacked a Social Security number. Many immigrants in this category had come illegally or overstayed visas. None of the loan recipients had defaulted or been deported, and Mr. Byrd considered it unlikely that it would happen. “For the life of me, I can’t remember the report of a deportation in recent times.”

Years later, advocates for immigrants demanded that President Obama do more to help them and mocked him as the “deporter in chief,” pointing to statistics that showed rising numbers of expulsions. Yet when the Los Angeles Times looked closely at the deportation numbers in 2014, they found that most of the expulsions were for people arrested within 100 miles of the border—in general, people who had just recently crossed. Deportations of people in non-border areas, like the Ramos family in Memphis, had actually dropped from 237,941 in Obama’s first year to 133,551 in 2013, and most of those deported from the interior in 2013 came to the attention of immigration authorities after criminal convictions.6

“If you are a run-of-the-mill immigrant here illegally, your odds of getting deported are close to zero—it’s just highly unlikely to happen,” said John Sandweg, who had served as acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. He told the Los Angeles Times that even when immigration officials wanted to deport someone who had already settled in the country, doing so was “virtually impossible” because of a lengthy backlog in the immigration courts.

Unauthorized immigrants like Cristina were relatively secure if they stayed where they were—but if they tried to leave the United States, visit Mexico, and come back, they not only would have to contend with the Border Patrol and the sometimes deadly desert heat, they also would risk run-ins with the border zone’s many criminals. Some criminals simply preyed on migrants, robbing or raping them at gunpoint. Other criminals ran organized smuggling rings and worked for the migrants—supposedly.

Consider the story of Elizabeth Bonilla, the mother of Dante Bonilla, a classmate of Isaias’. In 2002, she’d come to America to work and to flee a violent relationship, leaving her three boys behind with her mother in Mexico. She met a better man in Memphis, had a baby girl with him, and when her mother was dying in 2007, she went back to Mexico to fetch the boys.

That left the problem of getting back across the border. She hired a smuggler named Victor, whom she remembered as a big man with light skin and an evil face. Elizabeth agreed to pay Victor a transport price of $1,700 per person, or $6,800 for all four of them.

Their first attempt to cross failed, and Victor helped them try again. They succeeded, but when they arrived in Houston, Victor demanded more money for his extra trouble: $1,000 apiece, or $4,000 total. Elizabeth didn’t have the money but said she could send it later. Then Victor brought her alone to an upper room in a house and put a pistol to her head.

She remembered him telling her that he wasn’t playing. That he would kill her, kill the children, put their bodies in bags, and no one would know what happened to her. That until she paid, he would keep the children.

Elizabeth cried, begged and tried to reason with him. If she couldn’t pay the debt for the crossing, how could she pay him to feed three boys?

She remembered him telling her that she was right. He would keep just one boy.

So she called her husband in Memphis, who drove to Houston to pick up Elizabeth and her two youngest sons. The oldest, 12-year-old Dante, stayed behind with Victor.

In Memphis, Elizabeth and her husband sold almost everything they owned, even their beds. They worked long hours, stopped paying rent and were evicted from an apartment. Elizabeth told her story to a Spanish-language radio host, who shared it on the air. Some listeners called her a bad mother. Others donated cash. All the while, Victor called her cell phone to spit curses and threats. She said he demanded the money and threatened to kill Dante, cut him into pieces and throw them away. He said if he saw any police around the house, he’d kill Dante immediately.

Elizabeth and her husband sent money for three months until, finally, Victor told Elizabeth to come alone to an Arkansas gas station. He was transporting a vanload of migrants and would deliver Dante.

He kept his word. The boy was alive and mostly well. Victor had kept him locked in his house for a while before giving him to a female associate, who in turn gave him to a family that treated him decently and let him play outside with their children. Dante said he was never abused, and he didn’t know about the death threats until he heard his mother tell the story years later.

Regret still ate at Elizabeth Bonilla. She said ignorance and fear stopped her from going to the authorities—in hindsight, a huge mistake. She carried a photo in her purse of what Dante looked like the day she got him back: haggard and in need of a haircut. It served as her personal reminder that she must never allow anything or anyone to hurt her children. She told them to seize all the opportunities they had in this country. Look at what it took to get them here.

Samuel P. Huntington wrote in 2009 that Mexican immigrants would not assimilate into America because Mexico was right next door. Mexican immigrants could remain in intimate contact with their families, friends and hometowns, unlike other immigrants whose home countries lay across wide oceans. They would retain their Mexican identity for a long time—perhaps for generations.7

But for people like Cristina, Mexico might as well have been as far away as Australia. And though Cristina still didn’t quite fit into American society—she didn’t speak English, for instance—each death in her family snipped a strand from the cord of connections that bound her to her home.

Cristina wanted papers: not full-blown citizenship, but something like a travel pass, a document that would let her cross the border and return. But the politics of the day made that impossible, so Cristina clung more tightly to her husband and sons in Memphis. They were all she had.

Millions of people lived in a similar predicament. As illegal immigration slowed down, unauthorized immigrants were more and more likely to have lived in the United States for many years. Demographers estimated that as of 2013, there were 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States, and that they had been there for a median of 13 years—meaning half had lived there longer. Many had U.S.-born children.8

* * *

Below us, the suburbs of Mexico City crawled into view, a vast expanse of buildings sprawling into the distance in the sun and smog. The plane descended. When the wheels finally touched the runway, Ofelia Yanes, my seatmate, said, “Dios mío. Gracias.” My God. Thank you.

At Mexican immigration, the official at the desk asked me one question. “¿De dónde llegas?” Where are you coming from? “De los Estados Unidos.” From the United States.

He stamped my passport and I was in. When I came back to America a few days later, the process proved nearly as easy. My U.S. passport served as a magic ticket.

I met Dominic, the photographer, for the first time at the Thrifty car rental spot by the massive international airport. Over the next few days, he showed an ability to quickly understand other people’s feelings, and I trusted him. He knew when to take a picture and when to put the camera away.

Dominic drove the rented vehicle through Mexico City traffic, a mess of fast-merging cars and trucks that went on for many frightening miles. In time, the city gave way to the countryside. We arrived at Tulancingo, a big town, and checked into our comfortable high-end hotel. Then we took the road out of town, past green hills, prickly pear cacti, agaves that looked like giant versions of an aloe vera plant you’d see on a windowsill, and a street vendor holding up a newspaper with the headline “Young Professional Woman Disappeared.” Shops had been constructed haphazardly along the main road, with unpaved gravel areas for parking.

Within minutes we arrived in Santa Maria Asunción, and along the main road we found the house that Mario and Cristina had left behind. Black tires were arranged in decorative patterns in the bare dirt of the front yard. A handwritten sign on a wall advertised oil changes, and dogs wandered about.

Various relatives had used the house since the Ramos family left. For the past five years it had been occupied by one of Cristina’s nieces, 36-year-old Maria Ines Castro Vargas, along with her husband and their two sons. Cristina had told them we were coming, but Maria Ines seemed nervous. Still, she let us in and showed us the house.

It was arranged around a central courtyard with trees and a big, rusty satellite dish that Maria Ines was using that day to dry her family’s jeans and socks. She said she’d been doing laundry when we arrived since the water ran only on Thursday and she had to use it when it became available. The roof was made of corrugated metal and held down with the weight of bricks and tires.

After we’d talked for a while, Maria Ines began to relax around us, the strangers. She pointed out a closed door that led to other rooms, explaining that the Ramos family had locked up their belongings inside. She didn’t have a key. But she mentioned that one of the walls to the closed area had begun to fall down, and her family had put up some blocks to replace it. Those blocks were loose. She said if we wanted, we could take some blocks out and look inside.

So, standing in the courtyard, we removed blocks in the storeroom wall until we created a hole big enough to peer through. I put my face close to the opening and felt cool air flow out, like from a cave. In the dim light I saw shapes: a toy truck, a top, a child’s dinosaur lying on its side, and two dusty bicycles. Isaias and Dennis had locked these toys away so they could play with them when they came back. Now it was far too late for that.

We put the blocks back in the wall, entombing the toys again.

* * *

Throughout our time in Santa Maria Asunción, I traded text messages with Isaias. He asked us to take a lot of photos of his old house, and we did. Because the Ramos family had paved the way for us and continued to make phone calls on our behalf from the United States, we found open doors everywhere. People served us delicious home-cooked meals of blue corn tacos, pozole with big pieces of hominy, and sweet flan.

I shared much of this with Isaias. That sounds great, he wrote in one text message. I am kind of envious haha. He asked when we would visit his uncle Alberto in Tepaltzingo, the village where his mother had grown up.

On the third day of our visit to Hidalgo state, we drove up a steep hill from Santa Maria Asunción to Cristina’s village.

We found Uncle Alberto’s house, and he greeted us in crisply pleated slacks and a white dress shirt. He was 50 and worked as a driver for a businessman in Mexico City, where he sometimes shared a tiny apartment with another man, but this house on the hill was his home. He introduced us to one of his sisters, Maria Candelaria, age 52, who had come to meet us.

We had already spent hours talking with friends and relatives of the Ramos family, but no one could remember anything like a going-away party before they emigrated to America. When I spoke with Uncle Alberto and Maria Candelaria, it became clear why: Mario and Cristina had vanished without saying goodbye.

Family members heard from Cristina a few days after she disappeared, when she called a caseta, a sort of public telephone that everyone in the village used. An employee from the caseta business found Cristina’s family in the village. Cristina arranged to call the caseta back at a specific time, and someone from her family came and took the call. And that was how her brothers and sisters learned she had left for America.

Cristina’s mother had died years earlier, but her father, Pedro Vargas, remained in Santa Maria Asunción. Until his last days, he had hoped his daughter and her family would come back, said Emma Celeste Castro Vargas, a 23-year-old cousin of Dennis and Isaias who’d often played with them when she was a girl.

She recalled that as her grandfather Pedro lay dying, his mind drifted back to his grandchildren Isaias and Dennis. She remembered him saying, “Did you talk to Chay and Denny? They’re running around outside and their mom’s going to scold them. Tell them to come in.”

She told him, “Isaias isn’t here anymore, Grandpa.” Pedro Vargas died in November 2010, having never seen his daughter and her children again.

All these years later, the sudden disappearance of Cristina and her husband and children still bothered Uncle Alberto. Perhaps Cristina didn’t owe it to her brothers and sisters to tell them she was leaving, but as he saw it, parents were a different story.

“Look, we’ve always acted independently,” Mario explained to me later. “We’ve almost always preferred not to share our plans with other people. I speak with her,” he said, indicating Cristina, “and we decide with the boys, with Dennis and Isaias and now Dustin. But we don’t tell other people.”

Cristina offered another reason for not saying goodbye. “Sometimes we’re afraid that when you talk, people won’t let you do things.”

“They won’t let you grow,” Mario added.

That day in Cristina’s village, Uncle Alberto and Maria Candelaria seemed torn between the impulse to criticize Cristina and the desire to forgive her and wish her well.

Maria Candelaria said, “Thinking it over, it was the best decision she could have made. At first I thought she’d acted very, very ungratefully or definitely didn’t feel anything for us, her family. But I reached the conclusion that she had left here at a young age,” she said, referring to Cristina’s time working in the big town during middle school. “And she didn’t feel the same way as the rest of us who were always together.” Maria Candelaria went on to talk about Antonia’s death when she was hit by the truck. “[Cristina] called and said, ‘I’m sorry. I’m with you.’ It’s not the same as living it, seeing it, to be so far away and say ‘I’m sorry.’”

Alberto spoke up. “My papa died and it was the same thing. She gives us a call, and that’s it.” Then Maria Candelaria swung back to the compassionate side. “She did it to seek other goals for her children, and what a good thing.” Uncle Alberto agreed. “Hopefully everything will go well for her, and on that side they’ll reach all the goals that they want. Because separating from a family, from your customs, from your roots—for nothing—I think it’s pretty difficult. But if they reach the objective for which they went, go ahead.”

They said Cristina still called and talked about coming back. Maria Candelaria said, “We’re losing hope of seeing her again … And my other sister’s going through agony right now. She won’t see her again. It could be any one of us tomorrow.”

Later we took a walk with Uncle Alberto, and he pointed to a house. He said the parents were simple workers, but they’d managed to send their children to college. One son had become an architect, a daughter had become a lawyer, and another son was studying civil engineering. His argument: you could improve your children’s lives without leaving home.

Uncle Alberto had a point. It seemed that everywhere we went in Santa Maria Asunción, we met young people who had gone to college. One of them was 22-year-old Blanca Vargas Martinez, nicknamed “Blankita Chica,” or “Blankita Hija,” who had recently graduated from a university with a degree in political science and public administration. She’d given up the low-paid job that Mario had mentioned at the Top 10 dinner in May and was now looking for another one.

Another married couple was sending their son named Ever to the university in Puebla with the funds from the cake business they’d built. It was a typical immigrant success story. Well, minus the part about immigrating.

In fact, the mother and cake entrepreneur Maria Isabel Vargas Tellez said the business was what had stopped her husband, Alejandro, from leaving the country to go earn money in America, unlike all three of her brothers, who had emigrated to the United States. So far, only one brother had come back.

And Ponchito, the childhood friend of Isaias, was now studying business administration at a university in Tulancingo, the big town. He’d grown up tall. His full name was Oscar Alfonso Barrios Silva, and many people had stopped using the diminutive “-ito” at the end of his nickname. With his glasses, Ponchito—or Poncho—looked as if he could be Isaias’ brother.

His family ran a large-scale fruit-selling business. He drove us around town in his parents’ van and showed us the places that had figured in the story of Isaias: the creek where they’d caught frogs, an old well, the elementary school playground where Isaias had told Ponchito he’d soon walk across the desert to America. We were talking in the center of town, and I showed Ponchito a cell phone video of Isaias practicing with Los Psychosis and chattering with his bandmates in English. “He’s almost unrecognizable,” Ponchito said. “He’s changed a lot.”

Opportunities for young people in Mexico had changed a lot, too. In 1970, when Mario was nine, nearly a third of all Mexicans over the age of 15 had only gone to preschool or kindergarten, or had never gone to school at all. More than a quarter of the population was illiterate. Underlying every story of young Mexican children dropping out of school was poverty: public schools charged various fees, and some parents didn’t pay or couldn’t pay.

By 2010, the situation had changed dramatically. Only 7 percent of the Mexican population had never gone to school. Fifty-eight percent of the population had completed at least ninth grade, and 17 percent had completed a university degree.9

Even the children of the lower middle class started going to universities, something that people like them had never done before, Jaime Ros, a leading Mexican economist, told me later.

He explained that Mexico’s economy had expanded rapidly until the early 1980s, when it entered long decades of slow growth. Even so, many Mexicans moved out of poverty and became educated. Why? Ros pointed to the “demographic bonus”—in other words, smaller families.

In the late 1960s, the average Mexican woman gave birth to seven children. But in the 1970s, the government began promoting contraception and smaller families, and birth rates fell dramatically. By 2013, Mexico’s birth rate had dropped to 2.2.10 “That’s allowed families also to spend more on their fewer children, allowing them to go through school and college more easily than in the past,” Mr. Ros said.

And more Mexicans began living in cities, a trend that went hand in hand with cosmopolitan thinking and smaller families. Concentrated populations also made it easier for the government to provide schooling.

Despite the growing middle class and success stories like those of the cake entrepreneurs, the research organization Coneval estimated that in 2012, nearly half of all Mexicans were still poor.11

We met 53-year-old Herlinda Sanchez Licona, who earned a living working at home, using her three sewing machines to stitch together the little pieces of fabric that made up a shirt. “It’s laborious. And it’s tiring,” she said. At busy times she’d stay up all night, which sometimes bothered her children, since three of them slept in the same room where she worked. She said the kids would sometimes complain: “Mama, turn out your light!” If she worked all day, she could finish ten shirts and earn the equivalent of roughly nine dollars.

Perhaps the biggest threat to Mexican society was what Rigo Navarro had described so graphically in his senior class presentation back in Memphis: drug corruption and crime, fueled by American users.

But as we walked with Uncle Alberto in the green hills around his town on the third day of our visit, we saw nothing but tranquil countryside. We spotted a horned toad lizard moving along the dusty soil, which was peppered with sharp black chunks of obsidian. I picked up several of the glassy stones as souvenirs. At a village church that evening, a priest said Mass and called for a special prayer for the health of Gregoria Vargas, the sister of Cristina.

The next morning, Gregoria died.

* * *

I had been planning for months to go to Mexico, and I hadn’t expected Gregoria to die while we were in town. Now Dominic and I found ourselves in a strange position: the friends and family members in Mexico naturally saw us almost as emissaries sent by the absent Cristina, who had helped arrange our visit.

We went with the family of Blankita Chica to buy flowers, which we brought to the wake. Uncle Alberto and the others received us graciously.

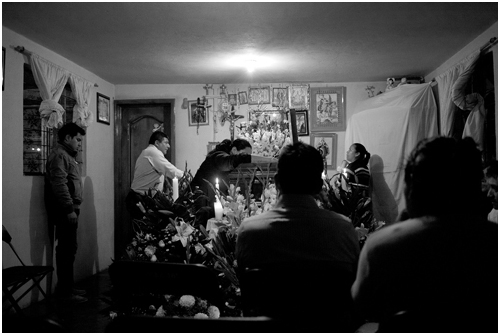

They held the wake in Gregoria’s own home, in a room whose walls were painted pink, and burning candles illuminated the mourners, the white flowers, and the casket with a panel of glass that offered a view of Gregoria’s face. A woman sang a slow hymn, and the mourners responded again and again with the chorus.

Rows of chairs had been set up before the casket, and people offered the visitors sweet bread, tamales wrapped in green leaves and hot sugared lemonade, the drink servers often going two by two, one with a pitcher, one with Styrofoam cups. Some mourners would stay all night. We paid our respects and left, the stars glowing bright above us.

Mourners, including Uncle Alberto (second from left), Gregoria’s daughter Claudia (at casket) and her other daughter, Paz (right), remember Gregoria at her wake. (Photo by Dominic Bracco II/Prime)

The next day, Gregoria’s friends and relatives crowded into the white adobe church at Santa Maria Asunción for her funeral. Many people had to wait outside, some holding umbrellas against the summer sun, and a teenaged boy fainted. A woman called “Alcohol!” and someone rubbed it onto his face to revive him. Dominic helped bring the teenager into the shade, where he recovered. The teenager had green sprigs of herbs tucked behind his ears, as did Blankita and many other mourners. Blankita said the herbs were ruda, or rue, as well as romero, or rosemary. She had a sprig tucked under her blouse, too. She said people believe that the dead person emits an energy of sadness or pain that other people don’t want to absorb, and that the herbs help block it. “It’s a protection we have.”

Later, the church bells rang, and a group of men carried out Gregoria’s maroon casket on their shoulders. Fireworks went off with loud bangs. A group of musicians dressed in black played and walked before the casket, huapangero-style with a sawing fiddle and a guitar, and the procession with its umbrellas turned right, toward the main highway, not far from where the truck had killed Antonia years earlier.

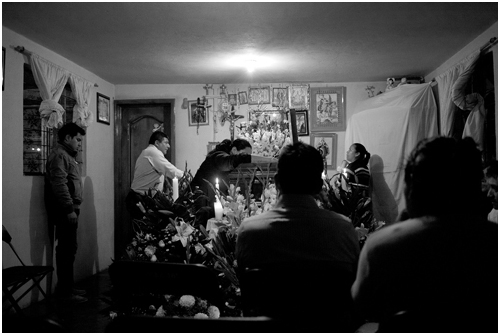

(Photo by Dominic Bracco II/Prime)

People had stopped their vehicles to block traffic, and we walked across the highway and past cornfields to the cemetery, a place with high weeds and tombs that rose into the air like small castles.

Hundreds of people crowded among the graves, some in jeans, some women in old-fashioned clothes that looked like aprons. A breeze blew the umbrellas. Again, people offered refreshments: cookies, chocolate, bottles of water and juice. Swallows flew overhead.

Workers in baseball caps shoveled dirt into the grave as the mourners watched. The musicians sang songs, including a popular tune from years earlier.

Como quisiera que tu vivieras … the chorus began.

How I wish you were alive.

Later, in a corner of the graveyard, Uncle Alberto asked me to tell Cristina to call him, and that afternoon I made a phone call to Memphis and relayed the message. I told her I was sorry for her loss, and I stated the obvious: that it was unfair that I could go to her sister’s burial and she couldn’t. She said “gracias” several times. Her voice sounded sad and strained.

Cristina went to work in Memphis that day, as she almost always did. “This country doesn’t forgive,” she said later, and laughed. Work itself could serve as a sort of therapy. So could talking with her husband. And life had made her strong, determined to move forward. She said if something was in her hands, if she could help, she would. If it was outside her control, she would let it go.

That night I thought about everything that had happened.

Was coming to America worth never seeing your sister again, even when she was dying of cancer? If Ponchito went to college in Mexico and Isaias didn’t do the same in America, what did that say about the choice to emigrate?

And what about the millions of people just like Mario and Cristina, people who had ignored the expiration date on their visas or crossed the border illegally? Was it wise for America to create a system that allowed these people to live in the United States for years, but with only limited rights? And was it wise for society to pay little attention to the particular needs of the immigrants’ children?

Was any of this a good idea?

It was too late for these questions. Mexican immigration had permanently changed both sides of the border. Once an elderly newspaper reader in the Kingsbury neighborhood called me to complain about the Hispanics who had so thoroughly changed the area. She wanted everything to go back to the way it was before. But that was a fantasy.

What was done was done. Business interests, their political allies, and human rights groups would not tolerate a forced mass migration out of the United States.

Isaias and Dennis would never brush the dust off their childhood bicycles and ride them again. The birth of Dustin could not be reversed, nor could the births in America of millions of other children of immigrants—all U.S. citizens.

For Isaias, his family, and the rest of America, the only way out was forward. That meant mining the untapped talent among children of immigrants at places like Kingsbury High and making sure that these children truly became part of America.

Cristina wanted to move forward too. She later told me she’d thought about returning to Santa Maria Asunción and living in the house where Maria Ines lived now. “But that’s like wanting to roll back your life ten years,” she said. “You can’t hide everything that you lived through. That’s why it’s better that we move forward and seek other places. Get to know people. Now it’s too late to go backwards.”

Nor did Isaias want to go back to Mexico. In his mind, it was a sort of dreamlike land where everything was perfect. He didn’t want to see the real country and spoil the illusion.

On the last day in Santa Maria Asunción, Dominic and I drove through the village and said goodbye to everyone who had helped us. Soon I flew back to the green city where Isaias still awaited his fate.