I HADN’T ALWAYS BELIEVED that Mario and Cristina really would go back to Mexico, especially after 2014, when they’d called off their plan. But Isaias understood that when his parents spoke of returning, they meant it.

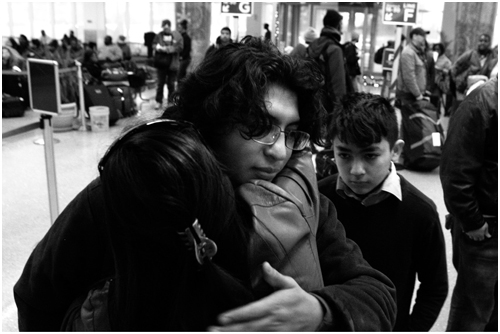

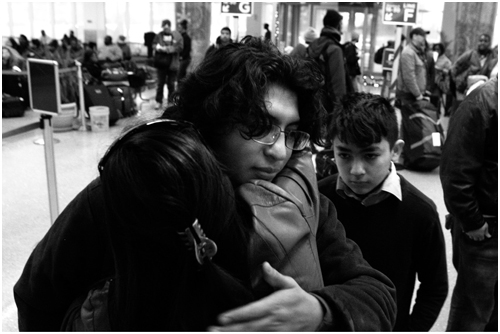

Late in 2015, a few days after Christmas, Mario and Cristina drove with their three sons to the city’s Greyhound bus terminal, a modern, spacious new building near the airport. They hugged Dennis, Isaias and Dustin goodbye, then walked through a portal to a waiting bus.

And then it was over in an instant, the sons on one side, the parents on the other, only a few feet away but somehow already irretrievably gone.

That day, Mario and Cristina rode the bus to Dallas, stayed overnight in a hotel, then awoke and boarded a plane to Mexico City, using a special discount fare that Isaias had found online: only $196 for the two of them.

Within hours, an image arrived on Isaias’ cell phone: an aerial view of Mexico City, the capital of the country that Mario and Cristina hadn’t seen since March 2003, a full 12 years, nine months earlier.

(Photo by Karen Pulfer Focht)

From the moment Mario and Cristina walked through that portal at the bus station, Dennis and Isaias bore the full weight of responsibility for caring for themselves and Dustin, who had now turned 12. They worked long hours on painting and remodeling projects because they would soon have to pay local property taxes on the house where they lived and the two other houses the family had bought in Memphis. And they’d need to send money to support their parents during the rough early months of preparing their old house in Mexico for sale.

A couple of weeks after Mario and Cristina left, Isaias said his younger brother appeared to be doing well. “I guess at one point I thought he was like, depressed or sad but no, it turns out he was tired that day.” When the older sons talked with their parents by phone or video conferencing, Dustin was there too. “And he’s okay with it,” Isaias said. “We’re actually having a lot of fun, the three of us.”

The sons ate dinner together. Isaias took Dustin to school every morning and told him to take out the garbage, and though the boy sometimes seemed grumpy, he did it. “He’s upbeat,” Isaias said. “He’s excited about things.”

Nearby, Rigo Navarro was living a similar life—his mother and father had returned to Mexico, too, and he and two of his brothers were likewise running a household on their own. “I see myself as the man, the wife and the maid of the house,” Rigo said. He said he always did the cooking, and that his mother was talking about staying in Mexico, though his father planned to come back and visit soon.

Mario and Cristina likewise spoke about trying to come back for an extended visit legally, with a visa, though an immigration attorney told me it might be very hard. The family members were considering sending Dustin to Mexico for a few weeks in the summer. Dennis and Isaias might one day be able to visit Mexico, too, if immigration authorities granted them special permission to leave and return.

The older brothers were making big changes in the house, turning their parents’ bedroom, as planned, into a music practice space. Their parents hadn’t liked pets, but Isaias and Dennis wanted them, and now they bought two young cats from the animal shelter. They named the gray one Cocoa and the tan one Sandy. Dustin called the cats “awesome.”

The band Los Psychosis stopped playing together. The Ramos brothers said Javi and his wife Stephanie wanted to pursue their musical careers with more professional ambition than the brothers did, and they parted ways on good terms. Some constants remained. Magaly and Isaias were still together. And for now, at least, the plaque of Jesus that Cristina had carried across the desert remained on the kitchen wall, just as she had left it.

The brothers were paying close attention to the 2016 presidential election campaign, in which Donald Trump and other candidates were making extreme anti-immigrant statements. Dennis and Isaias backed the Democratic socialist candidate Bernie Sanders, even donating to his campaign, though they couldn’t vote. For both the Ramos family and the country as a whole, the future was uncertain.

In the meantime, what are we to make of the story of Isaias and his decision not to continue in college?

Many people who read my December 2013 newspaper article on Isaias concluded that his story was about his immigration status and the problems it caused. Obviously, immigration problems did affect Isaias as well as his family. Yet other Kingsbury students with immigration problems, like Mariana Hernandez and Franklin Paz Arita, found ways to continue their college careers. After spending time with the Ramos family over a span of more than three years, I’m convinced that Isaias’ story isn’t only about his immigration status, but that it also reflects elements of family life and thinking that are common to many children of immigrants, even those who are citizens.

I don’t want to imply that immigration status doesn’t matter. It does, and immigration problems crushed many dreams at Kingsbury High. America allows these young people to live in the country indefinitely and educates them at great expense to taxpayers. Then after they finish high school, the country creates artificial barriers that make it more difficult for them to fulfill their potential. All of this is pointless and wasteful.

Still, passage of the Dream Act or something like it would not magically solve all the problems of America’s young Hispanics. Nationwide, the proportion of unauthorized immigrants among Hispanic kids in 2013 was only 3 percent. An additional 3 percent were legal immigrants. By far the biggest group was U.S. citizens born in this country: 94 percent.

Many students in Isaias’ graduating class had unauthorized immigration status, probably because the Mexican population in Tennessee was so new. But all the data suggest that the proportion of citizens among young Hispanics will continue to rise both in Memphis and across the country.1 The face of young Hispanics in America won’t be Isaias the unauthorized immigrant, but his little brother, Dustin the citizen.

In many cases, the lives of young Hispanics with citizenship will closely resemble the life of Isaias. Many will have immigrant parents who want their children to succeed in school but don’t know how to help and don’t speak English. Many teenagers will juggle academic demands along with work and family obligations. And many will wrestle with doubts about the value of education.

That’s why society should give children of immigrants extra supports like the ones that I’ve mentioned throughout the course of this book: expanded early childhood education, additional guidance counselors, scholarship funds and psychological interventions to improve students’ motivation to study. Indeed, all children from disadvantaged backgrounds need extra support.

Of course, these extra supports often cost money, and spending public money is a political question. The politics around immigration are so often so irrational that as of this writing, at least, an overhaul of immigration law appears far away. Many more years may pass before Congress sets new rules on how many immigrants to let into the country, or how to treat unauthorized immigrant adults. In November 2014, President Obama’s administration announced two more executive actions: an expansion of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and a program that would offer similar protection to unauthorized immigrant adults who were parents of U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents.2 Both programs faced legal challenges, and neither had been implemented as of this writing.

In the meantime, our society should view the millions of immigrants’ children as a powerful pool of human potential. We should handle matters related to immigrants’ children separately from the more controversial questions of immigration policy. Because so many decisions on education take place at the state and local levels, communities can and should make good choices for their kids independently, far from the heat and grandstanding of Washington politics.

And regardless of what governments do, adults who come into contact with children of immigrants can offer advice and encouragement. Throughout the course of my time at Kingsbury, I was struck by how much the students needed guidance, and I saw that interested adults could make a big difference.

If you’re an adult and you worry that you’re unqualified to help, or perhaps the wrong race or ethnicity, remember that in many cases, the student might have no one else to turn to. Kingsbury graduate Jose Perez said he didn’t really care who was offering help. “We’d rather get help from anybody than from nobody,” he said. “If our next-door neighbor can help us, we’ll be at our next-door neighbor’s house every day.”

Despite all the obstacles, many children of immigrants are succeeding in school and life. Students like Estevon, Magaly, Adam, Franklin and Mariana made it to college and stayed in. And even situations that look bleak can take surprising turns for the better. I recently walked into a bank near Kingsbury High and saw a nameplate for one of the tellers: Lorena Gomez, the teen mother whose life had been marked by enormous conflict and stress. She wasn’t in the bank that day, but I took her business card and later spoke with her by phone. Lorena said her daughter was well and that her relationship with her own mother had improved. She loved banking, hoped to advance in the field, and said her Spanish skills helped her work with Hispanic customers. “I feel useful for something,” she said. For Lorena, the future looked far brighter than it had a few short years before.

As the proportion of Hispanic youth in America slowly rises above one in four, we have reason to hope—and reason to remember what Rigo Navarro said one day in class:

Don’t give up on us.