It’s impossible to quantify the human costs that our overseas bases have inflicted on locals, military personnel, and their family members alike. However, we can try to add up the financial costs, though even this simple-seeming task quickly proves to be anything but.

One of the first people I went to talk to in my quest to tally the base nation’s bill was Andy Hoehn, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense in the George W. Bush administration. In his office at the government-funded RAND Corporation, Hoehn told me that many people who “advocate a forward presence” assume that the host countries are paying most of the costs.

But, Hoehn said, they’re not accounting for a lot. There’s the cost of buying airplane tickets for family members and shipping over all their belongings, for example. Plus you’ve got overseas housing and cost-of-living allowances, hotel rooms while waiting for permanent billeting, meals, per diems, and so on. When you have families, Hoehn added, the base also needs to build a school, a clinic, a church, and much more.

“It adds up,” I said.

“It adds up. And it’s routine,” Hoehn said. “And often these tours [abroad] are fairly brief. Three years and sometimes shorter.”

The problem is, Hoehn said, no one has really bothered to calculate the costs. Ultimately, he added, even “the services don’t know.”

In 2013, Hoehn’s RAND Corporation finally did a calculation. A nearly five-hundred-page study of overseas bases showed that “despite substantial host-nation financial and in-kind support, stationing forces and maintaining bases overseas produces higher direct financial costs than basing forces in the United States.”1 In Europe, for example, the Air Force’s estimated average annual cost just for running a base (before adding the costs of having any personnel there) is more than $200 million. That’s more than double the costs of an Air Force base in the United States.2

When it comes to personnel, the Air Force’s cost per person on an overseas base is almost $40,000 per year more, on average, than on a domestic base. The Navy’s annual cost per person in Europe is almost $30,000 more than domestically, while in Japan, the Army pays on average nearly $25,000 more per person every year than at home.3 Even in the least expensive case, that of the Marines in Japan, it costs $10,000 to $15,000 more per year for every marine stationed there compared to locations in the continental United States. For eleven thousand marines, that adds up to an extra $110 million to $165 million that taxpayers are spending every year to keep marine forces in Japan rather than in America.4 When one considers all the deployments globally, the numbers are staggering.

Another way to get a sense for the magnitude of the costs is this: because of the hundreds of bases overseas, the U.S. military is probably the world’s largest international moving company. Why? Because when stationed abroad for any period other than a temporary assignment, every member of the military generally has the right to ship his or her entire household and a personal vehicle to and from an overseas station.5 With tours generally lasting between one and three years, about one third of the military moves in any given year.

Among other things, this means the military is shipping tens of thousands of privately owned vehicles to and from bases overseas every year.6 Based on recent contracts, this is costing the government, and taxpayers, around $200 million every year.7

And that’s in addition to shipping every last piece of furniture, every book, every television, every kitchen pot and pan, every fork and spoon, every bicycle and children’s toy, and every other item in a uniformed service member’s household, up to a weight limit of 5,000 to 18,000 pounds (depending on rank and on whether one has family members).8 Which is in addition to the long-term storage of household goods for troops overseas, for which the military also pays. Which is in addition to miscellaneous expenses such as pet quarantine fees—which the military will also cover, up to $550 per move.9 Overall, the total annual moving costs alone easily stretch into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

THE OFFICIAL BILL

While overseas bases are clearly more expensive than domestic bases, the total bill for maintaining hundreds of bases and hundreds of thousands of troops abroad remains a mystery.10 In theory, we should know the total: by law, the Pentagon must tell Congress what it spends on all the military’s activities at bases, embassies, and other facilities abroad in an annual report called the “Overseas Cost Summary” (OCS).11 This means calculating all the costs of building, running, and maintaining every last base site, garrison, airfield, port, warehouse, ammunition dump, radar station, and drone base, plus the costs of paying for and maintaining every U.S. service member and family member abroad, including all their salaries, housing, schools, teachers, hospitals, moving costs, lawn mowing, utilities, and much, much more.

For the 2012 fiscal year, the Overseas Cost Summary put the total at $22.7 billion.12 That’s a considerable sum, roughly equal to the entire budget of the Department of Justice or the Department of Agriculture. It’s also about half the entire 2012 budget of the Department of State—significant portions of which actually go to arms sales, foreign military training, and other military (rather than diplomatic) purposes overseas.13

At the same time, however, the Pentagon’s official figure contrasts sharply with the only other recent estimate available. In 2009, the economist Anita Dancs estimated total spending on bases and troops abroad at $250 billion—a more than tenfold difference.14 Part of the discrepancy stems from Dancs’s including war spending in her total, whereas at Congress’s direction, the OCS doesn’t include the billions spent on the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere around the globe. But even without war spending, her figure comes to around $140 billion—still almost $120 billion more than the Pentagon suggests.

Faced with such a significant disagreement, I wanted to figure out the real costs of keeping so many bases and troops overseas. Trying to get a handle on the numbers, I talked to budget experts and current and former Pentagon officials, as well as budget officers at bases abroad. Many of the people I spoke to politely suggested this was a fool’s errand, given the number of bases involved, the complexity of distinguishing overseas from domestic spending, and the secrecy of Pentagon budgets. The “frequently fictional” nature of Pentagon accounting also poses a problem: the Department of Defense remains the only federal agency unable to pass a financial audit.15 Congress first ordered the Pentagon to make itself auditable in 1997; it has since missed numerous deadlines, and the goal is now 2017.16

Ever the fool, I plunged into the world of Pentagon budgets, where ledgers sometimes remain handwritten and $1 billion can be a rounding error.17 I reviewed thousands of pages of budget documents, government and independent reports, and hundreds of line items for everything from shopping malls to military intelligence to mail subsidies. Wanting to err on the conservative side, I decided to follow the basic methodology Congress mandated for the OCS18 while also including overseas expenses the Pentagon or Congress might have forgotten or ignored. It hardly seemed to make sense to exclude, for example, spending for troops in Kosovo, the price tag of bases in Afghanistan, or the costs of bases in overseas U.S. territories.19 Here’s an abbreviated version of my quest to establish the real costs.

MISSING COUNTRIES AND CONSTRUCTION

Although the Overseas Cost Summary initially seemed quite thorough, I quickly realized that countries widely known to host U.S. bases go completely unnamed in the report. In fact, around a dozen countries and foreign territories from the Pentagon’s own list of overseas bases appear to be missing from the summary. While they may be lumped into the “Other” category, for “countries with costs less than $5 million or unspecified overseas locations,” the absence of places such as Kosovo, Bosnia, and Colombia is surprising. The military has had large bases and hundreds of troops in the Balkans since the late 1990s; in a different Pentagon report, 2012 costs in Kosovo and Bosnia were listed as $313.8 million.20 According to the same report, I discovered that the OCS understates costs for bases in Honduras and Guantánamo Bay by about a third, or $86 million.

The OCS also reports costs of less than $5 million apiece for Colombia, Yemen, Thailand, and Uganda. Given current levels of military activity in each country, this seems highly unlikely. The costs of the military presence in Colombia alone could easily reach into the tens of millions a year, in the context of more than $9 billion in Plan Colombia funding since 2000. Unsure of the true spending in these countries, however, I decided to be conservative and not to replace the OCS figures with what would have been, at best, educated guesses. However, the real totals in those countries could add many tens of millions more.

Primed to look more carefully at the OCS, I found other oddities. In places like Australia and Qatar, the Pentagon reported having funds to pay troops’ salaries but no money for “operations and maintenance.” This would mean not having funds to turn the lights on, feed people, or do regular repairs. In other places, like Diego Garcia, there were no funds reported to pay personnel. Clearly, the report had either omitted the relevant figures or hadn’t gathered the data to include them. Using costs reported in other countries as a guide, I estimated another $35 million in spending for such locations. As a start, I found $435 million21 for missing countries and costs.

This is a relatively insignificant sum in the context of the Pentagon’s $22 billion estimate and certainly not much in the context of the entire Pentagon budget, but this was just the beginning.

TERRITORIES, POSSESSIONS, AND PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS

At Congress’s direction, the Overseas Cost Summary omits the costs of bases in the oft-forgotten parts of the United States lacking full democratic representation—places such as Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. This is strange because these areas are, of course, literally overseas, and because the Pentagon considers them “overseas” for accounting and other purposes.

Even more relevant for the purposes of calculating the base nation’s bill, as Dancs points out, is the fact that “the United States retains territories … primarily for the purposes of the military and projecting military power.” As we have seen, since World War II the government has largely hung on to this collection of islands because they’re home to critical bases like Andersen Air Force Base on Guam and the Saipan and Tinian bases in the Northern Marianas. Given this fact, one could reasonably regard all the federal spending in each territory as the cost of maintaining bases and troops there. Federal transfer payments to Puerto Rico alone were more than $17 billion in 2010, with the total for all the territories probably nearing $20 billion.22 To be conservative, however, I decided to focus strictly on explicit military spending. Spending on Guam is particularly high at a conservatively estimated $1.4 billion, including monies appropriated to the Pentagon and other agencies for the planned transfer of U.S. forces from Okinawa.23 I estimate that total spending for the remaining islands lacking full democratic representation reaches $1.2 billion.24 This brings us to around $2.6 billion more that’s not included in the OCS.

And beyond current U.S. territories such as Guam and Puerto Rico, one also needs to account for the Pacific Ocean island nations that were once U.S. “strategic trust territories”: the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. Eventually those areas gained their formal independence by signing compacts of free association with the United States. These compacts gave responsibilities for defense to the United States and allowed the U.S. government to retain military control over the islands; in exchange, the island nations get yearly aid packages, and their residents have greater rights to live in the United States than citizens of other countries. (They also have the right to join the U.S. military; per capita, the Federated States of Micronesia has a higher rate of enlistment and of death at war than any U.S. state.)25 Aside from the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site in the Marshall Islands’ Kwajalein Atoll, there is currently little military activity in the islands; the U.S. government is basically paying for the site and for base construction rights during wartime.

So what does that cost? Every year, the Department of the Interior’s Office of Insular Affairs makes payments as part of the compact of free association agreements. The transfers include rent to landowners in the Kwajalein Atoll and funds to provide health care and ongoing cleanup assistance to Bikinians and other Marshallese affected by nuclear testing. The Insular Affairs office is also responsible for such expenditures as the ongoing effort to control the invasive brown tree snakes that military cargo flights accidentally introduced to Guam. For 2012, such payments totaled $570.6 million, bringing the total cost here to $3.2 billion for territories and Pacific island nations.

SHIPS AND PERSONNEL OUTSIDE U.S. WATERS; PRE-POSITIONED SHIPS AND STOCKS

In a way, it’s strange, given the name of the Overseas Cost Summary, that it excludes (at Congress’s instruction) the costs of maintaining naval vessels overseas. After all, Navy and Marine Corps vessels are essentially floating and submersible bases used to maintain a powerful military presence across the planet’s waters. About 3.5 percent of Navy and Marine Corps personnel are afloat outside U.S. waters at a given time, so given total Navy and Marine Corps personnel and operations and maintenance costs of $108 billion, an estimate based just on that personnel percentage adds another $3.8 billion to the overseas budget. Of course, given the costs of far-flung operations and a total Navy and Marine Corps budget of $181 billion, this is an extremely conservative number; spending on fuel and other necessities away from home is likely to be considerably higher outside U.S. waters than domestically.26

Then there are the costs of Navy ships pre-positioned at anchor around the world in places like Diego Garcia and Saipan. These are like warehouse bases at sea, stocked with weaponry, war matériel, and other supplies. The Army also has pre-positioned stocks, in locations including Kuwait and Italy, that likewise aren’t included in the OCS. Together, these come to an estimated $600 million a year. The Pentagon also appears to omit some additional $860 million for overseas “sealift” and “airlift” and “other mobilization” expenses.27

Some might argue that the costs of maintaining a global navy, pre-positioned equipment, and sealift and airlift capacity shouldn’t be included in the cost of bases abroad, because those resources are what the military would “fall back to” if it closed all the overseas bases. This argument, of course, assumes that the United States must maintain military power around the globe, which is by no means self-evident. And whether or not one agrees with this proposition, the costs of pre-positioned equipment and vessels outside U.S. waters are clearly incurred overseas, rather than domestically, and should be counted here. All told, the bill grows by $5.3 billion for Navy vessels and personnel plus seaborne and airborne assets.

HEALTH CARE; MILITARY AND FAMILY HOUSING CONSTRUCTION; PX AND POSTAL SUBSIDIES

The Overseas Cost Summary includes the pay and extra allowances for military personnel abroad, but I confirmed with the Pentagon that, strangely, it doesn’t include health care and other benefits paid to troops.28 The Defense Health Program and other military personnel benefits, excluding those that are war-related, cost $31.2 billion and $51.8 billion, respectively, in 2012 worldwide.29 With 14 percent of all U.S. military personnel overseas, not counting troops directly involved in U.S. wars, I conservatively estimate that the same percentage of costs occurs overseas. This adds up to a little over $11.6 billion. Meanwhile, the Navy’s Expeditionary Health Services System costs some $66.2 million per year; since some of that spending is domestic, I add only half that amount to the overseas budget. This yields $11.7 billion for health care and benefits overseas.

While the OCS includes military and family housing construction costs submitted by each branch of the armed forces, it appears not to include military and family housing construction spending from Department of Defense–wide budgets. Such spending totals $3.6 billion, and since 15 percent of base sites are overseas, one can expect a roughly similar percentage of construction to take place there.30 This gives us an estimated $537.6 million in additional construction costs. There is also a much larger $4.6 billion in military construction spending at “unspecified locations” worldwide found in the Pentagon budget but missing from the OCS.31 Without knowing what proportion of this spending occurred at locations overseas, I again conservatively assume 15 percent (in fact, most of the spending may be abroad). This adds another $690 million in costs.

A much smaller, but significant, omission appears in the form of quality-of-life subsidies paid by the U.S. taxpayer. Take, for instance, the Post Exchange, or PX, which has long been an iconic feature of Army life on military bases at home and abroad. (Similar exchanges are called BXs by the Air Force, NEXs by the Navy, and MCXs by the Marine Corps.) These Walmart-like shopping malls are run by congressionally mandated government resale entities that enjoy retail rights on bases worldwide. In exchange for agreeing to return a portion of “reasonable earnings” to fund sports, libraries, and other recreational facilities and programs on bases, the Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES) and its Navy and Marine counterparts enjoy buildings and land free of charge, free utilities, and free transportation of goods to overseas locations. They also operate tax free, which partly explains why they have generated thriving black markets and “PX economies” for decades.32

While no one appears to have estimated the value of buildings, land, and utilities that taxpayers provide, AAFES and its counterparts do report some information about the subsidies they enjoy. In fiscal year 2012, the three Exchange companies received approximately $258 million in transportation subsidies, “contributed services,” and taxpayer reimbursements.33 Forgone federal, state, and local taxes would add tens of millions more to that figure. Meanwhile, postal subsidies to transport mail to and from overseas bases add up to at least $130.7 million.34 In total, you have $13.3 billion for health care, military and family housing construction, and shopping and postal subsidies.

“RENT” PAYMENTS AND NATO CONTRIBUTIONS

Another exclusion from the OCS is money paid to other countries whose land the Pentagon occupies. Although a few countries pay the United States to subsidize our bases, far more common, according to the base expert Kent Calder, “are the cases where the United States pays nations to host bases.”35 Though it is not officially framed as such, we can think of this effectively as a form of rent.

Given the secretive nature of basing agreements and the complex economic and political trade-offs involved in base negotiations, precise figures for these quasirental payments are impossible to find. However, it’s safe to conclude, as Calder says, that “the United States generally pays a lot of money for its foreign bases.”36 Using a representative sample, Calder calculates that when a country allows the United States to create a new base on its territory, military and economic aid to that country increase by an average of 218 percent and 164 percent, respectively, over the first two years of the base’s existence. After the creation of a base in Uzbekistan in 2001, U.S. military aid jumped from $2.9 million to $37.1 million the following year; economic aid leaped from $62.3 million to $167.3 million. (By contrast, when a country forces a U.S. base to close, military and economic aid decline during the first two years after closure by an average of 41 and 30 percent.)37

Calder’s research illustrates just how expensive gaining access to bases can be. Because his calculations are based on a small sample and because I prefer to err on the conservative side, I instead use an estimate from James Blaker, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense. Using Pentagon and other government data, Blaker calculates that around 18 percent of total foreign military and economic aid—subtracting Agency for International Development (USAID) funding—goes to buying base access.38 Given $31.5 billion in aid in 2012,39 this adds around $5.7 billion to total overseas costs.

On the other side of the accounting ledger, the OCS also omits cash payments the United States receives from countries such as Japan, Kuwait, and South Korea that help sustain U.S. bases on their territory. Budget documents from 2012 indicate the U.S. government received $889 million in “burden-sharing” payments and $225 million in “host nation support” for the relocation of bases—totaling approximately $1.1 billion paid for the U.S. overseas presence that year.40 Some countries also provide in-kind contributions of utilities and services rather than cash payments, but such contributions are not income received by the United States, so I have excluded them from these calculations.41

Aside from U.S. “rent” expenditures and “burden-sharing” receipts, the OCS also omits U.S. spending on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). During fiscal year 2012, the Pentagon budget included $247.6 million for U.S. contributions to the NATO Security Investment Program, which went toward “the acquisition and construction of military facilities and installations (including international military headquarters) and for related expenses for the collective defense of the North Atlantic Treaty Area.”42 The Pentagon also paid $3 million for the U.S. military mission to NATO in Belgium,43 while the Army, Navy, and Air Force spent a combined $533.7 million to support NATO and to provide “miscellaneous support to other nations.”44 And the United States contributed $889 million of its own burden-sharing payments to support NATO member countries and other allies.45

In sum, $5.7 billion in estimated quasirental payments and $1.7 billion in NATO contributions, weighed against $1.1 billion in receipts from other countries, yields $6.3 billion in NATO expenditures and net “rent.”

COMBATANT COMMANDS

The OCS also appears to overlook operations and maintenance funds and other spending that go directly to the Pentagon’s cross-service Unified Combatant Commands.46 Six of those commands—Africa, Central, European, Northern, Pacific, and Southern—divide the globe among them, and all of them operate in whole or in part overseas. So do the Special Operations and Transportation Commands.

The Northern Command mainly focuses on the continental United States, but it also patrols parts of Mexico, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, Canada, and the Arctic. Conservatively estimating that 5 percent of the Northern Command’s budget47 and half of funding for the other seven commands go to operations abroad adds an estimated $2.8 billion in funding for the combatant commands overseas operations.48

COUNTERNARCOTICS, HUMANITARIAN, AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAMS; OVERSEAS RESEARCH

Although the OCS must report the costs of all military operations overseas, I confirmed with the Pentagon that it omits around $550 million for counternarcotics operations.49 It also excludes the money spent on humanitarian and civic aid. Some of the humanitarian aid can be considered truly nonmilitary, but as a budget document explains, humanitarian operations crucially help “maintain a robust overseas presence” and obtain “access to regions important to U.S. interests.”50 Again erring on the conservative side, I include only half of the humanitarian spending in my calculations, which adds $54 million. The Pentagon also spent $24 million on environmental projects abroad to monitor and reduce its on-base pollution, to dispose of hazardous and other waste, and for “initiatives … in support of global basing/operations.”51

The military also maintains a large collection of research laboratories overseas. Given the CIA’s use of a fake childhood vaccination campaign to help locate and kill Osama bin Laden, it is doubtful that all these research activities are purely scientific. At the very least, they constitute another way the Pentagon builds military-to-military ties, gains influence, and broadens the U.S. military presence abroad.

Funding for these labs is hard to find within the overall Pentagon budget, but the Cooperative Biological Engagement program offers one visible example. This $259 million program builds and operates labs and other activities to counter the threat of biological weapons in countries such as Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, and Burundi.52 While some of this program’s funding seems to be spent domestically, any overestimate here is likely offset by harder-to-locate funding for other overseas labs. The bill now grows by $887 million for counternarcotics, humanitarian, and environmental programs, and overseas research.

CLASSIFIED PROGRAMS, MILITARY INTELLIGENCE, AND CIA PARAMILITARY ACTIVITIES

Not surprisingly, the Pentagon tally omits the cost of secret bases and classified programs overseas. In 2012, the Pentagon’s classified budget was estimated at $51 billion.53 Applying the OCS methodology, I focused on the operations and maintenance spending portion of that total, which was estimated at $15.8 billion.54 As elsewhere, I conservatively estimate the overseas portion of that spending at 15 percent (the percentage of base sites overseas), adding $2.4 billion to the cost of bases abroad. Since classified spending is more likely to take place overseas than domestically, this is almost surely an underestimate.

Then there’s the $21.5 billion Military Intelligence Program.55 Given that U.S. law generally bars the military from engaging in domestic spying (NSA revelations notwithstanding), I estimate that half this spending—$10.8 billion—took place overseas.

Since the onset of the war on terror, CIA paramilitary activities have grown dramatically.56 These activities have included the creation of secret bases in places such as Pakistan, Somalia, Libya, and elsewhere in the Middle East, as well as the CIA’s drone assassination program.57 In short, the intelligence agency has become a major war fighting force. With thousands killed by CIA operations, it only makes sense to consider its expenditures as military costs. In the fiscal year 2013 black budget, released by the Washington Post, the CIA received $2.6 billion for “covert action,” which would include the drone program and other paramilitary operations abroad, and about $2.5 billion for its war operations.58 Because adding these two figures may double-count some spending, I use only half of the “covert action” costs. In total, this yields $17 billion for classified programs, military intelligence, and CIA paramilitary activities.

THE TOTAL BILL

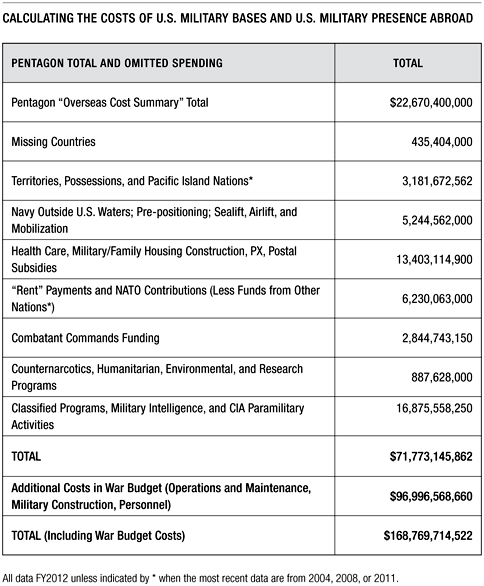

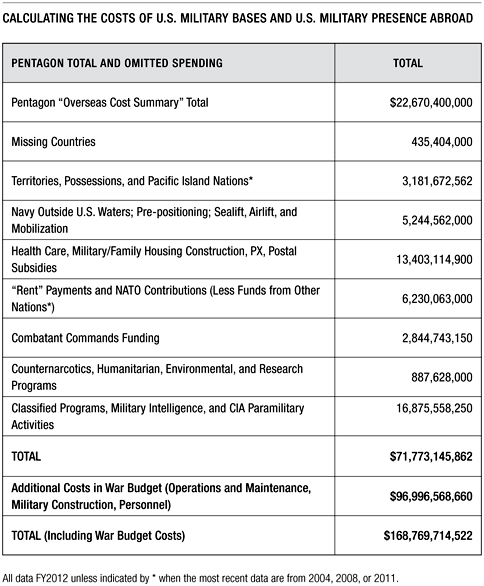

Having started with the OCS figure of $22.6 billion, my total now reaches $71.8 billion, which is more than three times the Pentagon’s calculation. Given my very conservative estimates, the true total could easily be much higher. For example, the Pentagon never replied to my inquiries asking whether all the costs of Department of Defense schools overseas are included in the OCS. If they are not, school costs could add more than $1.3 billion more to my total.59

Far more significantly, my $71.8 billion calculation does not include the costs of maintaining bases and troops in war zones such as Afghanistan and Iraq. Congress instructs the OCS to exclude all of the costs of maintaining bases and personnel overseas if those costs are funded by war appropriations, which appear in a separate annual Overseas Contingency Operations budget. On the other hand, one could argue that the entire war budget should be counted: after all, war spending crucially helps maintain the physical security and political legitimacy of U.S. bases in Afghanistan, Iraq, and beyond. Calculating the overseas base expenses without including the immense costs of the “contingency operations” revolving around those bases is a bit like setting up a family budget without accounting for the cost of a luxury vacation beachfront rental, or discussing the finances of the New York Yankees while excluding the cost of the team’s big free-agent signings.

Still, in determining how much war spending has supported bases and military personnel overseas, I stuck with the OCS methodology. I excluded funding for procurement, research, and similar activities, and focused on the costs of military personnel, operations and maintenance, military construction, and health care. Those costs represent approximately 75 percent of the total war budget.60 Using data for fiscal year 2012 to match the other calculations in this chapter, I applied that percentage to Congress’s $107.5 billion in war appropriations for Afghanistan and the final months of the U.S. occupation of Iraq. This yields an estimated $80.6 billion in additional war spending.61

The official $107.5 billion war appropriations figure for fiscal year 2012 is itself arguably a significant underestimate. There are many other costs of war that Congress does not include in the Overseas Contingency Operations budget, including medical and disability care for veterans, interest payments on past appropriations, and perhaps even additions to the Department of Homeland Security budget necessitated by the increased threat of terrorist attacks launched in response to U.S. military actions. Using numbers provided by Brown University’s Costs of War project, such considerations might have brought the actual war spending total to almost $130 billion in 2012 alone.62 Future costs for veterans’ medical and disability care would bring the total even higher.

To err again on the conservative side, I have not included these unacknowledged expenses in my calculation. However, my $80.6 billion figure is also incomplete in another way: war funding only pays for “incremental” costs, above those found in the normal Pentagon budget. So I also had to account for war zone troops’ basic salaries and other personnel costs, which I calculated at around $14.3 billion (employing a widely used $125,000 per troop per year cost estimate). I also found another $74.9 million in “Wounded Warrior Care” health costs tucked away in the Pentagon budget.63 Finally, I calculated almost $2 billion in “rental” costs—in the form of military and economic aid—for bases in Afghanistan and Iraq, using the previously detailed methodology from James Blaker.64

With those additions, my estimate of war zone costs for 2012—including appropriations for military construction and maintenance, troop salaries, and so on—was $97 billion. My estimate for the total costs to maintain U.S. bases and troops around the globe—both within war zones and outside them—thus reached some $170 billion for fiscal year 2012.

Since 2012, Pentagon spending has fallen somewhat, due to the end of U.S. operations in Iraq, the gradual withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, and Congress’s sequestration process. Accounting for those declines and adjusting my estimate for the latest complete fiscal year, 2014, yields an estimate of $64.4 billion for the costs of bases and troops abroad outside war zones. Adding the costs of bases and troops in Afghanistan and other war zones would bring the total to around $136 billion for 2014.

Even if one excludes spending on the war in Afghanistan from the final bill for the base nation, there seems little reason to ignore billions of dollars in war funding that has actually gone to funding bases, troops, and regular operations in countries other than Afghanistan, including places in the Persian Gulf, Central Asia, Africa, Europe, and elsewhere. In recent years, the Pentagon has increasingly used war budgets to evade spending caps on its regular “base” budget imposed by sequestration’s Budget Control Act. In fiscal year 2014, for example, at least $19.9 billion funded “in-theater support” outside Afghanistan.65 Adding that figure to my $64.4 billion estimate for 2014 shows that, at a minimum, the full cost of maintaining bases and troops overseas that year was some $85 billion.

Plus, there’s more spending for which I couldn’t account. In addition to money surely hidden in the nooks and crannies of the budget, there are Pentagon expenses that clearly support overseas bases but are too difficult to estimate reliably. Examples include the cost of offices and personnel who are supporting bases and troops overseas but who are located at the Pentagon itself, in embassies, and in other government agencies. Overseas bases also make use of (and thus incur expenses for) training facilities, depots, hospitals, and even cemeteries in the United States. Other costs could include the costs of Coast Guard operations overseas; foreign currency exchange fees; attorneys’ fees and damages won in lawsuits against military personnel abroad; short-term “temporary duty assignments” overseas; U.S.-based troops participating in overseas exercises; some of NASA’s military functions; the Pentagon’s space-based weapons; a percentage of recruiting costs required to staff bases abroad; interest paid on the debt attributable to the past costs of overseas bases; and Veterans Administration costs and other retirement spending for military personnel who worked abroad.

Even with recent reductions in military spending, the annual cost to taxpayers to maintain bases and troops overseas in coming years could easily reach $100 billion or more given the conservative nature of my calculations and the Pentagon’s use of war budgets to fund nonwar activities. At these levels, if Pentagon spending abroad were its own government agency, it would have a larger discretionary budget than every other federal agency except the Department of Defense itself. Including the costs of maintaining bases and troops in war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq could bring the base nation’s total bill to $160–$200 billion—which is two to three times the size of the discretionary budget of the Department of Education, for example.66

SPILLOVER COSTS

We also have to remember that these estimates represent just direct costs to the U.S. government’s budget. The total costs to the U.S. economy of keeping bases and military forces abroad are even higher. Consider where the (taxpayer-funded) salaries of troops go when they eat or drink at a local restaurant or bar, buy clothing, or rent a home in Germany, Italy, or Japan. These are what economists call “spillover” or “multiplier effects.” When I visited Okinawa in 2010, Marine Corps representatives bragged how their presence contributes $1.9 billion to the local economy through base contracts, jobs, local purchases, and other spending. While there are reasons to be skeptical about the accuracy of this particular figure (for example, a considerable portion of marines’ economic impact comes from Japanese government rental payments and subsidies), the scale of the impact makes it easy to understand why some members of Congress want to bring overseas bases home, where more of that spending would go into the economies of their districts and states instead.67

The true costs of the base world are even higher when one considers the trade-offs, or opportunity costs, involved. Military spending creates fewer jobs per billion dollars expended than the same billion dollars invested in education, health care, or energy efficiency—less than half as many jobs as investing in schools, for example.68 Even worse, while military spending provides direct benefits to military contractors such as Lockheed Martin and KBR, these investments don’t boost long-run economic productivity the way infrastructure investments do.69

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower famously said,

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this:

A modern brick school in more than 30 cities.

It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population.

It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals.

It is some 50 miles of concrete highway.

We pay for a single fighter with a half million bushels of wheat.

We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people.70

So, too, every base that is built overseas signifies a theft from American society. Reallocating the $75 billion to $100 billion in total annual expenditures on overseas bases would allow the country to roughly double federal education spending, for example. Today, Eisenhower might say the cost of one modern base is this:

A college scholarship for a year for 63,000 students.

It is 295,000 households with renewable solar energy for one year.

It is 260,000 low-income children getting health care for one year.

It is 63,000 children getting a year of Head Start.

It is 64,000 veterans receiving health care for a year.

It is 7,200 police officers for one year.71

Meanwhile, the costs to host countries are also steep. They include financial expenses, like the money spent cleaning environmental damage, soundproofing homes, and paying damages for crimes committed by U.S. troops.72 They also include, as we have seen, nonfinancial forms of spillover, ranging from environmental damage to the support offered for repressive governments to sexual assault and rape. These, in turn, impose on the United States and its citizens what the economist Dancs calls the “costs of rising hostility,” reckoned in the damage done to the country’s international reputation and its standing in the world.

From the billions of dollars wasted to the human costs that can’t be quantified, we all pay. The question that remains, then, is who’s benefiting from all this spending?

KBR employees preparing food for troops, Camp Fallujah, Iraq, November 2008.