In late 2010, to help prepare a group of students learning about U.S. bases for a study trip to Okinawa, I arranged a meeting with Kevin Maher at the State Department’s Foggy Bottom headquarters. Maher had been a diplomat for thirty years. For eighteen of those, he had held various diplomatic posts in Japan before becoming director of the State Department’s Japan desk.1 With his crisp shirt and tie, polished leather shoes, perfectly parted red hair, and small, carefully trimmed red mustache, he was the very picture of a seasoned official in the national security bureaucracy.

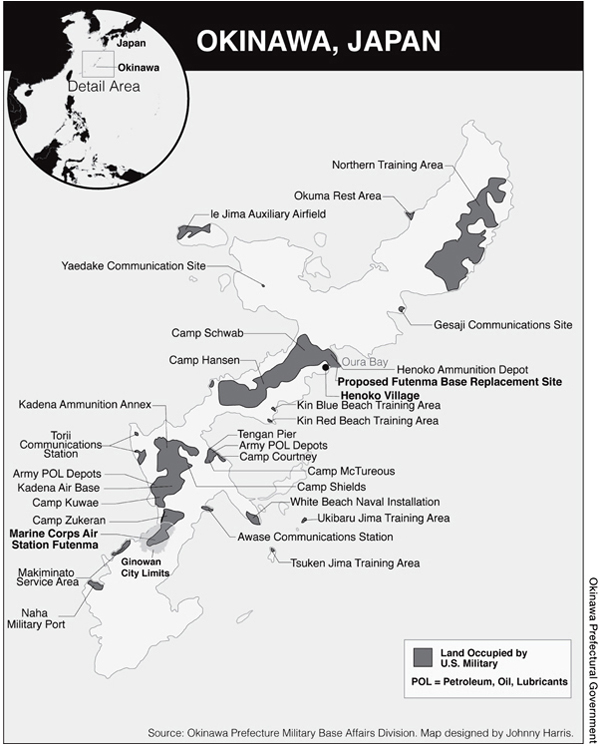

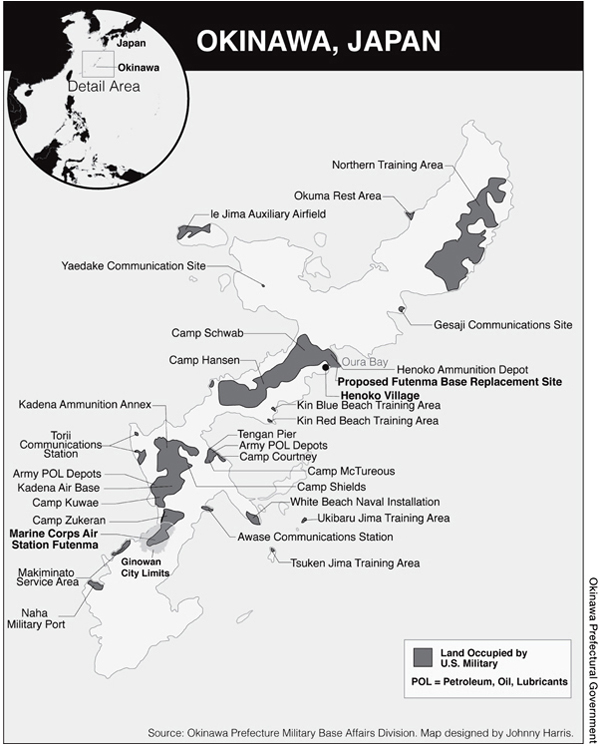

Although the Okinawa prefecture makes up just 0.6 percent of Japan’s land area, it is home to around 75 percent of all the military installations in Japan set aside for exclusive U.S.use—more than thirty bases altogether. American bases take up almost 20 percent of the main Okinawa island, in addition to expansive sea and airspace the military uses for training. And ever since the 1995 gang-rape of a twelve-year-old Okinawan girl, it has been among the most controversial and hotly protested base locations worldwide.2

“Look at the map,” Maher told our group, explaining why so much of Okinawa was taken up by U.S. forces. Okinawa is closer to North Korea and China than to Tokyo, he pointed out, so in a way, Okinawans are “victims of geography,” with a military presence there critical for guaranteeing regional security. Plus, Maher added, we get “friendly and great facilities,” in a place that’s a great location for Americans.

Then Maher expounded a bit on the island’s history. Okinawa was colonized by Japan in 1879, he said, and a lot of the American bases there stem from the U.S. occupation of Japan after World War II. So Okinawa sits in an “interesting triangular relationship” with Japan and the United States. “This is not a politically correct way to say it,” Maher added, “but, as a man in Okinawa told me, it’s the Puerto Rico of Japan.” Like Puerto Ricans, he said, Okinawans have “darker skin,” are “shorter,” and have an “accent.”

This was not the briefing we had expected from someone with a job description involving diplomacy.

Okinawans, Maher continued, are “masters in extorting Tokyo for money.” Most of the bases sit on private land leased by the Japanese government for the United States. When the leases come up for renewal, he said, you see a lot of Okinawan politicians and others calling for the removal of bases, but he didn’t think they really wanted the bases to leave. “That’s how you jack up the price on the rent.”

Plus, Maher explained, Tokyo pays Okinawa compensation in the form of construction contracts. These mostly go to politicians’ relatives, he said. You always hear that “Japanese culture” is so “group oriented” and focused on “consensus building”—but “that’s such bullshit,” he told us. “The ‘group’ is me and my buddies here.” Maher said that payoffs were common in Japanese culture. “Okinawans are masters at this,” at getting Tokyo’s money and using “guilt” about Okinawans’ suffering during World War II to do it.

Despite the construction contracts, Maher said, Okinawa is still the poorest prefecture in Japan. He said it was “partially because it was occupied until 1972” by the United States and wasn’t integrated into the Japanese economy. But “you’ve got this island mentality,” he added. That mentality traditionally involved planting sugarcane and goya (a bright green cucumber-shaped bitter melon iconic in Okinawa), and then just waiting around until cutting it down. And nowadays, Maher said, “They are too lazy [even] to grow it.”3 Before finishing the briefing, Maher attributed Okinawans’ high rates of divorce, drunk driving, domestic violence, and childbearing to their taste for Okinawan rice liquor.

After Maher’s briefing, our astonished group convened in a nearby café. Almost everyone was shocked by his characterizations. A student with Okinawan grandparents was so stunned he couldn’t speak.

Several days later, at the suggestion of a Japanese graduate student in our group, a few students decided that when our study trip was done, they would share what we had heard with a Japanese journalist. I said I would back them up if anyone challenged their account; the meeting hadn’t been recorded, but I had taken detailed notes. None of us had any idea of the uproar that would follow.

In March 2011, two months after our student group returned to Washington, the Japanese news agency Kyodo News published an article about Kevin Maher’s pretrip briefing. The article used quotes from Maher’s talk that the students had provided to the journalist Eiichiro Ishiyama. Okinawans and others were outraged, particularly with Maher’s description of the Okinawan people as “extortionists” and “lazy.” The article became front-page news in Japan, and Maher’s comments were reprinted worldwide. Within three days, Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell was issuing official apologies in Tokyo, and the State Department was removing Maher from his post.4

The “Maher Affair” was supplanted on the front pages in Japan only by the earthquake and tsunami that triggered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. During the disaster, Maher reportedly played an important role in the U.S. government’s humanitarian response. The next month he retired from the State Department. He commented on the uproar for the first time in a video interview with the Wall Street Journal. In the interview, Maher denied ever making the statements attributed to him, calling them “a kind of fabrication.” He said the comments had been invented by the students.5

Outraged, I wrote a letter to the editor confirming the accuracy of the students’ report. I also noted that, contrary to the Wall Street Journal’s description, neither Maher nor any State Department employee had told us at any time that the meeting was “off the record.”6

Many expressed little surprise that Maher had made the derogatory comments. Former Okinawa governor Masahide Ota wrote that Maher had “a track record of making such verbal gaffes—statements that undoubtedly represent his true feelings.”7 When Maher was consul general in Okinawa, he was so disliked that he earned the nickname “High Commissioner,” a reference to the U.S. high commissioners who ruled Okinawa until 1972. A longtime U.S. reporter and analyst of U.S.-Japan relations, Peter Ennis, pointed out that no State Department or Japanese government officials rushed to Maher’s defense. There were “no comments to the effect: ‘Kevin, I can’t believe they distorted your comments so much,’ or ‘Don’t worry, everyone knows you didn’t say those things.’”8 Instead, Ennis quoted a senior Japanese reporter in Washington: “We had heard Kevin say things like this in the past.”9

Maher’s comments inflicted widespread hurt in Okinawa and Japan. His characterization of Okinawans as “lazy” and possessing an “island mentality,” and his disparaging comparison of Okinawans to Puerto Ricans—successfully offending not one but two groups of people—are so offensive in deploying racial stereotypes that they speak for themselves. (The comments about “lazy” Okinawans are especially remarkable given that thousands of Okinawan employees help keep U.S. bases running.) On the other hand, linking the Puerto Ricans and Okinawans was inadvertently apt. Both cases sadly illustrate how an occupation by U.S. bases and troops works as part of a larger colonial relationship, impoverishing the occupied land and shaping many of the very real social problems found on both islands.

Despite the hurt Maher caused, many were pleased his views were aired. For many, far from looking like an aberration, the incident exposed some of the attitudes long underlying U.S. basing policy in Okinawa. An Okinawa Times newspaper editorial said Maher’s comments showed that U.S. officials “seem, deep in their hearts, to despise Okinawa and make light of the base problem.”10 Okinawa’s other major daily, the Ryukyu Shimpo, wrote that Maher had provided, “unintentionally, a revelation of real U.S. thinking.”11

THE BATTLE OF OKINAWA

Okinawa feels more removed from Tokyo than the two-and-a-half-hour flight would suggest. For centuries, the archipelago existed as the independent Ryukyu Kingdom, best known for forsaking weapons and inventing karate. After Japan colonized the islands, it used them as a military outpost for further imperial incursions into Asia. The government banned the use of the Okinawan language in public and enforced other discriminatory policies against ethnic Okinawans.12 Tokyo restaurants once displayed signs saying NO OKINAWANS ALLOWED.

Okinawa Island is about the size of New York City, and most of the population lives in the island’s southernmost third, which is almost entirely one unbroken, paved urban area. Satellite images show the stark divide: lush green on top, gray below. Outside the shiny capital, many of the cities and towns look like run-down strip-mall American suburbia—roads clogged with cars and lined with car dealerships, fast food joints, small casino parlors, and 100 yen stores (the Japanese version of dollar stores). Almost every one of the densely packed buildings dates from after World War II, because almost every town and village on the island was bombed, burned, or razed during the 1945 Battle of Okinawa.

Little remembered in the United States, the three-month battle was the Pacific war’s largest and deadliest. American strategists wanted to capture Okinawa for use as the main launching point for an invasion of Japan, while the Japanese military hoped to bog down the Americans on Okinawa for as long as possible to build up the main islands’ defenses and negotiate an advantageous end to the war. U.S and allied naval vessels bombarded Okinawa with around forty thousand shells in what became known as the “typhoon of steel.”13 Between 100,000 and 140,000 Okinawans—one quarter to one third of Okinawa’s population—likely died during the fighting. Warned by Japanese leaders about savage American soldiers, some committed suicide by throwing themselves off the jagged cliffs along the coast. Others used hand grenades provided by Japanese troops. Some were forced to kill family members. A total of 1,202 cases of forced mass suicide have been documented.14 Including the 12,520 U.S. troops and the more than 90,000 Japanese troops and Okinawan conscripts killed in action, as many people may have died during the Battle of Okinawa as in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.15

At the time of the Battle of Okinawa, Masahide Ota, the prefecture’s future governor, was a teenager. The Japanese army conscripted him along with the rest of his high school. Only 37 of 125 classmates survived; Ota himself nearly died but was captured and sent to a prisoner of war camp. In a meeting with our student group, Ota said that initially, “Okinawan people’s attitudes were so thankful to American soldiers.” Whereas Japanese soldiers abandoned and killed hundreds of Okinawans, Americans “saved lives” during the battle. But in the early 1950s, Ota said, the Americans “confiscated Okinawan people’s lands by force … Ever since, people’s attitudes have changed.”

Many Okinawans had lost their lands during the battle itself, when they were forced to flee for safety. Thousands of Okinawans like Ota spent months in displaced persons’ camps and were barred from returning home. In many cases, there was little to go home to. Most everything had been flattened by the Allied bombardment. Ninety percent of the capital, Naha, was destroyed.16 U.S. forces immediately began building bases atop villages and fields for the planned invasion of Japan. Within a year, the United States had seized forty thousand acres—equal to 20 percent of the island’s arable land.17

When a Time magazine reporter visited in 1949, he found that “the battle of Okinawa completely wrecked the island’s simple farming and fishing economy: in a matter of minutes, U.S. bulldozers smashed the terraced fields which Okinawans had painstakingly laid out for more than a century.” Four years later, Okinawa had become a neglected place. “More than 15,000 U.S. troops, whose morale and discipline have probably been worse than that of any U.S. force in the world, have policed 600,000 natives who live in hopeless poverty.”18

During the postwar occupation of Japan, U.S. negotiators insisted on retaining full control of Okinawa after nominally returning it to Japan.19 Thus, when the occupation of Japan ended in 1952, the United States continued to rule Okinawa and smaller islands like Iwo Jima. American officials described Japan as maintaining “residual sovereignty” over these islands, but the U.S. government retained the right to establish military facilities on them, and effectively to govern them as it wished.20 This arrangement was politically palatable to Japanese leaders because concentrating U.S. bases and troops in a colonized part of Japan meant reducing the U.S. military’s impact elsewhere.21

In Okinawa, neither the new (U.S.-imposed) constitution of Japan nor the constitution of the United States applied. The occupation government required Okinawans to obtain a U.S-issued travel pass to visit Japan and controlled the movement of Japanese visitors to Okinawa. With U.S. troops back at war in Korea, the military began a major base buildup. By the mid-1950s, the military had displaced nearly half the population and appropriated almost half of Okinawa’s farmland by negotiation or force.22

More than 80 percent of Okinawans were farmers, Ota explained, so without their land, “they had no way to make a living.” The appropriation of land also “disturbed the development of towns and cities” because “the most important areas” were occupied by bases. (Today, Okinawan families must get special permission to visit the tombs of their ancestors that lie within bases’ fenced-off boundaries.) It’s unfair that Okinawa was occupied when Japan regained its sovereignty, Ota said, “because we didn’t start the war.”

“INCIDENTS AND ACCIDENTS”

Starting with the first months after the war, there were scattered protests in Okinawa against the occupation, the land seizures, and the often heavy-handed U.S. occupation officials. Protests intensified in the 1950s and 1960s, partly due to opposition to the Vietnam War, during which Okinawan bases played an important role. The outcry was also fueled by a series of deadly jet crashes and vehicle accidents, as well as the dozens of rapes, murders, and other crimes involving GIs.23

Okinawans have long taken note of what they call “incidents and accidents” involving U.S. troops. In 1951, for instance, an Air Force fighter dropped a fuel tank on an Okinawan house, burning it to the ground and killing six residents. Eight years later, an Air Force jet crashed into an elementary school, killing seventeen students and teachers and injuring more than one hundred. Between 1959 and 1964, at least four Okinawans were shot and killed as the result of what military officials said were hunting accidents or stray bullets from training. Between 1962 and 1968, there were at least four more crashes and accidents involving military aircraft, leaving at least eight dead and twelve injured. At least fourteen people died after being hit by U.S. military vehicles, including a four-year-old killed by a crane.24

Not all the deaths were accidental. In 1955, a court convicted a U.S. sergeant of abducting, raping, and killing a six-year-old girl. During the Vietnam War, reports suggest that U.S. military personnel deployed to Okinawa or on leave there killed seventeen women. Eleven of them had been working as bar hostesses or sauna attendants.25

In 1962, the Okinawan legislature passed a unanimous resolution condemning the United States for engaging in colonial rule, and by 1968, 85 percent of Okinawan and Japanese survey respondents favored the immediate return of Okinawa.26 Eventually, Prime Minister Eisaku Sato and President Richard Nixon negotiated the return of Okinawa to Japanese rule by 1972. However, the actual base land to be returned was minimal. The proportion of U.S. bases in Okinawa as opposed to the rest of Japan would actually increase. The agreement failed to mollify many Okinawans.

Only after the 1995 schoolgirl rape and the uproar it provoked did Kevin Maher and other U.S. and Japanese officials finally negotiate to reduce Okinawa’s base burden. In a 1996 agreement, U.S. officials pledged to return 12,361 acres of Okinawan land. It also promised to implement noise reduction mechanisms and changes to training procedures to reduce friction with neighboring communities.

Most important, the military also agreed to close the controversial Marine Corps Air Station Futenma. Built atop five villages destroyed during World War II, Futenma is now surrounded by Ginowan, a densely populated city of almost a hundred thousand. The airfield is only a few hundred yards from numerous schools, child care facilities, apartment buildings, and hospitals. In some cases, houses and playgrounds are just a matter of feet from the base’s fences. Low-flying helicopters and planes are a nearly constant visual and aural presence. At Okinawa International University, just a few hundred yards from the airfield, our tour group witnessed students and faculty forced to close the windows in an extremely hot and humid, un-air-conditioned building because they couldn’t hear one another talking above the helicopter noise. Even more seriously, there are no safety “clear zones” beyond Futenma’s runways, as the law requires at U.S. military and civilian airfields. Airports worldwide are often situated in urban areas, but Futenma is so surrounded by Ginowan that it looks as if someone dug a 1,188-acre hole in the middle of the city.

“In the United States, a base with encroachment this severe,” writes the retired Air Force officer Mark Gillem, “is a base that would find itself on the closure list.”27 Okinawans frequently invoke a phrase attributed to former secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld calling Futenma “the World’s Most Dangerous Base.”

But when the U.S. and Japanese governments signed their 1996 agreement, there was a catch: the military wouldn’t close Futenma until the Japanese government built the Marines a new base. And although most Okinawans expected the replacement would be outside their prefecture, the two governments selected a site on Okinawa’s east coast, near an existing base called Camp Schwab.

Initially, Japanese officials proposed having the new base float on water. This idea came under intense criticism. Military officials were concerned about its technical feasibility. The General Accounting Office pointed out that the estimated annual operating costs were seventy times those at Futenma. Many were worried about the safety of plans to store ammunition under the runway. Environmentalists were concerned that the new base would seriously damage the maritime environment. Because of possible threats to the endangered dugong, a relative of the manatee, they filed a suit against the Pentagon and won a temporary block to construction. Voters in the proposed host city, Nago, have repeatedly opposed the new base.28

In 2005, the two governments finally agreed to change the plan. They announced that the base would be built at Camp Schwab, on a runway extending into Nago’s Oura Bay. But environmentalists and others again expressed concerns about the impact of the new proposal on coral reefs and on marine life such as the dugong. Some in Nago’s Henoko village risked their lives by taking their protest into the water to block construction. One protester told our group, “I will keep fighting even after I’m dead.” By 2014, the Henoko village activists and their supporters marked a decade of sit-ins protesting the new base.29

THE STATUS OF FORCES

Deadly accidents, violent crime, and local anger have been a constant almost everywhere there are bases. Across the globe, it’s clear that the impunity and power felt by troops can lead to theft, assault, rape, and murder. While only a minority of troops is involved, the effects of these attacks are profound not only for the victims, but for the broader local populations, who rarely regard crimes committed by the armed foreigners occupying their land as isolated events.

Some military leaders “will unhelpfully explain that soldiers commit fewer crimes per capita than residents of the host nation,” notes Gillem. “Other officers recognize that numbers do not matter; any crime committed by U.S. soldiers is automatically an international event.” As a former public affairs officer for U.S. Forces Japan explains, the crimes are seen “as an additive thing. They don’t look at it as a rate—crimes per thousand or crimes per 100,000. It’s just one more crime on top of a long history of earlier misconduct.”30

In Germany, crimes committed by GIs during the Vietnam era helped sour many on the golden years of American occupation. As the war dragged on, the Army stationed some of its least well-trained troops in Germany. Base conditions deteriorated, and dissension and disorder grew accordingly. What’s more, the value of the dollar against the mark had declined dramatically, and GIs suddenly felt and looked poor in the eyes of many Germans. Drug use was rife. Reports of mugging, robbery, assault, rape, and arson by GIs became common. In 1971, there was outright “insurrection,” with soldiers in Wiesbaden refusing to participate in an exercise. VIETNAM HAS POISONED THE U.S. ARMY IN GERMANY, read one West German newspaper headline. Another declared, AMERICAN TERROR AS NEVER BEFORE. The paper explained, “They are supposed to protect us. But they rob, murder, and rape. American soldiers in Germany arouse naked fears.” With racial tensions in the military also exploding into view, in 1972 a newspaper described a clash in Stuttgart between African American GIs and German police as “the bloodiest pitched battle on the streets … since World War II.”31

The cumulative result of these various problems—economic strain, crime, drugs, and racial conflict—was, as the historian Daniel Nelson says, that “a process of long-term atrophy in bedrock support for NATO and the American presence was set in motion in Germany.” It would be a support that “could never be reproduced.”32

In the Philippines, GI crimes similarly helped energize the movement that forced the U.S. military to leave the country in the early 1990s. More recently, a marine, who is among the hundreds of U.S. troops to return to the Philippines since 2002, was charged with murdering a transgender Filipina, who was found with a broken neck on a hotel room toilet.33 In South Korea, support for U.S. troops—long credited with protecting the South from communist invasion—was profoundly shaken when an armored vehicle killed two teenaged girls during a training exercise in 2002. The largest-ever protests against the U.S. presence followed.

The situation is only made worse by status of forces agreements (SOFAs) that often allow U.S. troops to escape prosecution by host nations for the crimes they commit. Little known in the United States, SOFAs govern the presence of U.S. troops in most countries abroad, covering everything from taxation to driving permits to what happens if a GI breaks the host country’s laws. Each SOFA is different. Base expert Joseph Gerson once told me the length of a SOFA usually bears an inverse relationship to the power differential between the United States and the host country: the greater the power of the United States relative to the host, the shorter the SOFA, placing fewer restrictions on the military and its personnel.

When a Marine jet flying too low and too fast in Italy in 1998 severed a gondola cable, killing twenty skiers, many Italians were outraged when the pilot avoided Italian prosecution and then received a not guilty verdict in a North Carolina court-martial. Similarly, a U.S. military court once acquitted a sergeant who shot and killed a fifty-five-year-old Okinawan woman after he claimed he mistook her for a wild boar.34 And in the aftermath of the 1995 schoolgirl rape, Okinawans were incensed by provisions in the U.S.-Japan SOFA that allowed the military to deny the Japanese police access to the rape suspects until the issuance of a formal indictment.35

INERTIA

It’s been nearly two decades since the 1995 rape and the 1996 agreement to replace Futenma. In many ways, very little has happened. The military has returned some land, but many of the bases scheduled for return remain in operation. Futenma is still open and set to remain open until at least 2021. Construction of a replacement in Nago still faces intense protest and is moving very slowly, despite a new promise of $2.9 billion a year in Japanese government subsidies for the prefecture. Protests have grown and expanded islandwide. In Takae, a richly forested area in northern Okinawa that’s the site of the Marines’ Jungle Warfare Training Center, locals and their supporters have been protesting since 2007 against construction of six new helipads.36

Meanwhile, Okinawans have watched as military personnel continue to be involved in crimes and accidents on the island they are theoretically protecting. In the first sixteen years after the 1995 rape, there were reports of at least twenty-three more rapes and sexual assaults committed by U.S. military personnel in Okinawa.37 In 2000, for example, a drunk nineteen-year-old marine sneaked into an apartment and sexually assaulted a fourteen-year-old girl.38 In total, between 1972 (when Okinawa was returned to Japan) and 2011, the Okinawan prefectural government has documented 5,747 criminal cases involving GIs, including more than a thousand violent offenses. Over the same period, the prefecture documented 1,609 “incidents and accidents” ranging from speeding tickets to damage from military exercises, and more than a thousand aircraft-related accidents and forest fires. Between 1981 and 2011, the prefecture counted 2,764 traffic accidents, many related to drunk driving.39 The nongovernmental organization Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence has compiled a list of around 350 documented rapes, sexual assaults, and other crimes against women between 1945 and 2011. Since sexual assaults are especially prone to underreporting, there have likely been more crimes and accidents not included in the statistics.40

Crimes committed elsewhere in Japan have only further damaged the reputation of the military that’s ostensibly protecting all Japanese citizens. In 2002, the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk returned to the Yokosuka Navy base, south of Tokyo, after a deployment to support the war in Afghanistan. Within days, police forces arrested one sailor for assault and robbery, another for carjacking, and a third for drug smuggling.41

In 2012, the Marine Corps generated yet more opposition when it announced plans to move about two dozen MV-22 Osprey aircraft to Futenma. The hybrid plane/helicopter has a much-publicized accident record, leading to a demonstration that may have exceeded even the size of 1995’s protests, estimated at 85,000 people. A New York Times editorial described the deployment as “rubbing salt into an old wound.”42 Just days after the first Ospreys arrived, two sailors were arrested and later convicted for raping and robbing an Okinawan woman in a parking lot. Military officials imposed an 11:00 p.m. curfew and “core values training,” only for a series of new arrests to follow.43

In the face of continued Okinawan resistance, the Obama administration finally appeared to soften its position in 2012. Rather than demanding a replacement base before it would close Futenma, the administration announced it would move some nine thousand marines and around the same number of family members off Okinawa, whether the military had a replacement base or not. About five thousand marines would move to Guam; the other four thousand or so would disperse to bases in Hawaii, Australia, and Southeast Asia.44 Japan agreed to provide $3.1 billion of the moving costs.45 At the same time, though, the Marine Corps announced that it would actually increase its forces in Okinawa to nineteen thousand ahead of the planned withdrawal.46

While little has happened in terms of closing Futenma and moving marines off Okinawa, what has happened under the 1996 agreement is a lot of new base construction. Specifically, Japan had already agreed to fund $2 billion in new housing as part of a plan to replace 1,473 homes at Kadena Air Base and 1,777 units at Camp Foster. (On top of this, U.S. taxpayers funded a $95 million project to renovate 560 multifamily homes and expand parking to a very high 2.5 spaces per unit at Kadena.) “So what started out as a response to a rape ended up being a major housing construction program, providing new homes at no cost” to the United States, notes Mark Gillem.47

Government officials and military personnel in the United States, Japan, and Okinawa frequently express frustration at the slow pace of closing Futenma and moving marines off the island. Then again, for many of them, the status quo hasn’t been so bad. The military still has its bases and lots of new housing. Japanese officials have shelled out billions of Japanese taxpayer dollars, but much of it has gone to Tokyo construction firms and other Japanese companies. Landowners, politicians, a few thousand base employees, and some businesses in Okinawa continue to benefit. Kevin Maher is gone, but bureaucrats like him on all sides have steady employment discussing the Okinawa issue. As my student group reached the end of our two-week exploration of bases, I increasingly wondered if many are more than content just to keep things as they are.

QUID PRO QUO

The uneven distribution of local benefits helps explain the complex politics of the base issue in many host communities. While almost all Okinawans want to see Futenma removed, for instance, opposition to other bases on the island is far from universal. Most of the landowners to whom the Japanese government pays rent support an ongoing U.S. presence,48 and many business owners who benefit from sales to U.S. personnel are also supportive. A union that represents base employees likewise favors the bases, though other labor unions in Okinawa make up an important segment of the protest movement.

During my first visit to the prefecture, Okinawa International Professor of Politics Manabu Sato told our student group that Okinawa ultimately accepts the bases because, given the island’s isolation, small size, and lack of natural resources, it needs the government aid they bring. The Japanese government has thus been pouring tens of millions into Okinawa as a “bribe” to make them accept the Futenma replacement, he explained.

The base expert Alexander Cooley details how the system works. “After reversion in 1972, Tokyo increased the rent it paid to the more than 30,000 private U.S. base landowners by 600 percent,” easily exceeding market value. Then, writes Cooley, “construction companies and their subcontractors colluded with the prefecture and Tokyo to apportion and undertake hundreds of … new public works and development projects.” “This quid pro quo” of economic investment in exchange for local acquiescence to the U.S. presence “has since become institutionalized,” says Cooley, “and remains a hallmark of Okinawa’s relations with the Japanese mainland.”49 When the Japanese government agreed to U.S. requests in 1978 to begin paying the salaries of thousands of Japanese civilians working on U.S. bases through what became known as the “sympathy budget,” it further solidified Okinawan support at a time when bases’ direct economic impact was declining.

Since the growth of antibase protest following the 1995 rape, the system has only expanded. The “militancy and opposition to the bases,” explains Cooley, “have driven Tokyo to develop and institutionalize a comprehensive system of fiscal transfers, public works funds, and targeted payments to key island actors.” With the help of a “permanent and well-funded state bureaucracy” in Tokyo, “these sizable transfers have established a political economy of base-related compensation that ultimately assures that a slight political majority in Okinawa continues to support the U.S. presence, albeit tacitly.”50

At the same time, many acknowledge that much of the aid has gone toward building what Sato called “useless public facilities,” such as little-used recreation centers and unnecessary monuments. Okinawan politicians accept the money because it means construction jobs, Sato said. But then Okinawa is stuck with the maintenance costs for the facilities. Meanwhile, much of the money ends up back in Tokyo, he added, because it’s the big Tokyo construction firms that get most of the contracts.51

While Japan has spent an estimated $70 billion to raise Okinawa’s level of development to Japanese standards since the end of the U.S. occupation in 1972, per capita income there remains the lowest among Japan’s 47 prefectures, at around 70 percent of the national average. The unemployment rate remains the highest nationwide, at 7.5 percent.52 People are realizing “this money is not to build a sustainable economy,” said Sato. In rural northern communities of Okinawa, where most of the U.S. training bases are found, government spending is creating a “serious dependency problem.”

HIDDEN COSTS

The immense amounts spent by Japan on the “sympathy budget” and other support for U.S. bases make it particularly ironic that Kevin Maher described Okinawans as “extortionists”: U.S. negotiators themselves have long pressed the Japanese government for ever larger subsidies to the U.S. military presence in East Asia. Since at least 1972, Japan has generally paid more than any other host country to support the U.S. base and troop presence. Over time, those payments have added up to many tens of billions of dollars.

Although the 1972 deal that returned Okinawa to Japan was widely dubbed “reversion,” Japan secretly agreed as part of the negotiations to abide by quotas on textile exports to the United States and to pay as much as $685 million for Okinawa’s return. The payments included the cost of buildings and utilities returned to Japan and the expense of removing nuclear weapons from the island. (Another secret agreement allowed the reintroduction of nuclear weapons in emergencies.) The Japanese government also agreed to help prop up the weakening value of the dollar by depositing $112 million in New York’s Federal Reserve Bank for twenty-five years, interest free. And the government paid another $250 million over five years for base maintenance and Okinawan defense costs. As Gavan McCormack, an expert on U.S.-Japan relations, puts it, “the ‘return’ of 1972 was actually a purchase, and Japan has continued ever since to pay huge amounts.” These are “in effect a reverse rental fee, by which the Japanese landlord pays its American tenant.”53

Today, Japanese sympathy payments subsidize the U.S. presence at an annual level of around $150,000 per service member.54 For 2011 alone, Japanese taxpayers provided $7.1 billion, or around three quarters of total basing costs.55 In addition to agreeing to pay $6.09 billion to help close Futenma and move marines off Okinawa, the Japanese government agreed to contribute around $15.9 billion toward a larger set of transformations involving bases in Okinawa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and Iwakuni, Japan.56 As in 1972, Japan is effectively paying to get its land back.

Japanese taxpayers have also spent nearly $1 billion to soundproof civilian homes near noisy U.S. air bases in Okinawa, and millions more in damages assessed in noise pollution lawsuits. Because of favorable basing agreements, the U.S. military generally doesn’t have to pay for environmental cleanup in Japan, South Korea, or elsewhere. These costs also come from citizens’ taxes, further reducing the net value of any local benefits. Most U.S. and conservative Japanese officials would say that Japan has simply been paying the United States to provide security. While this argument may have been plausible during the Cold War, it seems harder to sustain today. Although there is real public fear of China, especially over tensions in the East China Sea, China’s military power still does not rival that of the United States. Japan’s so-called Self-Defense Forces are also one of the world’s most powerful militaries, even though Japan’s U.S.-drafted constitution renounces war and insists that armed forces “will never be maintained.” The country regularly ranks among the world’s top military spenders (fifth in 2012, eighth in 2013).57 Since 2001, Japan has provided both financial contributions and “boots on the ground” in Afghanistan and Iraq. And Japan apparently feels secure enough in its self-defense to have a foreign military base of its own in Djibouti, the country’s first since World War II.

“WE DON’T NEED MARINES IN OKINAWA”

Gradually, a growing number of military analysts have started to question the U.S. base presence in Okinawa—not on political or social grounds, but on purely military ones. The growing range and accuracy of Chinese and North Korean missiles have led many to conclude that bases so close to the Asian continent are so vulnerable to attack as to be of little value.58

More profoundly, analysts across the political spectrum are increasingly beginning to question the underlying justifications and rationale for the bases. As long as the United States has had bases in Okinawa and Japan, the primary justification for their existence has been that they ensure security for the United States, Japan, and the region. Initially, it was said that the bases helped contain and deter Soviet expansionist desires. Since the end of the Cold War, many have simply substituted China and North Korea for the USSR in the containment/deterrence framework. But North Korea is a small, impoverished nation, possibly on the verge of collapse. And while China’s military power has grown in recent years, it doesn’t approach that of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. What’s more, placing bases and troops on another country’s doorstep can be seen as an aggression in its own right, triggering exactly the kind of military response the strategy is supposedly designed to prevent.

Even within the context of containment and deterrence, the U.S. presence in Okinawa hardly looks like an optimal setup. Many now agree, for example, that the Marines’ presence in Okinawa—including the controversial Futenma base and its debated replacement—likely has little deterrent effect. Barry Posen, who was a Pentagon official in the Bush administration, has said that with the large Air Force and Navy forces at Okinawa’s Kadena Air Base and on mainland Japan, the withdrawal of the marines would see “no change in deterrence.” Posen added that he “cannot see what role the Marine Corps might play in military actions” that conceivably might take place in the region.59 Former Democratic House representative Barney Frank agreed, saying, “15,000 Marines aren’t going to land on the Chinese mainland and confront millions of Chinese soldiers. We don’t need Marines in Okinawa. They’re a hangover from a war that ended 65 years ago.”60

And there often haven’t even been fifteen thousand marines in Okinawa, the number frequently cited by proponents of the status quo. During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, thousands of them deployed from Okinawa, decreasing troop levels by one quarter to one third from prewar averages.61 If Okinawa-based Marines are so critical to deterrence, how could the military afford to let them leave?

Marines in Okinawa also don’t have the transportation necessary to get involved in significant numbers during an emergency. To deploy, marines rely on Navy transportation vessels harbored in Sasebo, Japan. During a 2013 drill simulating a response to China’s seizing contested territory, such as the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, marines relied on a vessel based in San Diego to transport troops and weaponry.62 The Marines’ controversial Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft doesn’t have the range to transport troops to the Senkaku/Diaoyus without in-air refueling; and with just twenty-four Ospreys in Okinawa, the Marines can send fewer than six hundred troops at most in a single deployment.63 If the Marines can’t operate independently and speedily from Okinawa, what kind of regional deterrent force are they?

The fact is that, in many ways, the Marines’ entire presence in Okinawa has little to do with military strategy or security. Partly, they are attached to the island because it provides a great place to train. (When not deployed at war, much of what troops do is train.) The Marines don’t want to relinquish facilities like Okinawa’s huge Jungle Warfare Training Center, which was, until recently, the only jungle training center in the military. The Marine Corps’ institutional attachment to the island also plays a significant role. Given the high casualties suffered in the Pacific War’s deadliest battle, Okinawa has a hallowed place in the history of the Corps, so the Marines have long considered the territory to be “theirs.” They simply don’t want to give it up.

The Marine Corps also hasn’t wanted to give up Okinawa because in recent years many marines have feared for the service’s very existence. During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Marine Corps has fought much like the Army. The Marines’ last amphibious landing was more than half a century ago, in the Korean War, leading many to question why the military has an amphibious armed service that’s effectively a second army. Giving up bases in Okinawa, and with them the idea that the Marines are necessary to maintain peace in East Asia, would mean the Marine Corps could lose one of its three main combat divisions.64 “The Marines are so afraid because if the decision is made to move them,” explained the former Pentagon official Ray DuBois, the next decision may be “that those marines will disappear.” Losing some of the total marine troop strength would mean losing money in the Pentagon budget, raising more questions about whether the service needs to exist at all. Even the idea proposed by some senators of relocating marines from Futenma to available space at the Air Force’s Kadena Air Base is anathema to the Marine Corps, given that such a move would cede power to another of the armed services.

More broadly, U.S. officials see removing bases and troops from Okinawa as weakening the U.S.-Japanese military alliance, whereas successive presidential administrations have been trying to deepen bilateral military cooperation. Some suggest that U.S. officials have been trying to turn Japan into something of the “Great Britain of Asia”—and that many Japanese officials are more than happy to assume that role, given the power and financial benefits it has brought Britain.65 U.S. officials would like to use Japan’s military as a subordinate force within a global military architecture that’s increasingly relying on the incorporation of allied armies into a U.S.-controlled system. In the process, U.S. leaders hope to keep Japan locked into its position as a Cold War–era client state during a new era when the rationale for maintaining Cold War alliances has disappeared, when Japan could potentially assert more independence, and when U.S. political, economic, and military control in East Asia is being challenged by China and other rising powers. Holding on to bases in Okinawa becomes a way to try to hold on to a Japanese puppet and, with it, U.S. political-economic dominance.

Temporarily putting aside questions about the wisdom, efficacy, and morality of this strategy, its financial costs alone should raise serious doubts. Remember that despite large sums contributed by the Japanese government, U.S. taxpayers are likely paying $150 million to $225 million more per year to keep around fifteen thousand marines in Okinawa compared to basing them in the United States. Basing U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force personnel in Okinawa and elsewhere in Japan is even more expensive for the U.S. government compared to domestic basing.66 The total additional cost to U.S. taxpayers to maintain 109 base sites and more than fifty thousand troops in Japan could easily top one billion dollars a year. Ironically enough, in addition to those being extorted in Okinawa and Japan, Americans are being extorted too.

“No Dal Molin” protest against the construction of a new U.S. Army base in Vicenza, Italy.