During one of my research trips to Vicenza, I heard about the death of Private First Class Russell Madden, a member of the 173rd Airborne brigade that’s split between Vicenza and Germany. Madden had died in Afghanistan just a few days earlier, on June 23, 2010, from blast injuries sustained when a rocket-propelled grenade tore through his vehicle.

I regularly followed the deaths of troops at war in Afghanistan and Iraq, but when I learned more about Madden’s life his death struck me as particularly poignant. He grew up in Bellevue, Kentucky, a town of six thousand, where he was a high school football star. At twenty-nine, he enlisted in the Army because he needed health insurance to cover treatment for his four-year-old son’s cystic fibrosis. “He joined because he knew that Parker would be taken care of no matter what,” Madden’s sister said.

For several years I hoped to speak with a member of Russell Madden’s family. Finally, I found his mother, Peggy Madden Davitt. She told me that Russell had signed up for the Army soon after his son was turned away by the Mayo Clinic, where the family had hoped to get treatment. “No one will ever send my son away again,” she remembers Russell saying.

After Russell’s death, Peggy received a standard condolence letter from President Obama. “I am deeply saddened to learn of the loss of your son,” the letter said. “Our Nation will not forget his sacrifice, and we can never repay our debt to your family.” Turning over the presidential stationery, Peggy addressed a response to President Obama. “If my son had found a decent employer and sufficient health insurance in this great land of ours,” she wrote, “my son would not have had to sacrifice his life for his son.” Peggy sent the letter back to the White House. She did not receive a reply.

Russell Madden’s story is a reminder of the life-and-death significance of the choices connected to our base nation. Unlike virtually all of the wealthy industrialized countries in which the United States maintains bases—Germany, Japan, South Korea, Britain, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Norway, and Belgium among them—the United States does not guarantee health care for all its citizens. The idea of doing so is often dismissed as too expensive. Meanwhile, the nation spends immense sums every year supporting a global base infrastructure largely born of a world war and a cold war that ended decades ago.

Health care, of course, is not the only area in which we have made a questionable trade-off. During my travels, I was struck by the impressive public transportation systems found in some of the countries hosting our bases, such as Germany, Japan, and South Korea. Even in Italy, where many often criticize the train system and the public sector, the speed and efficiency of public transportation options are far superior to those in the United States. Initially, I included this observation in my notes as an aside, distinct from the subject of my research. It was only later that I realized the interrelated nature of the two phenomena—the U.S. overseas base infrastructure and host countries’ public transportation infrastructures. While countries such as Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Italy have spent large amounts supporting U.S. bases on their soil, their military spending has been accompanied by impressive investments to improve their citizens’ lives. Meanwhile, U.S. investments in bases have come at the cost of decades of neglecting transportation, health, education, housing, infrastructure, and other human necessities. Think about what just half of the $70 billion or more going into the base world every year could do to improve the lives of Americans.

MAINSTREAM DEBATE

When I began this book almost six years ago, the issue of overseas bases was on the margins of political discourse. Today, it is increasingly moving toward the center of debates about the Pentagon budget and the shape and function of the U.S. military in the twenty-first century. The tremendous costs of maintaining such an unparalleled collection of bases abroad have made closing foreign bases one of the rare ideas that draw support from across the political spectrum, including liberals, conservatives, libertarians, far-right Tea Party members and far-left Occupiers, and moderates in both parties.

In recent years, for example, conservative Republican senator Tom Coburn and the liberal Center for American Progress proposed cutting troop deployments in Europe and Asia by a third to save $70 billion by 2021.1 Others, like Democratic senator Jon Tester and retired Republican Texas senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, have called for moving overseas bases and military spending back home. Hutchison proposed a “Build in America” policy to protect “the future security posture of U.S. military forces and … the fiscal health of our nation.”2

The libertarian Ron Paul made the closure of overseas bases a major platform of his 2012 presidential campaign. “We have to have a strong national defense, but we don’t get strength by diluting ourselves in 900 bases in 130 countries,” he said in a Republican debate. “I want to bring the troops home.”3

Still others, like the New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, argue that investing in disease research, education, and diplomacy would do more to protect U.S. citizens than bases in Germany. “Do we fear,” he asked in 2011, “that if we pull our bases from Germany, Russia might invade?”4 (Russia’s recent annexation of the nearly defenseless Crimea doesn’t make this far-fetched scenario any more likely; Germany, by itself, has nearly as many high-quality tanks as Russia, to say nothing of the rest of NATO.)

The once wonkish topic of overseas bases has even become material for prime-time comedy. “Europeans get full health care coverage, a generous pension, day care, long paid vacations, maternity leave, free college, and public transportation that doesn’t smell like pee,” Bill Maher has joked on his HBO show Real Time. “Whereas our tax dollars go towards military bases in Germany, subsidies to oil companies, building bridges to nowhere, wars, and putting half of Cheech and Chong in prison.”5

Even within the military, growing numbers are questioning whether the country can afford hundreds of bases abroad. “We’ve got too many daggone bases,” the former commander of U.S. Air Forces in Europe General Roger Brady has said publicly. “There’s big money to be saved by closing them.”6

At the same time, more base experts of all political persuasions are concluding that the days of maintaining lots of overseas bases—especially sprawling “Little Americas”—are numbered. They see that technological advancements in the air and at sea now allow the rapid movement of military forces and power directly from the United States, decreasing any strategic value for permanent foreign bases. The former Pentagon official Ray DuBois and others in the George W. Bush administration have pointed to a Joint Chiefs of Staff study showing that, in most cases, the time difference between deploying troops to potential war zones from bases in Europe and deploying them from the east coast of the United States is either insignificant or completely nonexistent.7 A RAND study explains, “Ground forces based in Europe do not provide a significant deployment benefit to other theaters … If a situation is time-sensitive, lighter units can be airlifted from [the United States] in a time span comparable to those for European-based units.”8 A congressionally mandated National Defense Panel has suggested maintaining forces based in the United States ready to “project significant power” overseas “within hours or days, rather than months.”9

Sustaining large numbers of forces in any lengthy war or peacekeeping operation far from the United States would still require significant basing facilities, most likely in allied nations. But as far as quickly sending military forces abroad in an emergency is concerned, overseas installations are simply not necessary. Thanks to fast airlift and sealift, long-range bombers, in-air refueling capabilities, eleven aircraft carriers, a large submarine fleet, other elements of the world’s most powerful naval and air forces, and large numbers of domestic bases, the U.S. military already has the capability—even without any bases abroad—to deploy more military power faster and over longer distances than any other military on earth, by far. The nation’s current basing network and its broader military strategy are not the only option.

DETERRENCE?

The primary argument in favor of maintaining bases and troops overseas has long been that they keep the peace and make the United States and the world safer and more secure. After six years of working on this book and fourteen years studying the issue, I have a simple response to that assertion: prove it.

For decades, supporters of the overseas status quo have simply proclaimed the security benefits as a self-evident truth. Rarely has anyone forced them to support their claims. Scholarly debates about the effectiveness of various strategies of military deterrence—the threat to use force to prevent another power from using force—have raged for decades without end. Considerable research has led to what one review summarized as “widely different results and little or no consensus on a set of variables that predict [effective] deterrence.”10 Others are even more critical, concluding, for example, that “deterrence emerges as a shabby parody of a scientific theory. Its fundamental behavioral assumptions are wrong. Its basic terms are ill defined. It is used in inconsistent and contradictory ways. Commonly cited examples of effective deterrence are often based on flawed assumptions of history, sometimes reflecting ignorance, sometimes deliberate misrepresentation.”11

Some analysts ardently support the validity and continued relevance of deterrence theory.12 But almost all of their research analyzes deterrence in the face of immediate threats (like troops massed at a border, ready to invade). There has been little investigation of the effectiveness of long-term deterrence, of the kind supposedly provided by U.S. bases overseas.13

This is not to say that overseas bases never contribute to security. The intellectually honest truth is that evaluating the effect overseas bases have on security is extremely difficult. Often, if not always, people come down on one side or another based not on evidence but on a set of underlying beliefs and assumptions about military force and foreign policy.

The major assumption underlying a belief in the value of overseas bases and foreign military presence is the idea that if France and Britain and the United States had aggressively confronted Hitler in the 1930s rather than pursuing a policy of “appeasement,” World War II could have been averted. Many treat this counterfactual scenario as the lesson of World War II. But given that history doesn’t allow for do-overs or scientific controls, there’s no way to prove conclusively whether that assumption is true or false.

Many have made similarly questionable arguments in stating that the outcome of the Cold War proves the effectiveness of deterrence. Demolishing such conclusions, the international relations scholar Steve Chan writes:

Was the U.S. deterrence against the USSR effective? That Moscow did not attack Western Europe might have been because of the effectiveness of this U.S. deterrence. It could also be that Moscow never had any intention of launching such an attack, or that it might have been dissuaded from carrying out such an attack by its economic weakness, dissension among its leaders, concern for a challenge from China, or some other reason. Thus, one needs to guard against spurious inferences, giving credit to deterrence for keeping peace and stability when this policy does not quite deserve such credit.14

Even if the assumptions about pre–World War II history or about the Cold War were hypothetically correct, these singular cases would not come close to providing conclusive evidence that overseas bases ensure security across time and place. One could make an equally emotionally resonant argument that if the United States had not occupied the Muslim holy land of Saudi Arabia with military bases and troops after the first Gulf War, al-Qaeda’s attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, could have been averted. Like the Hitler appeasement argument, this may be true, but it is equally unknowable.

The confrontation between North and South Korea is another helpful case. Proponents of a large overseas U.S. military presence often argue that U.S. forces in South Korea and in other parts of Asia have deterred North Korea from invading South Korea and kept the peace in East Asia. That may be so. But there may be an equally strong, if not stronger, case to be made that the presence of U.S. troops in South Korea has prolonged the conflict and a war that has never technically ended. From North Korea’s perspective, having the world’s most powerful military on its doorstep seems like good reason to build up its military power—and a nuclear capability—rather than working to de-escalate the conflict. For China, there’s similarly good reason to prop up North Korea, given that the dissolution of the North and reunification of Korea could put tens of thousands of U.S. forces—already on the Asian mainland—onto the Chinese border.

Rather than keeping the peace and making the Korean peninsula safer, U.S. bases may be contributing to a state of heightened tension that has made the outbreak of war more likely and peace more difficult to achieve. In fact, there’s a reasonable argument that it’s been in the interest (conscious or unconscious) of some U.S. officials to maintain a state of war, to have a justification for maintaining troops and bases in Korea and thus on the Asian mainland.

HARM

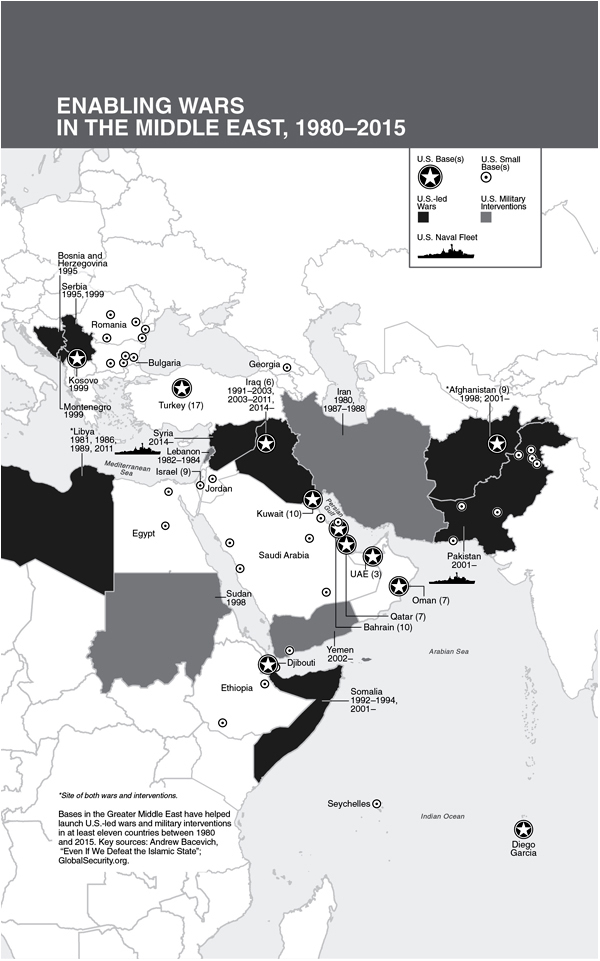

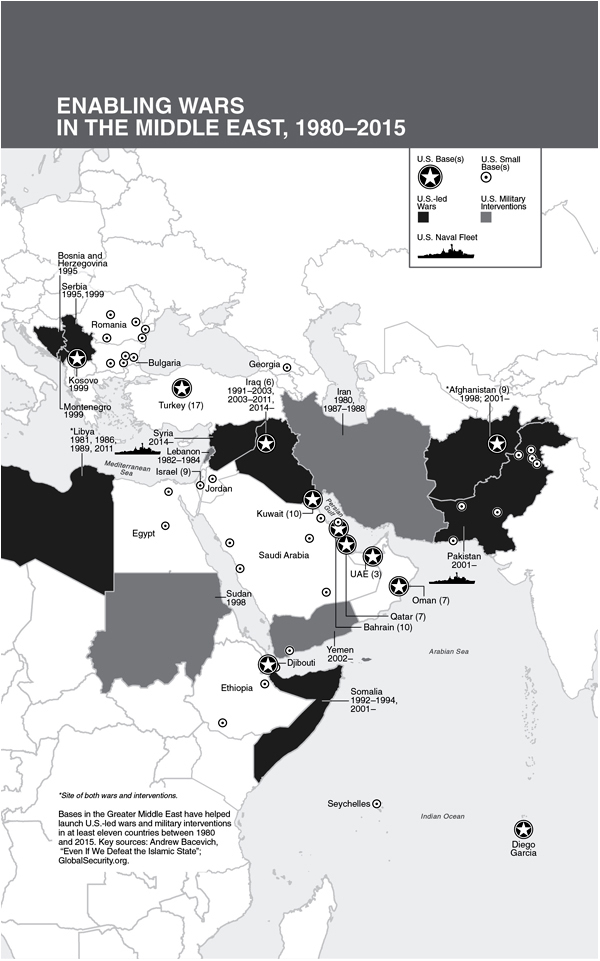

While there is no evidence to say conclusively that overseas bases make the United States or the world safer in a military sense, we have seen abundant evidence that bases abroad are harming the safety, security, and well-being of millions of people—ranging from the locals living near bases to the military personnel, family members, and civilians living and working on them. It’s also indisputable that U.S. bases and troops abroad have consistently generated opposition and anger. In some extreme but far from isolated cases, bases and troops have either spawned violence against Americans or provided convenient targets, as in attacks on marines in Lebanon in 1983 and on the USS Cole in Yemen in 2000. The U.S. occupation of Saudi Arabia was a major recruiting tool for al-Qaeda and part of Osama bin Laden’s professed motivation for the 9/11 attacks.15 Research has shown that U.S. bases and troops in the Middle East have been a “major catalyst for anti-Americanism and radicalization” and that there has been a strong correlation between a U.S. basing presence and al-Qaeda recruitment.16

The rapid spread of lily pad bases today risks arousing more opposition, despite their small size. Intimately linked with the deployment of special operations forces to nearly every nation on earth, the lily pad strategy and the new way of war that it represents appear to be part of a troubling and dangerous expansion of the Cold War–era “forward strategy.”17 After World War II, the forward strategy transformed U.S. ideas about security, defense, and threats to the United States. As the base expert Catherine Lutz put it, the United States moved from being “a nation suspicious of standing armies to one whose military patrols the globe in all of its corners, twenty-four hours each day.”18 Lutz wrote those words shortly before 2001; since then, thanks to the global “war on terror,” the military’s reach has grown even further, with troops and U.S. military facilities located in almost every country in the world.

As the journalist Robert D. Kaplan has said, the U.S. military now stands ready “to flood the most obscure areas of [the earth] with troops at a moment’s notice.” When Kaplan visited U.S. troops at lily pad bases and other obscure and remote locations around the globe, he heard a consistent refrain: “Welcome to Injun Country.”19 These words, and the frequent descriptions of lily pads as “frontier forts” hosting a “global cavalry,” are deeply troubling—for their racial overtones, for their invocation of a Manifest Destiny–like “civilizing” mission, and for the suggestion of ever-expanding military operations. One doesn’t go to “Injun Country” just for the scenery. One goes looking for Injuns.

On Independence Day in 1821, John Quincy Adams, then the secretary of state, warned of the dangers of looking for enemies abroad. America, he said, “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” If it were to do so, Adams cautioned, the country “would involve herself, beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom.”20

For Adams, this did not mean neglecting other nations and the causes of freedom and independence. Rather, he said, America should support those causes, but through “the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example” rather than military power. If the country did involve itself in foreign wars, Adams said,

The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force. The frontlet upon her brows would no longer beam with the ineffable splendor of freedom and independence; but in its stead would soon be substituted an imperial diadem, flashing in false and tarnished lustre the murky radiance of dominion and power. She might become the dictatress of the world: she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.21

For almost two hundred years, the United States has increasingly failed to heed this advice. Force has become one of America’s fundamental policy maxims. As Eisenhower would explain 140 years after Adams, military power has become a key organizing principle for the country’s political and economic systems. And as Adams suggested, the luster of global domination and power has proved false and self-defeating.

It is not too late for the country to heed Adams’s words. And beyond words, the country would do well to note the agenda Adams laid out as president. In contrast to the expansionist visions of Presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson, who preceded and followed him, Adams proposed broad improvements to the nation’s infrastructure of roads and canals; investments to support science, invention, and enterprise; and global efforts toward “the common improvement of the species.” He also refused to sign a treaty that would have dispossessed the Creek nation of its lands in Georgia. Unfortunately, Adams’s political instincts never matched his ideas and his ideals, and much of his agenda was never implemented. But we still have a chance today to make the investments in transportation, science, education, entrepreneurship, energy, and housing that have been neglected while trillions of dollars have been poured into unnecessary wars and military bases abroad.22

LOOKING FOR FIRES

Since the end of the Cold War, part of the problem has been that, lacking a superpower rival, the U.S. military has gone looking for new monsters and new enemies. This resembles what some call the “firefighter problem”: in an era when there are fewer and fewer fires for firefighters to deal with, they have tended to look for other things to do. Most firefighters today spend little of their time actually fighting fires, while their help in medical emergencies and other work often comes at great and inefficient expense.

That the military, too, has looked for new things to do is in many ways understandable. Few of us have the vision and strength, whether as individuals or as part of larger institutions, to say that we are not needed or that our roles should be reduced or eliminated. (The March of Dimes had a similar problem after the eradication of polio, the disease the organization was founded to combat.) But this understandable inertia does not justify the massive waste and suffering that overseas bases inflict.

The global basing transformation initiated in the early days of the Bush administration was supposed to reduce the collection of bases and move the remaining ones into more strategic positions. Instead, thanks to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the boom in base construction around the world, our base presence abroad has resembled a game of Whac-A-Mole: every time a base has been closed down, another base (or millions in new MilCon spending) has tended to pop up somewhere else.

In even more complicated ways than major weapons systems, overseas military bases are the true incarnation of President Eisenhower’s worst nightmares about the military-industrial complex.23 The establishment of overseas bases has created entire social worlds, with thousands of people and corporations that have become economically, socially, bureaucratically, psychologically, and, as Eisenhower said, even spiritually dependent on the continued operation of those worlds—just like fire departments but on a much larger scale. Even worse, these bases tend to entrench themselves in local communities and host nations, creating yet more dependence around the world.

As the Senate’s Vietnam-era investigation of overseas bases showed decades ago, once overseas bases are established, they become difficult to close whether they’re needed or not. Indeed, the base world is a perfect, if horrifying, symbol of how the military-industrial complex is like Frankenstein’s monster, taking on a life of its own and gaining “unwarranted” influence24 thanks to the spending it commands. This has been true since the days of Eisenhower, but it’s become even more the case since the start of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In the decade after September 2001, Pentagon budgets roughly doubled. Military spending reached levels not seen since the height of the Cold War, nearly equaling the rest of the world’s military spending combined25—despite the absence of another superpower and facing an al-Qaeda threat numbering only in the thousands of militants and with very limited ability to attack the United States. Given such profligacy, there should be little surprise that bases in Afghanistan and Iraq became so luxurious and laden with “ice cream” they made some soldiers cringe. There should be little surprise that they became the sites for tens of billions of dollars lost to waste, fraud, and abuse.

The danger of bases taking on lives of their own of course extends beyond the wasted money and national resources. Unlike firefighters, when bases abroad look for things to do, the consequences extend far beyond potential waste and inefficiency. In many ways, instead of providing security, overseas bases are often helping to make the world a more dangerous place. In South Korea, for example, military leaders are planning for troops’ housing needs a decade or more in advance,26 with seemingly no thought that the Korean conflict might end and make these bases unnecessary. One wonders whether such ingrained assumptions have limited U.S. peacemaking efforts and the prospects for peace between the Koreas. Likewise, U.S. officials may say that building new bases in East Asia (on top of hundreds of existing ones in the region) is defensive and will help ensure the peace. But how do those bases look from China’s perspective? A base that’s reassuring for one power can look like a threat to another.

Whatever the rhetoric of ensuring peace and spreading democracy, overseas bases are meant to threaten. They are designed to demonstrate power and dominance. But it’s far from clear that demonstrating power and dominance makes the United States or the world any safer or more secure. Remember how the Kennedy administration reacted when the Soviet Union began installing nuclear weapons in Cuba—its only base in the Western hemisphere—at a time when the United States and its allies already had hundreds of bases, many stocked with nuclear weapons, surrounding the Soviet Union. The world then came closer to a nuclear conflict than at any other point during the Cold War.

Recently, Russia publicly announced its intention to build four new overseas bases—in the Seychelles, Singapore, Nicaragua, and Venezuela—to complement the nine foreign bases it already possesses. “We need bases for refueling [our aircraft] near the equator, and in other places,” said Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu in February 2014. He also announced Russia’s intention to sign agreements in the four countries to allow for increased port visits and the use of airfields. Additionally, Russia is in the process of increasing the size of its presence at bases in Tajikistan, Belarus, and Kyrgyzstan.27

As Russia’s plans show, the creation of U.S. bases overseas risks encouraging other nations to boost their own military spending and build their own foreign bases in what could become escalating “base races.”28 Given Russia’s professed desire to increase its influence and stature worldwide, building new Russian bases abroad would be an unsurprising move, especially given recent U.S. attempts to use base construction, training, exercises, and other military activities to deepen its influence in Africa, Latin America, eastern Europe, and East Asia. China seems likely to try to follow suit, in Africa and the Indian Ocean in particular.29

Bases near the borders of China and Russia are especially dangerous as they threaten to fuel new cold wars. (Some say these are already under way.) Quite in contrast to the claim that overseas bases increase global security, we can see how they lead to growing international tensions and a greater risk of military confrontation.

For the United States, overseas bases have appeared to provide protection, safety, and security. They have appeared to hold out the promise of never having to fight a world war again. Instead, these bases have in many ways damaged national security. By making it simpler to wage foreign wars, they have made military action an even more attractive option among the foreign policy tools available to American policymakers, and they have made war more likely. (The rise of lily pad bases only deepens this problem, since a major part of their appeal for military officials is the flexibility they provide in applying military force without restriction.) The disastrous outcomes of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have created widespread public opposition to large-scale U.S. intervention and warfare—but as others have pointed out, when all you have in your foreign policy toolbox is hammers, everything starts looking like a nail.30

CHANGE

Today, there are some encouraging signs that the base nation is shrinking, thanks in part to Pentagon-wide budget cuts. While it remains unclear whether the military will fully withdraw its bases and troops from Afghanistan and Iraq, the withdrawal of most U.S. forces has been a positive development, albeit amid continuing devastation and violence in both countries. The closure of large numbers of Cold War–era bases and the removal of tens of thousands of troops from Europe and, to a lesser extent, East Asia since the George W. Bush administration initiated its Global Posture Review have continued a much-needed drawdown begun after the dissolution of the Soviet Union but halted prematurely in the mid-1990s. The Pentagon is currently undertaking a “European Infrastructure Consolidation Review” to eliminate unnecessary facilities as part of plans to cut forces by a further 15 percent in Europe by 2023.31 European Command commander General Philip Breedlove has said, “There is infrastructure I believe we can still divest.”32

Among the armed services, the Navy has acknowledged having unnecessary bases and the Air Force has said it has “a lot of excess infrastructure” worldwide, according to its deputy chief of staff for logistics, installations, and mission support. The Air Force has a “20/20” program to eliminate 20 percent of its global infrastructure footprint by 2020 and says it is more than halfway to its goal. General Judith Fedder has said the service “could make better use of [its total] infrastructure if we could close installations.”33

The Army estimates having 10 to 15 percent excess base capacity in Europe and 18 percent worldwide. Assistant Secretary of the Army Katherine G. Hammack has said, “In today’s fiscally constrained environment, the Army cannot afford to keep and maintain excess infrastructure and overhead.”34 The Army’s highest-ranking officials have told Congress that a failure to close unnecessary facilities is an “empty space tax” wasting “hundreds of millions of dollars per year.”35

As Army officials acknowledge, the Pentagon’s plans to continue cutting the total size of the armed forces should make closing superfluous bases all the more important.36 And with so much extra domestic infrastructure—the Army and Air Force both have around 20 percent excess base capacity in the United States37—there’s plenty of room to bring troops home.

Closing Cold War bases built for a much larger military would lead to both immediate and long-term savings. The possibility of canceling billions in base construction, operations, and maintenance contracts is a good reminder that there are immediate savings available by reducing troop deployments and bases abroad. As we have seen, bringing troops and base spending back to the United States will mean stemming the leakage of money out of the U.S. economy and ensuring that economic spillover effects remain at home. In many cases, too, host nations will actually pay us for infrastructure we vacate. When we leave, we should assist in the work of cleaning up the environmental damage we caused; beyond that, we should properly consider residual value payments a peace dividend, rather than money to be funneled back into the base nation or the larger military budget.

The Cold War bases in Europe should be an obvious place to start with closures continuing progress the military has already made. The construction of new bases in Germany, such as the Army’s new billion-dollar hospital and half-billion-dollar European headquarters, is unnecessary and should be halted immediately. Bases in Latin America should have been among the first to be closed decades ago at the end of the Cold War. Closing Futenma and other bases in Okinawa and scrapping the ill-conceived and dangerous buildup on Guam and across the Asia-Pacific region are other important places to start; marines and other departing troops can and should move to bases with excess capacity on the west coast of the United States. Halting the construction of all new lily pads, no matter how small, is also critical.

Closing these and other bases may seem like a daunting task. Powerful institutional forces within the military, in the State Department, and among U.S. and local politicians and businesses will often align to block such change and maintain the status quo. On the other hand, compared to the challenge of closing domestic bases, closing overseas installations should be relatively easy. After all, U.S. politicians have few constituents abroad to whom they need be beholden. Prioritizing the interests of the country, its citizens, and the military itself by shutting down unnecessary bases is a realistic goal.

Closing bases overseas also offers a range of transformation opportunities. There are numerous models: former bases in Germany, Japan, and the United States have been turned into schools, public parks, housing developments, shopping malls, offices, business incubators, airports, and tourist destinations. Rather than simply handing over bases to host nations and leaving, Americans could collaborate with former base hosts, investing money and expertise in mutually beneficial ways. Throughout such transformation efforts, hiring preferences could be given to local base employees and veterans, helping them transition out of military life in the wake of base closures and military downsizing and making use of their skills and experience.

Beyond a onetime list of base closures, the Pentagon and Congress should create a regular review process to assess the need to maintain every base site overseas. The Pentagon should internally scrutinize every site on at least a yearly basis, and Congress should provide a second layer of scrutiny and oversight. Congress could also create incentives for the military to identify and carry out base closures abroad by ensuring that a proportion of these cuts would remain in each service’s budget rather than being ceded completely. Congress and the president should also change the tax code to ensure that contracts abroad do not offer tax advantages over contracts at domestic bases, thus eliminating a reason for contractors to favor keeping bases overseas.

Another encouraging sign has been the significant reduction in the size of military construction budgets in recent years. Still, the military and Congress can go farther when billions of dollars are still going to build new base infrastructure such as the new Army hospital and headquarters in Germany or to expand in places from Africa to Southeast Asia. Ending the profligacy of overseas MilCon would be an easy way to save money immediately in a time of budget cuts. Canceling contracts and declaring a moratorium on all new construction (except in cases where unsafe housing or workplace conditions might endanger lives) would provide immediate savings. Again, compared to the political difficulty of cuts and closures at domestic bases, these changes should be relatively easy to accomplish.

In the budget for fiscal year 2015, Congress took several critical steps to assert much-needed control over the MilCon process and Pentagon spending. Most important of all, Congress is attempting to prevent the military from building overseas without proper oversight. “None of the funds,” reads the year’s MilCon spending bill, “may be used to initiate a new installation overseas without prior notification to the Committees on Appropriations of both Houses of Congress.” Another provision of the law requires the Pentagon to alert Congress to any MilCon of more than $100,000 planned for military exercises, which has long been a way to build without congressional approval. To prevent military officials from wastefully spending MilCon money at the end of the fiscal year, Congress also prohibited the use of more than 20 percent of funding in the fiscal year’s last two months.38

Congress should make each of these provisions permanent, and there is more to be done. Congress should extend the Leahy Law, which cuts off aid to governments found to abuse their citizens’ human rights, in order to ensure that bases are not opened or maintained in undemocratic nations. Silencing criticism of human rights abuses as we maintain bases in countries like Bahrain makes the United States complicit in these states’ crimes. Maintaining bases in other undemocratic countries is equally counterproductive and makes a mockery of legitimate U.S. efforts to spread democracy and improve the well-being of people around the world. American bases have no business propping up repressive regimes.

Even in the most democratic of countries, the agreements that form the legal and political foundation for maintaining our bases are almost always secret, in whole or in part. In the interest of transparency and democracy, Congress should require that every status of forces agreement and base agreement on the books be published in its entirety. Many basing agreements are secret because they have been created as executive agreements not subject to congressional oversight. But base agreements are effectively treaties, and they should be subject to Congress’s approval.

Given the danger of foreign base races, the United States would be wise to use its current position of relative strength to propose and negotiate an international ban on foreign bases except under the strictest of circumstances and under the most transparent of conditions. Forgoing such a proposal now runs the risk of other countries’ acquiring bases in larger numbers and far closer to U.S. borders. A bases ban would need to allow for the creation of alliances and the establishment of foreign bases by explicit and transparent invitation when a country is under attack or facing a direct, credible threat. It could also make allowances for pre-positioning sites that could be monitored by UN inspectors and allow for the storage of military matériel around the world to be used only in UN-sanctioned peacekeeping operations.

A succession of empires and world powers through the centuries have amassed and subsequently lost most if not all of their foreign bases, either by force or divestment. Following in the footsteps of Portugal, Holland, Spain, and France, Britain had to shutter most of its foreign bases in the midst of an economic crisis in the 1960s and 1970s. The United States is headed in that same direction. The only questions are when and whether the country will close its bases and downsize its global mission by choice, or whether it will follow Britain’s path as a fading power forced to give up its bases from a position of weakness.

This is a large and politically challenging list of proposals. But proclaiming that things can never change is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Not making such proposals, not developing alternatives to the existing base nation, is the surest way to guarantee the continuation of a status quo that has hurt us all.