While the U.S. military was welcoming the families of American soldiers to overseas bases in the decades after World War II, it had very different plans for another group of families living on a small atoll in the middle of the Indian Ocean. In the late 1950s, Navy officials began developing a plan to build a new U.S. base on the British-controlled island of Diego Garcia, in the Chagos Archipelago. During talks with their British counterparts, Pentagon and State Department negotiators insisted that the Chagos islands come under their “exclusive control (without local inhabitants).”1

This tiny parenthetical phrase amounted to an expulsion order. Between 1968 and 1973, the two governments forcibly removed Diego Garcia’s entire indigenous population, deporting them to the western Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius and the Seychelles, twelve hundred miles from their homeland.

The exiled Chagossians received no resettlement assistance. Decades after their expulsion, they generally remain the poorest of the poor in Mauritius and the Seychelles, struggling to survive in places that outsiders know as exotic tourist and honeymoon destinations. The U.S. military, having claimed the Chagossians’ former home, has nicknamed Diego Garcia “the Footprint of Freedom.”

And Diego Garcia is not the only U.S. base with a sordid history of displacing indigenous populations. Military bases need land to exist, and throughout history, militaries have acquired such land through a variety of means. Sometimes, as in Germany and Japan, it comes with the aftermath of victory in war. Sometimes the land is bought or leased from locals or from a national government. But often, land has simply been taken.

STRATEGIC ISLAND CONCEPT

In a way, the idea for acquiring Diego Garcia dates to the winter of 1922, when eight-year-old Stuart Barber found himself sick and confined to bed at his family’s home in New Haven, Connecticut. Stu, as he was known, was always a solitary boy, and he sought solace in a cherished geography book. He was particularly fascinated by the world’s remote islands, and he developed a passion for collecting the stamps of far-flung island colonies. While the British-controlled Falkland Islands off the coast of Argentina was his favorite, Barber noticed that the Indian Ocean off the east coast of Africa was also dotted with islands claimed by Britain.

Thirty-six years later, Barber would once again be consulting lists of small, isolated colonial islands from every map, atlas, and nautical chart he could find. The year was 1958. Thin and spectacled, Barber was a civilian working in the Navy’s long-range planning office.

At this time of decolonization and Cold War confrontation between East and West, Barber and other officials in the growing national security bureaucracy were concerned about what would happen as colonized nations gained their independence. Postwar independence movements were vocally opposed to foreign military facilities, and U.S., British, and French bases were also increasingly criticized by the Soviet Union and the United Nations. U.S. officials were particularly worried that losing overseas bases would diminish American influence in the so-called Third World, where they predicted future military conflicts would likely take place.

“Within the next 5 to 10 years,” Barber wrote to the Navy brass, “virtually all of Africa, and certain Middle Eastern and Far Eastern territories presently under Western control will gain either complete independence or a high degree of autonomy,” making them likely to “drift from Western influence.”2 The inevitable result, Barber predicted, would be the withdrawal of U.S. and allied European military forces and “the denial or restriction” of Western bases in these areas.3 The Cold War’s “forward strategy” was premised on maintaining large numbers of bases and troops as close as possible to the Soviet Union, but Barber and others feared that the United States would soon face eviction orders across much of the globe.

Barber’s solution to this perceived threat was what he called the “Strategic Island Concept.” Barber had served as an intelligence officer in Hawaii during World War II and had seen the importance of having scores of Pacific island bases in defeating Japan. Island bases near hot spots in the “Third World,” he said, would increase the nation’s ability to rapidly deploy military force wherever and whenever officials desired. His plan was to avoid traditional base sites located in populous mainland areas, where bases were vulnerable to local opposition. Instead, he wrote, “only relatively small, lightly populated islands, separated from major population masses, could be safely held under full control of the West.”4

With the decolonization process unfolding rapidly, Barber argued that if the United States wanted to protect its “future freedom of military action,” government officials would have to act fast to “stockpile” basing rights, grabbing as many islands as possible as quickly as possible to retain territorial sovereignty in perpetuity. Just as a sensible investor would “stockpile any material commodity which foreseeably will become unavailable in the future,” Barber said, the United States had to find small, little-noticed colonial islands around the world and either buy them outright or ensure that Western allies maintained sovereignty over them. Otherwise the islands could be lost to decolonization forever.5 Once officials secured the islands, the military could then prepare them for base construction whenever future needs required.6

Barber told his superiors that the Navy should specifically look for small islands with good anchorages where the Navy could build airstrips, fuel storage tanks, and other logistical facilities capable of supporting minor peacetime deployments and major wartime operations. Island bases insulated from local “population problems” and “decolonization pressures” were the key to maintaining U.S. global dominance for decades to come.

Barber first thought of the Seychelles and its more than one hundred islands before exploring other possibilities in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. In and around the Indian Ocean alone, there were Phuket, Cocos, Masirah, Farquhar, Aldabra, Desroches, Salomon, and Peros Banhos. After finding all of them to be “inferior sites,” Barber settled on “that beautiful atoll of Diego Garcia, right in the middle of the ocean.” Its isolation made it safe from attack, yet it was still within striking distance of a wide area of the globe, from southern Africa and the Middle East to South and Southeast Asia.

Others in the national security bureaucracy quickly embraced Barber’s idea. In 1960, the Navy settled on Diego Garcia as its most important acquisition target. As Barber had recognized, the V-shaped island was blessed with a central location, a protected lagoon that offered one of the world’s great natural harbors, and enough land for a large airstrip.

Since it was first settled in the late eighteenth century, Diego Garcia and the rest of the Chagos Archipelago had been a dependency of initially French and then British colonial Mauritius. The U.S. Navy’s highest-ranking officer, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke, initiated secret conversations about the islands with his British counterparts, who were quickly receptive to the idea. By 1963, the proposal to create a base on Diego Garcia had gained support among powerful officials in the Kennedy administration, including the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Pentagon of Robert McNamara and Paul Nitze, Dean Rusk’s State Department, and the National Security Council (NSC) of McGeorge Bundy.

Prodded in particular by the NSC’s Robert Komer, the Kennedy administration persuaded the British—in contravention of international agreements forbidding the division of colonies during decolonization—to create a new colony by detaching the Chagos Archipelago from colonial Mauritius and additional islands from colonial Seychelles. They called it the British Indian Ocean Territory, and it was to be devoted solely to military use. In exchange for the detached islands, the British government agreed to build an international airport for the Seychelles, and in 1965 it paid £3 million to Mauritius. A British official described the compensation as “bribes” to ensure that both colonies would quietly acquiesce to the plan.7

A year later, the U.S. and British governments confirmed the arrangements with a little-noticed “Exchange of Notes.” This effectively constituted a treaty, but unlike a treaty, it required no congressional or parliamentary approval—allowing both governments to keep the plans hidden. Representatives of the two governments signed the agreement, as one of the State Department negotiators told me, “under the cover of darkness,” the day before New Year’s Eve 1966.

According to the Notes, the United States would gain use of the new colony “without charge.”8 In confidential agreements accompanying the Notes, however, the United States agreed to secretly transfer $14 million to Britain. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had approved the transfer of funds a year earlier, circumventing the congressional appropriations process.9

“A NEGLIGIBLE NATIVE POPULATION”

A fundamental part of Stuart Barber’s Strategic Island Concept was the idea of avoiding antibase protests. The Navy, Barber thought, needed to ensure it would have bases without “political complications” like those increasingly arising in the decolonizing world. Any targeted island would have to be “free of impingement on any significant indigenous population or economic interest,” Barber wrote. He was pleased to note that Diego Garcia’s population was “measured only in the hundreds.”10 The CIA’s assessment of the population size was even more telling: a report described it as “NEGL”—negligible.11 A Navy memo later concurred: “The selection of these islands was based on unquestioned UK sovereignty and a negligible native population.”12

Barber’s numbers were not entirely correct. There were around one thousand people in Diego Garcia alone in the 1960s. With the other Chagos islands, the population of the archipelago actually numbered between fifteen hundred and two thousand. The Chagossians had been living there since the time of the American Revolution, when they were brought to the previously uninhabited islands as enslaved Africans and indentured Indians to work on French coconut plantations. After slavery was abolished in the territory in 1835, this diverse group had developed into its own society, with a distinct culture and a language known as Chagos Kreol. They called themselves the Ilois—the Islanders.

But none of that mattered to U.S. officials. Navy Admiral Horacio Rivero approved the Diego Garcia acquisition plan and helped champion Barber’s idea to the Navy and the national security bureaucracy. According to Barber, Rivero insisted “emphatically” that the new base have “no dependents.”13 Other officials agreed. They wanted the Chagossians gone. Or as one document said, they wanted the islands “swept” and “sanitized.”14

Once British officials had agreed and base construction appeared imminent, any Chagossians who left Chagos after 1967 for medical treatment or a routine vacation in Mauritius were barred from returning home. Agents for the steamship company that connected the islands told the travelers that their islands had been sold and that they could never return. The Chagossians were marooned in Mauritius, separated from many of their family members and almost all their possessions.

British officials soon began restricting the flow of food and medical supplies to Chagos. As conditions deteriorated, more Chagossians began leaving the islands, hoping to return when the situation improved. Meanwhile, British and U.S. officials designed a public relations plan aimed, as a British bureaucrat wrote, at “maintaining the fiction” that Chagossians were migrant laborers rather than a people whose roots on Chagos stretched back across many generations. One British official called them “Tarzans” and, in a similarly racist reference, “Man Fridays.”15

By 1970, the U.S. Navy secured funding for what officials told Congress would be an “austere communications station.”16 Internally, though, Navy officials were already planning to ask Congress for additional funds to expand the facility into a much larger base. Construction on Diego Garcia began in 1971. In a memo of exactly three words, the Navy’s highest-ranking admiral, Elmo Zumwalt, confirmed the Chagossians’ fate: “Absolutely must go.”17

With the help of U.S. Navy Seabees, British agents began the deportation process by rounding up the islanders’ pet dogs. They gassed and burned them in sealed cargo sheds as Chagossians watched in horror. Then the authorities ordered the remaining Chagossians onto overcrowded cargo ships. During the deportations, which took place in stages until May 1973, most of the Chagossians slept in the ship’s hold atop guano—bird shit. Horses stayed on deck. By the end of the five-day journey, vomit, urine, and excrement were everywhere. At least one woman miscarried. Some compare conditions to those on slave ships.18

Upon arrival in Mauritius and the Seychelles, most Chagossians were literally left on the docks. They were homeless, jobless, and had little money. Most were able to bring only a single box of belongings and a sleeping mat. In 1975, two years after the last removals, the Washington Post exposed the story for the first time in the Western press. A reporter found the people living in “abject poverty,” victims of what the paper called an “act of mass kidnapping.”19

Aurélie Lisette Talate was one of the last to go. “I came to Mauritius with six children and my mother,” Aurélie told me. The family arrived in Mauritius in late 1972. “We got our house near the Bois Marchand cemetery, but the house didn’t have a door, didn’t have running water, didn’t have electricity,” she said. “The way we were treated wasn’t the kind of treatment that people need to be able to live. And then my children and I began to suffer. All my children started getting sick.”

Within two months of arriving in Mauritius, two of Aurélie’s children were dead. The second was buried in an unmarked grave because she lacked money for a burial. “We didn’t have any more money. The government buried him, and to this day, I don’t know where he’s buried.”

Aurélie herself experienced fainting spells and couldn’t eat. She had been “fat” in her homeland, she recounted, but in Mauritius she soon became alarmingly skinny. “We were living like animals,” Aurélie said. “Land? We had none.… Work? We had none. Our children weren’t going to school.” The Chagossians had lost almost everything, for no reason other than the happenstance of living on an island desired by the U.S. Navy.

THE BIKINI TESTS

The Navy’s expulsion of the Chagossians was not its first experience taking over tropical islands. After World War II, it had been given the responsibility of searching the planet for places to host the country’s first postwar nuclear weapons tests. “We just took out dozens of maps and started looking for remote sites,” explained Horacio Rivero, one of two officers charged with examining locations—the same Rivero who would later insist “no dependents” remain on Diego Garcia. “After checking the Atlantic, we moved to the West Coast and just kept looking.”20

Rivero knew something about islands. He was born in 1910 in Ponce, Puerto Rico, and during World War II he had served on the USS San Juan as it battled for islands across the Pacific, including Kwajalein, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. After the war, Commander Rivero moved to the Los Alamos nuclear weapons laboratory. There he worked for William “Deak” Parsons, who had helped drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima as a crew member on the Enola Gay.

In Rivero’s search for nuclear test sites, he considered more than a dozen potential locations around the world’s oceans. Officials ruled out most of them because the waters surrounding the islands were too shallow, the populations too large, or the weather undependable. Rivero even considered the Galápagos, but the Interior Department struck Darwin’s famed islands from the list. Eventually he settled on the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, then under U.S. control as a UN “trust territory.” The Navy was particularly pleased that Bikini had an indigenous population of only about 170 people.21

The Navy sent Commodore Ben H. Wyatt, known as “Battling Ben,” to “ask” the Bikinians for use of their islands. The answer was a foregone conclusion: President Harry Truman had already approved the removal, and preparations for a nuclear test on the islands had already begun. For their part, the Bikinians had been awed by the U.S. defeat of Japan and were grateful for the help the United States had provided since the war. They “believe[d] that they were powerless to resist the wishes of the United States,” according to Jonathan Weisgall, an attorney who has represented the group for decades.22

On March 7, 1946, less than one month after posing its question, the Navy completed the removal of the Bikinians to the Rongerik Atoll, elsewhere in the Marshall Islands. Within months it became clear that the move to Rongerik had been a disastrously planned mistake, leaving the Bikinians in dire conditions. The New York Times wrote in classically ethnocentric language that the Bikinians “will probably be repatriated if they insist on it, though the United States military authorities say they can’t see why they should want to: Bikini and Rongerik look as alike as two Idaho potatoes.”23

By 1948, the Bikinians on Rongerik were running out of food and suffering from malnutrition. After planning to move them to Ujelang Atoll, the Navy sent them to a temporary camp on Kwajalein Island, near a major U.S. base. Later that year, the Navy moved the islanders to a new permanent home on Kili Island. By 1952, as conditions again deteriorated, the government was forced to make an emergency food drop on Kili. Four years later, the United States paid the Bikinians $25,000—in one-dollar bills—and created a $3 million trust fund making annual payments. These totaled about $15 per person. “The Bikinians were completely self-sufficient before 1946,” explains Weisgall, “but after years of exile they virtually lost the will to provide for themselves.”24

Meanwhile, back on Bikini, the Navy conducted sixty-eight atomic and hydrogen bomb tests between 1946 and 1958. On March 1, 1954, the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test spread a cloud of radiation over 7,500 square miles of ocean, leaving Bikini Island “hopelessly contaminated” and covering the inhabitants of the Rongelap and Utirik Atolls. The Navy ultimately displaced people from six island groups in the Marshalls in addition to Bikini, including Ailinginae, Enewetak, Lib, Rongelap, and Wotho. In addition to deaths and disease directly linked to radiation exposure, the Navy’s evictions led to a veritable catalog of societal ills for the displaced, including declining social, cultural, physical, and economic conditions, high rates of suicide, poor infant health, and the proliferation of slum housing, among other debilitating effects.25

For his work in selecting Bikini for the nuclear tests, the Navy rewarded Horacio Rivero by making him an admiral—the first Latino admiral in Navy history. His next promotion made him the director of the Navy’s long-range planning office, where he would discover Stuart Barber’s “brilliant idea” for Diego Garcia.26

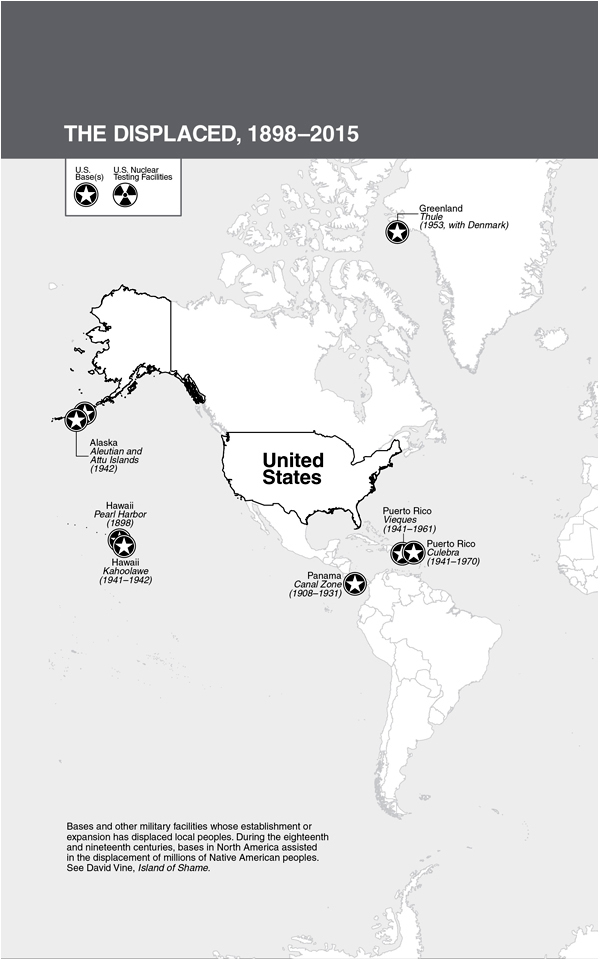

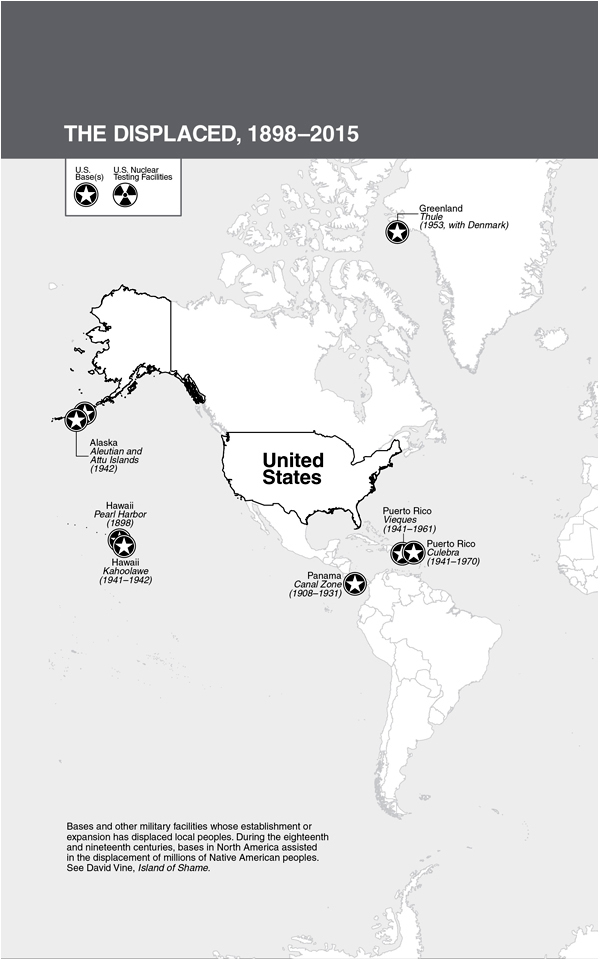

A CENTURY OF DISPLACEMENT

That the Navy would expel indigenous peoples from both Diego Garcia and Bikini is no coincidence. Around the world, often on islands and in other isolated locations, the U.S. military long displaced indigenous groups to create bases. In most cases the displaced populations have ended up deeply impoverished, like the Chagossians and Bikinians.

After a century of displacement in North America, there have been at least eighteen documented cases of base displacement outside the continental United States since the late 1800s. In Hawaii, for instance, the United States first took possession of Pearl Harbor in 1887, when officials coerced the indigenous monarchy into granting exclusive access to the protected bay. Half a century later, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy seized Kahoolawe, the smallest of Hawaii’s eight major islands, and ordered its inhabitants to leave. The Navy turned the island, which is home to some 544 archaeological sites and other sacred places for indigenous Hawaiians, into a weapons testing range. It wasn’t until 2003 that the Navy finally returned the island—now environmentally devastated—to the state.27

In Panama between 1908 and 1931 the United States carried out nineteen distinct land expropriations around the Panama Canal Zone, using the land to create not only the canal itself but also fourteen bases.28 In the Philippines, meanwhile, Clark Air Base and other U.S. bases were built on land previously occupied by the indigenous Aetas people. According to the anthropologist Katherine McCaffrey, “they ended up combing military trash to survive.”29

Some of the displacements began during World War II, ostensibly due to wartime necessity. However, most of those removed during wartime were prevented from returning at war’s end, and the initial evictions often paved the way for the displacement of yet more people in peacetime. Beginning in 1942, for instance, fearing a Japanese threat to Alaska, the Navy removed Aleutian islanders from their homelands. The Aleuts were forced to live in abandoned canneries and mines in southern Alaska for three years, even after Japan no longer posed a threat to the islands. In 1988, an act of Congress acknowledged that “the United States failed to provide reasonable care for the Aleuts, resulting in illness, disease, and death.” The act provided small amounts of compensation to some surviving Aleuts as well as to Alaska’s Attu islanders, who were prevented from returning to their homes after the war when the government built a Coast Guard station and later designated Attu Island a wilderness area.30

Similarly, after the U.S. military retook Guam from Japan in 1944, it displaced or prevented thousands from returning to their lands. As we will see, the military ultimately came to acquire around 60 percent of the island.31 In Okinawa, the military seized large tracts of land and bulldozed houses during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. Within a year, the United States had taken 40,000 acres and 20 percent of the island’s arable land. By the 1950s, the military had seized more than 40 percent of Okinawa’s farmland, ultimately displacing around 250,000 people, or nearly half the island’s population. A common refrain among Okinawans is that they lost their land by “bulldozer and bayonet.”32 A Navy officer would later say to the high-ranking Pentagon official Morton Halperin, “The military doesn’t have bases in Okinawa. The island itself is the base.”33

With the part of Okinawa left for civilians growing increasingly overcrowded, between 1954 and 1964 the United States induced at least 3,218 Okinawans to resettle 11,000 miles away, in landlocked Bolivia. (This was not entirely unheard of at a time when Japan arranged with several Latin American countries to accept its migrants.)34 The government promised them farmland and financial assistance. Instead, most found disease, jungle-covered lands, incomplete housing and roads, and none of the promised aid. By the late 1960s, the displaced Okinawans began heading to Brazil and Argentina and back to Okinawa and Japan.35

Closer to home, in Admiral Rivero’s homeland of Puerto Rico, the Navy carried out repeated removals on the small island of Vieques. Between 1941 and 1943, and again in 1947, the U.S. Navy displaced thousands from their lands, seizing three quarters of Vieques for military use, and squeezing the Viequeños into a small portion of the middle of the island. Military occupation brought few benefits. As productive local economies were disrupted, stagnation, poverty, unemployment, prostitution, and violence became the rule. In 1961, the Navy announced plans to seize the rest of Vieques and evict its remaining eight thousand inhabitants. Officials canceled the expulsion plans only when Governor Luis Muñoz Marin convinced President Kennedy that the expulsion would fuel UN and Soviet criticisms of the colonial relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico.

On Puerto Rico’s neighboring island Culebra, the Navy seized 1,700 acres in 1948 for a bombing range. By 1950, the island’s population, which had numbered four thousand at the turn of the century, had shrunk to just 580. The Navy controlled one third of the island and its entire coastline, encircling civilians with the bombing range and a mined harbor. In the 1950s, the Navy drafted plans to remove the rest of Culebra’s inhabitants. Although those plans were never executed, in 1970 it tried to remove the islanders again. When the issue became a cause célèbre for the Puerto Rican independence movement, the Navy stopped using the range. Bombing increased in Vieques as a result, until a campaign of civil disobedience stretching from Puerto Rico to New York City finally forced the Navy to leave Vieques in 2003.

In 1953, in a case echoing the Anglo-American expulsion of the Chagossians, U.S. officials signed a secret agreement with the Danish government to remove 150 indigenous Inughuit (Inuit) people standing in the way of expanding an American air base in Thule, Greenland. Inughuit families were reportedly given four days to move or face U.S. bulldozers. The Danes gave the Inughuit some blankets and tents and left them in exile in Qaanaaq, a bleak village 125 miles away.36 The expulsion severed the people’s connection to a homeland to which they, like the Chagossians, were intimately linked. The relocation led to the loss of ancient hunting, fishing, and gathering skills and caused significant physical and psychological harm. In recent years, Danish courts have ruled the Danish government’s actions illegal and a violation of the Inughuits’ human rights. Still, the Danish Supreme Court said they have no right to return.37

The displacement of indigenous groups for nuclear testing at Bikini also has its echoes elsewhere. Between the end of World War II and the 1960s, the U.S. military displaced hundreds of people to create a missile testing base in the Marshall Islands’ Kwajalein Atoll. Most were deported to the small island of Ebeye, where the population increased from twenty people before 1944 to several thousand by the 1960s living on 0.12 square miles of land. In 1967, with overcrowding a major problem, governing U.S. authorities removed fifteen hundred people from Ebeye.38 Following protests from the Marshallese government, they were later allowed to return. By 1969, Newsday called Ebeye “the most congested, unhealthful, and socially demoralized community in Micronesia.” A population of more than forty-five hundred lived in what has widely been called the “ghetto of the Pacific.”39 Today, there are around ten thousand people living on the island, making its population density greater than that of the world’s densest city, Mumbai.40

John Seiberling, a U.S. Congress member from Ohio, compared the conditions on Ebeye and military-occupied Kwajalein when he visited the islands in 1984:

The contrast couldn’t be greater or more dramatic. Kwajalein is like Fort Lauderdale or one of our Miami resort areas, with palm-lined beaches, swimming pools, a golf course, people bicycling everywhere, a first-class hospital and a good school; and Ebeye, on the other hand, is an island slum, over-populated, treeless filthy lagoon, littered beaches, a dilapidated hospital, and contaminated water supply.41

Seiberling’s description aptly captures not only the situation in the Marshall Islands, but the distance between the lives of troops at bases like Diego Garcia and the lives of Chagossians and other victims of displacement whose former lands the bases now occupy.

“NOBODY CARED VERY MUCH”

Former Pentagon official Gary Sick testified to Congress about the Chagossians’ expulsion in 1975, on the one day Congress has ever examined the issue. “The fact is,” Sick told me years later, “nobody cared very much about these populations.”

“It was more of a nineteenth-century decision—thought process—than a twentieth- or twenty-first-century thought process,” Sick said. “I think that was the bind they got caught in. That this was sort of colonial thinking after the fact, about what you could do.” And U.S. officials, Sick added, “were pleased to let the British do their dirty work for them.”

A former State Department official, James Noyes, who was involved in the creation of the base, told me that he and others considered the Chagossians a small “nitty gritty” detail that they thought the British were handling. “The ethical question of the workers and so on,” Noyes told me, “simply wasn’t in the spectrum. It wasn’t discussed. No one realized, I don’t think … the human aspects of it. Nobody was there or had been there, or was close enough to it, so. It was like questioning apple pie or something.”

In the minds of many U.S. officials, the supposed gains to be realized from a base justified what they saw as the limited impact of removing a small number of people. Henry Kissinger is widely reported as having said of the inhabitants of the Marshall Islands, “There are only ninety thousand people out there. Who gives a damn?”42 Stu Barber’s Strategic Island Concept was largely predicated on the same assumption: Who gives a damn? But from the perspective of the Chagossians and a long list of other peoples, there was of course nothing limited about the impact of their expulsion.

In her study of Vieques, Katherine McCaffrey notes that “bases are frequently established on the political margins of national territory, on lands occupied by ethnic or cultural minorities or otherwise disadvantaged populations.”43 While the military is generally driven by strategic considerations when deciding what regions should have bases, within a given region the selection of specific base locations is heavily influenced by the ease of land acquisition. The ease with which the military can acquire land tends to be strongly linked to the relative powerlessness of that land’s inhabitants, which in turn is usually linked to factors such as their nationality, skin color, and population size.

“Across history,” writes the former Air Force officer Mark Gillem, “displacements and demolitions are the norm.”44 Removing locals promises the ultimate in stability and freedom from what government officials generally consider “local problems.” U.S. officials displaced the Chagossians, the Bikinians, and others because the military prefers not to be bothered by local populations, and because it has the power to enforce its preference.

The displacement has not stopped. In 2006, in South Korea, the U.S. military wanted to expand Camp Humphreys, which already occupied two square miles, as part of the consolidation of U.S forces south of Seoul. At the behest of the military, the South Korean government used eminent domain to seize 2,851 acres of farmers’ land from Daechuri village and other areas near the city of Pyongtaek. When the farmers resisted, the government sent police and soldiers to enforce the evictions. Riot police went into Daechuri with bulldozers and backhoes, beating protesters, destroying a local school, and tearing up farmers’ rice fields and irrigation systems. When many still refused to leave, the government surrounded the village with police, soldiers, and barbed wire. In April 2007, the last villagers finally were forced to go. “I can’t stop shedding tears,” one older resident said. “My heart is totally broken.”45

The South Korean government has also seized a delicate and rare volcanic beachfront in the heart of a beautiful seaside village on its “Island of Peace,” Jeju. Despite years of passionate struggle by Gangjeong villagers and supporters, the government has dynamited much of the beach to build a Korean naval base. Given that the U.S. military has access to all South Korean bases and operational control over South Korean forces, many suspect that the new base is intended for U.S. forces.46

The displacement of Chagossians, Marshallese islanders, and other groups demonstrates the vulnerability of small, isolated populations whose forcible relocation U.S. officials have so often treated as a matter of negligible concern. The story of another group of islands underscores the decisive role that ideas about race have played in such decisions.47 Before World War II, Japan’s Bonin-Volcano (also known as Ogasawara) islands, which include Iwo Jima, had a population of roughly seven thousand. The islanders were the descendants of nineteenth-century settlers, most of whom had come from Japan but also from the United States and Europe. In 1944, Japanese officials evacuated all the Bonin-Volcano islanders to Japan’s main islands to protect them from impending U.S. attack. After the U.S. capture of the Bonin-Volcanos, American officials prohibited the locals from returning in order to give the military unhindered use of the islands. In 1946, however, officials modified the decision: they would “permit the return of those residents of Caucasian extraction who had been forcibly removed to Japan during the war and who had petitioned the United States to return.”48

U.S. authorities subsequently assisted with the repatriation of approximately 130 Euro-American men and their families to the Bonin-Volcano islands. The Navy helped them establish self-government, allowed children to attend a Navy school, and created a cooperative trading company to market agricultural products on Guam and a Bonin-Volcano Trust Fund to provide financial support.49 The only differences between this community and the Chagossians were the color of their skin and their ties to the United States.

STRUGGLE AND SAGREN

After years of protest, including a series of five hunger strikes led by women like Aurélie Talate, Chagossians finally received small amounts of compensation from the British government, ten and fifteen years after the last expulsions. The compensation consisted of small concrete block houses and small plots of land for some of the Chagossians, and money totaling less than $6,000 per adult. Others, including all those living in the Seychelles, received nothing.50 Many of those who did receive compensation used the money to pay off large debts accrued since the expulsion. For most, conditions improved only marginally.

Numbering more than five thousand today, most Chagossians remain impoverished. They are still struggling to win proper compensation and the right of return. In 2002 they secured the right to full UK citizenship, and since that time well over one thousand Chagossians have moved to Britain in search of better lives. Even the ones who have found housing and employment there, though, are often stuck working long hours in low-wage service sector jobs.51

Aurélie Talate had no interest in moving anywhere except back to her home on Diego Garcia. Unfortunately, she will not see the day when Chagossians return to their homeland. She died in 2012 at the age of seventy, succumbing to what Chagossians call sagren—profound sorrow.

“I had something that had been affecting me for a long time, since we were uprooted,” Aurélie told me a few years before her death. “This sagren, this shock. It was this same problem that killed my child,” she said. “We weren’t living free like we did in our natal land. We had sagren when we couldn’t return.”

Stu Barber also will not see the Chagossians return. Before his death, however, Barber discussed the prospects of a return in a 1991 letter to the Washington Post. “It seems to me to be a good time to review whether we should now take steps to redress the inexcusably inhuman wrongs inflicted by the British at our insistence on the former inhabitants of Diego Garcia and other Chagos group islands,” Barber wrote.

There was never any good reason for evicting residents from the Northern Chagos, 100 miles or more from Diego Garcia. Probably the natives could even have been safely allowed to remain on the east side of Diego Garcia atoll … Such permission, for those who still want to return, together with resettlement assistance, would go a long way to reduce our deserved opprobrium. Substantial additional compensation for 18–25 past years of misery for all evictees is certainly in order. Even if that were to cost $100,000 per family, we would be talking of a maximum of $40–50 million, modest compared with our base investment there.52

Barber’s letter went unpublished and he received no reply from the Post. Similar letters imploring a former Navy supervisor and the British embassy in Washington to help return the Chagossians to Chagos also received no answer.

In yet another letter, to former Alaska senator Ted Stevens, Barber confessed, the expulsion of the Chagossians “wasn’t necessary militarily.”53

A lusong (mortar) among the archaeological remains at Pågat, the ancient indigenous village and sacred burial ground on Guam where the U.S. Marine Corps proposed building a shooting range.