Case Study 9A

School Climate: The Road Map to Student Achievement

Vanessa A. Camilleri

Background

Inner city schools are often faced with the challenge of educating children who, due to the cumulative effects of violence, abuse, and poverty, come to school unprepared to learn. Faced with daily environmental and domestic stressors, many children enter our school buildings angry, hungry, scared, tired, or lonely. These stressors often manifest as academic failure, aggression, or depression, which hinder success in school. Often, before teaching to the standards, educators must tend to children who don’t share, who solve their problems with fists, who are bullied and isolated, and who survive with little guidance. For many children, school is their only safe haven, and if it’s not, the school has failed.

A safe school is one with a positive school climate in which positive relationships, communication, and expectations along with equitable teaching, leadership, and organizational practices are the glue that holds the community together. These conditions are necessary for students to feel free to speak up, make mistakes, take risks, venture an opinion, or ask a question. A school with a positive school climate provides the foundation to ensure that students are socially, emotionally, and behaviorally ready to receive instruction and to thrive.

The Arts and Technology Academy (ATA) is an elementary charter school located in an urban Washington, D.C., neighborhood serving 590 predominantly low-achieving students from the local community. Of these students, 99 percent are African American, and 92 percent qualify for free or reduced-cost lunch. I joined the staff as a music therapist in 2001 with my main responsibility being to provide social skills groups for regular-education children exhibiting disruptive behaviors. Each year I would observe children for the first month of school and then meet with each teacher to narrow down the list of referrals for music therapy. I carried a case load of approximately seventy-five students every quarter and always had a waiting list. After four years of leading a successful program, a turning point came when one teacher stated during her referral meeting, “My whole class needs anger management!” This was the clarifying moment: social skills interventions were impacting individual students and the school leadership was 100 percent supportive, but the overall climate of the school was not supporting these efforts.

The year was 2005. ATA was struggling to make adequate yearly progress, and there was a climate of disrespect overall, including top-down decision making, poor staff and student attendance, severe behavior management concerns, low staff morale, and high teacher turnover. In addition, troubling neighborhood trends coupled with rising incidents of violence in schools nationwide and an emphasis on national testing were combining to make the conditions for individual student success at ATA nearly insurmountable.

Thanks to a turnover in school leadership, I was able to convince the new administration that I could better serve the school and would definitely reach more children by working at the administrative level by being responsible for proactive schoolwide structures and programs to address school climate and the social and emotional well-being of our staff and students. My role on the leadership team was as the social-emotional learning specialist, working directly with the staff to research and implement processes that began to impact our building.

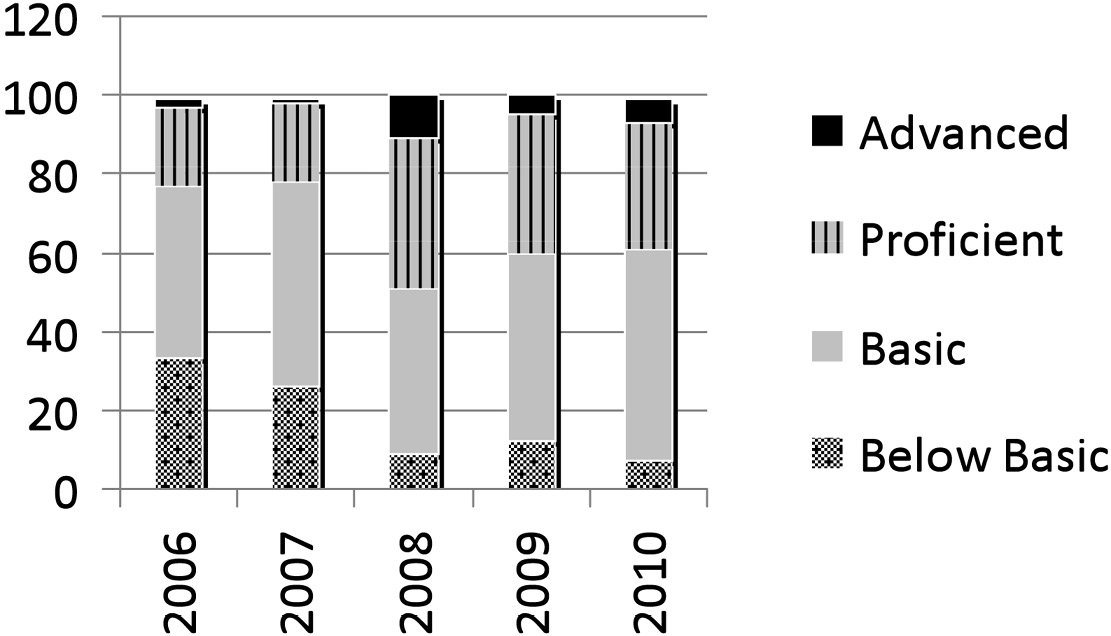

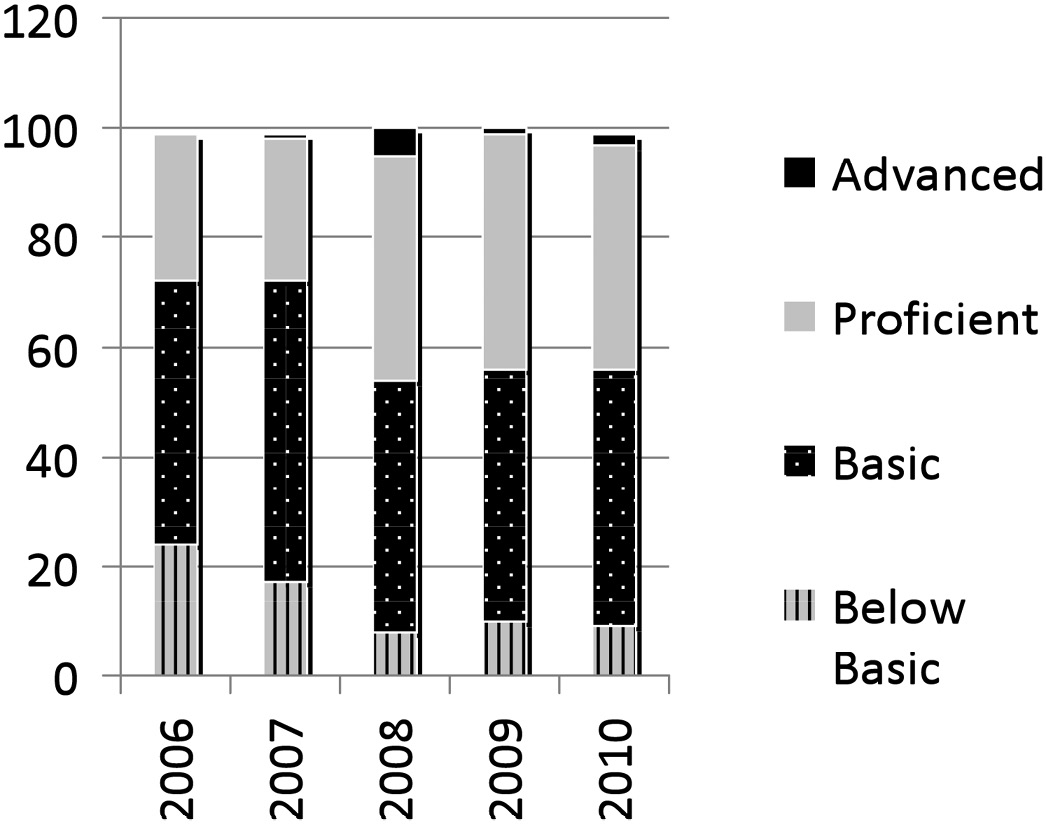

We have seen improvements in teacher quality, staff morale, student and staff attendance, and student achievement scores as well as reduced teacher turnover, behavior referrals, and suspensions. From 2006 to 2009, our reading scores went from 20 percent of our students scoring proficient to 40 percent scoring proficient, and our math scores went from 27 percent scoring proficient to 44 percent scoring proficient. In addition, over the same time span, we saw a 40 percent reduction in behavior referrals. Students and staff alike have become motivated, inspired, and focused on social and academic achievement and have become advocates for school climate change.

Rationale

A positive school climate develops with contributions from all stakeholders: students; teachers; parents; support staff (cafeteria, security, maintenance); administrators; consultants; and volunteers. This responsibility holds true in every location or gathering in which ATA community members are present (in and out of the building): classrooms, hallways, cafeteria, auditorium, playground, clubs, sporting events, field trips, arts/resource classes, staff lounge, staff meetings, parent–teacher conferences, and board meetings. We understand that teaching and learning happens most effectively within the context of a positive school climate and in classroom communities that are physically and emotionally safe, positive, orderly, fair, and compassionate. Developing a positive school climate enables us to provide this optimal teaching and learning environment where professional, academic, social, and emotional needs can be met.

ATA has committed to making a positive school climate purposeful rather than accidental and to be explicit about the “hidden curriculum” (Jerald, 2006). We have decided to define our own school climate rather than letting a negative subculture define us. We have refused to fall back on excuses for failure and instead chose to acknowledge and address nonacademic barriers to achievement in a systematic and innovative manner. To that end, since 2005 our school has undergone a comprehensive school climate change process that has closely followed the five stages of the National School Climate Council’s school climate improvement model (described in chapter 9). Here’s how ATA met the challenges of the five stages.

Stage 1: Preparation

Identifying a lead administrator to be responsible for “school climate improvement” indicated a programmatic and financial commitment from the leadership to support this initiative. Once my role and funding needs were clarified, I was able to introduce the concept of school climate during an administrative retreat during the summer of 2006. I shared the importance of balancing academic and social learning and that one would enhance the other through a number of processes. I introduced the Responsive Classroom approach to teaching and learning (Northeast Foundation for Children) which would be implemented at school as a way to provide concrete practices for our staff (Morning Meeting, Hopes and Dreams, Rule Creation, Guided Discovery, Academic Choice, and Positive Language), as well as a theoretical foundation for our practice. During the retreat, the leadership team selected four major school initiatives for the coming year. School climate was one of them. Next I began planning summer training for the full staff.

Key to this initial step was ensuring that we capitalized on what was already in place in our building and introduced school climate to the staff not as something brand new, but as something that already existed in our building that needed more focus. We did this in three major ways, as follows:

|

1. |

Classroom community plan. We modified a document originally called the “classroom discipline and responsibility plan,” which required teachers to lay out all rewards and punishments they would use to manage their classroom. We changed the name to the “classroom community plan” and required teachers to identify ways in which they would proactively manage their classrooms through |

|

|

a. |

building community, |

|

|

b. |

building relationships, and |

|

|

c. |

maintaining clear expectations. |

|

|

These three threads run through all areas of our school, allowing us to provide and coordinate a systematic approach to behavior management. |

||

|

2. |

Pride motto. We revisited our core values (perseverance, respect, integrity, discipline, and enthusiasm) in order to make them become living and breathing pillars in our school rather than words that lived on a poster in every classroom. These values would become central to our future action planning. |

|

|

3. |

Report cards. We changed the “work habits” section on the report card, which included items such as “completes class work on time” and “complies with school rules,” to the “social emotional learning skills” section, which now includes |

|

|

a. |

“Demonstrates self-control in managing emotions and behaviors”; |

|

|

b. |

“Is kind and caring toward others”; |

|

|

c. |

“Interacts effectively with others”; |

|

|

d. |

“Prevents, manages, and resolves conflicts in positive ways”; and |

|

|

e. |

“Contributes to the well-being of the class, school, and community.” |

|

To help with adequate assessment of these skills, we developed social-emotional learning assessment rubrics for each grade level that assess students on specific benchmarks for each of the social emotional skills. This rubric is kept in student portfolios and can be used by teachers during parent–teacher conferences or special education meetings.

Workshops during summer training included the theory behind school climate (we used information from the National School Climate Center) and social-emotional learning (information from the Collaborative for Social, Emotional. and Academic Learning) as well as concrete information about implementing these concepts in our building. Any school climate change clearly requires a parallel process to occur between the adults and children in the building. For the first time in my years at the school, we began every day of training with a team-building activity led by a different staff member. This action set the tone for the school year and built positive relationships between the staff. The culminating team-building activity was creating the staff mural to which everyone contributed. During the entire two weeks of training, a craft table was set up for staff to decorate quilt pieces for the patchwork of educators. Staff members decorated individual pieces of the quilt with photos and words that provided personal descriptions of themselves. The staff mural remained in the lobby the entire year. We now create a new mural every year that focuses on a particular theme such as “My hopes and dreams for the year are . . . ,” “I inspire children by . . . ,” and “My essential contribution to ATA is . . .”

Stage 2: Evaluation

Moving through the first year, a few key staff members began to show an interest in learning more about school climate and helping to further develop the initiative. In response, a social-emotional learning (SEL) committee began on a volunteer basis and serves to assess progress and action plans and make programming and implementation recommendations.

The SEL committee selected the Comprehensive School Climate Inventory (CSCI; described in chapter 9) to administer to staff and third- through sixth-grade students every year to assess progress on ten school climate dimensions. This survey became the foundation of our action-planning process, pointing to gaps and areas that required further research (through focus groups). Assessment of the school climate initiative is an ongoing process that requires an ability to analyze and use primary and secondary data sources in order to make real, on-the-ground changes. By including staff in school climate data analysis and study, the SEL committee’s critical role over the years has created buy-in and momentum. Our staff has seen firsthand that focusing on the climate in our building has not only improved the learning environment for students, but has also improved the professional environment for our staff.

Stage 3: Understanding and Action Planning

Having a committee focused on school climate development is extremely helpful when you begin to try to make sense of school climate data. At the end of the first year, we focused on determining which area of school climate was viewed most negatively by the school community. The CSCI does a great job of ranking ten dimensions of school climate, which allows us to make educated decisions based on reports by staff and students. These rankings led to many discussions about prioritizing efforts, since the worst-ranked dimension may have been ranked low due to failure in another area. For example, to better understand a low rating in the perceived social-emotional security dimension, it may be useful to look at the ratings for the dimensions on perceived adequacy of social supports. Deciding where to start was difficult, but we knew we had to begin with a narrow entry point. Our first target area was “respect” because it was viewed as the most negative by staff and students. Through reviewing definitions for respect, we examined each question on the inventory that addressed respect and came up with four general action areas capable of positively impacting respect in the building:

- cultural exposure,

- parental engagement,

- staff community building, and

- building student self-esteem.

Committee members then signed up to work on the plan and led individual SEL projects, which addressed the four action areas during the school year.

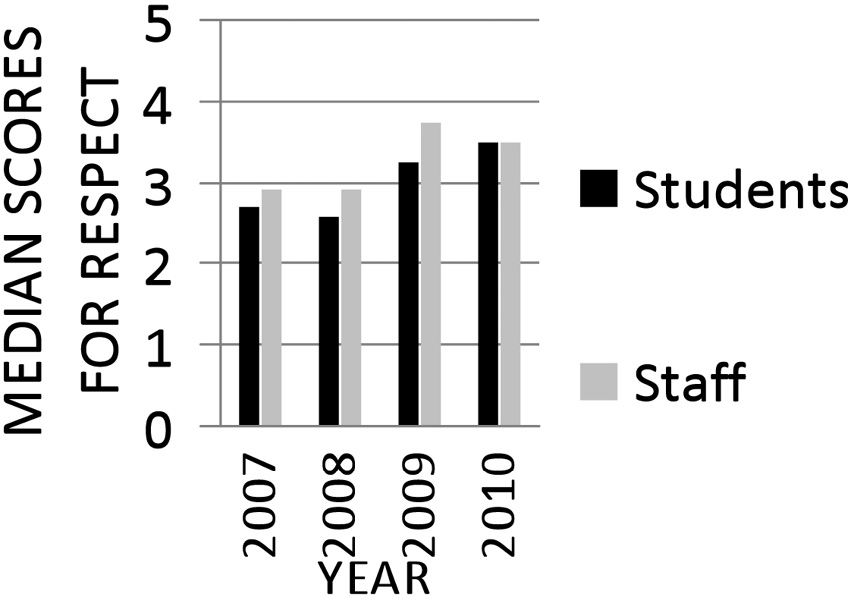

Stage 4: Implementation

Following the above process, we have implemented multiple SEL projects that have improved respect in our building, including a positive language campaign, an antibullying campaign, peer mediation, cross-age peer mentoring, pen pals with a school in England, a family scavenger hunt around the city, a summer postcard drive, a wall of pride, speak-out boards, Respecting Our Community awards (ROC STARS), community morning meetings, and much more. As you can see from the results illustrated in figure 9A.1, scores for respect have risen steadily over the past four years.

Figure 9A.1. Change in median scores for respect.

Stage 5: Reevaluation

As we have continued our cycle of school climate data analysis and action planning, we have additionally examined secondary sources of school data (e.g., attendance, test scores, attrition, retention, behavior referrals, parental involvement) to see whether our school climate initiative can be linked to progress in other areas of the school. We are pleased to report that our behavior referrals have dropped by 42 percent over the past four years and our test scores have continued to rise as seen in figures 9A.2 and 9A.3, allowing us to make AYP for two out of the last four years through the Safe Harbor provisions of the No Child Left Behind Act.

Figure 9A.2. Performance in math.

Figure 9A.3. Performance in reading.

We have also supplemented our planning by conducting site visits to other schools to identify best practices, developing relationships with other schools heading up similar efforts, attending and presenting at conferences, and referring to current research.

Recent school climate data analysis at our school has revealed that while staff and student data for respect continue to rise, results show that scores for “social-emotional safety” have steadily been decreasing over the past four years. This finding was a surprise because our school appears and feels safe. There are very few outright fights. However, thanks to focus groups and discussions with staff, we have identified much “soft bullying” going on below the radar of the adults in the building. This bullying includes gossip, rumors, teasing, name-calling, and more and is taking place in hallways, bathrooms, and on the playground. This knowledge led to a major schoolwide antibullying campaign this year, which would not have been launched without in-depth analysis of school climate data.

Practical Foundations

A number of practical approaches have allowed us to develop a coordinated and comprehensive school climate change effort at ATA. The following components have developed over time but should be considered at the onset of any initiative.

|

1. |

Professional development of school climate |

|

|

a. |

Instructional approaches that promote positive school climate development. |

|

|

b. |

Proactive behavior management that sets the tone in the classroom. |

|

|

2. |

Action planning |

|

|

a. |

Developing a committee that includes people from different areas of the schools. |

|

|

b. |

Making programming decisions that are aligned with school climate efforts, including school climate elements in all strategic planning efforts and school improvement planning. |

|

|

3. |

Accountability |

|

|

a. |

Data collection on school climate dimensions. |

|

|

b. |

SEL standards on student report cards. |

|

|

c. |

School climate practices included on teacher evaluation. |

|

|

d. |

School climate practices included in hiring and firing decisions. |

|

|

4. |

Operations |

|

|

a. |

Hiring dedicated personnel to be responsible for school climate development. |

|

|

b. |

Ensuring that there is dedicated funding to support school climate development efforts. |

|

|

c. |

Considering school climate when making all scheduling decisions. |

|

Outcomes

The school climate change effort truly has become a schoolwide initiative. We now understand that our building’s climate is the glue that holds all other initiatives together. On the flip side, it can be the instrument that makes it all fall apart.

Contributing to our positive school climate is nonnegotiable in our building, and all staff and students are held accountable for their efforts. We have seen our school become a more positive place to work and our classrooms become more positive places to study. Through coordinated efforts around areas such as positive language, proactive behavior management, instruction that infuses social competency development as well as content knowledge, and equitable management approaches, our efforts to develop a more positive school community have paid off. Testaments to the kind of school ATA has become include improved test scores and attendance rates, and reduced behavior referrals and student/staff absences. These results did not happen accidentally but purposefully and based on data-driven action planning.

Pushback

Like most change in schools, staff will have varied responses and levels of buy-in that range from resistance to compliance and whole-hearted adoption and intellectual and behavioral change. The main problem with school climate change is creating consistency of beliefs, expectations, and practice. Since mandated standards for school climate do not exist, healthy debates within states, districts, and school buildings can contribute to the definition of “positive school climate.” If the end goal is not clearly articulated or supported by all key stakeholders, then the road to getting there will be bumpy and slow.

The issues of time and accountability are important. Common pushback can include “I don’t have time to get to know my students,” “I don’t have time to do team-building activities,” “Are the students being tested on their cooperation skills?,” and “Am I being evaluated on how well I build community in my classroom?” Schools must decide how to tackle these very real teacher concerns. I believe a full commitment from the school must include accountability measures as well as required training on building a positive school climate for improved student outcomes. Done well, positive school climate development will not take extra time but will be aligned with and infused into what is already happening during the school day. Positive school climate must be on the radar all day, every day. For example, we would not advise “teaching” positive language for thirty minutes twice a week, but rather it should be taught, practiced, and modeled daily during instruction and all interactions with all adults in the building.

Lessons Learned

To summarize our experience, school climate change

- takes time;

- is a work in progress;

- cannot be forced;

- must be based on what is already in place;

- must be goal driven;

- must be data driven;

- must be research driven;

- must include everyone in the building;

- should work toward shared definitions and goals;

- should work toward buy-in, capacity building, and sustainability; and

- must be comprehensive, systematic, and purposeful.

Next Steps for ATA

The cycle of school climate improvement continues nonstop, especially as we welcome new students and staff to the school yearly. We continue to refine our commonly held beliefs about the type of school we are striving to achieve, and to involve all stakeholders in this process in an effort to build capacity throughout our organization.

As we continue to develop sustainable practical approaches, we base our actions on current theory and research, and we look for best practices and resources to guide our efforts. This process will help us to deepen the inroads made to impact school climate and broaden the different avenues to get there, for example, aligning instructional methods, management approaches, parental involvement, and community partnerships. Most importantly, we continue to aspire to serve as a model for other schools. We are committed to learning from our successes and failures in an effort to become leaders in the field and advocates for school climate reform efforts at the national level.

Reference

Jerald, C. D. (2006). School culture: “The hidden curriculum.” Center for Comprehensive School Reform and Improvement, issue brief, number 6. Retrieved from www.centerforcsri.org