Chapter 17

Building a Prosocial Mind-Setin Teacher and Administrator Preparation Programs

Jacqueline Norris and Colette Gosselin

On the way home from teaching class one night, the following story recounted by a young middle school boy was broadcast on a radio program. I would like to share the story and the seemingly unintentional lesson learned by others because of this young student, whom we will call Jason. Jason’s middle school class was on a field trip to visit the New Orleans Museum of Art. He and his peers were very excited about visiting the museum and viewing all the wonderful art that would be on exhibit inside. There had been much class preparation about the artists and the kinds of artwork that would be on exhibit. There had been lessons about art of every imaginable kind to prepare the students so that they would truly benefit from this experience and from all the effort their teacher had invested in their study about art and artists.

As Jason, his classmates, and the teacher were about to enter the museum, the class passed a homeless man on the street holding a sign that said, “Do you have food to spare?” He and his classmates walked by the homeless man, entered the museum, and set out to enjoy the experience they had been anticipating. After the museum tour, the children exited the building to enjoy an outside picnic. Remembering the homeless man, Jason looked around to see if he was still there. And indeed he was. Upon seeing him, Jason asked his teacher if he could share part of his lunch with the man. The teacher said yes and accompanied him over to the man. Seeing what Jason had done, his classmates collected enough food from their lunches to feed four other men who were nearby.

As I drove home, I could not get that story out of my head. I kept thinking, what beliefs must Jason have had to want to help as he did? What beliefs motivated the teacher to say yes, and the other students to join in? Were their beliefs nurtured in the family? Did the school support and strengthen them? These were surely prosocial behaviors—that is, the desire to help and care for others without the expectation of a reward. The behaviors were seen, but what motivating beliefs led to the acts? I thought, these are the kinds of behaviors that make a difference in our world. As a school leader educator, these are the kinds of beliefs and behaviors I intend to foster in my students and for them to use to develop schools as places where everyone in the community feels safe, affirmed, and valued.

Sharing this story and my thoughts with my colleague and coauthor, she too had the same intention for her preservice teachers. We both expect our students to be educators of the heart as well as the mind and to realize that schools are social settings that reflect and shape our society at the same time. We talked about the challenges we place before our students to examine their belief and value structures and how these structures shape the behaviors we want them to demonstrate. As they move into their future roles as school leaders and teachers, we want them to act purposefully and intentionally as agents of change and advocates for others. This chapter is a discussion of the prosocial approach and theoretical framework we use in two of our respective classes to help our students examine and strengthen the beliefs and competencies which lead to the kinds of behaviors demonstrated by the young student, his classmates, and the teacher in the story above.

Our Approach to Developing Prosocial Behavior

Prosocial behavior is “other oriented.” Eisenberg and Mussen define prosocial behavior as “voluntary actions that are intended to help or benefit another individual or group of individuals” (1989, p. 3). Furthermore, they explain that these acts are intrinsically motivated; that is, they are “acts motivated by internal motives such as concern and sympathy for others or by values and self rewards [such as feelings of self-esteem, pride, or self-satisfaction] rather than personal gain” (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989, p. 3). The term prosocial is an umbrella term that incorporates such fields as character education, moral education, social and emotional learning, civic education, and school culture/climate. Though these approaches vary in their perspective, they all address human beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that lead to a more caring, respectful, and responsible individual.

Our approach to developing prosocial behaviors in our students is grounded in the theories of social and emotional intelligence. In his seminal work on emotional intelligence, Daniel Goleman (1995) identified what he terms the hallmarks of character and self-discipline, of altruism and compassion—the basic capacities needed if our society is to thrive (Goleman, 1995). Goleman further describes four areas that comprise social and emotional intelligence: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. Each is briefly described below.

Self-awareness is the ability to recognize one’s feelings while they are being felt.

Self-management is the ability to act constructively on those feelings in appropriate ways.

Social awareness is the ability to recognize the feelings of others without judgment and interact in ways that demonstrate caring and concern for others.

Relationship management is the ability to interact effectively with others by building trust, honesty, and caring. In fact, the ability to manage one’s relationships well requires all three areas listed above.

By definition, both social awareness and relationship management specifically target one’s interactions with others; the connection between these two categories and prosocial behavior is relatively clear. But at first glance the connection between self-awareness and self-management and prosocial behavior may be less obvious. As we understand it, in order for a person to even possess the capacity to respond to others, that person must first be aware of feelings that are stirred in the actual moment of the interaction, be able to manage those feelings as they are stirred, and, finally, be able to evaluate those feelings to determine their appropriateness to the situation at hand. This process must occur quickly in order for the appropriate response to occur. In addition, we want to point out that while self-awareness and self-management may not be observable qualities, we contend that it is in the result that these capacities become evident and make responsiveness possible. For these reasons, we include both self-awareness and self-management as not only essential qualities but also foundational competencies for future educators.

Let’s return for a moment to Jason’s story. On that day outside the museum, many individuals must have passed by the homeless man. Some may have had an initial stirring of some feeling, and certainly Jason was one of those individuals. But unlike others, Jason’s stirring caused him not only to feel “something” but also to know what this “something” was—empathy. Awareness of his feelings over time (recall that considerable time passed between Jason initially setting eyes on the homeless man and exiting the museum with his classmates) led Jason to action. In addition, Jason must also have felt a deep sense of trust in his teacher that enabled him to approach the teacher with a request to share his lunch. In turn, the teacher, in a show of caring and support for Jason, accompanied him as he walked over to the homeless man. To protect the student, a different teacher might have discouraged Jason. Instead, this teacher not only demonstrated compassion for the homeless man but also showed caring, respect, and concern for the relationship he had built with Jason. As a result, he actively encouraged Jason’s prosocial actions and subsequently might have taught the most significant yet unplanned lesson of that museum field trip! As educators of future leaders and teachers, it is this type of learning rooted in care, respect, and concern for others that we intend to instill in our own students. Our hope is that by fostering this mind-set in our own classrooms, our students will in turn build schools and classroom communities that continue the cycle of prosocial behavior.

Table 17.1 provides questions drawn from Smart School Leaders: Leading with Emotional Intelligence (Patti & Tobin, 2006). These questions can help frame our thinking as we, teachers and leaders, self-assess and make decisions about ways we can improve in each of Goleman’s four areas. Later in this chapter, we will show which of and how these questions are embedded in our course content, activities, assignments, and assessments.

Table 17.1. Questions Drawn from Smart School Leaders: Leading with Emotional Intelligence (Patti & Tobin 2006)

|

Self-awareness How well am I aware of my own feelings? Do I recognize my own body cues and emotional triggers? Do I see how my emotions affect my performance? Can I laugh at my mistakes and learn from them? Do I have presence? Do I believe that I am good at what I do? Can I hear you when you give me positive and negative feedback? |

Social awareness Can I see, hear, and observe the perspectives of others? Am I sensitive to the differences in others? Can I listen without judgment? How well do I know the political current of my classroom/school? Can I see and understand power relationships and utilize them positively? Do I really understand and influence the culture in which I work? Do I know what people need to thrive? Am I available to them when needed? |

|

Self-management Can I remain calm under stress? Can I control my impulses? Do my actions reflect my beliefs? Am I an ethical person? Do I follow through on commitments? Can I smoothly handle all demands on me? Can I change my plan midstream even if I believe I am right? Can I make a difficult situation positive? Do I take calculated risks? Do I set measurable goals for others and myself? Can I get out of the box and embrace new challenges regularly? |

Relationship management Do I mentor and coach others effectively? Do I give constructive feedback to others? Do I see the strengths of others? Do others view my vision as valuable? Can I motivate others? Do I engage others verbally and nonverbally? Can I energize and guide others to make a needed change? Do I really know how to manage conflict positively? Am I gifted at nurturing relationships and building community? Can I work well in a team and help others to do the same? |

Our Organizing Framework

In higher education, we are perpetually searching for the best means to prepare future teachers and leaders. In a seminal essay that suggests a holistic approach for teacher preparation, Fred Korthagen (2004) raises two central questions for teacher educators: “What are the essential qualities of a good teacher?” And, should we be able to identify those qualities, “How can we help people to become good teachers?” As educators in two different programs, one in educational leadership and the other in teacher preparation, we have found that Korthagen’s two questions sit at the core of our programmatic goals. Further, we have also extended these two questions to more deeply examine a companion set of questions in the two courses we will describe in this chapter: “What essential qualities do school leaders and teachers need to promote a prosocial environment in classrooms and schools?” and “How do we help them develop those qualities in the settings in which they will work?” Before beginning to describe the courses we teach and how we set out to build a prosocial mind-set in preservice educators, we wish to first describe Korthagen’s “onion model,” which aptly describes the dynamic process of identity development that educators undergo and then connect Korthagen’s model of change to our prosocial goals.

Korthagen’s Onion Model

As Korthagen (2004) explains, much of the literature over the past decades in teacher preparation has focused on describing a good teacher based on two prominent themes: (1) competencies teachers should develop and (2) personal attributes that a teacher needs to develop to be effective. Much of the competency literature approach in teacher preparation stems from the middle of the twentieth century, when “performance-based” or “competency-based” models for teacher preparation gained ground. The beliefs of this approach are rooted in the idea that if we successfully generate a concrete list of the competencies a teacher needs to have, then we could use this list to train teachers. Korthagen correctly points out that one consequence of this belief has been efforts to correlate teacher competencies with student achievement. In fact, current reform efforts such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB) stem from this approach to teacher preparation. Less significant criticisms of this approach cite the unwieldy nature of the list this approach would generate and the problems it would pose should we act on competencies that are decontextualized from the settings in which they were identified. The second prominent approach that Korthagen identifies concerns beliefs about teacher personality traits, a trend rooted in the humanistic-based teacher education model, which focuses mainly on teachers’ personal characteristics such as enthusiasm, nurturing ability, and love of children.

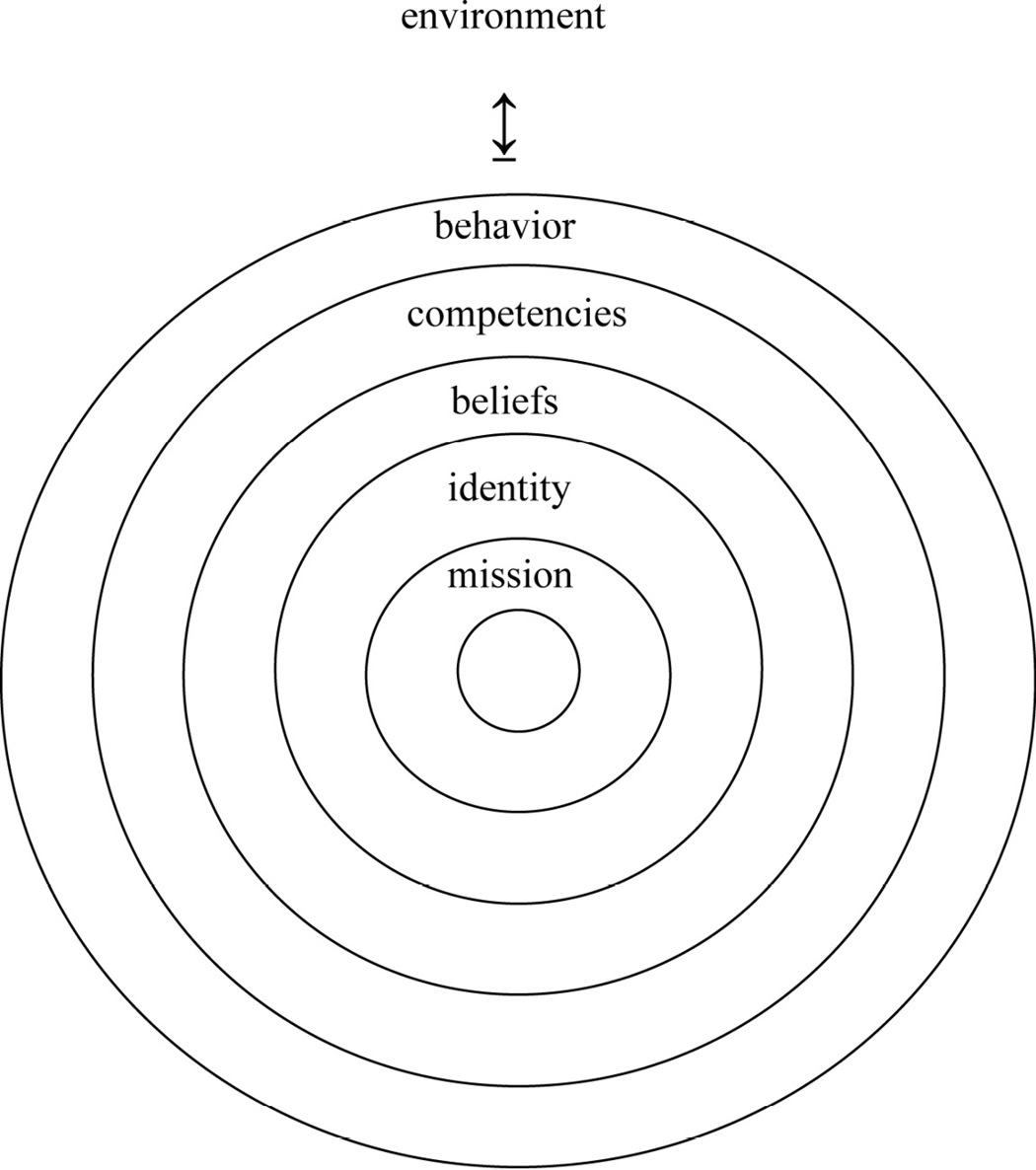

Korthagen (2004) critiques these two approaches to teacher preparation and in their place offers a holistic, dynamic model that takes both competencies and educator beliefs, not personality, into account. Briefly, his model consists of a nested set of five layers that act in concert and therefore influence each other (see figure 17.1). We find that this model provides an excellent framework to explain the goals of our two courses and our intentions of preparing educators with a mind-set that fosters the development of the requisite awareness and perspectivity needed to be prosocial, empathic actors.

External to the five concentric layers of the onion is the environment or the context in which an individual is an actor. Since the environment is where our social interactions occur, it also serves as the place that affords us continuous experiences from which we learn to think, respond, and act. If we imagine the environment as an infinite number of onion bubbles, then we can begin to visualize ourselves and our own “onions” bumping into and bouncing off of an endless stream of other onions. This bumping into and bouncing off of constitutes our social life. As Korthagen (2004) explains, this bumping and bouncing is bidirectional and has a ripple effect on both the inner layers and the environment in which the onions interact. In fact, in the process of change, a bidirectional relationship or interplay exists between all concentric layers. Too, the environment can change as a result of its interaction with the outer layer of the onion bubbles.

As we review the model, we will begin by discussing the outermost layer, our behaviors. This part of our onion is the only observable layer and represents that part of ourselves that we share in our encounters within the social world as we interact with others. The significance of this layer lies in the fact that we are only privy to what we observe in other people’s behaviors, and we are inclined to make decisions based on those observations. Yet these observations may not be factual and in fact tend to be laden with assumptions and misconceptions generated by previous encounters from which we have constructed meanings and labels. As Korthagen (2004) explains, we neglect the inner layers as they are simply not observable to us. If we return to the story about Jason, all that we can truly know about this story are the facts—a young boy shared his lunch with a homeless man, and his classmates followed his example. So, how then does Korthagen’s model help us understand more about prosocial behavior? His model clarifies the unseen.

Below the layer of behaviors is the layer of competencies. Korthagen (2004) defines competencies as an integrated body of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that represent the potential for behavior. This list is almost inexhaustible, so perhaps more important than the list itself is the fact that conditions in the environment will largely determine whether or not a competency is put into practice should it already exist. Also important is that a new condition may stir the desire to learn a new competency if it does not already exist. Let’s look at two different examples of how this might work. The first example involves a principal who implements a disciplinary policy with the intention of lessening disruptive behavior because he or she believes that the students require a strong external control system. This system may work well for some students but not for others who the principal notes seem to be repeatedly assigned detentions and suspensions. At this point, an effective principal will reflect on his or her decision-making process. We encourage our students to consider the possibility that the repeat offenders may require something more than those for whom the policy seems to be most effective; we suggest that they may need to rethink their beliefs about what is motivating the repeat offenders. In fact, this rethinking may lead an effective principal to not only consider new methods for disciplinary actions, but to also recognize the need for new instructional approaches and curricula that target the interests of that student population. Next, an effective principal might evaluate his or her teachers’ competencies and what professional support and resources the teachers might need to positively influence the behaviors and performance of this target population. Here we see a positive interplay between the environment, the behaviors of the principal and the students, and the administrator’s competencies to act by developing a policy, reflecting on the effectiveness of that policy on all students, reconsidering his or her knowledge and beliefs, and finally taking new action again.

A second example concerns a new teacher who may have learned a variety of reading strategies that students can use to effectively unpack challenging texts. However, in the teachers’ workroom, the novice teacher may repeatedly hear disparaging remarks about the low performers and their inability to grapple with challenging texts. The novice teacher may challenge her peers’ belief system either inwardly or outwardly. However, she might begin to rethink her own perception of her students and resort to less challenging texts. In this situation, we can recognize the interplay between the conditions of the workroom and the young teacher and how two different results can surface. Unfortunately, we also see how a negative environment can cause new teachers to abandon prior beliefs in favor of more widely held perceptions by more experienced others.

Last, as we reconsider the story about Jason, Korthagen’s model helps us understand the interplay once again. It is evident from Jason’s behavior that he already has the capacity to be compassionate as well as the ability to act on that compassion. Even further, his teacher’s acknowledgment and support led to the reinforcement of his actions. Questions to consider in this scenario raise other possible outcomes. For instance, how might Jason’s competencies to act have been impacted had his teacher responded differently? How might this affect the kind of person Jason was becoming and the beliefs he possessed about homeless people and about social responsibility?

These questions of becoming bring us to the next inner layer—beliefs. Beliefs and values stem from ideas that we construct in our social interactions; consequently they are necessarily skewed or biased. Ideas are formed by our intellect as we interpret our experiences within our own mind-set. Our mind-set, in turn, is shaped by the experiences we’ve had and by ideas presented to us by others. In the above illustrations, both the teacher and the principal reconsidered their beliefs about students. This reconsideration led, in both cases, to the development of new competencies. In each case, the principal and the teacher used what they now believe about challenging students to make new decisions about policies, instruction, and curriculum. However, this is easier said than done, as our beliefs are difficult to uncover, and we tend to be steadfast once we’ve formulated our beliefs. Typically, we need to encounter a new experience that challenges us to question ourselves, and this requires both self-awareness and a willingness to consider that our beliefs are grounded in faulty thinking. Once again, our story about Jason serves to illustrate how beliefs and competencies are linked and impacted by behaviors. Jason seems to possess certain values and beliefs about homelessness. First, he doesn’t seem afraid, nor does he seem to be judgmental of the homeless man’s appearance. In addition, Jason seems to also believe that he has some social obligation toward the homeless. He is compassionate and considers what it must mean to be hungry. The teacher meanwhile shares these ideas and values; he too is compassionate toward the man and in his actions reveals to us his beliefs that govern his role as teacher. In this story, the teacher perceives himself as needing to care about Jason, both for his safety and his compassion for the homeless man. That’s why the teacher accompanies Jason as they walk toward the homeless man. He is affirming Jason’s beliefs and conveying his agreement with social responsibility, kindness, and caring, but he also maintains his role as the protector of Jason’s safety, as despite all good intentions the homeless man is unknown. A new question must now be considered: Had the teacher not shared Jason’s belief about homelessness, he might have discouraged Jason from sharing his lunch. How might this have impacted Jason’s beliefs regarding all aspects of this situation?

The two innermost layers of the onion model are identity and mission. For educators, both layers are represented by such questions as “What kind of leader or teacher do I want to become?” and “What is my central mission as a leader or teacher?” Both layers will be shaped by beliefs and values that the educator develops in his or her life experiences and in his or her professional programs. As both sit at an individual’s core and are built on a foundation of lifelong experiences, they are the most resistant to change. Consequently, it becomes even more imperative that educational preparation programs provide numerous opportunities for preservice leaders and teachers to examine and question the basis for their beliefs, how they see themselves in future roles, and why they were drawn to the field of education initially. This kind of reflective process can assist preservice leaders and teachers to develop new competencies as they learn and grow as professionals.

Finally, we see our framework drawn from Korthagen’s onion model as congruent with the questions posed by prosocial education. Though the behaviors that we desire to see in our society are ones that cause one to care for and about others, what we have come to recognize is that these desirable behaviors spring from the underlying levels of the individual’s onion. By providing an ongoing challenge to our students to reach deeper into their cognitive, social, and emotional levels, it is our goal that our students will see the competencies we facilitate and expect of them and that the competencies will become a default response to the environment in which they live and work. We hope that they see the interplay of how they view themselves, what they believe and value, and the behaviors they demonstrate within the environment, and that this interplay comes from multiple perspectives, as this interplay accounts for their ability to empathize with and advocate for the members of their school or classroom communities.

Research shows that when individuals work and learn in environments that are safe, supportive, and affirming, the end result in schools is better teaching and deeper learning. This is especially important in the diverse society in which we live, given the nature of the current social ills that manifest in our schools. Students arrive at the schoolhouse door often influenced by such factors as bullying, media glorification of stereotypes, poverty, and violence. Each of these has a negative relationship to one’s ability to learn and grow. In addition, the growing impact of technology in the twenty-first century allows for the potential to depersonalize and dehumanize social interactions. For these reasons, it is incumbent upon us as professors of education to prepare future leaders and teachers who have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to bring about ethical change. What follows is a discussion of two courses in our respective programs that we believe accomplish these goals.

Educational Leadership Program: Group Dynamics for School Leaders

There are three strands within the Educational Leadership Program in which I teach: the master’s degree in education; the post-master’s, which leads to principal certification; and supervision, which leads to supervisor certification. Group Dynamics for School Leaders is a course in the master’s degree strand; its purpose is to provide students with a theoretical understanding of group and individual interactions, with practical applications to school situations. The emphasis is on development of the knowledge and skills, including the communication capabilities, that are essential to effective leadership. Social and emotional competencies are the foundation of my approach to meeting course goals.

The first activity presented on the first night of class is one I call “Qualities.” Before we begin our discussion of what social and emotional intelligence are or why these are important competencies to possess and strengthen, I divide the class into four groups, each having a different-color marker. Each group is then given these directions: “You will discuss and generate a list of qualities or traits you believe are in the ideal person in the category you will be given.” Each group knows that they must generate a list, but only they know the category of person they are given. They are not to identify that category on their list in any way. The categories are parent, principal, student, and teacher. After fifteen minutes, the lists are posted in the front of the room, and each student is given a slip of paper with the four categories of person and the four marker colors. They are given a few minutes to match which person goes with which color. Our debriefing is a very valuable tool to bring out what we truly value in people. Most of the lists include qualities such as trustworthy, good listener, honest, impartial, supportive, respectful, takes responsibilities, and open to other points of view. There is usually only one reference to cognitive intelligence. With this as a starting point, it is a natural transition to understanding that what we really want to see in the people with whom we interact are the skills of social and emotional intelligence, and it does not matter what the category of person is; what we want in the ideal parent is very much the same as in the ideal principal, student, and teacher. The ability to be open, honest, and caring are the qualities we believe should be universal.

Following the “Qualities” activity, students complete an anticipatory guide that enables them to self-assess their proficiency in each area of social and emotional intelligence identified in table 17.1. The questions are rephrased as statements, with a Likert scale from 1 to 4 for the guide. The result of this assessment becomes the first step in a self-directed learning study that continues throughout the semester. Self-directed learning is an approach to personal improvement and change developed by Richard Boyatzis at Case Western Reserve University (as cited in Patti & Tobin, 2006, pp. 39–40). This model takes the individual through five questions which Boyatzis refers to as “discoveries.” I have modified his questions for the course to the following:

- Who do I want to be?

- Who am I?

- What is my learning agenda?

- What behaviors, thoughts, and feelings will I practice to the point of mastery?

- Who will be my support system as I develop the change I seek?

Reflecting on the areas of social and emotional intelligence, students select a competency they will work to improve over the semester. They review literature on the area; they create a behavior modification plan and keep a journal of their progress. Finally, they write a paper documenting their progress toward their goal. Obviously a fifteen-week semester is not a long time to see permanent change in human behavior; however, over the seven years of teaching this course, I have seen moderate to great change in the thinking and behavior of the overwhelming majority of my students.

In Group Dynamics I also focus on creating the kind of open, honest communication skills and relationship building that would lead to successful first- and second-order change in schools. First-order change occurs when the change builds on the past structures; it is incremental and requires little deep thinking to understand it as the next obvious step. Actions such as adding a new class to a grade level or changing the textbook for a course because it is out of date are examples of first-order change. Second-order change, however, requires a new way of looking at the present and things that are familiar. It requires flexibility, organizational trust, and time (Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005).

One might well think of the difference between school reform and school transformation that some educators and politicians have called for in education today as good examples of first- and second-order change. The difference may also shed some light on why the change we needed may not come by 2014 as NCLB states, or even 2020 as the proposed reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) suggests.

In Group Dynamics, leadership students learn that change begins on the inside and that they must begin to see themselves as the agents of that change. They are asked to look at their espoused and core beliefs and to recognize the difference between the two—that is, the difference between those beliefs and values they profess versus those which guide their lives. Students develop greater proficiency in active listening, verbal and nonverbal communication skills, perspective taking, and empathy. Administrative in-basket activities and educational scenarios are used to provide them with multiple opportunities to practice these skills and receive constructive feedback on their performance.

Creating effective work groups or restructuring existing groups to be more effective is a major goal of the course. I use the work of David and Frank Johnson (Johnson & Johnson, 2009) to achieve this goal. We discuss the nature of groups, how to move groups from pseudogroups who don’t commit to working together to solve a problem to effective and even high-performance groups, where the product is more than the sum of the individuals who have come together committed to work.

School leaders must rely on the knowledge, talent, skills, and abilities of their faculty to move the school closer to its vision or mission. To be successful, they must learn to work effectively and diplomatically with unique constituent groups such as parents, students, central administration, board of education members, and members of the larger school community. Decision-making strategies, conflict management, and problem solving are also part of the course content.

Interestingly, even though all of my students are presently or at some time in the recent past have been engaged in some educational experience (e.g., teaching, counseling, child study team members), they find it hard to move from their present roles to developing identities as leaders. Addressing colleagues in faculty meetings or leading professional development events may be uncomfortable, and thus they must learn to overcome former self-images and connect to new ones by adopting new behaviors.

We look at levels of knowledge: declarative, which is knowing that something is; procedural, which is knowing how to do something; and conditional, which is not only knowing that it is or how to do it, but also when, where, and why it should be done. These levels are very different and critically important to a school leader. People may know that change is needed; they may know what changes should be made and who should be involved; but do they know why and when is the best time to bring the changes about? Having this level of understanding can make all the difference between the success and failure of an initiative.

My culminating activity is for the students, working in groups of three or four, to devise a role-play based on an actual situation that has occurred in one of their schools. The role-play has parts that are common knowledge to the group and parts that are totally spontaneous so that it mirrors as closely as possible a real-life situation. The students have no idea how their group members plan to act and react in the scenario, though they share with me their personal intentions. It is always informative and enjoyable to see the students act and react as their peers display prosocial and antisocial behaviors during the role-plays. The debriefings, which follow the role-plays, serve to reinforce the skills presented and goals intended in the course.

Linking ISLLC Standards to Prosocial Behaviors

Though I am fortunate enough to have a course specifically dedicated to these types of prosocial skills, the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) standards with which all educational leadership programs must align, provides a compelling rationale for these types of skills to be embedded into most leadership courses (Council of Chief State School Officers, 1996). Below we explain how other courses in the Educational Leadership Program address prosocial education through meeting ISLLC standards.

Standard 1: An education leader promotes the success of every student by facilitating the development, articulation, implementation, and stewardship of a vision of learning that is shared and supported by all stakeholders.

Standard 4: An education leader promotes the success of every student by collaborating with faculty and community members, responding to diverse community interests and needs, and mobilizing community resources.

The first course in our program, Introduction to Educational Administration, requires students to develop an educational platform—a vision of schooling—which they will continually refine as they progress through each course in the program. In Group Dynamics, they create an “elevator speech” where they must be able to articulate their vision accurately and succinctly.

Standard 2: An education leader promotes the success of every student by advocating, nurturing, and sustaining a school culture and instructional program conducive to student learning and staff professional growth.

In Curriculum Theory and Practice, the students develop an action plan to address the use of best practices and research-validated approaches to improve the academic achievement of K–12 students at a specific grade level and content area in a school setting. Here, the focus is improvement across the continuum, which is bringing the partially proficient to proficient and the proficient to advanced proficiency, as well as continuing to challenge the advanced proficient students.

Standard 3: An education leader promotes the success of every student by ensuring management of the organization, operation, and resources for a safe, efficient, and effective learning environment.

Standard 6: An education leader promotes the success of every student by understanding, responding to, and influencing the political, social, economic, legal, and cultural context.

Modules in both School Finance and School Law address issues of equality and equity, how they are different, and what consequences there might be to schools that don’t understand these differences.

Standard 5: An education leader promotes the success of every student by acting with integrity, fairness, and in an ethical manner.

All courses within the program address the responsibility of school leaders to always act with the best interests of their students, faculty, staff, and community in mind. Students examine and reexamine their values, beliefs, and thoughts for inner integrity and for fairness and ethical behaviors toward others. Each and every one of the ISLLC standards calls for the school leader to advocate for and be supportive of others, thus making the leader prosocial at least in spirit. School leaders should be models for the faculty and staff, students, parents, and the larger school community. If we are not doing this in our educational leadership programs, we are not preparing school leaders who can be successful in our twenty-first-century schools. And anyone who knows anything about U.S. history knows that schools have been and will more than likely continue to be the place our society turns to address and correct the problems we face as a nation. Therefore, school leaders will continually face an environment steeped in change, both first and second order. It is imperative that they be able to adjust and respond to that change from a foundation of a deep understanding of who they are and what they believe and value, that they have a range of competencies at their disposal, and that they have the awareness to behave in appropriate and effective ways.

Secondary Education, Undergraduate Teacher Preparation: Schools and Communities

At our liberal arts college in New Jersey, I teach three different courses in our undergraduate teacher preparation program, which has been intentionally designed to consider one primary foundational question: What does it mean to teach in different contexts? This question is central to our program for various reasons. First, our college undergraduate population is over 75 percent white, and our secondary education program serves 85 percent white students. This population is largely drawn from New Jersey suburbs, and while our students tend to be open-minded, most of them have had little experience working with diverse groups. Many of our students report living in primarily white communities, or if they do live in a diverse community, they report completing high school in an educational track that was largely populated by white students. Consequently, neither group has attended classes with students of color, nor were they friends with people of color. Many of my students express an interest in teaching in urban schools, but few have encountered what difference truly means in terms of social interaction patterns, communication styles, and the cultural needs of urban students. In addition, they do not have any experience with the demands made on students who live in urban neighborhoods.

Therefore, Schools and Communities was designed to raise my students’ self-awareness of their own biases and privileges and instill social awareness of the needs of their future students who may have an entirely different cultural knapsack. Course readings provoke students to learn self-management as they are drawn into lively and sometimes heated debates over authors and situations that challenge their mind-set. Toward the end of the course, the students begin to consider how their new awareness has caused them to rethink their moral obligations to manage relationships in entirely different ways than they had expected.

Of Goleman’s (1995) four areas of emotional intelligence identified previously, this course intends to specifically target the questions identified in table 17.2. Second, this course is also designed to meet the New Jersey Professional Teaching Standards (NJPTS; New Jersey Department of Education, 2004) required of all teachers who are to be certified in our state. The four standards this course meets are as follows:

Table 17.2. “Reflecting on My EQ” (Patti & Tobin, 2006, p. 210)

|

Self-awareness How well am I aware of my own feelings, beliefs, and values? Do I recognize how my feelings, beliefs, and values shape my mind-set? Do I see how my emotions affect my interpretation of other’s behavior? Can I hear you when I am given positive and negative feedback? Self-management Am I aware of how my mind-set influences how I respond to others? Do I set high expectations for myself and others? Can I get out of the box and embrace new challenges? |

Social awareness Can I see, hear, and observe the perspectives of others? Am I sensitive to the differences in others? Can I listen without judgment? Am I aware of the political current of classrooms/schools? Can I see and understand power relationships? Do I understand how culture influences classrooms? Do I know what people need to thrive? |

|

Relationship management Do I see the strengths of others? Can I motivate others? Can I build nurturing relationships and a safe learning community? Can I work well in a team and help others to do the same? |

Learning theory. Teachers understand how children and adolescents develop and learn in a variety of school, family, and community contexts and provide opportunities that support their intellectual, social, emotional, and physical development (NJPTS No. 2).

Collaboration and partnerships. Teachers build relationships with school colleagues, families, and agencies in the larger community to support students’ learning and well-being (NJPTS No. 9).

Diverse learners. Teachers understand the practice of culturally responsive teaching (NJPTS No. 3).

Reflective practice. Teachers participate as active, responsible members of the professional community, engaging in a wide range of reflective practices, pursuing opportunities to grow professionally, and establishing collegial relationships to enhance the teaching and learning process (NJPTS No. 10).

Third, these professional standards are congruent with our own professional goals as teacher educators. As our nation becomes increasingly diverse, the cadre of new teachers entering our public schools is disproportionately white. Therefore, we see it as our professional obligation not only to develop my white students’ self- and social awareness in order for them to engage in prosocial behavior, but also to provide them with the requisite knowledge and skills needed to enable them to engender prosocial behavior in their future students. While these goals inform our entire secondary education program, this chapter does not provide sufficient space for me to articulate how we enact these goals programmatically at all three levels of our students’ educational experience. Therefore, we will be focusing on Schools and Communities, a course taken at the sophomore level.

Purpose of Schools and Communities

The purpose of Schools and Communities is to study the complex sociocultural context of classrooms by examining the intricate relationships between teachers and students. The course goals are to examine how classrooms, as dynamic, social environments, are co-constructed by teachers and students and for my students to learn how this dynamic impacts student learning. At the heart of this understanding is the examination of values and beliefs. I begin the first day with an activity that involves my students writing about their educational experiences, those that have been memorable and those that have been regretful. From this activity, students recognize that their memories of teachers have little to do with content but rather resonate with the classroom climate the teacher constructed and the instructional strategies the teacher implemented.

As future middle and high school teachers who hope to inspire passion for their subjects, my students are surprised that “content” is not among the list of elements drawn on the blackboard. Instead, their list is peppered with phrases inherent to prosocial behavior: caring, listening, supportive, aware of student needs, and responsive. Also among this list are other phrases that we typically associate with instruction but which in actuality are undergirded by a teacher’s capacity to manage classroom relationships; students identify instructional strategies and assessments that target their intellectual and social needs as students. Phrases include cooperative learning, creative projects, and real-world application. As we discuss in class the interplay between emotional and intellectual needs, the students begin to expand their understanding of what constitutes the work of teachers.

During this first session, students also read “Looking at Classroom Management through a Social and Emotional Learning Lens” (Norris, 2003). This important essay situates prosocial behavior within the greater body of competencies teachers must develop in order to be effective managers of twenty-first century classrooms. Last, we explore their present thinking about what knowledge, skills, and attitudes might change as a result of the content in this course. In the second session, the students learn about Korthagen’s (2004) model of change, and on that day we continue the conversation about how the remainder of the course rests on the continuous reexamination of their beliefs and values, how their beliefs and values are shaped, and, as they encounter course readings that challenge their mind-sets, how their beliefs are changing. The second year this course was taught, I conducted formal interviews with students. In those interviews, the students spoke of the success of these course goals; significant numbers of students reported growing self- and social awareness and a new moral imperative that obligates them to act on this newfound awareness as future teachers (Gosselin & Meixner, 2007).

Schools and Communities Instruction

So how is this newfound awareness and moral imperative aroused and shaped? We know from Korthagen’s (2004) model that for awareness or beliefs to change, individuals must encounter experiences and develop competencies to reshape their belief system. This is a tenuous process that if done poorly can backfire and in fact requires the professor to behave prosocially herself by recognizing that she needs to be self- and socially aware, be prepared to act on that awareness, and manage classroom relationships so that students feel safe to express and grapple with their intellectual conflicts. This involves tolerance of comments that are sometimes infuriating, a willingness to “put on hold” frustrations that surface when students utter naive social explanations, and patience to introduce concepts only when students reveal a readiness to listen to authors who anger them. One of my own learnings involved waiting to assign Peggy McIntosh’s (1990) “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” until one or two students raise the specter of privilege within their own lives. It always happens; the course readings and assignments set this up.

In addition to the goal of instilling a prosocial mind-set, the preservice teachers are expected to develop interpretive and critical reflective skills for understanding how teachers’ and students’ lives, beliefs, and values are shaped by community and school experiences. The intent of this approach is to shift the students’ interpretation of classroom dynamics and student achievement from explanations that stem from psychological models such as student motivation to sociologic models that identify competing value systems as a root cause of poor student performance. These intellectual skills are achieved through the analysis of case studies and ethnographies with a heuristic device, close readings of theoretical texts, and the completion of a fieldwork experience in a public school setting where they conduct an analysis of classroom culture.

Questions that guide the choices for course readings and classroom discussions include the following:

- What does it mean to be an educator in a diverse society? How does this definition affect the lived experiences of teachers and students and drive the organization and culture of classrooms and schools?

- How do family and community culture shape the values, beliefs, and mores that we use to define our role as educators? In light of that knowledge, how is our identity and mission as teachers redefined?

- How do different cultural beliefs and values possess more or less power in shaping school practices? How does power influence the classroom practices, pedagogical choices, and curriculum designs we choose?

- What is the relationship between white privilege, school design, and power? How does the hidden curriculum influence achievement and define our lives in schools? How do we unmask classroom and school practices that encourage the isms in social structures such as race, class, gender, and sexual orientation?

Case studies and ethnographies are carefully selected to generate opportunities that will challenge my students’ social imagination to create new narratives that explain others’ points of view. There is an intentional scaffolding of a complex nature of classroom and social dynamics that they encounter in these course readings. First, the students read case studies (Rand & Shelton-Colangelo, 2002) that amplify problems that a student teacher may encounter in a classroom that pertain to racism, sexism, heterosexism, or stereotyping. These case studies are very short and showcase the kinds of classroom problems the students may actually encounter when they step into the role of student teacher. For example, one case study illustrates a curriculum choice that stirs parental objections over the viewing of Beloved in a junior year social studies classroom. In another case study, the student teacher unintentionally sets different expectations for a Christian Fundamentalist student who is disrespectful of her more liberal peers. These case studies call upon my students’ ability “to put their emotions on hold” while we interpret the social nature of the situation found in the case study as a prerequisite to considering the next step the student teacher may need to consider in order to resolve the dilemma. This interpretative process begins by examining assumptions on which the student teacher in the case study acted; we unpack our own emotional reactions aroused by the case study, and then we analyze the case study using the heuristic device (see next section).

The second type of case study we interpret and analyze is drawn from Sonia Nieto’s (2004) Affirming Diversity. These case studies provide the preservice teachers the chance to encounter beliefs and values very different from their own. Adolescents in these case studies grapple with conflicting home and school values that impact their identity development and their school achievement. Conflicts stem from differences deeply rooted in competing social norms such as biracial, gay/lesbian, or immigration status. Frequently my students recall peers who were seemingly at the margins, who were labeled and rendered invisible in their own high schools. However, one case study involves a teenager who reflects the students in this course: a middle-class white female who espouses color blindness as a mind-set. This case study best reflects my own students’ initial and well-intended understanding of social dynamics and also stands in stark contrast to the other case studies. Therefore, we read it last; this positioning of the reading requires my students to juxtapose their beliefs squarely with newly encountered differences. Many recognize themselves immediately and begin to question the moral import of color blindness as well as how this mind-set renders the experience of others invisible. They begin to recognize the harm that color blindness may cause and subsequently begin to query about “what more they now need to know.”

Third, the students read and analyze one ethnographic study using the heuristic device. These ethnographies are read independently, and students work in small groups to prepare a class presentation that draws on their new interpretative skills as they analyze how social norms have defined the lived experiences of the adolescents in the ethnographies and how school and community tensions have impacted their achievement as students. A brief list of ethnographies I have drawn on include Bad Boys (Ferguson, 2001); Con Respeto (Valdes, 1996); Hopeful Girls, Troubled Boys (Lopez, 2002); Schoolgirls (Orenstein, 1995); Asian Americans in Class (Lew, 2006); and Color of Success (Conches, 2006).

In addition to the case studies and ethnographies, the preservice teachers read a range of theoretical texts that provide them with an educational language to analyze classroom dynamics on an intellectual and practical level.

Last, the students apply their knowledge and analytic frames to an actual classroom setting. The students observe a secondary classroom in a local public school once a week for a period of five weeks. While on the surface this appears to be a very short period to draw any conclusions, the students’ reports indicate that they have internalized the knowledge and skills they encounter in this course. During their classroom visits, the students take copious notes that replicate teacher and student actions over the instructional period. Elements they focus on include the manner in which the teacher welcomes and begins class, the activities the teacher has designed, how well the teacher communicates directions and lesson concepts, the quality of questioning, student engagement, the emotional climate of the classroom, and the teacher’s classroom management style. The students are provided with a “handbook” that defines each of the elements that comprise their observations, and they are instructed on the sequencing and focus of each observation they conduct.

The Heuristic Device

The heuristic device (see table 17.3) used to analyze the case studies and the fieldwork observation assignment were course tools created by Terry O’Connor, who was among the original designers of this course. Terry, now deceased, devoted his professional career to teaching and learning especially in the domain of social interaction patterns; one of his seminal works is among the course readings. The heuristic device consists of two analytic frames that are conjoined to identify the hidden problem in the case study. The two frames, educational structures and educational themes, are used to shape the analysis or thesis of the problem the case study presents. Why use this device? My findings are that without a tool to force the students to think socially and politically, they default to explanations that result in student motivation or student behavior as the root problem. In essence, they tend to respond stereotypically and urge others to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. These analytic frames demand that they think otherwise. Students compose three different graded essays of three different case studies using this heuristic device. The use of this device is practiced regularly in class.

|

Education Structures |

Education Themes |

|

Classroom management: Organization of space and materials Student management: How are students treated? Curriculum: How is subject matter organized? Learning patterns: What are the methods of instruction? Assessment patterns: What are the formal and informal assessment tools? Social patterns: How do the students interact throughout the lesson? Adaptation patterns: How is instruction differentiated? How are emotions responded to? How are social structures addressed? Counseling relationships: How does the teacher respond to individual needs? Peer friendships: How are student groups organized to facilitate a range of peer interactions? |

Personal development of students: Are students’ psychological, intellectual, and social development actively supported? |

|

Social development: Are students learning how to work effectively with others? |

|

|

Actualization and agency: Are students learning they can positively influence their social worlds? |

|

|

Bureaucracy: Is the school actively creating an environment conducive to all learners? |

|

|

Effectiveness: Is the school or teacher demonstrating the ability to teach all learners? |

|

|

Fairness: Are there concerted efforts made by the school and teacher to provide everyone with a fair chance to succeed? |

|

|

School community: What are the characteristics of the school or classroom culture? |

|

|

Family relations: Is the school or teacher working to close the communication gap with families and the surrounding community? |

|

|

Equity: Are all students afforded the resources needed to be successful? |

|

|

Pluralism: How does the school or teacher capitalize on the assets the diverse community offers? |

|

|

Change: Are the school and teacher adapting to new technology and the new social landscapes of the community it serves? |

When reading case studies and ethnographies, students are asked to identify the central issues presented in the study by selecting what they believe is the most important educational structure and educational theme impacting the interactions. They are informed that no correct choice exists but that the facts support some structures and themes better than others. Once they’ve chosen their structure and theme, they compose a thesis statement and then defend their choice based on the facts only. They also draw on the theoretical literature we have discussed in class to additionally support and deepen their analyses. Finally, they identify the next step needed to resolve the problem and then explain how this case study has influenced or clarified their values and mission as future teachers.

As we work through these case studies, the students lament about not having sufficient information. We discuss this real-world problem and the role self-awareness and self-management play in examining assumptions and actions we are inclined to jump to when our emotions alone guide our decision making. The assignment demands that they suspend these hasty judgments as they consider all the facts, the details that are absent, and puzzle over the root cause of the problem. This puzzling is what I believe supports their growth most, as it asks them to reflect deeply on their ideas, the conclusions they draw from those ideas, and the hidden assumptions embedded in that thinking. Since this work is largely done privately or in small groups, students are afforded the emotional safety to engage in exposing and interrogating their personal values and beliefs as they reconsider them.

The intended end result of my course is for my students to grow in their understanding of classrooms as constructed political spaces that involve a great deal of negotiation between teachers and students, to realize that their future students will not enter their classrooms as blank slates ready to be filled with neutral knowledge and truths but rather as whole individuals with cultural assets; that it is their moral obligation as teachers to construct a well-functioning and supportive classroom that includes their own students’ cultural knowledge, beliefs, and values; and that they generate opportunities, include resources, and draw upon instructional approaches that are flexible and address the intellectual and sociocultural needs of the students they will be teaching. Conversations, both formal and informal, reveal this growing mind-set among the sophomores as they exit my classroom at the end of the semester. In subsequent courses and finally in student teaching, I find that this mind-set has been internalized and serves to inform their classroom practice as student teachers. For others, this process needs continuous reinforcement and reminders for the lightbulb to remain lit. My hope and mission as a professor of education is that this mind-set will continue and follow them into their own classrooms upon graduating from our college.

Summary

Our chapter began with the story of Jason, a young man whose sense of concern, perspective taking, and ethical actions motivated him to share his lunch with a homeless man he passed on the street. From this story, we drew out the qualities that characterize the kind of educator we work to shape for twenty-first-century schools. These qualities include caring, empathy, and self-awareness—values that are inherent to prosocial behavior.

We then discussed the connection between prosocial behavior and Korthagen’s (2004) model of change as the framework we have drawn upon to design experiences in our respective programs to develop those qualities in our students. Using Korthagen’s model, we explain the bidirectional nature of the self, the self’s inner layers, and the environment. It is important to understand that while it is the outermost layer of the self (i.e., behaviors) that is observable, it is the inner layers that engender the behaviors that one demonstrates. At the same time, factors within the environment may stir up the inner layers of the self, causing different behaviors to be observed. Had the homeless man not been in the environment, Jason would not have shared his lunch. So what we really want our students to understand is that while what they bring to their schools and classrooms is important, the environment is also having an impact on them. Therefore, it is very important that they understand who they are, what they believe and value, and what their mission is in order to determine the course of action that will generate a positive end result.

The descriptions of the two courses in our programs illustrate approaches that we have found to be successful in promoting prosocial behaviors in our students. It is our hope that in reading these descriptions, others will be stimulated to first examine their own practices for what they are already doing effectively and then consider other methods that they can use to promote prosocial education in their students.

References

Conches, G. Q. (2006). Color of success: Race and high-achieving urban youth. New York: Teachers College Press.

Council of Chief State School Officers. (1996). Interstate school leaders licensure consortium: Standards for school leaders. Washington, DC: Author.

Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The roots of prosocial behavior in children. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson, A. A. (2001). Bad boys: Public schools in the making of black masculinity. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam.

Gosselin, C., & Meixner, E. (2007, November). Facing developmental roadblocks in multicultural preparation in a secondary education program. Paper presented at the conference of the National Association of Multicultural Education, Baltimore, MD.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F. P. (2009). Joining together: Group theory and group skills (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Korthagen, F. A. J. (2004). In search for the essence of a good teacher: Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(1), 77–97.

Lew, J. (2006). Asian Americans in class: Charting the achievement gap among Korean American youth. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lopez, N. (2002). Hopeful girls, troubled boys: Race and gender disparity in urban education. New York: Routledge.

Marzano, R. J., Waters, T., & McNulty, B. A. (2005). School leadership that works: From research to results. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

McIntosh, P. (1990, Winter). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Independent School Magazine, 49(2).

New Jersey Department of Education. (2004). New Jersey professional standards for teachers and school leaders. Trenton, NJ: Author. Retrieved November 28, 2011, from http://www.state.nj.us/education/profdev/profstand/standards.pdf

Nieto, S. (2004). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon.

Norris, J. A. (2003). Looking at classroom management through a social and emotional learning lens. Theory into Practice, 42(4), 313–318.

Orenstein, P. (1995). Schoolgirls: Young women, self-esteem, and the confidence gap. New York: Anchor Books.

Patti, J., & Tobin, J. (2006). Smart school leaders: Leading with emotional intelligence (2nd ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing.

Rand, M., & Shelton-Colangelo, S. (2002). Voices of student teachers: Cases from the field (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon.

Valdes, G. (1996). Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools. New York: Teachers College Press.