Chapter 19

The District Superintendent’s Role in Supporting Prosocial Education

Sheldon H. Berman, Florence C. Chang, and Joyce A. Barnes

Across the nation, superintendents feel pressure to raise students’ academic performance. No superintendent can—or would want to—give short shrift to these expectations. Yet the role of the superintendent is also to see the big picture for the long term. Doing so requires thoughtful attention to the social settings in which student learning takes place. Having recently been appointed to my third superintendency, I have witnessed the difference that prosocial education can make in districts large and small. I have also learned that such a focus can succeed only if the superintendent is philosophically and operationally committed to it and provides leadership to the staff, board, and community in several key steps: framing the vision for prosocial education, policy development, understanding and applying the findings of research, selecting or modifying high-quality social education programs appropriate to each grade level, integrating the academic and social curricula (including service learning and cultural competence), and supporting and recognizing teachers and administrators through professional development, as well as the allocation of classroom time, the collection of data, and the analysis of program impact.

In the interest of promoting improved student outcomes in other districts, I am pleased to share the following discussion of my work in the area of prosocial education in two demographically disparate school systems. I appreciate the contributions made by coauthors Florence C. Chang, evaluation specialist, who collected and analyzed much of the data, and Joyce A. Barnes, specialist, who assisted in transforming this information into a comprehensive report. Both of these colleagues are with the Jefferson County Public Schools in Louisville, Kentucky.

—Sheldon Berman, EdD, superintendent, Eugene (OR) School District 4J

To perform at their highest level, students need to feel safe to take intellectual risks, they need the social skills to exchange ideas and collaborate with others, and they need to feel supported by the peers and adults who form their community of learners. Although school district leaders feel tremendous public pressure to concentrate on the academic curriculum, the social environment of the classroom and the school are equally critical to student learning. In fact, the nature of the classroom social environment can determine whether learning will thrive or flounder. The social environment creates the foundation on which productive learning can occur.

Grounded in Research

Phillip Jackson and other educational theorists referred to this social curriculum as the “hidden curriculum of schooling” because it communicates to children what is valued, what behaviors are acceptable, and who has power and authority in the classroom. Since Jackson’s pioneering work (1968), we have learned much about the impact of the social environment of the classroom on children. In essence, whether we are explicit about how we construct that social environment or not, it creates the conditions for both social and academic learning. Therefore, it is far better that educational leaders thoughtfully consider how best to create an environment that supports children’s social, emotional, and academic growth than to leave this key factor to chance.

The research supports this concept. Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, and Schellinger (2011) examined over two hundred school-based programs, involving over 270,000 students, that aimed to improve the social and emotional climate in schools. All the studies reviewed had a control group, and about half of the studies utilized a randomized design. The meta-analysis found that, compared to the control groups, students in schools that promoted a supportive school climate demonstrated on average an eleven-percentile-point gain in academic achievement.

Not only has school climate been shown to impact student achievement, but a positive school climate has also been shown to be related to a variety of outcomes, including reduced student absenteeism, reduced suspensions and behavior problems, lower rates of alcohol use, reduced psychopathology, and increased student connectedness to school (Battistich, Solomon, Kim, Watson, & Schaps, 1995; Battistich, Solomon, & Watson, 1998; Kasen, Johnson, & Cohen, 1990; Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004; Reid, 1982; Schaps & Solomon, 1990; Solomon, Battistich, Kim, & Watson, 1997; Wu, Pink, Crain, & Moles, 1982). A study by Rimm-Kaufman, Fan, Chiu, and You (2007) found that the Responsive Classroom approach in elementary schools led to significant gains in reading and math, with the greatest impact being in those schools that had utilized the Responsive Classroom approach for at least three years. The Search Institute, a nonprofit group focused on the well-being of young people, also conducted a series of studies on the impact of a caring school climate. In these studies, a caring school climate was associated with higher grades, higher engagement, and lower grade-retention rates (Scales & Leffert, 1999).

In addition, many experts point out that it is not simply the impact on test scores that matters, but the impact on student motivation that is the ultimate outcome of forming successful lifelong learners (Cohen, 2006). A positive school climate has been shown to increase academic motivation to learn (Goodenow & Grady, 1993), whereas a less supportive school climate has been shown to decrease student motivation (Eccles et al., 1993). The degree to which students feel safe, respected, and connected to school has a profound impact on whether students are able to and desire to learn (National School Climate Council, 2007).

Therefore, district leaders have good reason not only to think through how best to support a positive and productive environment for students, but also to think carefully about the strategies and social structures that teachers and administrators use to create such an environment in the first place.

Social Development in Practice

What also emerges clearly from the research on prosocial development is that it is necessary, but not sufficient, to teach children basic social skills. Children must learn these skills within the context of a caring community in which they feel connected to and cared about by others, where conflict resolution and collaboration are modeled in the daily realities of the classroom, where students have a voice in decision making, and where they have opportunities to act constructively and make a difference for others and the community at large. In essence, they need to experience a sense of community and the opportunity to put into practice—in real situations—the positive social skills they are learning in the classroom. However, creating this kind of environment is just as challenging as providing high-quality reading and math instruction. It requires the use of research-based strategies embedded within the school day, emanating from thorough professional development of faculty and administration in the use of these strategies and in understanding children’s social development.

To arrive at this point in the classroom entails working at multiple levels simultaneously. At its heart, teachers need to build a sense of community in the classroom wherein both the adults and the students feel that they are known and valued as individuals. To achieve this goal, students need opportunities to learn such social skills as viewing a situation from another’s perspective, solving problems collaboratively, and resolving conflicts positively. Even as adults, we sometimes struggle with these skills; therefore, teaching them to children requires self-reflection and a predisposition toward personal growth. How teachers and administrators interact with students, deal with conflict situations, and work collaboratively with students to solve problems is critical to the success of their efforts to build community and nurture social development. In fact, the way teachers and administrators communicate and work with other adults in the building, as well as with students, not only models these behaviors for students but makes an important statement about what adults value and what standards they hold for themselves.

In addition, young people need to experience the effectiveness of these skills in the world around them. While it is vital that the safety of a caring community first be evident in the classroom, in order to change and shape their own behavior, students need to see the utility of these skills on the playground, in the cafeteria, on the bus, in their neighborhoods, and with their parents, relatives, and friends. Applying these skills in multifaceted situations requires practice and dialogue. Classroom time is wisely spent enabling students to discuss their experiences and suggest strategies for how to best handle conflict or problem situations. It also helps to create situations in which students are of service to others, so that they not only demonstrate the helping behaviors they are learning but experience the affirmation of their own efficacy in assisting others. Finally, social development efforts need to engage parents through strategies that bring them into that sense of community that has been created in the classroom and school and that assist them in learning parallel strategies for addressing issues at home.

Just as there is a developmental sequence for the teaching of reading and math, there is a developmental sequence in teaching prosocial skills and social responsibility (Berman, 1997). Consistency among teachers and administrators is important—very much like the consistency we encourage parents to have in their child rearing at home. Employing a systemic and consistent approach across classrooms and across schools enhances the individual efforts of teachers and ensures the significance of the impact it has on student learning. It also facilitates students’ integration into a new setting as they change schools, either when moving up a level or as a result of family mobility, and discover that the same social norms apply. It is the role of leaders, particularly the superintendent, to set a vision that encompasses prosocial development and to set district priorities so that this vision is achieved.

A Systemic Approach

As a superintendent first in Hudson, Massachusetts, and later in Louisville (Jefferson County), Kentucky, I had the opportunity to put this research into practice. In both districts, we initiated comprehensive and systemic social development programs to teach students basic social skills and build a caring sense of community in the classroom and school. While these programs were in part homegrown, they were intentionally based on the rich experience and effective professional development provided by other organizations that are recognized leaders in this field. Hudson and Jefferson County also incorporated social development into their mission statements and theories of action.

Small District

In Hudson, we combined several programs to achieve our prosocial education goals, presaging a core message of this handbook (see chapter 1). The preschools adopted the Adventures in Peacemaking curriculum produced by Educators for Social Responsibility. This engaging set of activities provided a solid foundation among the early childhood population. The elementary schools chose a program from the Committee for Children—entitled Second Step—and supplemented it with conflict resolution material from Educators for Social Responsibility. Second Step focuses on teaching children to manage their anger in constructive ways and to demonstrate empathy for others. Beginning at the kindergarten level, the program offers thirty lessons per grade that involve students in role-playing and discussions. The intent of these lessons is to help children learn to identify the feelings of others and to reflect on and practice appropriate ways of responding to situations. Second Step also includes a parent component to stimulate related conversations and behaviors at home. A study of this program, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that it was successful in decreasing physical and verbal aggression and in increasing prosocial behavior (Grossman et al., 1997).

Where Second Step takes a direct-instruction approach to developing students’ social skills, the Responsive Classroom program—developed by the Northeast Foundation for Children—targets teachers’ strategies for structuring and managing their classroom. Nearly all of the elementary and middle school teachers in Hudson were trained in this program, which provides teachers with a framework for creating a classroom environment that fosters the integration of prosocial skills. Based on a belief that the social and academic curricula are equally important and integrally connected, Responsive Classroom guides teachers to effectively use class meetings, rules and their logical consequences, classroom organization, academic choice, and family communication to create a caring classroom environment even as they foster children’s academic and social success.

Service Learning

Of course, the point of prosocial education is not simply to facilitate classroom interactions and learning but to prepare students for positive social interactions in all aspects of their lives. To enable students to hone and apply their emerging skills within the community, the Hudson school district initiated a comprehensive service learning program. However, service learning was not interpreted as a single-event participation in local charitable efforts, such as collecting canned goods for the food bank or raising money for medical research. Rather, it became an ongoing activity that was woven into each year’s curriculum, promoting students’ mastery of core concepts while providing a means for authentic assessment. Since service learning was designed into a unit of study from the outset with clear expectations and outcomes, it not only supported the acquisition of content knowledge but enabled students to apply the social skills and prosocial behavior they were learning at school to a context in which they were actually of service to others. This service learning gave them a sense of empowerment and grounded their social skills in the real life of their community.

High-quality service learning programs can assume many forms. In Hudson, each grade level designed a project and integrated it into the districtwide curriculum, thereby giving students consistent experiences with service learning throughout their school years. For example, as kindergartners were learning essential math and reading skills, they wrote and laminated math and alphabet books to be sent to children in Uganda. Fourth graders who were studying ecosystems performed field research and environmental reclamation work in nearby woodlands and wetlands. Fifth graders served as reading buddies for first graders and for special needs students. Sixth graders studying ancient Greek and Roman cultures staged an educational culture fair for younger students. Ninth graders grappling with their civics course developed and implemented proposals that addressed a variety of community needs. What made this service learning approach particularly effective is that the students’ experiences were deeply integrated into the regular curriculum and so concurrently furthered curricular, prosocial, and civic engagement goals.

Large District

To accomplish similar goals in Jefferson County (Louisville), we have blended the preschool Adventures in Peacemaking program from Educators for Social Responsibility and the Caring School Community (CSC) program of the Developmental Studies Center for grades K–5 with several other programs into a program we call “CARE for Kids.” The program is aimed at providing significant and engaging learning opportunities that allow students to experience membership in a safe and caring community. In 2010/11, a total of seventy out of ninety elementary schools and twenty-one out of twenty-five middle schools were implementing the program.

CARE for Kids Principles

CARE for Kids embodies six core principles:

- At the heart of a caring school community are respectful, supportive relationships among and between students, educators, support staff, and parents.

- Learning becomes more connected and meaningful for students when social, emotional, and ethical development is an integral part of the classroom, school, and community experience.

- Significant and engaging learning, academic and social, takes place when students are able to construct deep understandings of broad concepts and principles through an active process of exploration, discovery, and application.

- Community is strengthened when there are frequent opportunities for students to exercise their voice, choice, and responsible independence to work together for the common good.

- Classroom community and learning are maximized through frequent opportunities for collaboration and service to others.

- Effective classroom communities help students develop their intrinsic motivation by meeting their basic needs (e.g., safety, autonomy, belonging, competence, usefulness, fun, pleasure) rather than seeking to control students with extrinsic motivators.

CARE for Kids Components

The primary activities and components of CARE for Kids include the following:

- Caring classroom community: developing classroom community and unity building through activities such as cooperative and collaborative learning across content areas and class meetings.

- Morning meetings: special type of class meeting where students greet each other, share experiences in their lives, listen carefully to others, discuss the agenda for the day, and build relationships with their classmates.

- End-of-day meetings: brief closing meetings in which students reflect on their day and share something that stood out for them, something they learned, or something that someone did to help another person.

- Developmental discipline/logical consequences: proactive, preventive approach to discipline that uses a teaching/learning approach with an emphasis on relationships, modeling, skill development, moving students to self-control, and responsibility.

- Homeside activities: designed to stimulate conversations between students and their family members.

- Buddies: matches older students with younger students for collaborative mentoring activities facilitated by the teachers.

- Schoolwide activities: designed to link the students, parents, teachers, and other adults in the school with a focus on inclusion and participation, communication, cooperation, helping others, taking responsibility, appreciating differences, and reflection.

At its core, the program in Jefferson County engages children in a variety of thoughtful class meetings that provide students with a voice in their classroom community. These class meetings teach basic social skills and help students grow socially and ethically through dialogue about classroom and school issues. Morning meetings drawn from the Responsive Classroom program build community among students. End-of-day meetings ask students to not only reflect on their day academically but also to reconnect with the sense of community established in the morning. Teachers use a model of developmental discipline that provides logical consequences for behavior and gives children opportunities to reflect on and correct their behavior. In addition, the program engages older students in service opportunities through mentoring younger students. Finally, the program engages parents in this community-building and social development initiative through activities that children take home to complete with their parents or other family members, and through schoolwide activities that engage parents and caregivers in social and academic events at school. Although modified at the middle school, these same key elements provide a continuum from preschool through eighth grade. As at Hudson, the comprehensiveness and systemic nature of the program nurtures prosocial development in a consistent and developmentally appropriate way.

Integration with Academic Curricula

In addition, both districts selected academic curricula that support and further the development of social development goals. For example, the social and collaboration skills that students acquire through the prosocial programs are critical to the effective use of such inquiry-oriented and collaborative learning math and science programs as Investigations in Number, Data, and Space; the Connected Mathematics Project; and the Full Option Science System (FOSS), which are used in Jefferson County. At the same time, these inquiry-oriented academic programs facilitate students’ social development by giving them practical and immediate application of their social skills. The schools in both Hudson and Jefferson County introduced a reading comprehension program entitled Making Meaning and a writing program entitled Being a Writer, developed by the Developmental Studies Center. Through these programs, students read high-quality literature with prosocial themes and then learn strategic comprehension and writing skills through activities that are structured to also teach social skills. To further enrich the reading program, we added historical fiction that depicts people facing social and ethical dilemmas and choosing to make a difference through service or social activism. Examples of these fictional texts include Uncle Jed’s Barbershop by Margaree King Mitchell, The Long March by Marie-Louise Fitzpatrick, Coolies by Yin, and Pink and Say by Patricia Polacco. Any district that is weighing the idea of layering programs to create this type of comprehensive, systemic effort should remember that one of the essential rubrics that must be used in selecting curricular programs is the quality of social and collaboration skill development embedded in the program. This alignment enhances the consistency between the academic and social curricula.

Cultural Competence

There is yet another strategy integrated into the CARE for Kids program that is key to fostering a socially responsive classroom for educators across all grades, and that is cultural competence (see chapter 18). Most teachers and other educators are the product of middle-class homes and have little or no experience with the economic, family, and language differences that are present among so many students, particularly in urban school districts. Consequently, teachers’ level of caring often far outstrips their level of understanding. Unacknowledged and unaddressed, the lack of cultural sensitivity and competence among both adults and students can undermine students’ sense of worth and security, particularly for those most at risk. To address this underlying barrier to student success, Jefferson County has undertaken a systemic effort to promote cultural competence. Through intensive workshops and institutes, staff members at all levels of the organization are engaging in simulation activities and frank conversations designed to help them confront stereotypes and prejudices and understand different lifestyles and cultural norms. As teachers, in particular, are sensitized to the diversity among students’ everyday lives, they are more likely to make valid observations about why some children respond as they do and to find more effective ways of reaching out and building strong relationships with these students. Cultural competence training also enables teachers to connect students’ cultures to the curriculum, thereby assisting children to feel safe and respected within the classroom setting. However, the impact is clearly felt in the prosocial behavior it models and encourages in students, laying the foundation for all students to act in a socially caring and responsible way toward others.

High School Implementation

In Jefferson County, as in Hudson previously, the program took on a different form at the high school level, which can be a challenging level for building community because of the larger student population; nevertheless, personalization of the secondary experience remains a critical element. In both districts, the ninth grade is taught by teams of teachers in a freshman academy model that supports students’ transition from middle school to high school. The teachers share a common planning time that enables them to discuss and address the needs of students, meet with parents, and plan ways to build a sense of community among students. Students are a part of a smaller and supported community of learners in which they feel known and respected.

In addition, each district formed small learning communities for students in grades 10 through 12 that extend ongoing support in an environment where each student is known by the adults in the school and feels a part of the larger student community. These clusters, as they were known in Hudson, or schools of study, as they are known in Jefferson County, do not restrict students’ ability to enroll in a wide range of courses, but instead provide a community of interest among students and teachers around broad career themes. Again, the opportunity to connect with peers and adults who share similar career interests encourages students to engage in collaborative work and demonstrate respect for the contributions of others. The high school years present an apt time for students to consider the broader social and ethical implications of individual actions on their school, their community, and the larger social world. Again, in both districts, we developed a core ninth-grade social studies civics course that poses the essential question: “What is an individual’s responsibility in creating a just society?” This course draws heavily from the Facing History and Ourselves curriculum (see chapter 18 case study A), which engages students studying the roots of genocide, including the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide. By asking how it is that a nation of everyday people can allow genocide to become state policy, this course confronts young people with the human potential for passivity, complicity, and destructiveness. It poses significant ethical questions and raises awareness of the ramifications of injustice, inhumanity, and the abuse of power. On a broader level, because it helps discourage students from accepting simple answers to complex problems, the curriculum also supports inquiry-based course work in other classes. In the process of studying the individual and social forces that have spawned genocides throughout history, students come face to face with their own potential for passivity and complicity, their own prejudices and intolerances. As the classroom dialogue promotes new perspectives and social reasoning skills, students develop a deeper sense of moral responsibility and a stronger commitment to participate in making a difference. They come to view their school as a microcosm of society, and they reflect on their own responsibility for creating a more just and compassionate school community.

As a result of the comprehensive layering of each of these programs, students build positive relationships with peers and adults and develop prosocial and conflict resolution skills. However, what is actually most important is that students experience what it means to be a responsible member of a community and they come to realize that their action—or lack of action—has an impact on others around them and on the quality of life in the community.

Sustainable Implementation

Implementation of any new curriculum or program requires thoughtful planning and in-depth professional development. It requires staging the integration over time so that teachers and administrators can make sustained and steady progress. As with any program, that integration is best supported by high-quality curricula and professional development. Most important, the program needs to have the strong backing and encouragement of district leadership so that staff know they can take the risks and make the effort necessary to create an effective approach to reaching its stated goals.

Allocating Classroom Time

One of the immediate tensions that emerges in implementing a comprehensive social development program is that it requires teacher–student interaction time. Initially, class meetings, morning and end-of-day meetings, buddy programs, and community-building activities appear to deduct time from instruction. Over the long term, however, the impact on instruction is precisely the reverse of what initially seemed to be the case. Because students are better able to work together and resolve their interpersonal differences, there are fewer discipline issues in the classroom, fewer disruptions, and far greater efficiency and productivity in cooperative and collaborative classroom activities and projects. Teachers also become adept at interweaving academic and social reflection into the class meetings. Essentially, as teachers implement the program, they start viewing the class meeting time as critical instructional time. Not surprisingly, attendance improves and tardiness declines because students don’t want to miss the important and productive social time with their classmates.

In addition, programs in social development are absolutely critical to the smooth and effective functioning of inquiry-based curriculum programs in math and science and of literacy programs such as Readers and Writers Workshops. These programs are designed to build student engagement and interest and make extensive use of group work and group problem solving. The skills students develop through a social development program enable teachers to more effectively use these programs and enable students to gain the conceptual benefit these programs were designed to offer. Although social development programs require making a commitment to regularly scheduled time during the school day and week, that time facilitates higher and deeper levels of learning in a more productive environment.

Professional Development

Building community and resolving conflicts are not simple skills for teachers to develop. The focus of most universities’ preservice teacher development programs is on managing the classroom and planning lessons to effectively teach content. Few new teachers have either background or instructional experience in the area of prosocial development (see chapter 17). For veteran teachers, focusing on social development by engaging students in classroom problem solving can cause them to feel that they are relinquishing control of the classroom and the order they have so carefully established. One of the powerful lessons of teaching is that by engaging students, one gradually acquires more—but less obvious—control as students assume greater responsibility for the interaction between peers and the management of the classroom. However, this process takes time, quality professional development, and on-site coaching by those who have had success in building a sense of community in their classrooms.

Nurturing social development requires facilitating problem-solving and conflict-resolving dialogue among students. It requires being aware of one’s own tendency to intervene with a solution instead of allowing the students to find their own workable solutions. It requires reflection on the way the class day is structured, the opportunities students may have to make choices, and the language and approach the teacher uses in difficult situations. Just as encouraging student thinking about an investigation in science requires attention to asking the right questions, leaving sufficient wait time to stimulate student thought, and organizing the lesson in a way that engages student discovery and reflection, facilitating social problem solving requires similar instructional thoughtfulness. In essence, teachers are supporting deeper levels of conversation about the social dynamics of the classroom and school so that children can begin to better understand and take a positive role in those dynamics. Therefore, successful, sustainable implementation necessitates that teachers acquire new proficiencies. To do so entails providing them with opportunities to participate in high-quality professional development, observe teachers proficient in these skills, be observed by and mentored by colleagues, and collaborate with other teachers on implementation.

Program Selection

Essential to high-quality implementation is the use of well-developed, research-based programs that have been shown to produce the desired results. If a program is of high quality, it can be instrumental in furthering a teacher’s knowledge and skill by providing the guidance and structure to support effective implementation. Although Hudson and Jefferson County selected a particular set of programs to create the right blend of skill instruction and modeling for our circumstances, there are a number of excellent programs available to schools that are equally effective. Such programs as the Educators for Social Responsibility’s Resolving Conflicts Creatively Program, the Wellesley College Stone Center’s Open Circle, and others are effective avenues for teaching these skills. In each of these programs, not only are students given direct instruction in basic social and emotional skills, but the whole school becomes involved in creating a caring community that models respectful and empathetic behavior. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) has published valuable reviews of programs and is an important resource organization in supporting program selection and implementation.

Superintendent’s Role in Leading the Leaders

In addition to allocating adequate time, using high-quality programs, and supporting teachers through in-depth professional development, sustainable implementation requires the superintendent’s leadership in policy development and administrative support and recognition. The pressures of school and district accountability based on state standards and tests are ever increasing. It is easy to lose focus on anything that appears extraneous to what is being tested. Unless administrators endorse and encourage a focus on social skills comparable to that on academic skills, teachers will not feel they can take the time necessary to hold the kinds of meetings and pursue the kinds of activities that promote social skill development. District and building-level administrators have to clarify that this area is also a priority and that, without a focus on social development, students won’t achieve at the levels we hope for in their academic work. District-level administrators need to allocate the resources for program materials, professional development, and coaching. In both Hudson and Jefferson County, I designated a central office director to facilitate this work, and coaching was provided either through teacher mentors or staff developers. This support made an important statement to teachers that the district was going to provide the resources necessary for them to be successful in implementing a comprehensive and high-quality social development program.

Superintendent’s Role in Policy Development and Recognition

It is also important that this emphasis be built into policy and regular forms of recognition for teachers and students. Over the course of several months and multiple conversations with staff and board, I led both districts to develop thoughtful mission statements and theories of action that addressed the concept of social development and established its role within the curriculum. There were regular school board presentations about the program and its impact on students. The districts recognized teachers and students for their success, both by honoring high-quality implementation through articles and videos and by service awards and recognitions for students. Although public recognition may seem ephemeral, it makes an important statement to those who receive it as well as to those who observe that the administration and school board members take the time to acknowledge that this is important work for the district to be doing.

Data Collection

Results matter, no less for social development than for academic development. As a small district, Hudson did not have the capacity to do in-depth program evaluations. Although there was improvement in attendance, behavior indicators, and academic performance, the district was in the midst of numerous reform initiatives, and it was impossible to determine the degree of impact the initiatives around prosocial development had independently. However, since Jefferson County possesses an experienced and talented group in its research and evaluation department, assessment of the CARE for Kids program was tracked from its inception. As CARE for Kids was being implemented, the logic model for outcomes was that the implementation of the program would first yield positive differences in school climate. As students felt more supported and respected, the next logical outcome would be to see improvements in the areas of behavior, attendance, and achievement. The data for the program support this logic model. The implementation of the program has resulted in positive growth in school culture, improved attendance and behaviors, and, finally, improved academic achievement.

Baseline Data

Prior to the rollout of CARE for Kids, it was important to have the baseline data and program-aligned assessment tools developed so that (1) the program could be closely monitored for quality implementation and (2) school data could be examined pre- and post-implementation of the program. The year prior to the CARE for Kids implementation, the district’s Comprehensive School Surveys (CSS) were redesigned so that the surveys gathered not only perceptions of academic content, but also perceptions of the social-emotional, civic, and moral connections that are vital to student learning. Each year since 2007, the district has administered the redesigned CSS to all school staffs, intermediate elementary students, and middle school students. Students answer on a 1-to-4 scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree) the extent to which they agree with statements such as “I really like other students in my school” and “I enjoy going to school.” The CSS surveys have consistently yielded strong reliability coefficients (Muñoz & Lewis, 2009). Because the survey is given annually, it was possible to examine the change in any school’s culture pre- and post-implementation of a program.

Classroom Observations

In addition to the survey assessment of school climate, another critical aspect of successful rollout of the program was the development of an implementation rubric to identify and define observable components of the program. The district specialists for CARE for Kids worked alongside the district research department to develop a reliable walk-through tool. Subscales include routines and procedures (e.g., classroom norms displayed), relationship (e.g., respectful interactions between teachers and students), language (e.g., utilization of reflective language), and student-centered environment (e.g., students collaborating with each other). The walk-through instrument was used to randomly observe schools each year, so we had data on how to better support implementation. For example, after the first year of the program, it was observed that while relationships were strong, schools were struggling with having student-centered classrooms. Focused support was developed to address that component the following year, and as a result the largest gain seen in the walk-throughs in 2010/11 has been in the area of student-centered environment. The walk-through instrument also served as a tool to the in-house school leadership teams to provide internal support.

Survey of Implementers

Each year, the district’s research department also administered an annual survey to gather perceptions and implementation levels of the CARE for Kids program. Because Jefferson County is such a large district, it was not feasible for district personnel to observe every teacher implementing the program. The annual survey allowed staff the opportunity to identify aspects of the program that were working well and areas in which they needed support. By utilizing all three pieces of data—the CSS, walk-throughs, and CARE for Kids surveys—the district was able to continuously understand how to better support implementation. For example, after the first year, one of the insights that emerged from the surveys was that teachers almost unanimously agreed that their principals were supportive of the program. However, the key to higher implementation was found among teachers reporting that their principals actually observed their classrooms and provided feedback on implementation. Based on this observation, we shared with principals that their support alone was insufficient; instead it was crucial that they visit classrooms and have a continuing dialogue with their staff on areas of improvement.

Program Impact: School Culture

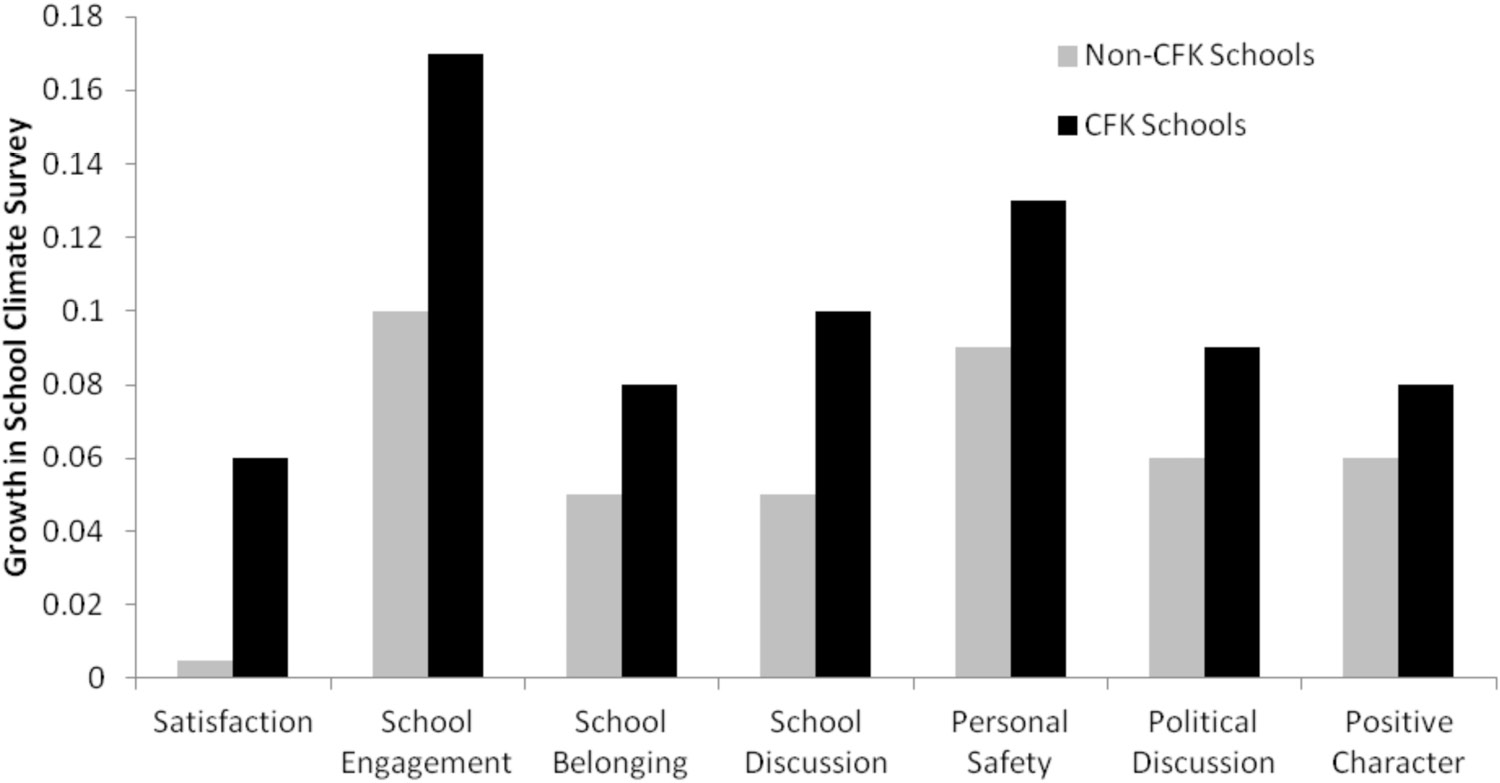

In terms of outcomes, the district is large enough to allow for matched comparison groups of schools that have implemented a program and schools that have yet to implement the program. Analyses of the data each year (including from 2010/11) reveal statistically significant differences in growth of school culture, with CARE for Kids schools outperforming the non–CARE for Kids schools in growth of positive school culture across the subscales. Students who attended CARE for Kids schools showed more growth in the areas of school satisfaction, school engagement, school belonging, school discussion, personal safety, political discussion, and positive character than did students at non–CARE for Kids schools (see figure 19.1). The growth represented a difference of one-half to one full standard deviation in school climate, depending on the subscale.

Figure 19.1. Growth in student comprehensive survey subscales.

When examining attendance and suspensions for elementary schools, data show that there was a significant correlation between CARE for Kids implementation and attendance and suspensions. The higher the implementation of CARE for Kids (as defined by staff survey and walk-through data), the more likely the schools were to increase student attendance and decrease suspensions. At the middle school level, the findings were similar, with high implementers of CARE for Kids decreasing their number of suspensions at a significantly higher rate than did low implementers of CARE for Kids.

Correlations between implementation data and change in attendance and suspensions showed that higher implementation was significantly related to growth in attendance and a decline in suspensions, r(54) = 0.44, p < .01 and r(54) = −.37, p < .05, respectively. The average attendance rate at an elementary school in 2009/10 was 95.07 percent. When examining high and low implementers of CARE for Kids, high implementers showed an increase of .05 percent in attendance, while low implementers showed a decline of .16 percent. High implementers of CARE for Kids also decreased their number of suspensions, while low implementers had an overall increase in the number of suspensions from pre- to post-implementation of CARE for Kids.

Program Impact: Academic Achievement

In the area of academic achievement, the Kentucky state achievement test is given each year in April and yields an academic index score (on a scale of 0 to 140) that is reflective of the percent of students who score at the novice, apprentice, proficient, and distinguished levels in reading and math. At the elementary level, schools that had implemented CARE for Kid for two years outpaced a matched comparison group, as well as the district as a whole, in their growth in reading, social studies, and writing on the 2010 Kentucky state achievement test. For elementary schools that had been implementing CARE for Kids for only one year, high implementers improved significantly more in reading and math than did low implementers. At the middle school level, high implementation of CARE for Kids was also related to higher academic achievement. Table 19.1 shows the difference in the index scores for reading and math for high and low implementers of CARE for Kids at the elementary level.

Table 19.1. Implementation of CARE for Kids and Impact on Academic Achievement

|

Group |

Reading Index Change |

Math Index Change |

|

Low implementers |

.86 |

−4.19 |

|

High implementers |

3.09* |

1.84* |

*Indicates statistically significant difference between high and low implementers.

Data examining the impact of CARE for Kids on school climate and academic achievement also support the logic model. Schools that were higher implementers showed higher growth in school climate, and schools that showed the growth in school climate were schools that made academic gains. Although this evaluation is for the initial stages of implementation, it clearly indicates that the high implementation of a comprehensive prosocial development program has an impact on school culture, attendance, behavior, and academic achievement. However, the most important result of this research is that students enjoy school more and feel more comfortable in their classrooms because they have learned basic social skills that allow them to collaborate more effectively and learn from each other.

Program Impact: Teachers and Students

Perhaps the most illuminating data from the evaluation of CARE for Kids come from the voices of the students and teachers. Focus groups and surveys were conducted with teachers and students in CARE for Kids schools. Table 19.2 shows themes and quotes that have emerged from the data.

Table 19.2. CARE for Kids Program—Impact on Teachers and Students: Voices from the Field

|

Theme |

Quote |

|

CARE for Kids Teachers |

|

|

Social skills |

“Better behavior through community building on the kids’ part has allowed for more time to have on-task activities, which is directly attributed to CARE for Kids.” “CARE for Kids has improved the way children interact with each other and adults in the building. They just seem happier.” “It enables the children to talk with each other, respect each other, and live among the diversity.” |

|

Ready to learn/academic |

“CARE has had the greatest impact on my teaching. I have learned to interact to a greater extent with my students and in turn they with each other.” “Students are very happy and well adjusted, which creates an atmosphere for learning.” “CARE for Kids is a great program—it opens up the communication in the classroom by starting and ending each day with a meeting to allow the students to reflect on their school day and what they learned.” |

|

Students in CARE for Kids Schools |

|

|

Caring community |

“Teachers take time to get to know you and learn what you are interested in.” “In morning meetings, you get noticed before the day starts.” “We have learned how to communicate and respect each other more.” |

|

Interactions with other students |

“I like working with partners because I get to know them better. I can learn from them, and they can learn from me.” “I have changed—I never used to show respect for others.” “My class is like a family and having brothers and sisters. Sometimes we fight, but we always work it out.” |

Not only have our efforts shown positive results, but our results confirm the growing research base showing that consistent programs such as these have a strong impact on students’ academic success, social-emotional skills, and sense of belonging in school.

Conclusion

While each district is unique, the role of the superintendent is key to whether or not prosocial education becomes a pivotal component of the curriculum. The superintendent must develop a strong understanding of the vision among the leadership team; communicate commitment and support; guide curricular integration through program review and professional development; assist the board, community, and parents to understand and reinforce the effort; and promote sustainability through evaluation of impact.

Our work with children has a profound and long-lasting impact. Thoughtfully constructing the social environment so that young people grow up knowing what it means to be responsible and caring members of a community is equally important to preparing them for the contribution they will one day make to their community’s economic life. In fact, educators’ failure to help young people see that they, too, are responsible for building viable communities—where people can resolve differences positively, work cooperatively with others to solve significant community problems, and reach out in caring ways to support others in need—may actually compromise the essence of civic life in the United States.

If you stop people on the street and ask them to define the mission of education, they are almost certain to respond with such phrases as “teach fundamental academic skills” or “prepare students for a future career” or perhaps “motivate students to be lifelong learners.” All of these responses are good ones; yet they are less than complete, because education has a broader purpose as well. To be truly educated, people need to fully comprehend their capability and responsibility in the myriad social settings in which they find themselves. Nurturing students to assume their vital role as reflective and caring citizens cannot be an afterthought of teachers, principals, or superintendents. Our work in structuring the classroom social environment should be at least as intentional as our work in formulating our math and language arts curricula. To do less is to leave the larger mission of education unfulfilled.

A critical facet of my role as superintendent, and that of all superintendents and district and school leaders, is to continue to remind our staff, our parents, and our communities that there is a larger mission to public education. That mission is to give young people the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to sustain our democracy and help create a safer, more just, and more peaceful world, the kind of world we all want for our children, the kind of world we should be shaping in our classrooms today.

References

Battistich, V., Solomon, D., Kim, D., Watson, M., & Schaps, E. (1995). Schools as communities, poverty levels of student populations, and students’ attitudes, motives, and performance: A multilevel analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 627–658.

Battistich, V., Solomon, D., & Watson, M. (1998, April). Sense of community as a mediating factor in promoting children’s social and ethical development. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA.

Berman, S. (1997). Children’s social consciousness and the development of social responsibility. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Cohen, J. (2006, Summer). Social, emotional, ethical, and academic education: Creating a climate for learning, participation in democracy, and well-being. Harvard Educational Review, 76(2), 201–237.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Midgley, C., Reuman, D., MacIver, D., & Feldlaufer, H. (1993). Negative effects of traditional middle schools on students’ motivation. Elementary School Journal, 93(5), 553–574.

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71.

Grossman, D. C., Neckerman, H. J., Koepsell, T. D., Liu, P., Asher, K. N., Beland, K., et al. (1997). Effectiveness of a violence prevention curriculum among children in elementary school: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277(20), 1605–1611.

Jackson, P. (1968). Life in classrooms. New York: Hart, Rinehart, and Winston.

Kasen, S., Johnson, P., & Cohen, P. (1990). The impact of social emotional climate on student psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18(2), 165–177.

Muñoz, M., & Lewis, T. (2009). Comprehensive School Surveys (2008–09): Strengthening organizational culture. Retrieved on March 1, 2011, from http://www.jefferson.k12.ky.us/Departments/AcctResPlan/PDF/ReportsForCSSWebSite/CSS_Eval_REPORT2009.pdf

National School Climate Council. (2007). The school climate challenge: Narrowing the gap between school climate research and school climate policy, practice guidelines, and teacher education policy. Retrieved on March 1, 2011, from http://nscc.csee.net

Pianta, R. C., & Stuhlman, M. W. (2004). Teacher–child relationships and children’s success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review, 33, 444–458.

Reid, K. (1982). Retrospection and persistent school absenteeism. Educational Research, 25(2), 110–115.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Fan, X., Chiu, Y.-J., & You, W. (2007). The contribution of the Responsive Classroom approach on children’s academic achievement: Results from a three year longitudinal study. Journal of School Psychology, 45(4), 401–421.

Scales, P. C., & Leffert, N. (1999). Developmental assets. Minneapolis, MN: Search Institute.

Schaps, E., & Solomon, D. (1990). Schools and classrooms as caring communities. Educational Leadership, 48, 38–42.

Solomon, D., Battistich, V., Kim, D., & Watson, M. (1997). Teacher practices associated with students’ sense of the classroom as a community. Social Psychology of Education, 1(3), 235–267.

Wu, S., Pink, W., Crain, R., & Moles, O. (1982). Student suspensions: A critical reappraisal. Urban Review, 14(4), 245–303.