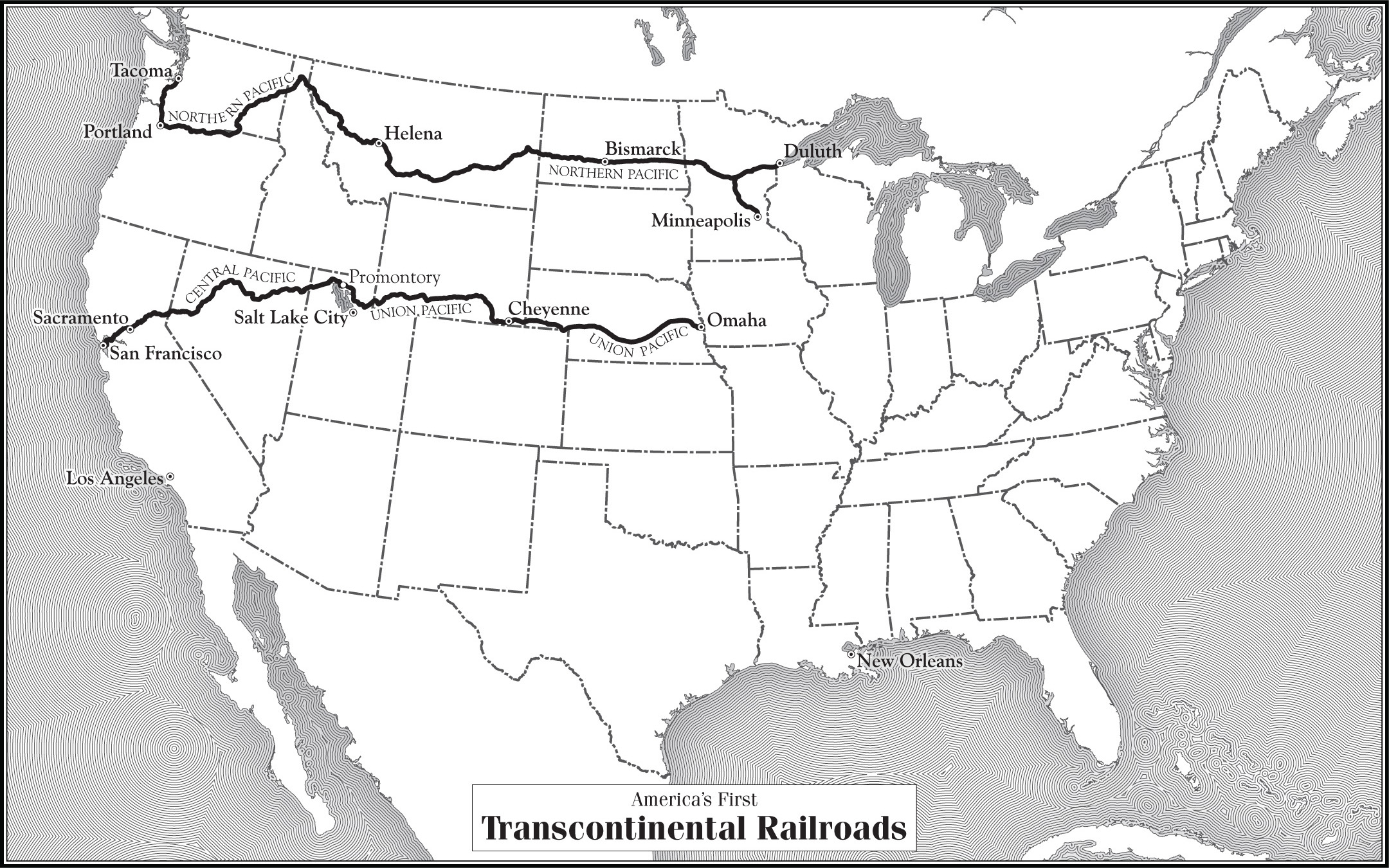

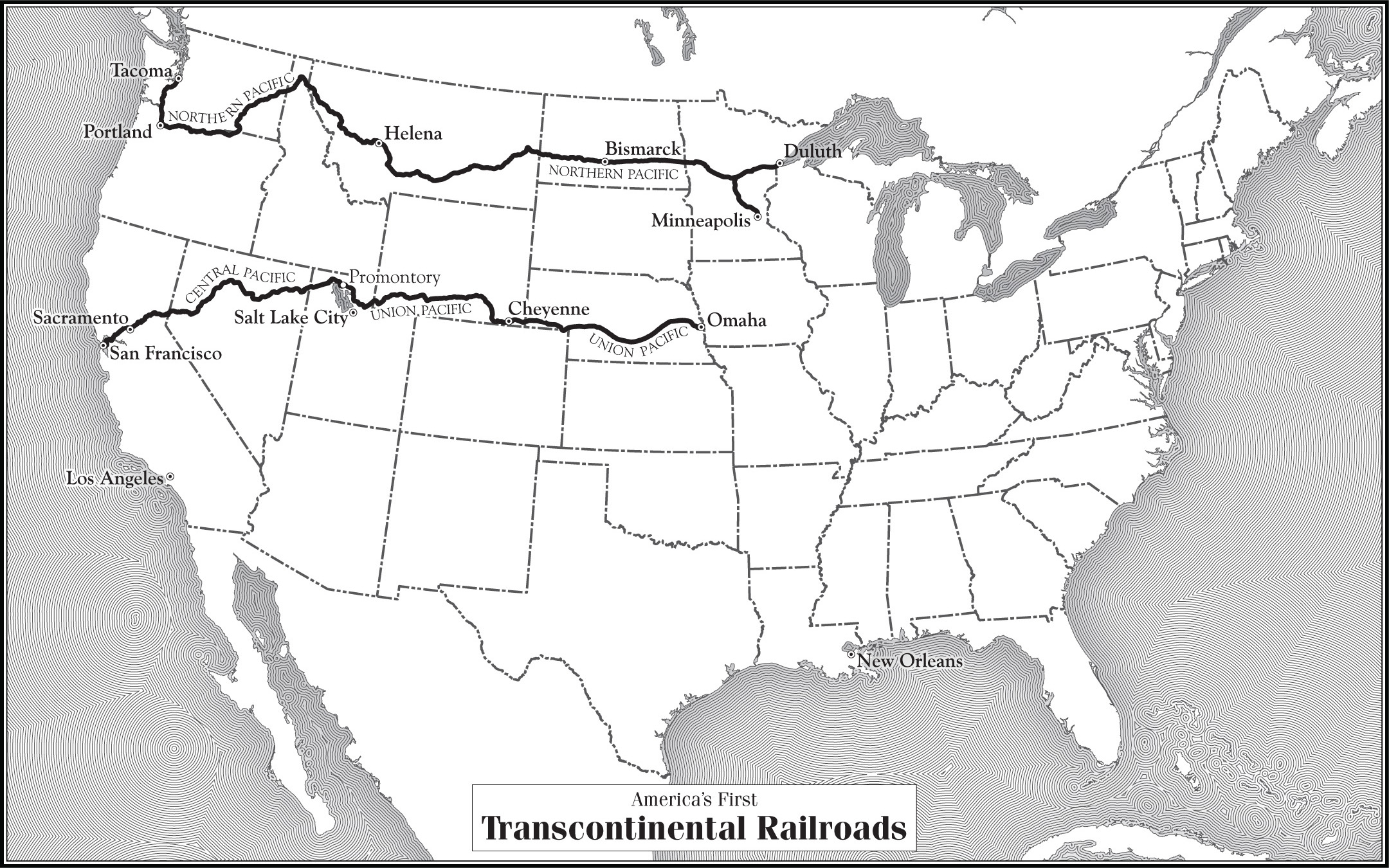

OF ALL THE transcontinental railroads built after the Civil War, the Northern Pacific had the oldest pedigree. Its route, which roughly followed the path of the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804 to 1806, had been favored by Asa Whitney, the leading proselytizer of transcontinental rail as an expression of America’s destiny, in the 1850s. Of the five alternatives surveyed by order of Congress in 1853, that northern route, reaching from Lake Michigan to the Columbia River and terminating on the Oregon coast or at Puget Sound, traversed the territory richest in economic potential—a treasure trove of timberlands, mineral deposits, and arable acreage.

As Whitney acknowledged, the route also crossed the homelands of bellicose Indian tribes, especially the “numerous, powerful, and entirely savage” Sioux, who “occupy and claim nearly all the lands from above latitude about 43 degrees on the Mississippi to the Rocky mountains.” This he held to be a virtue in disguise, for building the railroad offered white America the best means of taming the tribe. Efforts to “civilize” smaller tribes in the region, he explained, had been stymied by the tribes’ ability to take refuge in Sioux territory, but the incursion of the railroad and the settlers coming in its wake would close off this stratagem. “This road would put them asunder so that they cannot meet,” he wrote; “and we can then succeed in bringing the removed and small tribes to habits of industry and civilization. . . . Their race may be preserved until mixed and blended with ours, and the Sioux must soon follow them.” Thus would the whites’ sacred duty to bring “the savage, the barbarian, and the heathen” to Christianity be fulfilled.

The four other transcontinental routes mapped by the surveyors crossed desolate wastes offering little to lure homesteaders. By 1862, moreover, when Congress began seriously debating whether to fund a transcontinental railroad, the Confederate rebellion had placed the southernmost route out of bounds. Politics and expedience argued for a middle path, the prairie route ultimately traced by the Union and Central Pacific. Congress was anxious to bind far-flung California to the Union with iron rails to quell a movement there favoring the Confederacy. And the prairie route had the virtue of familiarity, for it had carried the forty-niners west during the California gold rush.

But the dream of a northern transcontinental railroad was not dead, only slumbering. It was reawakened by a promoter named Josiah Perham, who had originally applied for the congressional charters that had been awarded instead to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific. Perham subsequently transferred his application to a route running between Maine and Oregon. For his “People’s Pacific Railway Company,” he proposed to raise a hundred dollars each from up to a million small individual investors, with a down payment of only ten dollars required.

Perham was considered a “visionary” like Asa Whitney—and as in Whitney’s case, the term described him as a man in the grip of delirium. He forswore the government bond financing that propped up the Union and Central Pacific roads, instead securing for the People’s Railroad a commitment for government land grants of 12,600 acres for every mile of completed track in the states of Wisconsin and Minnesota and twice as much in the territories of Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and Washington. Despite his conviction that the small investments of a million Americans and the resale of land to settlers would be sufficient to finance the road, the absence of a direct government subsidy would become an albatross for Perham’s enterprise. So too would the congressional mandate that the railroad begin construction within two years, complete at least fifty miles per year after that, and be entirely finished by the Fourth of July, 1876.

Within a year of obtaining his charter, Perham’s vision was in a shambles. The stock subscription campaign having failed miserably, he was unable to begin surveys of the right of way, much less start construction, so no land grants were forthcoming and there were no land sales to generate income. Perham was pushed out of the company by a clique of New Eng-landers hoping to revive its fortunes by appealing to Congress for a direct government loan. Perham would die destitute in 1868, another railroad pioneer broken and embittered by dashed dreams.

The new owners soon discovered that congressional taste for advancing millions of dollars to speculative railroad ventures had soured after the handouts to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific. The northern road’s land grants were deemed useless as collateral by would-be investors, who recognized that forty-seven million additional acres of northern prairie could only overfill a homesteading market struggling to absorb the millions of arable acres in Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas already granted to railroad builders.

Casting about desperately for a financial lifeline, the Northern’s promoters soon turned, inevitably, to Jay Cooke. The most eminent financier in the country, widely regarded as the savior of the government during its gravest financial crisis, Cooke would put their dream on a realistic footing over the next five years—and then ride it to his ruin, taking the national economy with him.

WHEN THE CIVIL War began, Jay Cooke was an obscure banker who had just opened his firm’s doors in Philadelphia. He was born in Sandusky, Ohio, on August 10, 1821, the son of a prominent lawyer and state legislator. The region was still mostly wilderness; Eleutheros Cooke, Jay’s father, had erected the first stone house in town, choosing a site on the shore of Lake Erie where Ogontz, the burly local Wyandot chief, had built his wigwam before the tribe was removed to a reservation forty miles inland. The tribe still remained part of the community, regularly returning to the lakeside to pick fruit from the trees they had planted in years past and to collect their federal stipend. “Old Ogontz did himself and us the honor of occasionally sojourning for a few days on the spot where he had once dwelt in his wigwam,” Cooke would recall in the memoirs he scribbled by hand in the last years of his life. “He was allowed to camp in our barn. . . . I was his favorite and occasionally was mounted on his shoulders for a ride.”

Jay Cooke, the nation’s preeminent financier at the end of the Civil War, was ruined in the Panic of 1873 by his investment in the Northern Pacific Railroad.

While still in his teens, Cooke was invited by a brother-in-law to join his shipping company in Philadelphia. The business failed in the Panic of 1837, but young Cooke’s diligence had been noticed by a local banker, Enoch Clark, who brought him into his firm as a clerk. Cooke was a quick study with a native talent for business and finance. Upon Clark’s death in 1856 he was appointed executor of the estate, and managed to bring the firm through another financial crisis, the Panic of 1857, “with an absolutely unruffled temper” while more established banking houses failed around him. This disposition would serve him well through some of the more challenging times to come.

The US government’s finances were at a low ebb as the country careened toward war. On July 1, 1860, John Sherman of Ohio, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, informed his colleagues that the government carried $64.8 million in debt but had only $3.6 million in its coffers. The dire situation did not come as a surprise to the lawmakers. “Most of the members are aware,” Sherman said, “that the Government has not been able to pay, for the last week or two, our own salaries.” He recommended borrowing $10 million. But that would be a pittance compared with the Union’s war needs over the next five years.

Cooke’s entrée into the Union financing market came via his brother Henry, who back in Ohio had been a friend and business partner of Salmon P. Chase, Abraham Lincoln’s first treasury secretary. Having a strong sense of patriotism and an abolitionist streak, Jay Cooke was determined to help the Union cause. In May 1861 Pennsylvania was struggling to place $3 million in bonds to finance its participation in the war. Cooke stepped in and by the end of June had sold out the entire issue.

“It is regarded as an achievement as great or greater than Napoleon’s crossing the Alps,” Jay boasted to Henry, who made sure it came to Chase’s attention. The treasury secretary named Cooke the exclusive agent in Philadelphia and New Jersey for a $150 million federal bond sale in 1861. Cooke perfected a sales technique based on three pillars: patriotic ballyhoo, an appeal to legions of small investors being introduced for the first time to the concept of building their nest eggs with government securities, and a relentless publicity campaign. Newspaper editors were made to understand that if they desired advertising from Cooke and his partners, they would integrate his tub-thumping sales pitches for the bonds into their news columns, no questions asked. In Washington, meanwhile, Henry Cooke lavishly entertained news reporters, inviting them to his Georgetown home to be “filled full to the brim not only with edibles and bibibles, but with the glorious financial prospects of the future.”

Cooke would ultimately be credited with placing more than $1.5 billion in government debt during the war, roughly one-quarter of the total issued. His methods sometimes excited negative remark, as when he attempted to place an article in national newspapers with a headline describing the government debt as “a national blessing.” The slogan was deplored by sober investment advisers for tempting small investors into imprudence, especially since the government’s fiscal management had already come under fire. The title was eventually toned down to read “How Our National Debt May Be a National Blessing,” and the article widely distributed.

The article and its headline were the handiwork of Sam Wilkeson, a reporter on the staff of the New York Tribune with a peerless talent for spinning seductive fancies from the barest facts, or no facts at all. Cooke had hired Wilkeson at Henry’s urging to assist with publicity for a $600 million Union bond issue. “His specialty should be the manufacture of editorials, letters, notices and so forth,” Henry told Jay, with an implicit emphasis on the word “manufacture.” This marked the start of a long association between banker and publicity man, even if Wilkeson’s rhetoric sometimes went too far, as in the case of the “national blessing” article. (It would not be the last time.)

The pace of bond sales slowed considerably as the war drew to an end, amid a general contraction in the market ascribed to expectations that the vigorous inflation of the war years would yield to deflation as the government tried to get its books back in shape. The greater threat to financial stability came with Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865. Cooke ordered his agents to support the market the next day, a Saturday, through unlimited purchases of “all United States bonds thrown on the market,” pledging to cover any losses personally. The effort worked. As Cooke related in his memoirs, “it required the purchase of less than twenty millions in the space of seven or eight days to end the panic. . . . The spectacle was presented to the world of a nation with its credit unimpaired and its securities advancing in price while suffering from a terrible calamity.”

By the time the war ended Cooke was the most famous financier in the country. His services to the Union had earned him as much as $10 million. No one was ever sure of the total, but Cooke’s profits were sufficient to allow him to build a grand mansion of fifty-two rooms in the countryside just outside Philadelphia, which he christened Ogontz after the Wyandot chief who had carried him on his back so many years before, and to acquire Gibraltar Island in Lake Erie, just offshore from Sandusky, as a summer retreat. The firm of Jay Cooke & Co. won esteem as a paragon of financial stability, its founder reigning over the financial sector as an intimate of leading figures in business and government, including, after the election of 1868, President Ulysses S. Grant.

The promoters of the northern transcontinental road hankered after not only Jay Cooke’s money but his reputation. “The manner in which [the railroad’s securities] had been ‘hawked about’ in New York and elsewhere . . . had combined to give a taint to the whole concern,” one promoter observed. “It could only be made reputable by being taken up by new parties.” Cooke at first regarded the railroad men skeptically, once even reprimanding Henry for making commitments to them behind his back.

By fits and starts, however, the Northern Pacific wriggled into Cooke’s favor. The railroad men were looking for a savior, and in Jay Cooke they happened upon a man with a messianic self-image. “Like Moses and Washington and Lincoln and Grant,” he would write in his memoirs, “I have been—I firmly believe—God’s chosen instrument, especially in the financial work of saving the Union . . . and this condition of things was of God’s arrangement.”

Cooke had also become enthralled with the economic potential of the upper Midwest. In 1868 he visited the western end of Lake Superior. The land he saw was rich, though the physical settlements were decrepit. The old town of Superior, nestled against the Wisconsin state line, had declined to a population of three hundred after peaking at about eight hundred before the Civil War. The town had been founded by wealthy Southerners looking for “a watering place where they could be free to take their slaves with them,” having been excluded from Saratoga, New York; Newport, Rhode Island; and other resorts where slaves were not admitted. Duluth, its sister township on the Minnesota side, comprised six or seven dilapidated wooden shacks. “The appearance of the towns is ludicrous, zigzag, rude, etc., and half filled with Indians,” Jay Cooke wrote his brother Henry. But he compared their prospects favorably to those of his native town, Sandusky. To thrive, all they needed was a railroad.

The challenge beckoned irresistibly to both Cooke brothers. “If successful,” Henry wrote back, “it would be the grandest achievement of our lives.” Cooke & Co. signed on as the Northern’s financial agent, with an undertaking to interest “the capitalists of Europe” in its securities. But Jay was planning to plunge deeper. He was about to irrevocably tie his and his firm’s future to the Northern Pacific Railroad.

TO SELL THE Northern’s bonds Cooke reached out again to Sam Wilkeson, who was marinating in the boredom of a New York publishing house, selling subscription works such as the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher’s Life of Christ to rubes. Receiving a letter from Cooke asking if he would like to “increase his income,” Wilkeson promptly replied, “You bet.” He snapped into action, writing articles describing in great detail the amenities of Duluth and the riches ready to be drawn from the fecund soil of Minnesota and the western territories, despite never having visited the region. The first issue of bonds sold out so quickly, Henry Cooke complained to his brother, that none remained for him to scatter to members of Congress as bribes.

Contemplating deeper involvement with the Northern Pacific, Cooke sought a firsthand report of the railroad’s prospects. In June 1869 he assembled an expedition to traverse the territory. Its members included Wilkeson; William Milnor Roberts, an engineer who had done work for Cooke in the past; Thomas Hawley Canfield, who had been an employee of the Northern dating back to the time of Josiah Perham; and R. Bethell Claxton, an Episcopalian minister whose Philadelphia church enjoyed Cooke’s lavish patronage and whose task was to assess the spiritual character of the peoples of the Far West.

Cooke assumed the travelers would return with a positive report. Among their other duties, they were instructed to gin up enthusiasm for the project among the residents of the distant region while they were in the field. Reaching Walla Walla, Washington Territory, they hired the largest hall in town to address the residents. Canfield took the podium first, to “a perfect storm of applause,” according to an account in the local newspaper. He attacked Congress “for the niggardliness of its grants, as compared with the great and valuable favors bestowed upon the central road [that is, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific], and assured the people that the line would be built in spite of opposition.” Claxton followed with a charming speech in which he declared that he had come West “expecting to see icebergs and polar bears in a land of perpetual snow,” but now felt bound to report back that he had come upon “a tropical paradise.”

Writing to Cooke, Wilkeson spared no hyperbole. From Puget Sound he reported that “salmon are not caught here, they are pitchforked out of the streams.” He added, “Jay, we have got the biggest thing on earth. Our enterprise is an inexhaustible gold mine.”

Wilkeson dispatched breathless accounts of the expedition’s findings to eastern newspapers, typically under pseudonyms. One article, published under the name “Carleton,” described for readers of the Boston Journal “a region . . . which comes nearer the Garden of Eden than any other portion of the earth. . . . gentle swells, parks, groves, lawns, lakes, ponds, pellucid streams—a rare combination of beauty and fertility. . . . Think of it, young men; you who are measuring off tape for young ladies, shut up in a store through the long and wearisome hours, barely earning your living. Throw down the yardstick and come out here if you would be men.”

Few voices were raised against the torrent of marketing bombast. One naysayer was General W. B. Hazen, a Union Army veteran stationed in the Dakota Territory. Hazen warned would-be settlers about depictions of the region as “one uninterrupted field of fruitfulness,” since “the interests of the railroad companies that it should be considered valuable land, are measured exactly by the number of millions of dollars for which it can be hypothecated.” Hazen described the land beyond the Hundredth Meridian, which bisected the Dakota Territory and the states of Nebraska and Kansas, as “altogether sterile . . . a dry, broken, and barren country, with very little timber and, from lack of moisture, unfit for agriculture.”

Skepticism was heard inside the Northern Pacific company, too. John Russell Young, a journalist who had worked on the government bond campaign with Wilkeson and had also come back onto the Cooke payroll, knew his colleague well enough to be wary of his claims. He told Cooke: “I hear that Sam has found orange groves and monkeys in his route.” Cooke would have been wise to heed Young’s implicit warning about Wilkeson’s flights of descriptive fancy, for thanks to the implausible publicity, the Northwest region soon became known as “Jay Cooke’s banana belt.”

While beating the bushes for homegrown American capital, Cooke dispatched his partner William G. Moorhead to Europe to sound out the Rothschild banking family about investing in the Northern Pacific. Moorhead reported back that he received a chilly reception from the Rothschild bank, which was still run by risk-averse elders. Cooke tried to strengthen his resolve by telling him, deceitfully, that the clamor for the bonds in America was thunderous—“I have hundreds of applications . . . I can get thousands to take hold at once. . . . I tell you I am busy night and day about this great matter.”

But Europe had had its fill of American railroad bonds, thanks to a surfeit of issues and to what Cooke’s partner Harris C. Fahnestock cautioned was “the bad odor” attached to other overpromised and underperforming Pacific railroads, including the Union Pacific.

Cooke dispatched a second mission under George B. Sargent, a former New York broker, who arrived in Europe in the spring of 1870 with letters of introduction from Baron von Gerolt, the Prussian ambassador to the United States, whom Cooke had wined and dined at Ogontz. By July 16, Sargent was on the verge of signing a deal with a British syndicate to sell $50 million of Northern Pacific bonds in the European market. The syndicate was to deposit the sum in gold to Cooke & Co.’s account three days hence. On July 19, however, France declared war on Prussia. With the start of the Franco-Prussian War, the European exchanges collapsed into panic and Sargent’s syndicate disappeared in a puff of smoke.

“I was stunned by the blow,” Cooke wrote later. French and Prussian investors “could no longer unite. . . . If rumors of war had kept off a week longer the papers would all have been signed.”

Cooke still found grounds for optimism. He sequestered Milnor Roberts at Ogontz to finish the report of the surveying expedition. As expected Roberts declared the railroad feasible, estimating that three years of construction would cost about $85 million. The project, he asserted, would benefit greatly from “emigration across the continent—the overflow of the redundant population of the Atlantic states and of Europe.”

Armed with Roberts’s say-so, Cooke announced the formation of a pool to raise the funds to launch construction of the Northern Pacific. Wilkeson wrote Cooke that upon hearing the announcement “I flung my hat to the ceiling.” The road “will plant civilization in the place of savagery,” he assured his patron, echoing Asa Whitney. “It will augment the national wealth beyond the dreams of the wildest economist.”

Cooke tried to guarantee himself a profit from the railroad by striking a hard bargain with the Northern Pacific’s Boston investors. The $100 million in loans he floated for the company carried a stiff interest rate of 7.3 percent, but of every $100 in face value, he kept a commission of $12 and advanced the railroad only $88. Experts who examined the deal with the hindsight of its ultimately dismal outcome detected the seeds of the Northern’s eventual downfall in its terms: “No extraordinary foresight was needed to see that a railroad could not be built through two thousand miles of absolute wilderness, and settle and develop the vacant country along its line fast enough to provide from its net earnings $7.30 interest per annum on $100 for every $88 expended upon it,” wrote the historian Eugene Smalley in 1883. “Bankruptcy was inevitable.”

Yet at first the railroad sailed atop a surging confidence in America’s manifest destiny. Cooke exploited this optimism for his sales campaign, along with a generous helping of graft. He distributed bonds among leading financiers, journalists, brokers, and politicians, including Vice President Schuyler Colfax. Wilkeson placed bonds in the hands of Horace Greeley and Henry Ward Beecher, the prominent abolitionist preacher whose works he had previously sold on subscription, “with some pleasing concessions to them as to the time and manner of paying their installments.” It was as if the Crédit Mobilier, in which Colfax had also invested, was again at large.

THE RAILROAD PROJECT did appear to deserve the hullabaloo, at first. Ground was broken on February 15, 1870. But this was mostly for public show, the ceremony being attended by more journalists than laborers. Anyone inspecting the photographs of the event had to notice that the dignitaries stood on a landscape encrusted in snow and that not a foot of the frozen earth had been broken by spades or pickaxes. The frigid weather meant that real construction could not begin for months; once it did, the crews immediately ran into marshy, boggy land and mosquitoes that attacked them in huge black clouds. From the start, embezzlement often left laborers without pay, food, or supplies.

Then there were the Indians. Asa Whitney’s confidence that the railroad would civilize the tribes was not shared by military men in Indian country. General Winfield Scott Hancock, a hero of Gettysburg now stationed in the Yellowstone valley of Montana, cautioned that pacifying the tribes would be difficult and expensive. “It is not seen that the construction of a railway into their country . . . will in any way tend immediately to diminish them,” he wrote Cooke, “but will most probably provoke their hostility . . . unless large subsidies be paid them to purchase peace. Our experience heretofore has not been favorable.”

Army soldiers escorted Cooke’s surveying teams as they made their way west toward the Yellowstone River. Through 1871 and the spring of 1872 the surveyors and their armed escorts worked largely unmolested, but they were jolted out of their complacency on August 14, 1872, when a surveying expedition on the Yellowstone was attacked by three hundred Indians under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, whose forces would prevail against US soldiers four years later at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. At the so-called Battle of Poker Flat the Indians were driven back at the cost of only a modest toll among the US soldiers, but the encounter sent an unnerving message back East, thanks to highly embellished accounts witnesses dispatched home to family members, which inevitably turned up in local newspapers. “Our force was wholly inadequate to pass down the Yellowstone Valley,” one surveyor wrote in a message published in the New York Times. “One morning the red rascals put four bullets into my tent, and four into my mess chest. . . . We held a council of war about two weeks later, and concluded to abandon the expedition.”

Cooke was learning, meanwhile, that American bankers had no more taste for Northern Pacific bonds than their European cousins. So much railroad capital was sloshing around Washington as graft that when Henry Cooke offered Northern Pacific securities to House Speaker James G. Blaine, who had emerged from the Crédit Mobilier scandal unscathed, Blaine responded by trying to foist bonds in a southern railroad scheme on him. (“Mr. Cooke resisted this pressing invitation,” reported Cooke’s official biographer, Ellis Oberholtzer.)

The Northern Pacific took heavy fire from newspapers hostile to Cooke, led by the Philadelphia Ledger, which was part-owned by Anthony Drexel, Cooke’s chief rival in Philadelphia’s financial community. The Ledger had been editorializing against congressional assistance to the Northern Pacific since 1869, at one point provoking an infuriated Cooke to write Drexel: “Do you think if I should start a newspaper, or rather own one, I would permit its editors and conductors to persistently and constantly misrepresent and injure the position of a neighbor and life-long friend?”

When a bill to provide the Northern with government financing was introduced in Congress in 1870, the Ledger intensified the attack. There had not been a time “since the celebrated South Sea Bubble when so much money was running into wild hazard,” the newspaper thundered. Cooke soon would have reason to suspect that Drexel was acting in concert with a new partner from New York: J. Pierpont Morgan.

Following the armistice ending the Franco-Prussian War in January 1871, Cooke made a third overture to European investors. In April he welcomed to Ogontz five Austrian and Dutch bankers intending to examine the route. After feting them at his estate he provided them with passage to Duluth by steamer under the leadership of Milnor Roberts. The delegates proved a sour bunch, most of their overheard remarks being “rather sneering,” Roberts advised Cooke. “They seem to have a notion that anyone they meet who praises anything has been hired to do it,” which may not have been far off the mark. Some of their reports upon returning home were so negative that Cooke suspected their authors’ purpose was to extort money from him to suppress them.

Meanwhile, construction progress was anything but auspicious. Cooke was not a corrupt operator like Gould, Fisk, or the architects of the Crédit Mobilier, but he was managing the Northern Pacific at long range and his representatives in the field were every bit as venal and incompetent as their counterparts on other roads. They tolerated millions of dollars in cost overruns, in part because much of the excess went into their own pockets. The Northern’s president, J. Gregory Smith, a former governor of Vermont who had been installed by the Boston group, handed out management posts to cronies—when he devoted any attention to the railroad at all. Incompetently built tracks were sinking into bogs and laborers were going unpaid. As early as 1870, William L. Banning, a shareholder from Minnesota who observed the progress of the Northern at close hand, had sounded the alarm: “I tell you, Mr. Cooke, what you want is so far as is possible to strip the Northern Pacific enterprise of all this slime.” But it was not until the summer of 1872 that Cooke forced Smith’s resignation.

By then, Cooke’s partners had become frankly dismayed. “The present actual condition of the Northern Pacific, if it were understood by the public, would be fatal to the negotiation of its securities,” Fahnestock told him in June. He warned that the railroad’s problems were sullying the reputation of the entire firm. “Radical and immediate changes are necessary to save the company from ingloriously breaking down within the next year and involving us in discredit, if not in ruin.”

TO MOST OUTSIDERS, Cooke & Co. seemed to be at high tide in 1872. As America’s preeminent financier, Cooke was sought after for charitable subscriptions of every kind. As a capstone, he was appointed chairman of Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition, which in 1876 would mark the nation’s one hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. An invitation to Ogontz was treasured as validation of a guest’s position in the highest echelon of politics or business. The reelection of President Grant, with whom the Cooke family’s relations were strong, seemed assured.

Behind the scenes, however, the Northern Pacific crisis was worsening. The railroad had borrowed more than $1.5 million from Cooke & Co. yet had virtually no prospect of raising the money to repay the loan—other than by borrowing more from Cooke. And Cooke’s chances of unloading Northern securities on investors at home or abroad were shrinking fast. Through the first half of 1873 money got tighter. That August the Ledger quoted, with evident glee, a correspondent’s report from Frankfurt that an American railroad bond would not sell in Europe “even if signed by an angel of Heaven.”

Cooke also came under attack from a new quarter. The battleground was the government’s plan to refinance $300 million in Civil War bonds at an interest rate reduced to 5 percent, a savings of a full percentage point. Cooke regarded the refunding, like the original Civil War debt, as his personal franchise. Not this time: Pierpont Morgan, in partnership with the financier Levi P. Morton and Anthony Drexel, and with backing from the British firm Baring Brothers & Co., was determined to shatter Cooke’s monopoly on the government business, a step on his campaign to take the Philadelphian’s place at the summit of American banking.

In January, Morgan and Drexel persuaded Treasury Secretary George Boutwell to split the $300 million refunding between their syndicate and Cooke. In financial terms the deal was not a coup for either camp, as the total commission to be divided between them was a paltry $150,000. But the bonds would not have to be delivered to buyers until the last day of 1873, which meant that if the securities could be sold promptly, the firms would have the use of the proceeds for most of the year—a lifeline, especially, for Jay Cooke & Co.

The bond issue turned out to be a fizzle. Contemporaries conjectured that Morgan deliberately slowed sales of the bonds to place pressure on Cooke, but that is implausible—Junius Morgan was unhappy that his son had participated in the financing without his permission, so it was hardly in Pierpont’s interest to make the venture look even more ill-advised. In any case, the bonds’ failure could be ascribed to a slump in general business conditions without having to adduce an ulterior motive on Pierpont’s part.

The developing economic weakness had several causes. One was the hangover of wartime production of crops and steel, which became overproduction as wartime demand evaporated—and intensified as farms and factories tried to preserve income in the face of falling prices. Farmers and railroad operators alike were heavily indebted, leaving them vulnerable to any tightening in interest rates. In the spring of 1873, financial panics swept through Berlin, Vienna, Paris, and London. The foundations of America’s economic expansion began to seem shaky. And that meant a loss of confidence in the main drivers of the expansion, the railroads.

By early September, faltering railroad investments were undermining investment firms all over the financial district. On September 8, the New York Warehouse and Security Co., which traded in commercial loans, declared itself insolvent; its president blamed its loans to “railways and . . . individual railroad builders.” Five days later, Kenyon, Cox & Co.—where Daniel Drew was a partner—shut down, having tried unsuccessfully to call in a $1.5 million loan to the Canada Southern Railroad. The contagion began to spread among other firms with outstanding loans to other crippled railroads, meaning almost all of them.

PANIC WAS EVIDENT in the New York markets on September 17. President Grant spent that night at Ogontz after dropping off his son Jesse at a nearby private academy. At breakfast the next morning, the president spied Cooke buried under a blizzard of telegrams from New York, though the sight gave him no hint of impending disaster. Grant left to board the train back to Washington and Cooke headed for his Philadelphia office.

The ax fell with sickening speed. In New York, Harris Fahnestock summoned bank presidents to his office and informed them that Jay Cooke & Co. was closing its doors. Cooke received a wire with the news before 11 A.M. and ordered the Philadelphia headquarters closed too. He turned his face away from his assistants as tears streamed from his eyes. No one in the office had ever seen him weep before.

But that was nothing compared with the reaction in the exchanges. The news hit Philadelphia “like a thunderclap in a clear sky,” reported the Philadelphia Press. The New York Stock Exchange was in an “uproar,” and a pall fell on every trader on the floor. On the sidewalks of Wall Street desperate depositors mixed with curious onlookers to gawk at staggering brokers like rubberneckers at an accident scene. Among the witnesses was George Templeton Strong, a lawyer whose daily entries in his personal journal would win him fame as a diarist. On September 18, the day after Cooke’s failure, he observed “one or two gentlemen who looked like they came from the country and who probably had monies on deposit with these collapsed bankers . . . walking about in an aimless sort of way and talking loud to nobody in particular about ‘d——d infernal swindlers and thieves.’” Two days later, Strong remarked that the stock exchange had closed its doors: “A wise measure, and would that they might never be reopened,” he wrote tartly. “The failure of these great stock-gambling concerns would be a public benefit but for its probable damage to so many honest businessmen.” (Trading would remain suspended for ten days.)

There was widespread consensus about where to place blame for the crisis: on the railroads, especially the Northern Pacific. Cornelius Vanderbilt leveled his judgment like a biblical prophet, lecturing the New York Herald as follows:

I’ll tell you what’s the matter. People undertake to do about four times as much business as they can legitimately undertake. . . . There are many worthless railroads started in this country without any means to carry them through. . . . Building railroads from nowhere to nowhere at public expense is not a legitimate undertaking. . . . Mistrust will be engendered till we, as a nation, do our business on a more solid basis, and pay as we go.

In the heat of the crisis, with institutions failing all around, many on Wall Street hoped that the Commodore would step in and rescue the market with his unlimited resources, even as he was about to enter his eighth decade. But it was a forlorn hope; Vanderbilt himself was strapped. The collapse had driven down shares of his three major holdings: the New York Central; the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, which ran between Chicago and Buffalo; and the telegraph company Western Union, by more than $50 million combined. The Union Trust Company, previously a reliable banking partner of the Vanderbilt railroads, called in a $1.75 million loan to the Lake Shore, which the road could not pay—threatening bankruptcy for the entire Vanderbilt empire and the Union Trust itself.

Pierpont Morgan surveyed the crash with relative equanimity from a vantage point safely removed from heavy exposure to the railroads, thanks largely to his foresight that a slump was coming and undercapitalized railroads would bring down their bankers. “The kinds of bonds which I want to be connected with are those which can be recommended without a shadow of doubt, and without the least subsequent anxiety, as to payment of interest,” he had written to his father as early as April 1873. He was wise to seek out the safest possible investments, for the aftermath of what came to be known as the Panic of 1873 would stretch far beyond that year.

UNTIL THE EVEN vaster economic calamity of the 1930s, the Panic of 1873 and its six-year aftermath would be what Americans meant when they referred to the “Great Depression.” It was a classic bubble, born of frenzied growth in the railroad industry that had long-term financial obligations but funded them with short-term debt and the issuance of grossly overvalued securities. The downturn, like its later cousin, would leave a lasting imprint on American industry, society, and politics.

The most immediate damage could be traced in the national accounts of profits, losses, and unemployment. The economy shrank by nearly a third from 1873 through 1879; bankruptcies doubled from fifty-one hundred in 1873 to more than ten thousand five years later. Virtually every sector of the economy was stricken. Wheat prices fell from $1.78 a bushel to $1.25. Bank failures rose from 3 in 1870 to 140 in 1878. Railroad construction ground almost to a halt. The industry had added a record 7,436 miles in 1872; three years later the construction boom was scraping bottom with only 1,606 new miles. It would not exceed the previous high-water mark until 1881.

The crisis exposed the incapacity of the government to manage the economic cycle. A few days after the stock exchange suspended trading, Grant made a pilgrimage to Wall Street with Treasury Secretary William A. Richardson, who had succeeded George Boutwell. They came to the Street as supplicants to bankers for a solution to the crisis, but the bankers themselves had no good ideas, beyond urging the government to buy in government bonds to pump inflationary funds into the economy.

The bankers’ fear was palpable: At the Fifth Avenue Hotel, where the president and secretary were staying, Harper’s Weekly reported, “the corridors and parlors swarmed with a multitude of frenzied people, who supposed that incalculable disaster impended and that the President had the power of staying it by a word, and of saving the country from financial, as he had saved it from political, ruin.” The mob included “speculators and gamblers in railroad stocks, . . . all passionately desiring that the President would use the public money for their relief.”

But Grant did not believe he could “establish a precedent of such momentous consequences” under the law. He ended up taking the half measure of allowing the release of $26 million in retired greenbacks—currency treated as legal tender but not backed by gold or silver, which had been issued during the Civil War and now was being bought in. This was a comparatively minuscule priming of the pump, for it amounted to less than a tenth of the greenbacks then in circulation; it was enough to help Wall Street past its immediate crisis, but did nothing to alleviate the pall enveloping the rest of the country. Unlike Franklin Roosevelt sixty years later, Grant would continue to resist inflationary measures, vetoing an “inflation bill” that would have drastically increased the money supply.

As the depression ground into its second year, Grant acknowledged in his annual message to Congress the “prostration in business and industries such as has not been witnessed with us for many years.” He recognized that “the greater part of the burden . . . falls upon the working man.” But he reiterated his uncompromising policy of “a return to specie payments, the first great requisite in a return to prosperity.” In other words, contracting the money supply to correspond to the supply of gold and silver. Grant’s policy was similar to that followed in 1932 by Herbert Hoover, who insisted on keeping America yoked to the gold standard in the face of economic disaster. It would have a similar result politically—in Grant’s case, a drubbing suffered by his Republican Party at the midterm election in 1874.

The Panic of 1873 sharpened the divide in America between the working class and its increasingly corporatized employers. The depression that followed also dramatically changed the internal dynamics of the railroad industry and the relationship between the roads and their workers. Prior to 1873 the roads existed in a sort of paradise of serene mutual cooperation, with “official” rates based on the value of freight and adhered to generally, despite secret or even overt rebates here or there. Railroad employment was strong, and an entire cadre of workers entered the industry with the expectation of long-term employment. During the depression, these informal harmonies came to an end. “With the increasingly desperate search for traffic, rate agreement collapsed,” observed the business historian Alfred Chandler. Competition among large, sprawling, powerful enterprises—especially those with high fixed costs to cover—was a new phenomenon in American business. By 1876, cutthroat competition for diminishing traffic would send more than half of America’s railroads into bankruptcy, their workers cast into the cold.

Before then, the wealthy Americans who had contributed to the crash had launched themselves upon an era of unprecedented conspicuous consumption. The action driving The Gilded Age, the acerbic 1873 novel by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, was its characters’ efforts to seek their fortunes in railroad speculation. But the title soon came to signify more generally the ostentation and amorality of the “robber barons,” to use the label first applied in the United States to Cornelius Vanderbilt by the German-born political reformer Carl Schurz. In popular usage, that label itself broadened to signify all the railroad, steel, and banking magnates who were thought to control the nation’s wealth, with the “insinuation that pernicious conduct was typical of all big businessmen.”

These new aristocrats increasingly settled in New York. By the end of the 1870s, reckoned the stock trader and social observer Henry Clews, the city had “more wealth than thirteen of the States and Territories combined. . . . The great metropolis attracts by its restless activity, its feverish enterprise, . . . its imperial wealth, its Parisian, indeed almost Sybaritic luxury, and its social splendor. It is really the great social center of the Republic, and its position as such is becoming more and more assured.”

In New York, the frenzy of conspicuous spending fed on itself, slowed only temporarily by financial panics such as that of 1873. The colonization of a few blocks of Manhattan facilitated the trading of suspect railroad paper; the financiers were all neighbors who could pop into each others’ homes of an evening to execute their deals or accomplish their mutual betrayals out of the eyesight of the public and their small investors. Proximity also facilitated the contest of ostentation. The robber barons competed to build the biggest mansions and throw the most lavish parties. According to the gossipy boulevardier Ward McAllister, who assiduously chronicled the era’s excesses (and had coined the term “the Four Hundred” for the crème de la crème of nouveau riche society, supposedly to denote the largest crowd that could be accommodated in Caroline Astor’s ballroom), the premier venue for these events was Delmonico’s on Fourteenth Street, which was “admirably adapted” for balls of seven or eight hundred guests. “Certainly one could not have found better rooms for such a purpose” in this “era of great extravagance and expenditure,” McAllister reported in his book Society As I Have Found It (issued in a deluxe edition limited, somewhat mischievously, to four hundred copies).

The new tycoons had not only established New York as the social and financial center of the nation, but established the railroads as the focus of banking and finance. Railroad “financiering,” which was not at first considered a salubrious practice, became a profession—indeed, for many investment houses the principal source of income.

Few contemporaries judged the industrial princes of the era to be paragons of cultural sophistication. Charles Francis Adams left an especially acerbic assessment. “Money-getting,” he wrote in his autobiography,

comes from a rather low instinct. Certainly, so far as my observation goes, it is rarely met with in combination with the finer or more interesting traits of character. I have known, and known tolerably well, a good many “successful” men—“big” financially . . . and a less interesting crowd I do not care to encounter. Not one that I have ever known . . . is associated in my mind with the idea of humor, thought or refinement. A set of mere money-getters and traders, they were essentially unattractive and uninteresting.

Writing just two years before the end of his life, he counted himself lucky to have survived his encounters with this stratum of society free of contamination.

THE HAVOC WREAKED throughout the American economy by the Panic of 1873 would not fully dissipate until the end of the decade. The pace of bankruptcies did not peak until 1878, when businesses worth more than a quarter-billion dollars went under. Farm debt was driven ever higher by a collapse in crop prices, giving rise to a movement for the inflationary coinage of silver that would roil American politics virtually to the end of the century.

The panic also profoundly affected the fortunes of some of America’s leading tycoons. Vanderbilt survived the carnage, but in a temporarily humbled state. His near failure inspired him to reorganize his empire into a more integrated and manageable system, which would continue past his death in 1877 as one of the major railroad networks in the country.

Jay Cooke was virtually wiped out, never to regain his position at the summit of financial affairs during the final three decades of his life. Cooke’s departure from the scene left the future open for Pierpont Morgan. Having detected signs of economic weakness in advance, Morgan had strengthened his firm’s financial position sufficiently to ride out the storm, though he was shaken by the collapses around him. Not yet having reached a position where he could take direct part in resolving the panic, he drew from it the lesson that when the government’s ability to address serious downturns came into question, it would be up to responsible individuals to step in. Come the next major panic, in 1893, he would take on that role.

The one notable survivor of the panic was Jay Gould, who was able to pick over the wreckage for bargains during the long aftermath. In the next few years he would accumulate railroad lines across the Midwest, the Western Union Telegraph Company, and what may have been the grandest prize of all: the Union Pacific.