A view of Wellington in summer, around 1910, with the avalanche slope visible straight ahead. Established in the early 1890s, when the Great Northern first built its line through the wilds of the Cascade Mountains, the town existed solely to serve trains coming through the Cascade Tunnel on their way to and from Seattle. (Courtesy of the Museum of History & Industry, Seattle)

James H. O’Neill, superintendent of the Great Northern’s Cascade Division, in 1910. A railroader through and through, he had begun his career as a thirteen-year-old water boy and had since worked his way up through the ranks. At the time of this photo, he was thirty-seven years old and in charge of all GN operations in the western half of Washington State. He was directly responsible for the fate of the two trains stranded at Wellington. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Curtis17474)

O’Neill, in white shirt and vest, as a water boy with a railroad work gang in the Dakota Territory, circa 1886. (Courtesy of Jeanne Patricia May)

BELOW LEFT: O’Neill as a youth. In order for the underaged boy to work as a brakeman, his parents had to formally indemnify the railroad of all liability in case of accident. (Courtesy of Jeanne Patricia May)

BELOW RIGHT: Berenice McKnight, whom O’Neill married in October 1908. A gifted painter and pianist from a prominent Montana family, Berenice was better educated, better connected, and fourteen years younger than her husband, but their marriage was one of unusual closeness. (Courtesy of Jeanne Patricia May)

The Great Northern’s founder and chairman, James J. Hill, was called the Empire Builder of the Northwest. Often regarded as the last of the great railroad barons, the irascible, indomitable Hill had taken a small, bankrupt Minnesota railway line and turned it into one of the premier railroad empires in the country. (Courtesy of the James J. Hill Reference Library, Louis W. Hill Papers)

A rotary snowplow and its crew. Pushed by one or two trailing locomotives, rotaries were the state-of-the-art snow-fighting machines of their day. Under normal winter conditions, a fleet of six could usually keep even the GN’s notoriously snowy Cascade crossing open to traffic. (J. D. Wheeler Photograph, courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection)

A rotary on the job in Tumwater Canyon, east of the Cascade Tunnel. Work gangs accompanying the plow would often have to shovel snow by hand down to a depth of thirteen feet, the maximum that the plow’s rotating blades could handle. (Courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection)

Edward “Ned” Topping, a traveling salesman for an Ohio-based hardware manufacturer, was a passenger aboard the ill-fated Seattle Express. Still mourning the recent deaths of his wife and unborn daughter, he was writing a day-by-day account of the Wellington crisis for his mother. The letter was found in the wreckage of the train after the avalanche. (Courtesy of John Topping)

Alfred B. Hensel, known as “A.B.” to family and friends, was one of the mail clerks on the trapped Fast Mail train. On the early morning of March 1, shortly before the avalanche, he moved his bedding from one end of the second-class mail car to the other to find a more comfortable sleeping place. As a result, he was the only mail clerk to survive. (Courtesy of Dolores Hensel Yates)

“Dead Man’s Slide,” with the Scenic Hot Springs Hotel visible below. In the two days before the avalanche, several groups of passengers and railroaders escaped by sliding—at great risk to themselves—from the upper rail line to the hotel. Later, the dead and some of the injured were evacuated from Wellington down this slope. (Courtesy of John Topping and the Robert Kelly Collection)

The Hotel Bailets (a.k.a. Bailets Hotel), where the passengers ate their meals while stranded at Wellington. Although its location was considered more vulnerable to avalanches than that of the passing tracks on which the trains stood, the hotel was left undamaged by the slide. (Note: The words “Hotel Bailets” on the roof were physically added to the photograph.) (Courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection)

Wellington, just after the avalanche. The overhead catenary wires, badly damaged in the slide, were what powered Wellington’s four GE electric locomotives. The smokeless “electrics” could pull trains through the Cascade Tunnel without the asphyxiation danger created by the polluting steam engines. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Curtisl7481-1)

Superintendent O’Neill inspects the wreckage of a railroad car at the avalanche scene. Many of the cars were deeply buried, but the remnants of a few lay near the surface, scattered over acres and acres of steep, treacherous terrain. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Curtisl7469)

Workers among the wreckage. Rescue and recovery efforts were complicated by the vast amount of timber and other debris brought down by the avalanche. At times, rescuers had to dive into the wreckage to pull victims out “as if taking them from a river.” (PHOTOGRAPH ABOVE: J. D. Wheeler Photograph, courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection; PHOTOGRAPH BELOW: J. A.Juleen Photograph, courtesy of the Everett Public Library)

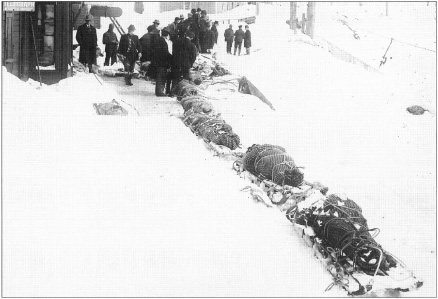

Avalanche fatalities lying in the snow. Once recovered and—if possible—identified, the bodies of the dead were wrapped in brown-and-white checked GN blankets and lined up to await removal. (Courtesy of the Museum of History & Industry, Seattle)

Tied to rugged Alaskan sleds, bodies were evacuated down the right-of-way in groups of a dozen at a time. Each sled was maneuvered by four men with ropes, two ahead and two behind. Once they reached the top of Dead Man’s Slide near Windy Point, they were lowered by rope to a train waiting at Scenic below. (J. D. Wheeler Photograph, courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection)

Some injured survivors were able to hike down to Scenic. Here, several injured men, their heads heavily bandaged, emerge from a nearly buried snow shed, led by rescuers and what appear to be newspapermen. The figure near the center of the group (with crooked arm holding a walking stick) may be Superintendent O’Neill. (Courtesy of the Jerry Quinn Collection)

A view looking northeast from the avalanche track back to Wellington, showing how the depot (center) and the hotel (left) narrowly escaped destruction. The wrecked structure to the west of the depot is probably part of an electrician’s cabin. (J. A.Juleen Photograph, courtesy of the Everett Public Library)

Several of the injured survivors, along with their nurses and assorted Wellington residents, gather for a group portrait outside the enginemen’s bunkhouse, which served as a makeshift hospital after the avalanche. (Courtesy of the Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center)

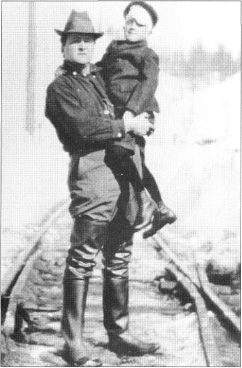

Dr. A. W. Stockwell, the physician in charge of the bunkhouse hospital, holds seven-year-old Raymond Starrett. When pulled from the wreckage, the boy had a thirty-inch wood splinter lodged in the skin of his forehead. Since Dr. Stockwell was not yet present on the night of the avalanche, Wellington telegrapher Basil Sherlock removed the splinter with a shaving razor. (Courtesy of the Wenatchee Valley Museum & Cultural Center)

The first through train reached Wellington on March 12, eleven days after the avalanche. Another slide early the next morning toppled a rotary off the mountain, killing a workman and closing the line yet again. Regular traffic did not resume until March 15. (J. D. Wheeler Photograph, courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection)

The Wellington passing tracks after being cleared by a rotary plow. The height of the walls on either side gives some indication of the sheer volume of snow that had to be removed to open the line. (J. D. Wheeler Photograph, courtesy of the Robert Kelly Collection)

Salvage efforts went on for months after the avalanche. Most of the wooden train cars were totally annihilated (“as if an elephant had stepped on a cigar box,” as one witness put it), but the much heavier locomotives suffered surprisingly little damage. (Courtesy of the Jerry Quinn Collection)

An older James H. O’Neill (second from left) joins other officials for the opening of the GN’s New Cascade Tunnel on January 12, 1929. This much lower tunnel enabled the Great Northern to eliminate miles and miles of steep, avalanche-prone track between Berne in the east and Scenic in the west. Stations like Wellington (renamed “Tye” after the disaster) and the old Cascade Tunnel Station were dismantled and allowed to return to their natural state. (Courtesy of the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Pickett4203)

The abandoned Wellington site, circa 1930, with only the depot and the concrete snow shed (built after the slide) remaining to mark the spot. Today, the depot is long gone and the site is deeply forested once again. The concrete snow shed remains, a fitting monument to the Wellington dead. (Courtesy of Warren Wing and the Robert Kelly Collection)