The Winter’s storm of Civil War I sing

Whose end is crowned with eternal Spring,

Where Roses joined, their colours mix into one,

And armies fight no more for England’s Throne

Bosworth Field, Sir John Beaumont

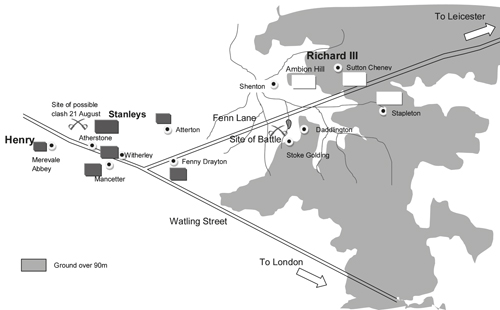

Dawn came at 5 a.m. on 22 August, but before setting out Henry sent Sir Reginald Bray to meet with Thomas Stanley again, asking him to take command of his van; Stanley refused. According to Vergil he told Henry that ‘the Earl should set his own forces in order while he would come with his array well appointed’. Vergil continues, saying that it was not what Henry wanted to hear and ‘to that which the oportunytie of time and weight of cause requyryd, thowghe Henry wer no lyttle vexyd, and began to be soomwhat appallyd, yeat withowt lingering he of necessytie orderyd his men in this sort’. According to the The Ballad of Bosworth Field, Stanley then lent Henry four of his best knights: Sir Robert Tunstall, Sir John Savage, Sir Hugh Persall and Sir Humphrey Stanley, along with their retinues. However, we have a variation in accounts here, as Vergil says that Savage had joined the Tudor army the previous day. Beaumont says in his poem, Bosworth Field, that the Stanley camp was also visited by Brackenbury and that he commanded the Stanleys to join Richard’s army or else Lord Strange would be executed. Thomas Stanley replied that, after the death of Hastings, they did not trust Richard and that he had plenty more sons if Lord Strange was executed. Knowing that he had the support of the Stanleys, Henry then probably gathered his army at Witherley, as it was here that Henry knighted his standard bearer William Brandon and several other followers, no doubt to boost morale.

STANDARD BEARERS

The standard was the rallying point in medieval battles and identified the location of the king. The standard bearer therefore had to remain close to the king at all times and the position was considered a great honour bestowed upon one of the king’s strongest and best fighters.

Richard, on the other hand, did not have a good start to the day. When he rose, he looked paler and more drawn than usual. Both Vergil and the Crowland Chronicle say he told his followers that he had a bad night, his dreams plagued by visions of evil spirits or demons, which Vergil ascribes to a guilty conscience. The Crowland Chronicle also adds that his chaplains were not ready to celebrate Mass nor was his breakfast ready, quite possibly because he was up earlier than expected. Richard may have had his faults, but he was unquestionably pious and would not have missed Mass. Tradition has it that he actually took his last Mass at nearby Sutton Cheney church, which even today still drips with Ricardian symbolism. If Edward Hall’s chronicle is to be believed, Norfolk was given a warning of what would happen that day, for when he woke he found a note pinned to his tent that said:

Jack of Norfolke be not to bolde,

For Dykon thy maister is bought and solde.

Richard must have known that Henry was gathering his army. As Richard gathered his men, it was reported in the Crowland Chronicle that he told his followers that:

… to whichever side the victory was granted, would be the utter destruction of the kingdom of England. He declared that it was his intention, if he proved the victor, to crush all the traitors on the opposing side; and at the same time he predicted that his adversary would do the same to the supporters of his party, if victory should fall to him.

Another tradition is that he also drank from a spring at the foot of Ambion Hill before he set out, now called ‘King Richard’s Well’.

The majority of the chroniclers agree that some, if not all, of Henry’s army had the sun behind them during the battle. As they were coming from the west, it means that it must have been fought, at least in part, during the afternoon, although we do not know what happened during the rest of the morning. Henry’s troops probably took a while to assemble but, having learned of Richard’s location, then advanced along Fenn Lane towards him. Encumbered by artillery and all the equipment of war, progress would have been slow. We are told that Henry had local guides, and although both John Cheyne and Robert Harcourt were local, we also hear of John de Hardwick from Lindley and a commissioner of array for Leicestershire showing them the way. The Stanleys, on the other hand, probably started out earlier, were travelling lighter and therefore would have moved far quicker.

We now know that Richard’s army moved away from Ambion Hill and to get to the site of the battle they either had to move directly south towards Fenn Lane or more likely west to Shenton, and then follow the route south to Fenn Lane. A local tradition is that Henry was encamped at Whitemoors, which is just north of the battlefield and along this lane. This was probably due to finds associated with the battle during the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries but, given that it was believed that the battle was fought to the east on Ambion Hill, it would have been an easy assumption that it was Henry’s camp. However, there could be a small grain of truth in this rumour, for if Richard had taken this route south, then it would be a likely spot to leave his baggage train before the battle. Why he would have taken this route or even come down off the high ground is unknown, because by going back along the ridge towards Sutton Cheney he would have retained the tactical advantage of the high ground. Perhaps he could already see troops massing there?

Initial movements

39. Sutton Cheney church, where Richard traditionally took part in his last Mass. (Richard III Foundation inc.)

It is possible that Richard’s army was taken by surprise, for a manuscript written around 1554 by Lord Morley cites a report by Sir Ralph Bigot that said the royal chaplains were unable to perform Mass before the battle because of a lack of organisation. Bigot was present at the battle and as knight of the body to Richard and master of his ordinance, ranked highly in his household. He would also go on to serve in Henry’s mother, the Countess of Richmond’s household. Some form of religious service was expected before a battle and a processional crucifix was found near Sutton Cheney during the eighteenth century. So if this report is accurate, then only an unexpected and threatening situation could have caused the resulting confusion in Richard’s ranks. Another version of events can be found in The Ballad of Bosworth Field, which describes Richard taking an oath in the name of Jesus and swearing to fight the Turks before his assembled army in true crusader style. Of course, any man undertaking a crusade would be offered remission for any and all previous sins, and by doing this Richard would have hoped to cleanse his past.

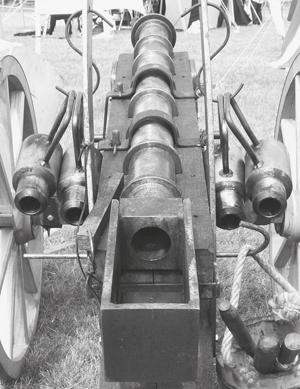

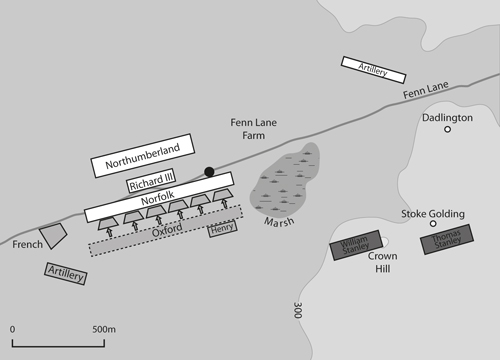

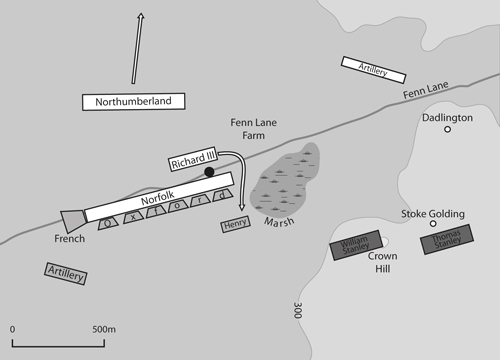

The area where the two sides met was centred on Fenn Lane, the Roman road to Leicester, and 3.6km (2.25 miles) north of the major Roman road of Watling Street. It was also at the junction of the boundaries of the medieval villages of Daddlington, Stoke Golding, Upton and Shenton, and 3km (1.86 miles) south-west of Ambion Hill. The ground was a flat plain, mainly comprising fenland crossed by streams, with an area of peat marsh, known as Fen Hole, south of the road. South of this marsh, the ground gently rises 20m (65ft) to a ridge that overlooks the road. On the top of the ridge is the village of Stoke Golding and approximately 600m (650yd) further north-east is the village of Daddlington. The ridge continues north-east towards Sutton Cheney, with a westerly facing spur now known as Ambion Hill creating a shallow valley enclosed on three sides, before falling 30m (98ft) back into the plain and the battlefield itself.

In working out the most likely way the sides deployed, we must first examine the sources. We hear from Polydore Vergil that:

There was a marsh betwixt both hosts, which Henry of purpose left on the right hand, that it might serve his men instead of a fortress, by the doing thereof also he left the sun upon his back.

40. Looking towards the area on the battlefield where the boar was found. (Ian Post)

The find of the gilt boar on the edge of the marsh, found during the recent archaeological investigation, and Vergil’s statement confirm the location of Henry’s right flank. It also appears from Vergil’s information that they were facing east and deployed north to south, at right angles to the Roman road, with the sun behind them. However, the recent archaeological survey has found a line of battlefield debris including a broken sword hilt almost parallel to the road, which suggests the battle, and therefore Henry’s line, was west to east. This makes little sense until it is combined with two other sources. Firstly, Jean Molinet says that the French were not part of the main army and that:

The French also made their preparations marching against the English, being in the field a quarter league away … knowing by the king’s shot the lie of the land and the order of his battle, resolved, in order to avoid the fire, to mass their troops against the flank rather than the front of the king’s battle.

Then there is also a stanza in The Ballad of Bosworth Field that says:

Then the blew bore [Oxford] the vanguard had;

He was both warry and wise of witt;

The right hand of them [the enemy] he took;

The sunn and wind of them to gett.

This is also supported in another ballad The Rose of England, which says Oxford made a flank attack, a common tactic at the time. So, if the ballad’s ‘vanguard’ is the main body of the French, then it was these who had the sun behind them, and the east/west battle line then makes perfect sense.

41. Looking west across Henry’s position. (Ian Post)

Why did they deploy parallel to the road and not across it? For any part of Henry’s army to have the sun behind them then part, if not all, of the battle had to have been fought in the afternoon. Richard may not have wanted to give Henry the advantage of the sun and arranged his army accordingly. However, it is much more likely that something, or someone, had forced Richard to deploy parallel to the road. This was most probably the Stanleys, who having arrived first had already assumed a blocking position on the rising ground overlooking the road, with whoever controlling the high ground taking a distinct advantage. The Ballad of Bosworth Field tells us that the Stanleys withdrew to a mountain where they looked across the plain and could not see the ground for men and horses. In medieval times, any high ground was called a mountain and the only high ground at Bosworth was where the land rises towards Stoke Golding, behind and to the left of Henry’s army. This becomes significant when in another part of the ballad we hear that, as the two sides came together:

King Richard looked on the mountaines hye,

& sayd, ‘I see the banner of the Lord Stanley’.

He said, ‘feitch hither the Lord Strange to me,

for doubtlesse hee shall dye this day’.

42. Looking east across the battlefield towards Stoke Golding and Crown Hill. (Ian Post)

Richard would only have wanted to execute Strange if he saw the Stanleys as an immediate threat, and what bigger threat could they have posed than being positioned behind Henry’s army. Whilst the Crowland Chronicle does not say where the Stanleys were exactly, it does say that Richard ordered Strange’s execution as the two sides approached each other. Another of those local traditions says that marks in the windowsill of Stoke Golding church were made by men sharpening their weapons. Could these be from Stanley’s men as they prepared for battle? So if we position William Stanley in the area around Crown Hill and Thomas further east near Stoke Golding, or behind his brother, together they could have blocked Richard’s army from moving towards Watling Street or threatened his flank if moving west along Fenn Lane. If this is the case and they were in position before Richard arrived, then Richard would have had no alternative but to form up in front of the Stanleys, parallel to the road. It could be that it is this position to which Vergil refers when he says ‘… Thomas Stanley, who was now approchyd the place of fight, as in the mydde way betwixt the two battaylles, that he wold coom to with his forces, to sett the soldiers in array’, because it would have been close to halfway between the two armies before they set out. With Henry’s main army approaching from the west and the Stanley’s in front of him, Richard had been caught in a trap. Was this what the anonymous author of the note received by Norfolk was hinting at?

First phase

43. Looking west across the battlefield, where Richard was initially deployed. (Ian Post)

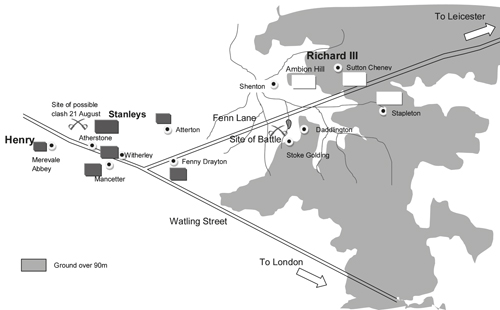

We must now turn our attention to the artillery. The Ballad of Bosworth Field hints at Richard’s deployment of his guns:

They had 7 score Serpentines without dout,

that locked & Chained uppon a row,

as many bombards that were stout;

like blasts of thunder they did blow.

The chaining of the guns together in the centre of the line would have certainly hampered any movement by the infantry, but if placed on the flank, in enfilade, they could rake Henry’s lines with cannon fire and cause maximum destruction to his ranks. They would also create an effective barrier, protecting the flank against attack. Additionally, they would also potentially be in danger of being dragged off by Oxford’s men during the battle, so it would make sense to chain them together. There is also some physical evidence to support this theory, as small groups of cannonballs were found close to the road, just where you would expect the guns to be positioned.

44. One of the lead cannonballs in situ on the battlefield. (Author’s collection)

As Henry had fewer guns, it makes sense that he would have placed them as far as possible from the enemy gun line and on the left flank, as this would have helped to protect it without hampering troop movement. Having established the approximate positions of the battle lines, we can then estimate the position of the opposing forces’ artillery by examining the pattern of cannonballs. The natural target for the guns would be the centre of the enemy’s line, so with this in mind fields of fire emanating from Richard’s and Henry’s left flanks can be traced. In both cases, this would place them close to the roads and, as guns were heavy and difficult to move across country, this would be an obvious place to find them. This also is supported by Molinet’s comment about the French attack on Richard’s right flank, which would have been out of sight of the guns and their line of fire.

45. A modern reconstruction of a fifteenth-century cannon. The separate breech (hanging inside the wheels) is fitted into the square block in the foreground. Wooden blocks hammered into place ensure a tight fit. (Author’s collection)

As to who was where, Molinet tells us that:

King Richard prepared his ‘battles’, where there was a vanguard and a rearguard; he had around 60,000 combatants and a great number of cannons. The leader of the vanguard was Lord John Howard [Norfolk] … Another lord, Brackenbury, captain of the Tower of London, was also in command of the van, which had 11,000 or 12,000 men altogether.

We therefore have Norfolk in command of the first line, probably with his son Thomas, Earl of Surrey, and Lord Brackenbury. Thomas had served a two-year military apprenticeship in Burgundy under Charles the Bold from 1466 to 1468 at the request of Edward IV, before fighting beside him at Barnet. It must have been an impressive sight as Vergil describes the vanguard as:

… stretching yt furth of a woonderfull lenght, so full replenyshyd both with foote men and horsemen that to the beholders afar of yt gave a terror for the multitude, and in the front wer placyd his archers, lyke a most strong trenche and bulwark.

Like the Battle of Towton twenty-four years earlier, it appears that all the archers were brought to the front, including Richard’s yeoman archers. Only mentioned in passing was a number of hand-gunners, who were probably Burgundians under the command of Salaçar; they would have been deployed in the first line or on the flanks, and may have been in blocks or dispersed throughout the archers. When Vergil refers to horsemen it is not clear whether he means mounted or dismounted knights, although we know that knights usually fought on foot at this time and the action that follows does not sound like a cavalry action. If they were mounted, it was usual for them to be on the wings, and although Oxford’s right wing was protected by the marsh, a short, sharp cavalry charge against the left would have devastated his line. An experienced commander like Richard would not have missed this opportunity unless something was stopping him: Henry’s artillery. With both of Henry’s flanks protected, negating any cavalry action, fighting on foot was the only option left for Richard’s fully armoured knights.

To the rear of the vanguard was Richard and ‘a choice force of soldiers’, which would have included his bodyguard, household troops and personal retainers. Behind them was the Earl of Northumberland with what the Crowland Chronicle describes as a large company of reasonably good men. If Norfolk had all the archers and best infantry in the first line, and Richard was in the second line with his household, then Northumberland probably commanded the troops raised by commissions of array. These were, as previously described, raw recruits and would have had little or no experience of war. Vergil suggests that many would have changed sides or fled before the battle had begun had Richard’s scurries not prevented them from doing so. Richard’s array was therefore textbook Vegetius, with three battles one behind the other, used many times before in England and Europe. A number of historians have suggested that Richard’s three battles were in a line, side by side, with Northumberland on the right. It has also been suggested that the reason that Northumberland did not get involved is because he was pinned in place by the Stanleys. Neither is likely, because firstly we are told that Richard has to move past both vanguards to get to Henry; we have already seen that the vanguard contained both archers and foot, and there is no mention of him passing Northumberland. Secondly, we are told that Northumberland should have charged the French, which would have been impossible if he was on the right flank.

Once Richard had formed up in battle array, Henry’s army was free to form up in front of them. With such a long line facing him, Henry would have had no alternative but to match Richard’s deployment, or face the risk of being enveloped as the longer line wrapped itself around the sides. We are told by Vergil that Henry:

… made a sclender vanward for the smaule number of his people; before the same he placyd archers, of whom he made captane John erle of Oxfoord; in the right wing of the vanward he placyd Gilbert Talbot to defend the same; in the left verily he sat John Savage.

As we have seen, the French were likely in a separate formation to the side or behind Henry’s left flank. Henry was somewhere to the right of his line, probably behind the marsh, as Beaumont reports that he was in the shadow of the hill. With him was his personal retinue, which perhaps included his uncle Jasper, Sir John Byron, Sir Walter Hungerford and possibly a unit of French pikemen and cavalry. We are not told where Alexander Bruce and his Scots cavalry or the Scots infantry under John of Haddington were positioned; however, it is possible that the infantry were with the French considering the commonality of weapons and fighting methods.

The Ballad of Bosworth Field does confuse the issue when it says:

theyr armor glittered as any gleed;

in 4 strong battells they cold fforth bring;

they seemed noble men att need

as euer came to maintaine [a] King.

The most likely explanation for this is that the author is referring to Henry’s army and the four ‘battles’ are Oxford’s, the French and the two Stanleys’. This then supports the theory that the French were separate and that the Stanleys had already declared their allegiance to Henry. It was a common Swiss and French tactic to form up in four ‘battles’, in echelon (obliquely), and was successfully employed by the Swiss at the Battle of Morat nine years earlier. Richard may have had the larger army, but Henry already had two advantages: his right flank was protected by the marsh, and he was on the higher ground. Both limited the effects of Richard’s superior artillery, for, as we have seen, a cannon’s maximum range was attained through the ball bouncing over firm ground, and cannonballs do not bounce well in marsh or uphill.

We do not know how many men faced each other that day, as medieval chroniclers always appear to be wildly inaccurate when estimating how many men fought in a battle. Molinet puts Richard’s army as having 60,000 men and The Ballad of Bosworth Field says 40,000. Only Vergil gives the size of Henry’s army, which he puts at 5,000 men, and comments that Richard had at least twice as many.

The confused Castilian Report says that Richard’s vanguard had both 7,000 and 10,000 men at different points, and Molinet says it was 11,000 or 12,000. The length of the line of battlefield debris found during the recent investigations is around 914m (1,000yd), so the two vanguards must have been at least this long. Assuming that there were no gaps in the vanguards and that men require a metre of space each when fighting side by side, then we can estimate that there were around 1,000 men in the front line of the two vanguards. Norfolk would also have had at least two or three ranks of archers and at least three ranks of infantry and knights, so there must have been a minimum total of 5,000 men in the vanguard. However, the vanguard could easily have been ten ranks deep given that the royal yeoman archers alone had raised 3,000 men in the past, meaning that 10,000 men is not outside the realms of possibility. Not one source gives the number of men in Richard’s ‘battle’, but in all probability it was comparatively small as the majority of his archers were in the vanguard. Only Molinet gives a total of 10,000 men under Northumberland, although this is probably an exaggeration. We can therefore estimate that Richard’s army had between 10,000 and 15,000 men in total.

We are told that Henry’s vanguard was slender, but that it also matched Norfolk’s in length. It is unlikely that the men were deployed less than three or four men deep, or 3,000–4,000 men, as a line only two men deep would be quickly overrun by the superior numbers of Richard’s forces. With the French in their separate formation and consisting of approximately 1,000 men, Vergil’s estimation of 5,000 men could be close to the truth. Sources vary widely as to the size of Stanley’s force, with de Commines saying that Stanley brought Henry 26,000 men, whilst Vergil estimated William Stanley’s forces at 3,000 men.

46. The battle started with an archery duel. (Author’s collection)

A number of historians have described the battle as a clash between the old style of warfare, espoused by Richard, and the new style of warfare learnt by Henry during his time on the Continent. It is also believed that Richard did not know how to respond to Henry’s tactics, although given that many of Richard’s men had been fighting on the Continent and that Salaçar was newly arrived from Europe, this was almost certainly not the case.

Henry must have advanced on Richard first, as the Crowland Chronicle says that ‘the earl of Richmond with his men proceeded directly against King Richard’. No doubt Richard’s artillery opened fire as soon as they were in range and Norfolk’s archers would have followed suit. With the likely amount of firepower arrayed against them, Henry’s men had no alternative but to advance or else be destroyed where they stood. Then, when Richard saw Henry’s army passing the marsh:

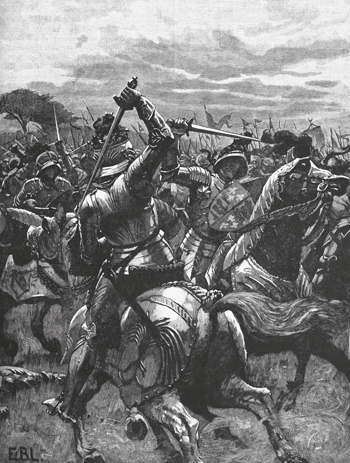

… he commandyd his soldiers to geave charge uppon them. They making suddanely great showtes assaultyd the enemy first with arrowes, who wer nothing faynt unto the fyght but began also to shoote fearcely; but whan they cam to hand strokes the matter than was delt with blades.

Norfolk’s and Henry’s archers exchanged fire as they charged to meet each other, before grasping their bucklers and drawing their swords ready for the hand-to-hand fighting to come. Medieval warfare was bloody and brutal, and with a resounding crash the two sides met: swords slashing, bills and halberds chopping and stabbing, arrows flying through the air as archers continued to take potshots at the mass of men. The fully armoured knights and their retinues followed behind, carving their way through the lightly armoured men with sword or pollaxe, looking for equals. Small groups of lightly armoured men isolated and pinned down heavily armoured opponents looking for chinks in their armour so they could deliver the coup de grâce. The noise must have been deafening as metal clashed with metal, mingled with shouts and cries, and the roar of cannon and hand-gun; the whole scene shrouded in a fog of gunpowder smoke.

Second phase

The two sides then disengaged, although why they did this is not clear. Perhaps, as modern research suggests was necessary for all medieval battles, both sides paused for breath and regrouped under their lords’ standards. It may have been because Oxford’s division was being beaten and he was in fear of being enveloped, as Vergil tells us:

... fearing lest hys men in fyghting might be envyronyd of the multitude, commandyd in every rang that no soldiers should go above tenfoote from the standerds … with the bandes of men closse one to an other, gave freshe charge uppon thenemy, and in array tryangle vehemently renewyd the conflict.

DEATH ON THE BATTLEFIELD

Although many would have died on the battlefield from horrifying wounds and loss of blood, many more would have died in the days that followed from blood poisoning and gangrene. One of the main causes of this was from arrows, which had been planted in the ground beside an archer. The archer would then go to the toilet where he stood, adding to the bacteria and germs in the ground.

47. After the archery duel, Richard’s army charged and vicious hand-to-hand fighting followed. (Author’s collection)

However, re-forming the soldiers into triangular or wedge formations sounds more like a pre-arranged plan, and after Oxford’s division had re-formed they charged again. It was probably at this point that the French suddenly appeared on Norfolk’s right flank, with the sun behind them. Bristling with 5m (16ft) longspears and screened by hand-gunners and crossbowmen, they crashed into Norfolk’s line and began to break it apart. Further evidence of this can be found in a fragment of a letter written by a Frenchman soon after the battle. This long-lost letter, which was quoted in a paper written by Alfred Spont in 1897, claims that Richard had shouted: ‘These French traitors are today the cause of our realm’s ruin.’ The only way that the French could have been stopped was either with the artillery, which was on the opposite flank, or the archers and hand-gunners, who were engaged in hand-to-hand fighting to their front. A third option would have been to charge them with Richard’s cavalry; however, against the pikes the chances of success were slim. The French were, in effect, unstoppable and Richard had been outmanoeuvred.

Third phase

48. Richard had a contingent of hand-gunners, possibly from Burgundy, in his army. Wildly inaccurate, slow and cumbersome, but deadly at close range. (Author’s collection)

It was during this assault that Norfolk was probably killed, although The Song of Lady Bessy says he was killed by John Savage close to Daddlington Mill. Beaumont gives an entirely different perspective in his poem, saying that Norfolk recognised Oxford by his standard, a star with rays, and charged him. He continues to describe how the lances of the two crossed and shivered as they struck the armour of the other. Renewing the combat with their swords, Norfolk wounded Oxford in the left arm before Oxford then knocked Norfolk’s bevor off. With the duke’s face exposed, Oxford chivalrously declined to continue the combat; however, Norfolk was then struck in the face by an arrow and fell dead at Oxford’s feet. This implies that they were fighting on horses, although they were much more likely to be on foot. Beaumont may have taken a degree of artistic licence when describing this and other personal combats, though he does go into extraordinary detail.

Beaumont continues: Lord Surrey, having witnessed his father’s death, set out to avenge him, but was stopped and surrounded by superior numbers. Sir Richard Clarendon and Sir William Conyers tried to rescue him but were surrounded by Sir John Savage and his retainers, and cut to pieces. In the meantime, Surrey came face to face with the veteran Sir Gilbert Talbot, who would willingly have spared the life of the young and chivalrous knight. Surrey was wounded but refused to accept quarter, and, when an attempt was made to take him prisoner, killed those who approached him. One last endeavour to capture him was made by a private soldier; Surrey, turning furiously on him, collected his remaining strength and severed the man’s arm from his body. The brave earl, worn out with loss of blood, then sank to the earth and presented Talbot with the hilt of his sword, imploring Sir Gilbert to slay him, lest he might die by some ignoble hand. Talbot, on the contrary, spared his life and had him carried from the field.

And where was Northumberland whilst the battle was raging? The Crowland Chronicle wrote that:

In the place where the earl of Northumberland was posted, with a large company of reasonably good men, no engagement could be discerned, and no battle blows given or received.

Molinet also adds:

The earl of Northumberland … ought to have charged the French, but did nothing except to flee, both he and his company, to abandon his King Richard, for he had an undertaking with the earl of Richmond, as had some others who deserted him in his need.

Was it his men in the third ‘battle’ that the chroniclers refer to as traitors? Northumberland was arrested and spent a short period in captivity after the battle, so it is unlikely that he had struck a deal with Henry. It is much more probable that after seeing the French flank attack and the collapse of Norfolk’s line, or when Richard was killed, these raw recruits panicked and ran, deciding that they did not want to suffer the same fate. Molinet reports that the vanguard which was led by the grand chamberlain of England, seeing Richard dead, turned in flight. It was Northumberland, not Norfolk, who was the chamberlain, and one version of the text actually says rearguard, so it is probable that there was an error in translating or transcribing the document at some point.

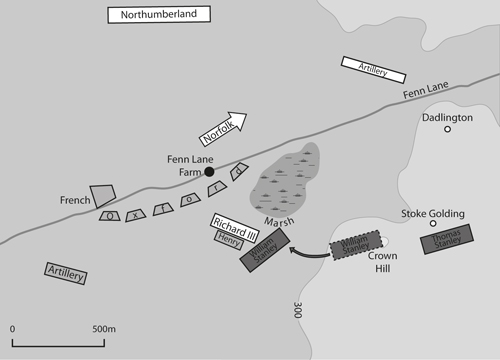

Fourth phase

The situation at this point was dire for Richard, as Norfolk’s vanguard was collapsing and Northumberland’s men were fleeing. Vergil says that:

... king Richard might have sowght to save himself by flight; for they who ever abowt him, seing the soldiers even from the first stroke to lyfc up ther weapons febly and fayntlye, and soome of them to tiepart the feild pryvyly.

This is echoed by The Ballad of Bosworth Field, which says:

... then to King Richard there came a Knight,

and said, ‘I hold itt time ffor to fflee;

ffor yonder stanleys dints they be soe wight,

against them no man may dree’.

The Song of Lady Bessy repeats much of The Ballad of Bosworth Field except that it claims the knight to be Sir William Harrington. The Castilian Report is even more specific, for it says:

Now when Salaçar, your little vassal, who was there in King Richard’s service, saw the treason of the king’s people, he went up to him and said: ‘Sire, take steps to put your person in safety, without expecting to have the victory in today’s battle, owing to the manifest treason in your following.’

The report then says that Richard replied: ‘Salazar, God forbid I yield one step. This day I will die as king or win’, and with that he put on his coat of arms and his royal crown. The Castilian Report says that the crown was worth 120,000 crowns and may have even been the original crown of Edward the Confessor, reputedly destroyed on the orders of Oliver Cromwell after the English Civil War. If it was this crown, then it was too valuable to be worn in battle and it is more likely that he would have worn a simple gold circlet.

By forming his men into wedges Oxford had created gaps in his line, and it was through one of these gaps that Henry’s standard was spotted close to the marsh. Richard saw that it was Henry himself with a small body of mounted knights and infantry; if he could just reach Henry and kill him then the battle would be over. Richard gathered his household cavalry and infantry around him and launched the last charge of the Plantagenet dynasty.

49. The last charge of the Plantagenets. Richard III’s fatal charge aimed at Henry and his bodyguards. (Author’s collection)

We do not know which route the charge took, although the ground to the east of the marsh was too boggy and at least one stream would have had to be negotiated, slowing the impetus of any charge to a trot. The deployment of the Stanleys’ forces to the east of the marsh must also be taken into account, as they had still not committed to the battle and could have blocked the cavalry before it reached Henry. Speed was of the essence, so they must have taken the shortest route – through the gaps in Oxford’s line, west of the marsh. Vergil supports this when he says: ‘he strick his horse with the spurres, and runneth owt of thone syde withowt the vanwardes agaynst him.’ Beaumont’s poem says they charged uphill, which makes sense as behind Henry was placed on the high ground.

Gathering momentum, Richard and his supporters crashed into Henry’s bodyguard. Richard killed William Brandon, Henry’s standard bearer, and the standard fell to the ground, only to be picked up by a Welshman, Rhys Fawr. Richard’s personal standard bearer, Sir Percival Thirwall, was also unhorsed and his legs cut from under him. Henry must have been close because we are told by Vergil that next in Richard’s path was:

… John Cheney a man of muche fortytude, far exceeding the common sort, who encountered with him as he came, but the king with great force drove him to the ground, making way with weapon on every side.

As Henry’s men begin to buckle under the weight of the charge, up to 3,000 fresh troops charged down from the hill into Richard’s cavalry and infantry, who were still trying to fight their way through to Henry. William Stanley had finally decided to intervene and rescue Henry. Most of Stanley’s men, like Richard’s men, were probably wearing red surcoats, which must have caused considerable confusion in trying to discern friend from foe as the two sides came to blows.

One by one, Richard’s followers were cut down in the melee that followed, before Richard himself was killed. According to Vergil he was ‘killyd fyghting manfully in the thickkest presse of his enemyes’. Molinet, on the other hand, writes that ‘His horse leapt into a marsh from which it could not retrieve itself. One of the Welshmen then came after him, and struck him dead with a halberd.’ In one version of events, it was later claimed that Rhys ap Thomas was the Welshman who killed him, although he was not a halberdier. Another version is that Ralph of Rudyard, which is near Leek in Staffordshire, dealt the fatal blow. Whoever delivered the final coup de grâce, Richard III’s courage during his last moments was unquestionable, as even his detractors agree. John Rous says that he ‘bore himself like a gallant knight and acted with distinction as his own champion until his last breath’. The Crowland Chronicle writes that ‘King Richard fell in the field, struck by many mortal wounds, as a bold and most valiant prince’. Exactly where Richard died is not known, although a proclamation by Henry soon after the battle says that it was at a place known as ‘Sandeford’. Where this was has been lost in time, but it was most likely south of the marsh at a crossing point on one of the streams that fed the marsh. Another fragment of the letter quoted in the Spont paper says that ‘he [Henry] wanted to be on foot in the midst of us, and in part we were the reason why the battle was won’. Without the rest of the letter, we do not know in what context this was said; however, it is generally accepted that it implies that Henry retired behind a wall of French pikes when Richard charged. As the French were fighting on the flank, it probably means that Henry simply wanted to be part of the main flanking attack and it was because of this attack that the battle was won.

Fifth phase

With Richard’s death, any remaining resistance quickly ended; the battle had lasted more than two hours. The cream of the Yorkist nobility was lying dead on the field, including Norfolk, Lord Ferrers, Sir Richard Ratcliffe, Sir Robert Percy, Sir Robert Brackenbury, Sir John Sacheverell and John Kendall. Many of Richard’s men threw down their weapons and surrendered or were taken prisoner; those who had not surrendered or had been captured were hunted down like animals as the rout began, with men being hacked down as they fled. There is archaeological evidence to support this in the form of a tail of battlefield debris heading north-east, away from the battle site and towards Ambion Hill. Some of the fugitives may have reached Daddlington Mill, well over 1km away, as a livery badge of an eagle with wings, probably once owned by a member of John Lord Zouche’s household, was recently found close by. It may have been in this area that the remains of the royal army made its last stand and where Zouche was captured. Some, such as Lord Lovell and the Stafford brothers, managed to escape completely and reach sanctuary at St John’s in Colchester. Catesby was not so lucky, for he was captured either at the battle or soon after and executed three days later. Significantly, Catesby along with two yeomen, both named Bracher, from the West Country were the only three to be executed after the battle, unlike the bloodbaths that followed the battles during the reign of Edward IV. Perhaps it was because Catesby was Richard’s closest advisor and Henry felt he needed to make an example of him. On the other hand, it may have been that Catesby had made too many enemies. In his will, made just after the battle on 25 August, Catesby cryptically asks the Stanleys to ‘pray for my soul as ye have not for my body, as I trusted in you’. It reads as if Catesby had surrendered to the Stanleys, who had promised him protection, but then reneged and handed him over for execution. He may have been referring to an earlier deal as well, although exactly what he really meant will probably never be known.

On Henry’s side the only notable casualty was William Brandon because, despite Richard’s orders, Lord Strange was not executed. The Song of Lady Bessy names the man given the task of executing Strange as Latham, but goes on to say that he was stopped by Sir William Harrington. Beaumont’s Ballad of Bosworth Field disagrees and says that it was Catesby who was given task, but that he was stopped by Lord Ferrers. Was this why the Stanleys handed Catesby over to Henry for execution? Although the Crowland Chronicle does not name Strange’s saviour, he does say that:

50. Victorian engraving of Henry being given the crown by Thomas, Lord Stanley. (Author’s collection)

The persons to whom this duty was entrusted, however, seeing that the issue was doubtful in the extreme, and that a matter of more weight than the destruction of one man was in hand, deferred performance of the king’s cruel order, left the man to his own disposal and returned to the thickest of the fight.

MEDICINE

If a wounded man survived the day, he would at best be cared for in one of the monastic hospitals. A valued member of a household, on the other hand, would be treated by the lord’s surgeon, so he could fight again another day. A recent excavation at the site of the Battle of Towton found the skeleton of a man who had received a horrific cut across the jaw in an earlier battle. However, the wound had been successfully treated before he fell at Towton.

We do not know who else died that day, but Vergil puts the numbers of dead as 1,000 men from Richard’s army and scarcely 100 from Henry’s. Molinet says that only 300 on either side met their demise, whilst the Castilian Report gives the total as 10,000. The truth, however, probably lies somewhere in between. With the battle over, the victors looted Richard’s baggage train and Richard’s royal regalia was collected by Henry’s officers and loaded on to his own baggage train. William Stanley was offered the pick of the rest and took a set of Richard’s tapestries, which he proudly displayed at one of his residencies, and Henry’s mother was sent Richard’s personal prayer book.

According to Vergil, with the battle over, Henry gave thanks to God for his victory and withdrew to the nearest hill. From here he thanked his commanders and nobles, knighted Gilbert Talbot, Rhys ap Thomas and Humphrey Stanley, and gave orders that all the dead should be given an honourable burial. Thomas Stanley then crowned him Henry VII with Richard’s own crown, which according to tradition was found under a thorn bush close to where Richard was killed. We do not know how true this story is, although Henry did take the image of a crown and thorn bush as one of his badges soon after. As to the site of this momentous event, part of the high ground behind Henry’s battle line, originally known as Garbrody’s Hill and Garbrod Field in the fifteenth century, was changed to Crown Hill and Crown Field before 1605, no doubt in reverence to the event.

Richard’s body was recovered from the battlefield and, according to Vergil, was ‘nakyd of all clothing, and layd uppon an horse bake with the armes and legges hanginge downe on both sides’. The scene was described by the Crowland Chronicle as a ‘miserable spectacle in good sooth’. His body was then taken back to Leicester. Hall says that he was on the horse of his Blanc Sanglier Pursuivant, an officer of arms ranking below a herald but having similar duties, but the Great Chronicle of London says that it was a pursuivant called Norroy. John Moore was the Norroy King of Arms, a senior herald with jurisdiction north of the River Trent (Nottingham), and his son was at some point Blanc Sanglier, so it could have been either. One of the legends associated with the battle says that as Richard rode across Bow Bridge en route to Bosworth, his spur clipped a stone pillar. One of those ubiquitous wise women who witnessed this supposedly announced that where his spur struck, his head would be broken. And sure enough, as Richard’s body was carried across the bridge, his head hit the same stone.