Prologue

Few people today, even in China, have heard of the little market town of Tongdao. It extends for about a mile along the left bank of the Shuangjiang, squeezed into a narrow strip of land between the wide, brown river and a range of terraced hills. Tongdao is the centre of a small non-Han minority area where the three provinces of Guangxi, Guizhou and Hunan meet. It is a scruffy, run-down place, with one long, muddy main street, few shops and fewer modern buildings, where even the locals say resignedly that nothing of interest ever happens. Yet once something did happen there. On December 12, 1934,1 the Red Army leadership gathered in Tongdao for a meeting which was to mark the beginning of Mao Zedong's rise to supreme power.

It was one of the most obscure events in the history of the Chinese Communist Party. The only written trace of the Red Army's passage is an old photograph of a faded slogan, chalked up by the troops on a wall: ‘Everyone should take up arms and fight the Japanese!’2 All the participants are now dead. No one knows exactly who was present, or even where the meeting took place. Premier Zhou Enlai, years later, recalled that it had been in a farmhouse, somewhere outside the town, where a wedding party was in progress.3 Mao was two weeks short of his forty-first birthday, a thin, lanky man, hollow-cheeked from lack of food and sleep, whose oversize grey cotton jacket seemed perpetually about to slide from his shoulders. He was still recovering from a severe bout of malaria, and at times had to be carried in a litter. Taller than most of the other leaders, his face was smooth and unmarked, with a shock of unruly black hair, parted in the middle.

The left-wing American writer, Agnes Smedley, who met Mao not long afterwards, found him a forbidding figure, with a high-pitched voice and long, sensitive woman's hands:

His dark, inscrutable face was long, the forehead broad and high, the mouth feminine. Whatever else he might be, he was an aesthete … [But] despite that feminine quality in him he was as stubborn as a mule, and a steel rod of pride and determination ran through his nature. I had the impression that he would wait and watch for years, but eventually have his way … His humour was often sardonic and grim, as though it sprang from deep caverns of spiritual seclusion. I had the impression that there was a door to his being that had never been opened to anyone.4

Even to his closest comrades, Mao was hard to fathom. His spirit, in Smedley's words, ‘dwelt within itself, isolating him’. His personality inspired loyalty, not affection. He combined a fierce temper and infinite patience; vision, and an almost pedantic attention to detail; an inflexible will, and extreme subtlety; public charisma, and private intrigue.

The nationalists, who had put a price on his head, executed his wife and sent soldiers to vandalise his parents’ tomb, viewed Mao throughout the early 1930s as the dominant Red Army political chief. As so often, they were wrong.

Power was in the hands of what was known as the ‘three-man group’ or ‘troika’. Bo Gu, the 27-year-old acting Party leader (or, as he was formally known, ‘the comrade with overall responsibility for the work of the Party Centre’) had graduated from the University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow. He had the face of a precocious schoolboy, with bulging eyes and black-rimmed spectacles, which a British diplomat said, unkindly but accurately, reminded him of a golliwog. The CominternI had parachuted him into the leadership to ensure loyalty to the Soviet line. The second member, Zhou Enlai, General Political Commissar of the Red Army and the real power behind Bo Gu's throne, also had Moscow's trust. The third, Otto Braun, a tall, thin German with a prominent nose and horsey teeth, set off by a pair of round spectacles, was Comintern military adviser.

Over the previous twelve months, these three men had presided over a shattering series of communist military reverses. The nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-shek, had consolidated his hold over most of the rest of China and was determined to extirpate what he rightly saw as a potentially fatal long-term challenge to his rule. With the help of German military advisers, he began building lines of fortified blockhouses around the region the communists controlled. With excruciating slowness, the lines were pushed forward, the vice around the base area tightened, the communist forces hemmed in. Very gradually, the Red Army was being strangled. It was a strategy to which the troika could find no adequate response.

Mao might have been no more successful. But Bo Gu had sidelined him more than two years before. Mao was not in power.

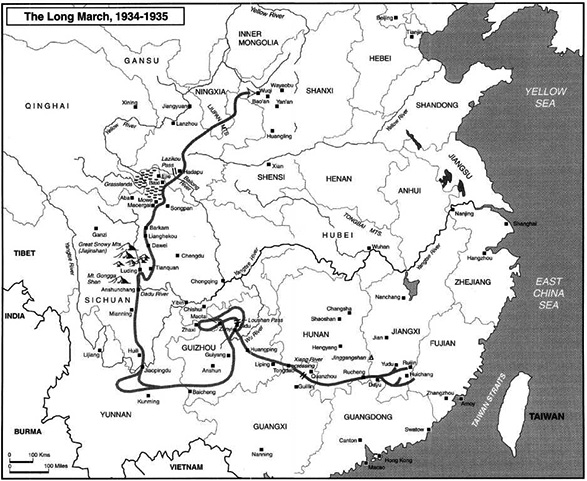

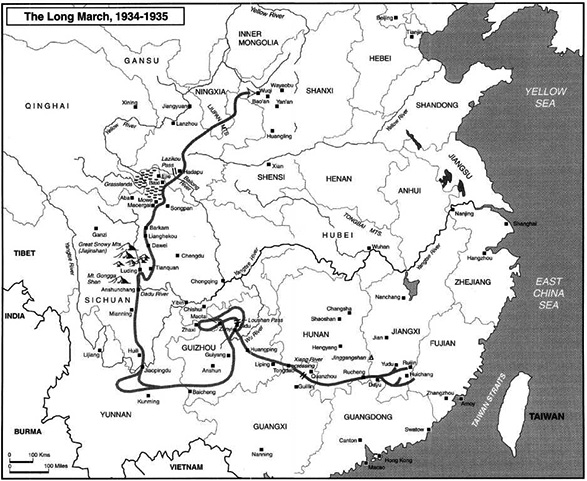

In October 1934, after months of agonised debates among the Party leadership, the Reds abandoned their base area in a last despairing gamble to ward off total defeat as Chiang's forces closed in for the kill. Their 6,000-mile trek across China would later be celebrated as the Long March, an epic symbol of courage in adversity, selfless discipline and indomitable will. At the time it was called, more prosaically, the ‘strategic transfer’, and a little later, the March to the West. The plan, in so far as there was one, was to make for north-west Hunan, where the local warlords were wary of Chiang's ambitions and reluctant to make common cause with him, and there to link up with other communist forces to create a new central Red base area to replace the one they had just lost.

It started well enough. The Red Army slipped through the first line of blockhouses, meeting little resistance. The next two lines also fell. More than three weeks passed before nationalist intelligence realised that its prey had escaped.5 But Chiang's fourth line, on the Xiang River, was different.

The battle lasted more than a week, from November 25 to December 3.6 When it ended, the Red Army had lost between 15,000 and 20,000 combat troops. Up to 40,000 reserves and bearers had deserted. Of the 86,000 men and women who had set out in October, not many more than 30,000 were left. The baggage train, which had stretched for fifty miles, a serpentine leviathan which, Mao said later, resembled a house-moving operation more than an army on the march,7 had its back broken at the Xiang River. Scattered in the mud and littering the hillsides were the office furniture, the printing presses, the Party archives, the generators – all the paraphernalia that the communists had amassed in three years’ rule of a region bigger than Belgium – which had been lugged painfully on the backs of porters over mountain paths and paddy fields for hundreds of wearisome miles. Artillery pieces, heavy machine-guns, the one X-ray machine the communists possessed, all were jettisoned. But not before they had so slowed the army's progress that, bloated and weak, it had dragged itself into the trap which Chiang Kai-shek had set.

It was a worse disaster than even the most phlegmatic Red Army leaders were prepared for. In October, the base they had spent years building had been abandoned; now two-thirds of their army had been lost as well.

A week later, having thrown off their pursuers, the remnants of the communist forces crossed into southern Hunan. They had regrouped and were in good order. But among the senior leadership, mutiny was in the air. The time was fast approaching when the troika would be called to account.

But not quite yet. The eight or nine weary men who met that afternoon at Tongdao faced a much more pressing question: where to head next? Bo Gu and Otto Braun insisted they keep to the original plan and make for north-west Hunan. The military commanders refused. Chiang Kai-shek had 300,000 troops blocking the route north. To try to force a passage was to court annihilation. A decision had to be made fast. Word came that Hunan warlord troops were closing in from the east.

After a tense, hurried debate, it was agreed as an interim measure that the army would go west, into the mountain fastness of Guizhou.8 There a full meeting of the Politburo would be called to discuss future strategy. The compromise proposal came from Mao. It was the first time since his dismissal from the military command in 1932 that his views had been heard and accepted in the inner circle of power. His presence was due only to the gravity of the Xiang River defeat. But a journey of 10,000 li, say the Chinese, starts with a single step. For Mao, Tongdao was that step.

Guizhou is, and has been for centuries, one of the poorest of China's provinces. In the 1930s, the villages were opium-sodden, the people illiterate and so impoverished that whole families possessed only a single pair of trousers. Girls were frequently killed at birth; boys were sold to slave-merchants for resale in richer areas near the coast. But it was a place of exquisite natural grandeur: the countryside that unrolled before the Red Army, as it marched west, was drawn from the fantastic landscapes of a Ming scroll.

Beyond Tongdao the hills grow steeper, the mountains wider and more contorted: great conical limestone mounds, thousands of feet high; mountains like camels’ humps, like giant anthills; plum-pudding mountains like ancestral tumuli. Miao villages perch on the bluffs – clusters of thatched roofs and ochre walls, with overhanging eaves and latticed paper windows, standing out dark against a yellowish-green carpet of dead winter grasses and early shoots of spring. Hawks circle above; frost lies white on the rice stubble below. Guizhou people say: ‘No three days without rain; no three li without a mountain.’ In this part of the province there are only mountains and, in December and January, perpetual drizzle and fog. The higher slopes, wrapped in mist, are thick with pine forests, golden bamboo and dark green firs, while far below, the valley bottoms are filled with bright lakes of white cloud. Chain bridges are slung across the rivers, and alongside the torrents that cascade down from the heights are pocket-handkerchief sized patches of cultivated land, where a peasant works on a fifty-degree slope to coax a few poor vegetables from the dark red soil.

The soldiers remembered only the rigours of the journey. ‘We went up a mountain so steep that I could see the soles of the man ahead of me,’ one army man recalled. ‘News came down the line that our advance columns were facing a sheer cliff, and … to sleep where we were and continue climbing at daybreak … The stars looked like jade stones on a black curtain. The dark peaks towered around us like menacing giants. We seemed to be at the bottom of a well.’9 The cliff, known locally as the Thunder God Rock, had stone steps a foot wide carved into its face. It was too steep for stretcher-bearers: the wounded had to be carried up on men's backs. Many horses fell to their deaths on the rocks below.10

The Red Army Commander, Zhu De, remembered the poverty. ‘The peasants call themselves “dry men”,’ he noted. ‘They are sucked dry of everything … People dig rotten rice from the ground under a landlord's old granary. The monks call this “holy rice”, Heaven's gift to the poor.’11

Mao saw these things too. But he wrote instead of the power and beauty of the country through which they were passing:

Mountains!

Surging waves in a tumultuous sea,

Ten thousand stallions

Galloping in the heat of battle.

Mountains!

Blade-sharp, piercing the blue of heaven.

But for your strength upholding

The skies would break loose and fall.12

These short poems, composed in the saddle, were not simply a celebration of the elemental forces of nature. Mao had reason to exult.

*

On December 15, the Red Army reached Liping, a county seat in a valley surrounded by low, terraced hills, and the first level ground they had seen since leaving Tongdao. Military headquarters were set up in a merchant's house, a spacious, well-appointed place with a small inner courtyard, ornamented by Buddhist motifs and emblems of prosperity. It had four-poster beds and a tiny Chinese garden behind, and opened on to a narrow street of wood-fronted shops and houses with grey-tiled roofs and upturned bird's-wing eaves. A few doors further down stood a German Lutheran mission. The missionaries, like the merchant, had fled at the communists’ approach.

It was here that the Politburo met for its first formal discussion of policy since the Long March began.13 There were two main issues: the Red Army's destination, which was still unresolved; and military tactics.

Braun and Bo Gu wanted to join up with the communist forces in northern Hunan. Mao proposed heading north-west, to set up a new Red base area on the border between Guizhou and southern Sichuan, where, he argued, resistance would be weaker. He was supported by Zhang Wentian, one of the four members of the Politburo Standing Committee, and Wang Jiaxiang, Vice-Chairman of the Military Commission, who had been gravely wounded in battle a year earlier and spent the whole of the Long March in a litter with a rubber tube sticking out of his stomach. Both were Moscow-trained. Both had initially backed Braun and Bo Gu but had grown disillusioned. Mao had been cultivating them ever since the march began. Now they swung the balance in his favour. Sensing the mood of the meeting, Zhou Enlai added his voice and most of the rest of the Politburo fell in behind. Bo Gu's proposal was rejected. Instead they resolved to set up a new base area with its centre at Zunyi, Guizhou's second city, or, if that proved too difficult, further to the north-west.

But Mao did not have it all his own way. On tactics, the resolution was more even-handed. It warned against ‘underestimating possible losses to our own side, leading to pessimism and defeatism’ – an implicit reference to the rout on the Xiang River and thus a criticism of the military line of the three-man group of Zhou, Bo Gu and Braun; in the same vein, it ordered the army to refrain from large-scale engagements until the new base area had been secured. But it also spoke of the danger of ‘guerrillaism’, a codeword for the ‘flexible guerrilla strategy’ associated with Mao. Zhou Enlai evidently was not prepared to yield to Mao without a fight.14

Next day, December 20, the Red Army resumed its march. Bo Gu and Otto Braun were fatally weakened. The real conflict shaping up was now between Mao and Zhou.

They had so little in common, these two men: Zhou, a mandarin's son, a rebel against his class, supple, subtle, the quintessential survivor, who had learned the cheapness of life as a communist working underground in Shanghai, where death was never more than a whisper of betrayal away; Mao, a peasant to his roots, earthy and coarse, his speech laced with picaresque aphorisms, contemptuous of city-dwellers. One was urbane and refined, the indefatigable executor of other men's ideas; the other, an unpredictable visionary. For most of the next forty years they would form one of the world's most enduring political partnerships. But as 1934 drew to a close, that was far from both their minds.

On December 31, the army command halted at a small trading centre called Houchang (Monkey Town), twenty-five miles south of the River Wu, the last natural barrier before they reached Zunyi.15 That night the Politburo met again. Otto Braun proposed that the army make a stand against three warlord divisions which were reported to be closing in on them. The military commanders reminded him that they had agreed at Liping to avoid large-scale set-piece battles and give priority to securing the new base area. After a furious argument lasting late into the night, Braun was suspended as military adviser. To underline the importance of the change, the Politburo resolution approving it included a ringing endorsement of one of Mao's cardinal principles, which had been ignored for the previous two years. ‘No opportunity should be missed,’ it declared, ‘to use mobile warfare to break up and destroy the enemy one by one. Then we shall certainly gain victory.’

The tide had turned. The old chain of command under the troika had broken down. As a temporary measure, it was agreed that all major decisions would be referred to the leadership as a whole. The old strategy had been abandoned. A new one had to be worked out to replace it. In the early hours of New Year's Day, the Politburo agreed to convene an enlarged conference at Zunyi. It was to have three tasks: to review the past, determine what had gone wrong, and chart a course for the future. The stage was set for a showdown.

Deng Xiaoping was thirty years old, a stocky man, very short, with a close-shaven bullet head. As a teenager in Paris he had learned how to produce a news-sheet for the local branch of the Chinese Communist Youth League, scratching characters on to a waxed sheet with a stylus and rolling off copies in black Chinese ink, made from soot and tung oil. His reputation as a journalist had stuck. Now he was editor of the Red Army newspaper, an equally crude mimeographed one-page broadsheet called Hongxing (Red Star).

The issue of January 15, 1935, related how the people of Zunyi had welcomed the communist forces after they had taken the city without a shot being fired: the advance guard had persuaded the defenders to open the city gates by pretending to be part of a local warlord force. Other articles described in glowing terms ‘the Red Army's image in the hearts of the masses’, and recorded the establishment of a Revolutionary Committee to administer the city.16

Nowhere did it give the slightest hint that the Politburo was about to hold the most important meeting in its history, which Deng himself would attend as note-taker – a meeting so sensitive that, for almost a month after, senior Party officials were kept in ignorance of its decisions, until the leaders had met again to decide how the news should be broken to them.

Twenty men gathered that night on the upper floor of a handsome, rectangular, two-storey building of dark-grey brick, surrounded by a colonnaded veranda.17 It had been the home of one of the city's minor warlords until Zhou and the military commanders took it for their headquarters. Bo Gu and Otto Braun were billeted close by, along a lane leading to the Roman Catholic Cathedral, an ornate, imposing structure with a fanciful three-tiered roof, more chinoiserie than Chinese, set amid flower gardens where the Red Army detachment escorting the leadership was encamped. Mao and his two allies, Zhang Wentian and Wang Jiaxiang, with six bodyguards, were in another warlord's house, with art-deco woodwork and stained-glass windows, on the other side of town. Ever since they had arrived, a week earlier, Mao had been canvassing support. Now the preparations were over. The two sides were ready to do battie. In Otto Braun's words:

It was obvious that [Mao] wanted revenge … In 1932 … his military and political [power] had been broken … Now there emerged the possibility – years of partisan struggle had been directed at bringing it about – that by demagogic exploitation of isolated organisational and tactical mistakes, but especially through concocted claims and slanderous imputations, he could discredit the Party leadership and isolate … Bo Gu. He would rehabilitate himself completely [and] take the Army firmly into his grasp, thereby subordinating the Party itself to his will.18

The small, crowded room where the meeting was held overlooked an inner courtyard. In the centre, a brazier full of glowing charcoal threw its puny heat at the damp, raw cold of the Zunyi winter. Wang Jiaxiang and another wounded general lay stretched out on bamboo chaise-longues. Braun and his interpreter sat away from the main group, near the door.

Bo Gu, as acting Party leader, presented the main report. He argued that the loss of the central Red base area and the military disasters that had followed were due not to faulty policy, but to the enemy's overwhelming strength and the support the nationalists had received from the imperialist Powers.

Zhou Enlai spoke next. He acknowledged having made errors. But he, too, refused to concede that the policy had been wrong. Zhou still had hopes of saving something from the ruins.

Zhang Wentian then presented the case for a change in strategy, which had been alluded to though not discussed openly at Liping and Houchang, and Mao followed up with a full-scale attack on the troika and its methods.19 Braun remembered, forty years later, that he spoke not extempore, as he usually did, but from a manuscript, ‘painstakingly prepared’.20 The fundamental problem, Mao said, was not the strength of the enemy: it was that the Party had deviated from the ‘basic strategic and tactical principles with which the Red Army [had in the past] won victories’, in other words, the ‘flexible guerrilla strategy’ which he and Zhu De had developed. But for that, he claimed, the nationalist encirclement would probably have been defeated. Instead, the Red Army had been ordered to fight a defensive, positional war, building blockhouses to counter the enemy's blockhouses, dispersing its forces in a vain attempt to preserve ‘every inch of soviet territory’ and abandoning mobile warfare. Temporarily surrendering territory could be justified, Mao said. Jeopardising the Red Army's strength could not, because it was through the army – and the army alone – that territory could be regained.21

Mao laid the blame for these errors squarely on Otto Braun. The Comintern adviser had imposed wrong tactics on the army, he said, and his ‘rude method of leadership’ had led to ‘extremely abnormal phenomena’ within the Military Council, a reference to Braun's hectoring, dictatorial style, which was widely resented. Bo Gu, Mao declared, had failed to exert adequate political leadership, allowing errors in military line to go unchecked.

When Mao sat down, Wang Jiaxiang launched his own tirade against Braun's methods. Another Moscow-trained leader, He Kaifeng, then sprang to Bo's defence. Some of those present, like Chen Yun, a former print-worker who had been close to Zhou in Shanghai, found Mao's attack one-sided.22 Although Chen had no military role, he was a Standing Committee member and his opinions carried weight. Others may have had in the back of their minds a message received from Wang Ming in Moscow shortly before they left the base area, indicating that the Comintern took a favourable view of Mao's experience as a military leader.23 The ground commanders, whose armies had had to pay the price of the troika's mistakes, also weighed in. Peng Dehuai, a gruff, outspoken general who cared for only two things in life, the victory of the communist cause and the welfare of his men, likened Braun to ‘a prodigal son, who had squandered his father's goods’ – a reference to the loss of the base area for which Peng, with Mao and Zhu, had expended so much time and blood.

Braun himself sat immobile in his corner near the door, smoking furiously, as his interpreter, growing increasingly agitated and confused, tried to translate what was said. When he finally spoke, it was to reject the accusations en bloc. He was merely an adviser, he said; the Chinese leadership, not he, was responsible for the policies it followed.

This was disingenuous. Under Stalin in the 1930s a Comintern representative, even an adviser, had extraordinary powers. Yet there was some truth in what he said. Braun had not had the last word on military affairs. That had rested with Zhou Enlai.

Mao had no illusions that Zhou was his real adversary. He had known it since Zhou had arrived in the Red base area at the end of 1931 and unceremoniously elbowed him aside. Neither the amiable Zhang Wentian nor, still less, Bo Gu, was a serious contender for ultimate power. Zhou Enlai was. But to have attacked Zhou head-on at Zunyi would have been to tear the leadership apart in a battle which Mao could not win. So, in a move characteristic of his political and military style, he concentrated his attack on the weakest points of Zhou's armoury, Braun and Bo Gu, while leaving his chief opponent a face-saving way out.

Zhou took it. On the second day of the conference he spoke again. This time he acknowledged that the military line had been ‘fundamentally incorrect’, and made a lengthy self-criticism. It was the kind of manoeuvre at which Zhou excelled. From being Mao's opponent, he transformed himself into an ally. Mao, of course, knew better. So did Zhou. But for the moment there was a truce.

The resolution drawn up afterwards excoriated Zhou's two colleagues in the troika for their ‘extremely bad leadership’. Braun was accused of ‘treating war as a game’, ‘monopolising the work of the Military Council’ and using punishment rather than reason to suppress ‘by all available means’ views which differed from his own. Bo Gu was held to have committed ‘serious political mistakes’. But Zhou escaped unscathed, even managing, on paper at least, to achieve a short-lived promotion: when the troika was officially dissolved, he took over its powers with the cumbersome title of ‘final decision-maker on behalf of the Central Committee in dealing with military affairs’. His role in the débâcle that had preceded the Zunyi conference was passed over in silence. The resolution condemned the ‘elephantine’ supply columns which had slowed the advance, but omitted to say that it was Zhou who had organised them. It referred to ‘the leaders of the policy of pure defence’, and on one occasion, to ‘Otto Braun and the others’, but did not say who those ‘others’ were. Zhou was mentioned explicitly only once, as having given the ‘supplementary report’ following Bo Gu's. Even then, in all copies of the resolution except those distributed to the highest-ranking cadres, the three characters of his name were left blank.

Mao was named to the Politburo Standing Committee, and became Zhou's chief military adviser. Small recompense, it might seem, for two years in the wilderness. But, as so often in China, the spirit of these decisions counted far more than the letter. Even Braun acknowledged that ‘most of those at the meeting’24 ended up in agreement with Mao. In spirit, Mao's cause had triumphed. Zhou, notwithstanding his new title, was identified with the discredited leadership whose policies had been condemned.

Over the next few months the spirit was given flesh.25 Early in February, Bo Gu was replaced as acting Party leader by Mao's ally, Zhang Wentian. A month later a Front Headquarters was established, with Zhu De as Commander and Mao as Political Commissar, which effectively removed a large measure of Zhou's operational control. Soon afterwards, his power was further eroded when a new troika was established, consisting of Zhou, Mao, and Wang Jiaxiang. By early summer, when the Red Army succeeded in crossing the River of Golden Sand into Sichuan, Mao had established himself as its uncontested leader.

Other battles lay ahead. It would be eight more years before Mao was formally installed as Chairman, the title he would keep until his death. But Zhou's challenge was over. He would pay dearly for it. In 1943, his position was so precarious that the former head of the Comintern, Georgii Dimitrov, pleaded with Mao not to have him expelled from the Party.26 Mao kept him. Not because of Dimitrov but because Zhou was too useful to waste. The future Premier was instead humiliated. In the new Party Central Committee, formed two years later, he ranked twenty-third.

Twenty-five years after Zunyi, in the spring of 1961, Mao was aboard his private train, travelling through his home province of Hunan in southern China.27

The years seemed to have been good to him. Adulated and glorified as China's Great Helmsman, the ageing, corpulent figure whose moon face gazed out serenely from the Gate of Heavenly Peace appeared to the rest of the world as undisputed ruler of the most populous nation on earth and standard-bearer of a puritanical global revolution which the fleshpots of Khrushchevite revisionism had abandoned.

Yet Mao was not as the rest of the world imagined.

He was accompanied on this journey, as on all such trips, by a number of attractive young women with whom he shared, severally or together, the pleasures of an oversized bed, which was specially installed wherever he went, not so much for carnal reasons as to accommodate the piles of books he insisted on keeping at his side.28 Like Stalin, who, after his wife's suicide, was provided with attractive ‘housekeepers’ by his security chief, Lavrentii Beria, Mao in late middle age had given up on family life. He found in his relations with girls a third his own age a normality which was denied him elsewhere.

By the 1960s Mao was totally cut off from the country that he ruled, so isolated by his eminence that bodyguards and advance parties choreographed his every move. Sex was his one freedom, the one moment in his day when he could treat other human beings as equals and be treated as such in return. A century earlier the boy Emperor, Tongzhi, used to slip out of the palace incognito, accompanied by one of his courtiers, to visit the brothels of Beijing. For Mao that was impossible. Women came to him. They revelled in his power. He revelled in their bodies. ‘I wash my prick in their cunts,’ he told his personal physician, a strait-laced man whom he took a perverse delight in shocking. ‘I was nauseated,’ the good doctor wrote afterwards.29

Mao's peccadilloes, like the private lives of all the leaders, were hidden behind an impenetrable curtain of revolutionary purity. But on the train one afternoon that February, the veil was suddenly pierced.

He had spent the night with a young woman teacher and, as was his custom, had risen late and then left to attend a meeting. Afterwards she was talking with other members of Mao's suite when a technician joined them. Mao's doctor takes up the story:

‘I heard you talking today,’ the young technician suddenly said to the teacher, interrupting our idle chatter.

‘What do you mean you heard me talking?’ she responded. ‘Talking about what?’

‘When the Chairman was getting ready to meet [Hunan First Secretary] Zhang Pinghua, you told him to hurry up and put on his clothes.’

The young woman blanched. ‘What else did you hear?’ she asked quietly.

‘I heard everything,’ he answered, teasing.30

Thus did Mao discover that, on the orders of his senior colleagues, for the previous eighteen months all his conversations, not to mention his lovemaking, had been bugged and secretly tape-recorded.31 At the time, the only heads to roll, and those not literally, were of three low-level officials, among them the hapless technician. But four years later, when the first political tremors announcing the Cultural Revolution began to roil the surface calm of Party unity, Mao's fellow leaders would have done well to have reflected more deeply on what had led them to approve those secret tape-recordings.

In one sense their motives had been innocent enough. The six men who, with Mao, made up the Politburo Standing Committee, at the summit of a Party which now counted 20 million members, were all Zunyi veterans, part of the minuscule elite which had accompanied him throughout the long odyssey to win power. By the early 1960s, they found the Chairman increasingly difficult to read. They wanted advance warning of what he was thinking, so as not to be caught off-guard by a sudden change in political line or an off-the-cuff remark to a foreign visitor. Yang Shangkun, another Zunyi survivor, who headed the Central Committee's General Office, decided that modern technology, in the shape of recording machines, was the obvious answer. From that standpoint it was almost a compliment. Mao had achieved such Olympian status that his every word must be preserved. But it also reflected an uneasy awareness within the Politburo of the mental gulf that had developed between the Chairman and his subordinates – which was all that the other leaders now were.

From this mental chasm sprang an ideological and political divide which, before the decade was out, would convulse all China in an iconoclastic spasm of terror, destroying both the Zunyi fellowship and the ideas that it had espoused.

The struggle in the 1960s was more subtle, more complex, and ultimately far bloodier and more ruthless than that of thirty years before. Small wonder: all that had been at stake at Zunyi was the leadership of a ragtag army of 30,000 men playing an apparently dwindling role on the periphery of Chinese politics. In Beijing the battle was for control of a nation which would soon number more than a billion people. But the ground rules were the same. On that earlier occasion, Mao himself had spelt them out:

Under unfavourable conditions, we should refuse … battle, withdraw our main forces back to a suitable distance, transfer them to the rear or flanks of the enemy and concentrate them in secret, induce the enemy to commit mistakes and expose weaknesses by tiring and wearing him out and confusing him, and thus enable ourselves to gain victory in a decisive battle.32

‘War is politics,’ he wrote later. ‘Politics is war by other means.’33

I The Communist International (Comintern) was established by Lenin, in March 1919, as an instrument whereby Moscow could control the activities of foreign communist parties. These were treated as Comintern branches under the orders of a Russian-dominated Executive Committee.