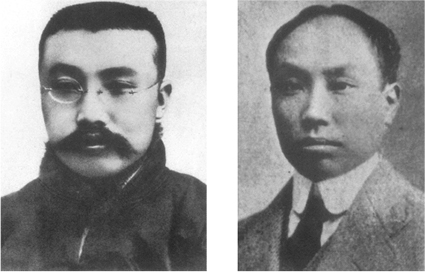

Plate 1 The earliest known portrait of Mao, as a teenager around the time of the 1911 revolution.

CHAPTER FIVE

The Comintern Takes Charge

On Friday, 3 June, 1921, the Lloyd Triestino steamer, the Acquila, docked at Shanghai after a six-week voyage from Venice. Among the passengers who disembarked was a Dutchman. Powerfully built, in his late thirties, with close-cropped dark hair and a swarthy moustache, he reminded those who met him of a Prussian army officer.1 He had had a trying journey. Even before he took ship, he had been arrested in Vienna, where he had gone to obtain a Chinese visa. A week later the Austrian police released him, but not before notifying the governments of all the countries for which he had entry permits in his passport. At Colombo, Penang, Singapore and Hong Kong, the British posted police guards at the docks to prevent him going ashore. The Dutch Legation in Beijing asked the Chinese government to deny him entry too, but received no reply.2 Shanghai was a law unto itself, where Beijing's writ did not run. It was the soft, wet maw of China, which, with each new tide, sucked in the dispossessed, the ambitious and the criminal – ruined White Russian families, Red adventurers, Japanese spies, stateless intellectuals, scoundrels of every stripe – and sent out in return idealistic youths, seeking foreign learning in Tokyo and Paris. The Chinese called the city a ‘hot din of the senses’. To foreigners, it was ‘the Whore of the East’. The aesthete, Sir Harold Acton, remembered it as a place where ‘people had no idea how extraordinary they were; the extraordinary had become ordinary; the freakish commonplace’. Wallis Simpson was rumoured to have posed nude, with only a lifebelt round her, for a local photographer.

Eugene O'Neill, accompanied by a Swedish masseuse, had a nervous breakdown in Shanghai. Aldous Huxley wrote of its ‘dense, rank, richly clotted life … nothing more intensely living can be imagined.’ The journalist, Xia Yan, saw ‘a city of 48-storey skyscrapers, built upon 24 layers of hell’.3

Mr Andresen, as the Dutchman called himself, proceeded along the bund, past the towering, granite-built citadels of British capitalism – the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, the Customs House with its mosaic ceiling of Yangtse river junks, Jardine & Matheson, and the East Asiatic Company – past the park with its apocryphal sign, ‘Chinese and dogs not allowed’,4 past the Seamen's Hostel and Suzhou Creek, to take a room at the Oriental Hotel.5

As he looked around him, at the pavements crowded with Chinese men, wearing long gowns and Panama hats; immaculately dressed taipans in chauffeur-driven sedans; nightclubs full of Eurasian taxi-dancers, where young expatriates caroused through the night; ragged coolies, glistening with sweat, straining at huge loads; the textile mills, in which women and children worked fourteen-hour shifts; and the filthy slums across the river, where this emerging new proletariat lived, he might have been forgiven for feeling a surge of missionary zeal. For Hendricus Sneevliet, to give him his real name, also known as Martin Ivanovich Bergman, Comrade Philipp, Monsieur Sentot, Joh van Son and Maring, amid a host of other aliases, was a missionary of a kind. He had been sent to China by Lenin as the first representative of the Comintern, the Communist International, to help the Chinese comrades organise a party which would give fraternal support to the Bolshevik leadership in ‘Mekka’, as he referred to Moscow, and help spread the worldwide revolution in which they all fervently believed.6

Sneevliet was not the first Russian emissary to China. Initial contact had been made in January 1920. Then in April, with the Comintern's approval, Grigorii Voitinsky had been sent on a fact-finding visit by the Vladivostok branch of the Bolshevik party's Far Eastern Bureau. Its headquarters were at Chita (Verkhneudinsk), the capital of the Soviet Far Eastern Republic, a vast territory nominally independent from Moscow which extended from the Chinese border to southern Siberia. The Bureau engaged in constant turf battles with the Far Eastern Republic's Foreign Ministry, with the ‘Eastern People's Section’ of the Russian party's Siberian Bureau, based at Irkutsk, and occasionally, for good measure, with the Comintern itself. The result was that more than a dozen Russian agents, often at cross purposes with each other, were active in China that year, as well as a number of Korean communists, some of whom claimed to represent the Comintern and who were also divided among themselves. The Chinese were equally disorganised. Voitinsky found himself confronted by a range of Chinese claimants to Soviet support. Most were anarchists who saw the Comintern as a potential source of money and recognition. One such movement, the Great Unity Party (Datongdang), succeeded for a time in gaining acceptance by the Bureau in Vladivostok as an authentic ‘socialist, communist’ organisation. Another briefly existed as a Chinese branch of the Russian Communist Party. It was not until after Sneevliet's arrival that the Comintern, at its Third Congress in Moscow in June 1921, recognised Chen Duxiu's movement as the only legitimate communist force in China, rejecting the claims of four other self-proclaimed Chinese communist organisations. By then the Russians had got their own act together, having amalgamated the Chita and Vladivostok operations into the Comintern's Far Eastern Secretariat which replaced the ‘Eastern People's Section’ in Irkutsk.7

Voitinsky's arrival had been skilfully timed to coincide with the upsurge of enthusiasm for the Soviet Union triggered by Moscow's announcement that it would renounce its extraterritorial rights. He was a man of great tact and charm, and the Chinese with whom he had dealings saw him as the perfect example of everything a revolutionary comrade should be. During the nine months he spent in China, he helped Chen Duxiu organise the ‘communist group’ in Shanghai, the Socialist Youth League and the communist journal, Gongchandang, and drafted the Party Manifesto, which Mao and others received that winter, as a preliminary to holding a founding Congress to bring the provincial groups together to form a full-fledged Communist Party.

Hendricus Sneevliet was a man of a very different stamp. He was a member of the Executive Committee of the Comintern, and had already spent five years in Asia as an adviser to the Communist Party of Dutch-ruled Indonesia. He exuded a mixture of obstinacy and arrogance which signalled not only that he knew better than any of the Chinese comrades, but that it was his bounden duty to bring them into line. Zhang Guotao, a Beijing graduate who had helped Li Dazhao set up the North China ‘communist group’, recalled their first meeting, shortly after the Dutchman's arrival:

This foreign devil was aggressive and hard to deal with; his manner was very different indeed from that of Voitinsky … He left the impression with some people that he had acquired the habits and attitudes of the Dutchmen that lived as colonial masters in the East Indies. He was, he believed, the foremost authority on the East in the Comintern, and this was a great source of pride to him … He saw himself coming as an angel of liberation to the Asian people. But in the eyes of those of us who maintained our self-respect and who were seeking our own liberation, he seemed endowed with the social superiority complex of the white man.8

At the end of June 1921, Mao and He Shuheng left Changsha by steamer, amid great secrecy, to join eleven other delegates, representing Beijing, Canton, Jinan, Shanghai, Tokyo and Wuhan, to attend the founding Congress which Voitinsky had initiated.9 It began on Saturday July 23 – three days later than planned because some of the delegates were delayed – in a classroom at a girls’ school in the French concession which had closed for the summer holidays. Neither Chen Duxiu nor Li Dazhao was present, apparently because the Congress had been called at short notice and they had other commitments. In their absence the proceedings were chaired by Zhang Guotao, whom Mao had met in Beijing two-and-a-half years earlier when he had worked as a library assistant there. Sneevliet and a colleague, Nikolsky, who represented the newly established Far Eastern Secretariat in Irkutsk, led the initial proceedings, but then the meeting recessed for two days to allow a drafting committee to produce texts of a Party programme, Party rules and a statement of Party policy.

When it resumed the following Wednesday, the discussion turned on three points: what kind of party they should create; what stance it should adopt towards bourgeois institutions, specifically the National Parliament and the Beijing and Canton governments; and its relationship with the Comintern.

Sneevliet, in his opening address, noting that all those present were students or teachers, had stressed the importance of forging strong links with the working class. The Marxist scholar, Li Hanjun, who represented the Shanghai group, immediately disagreed. Chinese workers, he retorted, understood nothing of Marxism. It would take a long period of education and propaganda work before they could be organised. In the meantime, Chinese Marxists needed to decide whether their cause would best be served by an organisation propagating Russian Bolshevism or German-style Social Democracy. To rush headlong into building a working-class party, dedicated to proletarian dictatorship, would be a serious mistake. Sneevliet was scandalised. On this issue the Dutchman carried the day, and in its first formal statement, the new Chinese Communist Party (CCP) declared in true Bolshevik fashion:

The programme of our party is as follows: With the revolutionary army of the proletariat, to overthrow the capitalistic classes and to reconstruct the nation from the working class until class distinctions are eliminated … To adopt the dictatorship of the proletariat … To overthrow the private ownership of capital, to confiscate all the means of production, such as machines, land, buildings … and so on, and to entrust them to social ownership … Our party, with the adoption of the soviet form, organises the industrial and agricultural labourers and soldiers, propagates communism, and recognises the social revolution as our chief policy; it absolutely cuts off all relations with the yellow intellectual class and other such groups.10

On the other two points in dispute, the outcome was less satisfactory to Moscow. This was partly because of the way the Congress ended. On July 29, when it became clear that serious disagreements remained, Sneevliet said he wished to put forward some new ideas and asked that the next session take place not at the school but at Li Hanjun's house, which was also in the French Concession. Soon after the meeting began, a man looked through the door, muttered something about having come to the wrong house and hurriedly departed. On Sneevliet's instruction, the delegates immediately dispersed. A group of Chinese detectives, led by a French officer, arrived a few minutes later, but despite a four-hour search, found nothing. After that, it was thought too dangerous to hold further meetings in Shanghai, and the final session was held some days later on a pleasure boat on the reed-fringed South Lake at Jiaxing, a small town on the way to Hangzhou, sixty miles to the south. There, too, Sneevliet was unable to speak: it was felt that the presence of foreigners would make the group too conspicuous, so he and Nikolsky did not take part. As a result, when the boat trip ended at dusk, and the delegates shouted in unison, ‘Long live the [Chinese] Communist Party, long live the Comintern, long live Communism – the Emancipator of Humankind’, they had taken what one of them called ‘many furious and radical decisions’, not all of them to the Comintern's liking.11

They had resolved, for instance, to adopt ‘an attitude of independence, aggression and exclusion’ towards other political parties, and to require Communist Party members to cut all ties with non-communist political organisations.12 This sectarian stance was at odds not only with Sneevliet's hopes for a tactical alliance with Sun Yat-sen's Guomindang, which he rightly saw as the strongest revolutionary force in China at that time, but also with Lenin's thesis, approved by the Second Comintern Congress in Moscow a year earlier, that communist parties in ‘backward countries’, in so far as they were able to exist at all, would have to work closely with national-revolutionary bourgeois democratic movements.13

Had the Congress[Q1] been able to continue until August 5, as originally planned, Sneevliet might have been able to convince them to adopt a programme better suited to China's conditions. As it was, the delegates approved virtually unchanged the drafting committee's proposals – made without Sneevliet's participation – which were modelled on the programme and manifesto of the United States Communist Party, translations of which had been printed in Gongchandang in December, and the statutes of the British Communist Party.14

No less troubling, the delegates failed to reach agreement on the respective merits of the Beijing and Canton governments. In Sneevliet's eyes, as in Chen Duxiu's, the southern regime was much more progressive.

Still worse, from the Dutchman's perspective, the delegates refused to acknowledge Moscow's supremacy. Although the Party programme spoke of ‘uniting with the Comintern’, the Chinese Party saw itself as an equal, not a subordinate.15 The Russians were not happy. Nikolsky's boss in Irkutsk, Yuri Smurgis, spoke dismissively of a Congress of ‘Chinese who fancied themselves communists’.16

In these circumstances, tensions with ‘Mekka’ were bound to continue.

When Chen Duxiu took up his responsibilities as Secretary of the provisional Central Executive Committee in September, he found that Sneevliet, as Comintern representative, was not only issuing orders to Party members on his own authority, but expected him to submit a weekly work report.17

For several weeks, Chen refused to have anything to do with the Dutchman. The Chinese Party was in its infancy, he told members of the Shanghai group. China's revolution had its own characteristics, and did not need Comintern help. Eventually a modus vivendi was realised, mainly because, Chen's disclaimers notwithstanding, the Comintern provided the money, upwards of 15,000 Chinese dollars a year, which the Party needed to survive.18 But bad blood remained, and not only because of Sneevliet's authoritarian style. He was to be the first in a long line of Soviet advisers to offend Chinese sensibilities, reflecting a cultural and racial divergence which the internationalism of the communist movement initially papered over, but which forty years later would exact its own revenge.

Mao played a minor role in the First Congress. He made a report (which has been lost) on the work of the Hunan group,19 which by July accounted for ten of the fifty-three members of the communist movement in China;20 and he and Zhou Fuhai, a Hunanese student representing the Tokyo group, which boasted all of two members, were appointed official note-takers.21 Zhang Guotao remembered him as a ‘pale-faced youth of rather lively temperament, who in his long gown of native cloth looked rather like a Daoist priest out of some village’. Mao's ‘rough, Hunanese ways’, Zhang wrote, were matched by a fund of general knowledge but only a limited understanding of Marxism.22 None of the participants recall him having contributed much to the debates.23 He evidently felt intimidated by his more sophisticated companions, most of whom, he told his friend Xiao Yu, who was visiting him in Shanghai at the time, ‘are very well-educated, and … can read either Japanese or English’.24 That brought back all his old feelings of inadequacy about languages, and as soon as he returned to Changsha, he plunged into his English lessons again.25 Two months later, the Hunan branch of the CCP was established, with Mao as its Secretary, on the symbolic date of October 10, the anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution launched ten years before.26

For the next few months, Mao devoted himself to building up the Party's tiny following. In November, the provisional Party Centre issued a directive, requiring each provincial branch to have at least thirty members by the summer of 1922.27 Mao's branch was one of three to meet the target, the others being Canton and Shanghai.28 The same month he organised a parade to celebrate the Bolshevik Revolution. This became an annual event, drawing coverage from the Republican daily, Minguo ribao, in Shanghai:

An immense red flag fluttered from the flagpole on the esplanade in front of the Education Association building, with on each side two smaller white banners, bearing the slogan: ‘Proletarians of the World, Arise!’ Other small white flags were inscribed, ‘Long live Russia! Long live China!’ Then came a multitude of small red flags, on which were written: ‘Recognise Soviet Russia!’ … ‘Long live socialism!’ and ‘Bread for the workers!’ Tracts were handed out to the crowd. Just as the speech-making was about to begin, a detachment of police appeared, and the officer in charge announced that, by order of the Governor, the meeting must disperse. The crowd protested, invoking Article 12 of the Constitution, which gave citizens the right of free assembly … But the officer refused to discuss it, and said the Governor's order must be obeyed. The crowd grew angry and shouted: ‘Down with the Governor!’ At that, the police set about their business. All the flags were torn down and the demonstrators forcibly dispersed. It was 3 o'clock in the afternoon, and torrential rain began to fall, preventing any farther resistance.29

Such tensions with Governor Zhao notwithstanding, Mao was able to win enough support from his allies in the provincial elite to establish the ‘Self-study University’ of which he had written a year earlier, financed by an annual local government grant of some 2,000 Chinese dollars, a substantial sum for the time.30

The school's stated objectives were ‘to prepare for reforming society’ and ‘to bring together the intellectual class and the working class’.31 In practice it served as a training ground for future Party activists, numbering at its peak some two dozen full-time students. At first, the fact that it was sponsored by the Wang Fuzhi Society, and was housed in the former Wang Fuzhi Academy, obscured this political purpose, but with time it came closer to Mao's original concept of an academic commune, where teachers and students ‘practised communist living’. Mao gave up his job at the primary school to serve as the university's director, while also teaching Chinese at First Normal.32 He Shuheng was academic dean. He Minfan acted as Principal, until Mao's unconventional ideas about health and fitness caused them to fall out. In the sweltering heat of the Changsha summer, Mao encouraged the students to attend classes in what by the standards of the time was considered a scandalous state of undress. He Minfan, who was of an earlier, more conservative generation, was deeply offended, and after other disagreements they parted on bad terms.33

The main thrust of Mao's activities over the next two years, however, was as a labour organiser. Bolshevik orthodoxy held that the revolution must be built by the proletariat, and the First Congress had laid down that the ‘chief aim’ of the Party was to establish industrial unions.34 There were then about one-and-a-half million industrial workers in China, as against 250 million peasant farmers.35 Conditions in the factories were Dickensian. The noted American labour campaigner, Dr Sherwood Eddy, reported after an investigation in China on behalf of the YMCA:

At the Beijing match factory, there are 1,100 workers, many of them boys between 9 and 15 years old. Work starts at 4 a.m. and stops at 6.30 p.m. with a few minutes rest at midday … seven days a week … The ventilation is inadequate, and the vapour from the low-grade phosphorus damages the lungs. After thirty minutes, my throat was burning. The workers breathe it all day long … On average, 80 fall ill each day. [I also visited] a Beijing textile plant. It employs 15,000 young people. The workers are paid nine [silver] dollars a month for an 18-hour workday, seven days a week. Half are apprentices, who receive no training and are paid no wages, but are simply given food … Their families are too poor to feed them, and are glad to give them to the factory …

In a lodging house I visited, each room, no more than seven feet square, was occupied by 10 workers, half of whom worked by day and half by night. In the whole of that house there was no stove, not a stick of furniture, no fireplace and no lavatory … Nearby, belonging to the same owner, is a sort of windowless cavern with a single door. A group of girls, aged between 10 and 15, sleep there during the day. At night they work in the factory, earning 30 cents a shift. They sleep on a wooden board under a pile of rags. Their biggest worry is that they won't hear the factory siren, and if they arrive late they'll lose their jobs. These people do not live. They exist.36

In Hunan, female and child labour was less common than in the coastal settlements, but otherwise conditions were little different. Until 1920, workers and artisans were organised, as they had been since medieval times, by the traditional trade guilds. But in November of that year two young anarchist students, Huang Ai and Pang Renquan, had established an independent body, the Hunan Workingmen's Association. By the following August, when the Party, at Sneevliet's suggestion, set up a Labour Secretariat under Zhang Guotao, with Mao as head of its Changsha branch, the association had some 2,000 members and had already led a successful strike at the city's Huashi cotton mill.37

Pang was a Xiangtan man, from a village about ten miles from Shaoshan. In September 1921, Mao accompanied him on a visit to the Anyuan coal-mines, part of a big Chinese-owned industrial complex on the border of Hunan and Jiangxi, to see what possibilities might exist for organising the workers there.

He stayed with a distant relative, Mao Ziyun, who worked as a supervisor at the mine. At first his appearance – he wore a traditional blue scholar's gown and carried an oiled-paper umbrella – left the workers perplexed. Despite the May Fourth movement, there was still an almost unbridgeable chasm between mental and manual labour. Gradually, however, the fact that Mao spoke the same dialect and had the same rural origins allowed them to make contact. Exchanging his gown for trousers, he went down into the pits, where he found the miners worked twelve-hour shifts in a temperature of 100 degrees Fahrenheit, naked except for a piece of cloth tied into a turban as protection against head injuries. There was no safety equipment. Gas explosions were common – on average 30 miners died each year – and 90 per cent suffered from hookworm, black lung disease or both.38

This first trip was inconclusive, but in December Mao returned, and shortly afterwards agreed that Li Lisan – who, six years earlier, had sent ‘half a reply’ to his appeal for members for the New People's Study Society – should be based there permanently to establish a school for the workers and their children. Li had studied in France and, on his return, had joined the Party in Shanghai. The non-committal schoolboy Mao remembered had grown into a flamboyant and often impulsive Party militant. Mao advised him to proceed cautiously, first to win the workers’ trust as a teacher, operating, as Li wrote later, ‘under the banner of mass education’, and only later attempting to organize them politically and to set up a Communist Party branch.39

Meanwhile in Changsha in November Mao contributed an article to the Workingmen's Association's newspaper, the Laogong zhoukan (Workingmen's Weekly). ‘The purpose of a labour organisation’, he wrote, ‘is not merely to rally the labourers to get better pay and shorter working hours by means of strikes. It should also nurture class consciousness so as to unite the whole class and seek the basic interests of the class. I hope that every member of the Workingmen's Association will pay special attention to this very basic goal.’40 Soon afterwards, Huang and Pang secretly joined the Socialist Youth League, and in December helped to organise a mass rally, which drew 10,000 people, in protest against manoeuvres by the Powers to extend their economic privileges in China.41 Mao's strategy of co-opting the anarchists, and gradually shifting their focus towards a more Marxist agenda, seemed to be succeeding.

But then, in January 1922, disaster struck. After the New Year holiday, 2,000 workers at the Huashi mill downed tools when the management announced that it was withholding their annual bonus. Equipment and furniture were smashed, and fights broke out with the company police in which three workers were killed. On January 14, Zhao Hengti, who was a major shareholder in the company, declared the strike to be ‘an anti-government act’ and sent in a battalion of troops. After handing out random beatings, they forced the men to resume work by training machine-guns on them. Next day, the 15th, a plea for help was smuggled out. The Workingmen's Association sprang into action. A message came from Governor Zhao asking the two young organisers to come to the mill to negotiate. When they arrived, at nightfall on January 16, they were detained and taken to the Governor's yamen, where Zhao questioned them at length. The workers were granted their bonus. But Huang and Pang were brought to the execution ground by the Liuyang Gate and beheaded, and the Workingmen's Association was banned.42

Their deaths, coming less than three weeks after Zhao had promulgated an ostensibly liberal provincial constitution, enshrining the principle of Hunanese autonomy, sent shock waves across China. Sun Yat-sen urged that Zhao be punished. Cai Yuanpei, at Beijing University, and other eminent Chinese intellectuals, sent telegrams of protest.43 Mao spent most of March and part of April in Shanghai, fanning a virulent campaign against Zhao in the Chinese-language press.44 Even the North China Herald declared the Governor's methods to be ‘inexcusable’.45

On April 1, Zhao issued a long, extremely defensive statement, justifying his conduct:

Unfortunately the general public does not seem to know the correct reasons for the executions, and has mixed them up with matters of the Workingmen's Association in such a way as to bring a charge against me of injuring the association … The two criminals Huang and Pang … [colluded with] certain brigands … in a plot to get arms and ammunition … Their plan was to overturn the government and spread their revolutionary ideas by causing trouble at the time of the Lunar New Year … On me rests the burden of the government of the 30,000,000 people of Hunan. I dare not allow myself to be so confused as to exhibit kindness to merely two men at the peril of the province. Had I not acted as I did, disaster could not have been averted … From the first I have always protected the interests of the workers … I look for Hunan labour to flourish and prosper.46

No one believed these assertions. But, by denying that the executions were linked to the activities of the Workingmen's Association, and explicitly affirming that the pursuit of the workers’ interests was legitimate, Zhao opened the way for the labour movement to resume.

By then Li Lisan's workers’ nightschool at Anyuan was already well-established. Li proved to be a first-rate labour organiser and, in May, persuaded the Anyuan magistrate to authorise the establishment of a ‘Miners' and Railwaymen's Club’ – a covert trade union – which soon boasted its own library, schoolroom and recreation centre. Four months after its inauguration, it had 7,000 members and opened a cooperative store to provide low-interest loans and basic necessities to the workers at substantially lower prices than any of the local merchants.47

All through the spring and summer of 1922, Mao, sometimes accompanied by Yang Kaihui, now pregnant with their first child, travelled to factories and railway depots in Hunan and western Jiangxi – which the Party had placed under the leadership of a newly formed Xiang District Special Committee,48 of which he had been named secretary – to assess the prospects for opening more schools and clubs. The Party Centre in Shanghai had given instructions that labour agitation among railway workers must have top priority. A Railwaymen's Club was established in Changsha, followed in August by one in Yuezhou, on the main line north to Hankou.49

It was at Yuezhou that the trouble began.50

On September 9, a Saturday, groups of workers blocked the line by sitting on the rails, demanding higher wages and modest welfare improvements. Troops were sent to disperse them, killing six workers and seriously injuring many more, together with women and children who had come to support their menfolk. When the news reached Changsha, Mao sent an incendiary telegram to other workers’ groups, seeking their support:

Fellow workers of all the labour groups! Such dark, tyrannical and cruel oppression is visited only on our labouring class. How angry should we be? How bitterly must we hate? How forcefully should we rise up? Take revenge! Fellow workers of the whole country, arise and struggle against the enemy!51

Governor Zhao let it be known that he would stay neutral. Yuezhou was garrisoned by northern troops loyal to Wu Peifu, the head of the Zhili warlord clique in Beijing, whom at this point Zhao viewed as an adversary; any disruption of the rail link to the north could only be to his advantage.52

Word of these events reached Anyuan late on Monday night.53 For some time, trouble had been brewing there over the mining company's refusal to pay back-wages. Now, Mao urged, the moment had come for the Anyuan men to strike too. Drawing on a classical Daoist phrase, he proposed that the guideline for the struggle should be to ‘move the people through righteous indignation’. Li Lisan drew up a list of demands, and forty-eight hours later, at midnight on September 13, the electricity supply to the mineshafts was cut; the mine entrance barricaded with timbers, and a three-cornered flag planted in front of it, bearing the defiant legend: ‘Before we were beasts of burden. Now we are men!’

The miners left two generators running, to prevent the mine flooding. But the following weekend, with negotiations going nowhere, there were calls for them to be switched off. At that, the mine directors capitulated, approving an across-the-board payrise of 50 per cent; union recognition; improved holidays and bonus conditions; the payment of back-wages; and an end to the traditional labour contract system, under which middlemen creamed off for themselves half the annual wage bill. A few days later, more than a thousand delegates from the country's four main rail systems met in Hankou, and threatened a national rail strike unless immediate wage increases were granted. Their demands, too, were met.54

In both the railwaymen's and the miners’ strike, Mao's role was indirect. As CCP Secretary in Hunan, he had guided the strike movement and acted as its political spokesman, but he played no active part in the conflict. A dispute among masons and carpenters, which began a week later in the provincial capital itself, involved him much more closely.55

All through the summer, a row had been simmering in the ancient trade guild of the Temple of Lu Ban, the patron saint of journeymen builders. Their earnings had been eroded by inflation of the paper currency, and in July they asked the Temple Board to persuade the District Magistrate to approve a wage increase.56 But the pressures of the market economy had eroded guild solidarity, too, and contrary to custom, the board insisted that the guild members subscribe 3,000 Chinese silver dollars to finance the negotiation.

‘They went off to all the fancy restaurants, like the Cavern Palace Spring, the Great Hunan and the Meandering Gardens, and held sumptuous banquets,’ one guild member recalled. ‘These bloodsuckers managed to fill their bellies with food and wine, but they didn't come up with a penny for us.’

The stalemate was broken by a man named Ren Shude. The orphaned son of a poor peasant-farmer, he had joined the guild twenty years before as a thirteen-year-old carpenter's apprentice. The previous autumn he had done some work for the Wang Fuzhi Society, helping to get its premises ready for the new Self-Study University. Mao had befriended him, and at the beginning of 1922 he had become one of the first Changsha workers to join the Communist Party.

Ren now proposed that the men go to the Temple and demand an explanation. About 800 did so, but the board's negotiators fled to an inner sanctum, known as the Hall of Five Harmonies, where the workers dared not follow. At his suggestion, a small group then met Mao, whom Ren introduced as a school-teacher involved in the workers’ night-school movement. He advised them to create an independent organisation, with a system of ‘10-man groups’, or cells, like that used by the railwaymen's and miners’ unions. Three weeks later, on September 5, Ren presided over the founding congress of the Changsha Masons’ and Carpenters’ Union, with an initial membership of nearly 1,100 men. Mao himself drafted its charter, and appointed another Party member to act as union secretary.57

For the next month, as the mine and rail strikes unrolled at Anyuan and Yuezhou, Ren and his colleagues carefully laid their plans. Activists surreptitiously handed out pamphlets and, late at night, went to the barracks where, after the officers had retired, they fired arrows with tracts tied to them over the walls, to get the workers’ case across to the soldiers. Mao mobilised the sympathies of liberals within the provincial elite, former associates of Tan Yankai and members of the Hunan autonomy movement. The editor of the Dagongbao, Long Jiangong, inveighed against the very principle of the government regulating wages, noting that there was no comparable restriction on landlords raising rents. ‘In the provincial constitution,’ he wrote, ‘free enterprise is guaranteed. If employers object that [workers’] wages are too high, they should just refuse to hire them. Why do you want to restrict their demands and stop them raising the price of their labour?’

On October 4, the magistrate announced that the wage increase had been rejected.58 Next day, which was a local holiday, the union leaders met at Mao's home at Clearwater Pond, outside the Small East Gate, and resolved to launch a strike for more money, and for the right to free, collective bargaining. This was underlined in the strike declaration that Mao wrote, which was pasted up on walls in the city:

We, the masons and carpenters, wish to inform you that for the sake of earning our livelihood, we demand a modest pay increase … Workers like us, engaged in painful toil, exchange a day of our lives and of our energy for only a few coppers to feed our families. We are not like those idlers who expect to live without working. Look at the merchants! Hardly a day goes by without them raising their prices. Why does no one object to that? Why is it that only we workers, who toil and sweat all day long for a pittance, have to go through such an ordeal of being trampled on? … Even if we cannot enjoy our other rights, we should at least have the freedom to work and to carry out our business. On this point we will make our stand, and go to our deaths if need be. This right we will not surrender.59

The following day, all construction work in the city ceased. The magistrate, supported by the guildmasters, hoped to sit out the dispute. But winter was approaching. The authorities encountered growing public pressure for a rapid end to the strike, so that people could get repairs done to their homes before the cold weather arrived. On October 17, the magistrate appointed a mediation committee, and ordered the strikers to settle quickly: ‘If you refuse to listen, you will be bringing bitterness on yourselves,’ he warned. ‘You should all think long and hard. Do not wait till it's too late and you regret it!’ But the committee's offer, though more generous than earlier proposals, would have ended the traditional craft distinction between older and younger workers’ wages. It, too, was rejected, and the union announced that the workers world march en masse to the magistrate's yamen on Monday, October 23, to deliver a petition. The march was promptly banned, and doubts began to surface among the union leaders. The banning order described them as ‘fomenters of violence’, a term which had last been used to justify the executions of Huang Ai and Pang Renquan in January. By the weekend, the future of the strike was in the balance.

Mao spent much of Sunday night talking to Ren Shude and other members of the union committee. The situation, he argued, was totally different from that of January. Strikes were now occurring in many parts of China, and in this particular dispute, the masons and carpenters had widespread public support. Zhao Hengti had no direct interest in the outcome, as he had had at the Huashi cotton mill, of which he had been a shareholder. Moreover he was now politically isolated, having close relations neither with Sun Yat-sen in the south nor Wu Peifu in the north.

Next morning, almost all the 4,000 masons and carpenters in the city assembled in the square outside the former imperial examination hall, and marched in good order to the District Magistrate's yamen. There they found the main gate blocked by a table. On top of the table were two benches, on which stood a broad arrow, symbol of the military's right to carry out summary executions. Next to it was a board setting out the mediation committee's last offer.60

Mao had marched in the ranks with them, wearing workman's clothes. A union delegation went inside, but emerged some hours later saying that the magistrate refused any concessions. Then a second delegation was admitted. Mao remained outside. At dusk, when extra troops appeared to reinforce the yamen guards, he led the workers in chanting slogans to keep their spirits up. Darkness fell with still no agreement. Supporters brought lanterns, and they prepared to settle in for the night.

The prospect of several thousand angry men on the loose in the centre of Changsha overnight did not please Governor Zhao, who sent a staff officer to try to persuade them to leave. A missionary, who acted as an occasional correspondent for the North China Herald, happened to be on hand:

About 10 p.m. I wandered across to the precincts of the yamen, and found myself just in time to witness a most interesting interview … The staff official … was well-matched in the 10 representatives of the workmen … On both sides there was perfect courtesy. The staff official ‘mistered’ each of the representatives, and used not only the ordinary terms of respect but maintained the bearing of ordinary intercourse among gentlemen. The workmen, while speaking with complete ease and fluency, made no slips in etiquette …

The staff officer mounted a table … After [he had exhorted] the men to return to their homes … one of the ‘ten’, not the acknowledged leader, asked permission to put the officer's suggestion to a vote. ‘Will you go home? Those who are willing to do so, hold up their hand.’ Not a hand was held up. ‘Those who intend to stay holdup their hands.’ Not a hand was wanting. ‘You have your answer,’ was all that the representative commented …

The staff officer … openly admitted not only that the District Magistrate, but that even the Governor, had no right to fix the rate of wages by proclamation without the agreement of both sides … Now and again things became lively; but the workmen paid pretty good attention to the commands for order and silence from their own delegates. After an hour's enjoyment of as well-conducted debate as I have ever listened to, I left the disputants at it. It was 2 a.m. before, tired out and hungry (the soldiers prevented anyone from carrying in either food or clothing), the workmen agreed to go back to their headquarters.61

The ‘acknowledged leader’ whose debating skills so impressed the worthy prelate was Mao. The union representative who called the vote was probably Ren Shude. Before the workers left, they had extracted a promise that talks would resume at the Governor's yamen next morning. For two days more, Mao and the union leaders negotiated with Governor Zhao's deputy, Wu Jinghong. If a businessman could stop selling goods because it was no longer profitable, Mao argued, why could a worker not stop work? If a merchant could raise the price of a product, why could a worker not raise the price of his labour? The right to petition, he noted, was laid down in the provincial constitution. ‘What law, then, are we breaking? Please inform us, honourable Director, sir!’ In the end, the Governor's decision not to use force, and the administration's concern lest the strike trigger civil disorder, left it no way to resist. Director Wu, Mao, Ren Shude and a dozen other union delegates signed an accord, to which the official seal was solemnly affixed, acknowledging that ‘all wage increases are a matter of free contractual relations between labourers and employers’.

With that, the power of the guilds, which had lasted almost unchanged since the Ming dynasty, 500 years earlier, was effectively destroyed in Changsha. The daily rate for the masons and carpenters was raised from 20 to 34 silver cents. It was still ‘not much more than the barest living wage, [on which] no man could support a family of two adults and two children’, the missionary noted.62 But for Mao, for the Party, and for all the city's workers it was a resounding success, and next day some 20,000 of them marched through a cannonade of firecrackers to the yamen to celebrate. ‘Organised Labour's Victory’, the Herald's headline proclaimed:

The government capitulated completely to the express wish of the strikers’ delegates … It is the first encounter of the new form of Workmen's Union with the officials … They gained all they asked; the officials gained nothing in their attempts to compromise. In as much as the workmen's demands were moderate, that is all to the good, but the precedent gives the workmen an enormous power of leverage.63

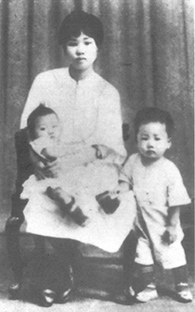

It was not Mao's only triumph that week. While he was negotiating with Director Wu at the Governor's yamen on October 24, Yang Kaihui, who had gone for her confinement to her mother's home in the suburbs, gave birth to a son.64

The strike epidemic spread quickly to other trades. Garment-makers struck twice in September. They were followed by barbers, rickshaw-pullers, dyers and weavers, cobblers, typesetters and writing-brush makers.65 By the beginning of November, when the All-Hunan Federation of Labour Organisations was established, with Mao as its general secretary, fifteen unions had been formed, including the country's first inter-provincial association, the Canton-Hankou General Rail Union, with headquarters at Changsha's main railway station. By the following summer, the number would grow to 22 with 30,000 members. Mao himself served as nominal leader of eight of them.66

In December, as head of the new Federation, he took a joint delegation of union representatives to meet Governor Zhao, the Changsha police chief and other top provincial officials, to discuss the government's intentions in view of the workers’ growing demands. According to Mao's minutes, published afterwards by the Dagongbao, Zhao assured them that constitutional guarantees protecting the right to strike would be maintained, and that his government ‘had no intention of oppressing them’. In reply, Mao explained that what the unions really wanted was socialism, but ‘because this was difficult to achieve in China at present’, their demands would be limited to improvements in wages and working conditions. The Governor agreed that ‘while socialism might be realised in the future, it would be hard to put it into practice today’.

The delegation did not get all it wanted. The administration refused to give an undertaking never to intervene in labour conflicts; nor would it register the Federation as a legally constituted body. But the two sides did agree to have regular contact to ‘avoid misunderstandings’.67

December 1922 marked the peak of the labour movement in Hunan, and a highpoint in Mao's own life. He was Secretary of the provincial Party committee; a highly successful trade union organiser, whom even Governor Zhao had to listen to; and the father of a two-month-old baby boy. On his twenty-ninth birthday, the last of the great wave of strikes he had orchestrated in the province that year, at the Shuikoushan lead and zinc mines near Hengyang, came to a successful conclusion.68

Yet amid the movement's triumphs, there were warning signs as well. Shanghai, the biggest industrial centre of all, was so tightly controlled by an alliance of Western and Chinese capitalists, foreign police and triad labour recruiters, that the Party's Labour Secretariat found it impossible to operate there and in the autumn moved to Beijing.69 Even in Hunan, where the movement was strongest, some prominent sympathisers within the provincial elite were beginning to ask themselves whether the agitation was not going too far.70

In the end it was from Beijing that the fatal blow descended. The Labour Secretariat had gone there partly because the dominant northern leader, Wu Peifu, who early in 1922 had strengthened his position by defeating the Manchurian warlord, Zhang Zuolin, was seen as a relatively liberal figure. Wu liked to play up the contrast between his new government and that of the hated pro-Japanese Anfu clique that had preceded it, and proclaimed that the protection of labour was one of his priorities.71 The communists took note, and that summer the Secretariat and its provincial heads, Mao among them, petitioned the Beijing parliament to enact a labour law providing for an eight-hour workday, paid holidays and maternity leave, and an end to child labour.72 In a separate move, Li Dazhao reached agreement with Wu's officials for six Party members to act as ‘secret inspectors’ on the Beijing–Hankou railway, the main north-south artery for troop movements. Wu's interest was to eliminate Zhang Zuolin's supporters from the railwaymen's labour associations. But the result was that, by the end of the year, most of the railway workforce had been reorganised into communist-led workers’ clubs.

Meanwhile Soviet Russia had sent a new emissary, Adolf Joffe, for fresh talks on the thorny problem of diplomatic recognition. Russian diplomats began to dream of an alliance between Wu and Sun Yat-sen, which would combine northern power with southern revolutionary credentials. But Joffe could not give Beijing what it wanted – the restitution of the Russian-administered Chinese Eastern Railway in Manchuria and an acknowledgement of Chinese interests in Mongolia – and Wu's interest in the Russians and their local protégés waned.73

Against this background, the communist-led railway workers’ clubs on the Beijing–Hankou line called a founding congress, to be held in Zhengzhou on February 1, to establish a General Rail Union, similar to the one Mao had founded in Hunan the previous autumn. A few days before the meeting was to open, Wu Peifu ordered it banned. When the delegates went ahead anyway, troops occupied the union headquarters and a national rail strike was declared. On February 7, 1923, Wu and other warlords cracked down simultaneously in Beijing, Zhengzhou and Hankou. At least forty men were killed, including the branch secretary in Hankou, who was beheaded in front of his comrades on the station platform. More than 200 others were wounded.74

The ‘February Seventh Massacre’, as it became known, punched a huge hole in the communists’ ambitions to use the labour movement as the motor of political change. Work stoppages fell by half, and those that did take place were brutally suppressed. Labour activism was further reduced by rising unemployment as Chinese manufacturers cut back in the face of increased foreign competition.75

In Hunan, where Zhao Hengti was continuing his efforts to keep north and south at arms’ length, the clampdown was initially muted. Mao's Labour Federation sent off angry telegrams, denouncing the ‘unspeakably evil warlords’, led by Wu and his nominal ally, Cao Kun, and warning graphically: ‘Every compatriot who has seen these traitors … regrets that he cannot devour their flesh and make a bed of their skins.’76 The registration of new unions continued and, in March, Mao sent his brothers, Zemin and Zetan, to Anyuan and Shuikoushan to help run the workers’ clubs there. Shortly afterwards Li Lisan left for Wuhan, to be replaced by Liu Shaoqi, a dour, orthodox young Leninist who found it difficult at first to assume the mantle of his charismatic predecessor but was well-placed to continue the cautious reformist policies which Mao had laid down. By then, Anyuan had earned the soubriquet ‘Little Moscow’ and was described by the Party Centre as its ‘great fortress of the proletariat’. After the ‘February Seventh Massacre’, Mao once more underlined the need for restraint, quoting a line from the Tang poet, Han Yu: ‘The drawn bow must await release’.77 He visited the coalmines again in April and then helped to organise a gigantic demonstration in Changsha, which brought 60,000 people onto the streets, as part of a nationwide campaign to demand that Japan return Port Arthur (Lushun) and Dairen (Dalian).78 But that was the last hurrah. Two months later, during a general strike to protest the deaths of two demonstrators killed by marines from a Japanese gunboat, Zhao declared martial law, filled the streets with his troops and issued arrest warrants for union leaders.79

By that point, however, Mao had already left Hunan. In January 1923, Chen Duxiu had invited him to come to Shanghai to work for the Party Central Committee. Li Weihan, three years Mao's junior, a former First Normal student and an early member of the New People's Study Society, was named to succeed him as provincial Party Secretary. The communist rail union leader, Guo Liang, became head of the Labour Federation; and another former New People's Study Society member, twenty-year-old Xia Xi, became secretary of the provincial Youth League. For Mao, it was a substantial promotion. But he was evidently in no hurry to depart, and delayed until mid-April before bidding farewell to Yang Kaihui and his baby son, and boarding the Yangtse steamer which was to take him to the coast.80

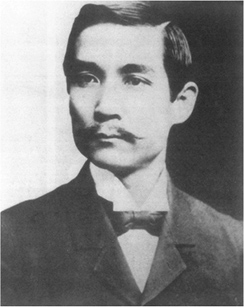

The row between Chen Duxiu and Hendricus Sneevliet, over the Party's relations with Moscow, had been more or less papered over. But a second, much more serious, dispute had arisen over the relationship between the CCP and Sun Yat-sen's Guomindang (GMD). It dated from the winter of 1921, when Sneevliet had met Sun in Guilin. The old revolutionary flummoxed him by declaring that there was ‘nothing new in Marxism. It had all been said 2,000 years ago in the Chinese Classics.’ None the less, Sun's revolutionary credentials, and the Guomindang's effectiveness in supporting the seamen's strike in Hong Kong, which Sneevliet witnessed for himself in Canton, convinced him that a Communist–Guomindang alliance was highly desirable.81

The Chinese comrades strongly disagreed. The Guomindang might be less reactionary than the government in Beijing, but it was still a patriarchal, pre-modern party, with its roots in the secret societies, the dynastic struggle against the Manchus, and the diffuse, shadowy world of literary and intellectual cliques mobilised by the cultured elite. Sun, who was known simply as ‘the Leader’, ran it as a personal fiefdom, requiring his followers to swear an oath of allegiance. It was profoundly corrupt. Its core support was limited to Guangdong and the other southern provinces. It was not, and had no ambition to be, a mass party, capable of mobilising China's workers and peasants, its merchants and industrialists, to struggle against the warlords and imperialists. In Sun's scheme of things, the warlords were not so much enemies as potential partners in future deal-making.

In March 1922, Zhang Guotao, just back from Moscow, where he and Mao's Hunanese colleague, He Shuheng, had attended the Congress of Toilers of the Far East, reported that at a private meeting he held with Lenin, the Soviet leader had been ‘emphatic’ that the communists and the GMD must work together.82 Chen Duxiu's response was to convene a meeting at the beginning of April with Mao, Zhang and members of three other provincial Party branches who happened to be in Shanghai at the time, which ‘passed a unanimous resolution expressing total disapproval’ of any alliance. Afterwards Chen fired off an angry note to Voitinsky, who had become head of the Comintern's Far Eastern Bureau, informing him of this decision, and declaring that the Guomindang's policies were ‘totally incompatible with communism’; that, outside Guangdong, it was regarded as ‘a political party scrambling for power and profit’; and that whatever Sun Yat-sen might say, in practice his movement would not tolerate communist ideas. These factors, Chen concluded, made any accommodation impossible.83

The signatories, Mao included, returned to their home provinces, assuming that that was an end to the matter. However, Sneevliet, knowing that he had Lenin's backing, was not so easily discouraged. Over the next few months, the Party leaders in Shanghai found themselves under conflicting pressures from the Comintern, the Russian government, Guomindang leftists and sympathisers within the Party's own ranks, and from the complex interplay of warlord rivalries. By early summer, when Sun was expelled from Canton in a palace coup by his erstwhile military supporters – and became notably more receptive to the idea of co-operation with Moscow and its allies – the CCP was ready to signal grudging acceptance of the idea of a common front, so long as the GMD changed its ‘vacillating policy’ and took ‘the path of revolutionary struggle’.84

The Second CCP Congress, in July, confirmed the change in policy. A resolution was passed, acknowledging the need for ‘a temporary alliance with the democratic elements to overthrow … our common enemies’.

But the Guomindang was not mentioned by name, and the resolution insisted that ‘under no circumstances’ should the proletariat be placed in a subordinate position. If the communists joined a united front, it was to be for their own benefit, not anyone else's.85 That message was reinforced by the Party's new constitution, which proclaimed its adherence to the Comintern and warned that CCP members could not join any other political party without express authorisation from the Central Committee itself.86 This was slightly less harsh than the policy of ‘exclusion and aggression’ that the First Congress had laid down, but it was hardly extending a welcome to the Guomindang's 50,000 members to join the common cause. Coming from a minuscule political grouping, which at that time, in all of China, had a paid-up membership of 195, it showed astonishing gall.87

Mao did not attend the Second Congress. He claimed later that when he arrived in Shanghai, he ‘forgot the name of the place where it was to be held, could not find any comrades and missed it’. But it seems more likely that he stayed away because he disagreed with the compromise being fashioned.88 If so, he was not alone: the representatives of the Canton Party committee, who were likewise hostile to an alliance with Sun, also failed to attend.89

In August, Sneevliet returned from Moscow, armed with a directive from the Comintern that the Guomindang was to be viewed as a revolutionary party. Two weeks later, at a Central Committee meeting at Hangzhou, he invoked Comintern discipline to ram through, against the vigorous opposition of all the Chinese who attended, a new strategy known as the ‘bloc within’, under which CCP members would join the Guomindang as individuals, and the Party would use the resulting alliance as a vehicle to advance the proletarian cause. Shortly afterwards, a small group of CCP officials, including Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, were inducted into the Guomindang at a ceremony presided over by Sun Yat-sen himself. A new Party weekly, Xiangdao zhoubao (The Guide Weekly), edited by Mao's old friend, Cai Hesen, was set up to promote the alliance, and to try to nudge the Guomindang towards a more revolutionary course. Then, in January 1923, Sun met Adolf Joffe in Shanghai, signalling the start of a closer relationship with Moscow, and – despite reservations from the party's right wing – the first steps were taken towards reorganising the Guomindang on what would eventually be Leninist lines.90

To many communists, however, the ‘bloc within’ strategy remained anathema, and vigorous opposition continued.91

There were other reasons, too, that spring, for the Party leadership to be demoralised. Their one great success, the labour movement, had been smashed. The Party had no legal existence, and was forced to operate underground. Internal divisions had become so acute that, at one point, Chen Duxiu had threatened to resign.92 Sneevliet himself acknowledged that the CCP was an artificial creation, which had been ‘born, or more correctly, fabricated’ before its time, while Joffe had stated publicly that ‘the Soviet system cannot actually be introduced into China, because there do not exist here the conditions for the successful establishment of communism’.93

Even Mao, whose work in Hunan had been singled out for special praise,94 was, according to Sneevliet, ‘at the end of his Latin with labour organisation, and so pessimistic that he saw the only salvation for China in intervention by Russia’. China's future, Mao told him gloomily, would be decided by military power, not by mass organisations, nationalist or communist.95

In this depressed mood, forty delegates, representing 420 Party members, twice as many as the previous year, gathered in Canton for the CCP's Third Congress,96 where once again the relationship with the Guomindang became the dominant issue. The crux of the dispute this time was over Sneevliet's insistence that all Party members should join the Guomindang automatically. Mao, Cai Hesen and the other Hunanese delegates, who voted as a bloc, opposed him.97

Unlike Zhang Guotao, who held that the very principle of collaboration with the Guomindang was wrong, Mao's assessment was pragmatic. After the February incident in Zhengzhou, his thinking about a tactical alliance had changed. The Guomindang, he concluded, represented ‘the main body of the revolutionary democratic faction’, and communists should not be afraid to join it. But the proletariat would grow stronger as China's economy developed, and it was essential that the Party guard its independence so that, when the moment came, it could resume its leading role. The bourgeoisie, Mao argued, was incapable of leading a national revolution; the Comintern's optimism was misplaced:

The Communist Party has temporarily abandoned its most radical views in order to co-operate with the relatively radical Guomindang … in order to overthrow their common enemies … [In the end] the outcome … will be [our] victory … In the immediate future, however, and for a certain period, China will necessarily continue to be the realm of the warlords. Politics will become even darker, the financial situation will become even more chaotic, the armies will further proliferate … [and] the methods for the oppression of the people will become even more terrible … This kind of situation may last for eight to ten years … But if politics becomes more reactionary and more confused, the result will necessarily be to call forth revolutionary ideas among the citizenry of the whole country, and the organisational capacity of the citizens will likewise increase day by day … This situation is … the mother of revolution, it is the magic potion of democracy and independence. Everyone must keep this in mind.98

The prospect of another decade of warlord rule, even leavened by Mao's insistence on the unity of opposites, was too grim for most of his colleagues, and Sneevliet was moved to remark that he did not share his pessimism.99

When the vote was taken, the Comintern line was narrowly approved. But the Party's rank and file, like most of the leadership, remained extremely reserved, and the Congress resolutions were unable to conceal the latent conflicts enshrined in the new policy. The Guomindang, the delegates declared, was to be ‘the central force of the national, revolution and assume its leadership’. Yet, at the same time, the Communist Party, which was assigned the ‘special task’ of mobilising the workers and peasants, was to expand its own ranks at its ally's expense by absorbing ‘truly class-conscious, revolutionary elements’ from the GMD's left wing; while in policy terms its goal was to ‘force the Guomindang’ to move closer to Soviet Russia.100

If the communists were determined to act as a ginger group, the Guomindang was no less determined not to let the tail wag the dog. And so the stage was set for a bruising struggle of wills, and ultimately of arms, which would dominate communist strategy for the rest of the decade and beyond.

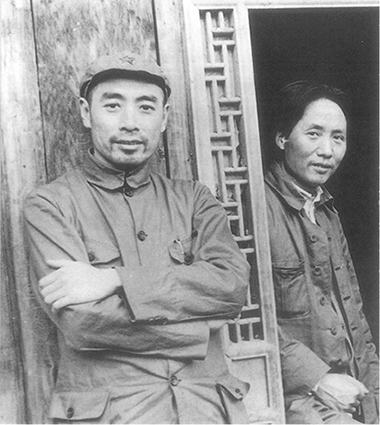

When the Third Congress ended, Mao was elected one of nine members of the Central Committee (CC) and, more significantly, Secretary of the newly established Central Bureau, which was responsible for day-to-day Party affairs,I and comprised himself, the General Secretary, Chen Duxiu, and three others: Mao's fellow Hunanese (and fellow founder members of the New People's Study Society), Cai Hesen and Luo Zhanglong; and the head of the Canton Party committee, Tan Pingshan (soon to be replaced by Wang Hebo, a Shanghainese railwayman and union organiser). Mao was put in charge of personnel work, a key post which made him notionally second only to Chen himself.101

The Party had emerged from its tribulations stronger, more centralised, and more Leninist, at least in the organisational sense, than in its first two years. The struggle to overcome the divisions which had driven Chen Duxiu to threaten resignation the previous autumn had tempered the leadership. Being forced to accept Comintern instructions and to submit to the will of the majority had confronted them for the first time with the principles of democratic centralism on which all Bolshevik parties had to operate. Some, like the Marxist scholar, Li Hanjun, who had argued at the First Congress for a loose-knit, decentralised Party, resigned in disgust. But the outline of an orthodox Party structure was now in place, and Chen Duxiu could no longer complain that ‘the Central Committee internally is not organised … [Its] knowledge is also insufficient … [and its] political viewpoint is not sufficiently clear’.102 Even though the new leadership had no more real grasp of Marxist theory than the old, the basis of a common ideology, guiding and uniting its action, was at last discernible.103

For Mao, these few months in the late spring and summer of 1923 marked a turning-point. At the provincial level, in Hunan, he had been able to influence events as a labour leader and a progressive intellectual with close links to the liberal establishment. Except to a small circle of initiates, his role in the Party had been secret. Now he became a full-time cadre, still operating clandestinely, but with a commanding position in the Party's national leadership. His ties to labour, and to the liberal elite, were abandoned.

Intellectually, too, it was a time for exploring new possibilities. The lesson of the ‘February Seventh Massacre’, that the working class alone could not open the road to power, led him for the first time to consider other options: the military route, which he had discussed with Sneevliet in July and mentioned again, a few weeks later, in a letter to Sun Yat-sen, in which he called for the creation of a ‘centralised national-revolutionary army’;104 and the peasant route, which involved mobilising the most numerous and oppressed sections of China's vast population.

For the time being, however, such thoughts were purely speculative, for the route that the Party had chosen was the ‘united front’. Shortly after the Third Congress, Mao joined the Guomindang.105 He would spend the next year and a half trying to make the front succeed.

In the first weeks, the learning curve was steep for both sides. Sun rejected virtually every proposal the communists made. At a meeting in mid-July, Chen, Mao and the other members of the Central Bureau complained: ‘Nothing can be expected [in terms of] the modernisation of the Guomindang … so long as Sun keeps [to] his [present] notion of [what] a political party [should be], and so long as he does not want to make use of the communist elements [to carry out] the work.’ Sneevliet, as the architect of the front, was especially frustrated. Supporting Sun, he grumbled to Joffe, was simply ‘throwing away money’.106

At the same time, having finally accepted the Comintern's thesis that the way to the future lay through a GMD-led national revolution, the CCP leaders seized on every twitch and whimper that seemed to comfort this strategy. Even Mao, who, a few weeks earlier, had derided the very notion that the bourgeoisie would play a leading role, now lauded the Shanghai business community for supporting the anti-militarist cause:

This revolution is the task of all the people … But … the task that the merchants should shoulder in the national revolution is more urgent and more important than the work that the rest of the Chinese people should take upon themselves … The Shanghai merchants have risen and begun to act … The broader the unity of the merchants, the greater will be their influence, the greater their strength to lead the people of the entire nation, and the more rapid the success of the revolution!107

To some extent this must have been tongue-in-cheek. Mao did not really believe, as he claimed, that of all the Chinese people the merchants suffered ‘most keenly, most urgently’ from warlord and imperialist oppression. Nor did he have much confidence that their new-found revolutionary spirit would last. On the other hand, so long as the warlords were the main enemy, the bourgeoisie had to be an ally. For the moment Mao was ready, like the rest of the Party leadership, to give them the benefit of the doubt.

The key issue remained, however, how to force the Guomindang to change its traditional, elitist ways and become a modern party with a genuine mass base.

At the end of July, after the Central Bureau returned to Shanghai, it was decided to employ a Trojan Horse strategy: Party activists would build up from scratch networks of GMD organisations in northern and central China (where none currently existed), so that these new, communist-dominated regional branches could serve as pressure groups to swing the whole party to the left.108 Li Dazhao was charged with carrying out this mission in north China, and in September Mao went secretly to Changsha to do the same in the central provinces.109

Hunan was once again in the throes of civil war. That summer, one of Zhao Hengti's commanders had mutinied. The former Governor, Tan Yankai, who had been biding his time in the south, where he had established links with Sun Yat-sen, seized the opportunity to invade at the head of a ‘bandit-suppressing army’ bent upon Zhao's overthrow. At the end of August, Tan's allies seized Changsha and Governor Zhao was forced to flee for his life. It was this that persuaded Chen Duxiu to grant Mao leave of absence from his new responsibilities as Secretary, naming Luo Zhanglong to act for him while he was away. Mao was evidently delighted. He did not relish the dry, administrative work which was the Secretary's daily fare. Shanghai, a city created by imperialists and capitalists, would always be foreign to him; and back home in Changsha, Yang Kaihui, whom he had not seen since April, was expecting their second child. But even as he travelled up on the steamer, the tide of warfare turned and when he arrived at Changsha he found it once more in Zhao's hands.110

For the next month, the city was under siege and intermittent bombardment. Tan's allies held the west bank of the Xiang River, Zhao's forces the east. To the foreigners, safe in their consular residences, it seemed ‘an opéra-bouffe war’, with the odd, jagged moment of danger to relieve the tedium. For the Chinese it was very different:

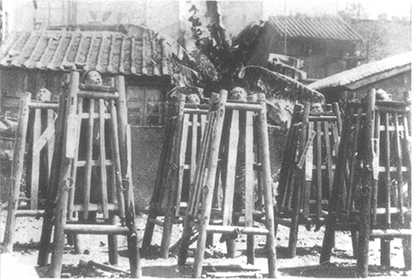

In the city the big shops never took down their night shutters, rich men fled or lay in hiding. All feared the officers who walked or rode through the streets carrying the red paddles [the ‘broad arrows’] of life or death, under the power of which they commandeered rice and money. None dared say nay … [for] those who did … were in danger of being marched to the open space near the Customs House where the executioner stood with a long knife to behead them.111

In the countryside, the villages were subjected to an orgy of rape, plunder and arson reminiscent of the worst days of Zhang Jingyao.112 Mao still thought Tan would win, and wrote to the Guomindang's General Affairs Department in Canton that Zhao would be unable to hold his ground.113 Then, one sunlit morning, came the sound of distant gunfire. Wu Peifu had sent troops to shore up Zhao's support, and Tan's men had been routed. The foreigners watched through binoculars as the victorious force returned, ‘carrying-coolies, machine-guns borne in chairs like invalids, soldiers swinging lanterns and straw shoes, officers shielding themselves from the sun with paper parasols’.114

Zhao's victory came at a price. Hunan's role as a buffer between north and south was at an end. Changsha once more felt the heel of northern soldiers’ boots. The liberal elite allied with Tan, on whose protection Mao had relied, were deprived of power and scattered. On Zhao's orders, the Self-Study University was closed, the Labour Federation and the Students’ Union banned, and a warrant issued for Mao's arrest. Two months earlier he had published a long inventory of Zhao's crimes, describing him as ‘an outrageously and unpardonably wicked creature’. From then on he lived under an assumed name, Mao Shishan (‘Mao the Stone Mountain’).115

There could hardly have been a worse moment to try to launch a nationalist party linked to Zhao's defeated adversary. Mao and the Socialist Youth League leader, Xia Xi, who, on his recommendation had been named the Guomindang's preparatory director in Hunan, were able to establish a provisional Party headquarters for the province, with clandestine branches in Changsha, in Ningxiang (through He Shuheng) and at the Anyuan coalmines, where Liu Shaoqi was still in charge. But they were little more than empty shells, operating in total secrecy.116 Mao remained in Hunan until late December, and celebrated his thirtieth birthday with Yang Kaihui, Anying and their second son, Anqing, born six weeks before.117 That his staying on had more to do with his family than any political commitments is clear from a love-poem he wrote for her soon after his departure, which was evidently marred by a quarrel:

A wave of the hand, and the moment of parting has come.

Harder to bear is facing each other dolefully,

Bitter feelings voiced once more.

Wrath looks out from your eyes and brows,

On the verge of tears, you hold them back.

We know our misunderstandings sprang from that last letter.II

Let it roll away like clouds and mist,

For who in this world is as close as you and I?

Can Heaven fathom our human maladies?

I wonder.

This morning frost lies heavy on the road to East Gate,

The waning moon lights up the pool and half the sky – How cold, how desolate!

One wail of the steam whistle has shattered my heart,

Now I shall roam alone to the furthest ends of the earth.

Let us strive to sever those threads of grief and anger,

Let it be as though the sheer cliffs of Mount Kunlun collapsed,

As though a typhoon swept through the universe.

Let us once again be two birds flying side by side,

Soaring high as the clouds118

While Mao had been in Hunan in the autumn and early winter of 1923, the relationship between the Guomindang and the Russians had undergone a transformation. The Soviet leadership had decided that, given Moscow's international isolation, a progressive Chinese regime, even led by a bourgeois party, would be a valuable ally. Mikhail Borodin, a highly regarded revolutionary who had worked with Lenin and Stalin, was named special envoy to Sun Yat-sen. The Guomindang Chief of Staff, Chiang Kai-shek, a slim, slightly cadaverous man in his mid-thirties, went to Moscow to learn about the Red Army, and was treated royally. Although Sun's quixotic proposal for a Russian-led force to attack Beijing from the north – ‘an adventure doomed in advance to failure’, as the Soviet Revolutionary Military Council put it – was firmly rejected, the Russians agreed to finance a military training school and, at a meeting in November, Trotsky himself promised ‘positive assistance in the form of weapons and economic aid’.

Meanwhile in Canton, Counsellor Bao, as Borodin was called, was deftly working his way around the sensitivities of the two Chinese parties over the triangular alliance Moscow was determined to build.

A thoughtful, patient man, nearly forty years old, Borodin was in many respects the opposite of the domineering Sneevliet. He managed to win Sun's trust while persuading both the Guomindang and the communists that each had most to gain from the new relationship that was being put in place. In October, while Borodin was preparing to help Sun fight off yet another attempt by local warlords to unseat him, the old conspirator cabled Chiang in Moscow: ‘It has now been made entirely clear who are our friends and who are our enemies.’119

On that note, the Guomindang convened its first National Congress in Canton on January 20, 1924. Mao had arrived via Shanghai two weeks earlier with a six-member delegation representing the still largely notional Hunan GMD organisation, including Xia Xi and the provincial CCP leader, Li Weihan.120

The congress approved a new constitution, drawn up by Borodin on Leninist lines, emphasising discipline, centralisation and the need to train revolutionary cadres to mobilise mass support; it adopted a more radical political programme, denouncing imperialism as the root cause of China's sufferings; and it called, for the first time, for the development of workers’ and peasants’ movements to promote the revolution.121 The communists, mostly younger, livelier spirits than the nationalist party veterans, made a strong impression. At one session, Mao and Li Lisan reportedly so dominated the proceedings that the older men ‘looked askance, as if to ask, “Where did those two young unknowns come from?”’ The radical leader, Wang Jingwei, one of Sun's companions from the early days of the Tongmenghui, the Revolutionary Alliance, commented afterwards: ‘The young people of the May Fourth movement are something to be reckoned with, after all. Look at the enthusiasm with which they speak, and their energetic attitude.’122

The new GMD Central Executive Committee (CEC), elected by acclamation on Sun Yat-sen's proposal, included three communists among its twenty-four full members: Li Dazhao; Yu Shude from Beijing; and the Canton CCP leader, Tan Pingshan, who was also named Director of the Organisation Department, one of the most powerful positions in the party, and in that capacity became one of the three members of the CEC's Standing Committee, together with the party Treasurer, Liao Zhongkai, representing the left wing of the Guomindang, and Dai Jitao, representing the right. Mao was appointed one of seventeen alternate (or non-voting) CEC members, seven of whom were communists, including Lin Boqu, a fellow Hunanese who became Director of the GMD Peasant Department; a young literary lion named Qu Qiubai, who had worked in Moscow as correspondent of the progressive Beijing newspaper, Chenbao, and was now Borodin's assistant in Canton; and Zhang Guotao, who had apparently put aside his reservations about the two parties’ unnatural alliance.123

In mid-February Mao moved back to Shanghai, where he shared a house in Zhabei, not far from Bubbling Well Road, in the northern part of the International Settlement, with Luo Zhanglong, Cai Hesen and Cai's girlfriend, Xiang Jingyu.124 For the rest of the year he had a double workload, serving as Secretary for the CCP Central Bureau, which operated from the same address under cover of being a Customs Declaration Office, providing secretarial services for Chinese businesses which had to deal with the foreign-controlled Customs Administration;125 and carrying out similar duties for the Guomindang's Shanghai Executive Committee, with an office in the French concession. The latter was responsible for the work of GMD branches in the four provinces of Anhui, Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, as well as in the city itself.126

This was not the easiest of roles. Despite the best efforts of Borodin in Canton, and of Voitinsky, who was now back in Shanghai as Comintern representative, replacing Hendricus Sneevliet, friction between the two parties intensified. GMD conservatives, not without reason, saw the CCP as a fifth column. In late April or early May 1924, they obtained a copy of a secret Central Committee resolution, ordering communists within the Guomindang to establish a system of tight-knit ‘party fractions’, to transmit and implement Party directives and to prepare for an eventual communist takeover of the party. The right-wing GMD Control Commission began moves to impeach the communist leadership.127 Mao, Cai Hesen and Chen Duxiu argued that the alliance with the GMD had failed and the united front should be broken, but were told by Voitinsky that this was unacceptable to Moscow. The Comintern ordered the resolution annulled, and Sun Yat-sen eventually ruled in favour of maintaining the status quo, but even Borodin grew concerned that an anti-communist coalition was forming which was only deterred from taking action by the fear of losing Russian aid.128

In July, Chen and Mao issued a secret Central Committee circular, reaffirming the ‘bloc within’ strategy laid down by the Third Congress a year earlier, but noting that it was proving ‘extremely difficult’ to carry out: