CHAPTER SEVEN

Out of the Barrel of a Gun

Besso Lominadze did not hit it off with his Chinese charges. He was young, inexperienced, knew little about the world beyond the Soviet Union's borders and appeared to care less. Zhang Guotao remembered meeting him the day he arrived in Wuhan, July 23. It was, he wrote later, ‘the worst conversation in my memory … His character seemed to be that of a spiv after the October Revolution, while his attitude was that of an inspector-general of the Czar … [treating] the intellectuals of the CCP … as serfs.’1

Besso Lominadze was Stalin's man. At the age of twenty-eight, he had been sent to ram down the throats of the Chinese leaders the Comintern's new line, and to ensure that they, not Stalin, were blamed for the egregious failures of the recent past. To Lominadze, Moscow was the fount of all possible wisdom. He came, in Zhang's words, bearing ‘an imperial edict’: all that the vacillating, petty-bourgeois leaders of the Chinese Party had to do was to apply Soviet experience and Comintern directives correctly and the Chinese revolution would triumph, to the greater glory of Russia and those who ruled it. Unlike Borodin, who had spent a lifetime subtly fomenting revolution abroad, or Roy, who had debated agrarian policy with Lenin, Lominadze and the small group of arrogant and insecure young men who came to China with him were simply cogs in Stalin's personal power machine.2 In the second half of 1927, the master of the Kremlin was far less concerned with the future of the Chinese revolution than with being able to show that Trotsky's views were wrong and his own, correct.

The Chinese communists were by this time just starting to pull themselves together after Chen Duxiu's enforced resignation and the united front's collapse.3 The massacre of Party cadres that had begun in Jiangxi in March, accelerated in Shanghai in April and reached its zenith in Hunan in May, was now seen clearly for what it was: the fate of a parasite party which, when its host organism turns against it, has neither the means nor the will for self-defence. Very quickly, therefore, after the July 15 break with the Guomindang, the CCP's new provisional leadership, basing itself on Stalin's order to build a communist-led peasant army, began to sketch out guidelines for an independent strategy.

On July 20, a secret directive on peasant movement tactics, which Mao almost certainly helped to draft, asserted that ‘only if there is a revolutionary armed force can victory be assured in the struggle of the peasants’ associations for political power’, and called on association cadres to give ‘120 per cent of [their] attention to this issue’. It went on to discuss in detail the different means the Party could use to assemble such a force. These included seizing weapons from landlord militias; sending ‘brave and trained members of the peasants’ associations’ to act as a fifth column inside the warlord armies; forming alliances with secret society members; the clandestine training of peasant self-defence forces; and, if all else failed, then, as Mao and Cai Hesen had urged two weeks earlier, ‘going up the mountains’.4

At the same time, the Politburo Standing Committee began preparing for a wave of peasant insurrections in Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi and Guangdong, to be staged during the Autumn Harvest Festival in mid-September, when land rents fell due and seasonal tensions between peasants and landlords would be greatest,5 and for a military uprising in Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi, where several communist-officered units in the Guomindang's National Revolutionary Army were based.6

Moscow knew nothing of these plans, and when consulted by an anxious Lominadze, who had no desire to be crucified for yet another débâcle, responded with a delphic double negative: ‘If the uprising has no hope of victory, it would be better not to start it.’7 But by then the Chinese leaders had had enough of the Comintern's studied ambiguities. After the long months of humiliating retreat under Borodin and Chen Duxiu, they were determined to act at almost any price. Ignoring Moscow's reservations, Zhou Enlai, at the head of a specially constituted Front Committee,I ordered the insurrection to commence in the early hours of August 1. Nanchang fell with hardly a shot fired and remained in communist hands for four days – delighting Stalin, for whom it provided a victory to flaunt before the Trotskyist opposition.8

The list of participants read like the Almanac de Gotha of the Communist revolution. Zhu De, afterwards the Red Army's Commander-in-Chief, was Chief of Public Security in Nanchang. He Long, a moustachioed Sichuanese with a colourful history of secret society allegiance, later a communist marshal, commanded the main insurrectionary force. Ye Ting, then a divisional commander, would go on to head the communist New Fourth Army during the war with Japan. Ye's Political Commissar, Nie Rongzhen, and Chief of Staff, Ye Jianying, were also future marshals. So was one of the youngest officers to take part, a slim, rather shy graduate of the Whampoa Military Academy named Lin Biao. He had just turned twenty.II

The communist force, some 20,000 strong, left Nanchang on August 5, heading south, where they hoped, as a communist-inspired proclamation put it, to establish ‘a new base area … outside the spheres of the old and new warlords’, in Guangdong.9

While these events were unfolding, Mao remained in Wuhan, where, on the Comintern's instructions, Qu Qiubai and Lominadze, helped by a young member of the Secretariat named Deng Xixian, subsequently better known by his nom de guerre, Deng Xiaoping, were preparing an emergency Party conference. Its declared purpose was to ‘reorganise [the Party's] forces, correct the serious mistakes of the past, and find a new path’.10

Two days later, twenty-two CCP members, all men, gathered in the apartment of a Russian economic adviser on the upper floor of a large European-style house in the consular district in Hankou. They were told not to leave while the conference was in progress, for fear of attracting unwelcome attention, and to say, should anyone come to the door, that they were holding a shareholders’ meeting.11 Qu was dressed incongruously in a loud flannel shirt. He was ravaged by tuberculosis, and the swollen veins on his face stood out in the suffocating August heat.12 Because of the haste with which the conference had been organised, the need for secrecy and the absence of many leaders in Nanchang, fewer than a third of the Central Committee attended, which, under Party rules, fell short of a quorum. But Lominadze insisted that, in the emergency the Party was now facing, the meeting could take interim decisions, which would be ratified by a congress to be held within the next six months.13

The new strategy which the August 7 Conference endorsed reflected Stalin's instructions of the previous winter and spring, in which he had laid down that there was no contradiction between class struggle against the landlords and national revolution against the warlord regime. The revolution's centre of gravity, Lominadze argued, should shift to the labour unions and the peasant associations; peasants and workers should play a greater role in the Party's leading organs; and a co-ordinated strategy should be developed of armed workers’ and peasants’ insurrections. In this respect, he said, the Nanchang uprising marked ‘a clear turning-point’. The old, irresolute policy of compromise and concessions, followed by the outgoing leadership of Chen Duxiu, had been abandoned.

Lominadze hammered home two other lessons from Moscow. The Comintern's instructions must always be obeyed: by rejecting its guidance in June, the Party leadership had committed not just a breach of discipline but ‘a criminal act’. And since the Party could no longer function openly, even in GMD-ruled areas, it must be refashioned into a militant, clandestine organisation with ‘solid, combative secret organs’.14

Ostensibly to unify thinking, but equally to save Stalin's face, the conference issued a ‘Circular Letter to All Party Members’, containing a lengthy self-criticism which left few of the former leaders unscathed. Chen Duxiu, whom Lominadze (like Roy) charged with Menshevism,III was denounced by name for ‘standing the revolution on its head’, restraining the peasant and labour movements, kowtowing to the Guomindang and abandoning the Party's independence. Tan Pingshan was castigated for his conduct as GMD Minister for Peasant Affairs, when he allegedly ‘abandoned the struggle’ and ‘shamefully … refused to support the rural revolution’. Li Weihan, though not named, was blamed for countermanding the peasants’ attack on Changsha in late May, and Zhou Enlai was reproached for having approved the disarming of workers’ pickets in Wuhan in June. Even Mao was implicitly criticised for having omitted to protest against the GMD's failure to implement land redistribution, and for not having taken a radical enough line in the directives he had drafted for the All-China Peasants’ Association.15

None the less, he found the new team of Lominadze and Qu Qiubai much more to his liking than the Borodin–Chen Duxiu leadership it had replaced. Their explicit stress on class struggle, on the primacy of the peasants and workers as the main engine of revolt, and on the use of armed force, was music to his ears. He also approved of the connection which Lominadze drew between imperialism abroad and feudalism at home.16

Lominadze, in turn, found Mao ‘a capable comrade’, and when the new provisional leadership was announced, he was rewarded by being made a Politburo alternate (returning to that body for the first time since his withdrawal to Shaoshan in January 1925).17 Of the nine full members of the Politburo, four were new appointees with working-class backgrounds, one of whom, Su Zhaozheng, was named to the three-man Standing Committee, together with Qu Qiubai and Li Weihan, in line with Lominadze's insistence that workers play a larger role. Peng Pai, who was with the Nanchang rebels, represented the peasant movement, and Ren Bishi, the Youth League. Zhang Guotao and Cai Hesen, both regarded as moderates, were demoted. Zhang hung on for a few months as an alternate member, while Cai, who had been part of the top leadership since 1922, left to become Secretary of the CCP Northern Bureau.18

Why was Peng Pai, rather than Mao, chosen for full Politburo membership as peasant movement representative? One factor may have been the leadership's hopes of re-establishing a strong base in Guangdong, Peng Pai's home territory. But there was also the problem of Mao's character. He was unconformable. Immediately after Chen Duxiu's fall, Zhou Enlai had tried unsuccessfully to reassign him to Sichuan, partly, it seems, to detach him from his Hunan power base.19 Qu, who had worked with him on the Peasant Committee earlier in the year, had had plenty of opportunity to observe how headstrong and stubborn he could be: a good man to have as an ally – but not as a rival, or a subordinate to try to control.20

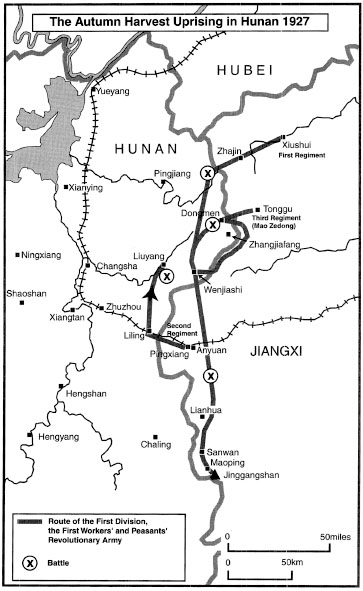

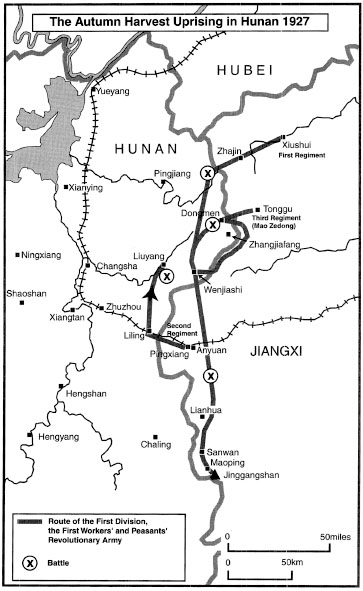

Shortly before Lominadze's arrival, Mao had been given responsibility for planning the Autumn Harvest Uprising in Hunan. His first proposal, approved by the Standing Committee on August 1, envisaged the creation of a peasant army, comprising a regiment of regular soldiers from Nanchang, and two regiments, each of about a thousand peasant self-defence force troops, from eastern and southern Hunan. They were to occupy five or six counties in the south of the province, promote agrarian revolution and set up a revolutionary district government. The aim was to destabilise the rule of Tang Shengzhi and He Jian and create ‘centres of revolutionary force’ from which a province-wide peasant uprising would be launched to overthrow them.21

On August 3, the Standing Committee incorporated this plan into its outline for the full four-province Autumn Harvest Uprising, now defined as an ‘anti-rent and anti-tax’ revolt, which it hoped would ultimately lead to the formation of a new revolutionary government covering both Hunan and Guangdong.22

The success of the Nanchang uprising, however, persuaded Qu and Lominadze that the action in Hunan should not be limited to the south but should cover the entire province. Two days later, a revised plan was sought from the Hunan Party committee.

Apparently it was unsatisfactory, for on August 9, Lominadze, acting on advice from the new Soviet consul (and Comintern agent) in Changsha, Vladimir Kuchumov, who had accompanied him from Moscow and used the alias Mayer, declared that the committee – headed by Yi Lirong, Mao's old friend and a former New People's Study Society colleague – was incompetent and needed to be reorganised.23 To Mao's credit, when this issue was raised before the Politburo, he defended Yi and his team, arguing that they had been trying courageously ‘to pick up the pieces in the tragic situation after the [Horse Day Incident]’. But to no avail. Lominadze named another Hunanese, Peng Gongda, who was a Politburo alternate, to be the new provincial Party Secretary.24

On August 12 Mao was appointed Central Committee Special Commissioner for Hunan, and set out for Changsha to begin preparing to get the uprising under way.25 A week later the new, ‘reorganised’ Hunan Party committee, which included, as Lominadze had instructed, ‘a majority of comrades with worker-peasant backgrounds’, held its first meeting, in the presence of Kuchumov, at a house in the countryside near Changsha, to discuss its plan of campaign.

At this point, three problems emerged. The first was relatively minor. Kuchumov briefed the meeting on the latest messages from Hankou, transmitted while Mao was en route, and either he or Mao, or both, concluded – mistakenly, as it turned out – that Stalin had at last authorised the setting-up of worker-peasant soviets on the Russian model as organs of local power. Mao was ecstatic, and wrote to the Central Committee at once:

On hearing this, I jumped for joy. Objectively speaking, the situation in China has long since reached 1917, but formerly everyone held that we were in 1905. This has been an extremely great error. Soviets of workers, peasants and soldiers are wholly adapted to the objective situation … As soon as [their power] is established [in Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi and Guangdong], [it] should rapidly achieve victory in the whole country.26

It followed, he argued, that the time had come for the Party to act in its own name, rather than maintaining the pretence of being in a revolutionary alliance with progressive elements of the discredited GMD. ‘The Guomindang banner has become the banner of the warlords,’ Mao wrote. ‘[It] is already nothing but a black flag, and we must immediately and resolutely raise the Red flag.’

In a province where the peasantry associated the Guomindang emblem, a white sun on a blue ground, with the terrible massacres perpetrated by Xu Kexiang, this was no more than common sense.27 But the issue was politically sensitive because it had become enmeshed in the ongoing dispute between Stalin and Trotsky. In the event, Mao was four weeks ahead of the game. The setting-up of soviets, and the abandonment of the Guomindang flag, were finally approved a month later. In Stalin's Russian paradigm, it was indeed 1917, as Mao claimed, but April, not October.28

The second problem had to do with the perennial question of land confiscation. The August 7 Conference had skirted round this issue.29 Mao had spent several days, after his return to Changsha, canvassing peasant views. He now put forward a far-reaching proposal, which sought to reconcile the Party's policy of ‘land nationalisation’ and the land hunger of the poor. ‘All the land,’ he told the provincial committee, ‘including that of small landlords and owner-peasants … [should be taken] into public ownership’ and redistributed ‘fairly’ (a demand for which, afterwards, endless ink and blood would be spilled) on the basis of each family's labour power and the number of mouths it had to feed. Small landlords and their dependents (but not big landlords) should be included in the share-out, he added, ‘for only thus can the people's minds be set at ease’.30

The question of definitions was of more than passing interest. It was to be the anvil on which argument about land reform, the very core of the Chinese communist revolution, would be hammered out ceaselessly right up to the eve of victory in 1949.

In August 1927, however, Mao's proposals were more radical then even Qu Qiubai's Politburo was ready to accept. In a detailed reply sent off on August 23, the Party Centre told him that, while not wrong in principle, on this issue – as on the question of forming soviets, and not using the GMD flag – he was, at the least, premature. Confiscating small landlord holdings was bound to occur at some point, it declared; but to raise it as a slogan immediately was tactically unwise.31

The third problem to emerge from the debates in Changsha was still more fundamental, and far less easily disposed of, for it went to the heart of the entire strategy of armed insurrection on which Qu Qiubai and his colleagues were counting to revive the communist cause. Since Stalin's telegram in June, a broad consensus had developed that, to carry forward the revolution, the Party would have to use armed force. But that was as far as the analysis went. Such questions as the form this force would take; the role it should play; how it might be combined with the peasant and worker mass movements and how it should be harnessed to promote the Party's political power, had not been addressed at all. Mao had set out the issue succinctly on August 7 in Hankou:

We used to censure [Sun] Yat-sen for engaging only in a military movement, and we did just the opposite, not undertaking a military movement, but exclusively a mass movement. Both Chiang [Kai-shek] and Tang [Q1][Shengzhi] rose by grasping the gun; we alone did not concern ourselves with this. At present though we have paid some attention to it, we still have no firm concept about it. The Autumn Harvest Uprising, for example, is simply impossible without military force … From now on we should pay the greatest attention to military affairs. We must know that political power is obtained out of the barrel of a gun.32

At the time, nobody objected to this memorable formulation. Lominadze himself acknowledged that the Nanchang insurrection had put army units at the Party's disposal which would help ‘assure the success’ of the Autumn Harvest Uprising.33 Very quickly, however, that judgement was revised. The Hunanese leaders were warned against ‘putting the cart before the horse’. Popular insurrection must come first, the Politburo ruled; military force, second. Mao's dictum about political power – ‘gun-barrel-ism’, as it would later be called – was viewed more sceptically. It ‘did not quite accord’ with the opinion of the Centre, the Standing Committee decided ten days later. The masses were the core of the revolution; the armed forces, at most, auxiliary.34

For young Chinese radicals in the 1920s, this was no idle debate. Throughout the last decade, China had been devastated by men for whom political and every other kind of power grew from the barrel of a gun: the warlords. How a political force could control a military one was a burning issue, made fiercer by the communists’ recent experience with the Guomindang, whose civilian leadership had signally failed to master its own generals. Added to that was the insurrectionary myth of 1917, which held that popular uprisings were somehow more ‘revolutionary’ than military conquest; that military power could be used to defend revolutionary gains, but the initial spark must come from the peasants and workers themselves throwing off their chains. Moreover, Qu Qiubai maintained, this was precisely what the peasants were waiting for: all the Party had to do was ‘light the fuse’, and unquenchable rural revolution would explode across southern China.35

The provincial leaders charged with carrying out the insurrection knew better. Local Party officials in Hubei sent in a steady stream of discouraging reports about peasant demoralisation. In Hunan, one committee member said bluntly that the peasants had no stomach for a fight; all they wanted was good government, whatever its political complexion. Mao agreed. Had the communists acted in the spring, the situation would have been different. But after three months in which their rural networks had been driven underground or dismantled, and the peasants had been bludgeoned into submission through a general blood-letting of appalling ferocity, to stage uprisings without military support was to court disaster. ‘With the help of one or two regiments, the uprising can take place,’ Mao warned. ‘Otherwise it will inevitably fail … To [think otherwise] is sheer self-deception.’36

Unsurprisingly, given this divergence of views. Mao's revised plan, which was presented to the Standing Committee in Wuhan on August 22, fell far short of the Centre's expectations.

In his written proposals, he tried to disguise his intentions, assuring his Politburo colleagues that although the uprising would need to be ‘kindled’ by two regiments of regular troops, the workers and peasants would be ‘the main force’; that while it would ‘start’ in Changsha, ‘southern and western Hunan would rise up simultaneously’; and that ‘if by any chance it should prove impossible to take [all of] southern Hunan at present’, a fall-back plan was in place for an uprising in just three southern counties.37 But either they saw through him, or the young provincial committee member who had brought the Hunan documents to Wuhan, along with a verbal proposal that the uprising begin on August 30 – ten days earlier than planned – spilled the beans. In any event, the plan was rejected. Changsha was a legitimate starting-point, the Standing Committee acknowledged, but:

First, both your written report and the verbal report … reveal that your preparations for a peasant uprising in the [surrounding] counties are extremely feeble, and that you are relying on outside military force to seize Changsha. This sort of one-sided emphasis on military strength makes it appear that you have no faith in the revolutionary strength of the masses. This can only lead to military adventurism. Secondly, in your preoccupation with Changsha work, you have neglected the Autumn Harvest Uprising in other areas – for example, your abandonment of the plan for south Hunan … Furthermore, as events have turned out, you will not have two regiments [of regular troops] at your disposal [because they will not be available].38

The Politburo's reading of Mao's intentions was absolutely correct. He had indeed abandoned the idea of a province-wide uprising, being convinced that the whole venture would fail unless all available forces were concentrated on Changsha.39 The news that regular troops would not after all be available for the attack on the provincial capital merely strengthened that conviction. In Hubei, the provincial leadership, faced with a similar dilemma, bent reluctantly to the Centre's will.40 Mao, who had seen the Chen Duxiu leadership wrongly reject his views on the peasant movement in the spring, was not about to yield in the autumn to what he saw as the wrong views of Qu Qiubai. After a week spent bolstering the courage of the provincial committee, including a reluctant Peng Gongda, he penned a robust reply – stating in effect that Hunan would do as it saw fit – and despatched the unfortunate Peng to deliver it:

With regard to the two mistakes pointed out in [your] letter, neither facts nor theory are at all compatible with what you say … The purpose in deploying two regiments in the attack on Changsha is to compensate for the insufficiency of the worker-peasant forces. They are not the main force. They will serve to shield the development of the uprising … When you say that we are engaging in military adventurism … this truly reflects a lack of understanding of the situation here, and constitutes a contradictory policy which pays no attention to military affairs while at the same time calling for an armed uprising of the popular masses.

You say that we pay attention only to the work in Changsha and neglect other places. This is absolutely untrue … [The point is that] our force is sufficient only for an uprising in central Hunan. If we launched an uprising in every county, our force would be dispersed and [then] even the [Changsha] uprising could not be carried out.41

No record has survived of the Standing Committee discussion when Peng arrived with this message of defiance. But on September 5, the Party Centre gave vent to its frustration in an angry counterblast:

The Hunan Provincial Committee … has missed a number of opportunities for furthering insurrection among the peasantry. It must [now] at once act resolutely in accordance with the Central plan, and build the main force of the uprising on the peasants themselves. No wavering will be permitted … In the midst of this critical struggle the Centre instructs the Hunan Provincial Committee to implement Central resolutions absolutely. No wavering will be permitted.42

By then, however, as the Standing Committee well knew, this was too late to have the slightest effect. The ‘Central plan’ it spoke of, which had been sent to Changsha a few days earlier, had laid out an even more elaborate programme, drawn up by Qu Qiubai, for a general insurrection in which co-ordinated popular uprisings, carried out in the name of a so-called ‘Hunan and Hubei Sub-Committee of the Revolutionary Committee of China’, would lead to the capture, first of county towns, then of provincial capitals, and finally the whole of China.43 To Mao, it bore no relation to the available resources, and he simply ignored it.44

While Peng was in Wuhan, he left for Anyuan, where he established a Front Committee and began gathering his forces for the assault on Changsha, the centre-piece of the limited action the provincial Party committee had approved.45

These comprised a regiment of about a thousand regular troops, formerly part of the GMD's National Revolutionary Army (renamed by Mao the 1st Regiment), which had defected to the communists and was now based at Xiushui, near the Jiangxi–Hubei border, 120 miles north-east of Changsha; a poorly armed peasant force (the 3rd Regiment), at Tonggu, a small town in the mountains on the Jiangxi–Hunan border; and, at Anyuan itself, a mixed unit of about a thousand unemployed miners (who had lost their jobs when the labour movement was crushed in 1925), and members of the local West Jiangxi Peasant Self-Defence Force (the 2nd Regiment). Together they made up the 1st Division of what the Politburo had agreed should be called the 1st Workers’ and Peasants’ Revolutionary Army.46

By September 8, the timetable for the insurrection had reached the different units (and had also, unknown to Mao, been betrayed to the Changsha authorities). At his orders, the Guomindang banner was discarded. Local tailors in Xiushui worked through the night making what the troops called ‘axe and sickle’ flags, the first ever carried by a Chinese communist army. Next day, the railway lines to Changsha were sabotaged and the 1st Regiment set out for Pingjiang, fifty miles north-east of the capital.47

At that point an event occurred which might have changed not just the course of the uprising but the future of China. As Mao and a companion were travelling from Anyuan to Tonggu, they were captured by Guomindang militiamen near the mountain village of Zhangjiafang:

The Guomindang terror was then at its height and hundreds of suspected Reds were being shot [Mao recalled years later], I was ordered to be taken to the militia headquarters, where I was to be killed. Borrowing several tens of dollars from [my] comrade, however, I attempted to bribe the escort to free me. The ordinary soldiers were mercenaries, with no special interest in seeing me killed, and they agreed to release me. But the subaltern in charge refused to permit it. I therefore decided to attempt to escape, but I had no opportunity to do so until I was within about 200 yards of the militia headquarters. At that point I broke loose and ran into the fields.

I reached a high place, above a pond, with some tall grass surrounding it, and there I hid until sunset. The soldiers pursued me, and forced some peasants to help them search. Many times they came very near, once or twice so close that I could almost have touched them, but somehow I escaped discovery, although half-a-dozen times I gave up hope, feeling certain I would be recaptured. At last, when it was dusk, they abandoned the search. At once I set off across the mountains, travelling all night. I had no shoes and my feet were badly bruised. On the road I met a peasant who befriended me, gave me shelter and later guided me to the next district. I had seven dollars with me, and used this to buy some shoes, an umbrella and food. When at last I reached [Tonggu] safely, I had only two copper [cash] in my pocket.48

This episode seemed to exhaust whatever good luck Mao had left. The 1st Regiment marched into an ambush set by a local force which coveted its superior weapons, and two of its three battalions were wiped out. The following day, September 12, Mao's 3rd Regiment occupied the small town of Dongmen, ten miles inside the Hunan border. But there the advance stalled. Provincial government troops counter-attacked, and the insurgents were driven back into Jiangxi where, two days later, Mao learned of the disaster that had befallen the 1st Regiment. That night he sent a message to the provincial committee, recommending that the workers’ insurrection which was to have been launched in Changsha on the morning of September 16 be called off.

Next day, Peng Gongda endorsed his proposal, and to all intents and purposes the uprising was over. There was still one last piece of bad news to come. The 2nd (Anyuan) Regiment, after seizing Liling, a small county seat on the railway line, just inside the provincial border, proceeded as planned to Liuyang to await Mao's forces. When they failed to appear, it attacked alone on September 16 but was repulsed. The following day the regiment was surrounded and wiped out to the last man.

The failure could hardly have been more complete.

Of the 3,000 men who had started out eight days earlier, only half remained, the rest lost through desertion, treachery or combat. Mao himself had been captured and barely escaped with his life. The insurgents had managed to occupy two or three small towns along the provincial border, but none for more than twenty-four hours. Changsha itself had never been remotely threatened.49

For three days, they argued over what to do next. Yu Sadu, the 1st Regiment's deputy commander, wanted to regroup and make a fresh attempt to seize Liuyang. But Mao and Lu Deming, the most experienced military officer in the force, disagreed. Early in August, when Qu Qiubai's newly elected Politburo had met for the first time in Wuhan, Mao had told Lominadze that if the insurrection in Hunan were defeated, the surviving forces ‘should go up the mountains’. On September 19, the Front Committee, after an all-night meeting in the border village of Wenjiashi, approved this course. Next day, Mao called a meeting of the whole army outside the local school, where he announced that the attack on Changsha was being abandoned.IV The struggle, he told them, was not over. But at this stage their place was not in the city. They needed to find a new rural base where the enemy was weaker. On September 21, they set out, heading south.50

In Hubei and elsewhere, the uprisings were equally unsuccessful. The insurrectionary army that left Nanchang lost 13,000 of its 21,000 men in two weeks, mostly through desertion. By the time the survivors reached the coast, their spirit had been broken. At the beginning of October, most of the leaders, including He Long, Ye Ting, Zhang Guotao and Zhou Enlai (who by then had to be carried on a stretcher), made their way to a fishing village, ‘hired boats and simply fled to Hong Kong’ – even in those days a refuge for rebellious Chinese.51 The expedition, Zhang acknowledged later, was ‘politically and militarily very juvenile’ and had pitiful results.52 Only two small military units survived more or less intact: one linked up with Peng Pai's forces in Hailufeng; the other, under Zhu De and his young deputy, Chen Yi, reached an accommodation with a local warlord and based itself in northern Guangdong.53

In November, the Politburo met in Shanghai to take stock. The Party's ‘general line’ and insurrectionary strategy, it declared, had been ‘entirely correct’. The uprisings had failed only because they had been carried out from ‘a purely military viewpoint’ and insufficient attention had been paid to mobilising the masses.

Punishments were then announced. The Hunan leaders were held to have relied excessively on ‘local bandits and a handful of motley troops’. At Lominadze's insistence, Mao was dismissed from the Politburo, although he was apparently allowed to retain his membership of the Central Committee. Peng, whom the Comintern's Changsha agent, Kuchumov, accused of ‘cowardice and deception’, lost all his posts and was only allowed to remain in the Party ‘on probation’. Blame for the collapse of the Nanchang forces was attributed to Zhang Guotao, who was also removed from the Politburo, and to Tan Pingshan, the Chairman of the Nanchang Revolutionary Committee, who was expelled from the Party. Zhou Enlai and Li Lisan were let off with reprimands.54

It was the Chinese leaders’ first experience of Bolshevik discipline, Stalinist-style.

Because the basic policy was held to be correct, these decisions paved the way for another round of doomed uprisings, which reached its climax in Canton in December. There the insurrectionist forces, backed by 1,200 cadets from a Guomindang officers’ training unit, commanded by Ye Jianying, held out for nearly three days. But in the massacre that followed, thousands of Party-members and sympathisers were killed. To save bullets, groups of them were roped together, taken out to sea on barges and thrown overboard. Five Soviet officials at the consulate were put up against a wall and shot. Soon afterwards, all Soviet missions in China were ordered to close.55

Yet even this was not enough to deter the Politburo. In a year which had seen Party membership collapse from 57,000 in May to 10,000 by December, each new setback became cause to stoke still higher the fires of militancy and revolutionary ardour. Stalinists like Lominadze, Kuchumov in Changsha and Heinz Neumann in Canton, added fuel to the flames. But the underlying reason was frustration with the failed alliance with the Guomindang, which caught up the Party's leaders and rank and file alike in a furious spiral of ever-increasing radicalisation.

The following spring, all that remained from this explosion of pent-up revolutionary fervour were a few isolated communist hold-outs in the poorest and most inaccessible regions, many of them situated along the fault-lines where two or more provinces met and the authorities’ writ did not run: in northern Guangdong; on the Hunan–Jiangxi border; in north-eastern Jiangxi; on the Hunan–Hubei border; in the Hubei–Henan–Anhui border triangle; and on Hainan Island in the far south.56

For the next three years, the politics of the Chinese Communist Party would be forged through a quadrilateral struggle between Moscow, the Politburo in Shanghai, the provincial Party committees, and the communist military leaders in the field, over two key issues: the relationship between rural and urban revolution; and between insurrection and armed struggle.

Mao would play a key role in these crucial debates. But in the autumn of 1927, his immediate concern was survival.

On September 25, four days after setting out from Wenjiashi, his little army was attacked in the hill country south of Pingxiang. The divisional commander, Lu Deming, was killed. The 3rd Regiment was scattered, and two or three hundred peasant troops and a quantity of equipment were lost. The remainder regrouped in the mountain village of Sanwan, twenty-five miles north of the massif of Jinggangshan.

There Mao reorganised his forces, consolidating the remnants of the division into a single regiment – the ‘1st Regiment, 1st Division, of the First Workers’ and Peasants’ Revolutionary Army’ – and appointing political commissars, modelled on the system which General Blyukher's Soviet military advisers had developed for the GMD army, based on Russian practice. Each squad had its Party group; each company, a Party branch; and each battalion, a Party committee.57 All were under the leadership of the Front Committee, of which Mao remained Secretary.

But the originality of the changes made at Sanwan lay elsewhere. Most of Mao's previous experience had been as a political theorist. His only direct exposure to mass struggle had been as a labour organiser in Changsha, and as an observer of the Hunan peasant movement. Now, for the first time in his life, he found himself having to motivate and lead a ragged, undisciplined band of some 700 Guomindang mutineers, armed workers and peasants, vagabonds and bandits, which somehow had to be transformed into a coherent revolutionary force capable of resisting a vastly superior enemy.

To that end, he announced two policies which laid the basis for a very different army from any other existing in China at that time. In the first place, it was to be an all-volunteer force. Any man who wished to leave, Mao told them, was free to do so and would be given money for the journey. Those who stayed were promised that officers would no longer be permitted to beat them, and that soldiers’ committees would be formed in each unit to ventilate grievances and ensure that democratic practices were followed. Secondly, Mao said, the soldiers would be required to treat civilians correctly. They must speak politely; pay a fair price for what they bought; and never take so much as ‘a solitary sweet potato’ belonging to the masses.58

In a country which lived by the aphorism ‘Do not waste good iron making nails, nor good men as soldiers’, where a ‘good’ army merely took what it wanted and a ‘bad’ army marauded, looted, burned, raped and killed, and where officers routinely employed barbaric methods of discipline, this was a genuinely revolutionary concept.

The question remained, however, where Mao's forces should go next.

The area in which they found themselves, on the border between Hunan and Jiangxi, was riven by conflict between the descendants of early Han settlers, who had arrived in the lowland valleys during the Tang and Song dynasties, and Hakka – ‘guest people’ – from Fujian and Guangdong, who had occupied the highlands several centuries later.59 On that basic fault-line were superimposed a culture of banditry, the depredations of government troops and militias, struggles for influence among local satraps and their sworn followers, and, in the early 1920s, the arrival of large numbers of deserters from warlord forces in the region. Every landlord and family of substance had armed retainers to defend its property. In 1926, local communists had begun setting up peasant associations and succeeded in co-opting two prominent bandit leaders, Yuan Wencai and Wang Zuo, whose men – members of a gang known as the Horse-knife (or Sabre) Detachment – were then reorganised into peasant self-defence units. By the time Mao arrived, however, the collapse of the united front had triggered a White Terror which had left both the peasant associations and local Party organisations in disarray.

In these unpropitious circumstances, Mao sent a messenger from Sanwan with a letter to Yuan Wencai, whose forces were at Ninggang, fifteen miles to the south.60 By a stroke of luck one of Yuan's aides had met Mao at the GMD Peasant Training Institute in Wuhan. Through his good offices, aided by a gift of rifles from Mao to Yuan's emissaries, it was agreed that the communist army could proceed to the small town of Gucheng in Ninggang, where a two-day meeting was held with local Party officials and Yuan's representatives. Both sides were at first extremely wary. Mao's colleagues – though not, apparently, Mao himself – were reluctant to ally themselves with bandits; the local Jiangxi communists worried that the arrival of Mao's troops would erode their own power; and Yuan and his followers feared, not unreasonably, that in the end they risked losing their independence and being assimilated into Mao's larger and better-armed force. None the less, on October 6, the two leaders met face to face and worked out a modus vivendi. Mao offered Yuan's men a hundred rifles; Yuan furnished provisions and money; and the newcomers were allowed to establish a hospital to treat their wounded and a headquarters base at Maoping, a small market town in a river valley, encircled by low hills, from which the main western route into Jinggangshan, a narrow, sandy track, no wider than a footpath, wound its way up through the forest to the heights, 1,500 feet above.

For the next ten days, Mao hesitated. The alternative was to go further south, to the Hunan–Guangdong border, and to try to link up with Zhu De and He Long, who should have arrived there from Nanchang. But an initial probe into southern Hunan ended with Mao's troops being mauled near the village of Dafen. Then, in mid-October, he learned from a newspaper that He's forces had been defeated and scattered. He no longer had any choice.

Militarily, Jinggangshan, if properly defended, was all but impregnable. It lies at the junction of four counties – Ninggang, Yongxin, Suichuan and Lingxian – in the heart of the Luoxiao range, which follows the Hunan–Jiangxi border southward as far as Guangdong. The massif itself consists of a swathe of louring black mountains, wreathed in cloud, with blade-sharp ridges, thickly forested with Chinese larch, pine and bamboo, where waterfalls cascade down sheer gorges to lose themselves in thin, blue torrents, far below, and tall pinnacles of bare rock jut from unseen cliffs behind an impenetrable weft of subtropical vegetation. It is a poet's landscape, majestic but desperately poor.

On the heights there was barely enough farmland, carved from the hillsides and small areas of plateau, to support the population of just under 2,000, who lived in ramshackle wooden houses and small, almost windowless stone huts, scattered between the main settlement, Ciping, where half-a-dozen merchants had built shops and a weekly market was held, and the five villages – Big Well, Little Well, Middle Well, Lower Well and Upper Well – from which Jinggangshan (Well Ridge Mountain) took its name.61 The villagers ate a local variety of red-coloured wild rice, and trapped squirrels and badgers for food. Grain for the troops had to be brought up the mountain on men's backs from the more fertile counties in the plains.

Maoping became Mao's main forward base. For the next twelve months, whenever the military situation stabilised, the army made its headquarters there. He set the troops three main tasks. In battle, Mao said, they must fight to win. In victory, they must expropriate the landlords, both to provide land for the peasantry and to collect funds for the army's own needs. And in peacetime they must strive to win over ‘the masses’, the peasants, workers and petty bourgeoisie. In November, the army occupied Chaling, thirty miles to the west, and proclaimed the setting-up of a ‘Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Soviet Government’, the first in the border area. It was overthrown a month later, when government forces returned, but other border soviets soon followed, in Suichuan in January 1928, and in Ninggang in February. Even though such successes were ephemeral, they procured badly needed supplies and symbolically they showed the local population that the existing power structure was fragile and could be changed.V

When the pressure from government troops became too great, Maoping was abandoned and they withdrew up the mountain to Wang Zuo's stronghold at Dajing (Big Well), about twelve miles to the south, from which they could control the passes. Wang lived in a former landlord's house which his men had commandeered, a palatial residence for that poor place, with whitewashed walls and gables, delicately upturned eaves beneath roofs of slate-coloured tile, ornamented ridgework, and more than a dozen wood-panelled rooms, furnished with tables and four-poster beds, built around three large inner courtyards, each open to the sky with a sunken well in the middle to drain away rainwater. Mao had approached Wang Zuo, as he had Yuan Wencai, with a large gift of rifles and the offer of communist instructors to give his force military training. Wang was initially wary, but after the training group's leader, He Changgong, helped him defeat a landlord militia unit which had been harassing his men, he, too, was won over.

That winter gave Mao a breathing space to start learning his new military trade. He had grasped the importance of leading by example, compelling exhausted men to follow him by sheer force of will. Since most of the soldiers were illiterate, he started using folk-tales and graphic images to get his points across. ‘The God of Thunder strikes the beancurd’, he told them, explaining why they should concentrate their forces to attack the enemy's weak points. Chiang Kai-shek was like a huge water-pot, while the revolutionary army was just a small pebble. But the pebble was hard, and by dint of constant tapping, one day the pot would break.

The lull could not continue indefinitely. In mid-February, Yuan Wencai's and Wang Zuo's forces were combined to form the army's 2nd Regiment, with He Changgong as Party representative and a leaven of communist cadres down to company level. Ten days later, news came that the Jiangxi Army had despatched a battalion to occupy Xincheng, about eight miles north of Maoping. During the night of February 17, Mao led three battalions of his own men to surround them. At dawn, as the enemy troops were at their morning exercises, he gave the order to attack.

The fighting lasted several hours. When it was over, the enemy commander and his deputy were both dead and more than a hundred prisoners had been taken. After they had been escorted back to Maoping, Mao told them, to their amazement – as he had his own men at Sanwan, five months earlier – that anyone who wished to leave would be given money and allowed to depart. Those who decided to stay would be enrolled in the revolutionary army. Many did stay. The technique proved so effective that later some nationalist commanders began setting free communist prisoners in an attempt to emulate it.62

Mao's victory had its price. As the Hunan and Jiangxi commanders realised the nature of the enemy they were dealing with, they began assembling stronger forces to attack the Jinggangshan redoubt, and imposed an economic blockade. But his concerns on that score were soon to be overshadowed by problems of a very different kind.

Since October 1927, Mao had been trying to get in touch with the Hunan provincial committee, the hierarchical superior of the Front Committee he now headed. Some of his messages evidently got through, for in mid-December the Party Centre was sufficiently informed of his activities to write to Zhu De, who was then in northern Guangdong, suggesting that he link up with Mao. Unknown to the leaders in Shanghai, Zhu had already made contact with the Jinggangshan base some weeks earlier, sending as a messenger none other than Mao's youngest brother, Zetan, who had accompanied Zhu's forces from Nanchang. From then on the two armies were in sporadic communication. But the Politburo was divided in its appraisal of Mao's conduct. Qu Qiubai, who recognised and admired Mao's independent spirit, was ready, within limits, to let him act as he saw fit.63 Zhou Enlai, who remained in charge of military affairs and had become one of Qu's most powerful colleagues, strongly disapproved of Mao's tactics. His troops had ‘a bandit character’, Zhou argued, and were ‘continually flying from place to place’.64 In a CC circular on armed insurrection issued in January 1928, he cited Mao's leadership of the Autumn Harvest Uprising in Hunan as an example of how not to behave:

[Such leaders] do not trust in the strength of the masses but lean towards military opportunism, they draft their plans in terms of military forces, planning how to move this or that army unit, this or that peasant army, this or that workers’ and peasants’ armed suppression group, how to link up with the forces of this or that bandit chieftain … and in this way how to unleash an ‘armed uprising’ by a plot masquerading as a plan. Such a so-called armed uprising has no relation whatever to the masses.65

Zhou was almost certainly responsible for another CC directive, which also reached Changsha in January 1928, accusing Mao of ‘serious political errors’ and authorising the Hunan provincial committee to remove him as Party leader in the border area and to draw up a new work plan for the army which would ‘accord with practical needs’.66

The bearer of these tidings, Zhou Lu, a junior member of the South Hunan Special Committee,VI arrived at Maoping in the first week of March. He went to work with a vengeance, not only telling Mao that he had been dismissed from the Politburo and the Hunan provincial committee – which despite his rows with the Party Centre six months earlier must have come as a bolt from the blue – but also informing him, falsely, that he had been expelled from the Party. Whether this was a simple mistake, or a deliberate manoeuvre to destroy Mao's authority, is unclear. But, coming as it did, after months of hardship, just as the army had won its first victory and the base area was at last beginning to take shape, it must have been a crushing blow. The injustice of the rebuke, Mao wrote later, had been intolerable.67

In his new, ‘non-Party’ role, Mao became divisional commander (a post which had been left vacant when the 2nd Regiment was formed in February). The Front Committee was abolished, and Zhou Lu acted as Party representative.68

At this point, local rivalries intervened. The prime concern of the provincial Party committee was to promote the revolution in its own area. The previous December, Zhu De's force had left its base in Guangdong and marched north into south-eastern Hunan, where it sponsored peasant uprisings in the border town of Yizhang, and at Chenxian and Leiyang, further north, and set up ‘Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Soviets’.69 But the economy of the area was in ruins and Zhu's troops had to resort to selling opium in order to feed themselves. Zhou Lu's first action on taking charge at the beginning of March was to order Mao's division to Hunan to link up with Zhu so as to strengthen the forces under the Hunan Party committee's control. Mao complied, but hurried slowly. Two weeks later his forces were still only a few miles from the Jiangxi border. But when Zhu's troops were attacked by regular Hunan and Guangdong government forces, Mao's 2nd Regiment had to rush to their aid. By the time they had extricated themselves, Zhou Lu had suffered the ultimate penalty for the Hunan committee's mischief-making: he had been captured and executed. Mao marched north to Linxian, where the pursuing forces were repulsed. The base area, which had been overrun by landlord militia, was reconquered, and either in Linxian or Ninggang – recollections differ – he and Zhu met for the first time towards the end of April 1928.

Zhu was forty-one, seven years Mao's senior. Agnes Smedley, who spent several months with him in the 1930s, wrote that where Mao, with his ‘strange, brooding mind, perpetually wrestling with the … problems of the Chinese revolution’, was essentially an intellectual, Zhu was ‘more a man of action and a military organiser’:

In height he was perhaps five feet eight inches. He was neither ugly nor handsome, and there was nothing whatever heroic or fire-eating about him. His head was round and was covered with a short stubble of black hair touched with grey, his forehead was broad and rather high, his cheekbones prominent. A strong stubborn jaw and chin supported a wide mouth and a perfect set of white teeth which gleamed when he smiled his welcome … He was such a commonplace man in appearance that had it not been for his uniform [which was worn and faded from much wear and long washing], he could have passed for almost any peasant in any village in China.70

Yet Zhu's life encapsulated, even more than Mao's, the welter of contradiction and change that had swept across China at the end of the old century and the beginning of the new. Born into a Sichuanese peasant family so poor that his father had drowned five of his children with his own hands because he was unable to feed them, he had advanced to win a degree as a xiucai, the first step towards becoming a mandarin. Instead, he became a petty warlord and an opium addict. In 1922, after a cure in Shanghai, he took ship to Europe. There he met Zhou Enlai, who inducted him into the Communist Party. For four years he studied in Berlin, before returning to China to resume his military career – this time on the communists’ behalf – in the Guomindang's crack Fourth Army, the proudly named ‘Ironsides’.71

The partnership between Mao and Zhu De marked the heyday of the Jinggangshan base area, which rapidly expanded to include, at its peak that summer, parts of seven counties with a population of more than 500,000.

Mao's political fortunes also improved. He learned from Zhu in April that his expulsion from the Party had never happened. Then, in May, word came from the provincial Party leadership that the establishment of a Hunan–Jiangxi Border Area Special Committee, which Mao had been urging since December, had at last been authorised, and that he should be its secretary.72

The two armies merged to form the Fourth Workers’ and Peasants’ Revolutionary Army (so numbered after the GMD Fourth Army, from which Zhu and most of his officers had come), soon afterwards rechristened – with the Politburo's blessing – the Fourth ‘Red Army’, a name-change of no small importance for it signalled the beginning of the end of the long and sterile debate over the respective roles of the army and the insurrectionary masses. A ‘Red Army’ was by definition insurrectionary, so no such distinction could arise.

The Zhu–Mao Army, as it became known, comprised four regiments, totalling about 8,000 men: the 28th, which had, as its core, the ‘Ironsides’ troops Zhu had brought from Nanchang; the 29th, composed mainly of Hunanese who had taken part in the uprising at Yizhang; the 31st, which was Mao's old 1st Regiment; and the 32nd (the former 2nd Regiment) under Yuan Wencai and Wang Zuo. Although they had only 2,000 rifles, it was far and away the biggest communist force in the country. In the interest of unity, the divisional commands were abolished. Zhu became Army Commander; Mao, Party representative; and Chen Yi, formerly Zhu's deputy, Secretary of the Party's Military Committee.73

On May 20, sixty delegates from the Red Army and from six county Party committees gathered in the Clan Hall of a wealthy landlord family in Maoping for the First Congress of Party Organisations of the Hunan–Jiangxi Border Area. After three days of debate, the Congress confirmed Mao's appointment as head of the Border Area Special Committee and elected him Chairman of the Border Area ‘Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Government’ with Yuan Wencai as his deputy.74

Despite the junction with Zhu De, it was a time of considerable pessimism. The defeat of Zhu's forces in Hunan, and the ease with which landlord forces had regained control of the base area as soon as the Red Army left, had raised doubts in many minds about the validity of the insurrectionary strategy. In his speech, therefore, Mao posed the question: ‘How much longer can the Red flag be upheld?’ It was a theme to which he would return repeatedly as the year wore on:

The prolonged existence inside a country of one or more small areas under Red political power, surrounded on all sides by White political power, is something which has never occurred anywhere else in the world. There are special reasons for the emergence of this curious thing … It occurs solely in [semi-colonial] China, which is under indirect imperialist rule … [and where there are] prolonged splits and wars among the White political forces … [Our] independent regime on the borders of Hunan and Jiangxi is one of many such small areas. In difficult and critical times, some comrades often have doubts as to the survival of such Red political power and manifest negative tendencies … [But] if only we know that splits and wars among the White forces will continue without interruption, we will have no doubts about the emergence, survival and daily growth of Red political power.75

A number of other conditions were also necessary, he maintained. Red areas could exist only in provinces like Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi and Guangdong, where strong mass movements had developed during the Northern Expedition, and only if ‘the revolutionary situation in the nation as a whole continues to move forward’ (as Mao insisted was the case in China). They required regular Red Army forces to defend them, and a strong Communist Party to lead them. Even then, he acknowledged, there would be times when it was difficult to hold out: ‘Fighting among the warlords does not go on every day without ceasing. Whenever the White political power in one or more provinces enjoys temporary stability, the ruling class … will surely exert every effort to destroy Red political power.’ But, Mao declared, among the White forces, ‘all compromises can only be temporary; a temporary compromise today prepares the ground for a bigger war tomorrow.’

The correct course at this stage, therefore, Mao argued, was not to career about the country, setting off uprisings which collapsed as soon as the army left, but to concentrate on deepening the revolution in a single area.

When the Congress ended, Mao's policy was approved.

At a time when Jinggangshan was under constant enemy pressure – in the three weeks since Zhu De's arrival, two more sizeable enemy offensives had been thwarted – such a strategy required solid nerves. But Mao was growing more confident in his new role as a military tactician. During the winter Wang Zuo had told him stories about Zhu the Deaf, an old bandit leader whose maxim was: ‘You don't need to fight, all you need to do is circle around’.76 The moral, Mao told his troops, was to stay clear of the enemy's main forces; lead them in circles; and when they were confused and disoriented, strike where they were weakest.

This was summed up in a pithy folk-rhyme, which conveyed the essence of the Red Army's future strategy. In its final form, drawn up by Mao and Zhu, and popularised throughout the army in May, it contained sixteen characters:

| Di jin, wo tui, | [When the] enemy advances, we withdraw, |

| Di zhu, wo rao, | [When the] enemy rests, we harass, |

| Di pi, wo da, | [When the] enemy tires, we attack, |

| Di tui, wo zhui. | [When the] enemy withdraws, we pursue.77 |

In the months following, two further principles were laid down:

Concentrate the Red Army to fight the enemy … and oppose the division of forces so as to avoid being destroyed one by one.

In expanding the area under [our control], adopt the policy of advancing in a series of waves and oppose the policy of rash advance.78

The Zhu–Mao Army was still of very uneven quality.[Q3] Zhu's 28th regiment and Mao's 31st were a match for the best warlord units. The tactics they developed, employing speed and mobility to make feints to deceive the enemy, followed by surprise attacks from the rear or on the flanks, won them such a fearsome reputation that their adversaries would often withdraw without giving battle. Notwithstanding Mao's attempts to tighten discipline, gambling, opium use, desertion and pillaging remained widespread problems. But the men had an esprit de corps and cohesiveness which their opponents lacked. The 32nd regiment, based on Yuan Wencai's and Wang Zuo's bandit troops, was less effective but still able to play a defensive role. Only the 29th, composed of homesick Hunanese peasants, was unreformable.79

Meanwhile the guidelines for the army's treatment of civilians, which Mao had first issued after the halt at Sanwan in September 1927, were expanded into what became known as the ‘Six Main Points for Attention’. Soldiers were urged to replace straw bedding and wooden bed-boards after staying at peasant homes overnight; to return whatever they borrowed; to pay for anything they damaged; to be courteous; to be fair in business dealings; and to treat prisoners humanely. Later, two further ‘Points for Attention’ were added by Lin Biao: ‘Don't molest women’ (in early versions, ‘Don't bathe in sight of women’); and, ‘Dig latrines well away from homes and cover them before leaving.’ At the same time, ‘Three Main Rules of Discipline’ were issued: ‘Obey orders’; ‘Don't take anything belonging to the masses’ (the original phrase, ‘not so much as a sweet potato’, was amended to ‘not even a needle or thread’); and, ‘Turn in for public distribution all goods confiscated from landlords and local bullies.’80

The thrust of Mao's revolutionary strategy was thus fundamentally different from the insurrectionary approach of Qu Qiubai. Where Qu believed the old system could be overthrown by the raw fervour of untrained peasants and workers, rising to seize power with their own hands, Mao saw the peasantry as a reservoir of sympathy and support – a ‘sea’, as he would later describe it, in which the ‘fish’ (the Red guerrillas) could swim. Even on Jinggangshan, he noted soberly, few local people volunteered for the Red Army. As soon as the landlords had been toppled and their fields had been divided up, all the peasants wanted was to be left in peace to farm. For the same reason he urged moderation towards the urban petty bourgeoisie, the stall-holders and traders in the small market towns, in order to avoid driving them to oppose the revolution. Excesses were often unavoidable, he acknowledged, and could be a useful means of radicalising public opinion. But, in practice, they were frequently counter-productive: ‘In order to kill people and burn houses, there must be a mass basis … [not just] burning and killing by the army on its own.’ Revolutionary violence was helpful, he argued, only when it had a clear purpose and was backed by a movement strong enough to resist the retribution which would inevitably follow.81

When Zhou Lu had arrived in March, Mao had been severely criticised for these views. His work was ‘too right-wing’, he had been told. He was ‘not killing and burning enough, [and] not carrying out the policy of “turning the petty bourgeois into proletarians and then forcing them to make revolution”.’82 But by then, unknown to Zhou (let alone to Mao), the Politburo in Shanghai was also having second thoughts:

The peasant movement throughout the country [Qu Qiubai wrote in April] seems to feel that, besides killing the gentry, it ‘must’ set houses on fire … Many villages in Hubei have been reduced to ashes. The leader of a certain locality in Hunan proposed burning down an entire county town, taking with him only the things the peasant insurgents needed (stencil machines and so forth), and to kill everyone unless they joined the revolution … This [is a] petty bourgeois tendency … The proletariat was not leading the peasants, but the peasants were leading the proletariat.83

The moderate policies Mao put forward at the First Border Area Party Congress in May came, therefore, at an opportune time. Less than a week later, the new Hunan provincial committee,VII apparently chastened by the fiasco of Zhu De's expedition that spring, agreed that the Zhu–Mao Army should remain based at Jinggangshan, and warned indignantly of the foolishness of ‘burning whole cities’, which allowed Mao to reply, tongue firmly in cheek: ‘The provincial committee points out that it is wrong to burn cities. We shall never commit this mistake again.’84

Soon afterwards the Central Committee approved Mao's strategy too. At the beginning of June, a letter from the base area finally reached Shanghai – the first direct communication since its creation the previous October.85 Most of the leadership was away in Moscow, preparing for the Sixth Party Congress, which the Comintern had decided should be held not in China, where Chiang Kai-shek's ‘White terror’ was in full flood, but in the Soviet Union (where the Russians could also exert tighter control).86 It fell to Li Weihan, Mao's friend from New People's Study Society days, who had been left in charge, to draft the Central Committee's reply. He enthusiastically supported Mao's leadership; proposed that the Front Committee, which Zhou Lu had abolished, be restored; and endorsed Mao's decision to focus on building up the Jinggangshan base as a centre from which to propagate the revolution in both Hunan and Jiangxi – decisions in keeping with the new spirit of realism which would mark the Congress proceedings.87

Two weeks later, the 118 delegates who gathered in a dilapidated old country house near Zvenigorod, forty miles north-west of Moscow, frankly acknowledged that there was no ‘revolutionary high tide’ in China, and no sign that one was imminent.

The Party, they declared, had overestimated the strength of the peasants and workers, and underestimated the forces of reaction. China was still engaged in a bourgeois-democratic revolution, and the main tasks were to unify the country against the imperialists; to abolish the landlord system; and to set up soviets of workers, peasants and soldiers, in order ‘to induce the vast, toiling masses to participate in political rule’. Socialist revolution could come later.88

These themes had already been sounded (and in Shanghai had been largely ignored) in a Comintern resolution the previous February, which had also stressed the importance of co-ordinating rural revolution with uprisings in the cities.89 But Bukharin, who was overseeing the proceedings on Stalin's behalf, now introduced an important qualification. ‘[We may] maintain [the slogan of] carrying out uprisings,’ he said. ‘[But] this does not mean that in a country as large as China … the innumerable masses will suddenly rise up in an extremely short period of time … That cannot happen.’ The Chinese leaders needed to steel themselves for an uneven, protracted struggle, in which victories in some areas would be offset by defeats in others. Even then, a long period of preparation was essential before province-wide uprisings could occur.90

Accordingly, the Congress approved a strategy of guerrilla warfare to weaken the Guomindang's hold on the rural areas, and establish local soviets, even if initially only ‘in one county or several townships’. Military power, it declared, was ‘highly significant’ in the Chinese revolution, and the development of the Red Army must be the ‘central issue’ in the countryside.91 By contrast, the doomed heroics of small groups of fanatics, acting with no mass base, were sharply condemned, especially in urban areas. In Bukharin's words:

If uprisings directed by the Party fail once, twice, three times, four times, or are crushed 10 or 15 times, then the working class will say: ‘Hey, you! Listen! You are probably excellent people; nevertheless, please get out of here! You do not deserve to be our leaders.’ … This [kind of] excessive showing off is of no use to a Party, however revolutionary.92

Urban uprisings were not explicitly ruled out. But the whole thrust of Bukharin's speech, and of the Congress resolutions, was that, at this stage at least, the peasantry, not the workers, were the main revolutionary force – the only proviso being that the peasants should be under proletarian leadership to restrain their anarchistic, petty-bourgeois leanings.93

These decisions, Mao wrote later, provided ‘a correct theoretical basis’ for the base areas and the Red Army to develop.94

Neither the Central Committee's letter of early June, nor the Congress resolutions, reached Jinggangshan until several months later. But there were enough straws in the wind to indicate that the Party line had changed. Mao's life changed, too, that summer, but in a different way: he acquired ‘a revolutionary companion’.95

She was eighteen years old, and her name was He Zizhen. A lively, independent-minded young woman, with a slender, boyish figure, the fine features and winning smile of her Cantonese mother, and the literary bent of her father, a local scholar, she had joined the Party at the age of sixteen, becoming the first and for some time the only female Party member in that area while still a student at the local mission school, run by Finnish nuns. As Mao would later find to his cost, she was tough and strong-willed. Zizhen had been the first young woman in the county to cut her hair short, in what was then regarded as a scandalous affront to traditional values; she had mobilised fellow students to burn the statue of the City God in the local temple; and in the summer of 1926, she had fought alongside Yuan's men in a battle against a landlord militia, earning herself the nickname, ‘The Two-Gun Girl General’.

Yuan, who had been a classmate of her elder brother, had introduced her to Mao soon after his arrival, and the following spring she began working as his assistant. She wrote later that when she realised she was falling in love with him, she had tried to hide her feelings. But, one day, Mao caught her gazing at him longingly and realised what had happened. He pulled up a chair, asked her to sit down, and then talked to her of Yang Kaihui and the children whom he had left behind in Changsha. Shortly after that conversation, they started living together.96 Mao had long since declared his disdain for marriage conventions, and on the Jinggangshan there seemed even less reason to heed them. Wang Zuo had three wives. Zhu De, who had left his own wife and small son in Sichuan, six years earlier, also began living with a much younger woman.97

None the less, Mao evidently felt a twinge of guilt at his disloyalty to Yang Kaihui. To justify himself, he told He Zizhen that he had had no news from her and thought she might have been executed. In fact he had made no attempt since the uprising to contact his family in Changsha.98 His decision to take the young woman as his partner seems to have been an almost conscious step in a gradual cutting of the ties that bound him to the world outside, the ‘normal’ world that had been his before the revolution claimed him.

When word reached Kaihui in the winter of 1928 that Mao had acquired a new ‘wife’, she became deeply depressed.VIII In the first years of her marriage, she had been consumed by jealousy of his old flame, Tao Yi, with whom she suspected (apparently wrongly) that he was carrying on an affair. Now, she wrote bitterly, he had abandoned her completely. She had contemplated suicide, she added, but had held back for the sake of their children.

The political respite was soon over. Once more, the cause lay in provincial rivalries. The Jiangxi Party committee had been badgering Mao to attack the city of Jian, seventy miles to the north-east. Now a succession of envoys arrived from Hunan, demanding, each more insistently than the last, that the Fourth Red Army send its main forces to the districts south of Hengyang, for a further attempt at insurrection in the same area where Zhu De had been defeated in March.99

This was not as illogical as it might sound. Hengyang controlled the main corridor from central to southern Hunan. A successful uprising in the area would make it possible to link Hunan and Guangdong – traditionally the two ‘most revolutionary’ provinces – by establishing a new base area in the region where Tan Yankai had stationed his southern armies, a decade earlier, while waiting his chance to attack Changsha. But precisely for that reason, as Mao and Zhu well knew, it was far too well-defended for the Fourth Army to attack.

The Hunan Provincial committee plainly expected Mao to resist, for it informed him that a special emissary, 23-year-old Yang Kaiming,IX was on his way to Jinggangshan to take personal charge of the Border Area Special Committee, adding peremptorily: ‘You must carry out [our instructions] immediately without any hesitation.’ Shortly before he arrived, however, a joint meeting of the Special Committee and the fourth Army's Military Committee, held under Mao's chairmanship on June 30, in the presence of another, even younger, provincial committee representative, twenty-year-old Du Xiujing, voted against the plan to strike into Hunan. In a message to the provincial leadership in Anyuan, Mao warned that, if they went ahead, the entire Fourth Army might be lost.100 Yang evidently did not feel himself strong enough to countermand this decision and for the next two weeks there was an uneasy stand-off.

Word then came that elements of the Hunan and Jiangxi armies were preparing another attack on Jinggangshan. It was decided that Zhu's 28th and 29th regiments should cross into Hunan, to attack the Hunan army's rear. Mao's troops, the 31st and 32nd, would block the Jiangxi units’ advance until Zhu's men could return.

The first part of the battle plan went well enough. But as Zhu was about to march back to link up with Mao's troops, as arranged, Du Xiujing, who was accompanying Zhu's forces, invoked superior Party authority to insist that the provincial committee's original orders must now be carried out. After some discussion, Zhu's two regiments set off for Chenzhou, ninety miles south of Hengyang. The result was exactly as Mao had foreseen. After initial successes, they were routed by Hunan government troops and retreated in disarray into the hills. With the Red Army's main force absent, Ninggang and two neighbouring counties in the plain were overrun. Yet another letter from the provincial committee then arrived urging Mao to take his remaining forces to support Zhu in southern Hunan. But even as the Border Area Special Committee was discussing this latest instruction, a messenger burst into the meeting room with the news that Zhu had suffered a crushing defeat. The 29th regiment had disintegrated: its Hunanese peasant troops had deserted and fled to their home villages in the region. The 28th was limping back to Jinggangshan.101

The Fourth Army's troubles were not yet over. When Mao set out to join Zhu at Guidong, south-west of Jinggangshan, government troops took advantage of their disarray to launch another attack. This time they came perilously close to occupying the fastness itself.

On August 30, a young communist officer named He Tingying led a single under-strength battalion to hold the narrow pass of Huangyangjie, commanding the heights above Ninggang, against three regiments of the Hunanese Eighth Army and one regiment of Jiangxi troops. The Hunanese units suffered heavy casualties, and by nightfall, when the attack was abandoned, their morale had been broken.102 Mao was moved to take up his writing brush to commemorate the event:

Our defence is like a stern fortress,

Our wills, united, form a yet stronger wall.

The roar of gunfire rises from Huangyangjie,

Announcing the enemy has fled in the night.103

Mao's position was ambiguous. Yang Kaiming had taken over in mid-July as acting Secretary of the Border Area Special Committee. But at Guidong, Mao had engineered the creation of a rival ‘Action Committee’, representing the army, with himself as Secretary.104

Meanwhile, the south Hunan expedition had revived tensions between himself and Zhu De that had been papered over when their forces had come together in April. Zhu had evidently relished the opportunity to break free from Mao's tutelage and resume his old role as sole military commander. Having tasted freedom anew – even though it had ended in defeat – he was now reluctant to allow Mao to regain the dominant position he had occupied during the summer.105 Moreover, some of Zhu's followers, and perhaps Zhu himself, privately attributed the debacle to Mao's refusal to let the 31st and 32nd regiments go with them, as the Hunan Committee had originally proposed.106

The formal division of powers between Mao and Yang Kaiming was confirmed at the Second Border Area Party Congress at Maoping in October. Yang remained head of the Border Area Special Committee – although soon afterwards he fell ill and a neutral figure, Tan Zhenlin, a former worker in his mid-twenties who had been head of the first soviet government Mao had set up at Chaling, was appointed in his place. Mao retained his ‘Action Committee’ post – which effectively made him the Army's Political Commissar. But, in the Committee ranking, which was based on a free vote of delegates, he finished near the bottom of the list. The explanation was provided by the Congress's political resolution. ‘In the past’, it stated, ‘the Party organs were all individual dictatorships, autocracies of the Party secretary; there was no collective leadership or democratic spirit whatsoever.’ Comrade Mao, it noted drily, was among the main offenders.107

His policies were still respected: the political strategy the Congress approved, based on the Comintern resolution of the previous February, details of which had reached the mountains that autumn, closely reflected Mao's ideas. But, his colleagues told him, his leadership style left much to be desired.108

This anomalous situation was brought to an end at the beginning of November, when, after a journey lasting nearly five months, the Central Committee directive which Li Weihan had drafted in June arrived on Jinggangshan.109