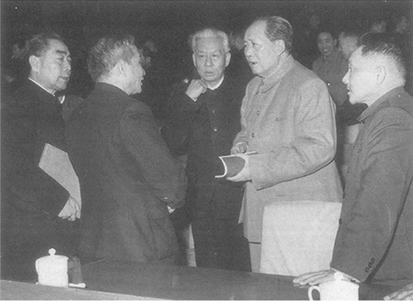

Plate 33 Members of the Politburo Standing Committee in a rare, unposed shot at the ‘7,000-cadre big conference’ in January 1962. From left: Zhou Enlai, Chen Yun, Liu Shaoqi, Mao and Deng Xiaoping.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Things Fall Apart

Six weeks after Liu Shaoqi's death, Mao celebrated his seventy-sixth birthday. He was a heavy smoker and suffered from respiratory problems. But, that apart, his health was good. His doctor, returning after a year's absence, found that he was still waited on by a harem of young women, and would sometimes invite ‘three, four, even five of them simultaneously’ to share his great bed.1

With age, he had grown increasingly capricious and unpredictable. He had always expected his subordinates to stay in tune with his thinking – if not to anticipate him, at least not to get out of line. All the major victims of the previous two decades, Gao Gang, Peng Dehuai, Liu, Deng and Tao Zhu, had fallen because they failed that test. But now it was growing even harder to fathom the Chairman's true intentions. Not only would he push a policy to its extreme and then abruptly reverse it – as he had with the Shanghai Commune, and with the purge of ‘capitalist-roaders’ in the army in 1967 – which invariably left his supporters wrong-footed; but, more often than in the past, he would deliberately conceal his real views, or cloak them in utterances of Delphic ambiguity, in order to see how others would react.

A whiff of paranoia began to emanate from the Study of Chrysanthemum Fragrance. ‘In his later years’, one Politburo radical wrote, ‘almost nobody trusted him. We very seldom saw him, and … when we [did], we were terrified of saying something wrong in case he took it as an error.’2

The result was that all Mao's colleagues assumed the role, and the habits, of courtiers.

Zhou Enlai was best at it. It was he who, in March 1969, realising that the Chairman's ruling to exclude Jiang Qing from the new Politburo was merely to avoid the appearance of nepotism, put her name (and that of Ye Qun) on the list anyway. It was Zhou, too, who, in his speech to the Ninth Congress, spoke of Mao having developed Marxism-Leninism ‘creatively’ and ‘with genius’, terms which the Chairman had deleted from the new Party constitution. Again, he judged correctly. What Mao found unacceptable in the CCP's public statutes was one thing; what might please him in a speech confined to the Party faithful was quite another.3

But good judgement alone was not enough. Mao's suspiciousness required that he be constantly reassured of the loyalty of his inner circle.

Zhou survived because he would betray anyone he thought necessary to maintain the Chairman's trust. When his adopted daughter was tortured by Red Guards and then thrown into prison, where she eventually died from maltreatment, Zhou was informed – but refused to take any action to protect her. To do otherwise, he reasoned, would expose him to charges of putting family before politics. The most vicious attack on Deng Xiaoping by any leader during the Cultural Revolution was contained in a minute appended to a ‘Special Case Group’ report, not by Jiang Qing or Kang Sheng – but by Zhou.4 In statements to the Cultural Revolution Small Group, he denounced exceptionally harshly the failings of the veteran cadres.5 Even his chief bodyguard, a close companion of many years’ standing, was abandoned the moment Jiang Qing, on a whim, took against him; Zhou's wife, Deng Yingchao, urged that the man be arrested because ‘we don't want to show any favouritism towards him’.6

The Cultural Revolution Small Group, in the late 1960s, was even more a nest of vipers than the Politburo a decade before.

This was partly due to the amoral nature of the movement itself, which sapped whatever vestiges of probity might have remained. But the presence of Jiang Qing certainly did not help. In middle age, she had become shallow, vindictive and totally self-centred. Many of those who had been kind to her early in her career were now hunted down and imprisoned to ensure that they could not divulge details of her actress past.7 When she learned that Chen Boda had contemplated suicide after Mao had criticised him, she laughed in his face, telling him, ‘Go ahead! Go ahead! Do you have the courage to kill yourself?’8 Kang Sheng, whose own career had profited from his early support of her liaison with Mao, viewed her as dangerous and unreliable. Lin Biao could not abide her, and became so enraged during one meeting at Maojiawan that he told Ye Qun (out of Jiang's hearing, however): ‘Get that woman out of here!’9 Even Mao lost patience with her. But, like Zhou, she was useful to him. And, because she was a conduit to Mao, she was useful to others. The Shanghai radicals clung to her with limpet-like devotion, acting as front men in her unremitting efforts to undermine Zhou Enlai. So, to a lesser extent, did Kang Sheng and Xie Fuzhi, although in Kang's case that would change.

Before 1969, these personal animosities were subsumed into the larger struggle to eliminate ‘capitalist-roaders’ and promote the radical cause.

At the Ninth Congress they began to spill over into policy. In his report, Lin had wanted to put the emphasis on promoting production and raising living standards. Mao had insisted that the main message be the need to continue the Cultural Revolution. He had rejected Chen Boda's draft, which had been based on Lin's ideas, and instructed Zhang Chunqiao to draw up an alternative. When Lin received it, he put it to one side and reportedly refused to sign the text. Zhang's allies would later accuse him of deliberately reading it out at the Congress in a perfunctory fashion to indicate that he disapproved of its contents.10

Within the Politburo, Jiang Qing and Lin Biao had roughly equal support. In theory, Lin was stronger. He controlled the army, which in turn controlled China. However, Jiang Qing had a privileged relationship with Mao, who controlled everything. In Lin's eyes, that was an uncertain advantage. The Chairman did not always take his wife's side.

Since they had few overt policy differences – whatever Lin may really have felt about the Cultural Revolution, he was too canny to let it show – the only ground for their rivalry was power. They fought their battles by palace conspiracies, whose sole and unique purpose was to win the Chairman's favour. Thus was the basis established for a succession of events which, over the next two years, would blow apart all Mao's carefully laid plans to ensure that his policies survived him.

It began simply enough. Liu Shaoqi's disgrace and death had created a vacancy for the post of Head of State. In March 1970, as part of the general rebuilding of the Chinese polity after the Cultural Revolution, Mao set out guidelines for a revised state constitution, under which that office would be abolished and the ceremonial functions attached to it would devolve to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, the Chinese parliament. This was approved by the Politburo and, soon afterwards, by a Central Committee work conference.

Lin rarely attended Politburo meetings, and was therefore absent when these decisions were taken. Five weeks later, however, on April 11, he sent a message to Mao, urging him to reconsider and take back the post himself on the grounds that otherwise ‘it would not be in accordance with the psychology of the people’ – in other words, as the incarnation of the Chinese revolution, the Chairman should be surrounded by the full panoply of state honours. Next day, Mao turned him down. ‘I cannot do this job again,’ he told the Politburo. ‘The suggestion is inappropriate.’ Later that month he reiterated that the post did not interest him.11

None the less, Mao was intrigued.12

That Lin should have made such a suggestion was wholly out of character. Where Zhou Enlai made a religion of loyalty, Lin's fetish was passivity. ‘Be passive, passive and again passive,’ he had told his friend, Tao Zhu, who came to him for advice shortly before his fall.13 He was so cautious that he had actually formulated as a personal guideline the principle, ‘Don't make constructive suggestions’ – on the grounds that anyone who did so would be held responsible for the results. ‘At any given time, in all important questions,’ he told the Ninth Congress, ‘Chairman Mao always charts the course. In our work we do no more than follow in his wake.’

Mao's political antennae were humming for other reasons, too. Since Lin had become his ‘closest comrade-in-arms and successor’, the reclusive Marshal had become more confident – ‘self-important’, in the view of one of his secretaries. Mao had noticed. ‘When [he] farts,’ he said angrily to his staff, ‘[it's] like announcing an imperial edict.’14 Lin's decision to put the army on ‘red alert’ during the crisis with the Russians the previous October had worried him. If nothing else, it had shown how easily control of the PLA could slip from his grasp.15 He had been struck, too, during his travels in the provinces by the number of military uniforms everywhere. ‘Why do we have so many soldiers around?’ he kept grumbling. He knew the reason, of course: it had been his own decision to use the PLA to restore order. But that did not make him like it. Then there was the puzzle of Lin's relationship with the fourth-ranking member of the leadership, Chen Boda. Just before the Ninth Congress, Chen had fallen out with his erstwhile colleagues in the Cultural Revolution Small Group and had transferred his allegiance to Lin and Ye Qun. Mao instinctively mistrusted such alliances.16

Accordingly the Chairman blurred his signals. Instead of issuing a categorical ruling which would have ended the discussion once and for all – as he very easily could have done – he allowed a measure of doubt to subsist.17 That had always been one of Mao's favourite techniques: he placed his colleagues before a situation where they had to make a choice, and then stood back and waited to see which way they would jump.

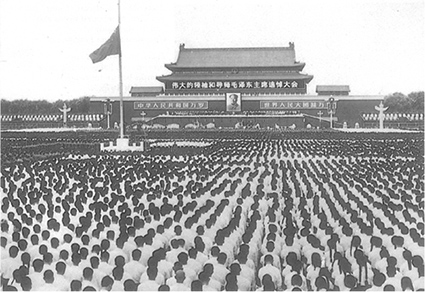

Plate 33 Members of the Politburo Standing Committee in a rare, unposed shot at the ‘7,000-cadre big conference’ in January 1962. From left: Zhou Enlai, Chen Yun, Liu Shaoqi, Mao and Deng Xiaoping.

Plate 34 Swimming in the Yangtse.

Plate 35 Jiang Qing (centre), appearing with Mao in public for the first time in September 1962 to greet the wife of Indonesia’s President Sukarno.

Plate 36 Mao’s propagandist, Yao Wenyuan.

Plate 37 From left: Mao, with Lin Biao, Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De and Dong Biwu during the 1966 National Day celebrations.

Plate 38 In Tiananmen Square, reviewing Red Guards at one of the ten gigantic rallies held at the outset of the Cultural Revolution to encourage China’s youth to rebel.

Plate 39 Magic talisman: the ‘Little Red Book’.

Plate 40 Red Guards giving the yin-yang haircut to the Governor of Heilongjiang at a struggle meeting in September 1966. The placard around his neck labels him ‘a member of the reactionary gang’.

Plate 41 Smashing ancient stone carvings at the Confucian Temple in Qufu, during the campaign against the ‘Four Olds’.

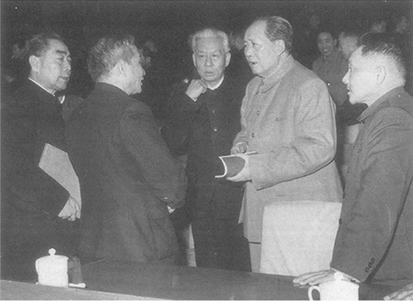

Plate 42 and 43 Top, from left: Lin Biao with Edgar Snow and Mao on Tiananmen during the 1970 National Day celebrations. Eighteen months later, US–China relations had progressed to a point where (below, from right) Henry Kissinger and President Richard Nixon would meet Mao, with interpreter Nancy Tang and Zhou Enlai, at the Chairman’s residence in Zhongnanhai.

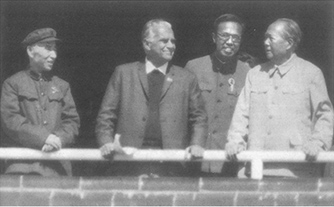

Plate 44 The Chairman’s inner sanctum, dominated by his vast bed, in the Study of Chrysanthemum Fragrance.

Plate 45 Mao with his last companion, Zhang Yufeng, nine months before his death, in December 1975.

Plate 46 and 47 The memorial meeting for Mao in Tiananmen Square on September 18, 1976. Above, from left: Marshal Ye Jianying; Hua Guofeng (reading the eulogy); Wang Hongwen; Zhang Chunqiao and Jiang Qing.

Lin persisted. With his backing, the issue of the state chairmanship was raised again in May, and in July, after which Mao disowned the idea for a fourth time.18

By then, it had become enmeshed in the rivalry between Lin's and Jiang Qing's supporters in the Politburo. In August, this took on a new dimension. Wu Faxian, backed by Chen Boda, proposed writing into the state constitution a reference to Mao having developed Marxism-Leninism ‘with genius, creatively and comprehensively’. Lin had used these terms in his preface to the Little Red Book but the Chairman had forbidden their inclusion in the Party statutes. Wu now argued that it would be wrong to use Mao's dislike of boastfulness in order to minimise the importance of his theoretical contributions. Kang Sheng and Zhang Chunqiao, who had initially objected, were evidently intimidated by this tortured argument and next day the proposal was passed.19

Mao kept his own counsel. The cult of his personality had been an invaluable tool to mobilise the country against Liu Shaoqi. But now that Liu had fallen, it had lost its usefulness. So why was Lin determined to prolong it? To the Chairman's mistrustful mind, the Defence Minister's emphasis on his theoretical ‘genius’ and on Mao Zedong Thought – and his insistence of dignifying him with the title of Head of State – began to look suspiciously like an attempt to kick him upstairs.

There was some basis for this. The original succession plan, under which Mao was to become Honorary Chairman of the Party, had been swept aside when Liu Shaoqi fell. The idea that he should retreat into an elder statesman role, in an honorific capacity as Head of State, must have seemed to Lin a sensible alternative.

It was not something the Defence Minister could propose directly: he knew Mao well enough to realise that any such suggestion, unless it came from the Chairman himself, would be anathema. But Mao's blurred signals made him believe that the concept of an exalted office, to highlight Mao's unique status in China, might in the end prove acceptable – if, indeed, it was not what he had wanted all along. After all, Zhou Enlai had shown that it was sometimes best not to rely on what the Chairman said, but to intuit the way his mind was working and carry on accordingly.

What Lin failed to realise was that Mao had been so badly burned by his first experience of retiring to the ‘second front’ that any hint of a repetition was totally unacceptable.

The result was a massive political misjudgement.

On August 23, 1970, the Defence Minister delivered the keynote speech at a Central Committee plenum at Lushan, the same ill-fated mountain resort where the career of his predecessor, Peng Dehuai, had ended eleven years before.

Mao had approved in advance an outline of what Lin had to say, which included a conventional paean of praise to the Chairman's greatness and a proposal that the new state constitution find an appropriate way of honouring his unique position.20 If he was unhappy that Lin, in his oral remarks, had again used the word ‘genius’, he did not show it. With his agreement, the text was distributed as a conference document.21

Next day, when the plenum divided for group discussions, all Lin's followers made the ‘genius’ issue the main theme of their speeches.

The bombshell, however, was dropped by Chen Boda, who launched into an excited attack on ‘a certain person’, who, he charged, was opposing the use of the term ‘genius’, in a covert attempt to disparage Mao Zedong Thought as the nation's guiding ideology. When other members of the group demanded that he name the guilty party, he indicated that he was referring to Zhang Chunqiao.

From a man of Chen's seniority – with Mao, Lin, Zhou and Kang Sheng, he was one of the five members of the Standing Committee – this was a very serious charge indeed. He then stoked the flames still higher by asserting that ‘certain counter-revolutionaries’ were ‘overjoyed’ at the idea that Mao might refuse the state chairmanship. That caused pandemonium. Chen's group drafted a bulletin, urging Mao to become Head of State with Lin as his deputy, and warning against the activities of ‘swindlers in the Party’ (a reference to Zhang). Such people, it went on, were ‘power-hungry conspirators, reactionaries in the extreme and authentic counter-revolutionary revisionists.’

At one level, this was merely a courtiers’ squabble. Jiang Qing described it later as ‘a literati quarrel’.22 To Mao, however, it had much weightier implications. Chen had rashly launched a factional attack to try to bring down a man whom Mao regarded not merely as his wife's ally but as a key member of his own political camp. Why? And who might be behind it? As delegate after delegate praised Chen's intervention for ‘enhancing their understanding of Vice-Chairman Lin's speech’, it was all too easy to make the connection. Lin's behaviour over the head of state issue had already aroused Mao's suspicions. Now Chen's attack suggested that a conspiracy was afoot.

In fact Chen's diatribe was as much personal as political. He had not forgiven Zhang for Mao's rejection of his draft of Lin's report to the Ninth Congress a year earlier, and had seized on the ‘genius’ issue as a way to get back at his rival. The other members of Lin's group – Wu Faxian, Huang Yongsheng, Li Zuopeng and Qiu Huizuo – had piled in, seeing it as a heaven-sent opportunity to weaken Jiang Qing and her cohorts. However, many of those who joined them, like Wang Dongxing, were Mao loyalists. Yang Dezhi, the Jinan Military Region commander, who had been with the Chairman since the Autumn Harvest Uprising in 1927, wrote later:

Everyone hated Zhang Chunqiao, so we criticised him severely. Zhang Chunqiao was so nervous and frustrated that he smoked one cigarette after another. Every day the ashtray in front of him was filled with cigarette butts. Watching him in such an awkward plight, we were extremely delighted. For the first time since the Cultural Revolution began, we finally got a chance to vent the anger in our hearts.23

That, in Mao's view, was the worst part of all. Lushan in 1970 was turning into a re-edition of Lushan in 1959. Then Peng Dehuai and his supporters had opposed the excesses of the Great Leap Forward. Eleven years later, Chen's attack had shown that many of the delegates to the plenum felt the same way about the Cultural Revolution. Nearly half the members of the Central Committee were military men. The old adage that ‘the Party controls the gun’ was being called into question. Jiang Qing, Zhang Chunqiao and their followers, whatever their failings, could be relied upon to uphold Cultural Revolution policies. With Lin, Mao was no longer quite so sure.24

On the afternoon of August 25, he called an enlarged Standing Committee meeting, at which he accused Chen of violating Party unity. He ordered that discussion of Lin's speech, which had served as the springboard for Chen's action, be terminated. Finally, after six months of uncertainty, he quashed once and for all the idea that he would ever agree to be state chairman.25 A week later, addressing the Politburo, he denounced Chen, who had been at his side since 1937 and had played a pivotal role in promoting his ideas, as a ‘political fraud’ who had ‘launched a surprise attack’, ‘tried to blast Lushan to pieces’ and used ‘rumour-mongering and sophistry’ instead of Marxism-Leninism.26 On Mao's orders, Chen was incarcerated in the Qincheng high security prison, outside Beijing. Two months later, a campaign was launched within the Party, accusing him of being an ‘anti-Party element, sham Marxist, careerist and plotter’.27

In formal terms, Lin emerged unscathed.

Yet the doubts that had been sown in Mao's mind would grow to poison Lin's relationship with the Chairman as insidiously and just as surely as if he had challenged him head on. Mao had no special desire to see his succession plans fall through a second time. He therefore stayed his hand – ‘shielding’ Lin, as he put it later28 – in the hope that the Defence Minister would find a way to retrieve the situation. That was still possible. Lin could have made a self-criticism for promoting the ‘genius’ and ‘Head of State’ issues, while blaming Chen Boda (and, perhaps, Ye Qun) for the factional attack on Zhang Chunqiao. That is what Zhou Enlai would have done and it was certainly what Mao expected. But, whether because he was too confident in his new status as the Chairman's successor, or because of the climate of generalised mistrust existing within the leadership, he did not.

That would turn out to be his second major misjudgement.

In October, when Mao read the written self-criticisms submitted by Ye Qun and Wu Faxian, his attitude hardened. Both had made pro-forma admissions of error, but blamed it on their ‘low level of understanding’. The Chairman vented his irritation in angry marginal comments. Ye Qun, he wrote, ‘refuses to do as I say, but dances immediately when Chen Boda blows his trumpet’; Wu Faxian ‘lacks an open and upright character’.29

At this point Mao began whittling down Lin's power. He described his strategy as ‘mixing in sand, throwing stones and digging up the cornerstone of the wall’.

In November, he added two new members to the Working Group of the CPC Military Commission, which was headed by Wu Faxian (‘mixing in sand’).30 The following month, the Beijing Military Region party committee held a work conference, chaired by Zhou Enlai, at which Chen Boda was labelled a ‘traitor, spy and careerist’ (‘throwing stones’), and the regional commander and political commissar, accused of being Chen's allies, were replaced (‘digging up the cornerstone of the wall’).

However, Mao's misgivings persisted. When, in March, Ye Qun and Wu Faxian produced further self-criticisms, he found them as unsatisfactory as the first. Those eventually submitted by the other three generals, Huang Yongsheng, Liu Zuopeng and Qiu Huizuo, were no better. They had ‘boarded the pirate ship of Chen Boda for so long’, he fulminated, that it had taken them six months to begin to tell the truth.31

In another revealing decision that winter, he dismissed his young partners from the PLA dance troupes, lest they turn out to be Lin's spies.32

Beyond the inner circle, not the slightest hint was allowed to seep out that anything untoward was afoot. Even those closest to Mao, like Zhou Enlai and Jiang Qing, were uncertain how seriously the Chairman was taking Lin's problem.33 Not only to the country at large, but to members of the Central Committee, the Defence Minister was as much his ‘successor and close comrade-in-arms’ as he had ever been.34 Nor did anyone outside the Politburo know that the four generals were in trouble. They retained their posts, and went about their normal duties.

Lin himself seems to have had the keenest intuition of what might lie ahead. By March 1971, he had become morbidly depressed. That month, his 25-year-old son, Lin Liguo, who had a senior post in the air force, began holding secret discussions with a small group of fellow officers on ways of safeguarding Lin's position. The Defence Minister was apparently unaware of these meetings. However, one of the documents the group drew up included a devastatingly accurate assessment of Mao's political tactics which clearly reflected Lin's views:

Today he uses this force to attack that force; tomorrow he uses that force to attack this force. Today he uses sweet words and honeyed talk to those whom he entices, and tomorrow he puts them to death for some fabricated crimes. Those who are his guests today will be his prisoners tomorrow. Looking back at the history of the past few decades, is there anyone he supported initially who has not finally been handed a political death sentence? … His former secretaries have either committed suicide or been arrested. His few close comrades-in-arms or trusted aides have also been sent to prison …35

The group referred to Mao as B52 because, like the US long-range bombers then being used against North Vietnam, he set off explosions from a great height.

Lin Liguo and his colleagues concluded that the Defence Minister's position was not yet under threat, and that the likeliest eventuality was still an orderly succession when Mao died. They examined the possibility of Lin seizing power beforehand, and drew up a rough contingency plan for that purpose, called Project 571 (a homonym for ‘military uprising’). However, the consensus was that this was to be avoided if at all possible because, even if it succeeded, politically there would be ‘a very high price’ to pay.36

None the less, the fact that such discussions were being held at all – even if without Lin Biao's knowledge – testified to a deep malaise within the Defence Minister's camp.

At the end of April 1971, events took a more ominous turn. With Mao's authorisation, Zhou told the four generals and Ye Qun that they were suspected of factional activities and ‘mistakes of political line’.37 Panels bearing Lin's calligraphy in the Great Hall of the People were quietly removed.38 At the same time Mao created a new power base for Jiang Qing and her allies, who were given control of the two key Central Committee departments responsible for propaganda and personnel matters.39

As the year advanced, Lin became more and more withdrawn. He ceased to work and his behaviour was increasingly erratic. On May Day, he pleaded ill-health as an excuse not to attend the celebrations. Zhou persuaded him to change his mind, but when finally he arrived – contrary to protocol, after Mao – the Chairman, irritated by his lateness, ignored him.40 Later that month Mao ordered Zhou to take all the members of the Military Commission Working Group to Beidaihe, where Lin had retired to his seaside villa, to report to him on recent developments. Lin made only one comment: ‘One often harvests what one did not sow’. It is not clear whether Zhou told Mao about that remark: there is some evidence that he tried to protect Lin by claiming that, during the meeting, Lin had criticised the four generals. In any event, soon afterwards, Mao summoned a Central Committee work conference, expecting that Lin would now also make a self-criticism, which might have defused the situation. But the Defense Minister remained obstinately silent.41

At that point, Mao decided that a confrontation could no longer be avoided.

In July he told Zhou Enlai: ‘The [generals’] self-criticisms are nothing but fake. What happened at Lushan is not over, the basic problem is not at all solved. There is a sinister scheme. They have someone behind them.’42 The next month he set off aboard his special train for Wuhan, where he held the first of a series of meetings to canvass support from political and military leaders in the provinces. Everywhere he went, his message was the same: at Lushan, there had been a full-fledged line struggle, in essence identical to the struggles against Liu Shaoqi, Peng Dehuai and Wang Ming. ‘A certain person’, he said, ‘was anxious to become state chairman, to split the Party and to seize power.’ What, therefore, should be done? ‘Comrade Lin Biao’, Mao answered his own question, would have to bear ‘some responsibility’. Some of his group might be able to reform; others would not. Past experience had shown, the Chairman noted drily, that ‘those who have taken the lead in committing major errors of principle, of line and of direction, will find it difficult to reform’.43

It was a measure of how few real allies Lin had in the regional military commands that not until the night of Monday, September 6 – a full three weeks after Mao started his tour – did word reach Beidaihe of what the Chairman had been saying.44

The following six days were utterly surreal.45

Lin himself spent much of his time discussing his children's marriage plans. During the Cultural Revolution, he had asked Xie Fuzhi to organise a search in Beijing and Shanghai for good-looking high-school girls as candidates to wed Lin Liguo – just as, under the Empire, young women of good family had been sought as imperial concubines. Several hundred girls were interviewed, but in the end Liguo had taken as his fiancée a young woman from a PLA dance troupe. A similar search had been undertaken to find a husband for Lin Liheng, Lin Biao's daughter, but Ye Qun had disapproved of her choice and she had tried to kill herself. She, too, was now about to become engaged.

As the Vice-Chairman's political career slipped away from him, it was these family matters that absorbed his attention.

On the afternoon of September 7, Lin Liguo told his sister that Mao was planning to purge their father. ‘It is better for us … to wage a struggle than to wait for our doom’, he said. Liheng was appalled. ‘[Mao] can make the heavens clear and then make them dark again,’ she retorted. ‘He purges whoever he wants to and no one dares struggle against him.’ In response to her questions, her brother said he had not broached any of this with Lin himself, but he thought one possibility was for his father to go to Canton and set up a rival government there. Over the next four days, Liheng repeatedly alerted Lin's security staff that her mother and brother were plotting behind her father's back, but the relationships within the family were so dysfunctional – it was well known that Liheng and her mother hated each other – that no one believed her. On September 8, Liguo returned to Beijing and showed his ‘sworn brothers’ – the small group of fellow officers with whom he had been discussing Project 571 – a note which he said Lin had written that day, enjoining his supporters to ‘act according to the orders of Comrades Liguo and Yuchi’ – a reference to his colleague, Zhou Yuchi. Whether the note was authentic, or whether Liguo forged his handwriting, is not known. But even if Lin did write it, it was so vague that it could have meant anything.

On the basis of Lin's alleged instruction, Liguo and his fellow officers began discussing ways to assassinate Mao. They agreed that the best prospect was to attack his special train.

Various plans were considered – most of them so juvenile they might have come from a child's comic strip: flame-throwers were to be used; or an anti-aircraft gun, aimed to shoot horizontally; an oil depot near the tracks would be blown up; an assassin armed with a pistol would shoot him. Not only was no attempt made to carry out any of these hare-brained schemes, but the conspirators never even reached the stage of making serious preparations.

Appearances notwithstanding, Lin Biao had never been plotting against Mao. Mao was closing in on Lin.

Within hours of Liguo's arrival in Beijing, the Chairman received word of unusual activity at the PLA air-force headquarters. His personal security was reinforced. Soon afterwards, he left Hangzhou for Shanghai. But instead of spending several days there, as had been planned, he received the Nanjing commander, Xu Shiyou, on Saturday morning, and then set out immediately for Beijing, not stopping until his train reached Fengtai, a suburban station on the southern outskirts of the capital, on the afternoon of Sunday, September 12. There he spent two hours with the newly appointed Beijing Military Region Commander, Li Desheng, whom he briefed on much the same lines as he had the provincial commanders in the south.

While Mao was at Fengtai, Lin Biao and a tearful Ye Qun were attending their daughter's engagement party at their residence in Beidaihe.

Lin Liguo, on learning of Mao's precipitate return, held a panic16-stricken meeting with his colleagues, at which they agreed that the best option was for his father to move the following day to Canton. Immediately afterwards he commandeered an air-force Trident to fly to Beidaihe, where he arrived at about 8.15 p.m. just as Mao was returning to Zhongnanhai.

The Defence Minister and his family were to have spent the evening watching films with the newly engaged couple and their friends.

Instead, Lin Biao retired to his room. Liguo told his sister that they were going to have to leave for ‘Dalian or Canton or Hongkong: anywhere depending on the situation’. Soon after, one of Lin's orderlies told her that he had overheard Ye Qun trying to convince Lin to move to Canton, but ‘Lin had remained silent’. Convinced that her mother and brother were trying to manipulate her father, she slipped away to warn the head of the guard unit charged with Lin's security, who this time agreed to report to Beijing. When she returned, Lin had already gone to bed.

By then Zhou Enlai had been called out of a meeting in the Great Hall of the People to take an urgent telephone call. He was told that an air-force jet was at Beidaihe without authorisation, and that, according to Lin Biao's daughter, the Defence Minister was to be taken to an unknown destination, possibly against his will.

Zhou immediately telephoned Wu Faxian and told him to have the plane grounded.

When this news reached Beidaihe. Lin Liguo and Ye Qun realised that the game was up. It may have been then that they decided to make straight for the nearest border – which meant heading north, towards Mongolia and Russia. Whether Lin himself was aware of the new plan is not known: he was under strong medication and in any case had already taken his sleeping pills. In an attempt to disarm suspicion, Ye Qun telephoned the Premier to inform him that they were planning to move next day to Dalian. At midnight, Lin Biao's armoured limousine pulled away from their residence, sped past a cordon of guards and headed for the airport. On the way Lin's chief bodyguard leapt from the moving vehicle and was shot and wounded.46

Despite Zhou's order, the Trident had been refuelled. Lin, Ye Qun, Lin Liguo, another air-force officer and their driver clambered aboard, and at 12.32 a.m. on Monday, September 13, with its navigation lights turned off and the airport in total darkness, the aircraft took off.

Zhou ordered a total ban on aircraft movements throughout China, which remained in force for the next two days. He then reported to Mao.

One of the many unresolved questions surrounding Lin Biao's flight is why the central Guard Unit, which answered to Wang Dongxing, made no attempt to stop them. Lin Liheng told the unit's Beidaihe commander, Zhang Hong, at about 9.15 p.m. that her mother and brother were forcing Lin to make a precipitate departure. For the next three hours, the unit – apparently on instructions from Beijing – refused to intervene. At one point, Zhang told Liheng that ‘the Centre’, which she took to mean Mao, wanted her to accompany Lin and the rest of the family when they left. She never found out why. Another mystery concerns Mao's role during the crucial hour between Zhou Enlai informing him, probably some time after 11pm, of the events at Beidaihe, and the aircraft's departure just after 12.30 a.m. Nothing is known of his reactions until after the plane had taken off, when Wu Faxian telephoned Zhou in his presence to say that it was heading for Mongolia and to ask whether it should be shot down. Mao was said to have responded philosophically: ‘The skies will rain; widows will remarry; these things are unstoppable. Let them go.’47

At 1.50 a.m. the aircraft left Chinese airspace.I

Mao moved, for security reasons, to the Great Hall of the People, where, at 3 a.m., the Politburo convened, to be informed of his return to the capital and the sensational news of Lin's flight.

Thirty hours later, Zhou was awakened to be handed a message from China's Ambassador in Ulan Bator. The Mongolian Foreign Ministry had issued an official protest because a Chinese air-force Trident had violated Mongolian airspace in the early hours of Monday morning, and had crashed near the settlement of Undur Khan. All nine people on board had been killed. The bodies were identified by Soviet forensic experts and buried nearby.

An examination of the site showed that the plane had overturned and caught fire while trying to make an emergency landing in the steppe. Flying at low altitude, it probably ran out of fuel. Yet here, too, one final mystery remains. Shortly before the aircraft had taken off, Wu Faxian had telephoned the control tower at Shanhaiguan and had given the pilot, Pan Jingyin, a direct order not to fly under any circumstances. Pan assured him that he would not. Minutes later, the plane left, flying at a height of 300 metres to try to avoid radar and observing radio silence. That would normally make Pan an accomplice in Lin's betrayal. Yet he was posthumously decorated as a revolutionary martyr. Could he have been in some way responsible for the crash, and hence for foiling Lin's escape, and if so, could Beijing have learned what he had done? There is no answer.

Of all the Chinese leaders Mao purged during his years of power, only Lin Biao attempted to resist. Peng Dehuai and Liu Shaoqi had gone meekly to their fates, maintaining to the last their unswerving devotion to the Party. Neither had attempted to defend himself; neither tried to hit back. Even Gao Gang, who made a kind of protest by committing suicide, had first confessed his errors.

Lin was different. He had employed what Mao called the ‘last and best’ of the ‘36 stratagems’ from the military manuals of Chinese antiquity: to run away. He had not abased himself. Nor had he submitted to Mao's will.

The Chairman was shattered.

His doctor, who was present when Zhou broke the news of Lin's flight, remembered years later how his face collapsed in shock.48 Once the initial crisis had passed, and the Defence Minister's allies – including the four unfortunate generals, Wu Faxian, Lin Zuopeng, Qiu Huizuo and Huang Yongsheng, who had been as much in the dark as everyone else – had been placed under arrest, Mao took to his bed, suffering from deep depression. He remained there for nearly two months, with high blood pressure and a lung infection. As ever, it was psychosomatic. But this time, he did not bounce back. In November, when he emerged to meet the North Vietnamese Premier, Pham Van Dong, Chinese who saw the television pictures were shocked at how much he had aged. His shoulders were stooped, and he walked with an old man's shuffle. People said his legs looked like wobbly, wooden sticks.

In January 1972, Chen Yi died. Two hours before the funeral, Mao decided that he would attend, disregarding the entreaties of his aides who feared that the subzero weather would be too much for his frail health. They were right. After standing through the ceremony, Mao's legs were trembling so badly he could barely walk.

It was widely rumoured afterwards that that month he had a stroke. In fact he suffered from congestive heart failure, which he made worse by refusing medical treatment.49 But the root of the problem remained political. Although Mao had been preparing, in August and early September, for a confrontation with Lin Biao, he had not decided exactly how the problem should be resolved: whether simply to demote him within the Politburo; to criticise him inside the Party, but allow him to remain a nominal member of the leadership, like Peng Dehuai in 1959; or to purge him altogether – a possibility, given careful preparation, but the least desirable option because of its effect on public opinion. By fleeing, Lin Biao had taken the initiative out of the Chairman's hands.50

In one sense, his task was made easier by the discovery of the activities of Lin Liguo.

Although Mao had sensed a security risk, and had taken precautions accordingly, details of the young air-force officers’ plotting had emerged only after Lin's flight. Juvenile though the conspiracy was, it enabled Mao to paint the Defence Minister as a traitor, who had attempted to stage a coup d'état.

This was the line pursued in briefings to Party officials which began in mid-October, to be followed by meetings in factories and work units to inform the population at large.51

It was not an easy story to sell. Even the credulity of the long-suffering Chinese was strained by the revelation that yet another of Mao's closest colleagues had proved to be a villain. What did it say about the Chairman's judgement if Liu Shaoqi (a ‘scab and renegade’), Chen Boda (a ‘sham Marxist’) and Lin Biao (a ‘counter-revolutionary careerist’), all of whom had been at Mao's side for decades, were suddenly, one after the other, unmasked as hidden enemies? The ‘Hundred Flowers’ and the anti-Rightist Campaign had cost Mao the trust of China's intellectuals. The chaos and terror of the Cultural Revolution had destroyed the faith of the Party hierarchy and tens of millions of ordinary citizens. Lin Biao's fall was the last straw. After 1971, general cynicism prevailed. Only the young (and not all of them), and those who had profited from the radical upsurge, still believed in Mao's revolutionary new world.

The combined effects of illness and political failure brought the Chairman close to despair. For the first time since the autumn of 1945, when Stalin had betrayed him in the confrontation with Chiang Kai-shek, he felt like giving up. One afternoon in January 1972 he told an appalled Zhou Enlai, whom he had placed in charge of the day-to-day work of the Central Committee, that he could no longer carry on and Zhou should take over.52 In 1945 it had had been an American, Harry Truman, who had lifted Mao's depression by launching the Marshall mission to mediate in the Chinese civil war. This time, too, an American would get him out of his black hole. For Mao, and for the Chinese people, the fate of Lin Biao was soon to be eclipsed by an even more astonishing and unthinkable event: after twenty years of unblinking hostility, the US President, Richard Nixon, was to pay an official visit to Beijing.

The clashes on Zhenbao Island in March 1969, and the tension between Beijing and Moscow the following spring and summer, had certainly got Washington's attention. Even beforehand, some US leaders had begun to think aloud about a more productive relationship with Beijing. A year or so earlier, Nixon had written of the need to wean China from its ‘angry isolation’, a phrase which he had repeated in his inaugural address. There had been talk of trying to move towards a triangular relationship. But until the border conflict raised the spectre of a Sino-Soviet war, no one could see how that might be done.53

The first hesitant signals began in July that year. The United States modified its ban on American citizens travelling to China. Three days later, China released two American yachtsmen who had strayed into Chinese waters. In August, the Secretary of State, William Rogers, stated publicly that the US was ‘seeking to open up channels of communication’. Romania and Pakistan were asked to relay private messages. In October, as Sino-Soviet tensions eased, Nixon made a more substantial gesture: the Chinese were informed that two US destroyers, which had been making symbolic patrols in the Taiwan Straits since the Korean War, were to be withdrawn.

So began what Kissinger called an ‘intricate minuet’, which twenty-one months later would make him the first US official to travel to Beijing since 1949.

Along the way there was farce: when Walter Stoessel, the US Ambassador in Warsaw, approached his Chinese counterpart at a reception to express interest in talks, he watched his interlocutor back away and run down a staircase, terrified of a contact for which he had no instructions. There was tragedy: an American businessman, who had spent fifteen years in Chinese prisons as a spy, committed suicide shortly before he was to have been released as a gesture of goodwill. There were setbacks: contacts virtually stopped for six months in 1970 because of the US offensive in Cambodia. And there was bafflement: on National Day in Beijing that year, Zhou Enlai brought Edgar Snow and his wife, who were then visiting China, to be photographed with Mao on Tiananmen. It was an unprecedented gesture: no foreigner had ever been so honoured. ‘Unfortunately,’ Kissinger confessed later, ‘what they conveyed was so oblique that our crude Occidental minds completely missed the point.’ Only long afterwards did he realise that Mao was signalling that the dialogue with America had his personal support.

Mao's elliptical way of doing things soon defeated his purposes a second time. In an interview with Snow in December, he alluded to Nixon's remark, two months earlier, that ‘if there is anything I want to do before I die, it is to go to China’. Mao told Snow: ‘I would be happy to talk with him, either as a tourist or as President.’ Afterwards, Snow was given the official Chinese transcript of the conversation, but asked to delay publication for several months. Mao's assumption was that Snow would send a copy of the transcript to the White House. He did not – and again the Chairman's message did not get through.54

The following spring, therefore, Mao made a gesture which even the obtuse Americans could not fail to understand.

In March 1971, a Chinese table-tennis team participated in the World Championships in Nagoya, Japan. They were the first Chinese sportsmen to travel abroad for years. On April 4, one of the US team taking part, a nineteen-year-old Californian, mentioned casually to a Chinese player that he would love to visit Beijing. This was reported back to Zhou Enlai, who raised it with Mao next day. They agreed not to pursue it. But that night, after taking his sleeping pills, Mao called his head nurse and told her drowsily, just before he fell asleep, to telephone the Foreign Ministry with instructions to invite the American players at once.II

Ping-pong diplomacy, as it was called, took the world by storm.

The US players were given a dazzling welcome. Zhou himself received them in the Great Hall of the People, and declared that they had opened a new chapter in the two countries’ relations which marked a ‘recommencement of our friendship’.

Three months later, Kissinger followed. His journey was kept secret – thanks to a subterfuge about a stomach upset which supposedly confined him to bed in Pakistan. On his return, an exuberant Nixon announced on American television that a high-level dialogue with China was under way and he himself would go there next spring. To flesh out the details, Kissinger returned to Beijing in October – this time in the full glare of publicity – and agreed the basis for the Shanghai communiqué, which was to be the crowning achievement of the presidential visit, fixing the pattern of Chinese–US relations for the rest of the century and beyond.

Mao was preoccupied with the Lin Biao affair during Kissinger's first trip, and bedridden, suffering from depression, during the second. None the less, it was his caustic instruction that the two sides avoid ‘the sort of banality that the Soviets would sign, but neither mean nor observe’ that gave the communiqué its force. Differences were stated ‘explicitly, sometimes brutally’, which underlined their common interest in opposing Soviet hegemony.55 Only the crucial issue of Taiwan remained wrapped in ambiguity.

The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China, and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States does not challenge that position. It reaffirms its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves.56

As Kissinger left for home at the end of this second visit, the United Nations General Assembly voted to expel Taiwan and seat the People's Republic in its place. An era in post-war politics was over.

By January 1972, the diplomatic preparations for Nixon's trip had been completed.

But the central personage of the drama was missing. Mao's physical condition was deteriorating, and he was still refusing to allow his doctors to treat him. On February 1 – three weeks before Nixon was due to arrive – he relented, only to collapse, unconscious, next day after choking on phlegm from his infected lungs. A combination of antibiotics and the prospect of meeting China's ‘most respected enemy’ pulled him back from the brink. However, his throat remained swollen, making it difficult for him to talk, and his body was so bloated from the build-up of fluid that a new suit and shoes had to be made. In the week before Nixon arrived, his staff helped him to practise sitting down, getting up and walking about in his room, to exercise his muscles again after the months he had spent confined to his bed.57

When the great day came, Mao was on tenterhooks. He sat by the telephone listening to minute-by-minute reports of the President's progress from the airport, where he had been greeted by Zhou Enlai; through the empty streets of Beijing, cleared of traffic for the occasion; to the state guest-house at Diaoyutai. No meeting with Mao was on the schedule. But he now sent word that he wanted to see the President at once. At Zhou's insistence, Nixon was allowed to rest and have lunch. But then he and Kissinger were swept off in a cavalcade of Red Flag limousines to Zhongnanhai, where Mao was impatiently waiting. In his memoirs, Kissinger gave an awed description of the scene that met them:

[In] Mao's study … manuscripts lined bookshelves along every wall; books covered the table and the floor; it looked more the retreat of a scholar than the audience room of the all-powerful leader of the world's most populous nation … Except for the suddenness of the summons, there was no ceremony. Mao just stood there … I have met no one, with the possible exception of Charles de Gaulle, who so distilled raw, concentrated will power. He was planted there with a female attendant close by to help steady him … He dominated the room – not by the pomp that in most states confers a degree of majesty on the leaders, but by exuding in almost tangible form the overwhelming drive to prevail.

Nixon's account was more matter-of-fact. But he, too, was bowled over by what Kissinger called, in words almost identical to those Sidney Rittenberg had used at Yan'an, thirty years earlier, ‘our encounter with history’.

Mao took Nixon's hand in both his own and held it for almost a minute.

One of them presided over the citadel of international capitalism, backed by the strongest economy and military forces in the world; the other was uncontested patriarch of a revolutionary communist state of 800 million people, whose ideology called for the overthrow of capitalism wherever it might appear.

The photograph in the People's Daily next day told China, and the world, that the global balance of power had been transformed.

Their talks lasted over an hour, far longer than the brief courtesy call that had initially been planned. Mao startled Nixon by telling him that he preferred dealing with right-wing leaders because they were more predictable. Nixon emphasised that the biggest threat they both faced came not from each other but from Russia. Kissinger, ever the diplomatist, was struck by Mao's deceptively casual conversation, embedding his thoughts in tangential phrases which ‘communicated a meaning while evading a commitment … [like] passing shadows on a wall’. Zhou worried about Mao getting tired. Nixon had been told that the Chairman was recovering from bronchitis, and after Zhou had looked at his watch several times, the President brought the meeting to a close.

After that, everything else was anticlimax. Nixon and Zhou laboured over the nuts and bolts of the Chinese–American relationship. But the tone had already been set.

To Mao, Nixon's visit was a triumph. Others, whose nations’ historical role in China was not less, would soon follow: Kakuei Tanaka, to establish diplomatic relations with Japan; the British Prime Minister, Edward Heath. But nothing would ever again in Mao's life equal the moment when the leader of the Western world came to the Forbidden City bearing in tribute a shared concern about a common enemy. In 1949, Mao had argued that China should not be in too much of a hurry to establish ties with the Western powers – that it should complete its ‘house-cleaning’ first, and then determine, at a time of its own choosing, which countries it wished to admit. For years, as Western leaders sought to isolate Red China, that had seemed a hollow excuse. But now the first among them had come to Beijing, seeking co-operation on a basis of equality. China had indeed stood up. It was a moment to savour.

Yet it also marked a massive retreat.

Nixon had put his finger on it in an article he wrote a year before his election. The United States, he said, needed to engage with China, ‘but as a great and progressing nation, not as the epicentre of world revolution’.58 That was indeed what happened. In opening the door to America, Mao had responded to geopolitical necessity – the need for a common front to contain the expansionist impulses of Russia. There were moments of doubt. Mao fretted that the Americans,59 ‘whether purposely or not’, might stand aside while the Russians attacked China: ‘Let them get bogged down … And then you can poke your finger at the Soviet back.’ But the bottom line was, as he put it: ‘We can work together to deal in common with a bastard.’ The price of that cooperation was the abandonment of his vision of a new Red ‘Middle Kingdom’ from which the world's revolutionaries would draw hope and inspiration. In its place came cold-eyed balance-of-power politics aimed at guaranteeing not revolution but survival.

At his meeting with Nixon, Mao acknowledged this himself. ‘People like me sound like a lot of big cannons,’ he said. ‘For example, [we say] things like “the whole world should unite and defeat imperialism …”’ – at which point he and Zhou laughed uproariously.60

Mao could rationalise such statements by his usual argument that all progress stemmed from contradictions, and that there could be no advance without retreat. None the less, retreat it was. Another of his favourite themes of the 1960s – the notion that China, by the force of its example, would spur a worldwide revolutionary upsurge – had been irredeemably compromised.

The collapse of Mao's plans for his succession and the eclipse of revolutionary by geopolitical concerns were not the only holes being punched into the Cultural Revolution and its policies.

In the autumn of 1971, when Mao toured central China to rally support among the provincial military commanders, he had complained that veteran cadres who had been unjustly purged had still not been rehabilitated.61 The following November, two months after Lin Biao's death, he said the denunciation of the marshals and others involved in the ‘February Adverse Current’ had been wrong; they had merely been ‘opposing Lin Biao and Chen Boda’. At Chen Yi's funeral in January 1972, he gave further signs of distancing himself from the attacks on the old guard. Later that year he condemned the persecution of He Long as ‘a false case’.62

Encouraged by these developments, Zhou Enlai began a full-scale effort to rebuild the administration and restore economic production.

He was in a stronger position than he had been for many years. The factional clashes which had disrupted transport and industry had finally been brought to an end. Of the five members of the Standing Committee, Lin was dead; Chen Boda was in prison; and Kang Sheng had cancer. That left just him and Mao. In one sense this was dangerous: Mao had a record of turning against those who got too close to him. Zhou was well aware of the risk that such proximity entailed.63 Shortly after Lin Biao's demise, Ji Dengkui, finding him deeply depressed, had tried to lift his spirits. ‘You don't understand,’ Zhou had burst out. ‘It's not finished!’ Somewhere down the road, the struggle for Mao's succession would have to start all over again.III For the moment, however, even disregarding the Chairman's anguished outburst from his sickbed, asking him to take over, the tide was running vigorously in the Premier's favour. The disgrace of Lin Biao had put Jiang Qing and her fellow radicals on the defensive. China's admission to the United Nations and the Nixon visit had shown that pragmatic policies brought results. Zhou's discovery, during a routine medical check-up in May, that he, too, was suffering from cancer, simply made him more determined.64 He knew now that this was the last chance he would have to place his own seal on China's progress – to nudge the country on to a path of orderly, balanced development that would assure its people a better and happier future.

The Premier's strategy was to use the movement against Lin Biao – officially known as the ‘campaign to criticise revisionism and rectify working style’ – for an all-out offensive against ultra-Leftist policies and ideas. In April, the People's Daily fired the opening salvo, describing veteran cadres as ‘the Party's most treasured possession’ and urging that they be rehabilitated and given appropriate positions.65 Chen Yun, the doyen of old-guard economists, reappeared in public (although, prudently, he pleaded that his poor health would not permit him to resume work).66 Expertise was emphasised again. A Beijing radio station began broadcasting English-language lessons. For the first time since 1966, China sent students abroad.67 Zhou criticised the Foreign Ministry for failing to change its Leftist ways, using the ingenious argument that unless ultra-Leftism were denounced, Rightism would surely re-emerge.68

But even a thicket of straws in the wind could not hide the fact that Mao had conspicuously refrained from giving Zhou public support.69 Pragmatism abroad was one thing. Demolishing Cultural Revolution policies at home was another. In December 1972, the Chairman decided that the pendulum had swung too far.

The trigger was a page of articles which had appeared in the People's Daily two months earlier condemning anarchism. The themes it raised were familiar: the persecution of veteran cadres, the trashing of the role of the Party, the waste and destruction of the ‘great chaos’ – which the newspaper blamed on ultra-Leftism. But cumulatively the articles called into question all that the Cultural Revolution stood for. Zhou's supporters on the paper then proposed a campaign on the theme that ‘the right is bound to return unless we thoroughly denounce the Left’. At that, Mao put his foot down. On December 17, he ruled that Lin's errors, while ‘Left in form’, were ‘right in essence’, and that Lin himself had been an ultra-Rightist, who had plotted conspiracies, splits and betrayal. Criticising ultra-Leftism was ‘not a good idea’.

Two days later Zhou Enlai showed the stuff of which he was made.

He repudiated his previous statements, echoed Mao's revised view of Lin, and cast his unfortunate allies at the People's Daily to the wolves.70

From then on, the campaign underwent a sea change. Where Zhou had tried to use it as a lever to undo Cultural Revolution policies, the radicals made Lin a scapegoat for the movement's excesses. The new line was spelt out in a New Year's Day editorial, which commended the Cultural Revolution as ‘much needed and very timely for consolidating the proletarian dictatorship, preventing capitalist restoration and building socialism’.71

However, the Chairman was not about to reverse himself completely.

The pendulum might have swung too far. But there was a limit to the extent it would be allowed to swing back. At Mao's insistence, the rehabilitation of veteran cadres continued. The last four years of his life would be taken up with an effort, so inherently contradictory that it was almost schizophrenic, to maintain an unstable balance between his radical yearnings and the country's all too evident need for a more predictable, less tortured future.

The conflict played out, as Zhou had anticipated it would, over the succession.

In 1972, when Mao contemplated the ruins left by Lin Biao's defection, he had few options. Zhou Enlai – moments of panic apart – was too old, too moderate and, in the final analysis, too weak, to be considered a possible heir, and in any case he adamantly rejected the idea. Moreover, as Wang Ruoshui, the scholarly People's Daily editor who had been responsible for the October articles, concluded after the December 17 decision, deep down Mao did not like Zhou. Jiang Qing was a loyal radical but, as Mao well knew, she was almost universally detested – greedy for power, haughty, vain and incompetent. Yao Wenyuan was a propagandist, no more able to command others than a man like Chen Boda. Among the younger Politburo members, the only possible candidate was Zhang Chunqiao. He was fifty-five years, old. His fidelity to the Cultural Revolution was unquestioned. He had proven qualities of leadership. Mao had even once mentioned him as a potential successor to Lin.

But Mao did not choose Zhang Chunqiao.

Instead, in September 1972, he summoned from Shanghai one of Zhang's deputies, Wang Hongwen, whose Workers’ General Headquarters had engineered the Cultural Revolution's first ‘seizure of power’ almost six years before.

Wang, now a Central Committee member, was a tall, well-built man, who, at the age of thirty-nine, retained some of the earnestness of youth. He came from a poor peasant family; had fought in the Korean War; and afterwards had been assigned to a textile mill. To Mao, that meant he combined the three most desirable social backgrounds – peasant, worker and soldier. He was not told why he had been brought to the capital, and was mystified when the Chairman in person received him and plied him with questions about his life and views. Evidently he passed with flying colours, for Mao set him to studying the complete works of Marx, Engels and Lenin – a task far beyond his meagre educational accomplishments and which he found excruciatingly boring. He also found it hard to adjust to Mao's night-owl work habits and made homesick phonecalls to his Shanghai friends, complaining how tedious life was.72 None the less, at the end of December, two days after Mao's seventy-ninth birthday, Zhou Enlai and Ye Jianying introduced him at a conference of the Beijing Military Region Party Committee as ‘a young man the Chairman has noticed’, adding that it was Mao's intention to promote people of his generation to vice-chairmanships in the Central Committee and the Military Commission.73

This was not mere caprice on Mao's part. Liu Shaoqi and Lin Biao had both had the stature to carry the whole Party with them. Zhang Chunqiao did not. He was too deeply involved in radical factionalism (and perceived as being too close to Jiang Qing) to command the loyalty of the Party mainstream, and too sectarian in his attitudes to work together with moderate leaders who could.

Wang was an outsider, a dark horse, who, because he had been far from the capital, was not tarred with the same factional brush.

In May 1973, he began the next stage of his apprenticeship in power when, on Mao's instructions, he started attending Politburo meetings. So did two other neophytes: Hua Guofeng and Wu De. Hua had first caught Mao's eye in the 1950s as Party Secretary of the Chairman's home county of Xiangtan. After the Cultural Revolution he had been appointed First Secretary of the Hunan Provincial Party Committee before moving to Beijing as a member of the commission investigating the Lin Biao affair. Wu De had succeeded Xie Fuzhi as First Secretary of the Beijing Party Committee following Xie's death from cancer. Both were older than Wang: Hua was fifty-one; Wu, sixty. Like him, both had been beneficiaries of the Cultural Revolution yet were sufficiently middle-of-the-road to build support across factional lines. They were there as a backstop, in case Mao's primary strategy should miscarry.

That left just one more piece of the puzzle for the Chairman to put into place.

On April 12, a short, stocky man with a bullet head and slightly greying hair attended a banquet for the Cambodian Head of State, Prince Sihanouk, in the Great Hall of the People, looking as though he had never been away. Deng Xiaoping, the ‘number-two Party person in authority taking the capitalist road’, had been quietly rehabilitated a month earlier to resume work as a vice-premier.74

Deng was then nearly sixty-nine years old, almost twice Wang Hongwen's age. His return had been prompted partly by Zhou's cancer, which had made it urgent to find an understudy, and partly by a shrewdly worded appeal, which he had sent the Chairman the previous August, praising the Cultural Revolution as ‘an immense monster-revealing mirror’ that had exposed swindlers like Lin Biao and Chen Boda (and mentioning, in passing, that he would like to get back to work himself). Astutely he had also given undertakings never to ‘reverse verdicts’ on the Cultural Revolution, and never to attack Jiang Qing.75 But the fundamental reason for Deng's reinstatement was Mao's awareness that Wang would not be able to assume the succession without help. The Chairman's grand design was that they should work together, Wang heading the Party and Deng the government, until the younger man acquired the knowledge and experience, ten or fifteen years down the road, to run China on his own. Deng had the prestige to keep the army in check; Wang, Mao knew very well, did not. Deng had the ability to keep the administration turning; Wang, again, did not. But if Wang could be established before Mao died as the inheritor of his Party mantle, his youth and commitment to Cultural Revolution values looked like being the Chairman's best hope of ensuring that his ideological legacy would outlive him.

With this aim in view, Wang was given a starring role at the Tenth Party Congress, an oddly abbreviated, ritualistic gathering, held in total secrecy in the Great Hall of the People from August 24 to 28.IV He chaired the Election Committee, with Zhou Enlai and Jiang Qing as his deputies; he introduced the new, revised Party constitution (eliminating the reference to Lin Biao as Mao's successor); he placed Mao's ballot in the voting urn, when the Chairman was too frail to do so himself – a symbolism which was not lost on those present; and, in the new Politburo, to the astonishment of Party and non-Party members alike, he took third place in the hierarchy, behind Mao himself and Zhou, with the rank of Vice-Chairman.76

Deng was restored to the Central Committee – though not, at that stage, to the Politburo. For the moment he was on probation: the Chairman wanted to see how he would behave before promoting him further.

The Congress also put flesh on the bones of Mao's new formula of having a mix of radicals and veteran cadres to rule China after his death. In the Politburo and the Standing Committee, there was an approximate balance between Jiang Qing's group, on one side, and the old guard, headed by Zhou Enlai and Ye Jianying, on the other. As well as Deng, a number of other prominent veterans were re-elected to CC membership, including Tan Zhenlin, who had fallen foul of Jiang Qing at the time of the ‘February Adverse Current’; the Inner Mongolian leader, Ulanfu, who had survived a regional purge in which tens of thousands of his followers had been killed and injured; and Wang Jiaxiang, Mao's early supporter at Zunyi, who had fallen foul of the Chairman by advocating moderation towards the United States and Russia in the early 1960s.77

That autumn, Mao sent Deng and Wang Hongwen on a tour of the provinces to see how they could work together. On their return, Deng told him, with characteristic bluntness, that he saw a risk of warlordism. Twenty-two out of the twenty-nine provincial Party committees were headed by serving army officers.78

Mao had reached the same conclusion. At the 10th Congress the number of military men in the Central Committee had been halved. Now, in December 1973, he ordered a reshuffle of the commanders of China's eight military regions. He told the Politburo and the Military Commission that in future there must be a clearer division of responsibilities between military and political work, and that Deng, whom he described as ‘a man of rare talent’, should from now on participate in meetings of both bodies, while also assuming the duties of Chief of the General Staff.79

The following April, Mao chose Deng to lead the Chinese delegation to the United Nations, where he unveiled the Chairman's latest thoughts on international affairs, the so-called ‘Three Worlds’ theory, under which the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, were viewed as the ‘first world’; the other industrialised nations, communist and capitalist alike, as the ‘second world’; and the developing countries as the ‘third world’.80

Two months later, when a very sick Zhou Enlai entered hospital for long-term cancer treatment, Mao designated Wang Hongwen to take day-to-day charge of the work of the Politburo and Deng to head the work of the government.

Thus, by June 1974, the Chairman had put in place the political partnership that he hoped would continue his work after him. It was all still highly provisional. Deng had returned to the Politburo just six months earlier. Wang existed politically only because Mao had created him. Yet it seemed that a consensus, however fragile, was finally being established for the orderly succession which had eluded Mao twice before.

Once again it would turn out to be a house of cards.

The fatal flaw in the logic of Mao's arrangements came from the tension inspired by his contradictory impulses towards radicalism and reason. As long as he himself had the whiphand – as he did in 1973 and 1974 – the rival halves of the leadership that mirrored this ideological conflict could be made to work together in an uneasy coalition. But as his strength ebbed away, his physical weakness meant that he was less often present to impose his authority and the two groups grew into warring factions.

Instead of dominating this struggle, as Mao had hoped, Wang and Deng were both sucked into it.

As so often, it was Mao himself who chose the terrain. In May 1973, he had proposed to a Central Committee work conference a campaign to criticise Confucius (who had, of course, died 2,500 years earlier). The pretext was that Lin Liguo had likened Mao to Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of Qin, who had ‘burned the [Confucian] books and buried the scholars alive’. Mao generally welcomed that comparison. In a poem that autumn, he had assumed the mantle of Qin Shihuang's successor:

The business of burning and burying requires discussion;

Although the ancient dragon is dead, his empire lives on,

While the lofty frame of Confucianism is but chaff.81

Lin Biao and his followers, he charged – since they opposed Qin Shihuang – were supporters of Confucius, and therefore of the feudal landlord system that the Sage had extolled in his writings. But the campaign had more than one layer of meaning. By associating Confucius with Lin Biao, Mao was playing the old game of ‘pointing at the locust tree in order to revile the mulberry’. The true target of the new movement was neither Confucius nor Lin Biao, but Zhou Enlai, whose efforts to repair the damage caused by the Cultural Revolution were causing the Chairman growing concern. At the Tenth Congress, the Revolution's shortcomings, which by his usual rule of thumb Mao had estimated at 30 per cent, were all but forgotten. The emphasis was on preserving the 70 per cent of achievements.82 The Party constitution which the Congress approved stated that new Cultural Revolutions ‘will have to be carried out many times in the future’ and quoted Mao's warning that ‘every seven or eight years monsters and demons will jump out [again]’.

The connection between Confucius and Zhou was never openly admitted. However, Mao had dropped a broad hint at a meeting with Wang Hongwen and Zhang Chunqiao that summer, when he reiterated the need to criticise Confucius while, almost in the same breath, grumbling that the Foreign Ministry was not discussing ‘important matters’ with him, and that if this continued, ‘revisionism is bound to occur’. The Ministry was Zhou's responsibility. It was there, a year earlier, that the Premier had spoken out against ultra-Leftism. Mao had not forgotten. From June onwards, both the radicals and Mao himself kept up a drumbeat of criticism of Zhou's handling of foreign affairs.83

Their attacks, coming on top of the Premier's illness, sapped his strength. When Kissinger came to Beijing, on his sixth visit to China in November 1973, he found Zhou ‘uncharacteristically tentative’. The old bite and sparkle were missing. During their discussions on Taiwan, Kissinger wrote later, he sensed, for the first time, a willingness to envisage the normalisation of US–Chinese relations without a formal rupture between Washington and Taibei (an impression which he felt was confirmed when he met Mao the following day).84 In fact, Kissinger was mistaken. Mao's message, elliptical as ever, was that while the Soviet Union might accept that kind of arrangement, China would not.85 Zhou did, however, indicate that a peaceful settlement with Taiwan was not ruled out, and there was also discussion of the possibility of setting up a hotline between Washington and Beijing to give early warning of any future Soviet missile attack against China. None of that was especially contentious but, for whatever reason, the Chairman seized on it as a pretext to step up the pressure on Zhou. He may have been irritated that Zhou had discussed closer military cooperation with the United States without first seeking his approval; he may have found Zhou's remarks on Taiwan too conciliatory; or he may simply have been looking for new grounds to voice the dissatisfaction that had been festering since Zhou's campaign against ultra-leftism a year earlier. It is possible, too, that jealousy played a part. Mao was unhappy that foreigners gave Zhou most of the credit for the Nixon visit and the Sino-American rapprochement which had followed.

The day Kissinger left, the Chairman ordered Zhou to convene a Politburo meeting and explain himself. Jiang Qing accused the Premier of ‘right-deviationist capitulationism’, a charge which he rejected. He did admit, however, to ‘not having done enough’ in the negotiations with Kissinger and to errors of ‘revisionist thinking’. For the next three weeks Zhou was subjected to daily criticism at enlarged meetings of the Politburo which lasted well into December. Mao himself orchestrated the proceedings and ensured that not only the radicals but Zhou's ostensible allies, including Deng Xiaoping, took part in the assault. The Premier was accused of creating an ‘independent kingdom’ in the Foreign Ministry, of betraying the country and even of being willing to serve as a ‘puppet emperor’ if the Soviet Union invaded. He was ‘too impatient to wait to replace Chairman Mao’, Jiang claimed – a singularly absurd allegation against a man in an advanced stage of cancer – and a full scale line struggle should be waged against him, similar to those against Liu Shaoqi and Lin Biao.

At that point, Mao intervened, telling Zhou and Wang Hongwen that the only person impatient to replace him was Jiang Qing herself. Zhou had made errors, he said, but he would be allowed to make a self-criticism. Mao had suggested that if he spoke for ‘40 or 50 minutes’, that would be enough. Zhou proceeded to make a grovelling penance which lasted seven hours.86

Soon afterwards the Premier relinquished responsibility for foreign affairs (which passed to Deng Xiaoping),87 and in January 1974 the campaign to ‘criticise Lin Biao and Confucius’, which until then had been confined to academic discussions among Party theorists, was launched as a full-fledged national movement. To Mao, its purpose was to combat revisionism and protect the Cultural Revolution's achievements. To Jiang Qing and her radical allies, it was a means of undermining the Premier – and thus of strengthening their chance to play a major role in the leadership after Mao's death.88

The campaign itself was a welter of far-fetched historical allegory and innuendo, accompanied by petty attacks on Zhou's policies – based on symbolic incidents, such as a student handing in a blank examination paper to protest against the new emphasis on academic standards – under the rubric of ‘going against the tide’. The aim was to foment a new surge of unrest, in the same way as Mao's statement, ‘It is right to rebel’, had mobilised the Red Guards seven years earlier. Wang Hongwen called it, more in hope than expectation, ‘a second Cultural Revolution’, and Zhang Chunqiao, ‘a second seizure of power’.89 In fact very little power was seized and policy remained essentially unchanged. The population at large and the political rank and file were already weary of the radicals’ incessant and incomprehensible political campaigns. But armed clashes broke out in some areas; parts of the railway system was paralysed by factional struggles; and most worrying of all, at a time of military tension between China and Vietnam, the work of the army command was severely disrupted.90 Mao had hoped to use the campaign not only to humiliate Zhou but to reassert civilian leadership over the military, which was at last being persuaded to return to barracks and to let the Party run the country again. A subsidiary, and related, goal was to complete the elimination of real or supposed followers of Lin Biao. But Jiang Qing, as usual, pushed the envelope too far. On March 20 he wrote to her reproachfully:

For years I have advised you about various things, but you have ignored most of it. So what use is it for us to see each other? … I am 80 years old and seriously ill, but you show hardly any concern. You now enjoy many privileges, but after my death, what are you going to do? … Think about it.91

Mao's reference to his poor health was an uncharacteristic admission of his decline since Nixon's visit, two years earlier. He had lost more than two stone; his clothes hung off his thin shoulders and his whole body sagged. The least physical effort tired him. When he attended the Tenth Congress, oxygen tanks had to be installed in the car which took him on the three-minute drive to the Great Hall of the People; in his rooms there; and even at the podium in case he decided to speak (in the event, he did not). He drooled uncontrollably. His voice had become low and guttural, and his speech was almost incomprehensible even to those who knew him well.92

Kissinger remembered the struggle it cost him to emit each thought: ‘Words seemed to leave his bulk as if with great reluctance; they were ejected from his vocal cords in gusts, each of which seemed to require a new rallying of physical force until enough strength had been assembled to tear forth another round of pungent declarations.’93