“Yankees, keep it moving!”

On a sweltering-hot September afternoon in 1863, Union colonel Thomas Rose swatted away mosquitoes as he shuffled down the dusty Richmond, Virginia, street. He was one in a long, slow-moving line of captured Union soldiers. Dehydrated and exhausted, the soldiers struggled to keep upright as Confederate guards on horseback barked orders. Yet despite his parched throat and sore, bleeding feet, Rose managed to hold his head high and keep pace with his horse-riding enemy. He refused to let the Confederates, or “Rebels,” as he thought of them, see him suffer. Ahead of him in line, a younger officer stumbled and nearly collapsed.

If we don’t get some water soon, Rose thought, his black hair and beard dripping with sweat, we’re all gonna keel over . . .

Rose didn’t know where the Confederates were taking the seventy Union soldiers they’d captured. He and his fellow Northerners had come all the way from Chickamauga, Georgia, where they’d been taken prisoner by the Confederates and herded into overcrowded cattle cars. It had taken two days to reach Richmond by train, making stops along the way in South and North Carolina, where they were insulted and spat on by the local townsfolk. The men were given some water but no food, and there was no room to sit or lie down.

Now as Rose marched in the suffocating Virginia heat, his belly ached from hunger.

“Halt!” a Confederate yelled. The prisoners stopped in their tracks.

Rose raised his eyes to peer through a steamy haze of kicked-up dust. Ahead of him, an enormous three-story brick building loomed—Libby Prison.

It looks more like a warehouse than a prison, Rose thought.

Built on the outskirts of town, a few yards from the James River, the monstrous edifice with barred windows was to be his home for the foreseeable future. He realized that if it were this hot outside, inside wouldn’t be any cooler. Rose shuddered, knowing that once they entered the prison, some of his fellow soldiers—and even Rose himself—might never leave.

Thunderheads rumbled in the distance, the dark clouds rolling across the sky like advancing cavalry.

As Rose watched, two Confederate officers rode their horses over from the prison stables.

Surely that man riding in front isn’t in charge of the prison, Rose thought. He doesn’t look a day over twenty-five.

“Welcome home, boys,” the young man shouted in a thick southern accent from atop his horse. He was sharply dressed in a gray Confederate frock coat, its polished gold buttons almost blinding in the sun. A commanding officer’s hat shaded a narrow, clean-shaven face. To Rose, he almost seemed like a kid playing dress-up in his father’s clothes. “My name’s Major Thomas Turner. I’m the commander of this prison. My second-in-command is the old boy to my right, Warden Dick Turner—no relation.”

Rose glanced over at the commander’s underling. Unlike his boyish-looking superior officer, the older Warden Turner had a scarred face and a yellow, rotten-toothed grin. He held a bullwhip in his right hand.

“Y’all mind the rules, and we’ll get along fine,” Major Thomas Turner continued. “Step out of line, you’ll wish you were dead. See, ol’ Dick here used to run a plantation, so he knows how to run a tight ship.”

Around Rose, a few of the other prisoners shuffled uneasily. He knew they were thinking of the reports they had heard of the brutal conditions of Southern slave plantations, and the cruel nature of plantation overseers. Rose was a Northerner who believed that slavery must be abolished. Although many of his fellow Northerners were indifferent about the plights of enslaved people in the South, Rose was proud to lay his life on the line in honor of his belief. He wasn’t alone: if the newspapers were to be believed, more than two million Northerners of all backgrounds had joined the fight to end slavery and keep the country together. At the same time, about a million Confederates were fighting to hold on to their states’ legal rights to own human beings as property. They believed that if slavery ended, there would be no one to work the plantations and their economy would collapse.

BLACK AMERICANS IN THE CIVIL WAR

Americans of all backgrounds and ethnicities fought in the Civil War. Although exact numbers are unknown, at least 180,000 free black men fought for the Union Army. Some had formerly been enslaved, and some volunteered from as far away as Canada and the Caribbean. By the end of the war, 40,000 black soldiers had given their lives fighting for the right of all black people to be free.

Rose watched as Warden Dick Turner, in his gray Confederate uniform, kicked a prisoner who was muttering under his breath. The prisoner fell to the ground.

“No talking!” Warden Turner screamed.

While some others helped the prisoner back to his feet, Major Thomas Turner continued.

“There’ll be a head count every morning after reveille. Chow time is twice a day. My rules are simple: keep in line, do your time, and you live. Step out of line or try to escape—you die.” He paused and smiled. “Now y’all enjoy your stay.”

He nodded to one of the guards, who bellowed, “Inside, now!”

The prisoners began shuffling toward two massive wooden doors. Rose peered up at the towering building. Through the barred windows, he could see the ghostly shadows of the inmates moving around inside.

Once through the doors, a wave of damp heat and rancid air hit Rose like a punch in the face. The young officer who’d nearly collapsed during the march finally toppled over the moment he stepped foot in the building. He lay in a crumpled, convulsing heap on the wood-planked floor. Rose winced as the man began vomiting.

“Get that lazy Yank to his feet,” the guard barked.

Rose gritted his teeth and helped peel the young officer off the floor.

“Stick these boys on the second floor in the lower Chickamauga Room,” one of the guards told another, nodding toward a group of prisoners that included Rose. “And put the rest on the third floor. And somebody get this boy up—Lord almighty, what a mess . . .”

Rose followed the other prisoners up the creaking wooden staircase. Emerging on the second floor, he grimaced at the sight of the Libby inmates already there. Many were rail-thin and looked as if a strong breeze could knock them over. Yankee uniforms hung loosely from their skeletal frames. Their beards and hair were wild and unkempt but did little to hide drawn cheeks and sunken eyes. The air was stifling, the stink of a hundred or more unwashed men packed into one room almost unbearable.

How can a man last in this place? Rose thought.

He made his way into the room. There were no cots or blankets for cold nights. Here the prisoners had almost nothing, just a couple of crates and makeshift benches cobbled together from spare wood.

“Welcome to the Chickamauga Room,” one of the guards drawled. “Figured it’d be the most appropriate place to stick you fellers since that’s where y’all were captured.”

“I feel at home already,” Rose replied without missing a beat.

The guard laughed in return and left the new prisoners to find a bit of floor in the crowded room.

As Rose looked around, a crack of thunder shook the walls, followed by a collective groan in the room. Some of the men scrambled to their feet, seeming panicked, while the new arrivals looked on, confused.

Rain began to pour. As Rose watched the deluge outside the four small, barred windows, he realized he couldn’t ignore his scratchy, bone-dry throat a second longer.

“Pardon me, sir, where might I get some water?” he asked a prisoner standing next to him. The man was wearing a major’s uniform.

“In that washroom yonder,” the major said. He took his measure of Rose, then handed the colonel a metal cup.

Rose thanked him and headed over to the small room. There was a large sink and trough with a legion of flies buzzing around it. The colonel turned the faucet and filled the cup with brackish river water. He had barely wetted his gullet and stuck the cup back under the spigot for a refill when he heard a commotion coming from the first floor.

What’s going on down there? he thought, glancing at the stairwell.

Then he felt something crawling on his arm. Looking back, he saw a giant rat on his sleeve.

“AAH!”

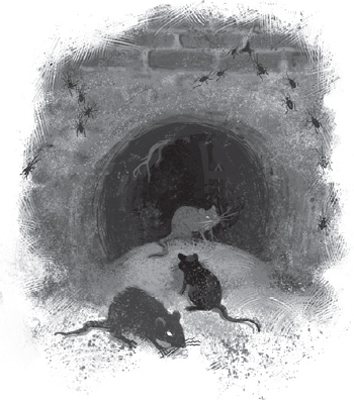

Rose ran out of the room, with the soaked, screeching rat clinging to his uniform. Before the creature could take a bite out of his neck, Rose reached up, grabbed hold of the squirming animal, and threw it to the ground. He watched in disgust as it scurried away. As he looked back into the washroom, to his horror he saw dozens of rats climbing out of the drain in the trough and through holes in the wall. They emerged from every opening—the windows, the stairwell, and each hole, crack, and cranny in the walls and floorboards.

One older, particularly crazed-looking prisoner with a white beard laughed.

“Say hello to the welcome wagon, fellas!” he cackled.

Rose watched in awe as the prisoners knocked the seemingly fearless rodents off their trouser legs in an almost comical dance.

Looking around, he spied the major who had given him the cup calmly observing the scene from his corner. Approaching him, Rose handed the cup back and asked, “What is going on here?”

The major grinned and shook his head. “I should’ve warned you about the rats. Happens every time it rains. They climb up through the walls to escape the flooding river water. Better get used to it, ’cause it rains quite a bit.”

Kicking what had to have been a three-pound rat off his boot, Rose turned to the window and stared out at the river and beyond. This is no prison, he thought. It’s the seventh circle of hell. And I’ll be damned if I’m going to rot in here!