The sewage turned out to be the breaking point for most of the men. Even Lieutenant Bennett, whose enthusiasm had been unwavering, seemed to be at the end of his rope.

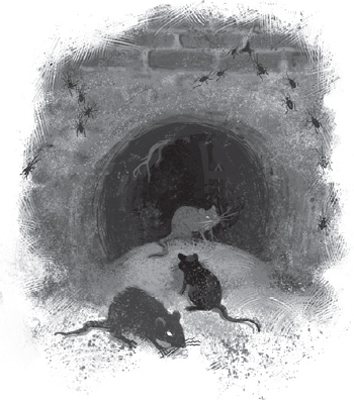

“I just can’t do it, sir,” he told Rose. “I can’t go back into those tunnels. I’m sore all over. I can’t take the air, the filth, the rats . . . I’m done.”

Hamilton looked at the shivering group of men who were once again huddled in a corner of the Chickamauga Room. They had been digging for weeks. Their tired eyes stared at the floor. Dried, cracked lips and sickly pale skin made them look more like upright corpses than living men.

Feeling deflated, the major was about to walk away when Rose spoke up.

“Gentlemen,” he said. “I know you’re tired. I know your bodies ache and your spirits seem broken. But we’re close. Hamilton and I have been checking the layout of the grounds from the windows, and have figured out a new angle. This next tunnel will be our way out. I give you my word. And if I’m wrong, then quit. No questions asked. Let’s all take tonight to rest, and then commence further discussion on the matter tomorrow.”

The men groaned in unison, then hesitantly agreed to Rose’s terms.

After the group separated, Hamilton turned to Rose.

“I don’t recall having any such discussion about a new tunnel,” he said.

Rose smiled. “I know. Perhaps we should have one now.”

Moving to a barred window, Rose pointed to a shed about fifty feet away from the east cellar. It stood between two larger buildings on the other side of a wooden fence that bordered Canal Street.

“I think we should try to tunnel into that shed,” he told Hamilton, his breath steaming in the cold January air.

Hamilton nodded thoughtfully. “It’s farther from the river, so the ground will be dry and won’t flood. It’s also distant from the rest of the prison, so we won’t have to worry about hitting any foundation posts.”

Later that day, at another meeting in the Chickamauga Room, the two men ran their plan by the others. It took a bit of convincing, but eventually everyone was on board with this final attempt to escape.

Digging on the new tunnel began that night. Although the men were still tired, once they’d managed to chisel through the wall, they found the soil easier to dig through this time around. It didn’t take long for them to get farther than they had with any of the other tunnels. This did a lot to lift their spirits.

February arrived. One afternoon, as Hamilton lay on the floor exhausted after a long night, he was approached by a young man named Robert Ford. Ford was an officer and one of Libby’s twenty black prisoners, who slept in the west cellar. Before getting captured, he’d been a teamster for the Union—a soldier who drove a team of horses (or oxen) to transport ammunition and other supplies for the war effort.

At Libby, Ford had been given a job as Turner’s hostler, the person who took care of the horses. Hamilton knew Ford was allowed to freely roam the grounds outside the prison walls during the day.

“Are you Major Hamilton?” Ford asked.

“You guessed right, friend.”

“Name’s Robert Ford.”

The two shook hands.

“How can I be of service to you?” Hamilton asked.

“It’s I who can help you,” Ford countered. “One of your associates approached me with the knowledge of your recent activities. I’d like to assist you in any way that I can.”

Hamilton felt he could trust Ford. There were rumors that Ford had helped previous escapees and that he knew a Union sympathizer in the area, a woman named Elizabeth Van Lew, who offered her home as a safe house for prisoners to hide. Some inmates said that Ford was in contact with Van Lew and that he had given previous escapees directions to her house.

“We’re attempting to tunnel into a shed on the other side of the fence, to the east,” Hamilton told Ford. “I think we’re close, but we don’t know exactly how far it is.”

“The tobacco shed.” Ford nodded. “It’s between the James River Towing Company and Kerr’s warehouse. I’ll see what I can do.” He lowered his voice to a whisper. “I know a benefactor who might be of service to prisoners once they’ve vacated this fine establishment. She has maps of safe routes going north.”

Hamilton’s eyes lit up. Maps with a list of safe houses—places where Union sympathizers hid escaped soldiers or people on the run from slavery—would be crucial to the men trying to make it back to the North.

He was about to ask Ford for more details when the doors flung open and Warden Dick Turner stormed in. The former plantation manager had six guards with him. He also had his whip in his hand.

Hamilton’s gut twisted. He knew this was trouble.

“All y’all line up for a head count,” he barked.

As the prisoners lined up, Turner looked right at Ford.

“Get back to work,” he growled.

Ford shot Hamilton a look, then retreated down the stairs.

Rose and Bennett walked over to where Hamilton stood.

“It’s a surprise head count,” Rose said. “Thank God we all decided to take the afternoon off!”

“Not true, major,” Bennett said. “Johnson and McDonald are in the cellar!”

“What?”

Bennett nodded, his eyes full of worry. “They said they weren’t tired, so I went to the kitchen with them about an hour ago. After they crawled down to the cellar, I pushed the stove back.”

This isn’t good, Rose thought, biting his lip.

“I said line up!” Turner screamed.

One of the guards began the head count. After he finished, he approached the warden.

“We’re missing two, boss.”

“Do it again, you idiot.”

Rose’s mind raced as the guard started counting a second time.

The count’s going to be short. We’re going to get caught.

Then he felt someone brush against him. He turned and saw Bennett slipping back in line after being counted. He soon noticed Hamilton doing the same thing.

Brilliant, Rose thought with relief. Now why didn’t I think of that?

The sickly prisoners did all seem to look alike, and their scruffy beards made it even harder to tell one from the other. Turner didn’t notice the ruse. This time the count came up to the right number. The escape plan was saved . . . this time.

THE STORY OF ELIZABETH VAN LEW

One of the most famous Richmond locals who helped Libby prisoners escape was Elizabeth Van Lew.

Van Lew’s father had a number of enslaved people in his household; the exact number is unknown. Growing up, Elizabeth Van Lew begged her father repeatedly to free them, but to no avail. Even after he died in 1843, his will had a stipulation forbidding his heirs to free the slaves. So, starting in 1860, Elizabeth paid them wages instead.

As tensions built between the North and South, Van Lew hoped Virginia would side with the Union. Of course, this didn’t happen. Worse still, her hometown, Richmond, became the capital of the Confederacy! Despite this, she knew she couldn’t stand by and do nothing. She got permission to bring food to Union prisoners held at Libby. To keep in good graces with the guards, she would bring them treats such as baked goods.

When the war broke out, Richmond’s citizens were shocked that Van Lew would dare help the enemy, but she didn’t care. She was in contact with a Union sympathizer on the prison staff, and when prisoners escaped, sometimes she would hide them in a secret room in her attic. After word got out to Union leaders that a local woman in Richmond was helping prisoners, the North officially made her a Union spy.

Van Lew would receive messages from Union sympathizers who worked in high offices of the Confederacy. She would smuggle these secret messages out of Richmond to where the Union army was stationed. Oftentimes these messages—which may have contained battle plans or supply shipment information—were hidden in a false-bottom plate warmer, and sometimes even in empty eggshells!

After the war ended, Van Lew was even less popular in Richmond than she had been before. She was also poor, having spent her entire inheritance purchasing the freedom of enslaved people in the area and helping the Union. At one point, she asked the United States government for money to live on. They said no, though President (and former Union general) Ulysses S. Grant did make her postmaster of Richmond during his term as president. Unfortunately, this job ended when Grant’s term was over. Van Lew spent her last years as a recluse, living off money sent to her from the grateful families of former Libby prisoners she’d helped. After she died in 1900, the family of one of these prisoners erected a granite headstone in her honor in Richmond’s Shockoe Hill Cemetery.