Robert Service on the porch of his Dawson City cabin, now a heritage site and tourist mecca. It was here that he wrote his first novel, The Trail of ’98.

Robert W. Service is a hard man to define. Perhaps the best-known English-language poet of the twentieth century, and certainly the richest, he refused to call himself anything more than a rhymester. A shy man and a dreamer, he played a dozen roles in his lifetime, often with costumes to match, while plunging into each masquerade—a cowboy in Canada, an apache in the Paris underworld—with the intensity of a professional. A self-described vagabond, he soaked up the background for his hugely successful novels and poems wherever his wanderlust took him—Tahiti, Hungary, Soviet Russia—difficult corners of the globe where, to his delight, he was unrecognizable.

Service has been a presence in my life since childhood. My mother knew him when she was a young kindergarten teacher in Dawson City; he even asked her to a dance—the kind of social affair he usually avoided. His original log cabin stood directly across from my childhood home under the hill overlooking the town. Early in my television career I spent three days with him in Monte Carlo—the last interview he ever gave. Three decades ago I published a short character sketch about him in My Country. Yet I cannot say I really understand him—a poet who refused to call himself a poet, a hard worker who claimed to be the world’s laziest man, a brilliant storyteller who invented himself in print.

I find it fascinating that he was able, thanks to his royalties, to purchase five thousand books for his library, yet scarcely any of them are books of poetry. “I’m not a poetry man,” he once remarked, “though I’ve written a lot of verse.” He made this clear in his autobiography, Ploughman of the Moon. “Verse, not poetry, is what I was after—something the man in the street would take notice of and the sweet old lady would paste in her album; something the schoolboy would spout and the fellow in the pub would quote. Yet I never wrote to please anyone but myself; it just happened that I belonged to simple folks whom I liked to please.” He amplified these remarks in—what else?—a poem, which he called “A Verseman’s Apology.”

The classics! Well, most of them bore me

The Moderns I don’t understand;

But I keep Burns, my kinsman, before me,

And Kipling, my friend, is at hand.

They taught me my trade as I know it,

Yet though at their feet I have sat,

For God-sake don’t call me a poet,

For I’ve never been guilty of that.

By his own admission, the “Canadian Kipling,” as he was universally dubbed, suffered all his life from an inferiority complex that made him keep his distance from many fellow writers of whom he stood in awe. In his comfortable years, when he retired to the Riviera, his neighbours included such luminaries as Somerset Maugham, Bernard Shaw, and Maxine Elliott. “Oh my, I’d be scared to meet Shaw,” Service remarked to a friend. “Somerset Maugham was a neighbour of mine but I’m scared of these big fellows. I like eating in pubs and wearing old clothes. I love low life. I sit with all the riff raff in cafes and play the accordion for them.”

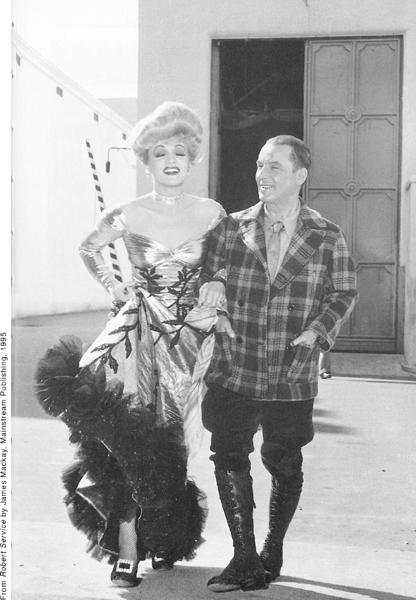

Strangers encountering Service at the height of his fame were astonished to discover that he was not the rough, profane roustabout they had envisaged from his poetry. How could they identify this quiet, almost inconspicuous gentleman as the author of “The Shooting of Dan McGrew”? In Hollywood, the casting department of The Spoilers, in which the poet played himself, objected that he was “not the Service type.” In Toronto, a reporter schooled in Service’s best-selling ballads wrote that “his face is mild to the point of disbelief.” Service agreed. “My face is much too mild,” he said, “for one who has been a hobo, ‘sourdough poet,’ war correspondent, and soldier.” He might have added ranch hand, ditch digger, and dishwasher in a brothel.

My mother, who arrived in Dawson in 1908, made a point of hurrying down to the Bank of Commerce as soon as Service was transferred there as a teller. She and a friend had thought of him “as a rip-roaring roisterer,” she remembered, “but instead we found a shy and nondescript man in his mid-thirties, with a fresh complexion, clear blue eyes, and a boyish figure that made him look younger. He had a soft, well-modulated voice and spoke with a slight drawl.”

Service in Hollywood with Marlene Dietrich on the set of The Spoilers, made up to look young. The casting department said he wasn’t “the Service type.”

Robert Service could never escape the Yukon, no matter how much he tried. Of all the verses he wrote—and the number exceeded two thousand—the one he really loathed was the first one he published, which brought him the fortune he craved and the fame he despised. “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” owed as much to the American Wild West as it did to the Canadian North. Service in fact hadn’t even reached the Klondike when the famous ballad first made its appearance in Songs of a Sourdough.

Now, almost a century later, it has become the best-known folk ballad of our time, shouted, whispered, roared out, and recited by half-inebriated monologists (including me) at a thousand parties and from a hundred stages—satirized, rewritten, set to music, parodied, praised, sneered at, and condemned. It is an abiding irony that so much of Service’s work that excited interest at the time of publication has been forgotten, but “Dan McGrew” and its companion ballad “The Cremation of Sam McGee” have survived.

For the fifty years following his arrival in the Yukon, Service continued to churn out verse, much of it highly popular—his Rhymes of a Red Cross Man was on the New York Times best-seller list for almost two years—but it irked him that the first work he wrote at that time turned out to be the most enduring. “I loathe it,” he told me toward the end of his life. “I was sick of it the moment I finished writing it.” But for all of his long career he was asked to recite it, time and time again, and he did, almost to his dying day.

What might be called the Dan McGrew Industry began a decade or so after the ballad appeared in print. “Is there a Doughboy who has not heard ‘The Shooting of Dan McGrew’?” Louis Untermeyer asked in The Bookman in 1922. Among the tens of thousands who committed it to memory were the Queen Mother, the Duke of Edinburgh, and former president Ronald Reagan. Bobby Clarke, the Broadway comedian, parodied it on the stage in Star and Garter. Miss Marple, Agatha Christie’s fictional detective, quoted from it in one of the TV episodes that carried her name. Billy Bartlett, the British music-hall satirist, made a recording of it. So did Guy Lombardo, the bandleader. Tex Avery, the animation genius, spoofed it twice, in 1929 as Dangerous Dan McFoo and again in 1945 as Dangerous Dan McGoo, the title character being a cartoon dog. Hollywood turned the ballad into two silent films. The first, in 1915, was marred by a happy ending; the second, in 1924, starred Barbara Lamarr and Mae Busch, then the reigning queens of the silver screen.

Hollywood made two movies based on “The Shooting of Dan McGrew.” The first, shot in 1915, had a happy ending. The second (above) was faithful to the original.

“Dan McGrew” has been parodied again and again, often obscenely (“And there on the floor on top of a whore lay Vancouver Dan McGrew”). There is at least one gay version (“And there on the floor with his arse-hole tore …”) that made the rounds of the mining camps in the Depression days and later. There is a hip version by Turk Murphy’s Jazz Band. More recently, a new company, Pied Piper Productions, has been promoting its own version of the ballad with hand-carved puppets. The Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s version, with music by Hair’s Galt McDermott, is still in the repertoire, the first-ever production of a ballet with a Canadian theme, while a recent novel by Robert Kroetsch, The Man from the Creeks, takes as its title a familiar line from the ballad.

Service was that curious mixture, a public figure who was always an intensely private man. When an article in The Times of London listed his name among the poets who had been killed in the Great War, he made no effort to correct it (the confusion arose because one of his brothers was killed at the Somme). “It rather pleased me that my efforts of self-obliteration had succeeded,” he recalled. He was living in Nice at the time, where few of his neighbours knew who he was. “I enjoyed the irresponsibility of living in a foreign land where one is an onlooker, and cares nothing for the way things are run as long as one’s comfort is assured.”

His biographer James Mackay has called the poet’s autobiography, Ploughman of the Moon, “a masterpiece of obfuscation.” It contains not a single date and no proper names except those of his four elderly aunts. He does not tell us when or where he was born and raised, or who his spouse was; he simply refers to her as “the wife.” The rest of the names in the book are entirely fictional. He refers scarcely at all to his mother and does not name any of his nine siblings. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, Ploughman is a highly readable book, full of anecdotes, many of them exaggerated since Service was never one to let the truth get in the way of a good story. His second volume of memoirs, Harper of Heaven, is equally murky.

As a result, his biographers have been faced with the maddening task of trying to figure out who was who and where was where from Service’s vague accounts of his career. The first two—Carl Klinck, 1976, and G. Wallace Lockhart, 1991—did their best but in the end gave up or got it wrong. One can only applaud the investigative work of Mackay, who managed to untangle the more baffling aspects of Service’s literary career.

In spite of his soft accent, he was not born in Scotland, as so many of his fans have assumed, but in Lancashire, in January 1874. Four years later the family moved to Glasgow, but two of the Service boys, Robert and his younger brother, John, were off-loaded to live with their uncle, the postmaster of Kilwinning, an Ayrshire market town some twenty-four miles southwest of Glasgow. Apparently the burden of handling five boys and five girls was too much for Emily Service. In his autobiography Service makes no mention of John or indeed of any of his siblings. As a small boy he kept to himself and recorded in Ploughman hearing his grandfather remark, “Yon’s a queer, wee callant. He’s sooner play by himsel’ than wi’ the other lads.” That was true, Service wrote. “Rather than join the boys in the street I would amuse myself alone in the garden, inventing imagination games. I would be a hunter in the jungle of the raspberry canes; I would be an explorer in the dark forest of the shrubbery; I would squat by my lonely campfire on the prairie, a little grass plot where the family washing was spread. I was absorbed in my games, speaking to myself or addressing imaginary companions.” He looked forward, he remembered, to bedtime where he had “the most enchanting visions” of “shining processions of knights and fair ladies.”

Here were the early clues to that wanderlust that would set Service off, always on his own, on voyages of exploration to distant climes, a solitary witness soaking up local colour or living vicariously through the lives of strange and, to him, exotic people. They also provide an insight into the role-playing that marked his adult life and his habit of choosing whatever costume he believed would allow him to merge with the background in those communities he sought out. When his royalty cheques raised him to the level of the wealthiest poet in Paris, he was not above depicting himself as a penniless scrivener in worn clothes, scarcely able to make ends meet. In that case his Scottish parsimony helped create the illusion.

“A ravenous reader” as a child, he gobbled up the works of every adventure writer from Captain Marryat to Jules Verne, not to mention Burns and Kipling, the only poets with whom he felt comfortable. There was more than a hint of the future rhymester when on his sixth birthday at a family feast he asked his grandfather if he might be allowed to say grace. Without waiting for an answer, he bowed his head and began:

God bless the cakes and bless the jam;

Bless the cheese and the cold boiled ham;

Bless the scones Aunt Jeannie makes

And save us all from bellyaches. Amen

In Ploughman, Service noted that this first poetic flutter “suggests tendencies in flights to come. First it had to do with the table, and much of my work has been inspired by food and drink. Second, it was concrete in character and I have always distrusted the abstract. Third, it had a tendency to be coarse, as witness the use of the word ‘belly’ when I might just as well have said ‘stomach.’ But I have always favoured an Anglo-Saxon word to a Latin one, and in my earthiness I have followed my kinsman, Burns. So, you see in that first bit of doggerel there were foreshadowed defects of my later verses.”

Young Service did not see his father, a failed banker, for four years until the family was reunited in Glasgow, thanks to a legacy received by his mother. The balding figure with the mutton chop whiskers and “the reddest face I ever saw” failed to make an impression. “I cannot reproach him for his failings,” Service was to write in a revealing passage, “for they were my own—laziness, day dreaming, a hatred of authority, and a quick temper.… I hated to work for others and freedom meant more to me than all else. I, too, was of the race of men who don’t fit in.”

Service was not popular at school. “I was too much of a lone dog and I disliked games.” But these were some of his happiest youthful years. He wrote some poetry for small publications, dabbled in amateur theatrics, and for a time he had his future set on becoming a professional elocutionist, practising his craft, complete with gestures, in front of a mirror as so many of his avid readers would do when his own ballads appeared.

He left school in 1888 at the age of fourteen and took a job as apprentice in the local branch of the Commercial Bank of Scotland. “It was obvious,” he remembered, “that I had no vocation for banking,” but it suited what he always insisted was his “prejudice against hard work.” It was an easy job and “I tried to make it still easier. I dawdled over my daily errands and dreamed over my ledger. I made rhymes as I cast up columns of figures.” Was he really such a good-for-nothing as he makes out? James Mackay, examining such records as exist, suggests that he was well thought of by his superiors and was “a diligent, if unspectacular employee.” Service’s description of his banking career, such as it was, is another example of his lifelong practice of using self-deprecation to enhance his personal narrative.

It is this that makes him such a contradictory figure. Was he the solitary dreamer who drifts through his autobiographies? The lazy layabout doing his best to avoid hard work or, indeed, work of any kind? There is more than one suggestion that this was a pose to cover up what he constantly referred to as his inferiority complex or to assuage the guilt that nagged at him because he didn’t think of himself as a real poet.

Service portrayed himself as a lonely wanderer, and that rings true. He thought nothing of deserting his family for weeks, even months, to travel to unlikely corners of the globe. The Yukon made him famous, but when he had the opportunity to return to his old Klondike haunts after the Second World War, he bowed out, sending his wife and daughter in his place. There is no evidence that he ever had a close or intimate friendship with anybody—no one to whom he could pour out his heart or relive old times. There are some hints of a schoolboy love in Glasgow and an affair, later, in Kamloops, B.C., but only hints. When Service came to write his memoirs he avoided such personal touches. He married, he tells us casually, because he needed a wife; fortunately he selected one who indulged his solitary inclinations. His parents and his siblings are all distant figures in his life; he barely recognized those he encountered in his later years. Who, then, was the real Robert Service? Who was that masked man? He was, I suggest, whomever you wanted him to be or what, at any moment, he decided to be. As a poet, his credo was to give the public what it wanted; as a human being, all he asked was to be left alone.

The book that changed Service’s life was Morley Roberts’s The Western Avernus: Toil and Travel in Further North America. Roberts, who had worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway in the construction period, seduced Service with his portrait of western Canada in the early 1880s. Service went to the Canadian immigration office and stocked up on pamphlets about the prairies—pamphlets that marked the beginning of the Liberal Party’s immigration propaganda, which brought a million newcomers to the West. “Cattle ranching; that was the romantic side of farming, and it was romance that was luring me.” Service’s instinct told him that in quitting his bank job after seven years and making a clean break from the Old World he was doing the right thing. “I knew a joy that bordered on ecstasy as I thought: ‘I too, will be a cowboy.’ ”

That was the first of his many roles. He bought a big knife with a spring blade, which he called a scalping knife, and also an air rifle so he could practise for hours being quick on the draw. His ambitions knew no horizons: “Henceforth I would be a fellow of brawn and thew. I would work in mines and sawmills, in lumber camps and railway gangs, on ships and ranches. I would run the gamut of toil. But before all I would be a cowboy.”

He needed a costume—he would always need a costume—and he settled on a discarded Buffalo Bill outfit that his father had bought second-hand at an auction, together with a pair of high-heeled boots, a set of chaps, and a Mexican sombrero. He booked a steerage passage on a tramp steamer headed for Halifax, and there at the dockside, as his friends were bidding him farewell, his father appeared and handed him a small package. Service, who shunned displays of emotion, hurried aboard ship before opening his parting gift. It was a small Bible. He never bothered to read it but he kept it all his years, “the one possession that no one ever tried to steal.”

He never saw his father again, although the old man wrote to him many times. In his final letter he begged his son to pay him one last visit. “Even if you cannot come just write and say you will.” But Service never answered, and when his father died of a stroke, “I must confess I felt a sense of relief.” The poet did not have much family feeling, then or later. He showed little curiosity about his ancestors, his immediate forebears, or his siblings, some of whom would give him up for dead in the years to come.

No sooner had he reached Canada than Service unpacked his Buffalo Bill costume and wore it constantly. The train that took him across Canada was crammed with immigrants like himself, all attired in such a variety of outlandish outfits that his own caused little comment. He had come to the new world to be a cowboy, but when he reached the end of his journey near Cowichan on Vancouver Island, his first jobs were disappointingly mundane—picking up acres of stones for a future farm and weeding endless rows of turnips.

It was monotonous, back-breaking work. Service endured it because he found the surrounding scenery so magnificent. He revelled in “the blue purity of the sky, the mountains that rose to meet it, the unexplored bush that came right down to the clearing … a dream world worthy of a dreamer.” Later he moved north to a farm near Duncan, a three-mile tramp through the woods. He lived in a shack, the most remote in the Cowichan Valley, where his chores were minimal and his isolation gratifying. Primed by a newly discovered hate for hard labour, he “energetically cultivated laziness,” or so he says in his self-belittling memoir.

That fall of 1896 he moved again, milking a herd of Holsteins for a dairy farm; but in November, when the frost-caked mud was knee-deep in the yard, he decided to head south toward California. “I was pleased to see how I had risen to the occasion. I could earn my bread by the sweat of my brow.… I was not a little proud, and ready for the next phase in the adventure of living.”

For the next year Service drifted about the American southwest, living like a hobo, taking odd jobs, and dreaming away the weeks and months without any firm plan. Within a month in Seattle his grubstake of one hundred dollars had dwindled to half. Thanks to a rate war he got himself a narrow steerage bunk for a dollar on the SS Mariposa bound for San Francisco. Service found himself jammed into the hold with a dozen others; “the air was so thick you felt you could slice it like Camembert.” Everybody aboard that wallowing craft was deathly ill, including Service, who was so exhausted that when the man on the bunk above him vomited on his upturned face, he did not have the energy to turn his head away. It was not an auspicious introduction to the sunny south.

In San Francisco he found a room at the base of Telegraph Hill for fifty cents a day. He haunted the sleazier dives of Chinatown where he could buy a beer and watch a stage show for ten cents. After a month and close to destitution, he was overcome with a “first feeling of fear.” The misery he saw, the derelicts and down-and-outers with whom he rubbed shoulders filled him with disgust. “Frankly, I was scared.”

He answered an ad on a blackboard offering two dollars a day for labourers. He took it without knowing what it entailed and found himself shipped by train to a contractor who put him into a gang driving a half-mile tunnel through the wall of San Gabriel Canyon to the Sacramento Valley. In the dank and murky bowels of the earth he toiled ten hours a day until, happily, he was transferred to another dawn-to-dusk job shovelling gravel. When at last he quit he was given a pay-cheque for twenty dollars, which he found he could not cash. He discounted it to a stage driver for half its value and slept that night in a chicken house.

In Los Angeles he secured a room for a dollar a week and managed to keep alive on fifteen cents a day. On First Street, he found he could get a five-course meal for ten cents. The portions were small but included four grey slices of bread. Service would select a spot opposite a customer who was just finishing his meal, and if there was any bread left he would ask for it. Each evening he would hang around the fruit market looking for an apple or orange that had fallen into the gutter. After seven, the agnostic poet would head for the Pacific Coast Gospel Saloon, where, to obtain a piece of dry bread and coffee, he would join in prayers for an hour. “The bread was cut in fair-sized chunks,” he remembered, “and some of us grabbed two. I was a ‘twofer.’ ” Later he offered to wash the coffee cups and was given an extra piece of bread for the task.

Surprisingly, in spite of such vicissitudes, these were days of serenity for Service. “I knew now that brute toil was not for such as I,” he wrote. “Was I not free and without responsibilities? No duties, no grinding toil, no authority over me.” Occasionally, in an introspective moment, he would ask himself if he was fitted for anything. “I had moments in which I saw disaster in front of me; but for the most part I was buoyant and enchanted with my surroundings.… If I was heading for disaster, I was doing it very cheerfully.”

In the public library, “that sanctuary of books,” he felt at peace with all mankind. San Francisco had made him want to write stories, “but this city made me want to make poetry … newspaper poetry, the kind that simple folks clip out and paste in scrap books.” He sent some samples to a local paper, which promptly published them. One, called “The Hobo’s Lullaby,” carried the line: “My belly’s got a bulge with Christmas cheer”—“typical,” Service remembered “of my tendency to the coarse and the concrete.” In this way, he discovered that he “would rather win the approval of a barman than the praise of a professor.”

The library provided food for the soul, but in his straitened circumstances not enough for the body. He thought constantly of food and was often light-headed because of the lack of it. He would lurk for hours before restaurant doors just to imbibe the smells of cooking, and then he would return to his room to munch on stale bread and imagine it was roast beef. Once, “I actually found myself scraping with my teeth on a banana skin a man threw on the sidewalk. He turned and caught me at it, but I pretended I had picked it up to prevent someone slipping on it. He looked hard at me and tendered me a dime, which I proudly refused.”

He could not bring himself to write home for help: “I would have died rather than confess my humiliating plight.” At the age of twenty-four he saw nothing but hard work and poverty in his future. There were times when he suffered a sense of panic as the prospect of starvation stared him in the face. When an acquaintance told him the season for orange picking was just beginning, he went to work for a Mexican contractor scrubbing the fruit clean in a tub and later—a promotion!—actually picking it from the trees. For Service that was heaven itself. “As I plucked the golden fruit, often I paused to look around with something like rapture. About me, the grove billowed like a green sea, while above me was a blue sky of perfect serenity. I was so happy up there in my leafy world, I hated to descend.” He sang gaily as he worked. This was a job for a poet! “How I wished it would last forever.” But, of course, it didn’t. As a last resort, Service decided to take out a classified ad in a local paper:

Stone-broke in a strange city. Young man, University non-graduate, desires employment of any kind. Understands Latin, and Greek. Speaks French, German, and Chinook. Knowledge of book-keeping and shorthand; also of Art and Literature. Accept any job, but secretarial work preferred.

To this published plea he received but one reply, from a shabby man in a shabby room in a suspiciously shabby building. His job, he was told, would be to tutor three young girls in San Diego “who want to learn how to talk about books and art stuff.” Service took the job, bargained the agent down to a two-dollar fee, and bought a train ticket for another six, leaving himself with three dollars. He proceeded, as directed, to a San Diego suburb. There he located the remote Villa Lilla, with a cupola from which dangled a red lantern. He was greeted by a Madame Ambrose, “a capacious lady draped in a Spanish shawl,” who told him he was the seventh sucker the commission agent had sent down on an errand. “He’ll get hisself into trouble one of these days,” she said, darkly.

The villa was, of course, a high-class bordello, a truth that slowly dawned on the naive poet only after several days. The Madame and her three “daughters” liked him, especially when he sang and accompanied himself on a guitar that they lent him. Madame Ambrose gave him a job as a handyman, and in return Service showed them respect and “a humble desire to please.”

He was shy and diffident, for it was some time since he had spoken to a woman. When he finally made his farewells they all insisted on kissing him on both cheeks, to his embarrassment, and presenting him with the guitar. As he walked off down the path they waved to him cheerfully from the porch. “In that Mission setting,” he remarked, “they might have been a Mother Superior and three Sisters.”

Service now decided to walk to Mexico “because it would be a pity not to visit that romantic land.” He travelled gypsy-fashion, sleeping on the mesa or on a beach, for he “had the arrogance of wide spaces and the disdain for folks who sleep in beds.” In ten days of wandering he found he had only spent a dollar. “I was in rare walking fettle and could reel off my thirty miles between dawn and dusk.” Only one thing bothered him: he could not afford to buy a new pair of shoes and did his best to save leather by taking them off and trudging along the highway barefoot.

He slept one night in a dry ditch on the outskirts of Santa Ana. The following day he suddenly felt forlorn. He hadn’t shaved for days, his trousers and jumper were stained and torn, and people were staring at him “as they would at a half-crazy man.” Even the guitar failed to bring him solace. “When one is gloomy one does not make gay music.” He returned to Los Angeles early one morning “like a whipped dog,” rented a small cubicle in a Salvation Army hostel, “the headquarters of the hobo fraternity,” and the next day sat in a public square trying to figure out his future. He managed to get a job burrowing into a hill to make a tramway tunnel until two of his fellow workers were injured. He quit, went back to the derelicts in the square, and wrote some verses called “The Wage Slave,” which he says he never submitted to any newspaper. However, years later he saw them included in an anthology by Upton Sinclair.

He took a job as a dishwasher but was no good at that. Back on a park bench, he saw a newspaper with a headline about a ton of gold arriving from the frozen North. “It did not interest me a bit. The Klondike? Bah! Let others seek their fortune in that icy land. Give me the sunshine and the South.” He would hit the gypsy trail again: Colorado, Nevada, Arizona, Texas, “magic names that appealed to the imagination.” While others struggled up the frozen passes, Service sauntered idly through the American southwest.

“Among my cherished souvenirs,” he wrote many years later, “is a worn dime. I think I must have tendered it a hundred times with a hollow smile, saying: ‘Excuse me, Ma’am, but I’m so hungry I’m willing to give my last ten cents for a bit of dry bread and a glass of water. I’m not a bum, ma’am. Please let me pay.’ ” They never did, but in the majority of cases Service got a free meal.

As the result of a narrow escape from a locomotive while crossing a wooden trestle, Service lost his zest for wandering. He returned to Los Angeles, briefly toyed with the idea of joining Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War, but instead decided to return to the Cowichan Valley. His days there as a cowboy came to an end when a big Holstein bull knocked him over, cracking two ribs. Fate then intervened when the local storekeeper departed and Service replaced him, exchanging the bunkhouse for a bedroom.

“I have had great moments in my life,” Service was to write, “when it seemed the gates of Heaven opened wide and I stepped through them from the depths of hell.” Now, suddenly, he was transformed into a middle-class storekeeper with a starched collar and a blue serge suit, a welcome guest at his employer’s dinner table.

His euphoria did not last and his job began to pall. “I hated the buying and selling, and I loathed the arid forms of the Post Office.” He began to imagine himself as a pedagogue. “I saw myself in a frock coat with a gold Albert across a rounded waistcoat.” Why not? He would go to college and become a Master of Arts. No sooner had he reached that decision than he stopped reading novels and concentrated on textbooks. But it was hard to keep his mind on his studies. “Often I wanted to throw the hated things out of the window and write mad sonnets to the moon.” Algebra had defeated him.

When he was writing Ploughman of the Moon, Service was always conscious of the title; the work is studded with references to the moon and moonlight. Now, he says, at this point in his career, the moon came to his aid: “Its serene light seemed to solace me. It said, ‘Don’t worry. All will come out right, but you’re on the wrong track. It’s writing you should be, not bothering your brain with bloodless abstractions.’ ” According to Service, “the moon whispered a poem in my ear.” He sent it to Munsey’s Magazine. Two months later it was printed and he received a cheque for five dollars. He had already quit his job in Cowichan and moved into a friend’s shack to cram for his exams. Having saved two hundred dollars, he thought he had enough to carry him through his college term. There were problems: he passed his exams in Victoria with high marks except for algebra and French. That meant supplementary exams; to keep up with his well-dressed and younger classmates he would need a new suit and accessories. The clothes cost one hundred dollars and by the time he paid for his textbooks, he was down to sixty. It just wasn’t enough. “I was indeed a failure. I had tried to storm the citadel of decent society, and been thrown into the ditch.… To what shabby fate was I drifting?”

What else could he do? During his long nocturnal walks he tried to figure out a future for himself. Ragtime kid in a honky-tonk? Parisian apache? Rose gardener? Herring fisherman? He was at the end of his tether. “Where now was that guardian angel who always interposed to save me in my extremities?”

No angel appeared. But on Service’s wall there reposed a dog-eared scrap of paper that, magically, would be the means by which he changed his life. It was a testimonial that he had obtained from his Scottish bank manager seven years before. It was this that got him a job with the Canadian Bank of Commerce, even though he was older than most applicants. The bank took him on trial for fifty dollars a month. To Service that figure was so astonishing that he actually tried to bargain the bank down to half the amount. “I’m Scotch,” he told the inspector. “I could get along on that.” He was finally persuaded to accept the offer and went to work in the winter of 1903–4 at the Victoria branch at the corner of Government and Fort streets.

This marked a major turning point in Service’s peripatetic career. Now he could afford to rent a piano and a ready-made dinner jacket. In July 1904, he was transferred to the bank’s branch in Kamloops where he immediately bought a pony and tried to take up polo. He hated the game but loved the costume and had himself photographed in it to send to his family. He bought himself a banjo and strummed away at it happily during his leisure hours.

At this time literature ceased to exist for Service. He scarcely bothered to read a book. “My sense of poetry, so strong in my poverty and my desert wanderings, now seemed to have deserted me. My whole ambition was to get on in the bank, and I was prepared to give it my lifelong loyalty. I knew I was not suited for the job, yet I had no hope in any other direction, and I was intensely grateful for the safety and social standing it offered.”

He was well settled when the bank told him they were transferring him to the Yukon and presented him with a two-hundred-dollar cheque to buy a coonskin coat. He bought the coat for one hundred dollars, pocketed the profit, and left for the North where, unlike the stampeders of 1898, he had no intention of making his fortune. But he did so in a manner putting the Kings of Eldorado to shame.

Service was given his first introduction to the Yukon from a passenger coach on the White Pass and Yukon Railway during its one-day transit through the Coastal Mountains from Skagway to Whitehorse. Weaving along beside the track was a worn pathway still bearing the visible marks of thousands of boots—the famous Trail of ’98. Bursting from a dark tunnel and onto a dizzy trestle, the train passed over the notorious Dead Horse Gulch where three thousand pack animals had perished during the great stampede. On the far side of the summit, the train rattled past the green headwater lakes—sinuous glacial fingers that led to the Yukon River. After that came the gloomy gorge of Miles Canyon and the frothing waters of the Whitehorse Rapids. At the end of the line Service could see a huddle of frame buildings, log cabins, and wooden sidewalks, nestling beneath the low hills on the banks of the mighty Yukon.

This was Whitehorse, the gateway to the North, but hardly the rough-and-tumble community of legend. Here Service would find himself passing the plate in the Anglican Church. “Though I may not believe in religion,” he was to write, “I believe in churches. They give me a sense of social stability.”

When the hectic summer came to an end and the tourists as well as prospectors and traders had departed, the bank’s business dropped off. Those who were left behind made their own fun, and the winter season was marked by a round of dances, concerts, at-homes, receptions, and other community events. In those days, long before radio and television, when the movies were silent, the art of elocution flourished.

When Service recalled those days, he remarked with his usual diffidence, “My only claim to social consideration at this time was as an entertainer, and a pretty punk one at that. I could sing a song and vamp an accompaniment, but mainly I was a prize specimen of that ingenuous ass, the amateur reciter.” His repertoire included those old standbys “Casey at the Bat,” “Gunga Din,” and “The Face on the Bar Room Floor.” These soon became stale from repetition, and Service was at a loss until the town’s leading journalist, Stroller White, suggested he recite something of his own. After all, he recalled, Service had once submitted a poem to the Whitehorse Star during his days in Victoria.

The suggestion intrigued the would-be rhymester. He knew he wanted a dramatic ballad suitable for recitation. But what? He needed a theme. What about revenge, he asked himself. “Then you have to have a story to embody your theme. What about the old triangle—the faithless wife, the betrayed husband?.… Give it a setting in a Yukon saloon and make the two guys shoot it out.”

But that was too banal. Service realized he needed a new twist to an outworn theme. It struck him then to “tell the story by musical suggestion.” It was a brilliant concept and one that would help transform the one-time hobo into a wealthy celebrity.

On a Saturday night, returning from one of his many nocturnal walks, he passed an open bar. The sound of revelry gave him his opening line: “A bunch of the boys were whooping it up …” Excited by this idea, and not wanting to disturb Leonard De Gex, the bank manager, and his wife, he crept down the stairs from his room above the bank, entered the teller’s cage, and started to complete the ballad. Unfortunately, Service wrote in Ploughman of the Moon, he had not reckoned with the ledger keeper stationed in the guardroom, who, on hearing a noise near the safe, thought it was being burgled. He levelled his revolver and “closing his eyes pointed it at the skulking shade.” Luckily, Service wrote, “he was a poor shot or ‘The Shooting of Dan McGrew’ might never have been written.”

The story is pure hokum. When, in 1958, I challenged him on it, Service cheerfully admitted to making it up. “I’d like to say he fired a shot at me,” he said. “And I’d say it too but there are men still living who were there and I can’t get away with it, you see.” But of course he did get away with it. The story of the scene in the teller’s cage went unchallenged for years.

Service finished his ballad but could not recite it at the church social; it was too raw and, its author remarked to me, it contained “too many cuss words.” Then, one evening, he encountered a big mining man from Dawson, portly and important, who removed his cigar long enough to remark, “I’ll tell you a story Jack London never got,” and spun a yarn about a man who cremated his pal. A light bulb flashed in Service’s mind: “I had a feeling that here was a decisive moment of destiny.” He left and went for a long, solitary walk. On that moonlit evening, his mind “seething with excitement and a strange ecstasy,” the opening lines of “The Cremation of Sam McGee” burst upon him, and soon “verse after verse developed with scarce a check.” After six hours, the entire ballad was in his head, and on the following day “with scarcely any effort of memory” he put the words down on paper.

It makes an appealing and romantic story, this sudden inspiration on “one of those nights of brilliant moonlight that almost goad me to madness” and it certainly jibes with the title of his memoirs. Service liked to suggest that it was all play and no work for him, that he never needed to correct his first drafts, but the facts, certainly in the case of “Sam McGee,” are at variance. Here is the first stanza that Service claimed poured out of him intact on that moonlit evening:

There are strange things done in the Midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

Grubbing through the Yukon Archives, James Mackay came upon the original draft of the ballad, which shows how carefully Service would polish and refine his work:

There are strange things done after half past one

By the men who search for gold;

The arctic histories have their eerie mysteries

That would make your feet go cold

The Aurora Borealis has seen where Montreal is

But the queerest it ever did spot

Was the night on the periphery of Lake McKiflery

I cremated Sam McKlot.

In this early version of the ballad, we can see Service struggling to develop the galloping rhythm that gave his work such an appeal to platform performers. Here he introduced the inner rhyming that is not present in “McGrew” but marks so many of his later ballads. Each of his lines is seven beats long, divided into two sections; the first four beats contain the inner rhyme: “The Arctic trails have their secret tales” while the next three beats repeat, amplify, or expand the original statement, “that would make your blood run cold.”

Service’s audiences were used to this pattern through the nursery rhymes of childhood (“Jack and Jill,” “Old King Cole,” for example) and school-book standbys such as “The Wreck of the Hesperus.” Service himself was brought up with this metre, and in his ballads he rarely departed from it. But it must have galled him in later years to realize that these twin efforts, which he tossed aside in a drawer with his shirts, should be the ones that would enshrine his reputation. He wrote some two thousand verses and published at least a thousand, but these two ballads, along with “The Spell of the Yukon”—a phrase he put into the language—are the only ones that are still remembered, and all from that first collection. Of the three, the one he loathed, “The Shooting of Dan McGrew,” is still the most often quoted.

The two ballads are quite different. “McGrew” preserves the theatrical unities; it takes place on a single set, the Malamute Saloon, and in “real” time: the entire action occupies not much more than ten minutes. “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” by contrast, is acted out like a wide-screen movie. It moves through time and space along the Dawson Trail to Lake Laberge, and it depends entirely on its Yukon environment (“And the heavens scowled and the huskies howled and the wind began to blow”). “McGrew,” by contrast, is that old standby, the Western shoot-’em-up, or it seems to be.

Service’s personal lexicon was crowded with short, blunt words that fitted his subjects. In “McGee,” for instance, there is scarcely a word longer than two syllables, and the exception “cre-ma-tor-ium” is spelled out thus for bizarre and comic effect. Service changed “search for gold” to “moil for gold” and made that unexpected verb his own. It is so intrinsically connected to the ballad that I doubt any writer would dare use it for fear of being called a copycat. (Curiously, one Service scholar, Edward Hirsch, managed to get it wrong when he quoted the line as “men who toil for gold.”) Occasionally, when Service couldn’t find an offbeat word to suit his purpose, he made one up. Thus, in “McGrew,” the stranger’s eyes “went rubbering round the room.” It’s not in the Oxford dictionary as a verb, but it certainly fits.

The author of “McGee” was not above adding a bizarre and mystic note to his work—as when he flings the frozen corpse into the roaring furnace of a derelict steamboat, the Alice May, which lies rotting on Lake Laberge (or Lebarge, as he spells it), to pin down the rhyme. There was indeed a derelict steamer, Olive May, rotting away at the southern tip of the lake not far from Whitehorse, which Service would have encountered on one of his lonely walks. As a youth he had been fascinated and horrified by the stories of martyrs burned at the stake in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, and that surely was in his mind when he revised the ballad, with McGee thawing out gratefully “in the heart of the furnace roar” and providing Service with a tag line that always brought a laugh from his audience: “it’s the first time I’ve been warm!”

Some critics believe that “McGee” is the better of the two ballads; certainly it has received as much applause. There is little doubt, however, that it has been outdistanced by “McGrew,” and I believe a case can be made that of the pair “McGrew” is a superior work.

What is it that gives this piece of verse so much staying power? Service saw it as a drama in three acts. In the first, he sets the scene, introduces the characters, and supplied the tension. A solo game is in progress (solo, which resembles pinochle, is rarely played today), and here we meet the villain, Dan McGrew, and his girlfriend, the faithless Lou. The door is flung open and a stranger, “dog dirty and loaded for bear,” stumbles into the bar, flings down a poke of gold, and stands everybody a drink. We don’t know who he is, but he gets our respect when he staggers over to the ragtime piano.

Now the second act opens, and it is here that the tale is lifted above the standard Western ballad. Service’s decision to tell the tale of McGrew’s villainy and Lou’s betrayal gives the story its power. He himself was a musician, self-taught on the piano, the banjo, the ukulele, the guitar, and the accordion. We can hear the piano in our minds as the ballad progresses. The man arrived from the creeks turns out to be a gifted musician (“My God How That Man Could Play!”). The music sets the scene in what Service calls the Great Alone: the ice-sheathed mountains, reflecting the soft blaze of the Aurora, tell the story of one man’s loneliness, a man driven by his own hunger for gold to the exclusion of all that is natural. The music brings back the memory of a home dominated by a woman’s love, a woman “true as heaven is true” and superimposed on those features is the ghastly rouged face of the strumpet clinging to McGrew. The music modulates to a softer tone followed by an intense feeling of rage and despair, and then, as McGrew coolly continues to play his hand, rises to a crescendo as the audience hears the cry for revenge hidden in the chords that crash to a climax.

The third act follows. The stranger whirls about on his piano stool, his eyes “blind with blood,” points to McGrew as a “hound of hell,” and the inevitable gun battle follows as the lights go out momentarily and a woman screams through the blackness. The two antagonists lie crumpled on the floor as Lou flings herself upon the body of the dying stranger, clutches him to her breast, and plants kisses on his brow.

Service, of course, has no intention of continuing with such a melodramatic and saccharine ending. That was never his style. He has a sardonic surprise: Lou’s embrace is simply a cover for her avarice. As the man from the creeks is breathing his last, she has been searching for the same poke he tilted on the bar a short time before. Service has the final line: “The woman that kissed him and pinched his poke was the lady that’s known as Lou.”

The twist ending was a Service trademark, more suited to his ballads than to his lyric poetry, which he continued to compose without any thought of publication while he went for long tramps in the woods with a book of poetry in his pocket, usually Kipling. One day, he was standing on the heights above Miles Canyon when a new verse popped into his mind. He called it “The Spell of the Yukon.” In the month that followed he wrote something every day during those lonely walks. “I bubbled verse like an artesian well,” he remembered. Then, suddenly, all inspiration ceased.

He did not realize that hidden away in his bureau drawer lay the seeds of future triumphs. He came upon his “miserable manuscript” one day and decided to show it to Mrs. De Gex, his landlady. She thought his rhymes were “not so dusty” and suggested he combine them into a pamphlet to send to his friends at Christmas: “it would be such a nice souvenir of the Yukon.” Of course, she remarked, he’d have to leave out the rougher poems—“McGrew” and “McGee”—and also such efforts as “My Madonna” and “The Harpy,” which reflected Service’s fascination with fallen women and the seamier side of life.

Since the bank had given him a hundred-dollar Christmas bonus, he decided to follow her suggestion and have a hundred copies printed to give to his friends as “my final gesture of literary impotence … my farewell to literature, a monument on the grave of my misguided Muse.” He was finished with poetry for good; he would study finance and become “a stuffy little banker.”

He could not foresee that this slim volume would be his epiphany: the mild bank clerk would be transformed, phoenix-like, into a figure of towering reputation for what was, in truth, a mere grab bag of verses old and new, some previously published, others resurrected and revised. In spite of the title, Songs of a Sourdough, half of the poems in the collection had nothing to do with the Yukon. Several, indeed, dealt with the Boer War. None of that seemed to matter to the three million readers who eventually bought the book as edition after edition rolled off the presses. More than half a century later the critic Arthur Phelps noted of Service that “no anthology of Canadian verse dare leave him out. No academic critic knows what to do with him. He has become an event in the working annals of Canada on his own terms.”

Service kept the “coarse” poems in the collection—the ones that Mrs. De Gex wanted him to leave out. He retained “The Harpy,” in which he wrote sympathetically about a prostitute from her own point of view, and “My Madonna,” where a painting of a woman from the streets ends up in a church being worshipped as the Virgin Mary. He was not an ardent feminist, but he did treat women with understanding. To him, the Yukon itself was feminine. In the opening line of “The Law of the Yukon” the land is “she.” Service sees her as a celibate earth mother longing for men who are “grit to the core” (“Them will I take to my bosom, them will I call my sons”).

Service’s Scottish heritage cautioned him to hedge his bet by laying off a half-interest in the book for fifty dollars to a fellow Scot who occasionally offered him a loan at 10 percent a month. The “village Shylock,” as Service called him, turned the offer down. “Who buys poetry in this blasted burg? … Ye can jist stick yer poetry up yer bonnie wee behind.” When later he learned what a fifty-dollar investment in Songs of a Sourdough might have brought him, Service joked, “I think it broke his heart.… I know,” he added, “it would have broken mine if I had been obliged to give half the dough that book brought me in royalties.”

Service typed out his selection of rhymes and sent it and a cheque to his father, now in Toronto, who peddled it to William Briggs’s Methodist Book and Publishing House, which did vanity work on the side. The poet almost immediately regretted this rash action. His inferiority complex convinced him that people would laugh at him when the book came out. “It would be the joke of the town.” He had wasted one hundred dollars.

He didn’t even bother to read the letter the publisher eventually sent. When he finally opened it, a cheque fell out; the firm was returning his money. Only when he read the letter did it dawn on him that he was being offered a contract to publish his work with a royalty of 10 percent on the list price. He could hardly believe it. “The words danced before my eyes … my whole being seemed lit up with rapture.” Service was sure that he must have a guardian angel overseeing his career. That guardian angel finally appeared in the guise of Robert Bond, a twenty-three-year-old salesman for the publisher who had been about to leave on his annual sales trip to the West when the firm’s literary editor handed him a set of proofs. “We’re bringing out a book of poetry for a man who lives in the Yukon. You’re going to the west coast; you may be able to sell some to the trade out there. It’s the author’s publication and we’re printing it for him. Try to sell some for him, if you can.”

Bond, who was already packed and leaving for the station, stuffed the proofs into his pocket and forgot about them until that night. Sitting in the diner with nothing else to read, he dipped into “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” He was so entertained that he forgot his meal and burst out laughing when he reached the final line. Across the aisle, a commercial traveller asked what he was laughing at.

“It’s poetry,” Bond told him, and the man’s face fell. “It’s unusual,” he explained, “and it’s Canadian and it might even sell.” He began to read the ballad aloud and as he read, his fellow passenger began to squirm in his chair and then, at the last line, howled with laughter. “He coughed till he choked,” Bond recounted later, “and had to leave the dining-car.”

In the smoking car after dinner, a crowd had gathered and pressed Bond to read the ballad. “When I finished,” he recalled, “bedlam broke loose—and everybody spoke at once. Some of the men even quoted lines that stuck in their memory.” Others, who had come in late, asked Bond to read the poem again. He did it several times before the night was over, so that by the time they reached Fort William he knew it by heart. He began to walk into bookstores to recite it. Whenever he was able to do that, the store ordered books.

When the first copies of Songs reached Bond in Revelstoke, he was appalled. “How I swore! It was a poor-looking thin book, bound in green cloth.” The company, disturbed by the frankness of some of the poems, had tried to shuck off responsibility by marking it “Author’s Edition.” To Bond the cover price of seventy-five cents was an insult; he had been quoting it to retailers at a dollar. With the first edition already on the verge of selling out, Bond urged his firm to buy the rights and sell it on a royalty basis. When the first royalty cheque arrived, Service thought there must be some mistake and wrote to ask how long the royalties might continue. Fifty years later, Bond told an interviewer, “I have no doubt he is still wondering, for certainly no Canadian poet, or possibly any poet has received as much as Mr. Service has received.”

Service near the end of his life would remark that he had made a million dollars out of Songs. He soon managed to increase the royalty rate from 10 percent to 15 and the publisher at once raised the cover price to one dollar, suggesting a future profit to Service of $450,000. But of course the cover price increased over the years, so that Service’s own estimate of a cool million is probably an understatement.

Only a minority of Service’s readers outside the Yukon realized that he had written the poems without ever having seen the Klondike. Most believed he had actually taken part in the great stampede, as a study of memoirs of that time makes clear. One respected author and jurist, the Honourable James Wickersham, wrote in Old Yukon that in Skagway in 1901, “in one of the banks, a gentlemanly clerk named Bob Service was introduced [to me].” Thames Williamson in Far North Country declared that “Service was in the Klondike during the fevered days of the gold rush.” Glenn Chesney Quiett made the same error in his Pay Dirt. In February 1934, Philip Gershel, aged seventy-one, claimed he was the original Rag Time Kid of Service’s best-known ballad. “I knew Dan McGrew and all the others,” he declared and went on to describe the Lady That’s Known as Lou as “a big blonde, tough but big-hearted.” Gershel said the shooting took place in the Monte Carlo Saloon; Mike Mahoney claimed it happened in the Dominion. “I was right there when it happened,” he insisted to an interviewer in 1936. He claimed that Lou was still alive and living in Dawson City. (James Mackay claimed that she was a cabaret performer who drowned when the Princess Sophia sank off Alaska—in 1918.) Mahoney, the hero of Merrill Denison’s book Klondike Mike, recited “Dan McGrew” so often he came to believe in it. When he was challenged at a Sourdough Convention in Seattle by Monte Snow, who had been in Dawson for all of the gold-rush period and knew that Mahoney’s story was fictitious, the assembly of old-timers gave Klondike Mike the greatest ovation of his life. They did not want to hear the truth.

Service himself felt that he ought to have been in the stampede and considered himself a bit of a charlatan because he was writing about events in which he had not taken part. In the fall of 1907, having spent three years with the bank, he was due for a three-month leave. He did not relish the idea because he knew it could lead to a reassignment that might take him away from the North. “That would be a catastrophe; I realized how much I loved the Yukon, and how something in my nature linked me to it. I would be heart-broken if I could not return. Besides, I wanted to write more about it, to interpret it. I felt I had another book in me, and would be desperate if I did not get a chance to do it.”

Fortunately, his guardian angel, this time in the form of the bank inspector, was on hand after Service took his holiday. “You’ll be sorry to hear you’re going back to the North. I have decided to send you to Dawson as teller.”

Service was more than relieved. “I was keen to get on the job. I wanted to write the story of the Yukon … and the essential story of the Yukon was that of the Klondike.… Here was my land.… I would be its interpreter because I was one with it. And this feeling has never left me … of all my life the eight years I spent there are the ones I would most like to live over.”

Dawson in 1908 had five times the population of Whitehorse but was on the way to becoming a ghost town. In the evenings, Service wandered abandoned streets, trying “to summon up the ghosts of the argonauts,” gathering material for another book, Ballads of a Cheechako. He was just far enough removed from the manic days of the stampede to stand back and see the romance, the tragedy, the adventure, and the folly. His verses sprang out of incidents that were common occurrences in the Dawson of that time: Clancy, the policeman, mushing into the north to bring back a crazed prospector; the Man from Eldorado hitting town, flinging his money away, and ending up in the gutter; Hard Luck Henry, who gets a message in an egg and tracks down the sender, only to find that she has been married for months (Dawson-bound eggs unfortunately were ripe with age). These themes were not fiction, as “McGrew” was. As a boy in Dawson, I watched Sergeant Cronkhite of the Mounted Police, his parka sugared with frost, mush into town with a crazy man in a straitjacket lashed to his sledge. As a teenager, working on the creeks, I saw a prospector on a binge light his cigar with a ten-dollar bill, fling all his loose change into the gutter, and lose his year’s take in a blackjack game. The eggs we ate, like Hard Luck Henry’s, came in over the ice packed in water glass, strong as cheese, orange as the setting sun.

My mother, then a kindergarten teacher, remembered Service strolling curiously about in the spring sunshine, peering at the boarded-up gaming houses and the shuttered dance halls. “He was a good mixer among men and spent a lot of time with sourdoughs, but we could never get him to any of our parties. ‘I’m not a party man,’ he would say. ‘Ask me sometime when you’re by yourselves.’ ”

He seldom attended any of the receptions or Government House affairs, and soon people got out of the habit of inviting him. When a distinguished visitor arrived in town, Service would have to be hunted down at the last moment, for they always insisted; and the poet, if pressed, dutifully made an appearance. My mother remembered how Earl Grey, the governor general, on a visit electrified Dawson by asking why Service hadn’t been on the guest list for a reception. “We had all forgotten how important the poet was.”

Service, who felt he had to undergo every type of experience, wangled permission to attend a hanging that fall. He stayed at the foot of the gibbet until the black flag went up and then, visibly unnerved, moved with uncertain step to the bank mess hall and downed a tumbler of whisky. It was decades before he could bring himself to compose a ballad based on that experience.

In one of his rare visits to the cottage where the kindergarten teachers lived, he discussed some of the new poems he was writing. “In his soft voice well modulated but strangely vibrant and emotional when he talked of the Yukon,” he read my mother parts of “The Ballad of Blasphemous Bill.” “I cannot say I was greatly impressed,” she remembered, “for it seemed to me a near duplicate of the Sam McGee story, and I said so.

“I mean it’s the same style—one man’s body stuffed in a fiery furnace—the other’s a frozen corpse sewn up and jammed in a coffin,” she told him.

“Exactly!” Service exclaimed. “That’s what I tried for. That’s the stuff the public wants. That’s what they pay for. And I mean to give it to them.”

Service’s thoughts, at this period, were always on his work. He danced with my mother once during one of his rare appearances at the Arctic Brotherhood Hall. In those days each dance number—waltz, two-step, fox trot, and medley—was followed by a long promenade around the floor. When the music stopped for such an interlude the absent-minded poet, deep in creation, forgot to remove his arm from my mother’s waist. As she recalled in I Married the Klondike, “We meandered, thus entwined, around the entire floor, and in those days a man’s arm around a lady’s waist meant a great deal more than it does now. The whole assembly noticed it and grinned and whispered until Service came out of his brown study.”

Working from midnight to three each morning, Service was able to finish the new book in four months. It consisted largely of ballads in the metre of “Dan McGrew” and “Sam McGee.” Service’s love of alliteration can be seen in the names of the leading characters: Pious Pete, Gum-Boot Ben, Hard Luck Henry. For his several character sketches of Klondike stereotypes—the Black Sheep, the Wood Cutter, the Prospector, and the Telegraph Operator—he chose a different rhythm:

I will not wash my face;

I will not brush my hair;

I “pig” around the place

There’s nobody to care.

Nothing but rock and tree;

Nothing but wood and stone;

Oh God! it’s hell to be

Alone, alone, alone.

I recall such a character when, at the age of six, I drifted with my family down the Yukon River from Whitehorse to Dawson. Above us on the bank stood a lonely cabin, and from it emerged its sole occupant, the telegraph operator. He called to us and insisted we stay for lunch—porcupine stew. When we took our leave and made our way down the bank to our poling boat, he followed. “Don’t go yet. Stay! Stay for dinner. Stay all night. Stay a week!” Every time I pick up Ballads of a Cheechako I think of him.

The Dawson of Service’s day was still crowded with men who had climbed the passes to reach their goal. No man caught the obsession or the fury of that moment in history better than Service had in his poem The Trail of ‘98—a phrase he embedded in the language. Here he used his words like drumbeats that seem to echo the steady tramp of those who plodded upward toward the summit—in a measured tread that came to be dubbed the Chilkoot Lockstep.

Never was seen such an army, pitiful, futile, unfit;

Never was seen such a spirit, manifold courage and grit;

Never has been such a cohort under one banner enrolled,

As surged to the ragged-edged Arctic, urged by the arch-tempter—Gold!

It is easy to see why so many of Service’s readers were convinced that the poet had been in the forefront of that army. As he himself put it, “It was written on the spot and reeking with reality.” He sent the manuscript to his publisher who promptly returned it, complaining of “the coarseness of the language and my lack of morality.” A brief struggle followed by telegraph, which Service won by threatening to offer the book to a rival publisher. Once published, the book became another best-seller.

Dawson City’s Front Street with its false-fronted buildings a few years before Service arrived. The literary gold he panned was better than any prospector’s.

Service’s poems, alas, did not impress the parents of a pretty young stenographer with whom he kept company. They did not marry. As my mother has recorded, “The report we had was that her family did not approve of Service. His wild verses upset them and, because of his themes, they were convinced that he drank.”

This attitude to Service’s work gives an insight into the publishing practices and taboos of the time. Lorne Pierce, one of the editors at the Methodist (later Ryerson) Press at the time and eventually his publisher, harboured “an aesthetic dislike for Service’s work” according to a paper given before the Bibliographical Society of Canada in 1996. As a book editor, Pierce dedicated himself and his company to publishing a Canadian literature cultivating “a sympathetic atmosphere in which the sublimest beauty, the sweetest music, the loftiest justice and the divine truth might be expected to take hold and flourish.”

That, of course, ran counter to everything that Service was producing, but what could his publisher do? To put it crudely, publishers needed the income and the international kudos. By the time his next royalty cheque arrived, Service had achieved his original plan of saving five thousand dollars. He immediately launched into a second plan. “Ten thousand would put me in a spot where I could thumb my nose at the world … having written two books I could now sit down and do nothing for the rest of my life.”

For the next two years he did just that. In the winter, Dawson vibrated with self-made entertainment: skating parties, bob-sledding, snowshoe treks, formal dinners, and two dances a week, “a glorious time—not much work, lots of fun, money flowing in.” But for Service it all began to pall. In his memoirs he portrays himself as a man too lazy to work, but it is clear that by late 1909 something was gnawing at him. On one of his jaunts up the Klondike Valley it came to him. Why not a novel about the gold rush? The idea, percolating in his mind, began to excite him. He would “recreate a past that otherwise would be lost forever.”

When the time came to start writing, however, he found he couldn’t do it. “My words came with difficulty. My imagination lagged. Something was wrong.” What he needed, he knew, was seclusion, but he could not find it in the bank. About this time he was offered a handsome promotion to become manager of the Whitehorse branch. Service recoiled. “It would worry me to death. I am a meek soul. I cannot give orders to others.” And he could not leave the Klondike with a novel germinating in his brain. On the spur of the moment, he told the bank manager that he would be leaving his job after the requisite three months’ notice.

His boss gave him a long look and asked how much he was making. About six thousand dollars a year from his books and one thousand from the bank, Service told him. There was a gasp: “Why, it’s more than I’m making myself.” And that was that.

Service needed a cabin in which to work and found one on Eighth Avenue overlooking the town. In later years it became a shrine, and I can still remember standing on the kitchen porch of our house across the street, watching Chappie Chapman’s big orange bus disgorge its newest load of Service fans. They had come down the river on the sternwheeler Casca to squeeze into the little room where he wrote his verse using a carpenter’s pencil on huge rolls of brown paper hung from the walls. It has since become an official heritage site, and each summer, in the front yard, an actor on contract to the Klondike Visitors Association recites the bard’s poems.

It was in this cabin that Service wrote his first novel, The Trail of ’98. Its main character is patterned on himself. “I made him a romantic dreamer … at odds with his environment … in short, like myself, he was destined to be a failure; but while I escaped by a fluke I took it out on my poor devil of a hero and gave him the works.” The name of his heroine, Berna, was taken from the label of a can of condensed milk. As Service described her, she “was purely imaginary and unimaginably pure.” (Briggs, his Methodist publisher, had urged him to make her “an inspiration to virtue.”) The novel itself, a best-seller in its time, is virtually unreadable today, the love scenes so saccharine as to cause nausea, the melodrama over the top, the dialogue unreal:

In this cabin on Eighth Avenue in Dawson, Service wrote some of his best-known work, using a carpenter’s pencil and sheets of brown paper tacked to the walls.

From under his bristling brows he glared at us. As he swayed there he minded me of an evil beast, a savage creature, a mad, desperate thing. He reeled in the doorway, and to steady himself put out his gloved hand. Then with a malignant laugh, the sneering laugh of a fiend, he stepped into the room.

“So! Seems as if I’d lighted on a pretty nest of lovebirds. Ho! Ho! My sweet! You’re not satisfied with one lover, you must have two …”

What worked for Service in rhyme sadly failed him in prose. Nevertheless, Hollywood bought the novel and made it into a film, starring Dolores del Rio as Berna.

Service, who never stopped counting his profits, finished the novel in April 1910, and terrified of losing his work in the mails decided to take it personally to his American publisher, Dodd, Mead, in New York. On the train east—the first time he had ever been in a Pullman—he was so rattled by the unaccustomed luxury that he left his wallet on his seat and found it gone with all his money. He wired New York to send fifty dollars to him in Chicago and lived out the intervening days on sixty-five cents—an apple here, a couple of doughnuts there. When he reached New York, his publisher was surprised that he looked so commonplace. “We expected you to arrive in mukluks and a parka driving a dog team down Fifth Avenue,” said one of the staff. “Why didn’t you? It would have been a great ad.”

After three months in New York, seeing the sights from Broadway to Chinatown and growing fat in the process, Service decided to get back in shape by taking to the road, as in the old days—a little stroll to New Orleans, staying in cheap hotels en route. The stormy weather put him off, and after three days he completed the trip to New Orleans by train. Then, on an impulse, he took a boat to Cuba where he put up at a chic hotel and lived a life of ease for three weeks.

There was no escape from the furnace-like heat and Service began to long “for the snow and tonic air of the North.” Lingering on the Prado one day, as he idly turned over the pages of an American magazine his eyes fell on an article titled “I Had a Good Mother.” Service, who paid so little attention to his blood relatives, suddenly thought, “I too had a perfectly good mother.” He realized that he hadn’t seen her for fifteen years, his father was dead, and the family had moved briefly to Toronto from Scotland and then to Vegreville, Alberta. Service—being Service—devised a sudden and dramatic storybook plan for a reunion. He would go straight to the family’s homestead unannounced and would walk in as if he’d never been separated from them. By evening he had the opening lines of greeting worked out: “How about a spot of tea? By the way, in case you don’t remember, I’m your first-born.”

He reached Vegreville in the late autumn with the snow already covering the ground, knocked on the frosted door of a frame farmhouse, and was greeted by a pretty girl. His sister? He had no way of knowing. He said he was an encyclopaedia salesman and she ushered him into a cozy but primitive kitchen. A little elderly woman who was washing dishes at the sink came forward, drying her hands. “Why, if it isn’t our Willie,” she said. As Service noted, “We Scotch are economical in our emotions. We exchanged the same conventional kiss we had indulged in when I left fifteen years before. My sisters were introduced and I pecked at their cheeks.” Then, following his own script, he asked, “What about a cup of tea, Ma? I could do with a spot.”

He spent the winter of 1910–11 roaming the prairie trails, usually walking twenty miles a day and bunking nightly with accommodating neighbours. By the time spring came he was again in superb physical condition. “I wanted to keep going till I reached the Land of the Midnight Sun,” he thought, so he went back to the homestead and told his family—the two youngest boys and three sisters—that he was returning to Dawson. “Are you crazy?” they asked. He could go anywhere: India, China, the South Seas and “you’re going back to a ghost town where you’ll be as lonely as hell.” Which, of course, is exactly what he longed for—“peace and quiet, to be far from the world.”

Having made up his mind, Service decided to go back the hard way—not by Pullman car, luxury liner, or paddlewheel steamer—but by the so-called Edmonton Trail, the 2,000-mile route that some of the gold seekers had opted for in ’98 to their eventual regret. The route followed the Mackenzie River almost to the rim of the Arctic Ocean and then curved west in a huge semicircle across the divide that separates the Mackenzie country from the Yukon, eventually reaching Dawson by the back door. The back-breaking effort in hauling boats and barges up and over the Mackenzie Mountains made the Chilkoot Pass seem like a pleasant outing. More men died, drowned, starved, or froze to death using this much vaunted “All-Canadian Route” than on any of the other trails to the Klondike. Not long before Service decided upon the venture, four Mounted Policemen on patrol near Fort McPherson had starved to death trying to reach Dawson. Service’s superb physical condition and his own guardian angel—luck—got him through.

Why did he put himself through it? No doubt because he was trying to prove himself. People thought he had toughed it out on the gold-rush trails. He still felt like a fraud among the genuine sourdoughs. This was his way of joining that exclusive fraternity. He was also hoping to soak up new material for another book of verse. More, he wanted to get as far from civilization as he could. In that he was certainly successful. In those days, this far-off corner of Canada was virtually unknown to anyone save the traders, the natives, and a handful of missionaries and Mounted Police. Service was equipping himself to pan untrammelled ground.

In late May 1911, he took the stagecoach from Edmonton to Athabasca Landing, hoping to get on the Hudson’s Bay Company’s flotilla travelling north. When he discovered the barges had left, he set out in pursuit by birchbark canoe. It took him three days to catch up. The flotilla took him to Fort McMurray, where they were welcomed with enthusiasm. The barge fleet was the first contact the residents had had with the outside world for a year. The festive air was dampened for Service by the local Indian agent, an ex-parson, who, on learning the poet’s destination was Dawson, shook his head solemnly and declared, “Young man, you’re going to your doom.”

A week later Service boarded the river steamer Grahame and almost confirmed the agent’s doom-saying when against the advice of an old-timer he dived into the swirling Athabasca River, was caught in the undertow, and was swept a mile downstream. He only saved himself by seizing an overhanging branch.

At Fort Smith, following a twenty-mile portage around a series of rapids, he took another steamer across Great Slave Lake to Fort Simpson, where he bought “the finest birch bark canoe in the North” from a veteran canoe maker. He christened her Coquette. The trip down the Mackenzie from Fort Simpson was marred by the discovery of the corpses of two trappers in a cabin, both dead of gunshot wounds—one a murder, the other a suicide, both the victims of cabin fever. To Service, the Mackenzie was a far more murderous river than the Yukon. “Its law was harder, its tribute higher. It killed most of those that I knew.” At Fort McPherson, he bought some flour and bacon, and here, at the mouth of the Peel River, an old man with a patriarchal white beard warned him against continuing his mad project. “Don’t! Don’t go on,” he said. “Go back the way you came like a good little boy.” The Mounted Police sergeant on duty had the same advice. “Don’t you do it. Just think of the Lost Patrol.” As Service put it, “I think he expected me to reconstruct the tragedy in verse; but I never like to write about realities, so The Ballad of the Lost Patrol was left ‘unperpetrated.’ ”

Faced with these warnings, Service worried about his planned trip up the Peel River and over the divide. In a few days, the sternwheeler that had brought him from Fort Simpson would leave on her return journey, and everybody was urging him to board it. He was tempted to follow that advice but could not bring himself to quit. “If you do it,” he told himself, “you’ll never respect yourself again.”