This is the story of Prince Leo, who left his home to find a wife and was never seen or heard of again. Leo, the eldest son of Gustav, a King of the Norselands, was a kind, generous Prince with hair the colour of ripe wheat and eyes the brilliant blue of cornflowers. Leo’s friendly manner made him popular with everyone who met him; however, the King, his father, was disappointed in his son.

‘Not every man can be born a Viking,’ said Queen Astrid to Gustav. ‘Not every man likes to fight and pillage and make merry all night long. Some men are drawn to the finer things of life. Leo happens to be one of them.’ Queen Astrid, who was manicuring her nails, flung back her strawberry-blonde hair as she dipped her fingers in a lotion of beeswax and lavender to soften her hands.

The King grunted, reluctant to argue with his wife.

The King’s problem was that, although Leo was the eldest of his three sons, the young man didn’t behave appropriately. That is, he didn’t stride about – like the other men in the King’s court – with long, strutting steps, and he didn’t thump his chest and bellow when he laughed. What’s more, Leo didn’t enjoy jousting on horseback. To the King’s dismay, his son had no talent, whatsoever, for duelling with swords or for wielding a dagger in close combat. It was bad enough that Leo didn’t behave as a true Viking should – fierce as an eagle but with the cunning of a snake – but what hurt the King the most was that Leo simply didn’t care.

In fact, the only sharp instruments he enjoyed holding were the kitchen knives he used for creating recipes with the Queens’s chef and a pair of old secateurs for pruning roses in the Queen’s garden. Most humiliating of all, unless it was as calm and still as a village pond, Leo was petrified of the sea.

The king shuddered at his son’s peculiar behaviour, cringing at the thought that he, Gustav, a King of the Norselands, could have produced such a lily-livered man.

‘Recipes and flowers indeed! And he’s fearful of the sea. There isn’t a Viking alive who doesn’t love the sea!’ Gustav mumbled into his beard as Astrid rubbed sprigs of rosemary into her hair to clean and perfume it. ‘This is Astrid’s doing. If she didn’t dote on Leo so, if she didn’t make such a fuss of the boy, he wouldn’t be such a disgrace.’

***

At last, when Leo had given up sword play and wrestling altogether and refused to set foot on a boat, Red Norman, a messenger from the King of Orkney, arrived at Gustav’s court with a message. Gustav listened carefully to the messenger from the Orcadian King and, as he did so, an idea seeded in his mind. If he could behave with the ruthlessness of a true Viking, if he could only hold his nerve, he knew that before long his problem with his eldest son would be solved. Without further ado, Gustav ordered that the very next evening a banquet would be held in the Great Hall in honour of Red Norman of Rousay. And at the banquet, Gustav, a King of the Norselands would make an important announcement.

There was nothing more pleasing to Leo than preparing for a royal banquet at short notice. He quickly sharpened his cooking knives and then, in collaboration with the Queen’s chef, prepared a menu for the sumptuous feast which they cooked the next day. Ten maid-servants helped them in the kitchen and on the evening of the banquet, serving girls streamed out of the royal kitchens carrying cauldrons of creamy lobster soup. They brought out trays of crab-meat on rye bread, followed by platters of cured salmon seasoned with dill and spice. For pudding there was cloudberry pie served with thimbles of cloudberry liqueur, that reminded those sipping it of the first hint of autumn after long days of midsummer sun. Everyone present relished the meal. When they had eaten their fill and were salting their tongues on coils of liquorice, Leo brought out his harp and sang.

The voice that came out of the King’s eldest son was strong and melodious. What’s more it was reassuring, even though the song Leo sang brought to mind a blue moon on a star-tossed night. Leo sang about lost love and sad farewells. He sang with all his heart, so that it seemed to Queen Astrid that his voice glittered – darting and flashing like the Northern Lights. Astrid blushed, delighted, while the down growing in the crease of the King’s back stiffened.

Gustav pushed back his chair and stood up. ‘I have an announcement to make,’ he said, bringing Leo’s singing to a halt. ‘An announcement!’

Before Gustav could say any more, the guests in the Great Hall burst into rapturous applause – not for the King but for Leo.

‘A toast!’ someone shouted. ‘A toast for Prince Leo!’

There was loud thumping of chests, the raising of glasses and drunken roars of ‘Encore! Bravo! Another song, Leo!’

‘I have an announcement to make,’ the King thundered.

Gradually, everyone fell silent. Everyone, that is, except for the Queen, who was asking one of her ladies-in-waiting to fetch a glass of fruit cordial to soothe Leo’s throat.

‘As you know already,’ said Gustav, ‘this banquet is in honour of Red Norman, who is here on behalf of the King of Orkney. What none of you are aware of is the important message Norman has brought with him.’ The King paused to gulp down some liqueur, thrilled that everyone wanted to hear more.

Gustav growled and coughed. He took another swig of cloudberry, and smiled bashfully at his son. ‘Orkney wants it to be known,’ he said at last, ‘that he’s looking for husbands for three of his daughters. I’ve decided to send Leo to woo them. It would be to our advantage if the ties between the Norselands and Orkney were cemented in marriage.’

Leo’s brothers patted him on the back as if he’d already returned home with an Orcadian bride. They didn’t seem to notice that their brother looked on bewildered.

‘I want you to go, Leo,’ the King said, ‘because I’m convinced that marriage will be the making of you. Only a true Viking can win the heart of an Orkney Princess, so you must become a true Viking indeed!’

At these words the Queen grew pale. Her fingers fumbled with a silver pendant around her neck and as she stared at the King, the glaze of tears in her eyes brought a chill to his heart.

Clutching the pendant, the Queen rose unsteadily to her feet. ‘May Leo return safely with a wife who will love him always,’ she declared. ‘A wife who can see him for what he is: a strong, gentle man, the sweetest and most loving of men!’ Then, raising her glass, the Queen drank a toast to her son.

The King decided that Prince Leo would leave Norway with Red Norman by the end of the week. Leo hastily put his affairs in order and on the morning of his departure went to the Queen’s chamber to say goodbye.

‘I’ve a feeling your journey is going to be difficult,’ the Queen said, touching Leo’s cheek. ‘Perhaps we shan’t see each other again. So before you leave, I want to remind you that nature has made you a patient man, Leo. You are patient and caring, yet there are some women who can’t be won with patience, my dear. Don’t be disheartened. I believe that after you’ve passed through great danger, you’ll find true love.’

‘I don’t want to go,’ Leo sighed. ‘I want to stay with you here, mother.’

Unable to bear the sight of tears welling up in her son’s eyes, the Queen turned away to hold back her own tears. When she was herself again, Astrid faced her son: ‘The world isn’t always a happy place, Leo. At times like this, it seems very dismal indeed. Remember how much I love you and heed what I’m going to tell you.’

Astrid stroked the token to Freya – the goddess of love, who soars through the heavens on a chariot hauled by black cats – she wore around her neck. ‘Remember that the sea is your friend, my son. At times, she can be as jealous as a woman determined to claim you as her own. But she can also soothe you, Leo, and reward you. You may not realise this but if you make friends with her, she’ll look after you. And when your time of danger comes, remember, ask her for help and she’ll protect you.’

Drawing her son closer, the Queen kissed him before handing him the locket of Freya to wear in her memory.

***

For over a year, Leo was a guest at Trumland Castle – home of the King of Orkney. His gentle ways made him a favourite with the four Princesses, who listened enraptured to the stories he sang with his harp. Delilah and Jezebel tossed teasing glances in his direction, but it was Jael that Leo loved. He was drawn to the glint of midnight in her eyes, and when she smiled at him, that hint of tenderness on her face that showed that she liked him.

The Prince waited patiently until the two eldest Princesses were married before approaching Jael. Then, on the first day of summer, when the sun was out on Rousay and the wind was soft as a baby’s sigh, Leo made a crown of pansies for the Princess.

‘Heartsease,’ he murmured, placing the wreath on Jael’s head. ‘Will you ease my heart, sweet Princess, by doing me the honour of marrying me?’

Jael roared with laughter, shaking so violently that she split a seam of her red dress, revealing a ribbon of flesh.

‘O Leo!’ she squirmed, dabbing her eyes with a sleeve. ‘Please don’t go wobbly on me like the rest of those fools. You’re my friend, you idiot! Don’t make me throw you off the island like I’ve done all the others.’

Undeterred, Leo trailed behind Jael – a pale, faithful Labrador.

Later that morning he fed her cakes he’d baked in the royal kitchens, cakes made of apple and carrot and walnut. Then, in the afternoon, he made her a bouquet of wild poppies with blue-eyed borage and red campion. And when Leo’s heart was full to overflowing, he rubbed the silver locket he wore and asked of Freya: ‘Why doesn’t she love me? Why doesn’t Jael of Orkney love me and go back to the Norselands with me as my bride?’

As dusk fell and the island of Rousay, bathed in grey pearly light, shimmered in the sea, Leo pleaded with Jael to reconsider his offer. She turned her back on him yet again. Dejected, Leo sang out his sorrow to the sea in a voice so clear and true that the rocks around Rousay shivered when they heard his song.

Jael, however, was still unmoved. In fact, the next day, when the two of them went for a walk on Scaqouy Head, she warned Leo never to speak of marriage again. But Leo couldn’t help himself. Before dusk had fallen, he proposed once again.

‘Is that man simple?’ Jael’s other suitors muttered to each other as they saw Leo emerging from the royal kitchens with a tray of fairy cakes for the Princess. ‘Can’t he see that he’ll never win her love? Can’t he see that his case is hopeless and he should move over to make room for us?’

That’s what they said. And yet, while countless suitors were dismissed from the island and rejected outright, Leo was allowed to stay – as long as he behaved the way Jael wanted.

At last the day came when Leo discovered the Princess prowling the garden of Trumland Castle. She paced between the rose bushes, catching her dress on thorns. Every now and again she shook the dress loose, leaving a trail of rose petals behind her.

Leo picked one up and placed it against his cheek. It was from a bush his mother loved, a wild rambling rose, which grew in pink clusters against the west wall of her summer house in Norseland. ‘This petal is an omen from Freya,’ Leo thought. ‘An omen that my time has come.’

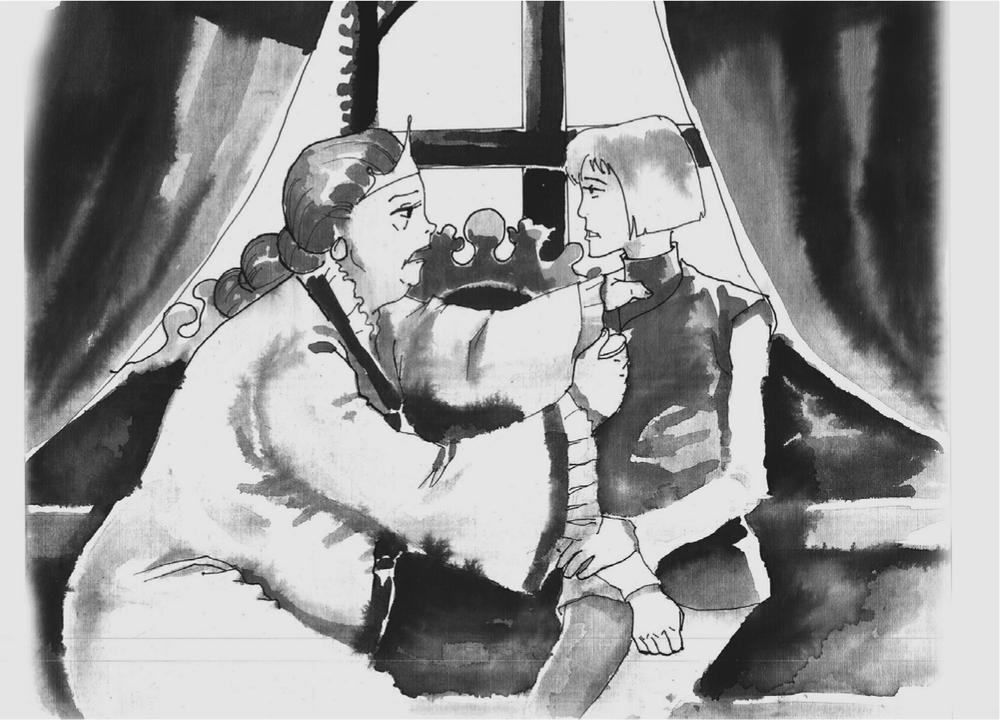

The Prince blocked Jael’s path, placed a hand on her shoulder, and asked for the third time: ‘Will you marry me, Orkney Princess?’

‘Blast you, Leo!’

Leo thought he was about to be slapped but to his surprise, after scrutinising him, Jael said petulantly, ‘Very well, Leo of Norseland. I’ll marry you. But first you must make me a wedding dress from the feathers of puffins.’

Leo was overjoyed. ‘I’ll do anything you want, Jael, anything at all. Nothing will give me greater pleasure than to find feathers to adorn you for our wedding. The goddess of love glides through the sky in a cloak made of hawk’s wings.’

With those words Leo ran to find a boat to sail to Wyre Island where a colony of puffins lived. ‘When I come back,’ he promised the Princess, ‘with the help of Freya, my love for you will be such that you will love me in return.’

***

If he’d had more sense, Leo would have waited for the ferry to Wyre that morning, instead of rushing off. But eager to marry Jael and return home quickly after a year on Rousay, he brushed aside his usual nervousness around water and leapt into a rowing boat, paddling furiously towards Wyre. He didn’t notice storm clouds gathering, and as a stranger to Orkney he didn’t yet understand the curious ways of the Rousay currents. Leo was in love and in too much of a hurry to notice that anything was wrong. Until, halfway between Wyre and Rousay, a clap of thunder rocked the sea and turbulent waves thrust him off course towards the island of Egilsay – an island ringed by sharp granite rocks.

Wet and shivering, Leo cried out as lightening tore open the sky to reveal the faces of goblins laughing at him. The thunder roared again, this time with a low, ominous rumble, as if the mere sight of Leo struggling on the sea made it angry.

Terrified, the Prince called out a second time as the wind swept the boat towards the rocks off Egilsay. ‘Wind and rain stop!’ he begged. ‘Stop! For I must go to Wyre to make a dress of puffin’s feathers for my Orkney bride.’

If the storm heard Leo, it failed to respond. It flung the boat closer to Egilsay. Leo thrust the oars against a slab of rock to push himself to safety but first one and then the second oar snapped as the boat flooded with water. Convinced that he was about to die, the Prince clutched the locket around his neck to sing a last song.

His voice rose, a church bell sounding through the storm, through lashing rain and biting gale. Leo sang for his family in the Norselands, the tall pines and glaciers of his home. Then, he sang for Jael whose careless love had led him to his fate. The gale seemed to answer him in Astrid’s voice: a mother’s howl of grief as her son, his boat smashing against rocks, begins his journey from one world to the next.

‘Mother, is that you?’ Leo asked the wind. ‘Are you there?’

Believing that he could hear his mother’s voice, Leo remembered what she had said as she kissed him goodbye. Leo remembered her words and begged the sea for mercy.

The wind and rain paid no heed to his plea but the sea, sensing his desperation, stilled her waves. Having listened to Leo’s songs over the past year and been soothed by them, she swallowed him deep down into her belly.

At first, Leo didn’t know what was happening to him. Swaddled in an element he detested, he thought he was drowning, being swept towards a watery grave, when all at once the sea seemed to cradle him, buoying him, till he floated up to see the sky again.

The storm had passed, the air was still, and yet Leo felt completely different. He was different. He saw that his skin, which had been white as the snow on the mountains of the Norselands, though still pale, was rough as a pumice stone. His hands, which had once teased tunes from a harp, were clumsy, fat flippers. His feet were large fins. What’s more, his beautiful golden hair had gone, replaced by a stubble of bristles on his chin. Leo would not have recognised himself had it not been for his mother’s silver locket coiled around one of the two tusks that sprang from where his teeth had been.

‘Has it come to this? Have I become a walrus?’ he asked, refusing to believe what his eyes told him. ‘Is this hulk what has become of Leo of the Norselands?’

Leo’s tears fell on Egilsay rock. They fell until the granite crags glistened beneath the midday sun. As always, sadness moved Leo to sing. He raised his curved tusks to the sky and opened his mouth to give his sorrow to the sea. He cleared his throat and breathed in deeply but instead of a glorious voice ringing out clear and true, a large croak came out. Leo sounded like an old Viking burping after a heavy meal.

‘What has become of my voice?’ He opened his mouth again to sing but the same undignified noise rang out louder than a donkey’s fart.

‘Not only have I become a walrus, I’ve also lost the gift I treasure most. My home is the sea, yet I’ve never liked the sea. I much prefer living on land. Not that I’m ungrateful, mind you …’

The pools of Egilsay rock rose as Leo filled them with his tears. They rose till they covered the tip of the highest granite peak and ran into the sea. The people of Rousay saw the island of Egilsay disappear under a river of tears. On the nearby island of Wyre, the white puffins whose feathers Jael had wanted for her wedding dress, scattered in alarm. Finally, the people of Rousay saw a fat grey walrus, its head bowed in grief, slowly swim away.

***

Leo travelled to the lands of the north to find creatures that looked like him: creatures with skins as tough as elephants and faces wizened by the wind. After several days, he came across a family of walruses looking for food beside the island of Greenland. They welcomed Leo into their circle, nibbling the stubble on his chin in greeting.

‘How did you get that silver locket around your tusk?’ asked a curious young walrus who hadn’t yet grown tusks. He was anxious to know the background of the wandering walrus that had just joined them.

‘I’m not really one of you,’ Leo confessed, stifling a sob. ‘I’m Leo – a Prince of the Norselands. I went to Orkney to find a wife and became as I am when the sea saved my life.’

‘You don’t seem very pleased to be alive,’ grunted an old bull walrus with long, grey bristles on his chin.

‘I don’t feel at home at sea,’ Leo replied. ‘I prefer dry land. What’s more, since my change, I’ve lost my voice. I can’t sing anymore and I love singing.’

‘Of course you can’t sing like those humans do,’ explained the old bull walrus. ‘We walruses don’t sing that type of song. We have our own music.’

His relatives nodded in agreement.

‘But I love singing,’ said Leo. ‘Even more than I love cooking and gardening. Singing makes me who I am.’

‘Who you were,’ said the old walrus, shaking his head sadly.

‘You’ll not be able to sing as a walrus, I’m afraid. Not unless you find your voice again or find a mate. Then you’ll sing a walrus song, which will be the making of you.’

The family of walruses waddled around Leo to comfort him. They stroked his back, massaging it softly to make him feel better. As they rubbed and stroked and grunted and snuffled, they put their heads together to think of a plan to help the walrus Prince.

‘We could take him back to Orkney to search for his old voice there,’ one suggested.

‘We could look inside a conch shell,’ said another. ‘They hold the music of the sea.’

‘I have the answer,’ said the old walrus, grunting in excitement.

‘Whale can help. The whale who travels with the fish-woman. The woman who once walked on land.’

Quickly, the old walrus told Leo about Ajuba, the fisherman’s daughter, who had been sent to sea by her village and had become a mermaid. Ajuba swam the seven seas with her best friend Whale, who occasionally returned to Greenland to visit relatives.

‘Whale should be coming home shortly,’ explained the walrus, ‘and when she does, I’ll ask her to take you to the fisherman’s daughter. If anyone can help you, I’m sure she can.’

For seven days Leo waited for Whale to appear. He waited with the family of walruses who tried their best to make him feel at home in the sea. They lazed about in the warm summer sunshine, splashing in the waters of Greenland. They guzzled clams and crabs, then feasted on sea-worms tossed with sea cucumbers and cabbage. In the afternoon they relaxed on cushions of seaweed, burping happily to the sun.

If it hadn’t been for the fact that he could no longer sing, Leo might have tolerated his new life in his ungainly new body. The mounds of blubber beneath his skin, which had turned pinkish-brown in the sun, kept him gloriously warm in icy water. And day by day, he began to realise that his lumbering bulk made him less anxious about being in water. It was the sea that had saved him and now, when he plunged in the element he’d once been frighted of, instead of feeling cold and clumsy, he was graceful and at ease.

No, life as a walrus wasn’t bad; especially since Leo was enjoying spending time with a big-eyed walrus who had taken a liking to him. As she scrubbed and pummelled his back, the frustrations of his stay on Rousay were rubbed away and, gradually, Leo forgot his love for Jael.

At the end of a week, Leo bade farewell to the walruses and swam towards an iceberg where he’d been told that Whale would be waiting for him. When she saw Leo, Whale looked at him suspiciously.

‘Why do you want to meet my friend Ajuba?’ she asked, wary of anyone who might intrude on her friendship with the fisherman’s daughter or anyone who might hurt her.

‘I need help to find my voice,’ Leo said. ‘I lost it when I became a walrus and I’m not at all happy without it.’

‘I’m not sure that Ajuba’s the person you’re after. I’m not sure if anyone can help you for that matter.’

The look of desolation that swept over Leo’s grizzled face at the suggestion that no one might be able to help him surprised Whale. So much so that, being a fundamentally kind-hearted creature, she added quickly: ‘I’m not sure if Ajuba will be able to help you, but maybe it’ll be worth your while talking to her.’

‘Pray tell me, where does my lady dwell?’

‘I left my lady in the Gulf of Siam. Your lady,’ Whale sniffed, ‘is with a band of sea gypsies. She says they’re worshipping her – though how pouring bottles of whisky and lotus flower wine into the sea can be described as worship I don’t know. I’m happy to take you to her if that’s what you want. But whether it’ll do you any good or not …’

‘I need to meet her,’ Leo insisted. ‘I don’t think I have any other choice at the moment.’

And so it was that with a swish of their tails, the walrus Prince and Whale began the long journey to the Gulf of Siam.

***

They travelled across the choppy waters of the Bay of Biscay, around the coast of Africa, to the emerald land of Siam where the people live by an inner grace directed by the sea and stars. There, they discovered Ajuba floating on warm water, her face turned up to the sun.

Up till that moment, Leo, having only been a walrus for a short time, had never seen a mermaid. He was startled by what he saw. Ajuba was almost as tall as Whale. Her skin shone like polished black coral and her long fish’s tail, which could move with the strength of a herd of sea lions, swished seductively in the turquoise water.

The fisherman’s daughter gave the walrus Prince a lazy smile of welcome and, as she did so, Leo sensed that if anyone could help him find his voice again then Ajuba was that person.

‘Well,’ she said, when she’d listened to Leo’s story, ‘I think the first thing we must do is investigate your talent for singing. When you walked on land, what did people say your voice was like?’

Leo paused to think. Eventually, he said: ‘At times they used to say that I sang like a nightingale. I’ve also heard it said that my voice is like a tinkling silver bell. But my mother claims that when I sing she is enchanted, overcome with the magical splendour of the Northern Lights.’

‘Anything else?’ Ajuba probed, sensitive to the wobble in Leo’s voice when he mentioned his mother.

The walrus Prince snuffled. ‘Sometimes,’ he sighed, ‘when I was really inspired, people used to say that it was as if I was singing to Freya – the goddess of love. They said I used to sing to her with the voice of a bird born in paradise,’

‘A bird of paradise,’ Ajuba murmured, scratching her scalp to help her think. ‘I’m not sure about this, but it’s worth a try …’

Without further ado she dived underwater, cutting through currents to the boats of the sea gypsies. The gypsy children hailed her, calling to their parents to come and look at the black goddess. Soon the decks were crowded with people throwing paper flowers at Ajuba. There were old men and women, naked brown children, men wrapped in sarongs, and sun-kissed women suckling their babies.

Ajuba silenced them with a wave of her hand. ‘I want you to do something for me,’ she asked, as a hush descended over the honey-brown people. ‘Will you fetch me the feathers of birds of paradise? Twenty-one glorious feathers; one for every year the walrus Prince has lived.’

Delighted to do the bidding of their ebony goddess, the sea gypsies pulled up anchor and sailed away in their brightly coloured boats. A warm wind blew them gently along the coast until they arrived at their destination: a sheltered cove that led to a jungle on the mainland of Siam.

When night fell, a group of gypsies waded to shore guided by the fluorescence of the sea and the light of the stars. They each carried a birdcage, for they knew that in the jungle – in the safety of quiet glades where fruit and flowers grew – lived many birds of paradise.

The gypsies placed the cages on the forest floor, leaving a trail of sweetened nuts to every door. At a signal from their leader, they retreated to the shadows to wait for their prey. Before long, they heard a bird of paradise singing. And then a second bird and a third – their voices shining in the air with the brilliance of fireflies.

As the first bird hopped closer, its song filled the glade with a thread of golden sound that made the leaves of trees tremble, while insects vibrated in chorus. A second bird, then a third, dropped to the forest floor and, between bursts of song, they nibbled the nuts and pecked their way into captivity. By dawn, every single one of the twenty-one cages was filled with a bird beating its wings against bars.

Anxious not to prolong their captivity, the leader of the gypsies plucked a tail feather from each of them before allowing them to fly free again. The birds flew into the air, their wings lighting up the morning sky.

***

The sea gypsies returned to the Gulf of Siam to find Ajuba tickling the walrus Prince with a palm leaf. Leo croaked happily between chuckles. Then, diving underwater, he circled Ajuba. As he did so, he made walrus sounds: a clicking and drumming from the back of his mouth, a strange, rhythmic music that walruses make when they find a mate. Though his body was still cumbersome, it didn’t seem to matter anymore; with Ajuba at his side, Leo felt beautiful again – alive and gifted with love.

‘Do you want these feathers?’ the captain of the sea gypsies called out to Ajuba.

‘Do you still want your voice back?’ Ajuba asked Leo.

The walrus Prince nodded, and so Ajuba wove a necklace with the twenty-one feathers. She twisted the necklace around Leo’s neck, then wound it around his tusks so that, intertwined with his mother’s locket, it hung as a garland fluttering on Leo’s chest.

‘Try and sing something now,’ Ajuba suggested.

Leo cleared his throat and opened his mouth, filling his lungs with a deep breath, the way he’d always done before singing at King Gustav’s castle. Leo cleared his throat again. He coughed. Then, after filling his lungs a second time, he opened his mouth and the silver-feathered necklace snapped.

An unearthly sound filled the Gulf of Siam. It rose like a wave sweeping across the shore to herald the sun and moon laughing at each other across the sky. Yet it wasn’t a frightening noise, for the sea gypsies who heard it say it was as sweet as a rainbow dripping honey.

To their amazement, they watched the walrus Prince become a man again: a man with the torso of a prince and the tail of an enormous kingfish. They say they saw the walrus Prince swim with their black goddess and a whale far out to sea. And they say (though how they know this I’m not sure) that in a cold faraway kingdom of pine trees and glaciers, a Queen called Astrid heard the walrus Prince’s song, and knew that her son was happy at last.