This is the story of the Fish-man who guards the Purple Lake at the bottom of the sea. They say the Fish-man was not always a monstrous creature with the legs and arms of a man and the head of a fish, but was once a beautiful boy called Musa from a region now known as Senegal. Musa came from the savannah lands of West Africa, where tall grasses blow in a landscape dotted with baobab trees.

Musa’s parents scraped a living by growing millet and rice on a patch of land. His mother and father worked hard to raise their seven children: they laboured on the fields of their rich neighbours, sold drinking water to passing travellers, and the children, doing their part, gathered firewood to sell at the market every day.

Harvest after harvest, the family lived happily without much fat on their bones – until one year the rains failed. Across the savannah, grass shrivelled yellow, scorched dry by the sun. A coat of red dust settled on everything. The drought became so severe that wild animals forgot their differences and gathered around waterholes to wet their lips. When the animals began to migrate in search of water, Musa’s father and mother began to plan how best to survive.

First, they sold their most prized possession: a goat whose milk the children drank once a week. Then, Musa’s mother exchanged the gold earrings she wore at harvest celebrations for a sack of grain. When the grain was finished, Musa’s father sold his favourite smock, embroidered in silver and gold thread, which he wore at weddings.

In the end there was nothing left to sell, and all the while little Musa, unaware that disaster crouched close by waiting to pounce on his family, played with his friends.

‘We have to take Musa to a home where he will be fed properly,’ said his father, watching the six-year-old kicking a ball made of leaves and animal hide. ‘Even though hunger hasn’t gnawed at his bones yet, our son will feel it soon if he remains with us.’

Musa’s mother remained silent, afraid that if she spoke too soon, her emotions would betray her. Then, taking a deep breath, she said, ‘Perhaps your uncle, the storyteller, will take him. I understand he is rich but kind. And since all his children are grown-up now, he may enjoy having a small boy at his side again.’

Her husband agreed.

Before Musa left home, his mother cradled him in her arms the way she used to when he was still a baby. The next morning when he awoke, she bathed her youngest son – rubbing oil on his skin till he gleamed, a black scorpion glinting in sunlight.

‘Goodbye my son,’ she said, after feeding Musa his favourite breakfast of millet porridge. ‘You’re going far away today, but I shall always remain close to you. Do you understand?’

Musa nodded. He couldn’t really make sense of what his mother was saying, but he could see from the glitter of tears in her eyes that she was sad.

‘I shall remain close to you, Musa,’ his mother repeated. ‘So close, in fact, that every now and again I shall visit you in your dreams.’

The woman watched Musa leave the compound, his head erect, walking beside his father. When she lost sight of him, the tears she had been holding back began to fall.

Father and son walked for miles across the savannah lands until the farmer took to carrying Musa on his shoulders. Occasionally they heard the cawing of geese flying north and saw antelopes leaping across the horizon. The child, thrilled to be away from home, looked gleefully at everything around him. He heard baboons screeching in alarm as savannah hawks slowly circled the sky.

Three days later, the travellers approached the village where Musa’s rich great-uncle, the storyteller, lived with his wives and children.

‘Before I take you into my uncle’s compound, there is something I want to give you,’ the farmer said to Musa. ‘Just like you and my father before me, I am the youngest son in my family. There is a tradition in our family,’ he said, removing a red amulet from his pocket, ‘that this should be given to the youngest boy in our line when he leaves home. It’s yours Musa. Look after it carefully because it has magic properties.’

The farmer tied the amulet firmly around his son’s neck and then told the story behind it. ‘It’s said that our ancestors were Moors, my son, a people who travelled south in search of farmland. Before we came here, we conquered a land across the sea. One of our line found his wife with the help of a woman who was a bird by day and took human form at night. The amulet around your neck contains her feathers. They will bring you good luck, Musa. Guard the amulet carefully and always remember who you are: a precious child of the soil, the son of an honourable but humble farmer.’

It was hard to tell how much Musa understood of what his father was saying to him. After all, he was only six years old and, though he was clever and hoped never to bring shame to his family, he was still a child. But as he waved his father goodbye his hand held the amulet, and he believed he would hold fast to his father’s words: he was his father’s son, a precious child of the soil.

***

A few days after Musa’s arrival at his great-uncle’s compound, the rains came – falling in fat drops like eggs smashing on the ground. The flamboyant trees flowered in showers of scarlet, and the sweet smell of frangipani wafted from inside the old man’s compound throughout the village. Musa had never seen such abundance in his life. His great-uncle’s granaries were loaded with sacks of corn, millet and rice, and each of his three wives cooked meat every day.

Everyone was kind to Musa, admiring his intelligence and commenting on the beauty of his appearance. ‘Look how bright his blue-black eyes are,’ women whispered. ‘And look how straight and strong his limbs are growing,’ said passers-by as they watched Musa running through the village.

The boy enjoyed living in his great-uncle’s compound. He looked after the goats and ran errands for his aunts. For the most part, he was pleased with his new life. But sometimes at night, when mosquitoes disturbed his sleep and tree frogs croaked noisily, Musa remembered the family he had left behind and cried himself to sleep. Whenever this happened, his mother appeared in his dreams, singing the lullabies she’d once sung him when he was a baby.

On the second anniversary of his arrival at his great-uncle’s house, the old man summoned Musa to sit beside him at the entrance to his room. ‘I’ve been watching you,’ the old man said, gazing at Musa through milky eyes. ‘And I like your ways. You’re modest and truthful, a credit to the family. I’d like to help you, but as you know I’ve already allocated my land to my sons. My only regret is that I have no one to teach the art of storytelling to. Would you like to learn, Musa?’

‘But I am a child of the soil,’ the boy replied, ‘the son of a humble farmer.’

‘Just like I was when I started out. It’s often people like us who tell the best stories. Would you like to learn how to tell a story?’

Musa said that he would.

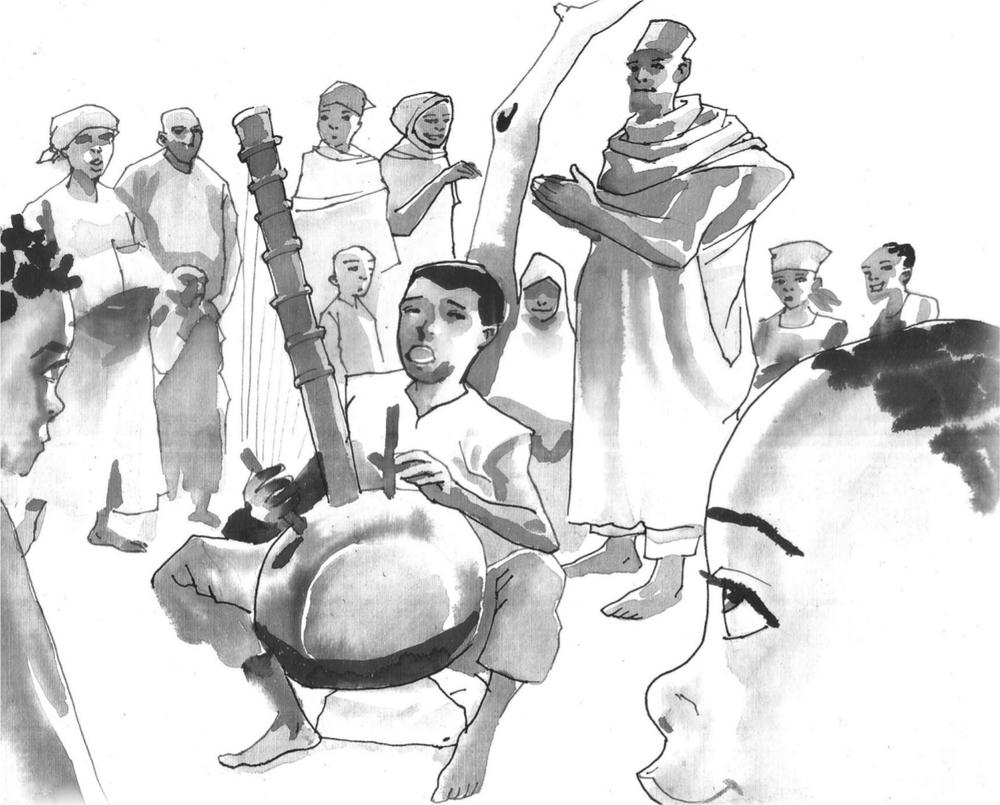

Every day after that, when he had finished herding goats and running errands, and had swept the compound clean, Musa joined the old man for lessons in storytelling. To begin with, he was given a kora to play – a large gourd of an instrument with many strings. His fingers learned how to pluck chords, nimbly stretching to make the sound of running water. Musa learned how to beat the side of the kora in imitation of armies marching to war.

Through listening to the old man’s words, Musa learned to sing refrains within stories; to sing and play like a young woman smiling, a lioness prowling or a young man hunting.

‘You’re an excellent student,’ said the old man. ‘I believe that in time you’ll become a master kora player and people will come to you to learn.’

Soon Musa became so adept with the instrument that his great-uncle asked him to accompany him when he performed at weddings. While the old man told stories that made the gathering laugh and then cry, Musa, dressed in fine embroidered clothes, sang melodious refrains. Strumming and plucking, he gently teased music from the gourd; music so moving that when the wedding guests heard it, they showered money over Musa.

One day, late in the afternoon, the old man summoned his great-nephew to sit down beside him. ‘It is time you learned our stories,’ he declared. ‘It’s time you moved on from simply singing my refrains.’

Musa was delighted. Hour after hour he sat with his great-uncle learning the stories of West African peoples. He laughed at the antics of Ananse the spider- man, folk hero of the Ashanti. He memorised the tales of travelling Fulani herdsmen, the stories of Wolof and Mandinka warriors and, finally, the adventures of magic hunters from Guinea, who fly by night and converse with spirits in daylight. Musa had never been happier in his life.

If his favourite Aunt happened to ask him for a story, he would pluck it like a feather from the amulet around his neck, and then grooming it with words, fluff it out, until the feather grew into a mighty pair of wings that flew to the listener like a golden bird. Every night, hugging the amulet, Musa recited the story that his great-uncle had taught him that day, repeating it till the rhythm of his words was exactly like that of the old man.

Musa became so enchanted by the stories he was learning that as he slept he dreamed he was a magic hunter, a victorious warrior. He was Musa, the son of a magnificent, powerful King; Musa, a great hero.

You wouldn’t have noticed watching him grow into a young man that there was anything amiss in his character. At sixteen, Musa was given some of the old man’s cattle to look after. He found them grazing- land, where the grass was moist with dew. Yet when he returned home from the savannah, there seemed less of the old Musa about him, and more of something new.

‘He’s becoming a man,’ thought his favourite Aunt, as she handed him a bowl of cassava and guinea fowl. ‘He keeps more of his heart to himself now.’

No one seemed to realise that Musa’s love of stories was changing him. Alone with the cattle on the grasslands, he became the heroes he sang about. He was a warrior with a burning sword, a hunter with a spear that killed lions. He fought with the greatest of men, outwitting them. Then, after he’d forced them to bow down before him, men and women, old and young, threw garlands at his feet.

No one seemed to realise, when he sang at weddings, that the gleam of conviction in Musa’s eyes was a sign that a craving for greatness was gnawing at his bones. ‘Who respects a man who sweeps the yard like a woman and leads a handful of cattle to graze?’ he asked himself. ‘Or for that matter, who respects the son of a farmer, when those who are remembered are men who’ve performed extraordinary deeds? More than anything in the world I want to be a warrior!’

Before long, there wasn’t a task he did in the old man’s compound that pleased him. Whether he was feeding husks to goats or leading cattle to graze, he felt ashamed, believing that such chores were beneath him. Eventually, the old man, sensing the unease within Musa, called him to his side.

‘Musa,’ he said gently, ‘you haven’t been yourself for some time. Now that you’re old enough to travel on your own, I think you should visit your family.’

Musa nodded, excited at the old man’s suggestion. The old man gave Musa a gold necklace to take as a gift to his mother and a magnificent smock in blue, red and green to give to his father. ‘Walk carefully on your journey home,’ he said, after giving Musa his blessing. ‘And when your visit is over and you’re yourself again, you’re very welcome to return to my house.’

***

The next day Musa set off on his journey. But instead of taking the path that would lead him back to his father’s village, he walked due south to seek advice from Nana – a wise woman who lived deep in the forest and understood the wishes of the gods.

When he arrived at the forest’s edge, Musa, pretending that his steel cutlass was a silver sword, slashed the undergrowth, notching a mark on the trees so he would be able to find his way out again. Cutting away creepers, he plunged deeper and deeper into the jungle, little knowing that a thousand hidden eyes were spying on him, warning Nana of his progress.

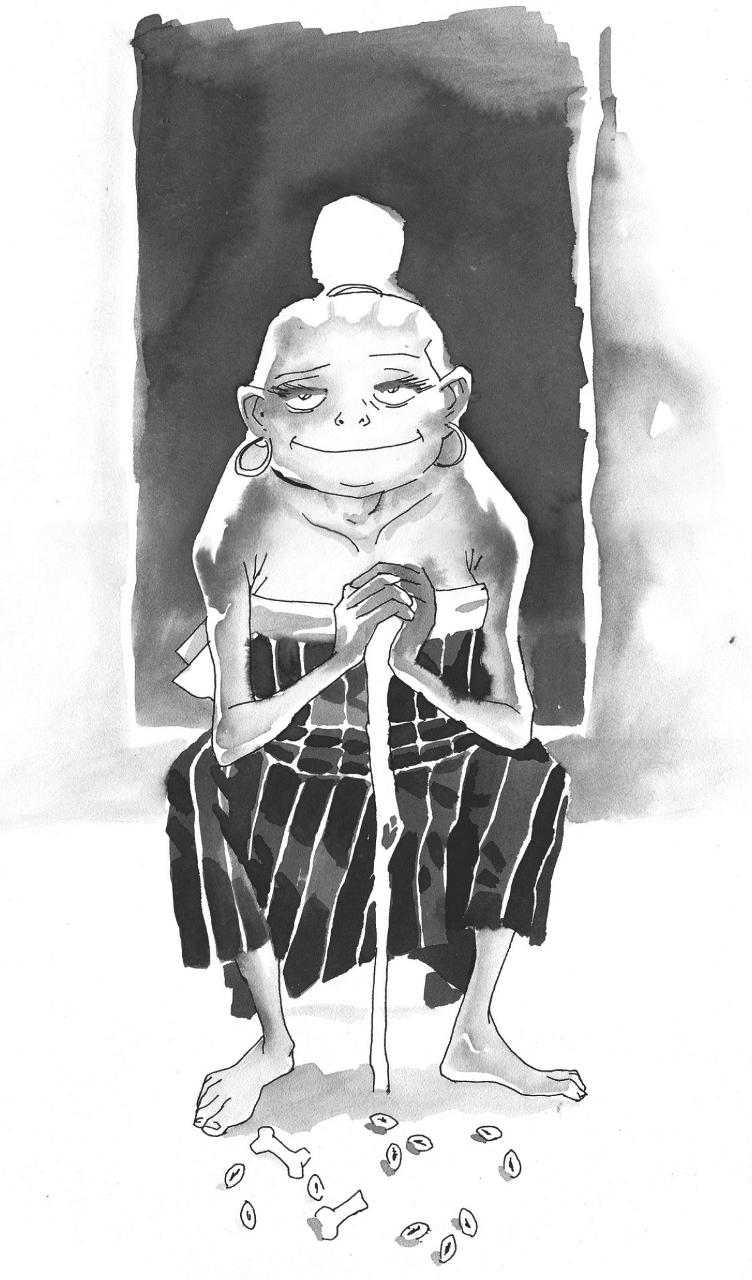

On the third day of his journey, Musa stumbled into a clearing where a thatched hut stood beside a crooked Nim tree. Sitting in the shade of the tree was a wizened woman, her grey hair plaited. She was throwing cowry shells to look into the future, and as the shells fell, she sang a rhyme to herself:

‘Birds fly and spiders creep,

Men sometimes cry

But Musa shall weep.’

The old woman looked up and smiled. ‘Musa,’ she said, ‘I was expecting you over an hour ago. What can I do for you?’

Without further ado, Musa sat down beneath the Nim tree and opened up his heart. ‘I want to be famous,’ he said. ‘I want my dreams of glory to come true. Tell me, Nana, how can I make that happen? How can I make my name known?’

‘Are you sure that’s what you really want?’

‘Oh yes,’ Musa sighed.

Nana asked him to throw the cowry shells. He shook them in both his hands, blew his breath over them for good luck, and then flung them to the ground.

Nana shook her head sadly, for spread out before her like fragments of speckled eggshells was Musa’s future. ‘You have a gift for storytelling Musa, be satisfied,’ she urged. ‘Soon your fame will spread, and you will become a master kora player and a great storyteller. Go home, Musa.’

‘But I want to be a great hunter and warrior,’ the young man replied.

Nana asked him to throw the cowry shells a second time and once again she told him to go home and be satisfied with his lot.

‘Why won’t you help me?’ Musa cried. ‘I know I’m the son of a humble farmer, but that shouldn’t stop you from telling me how I can become a magnificent warrior so that I too will be someone people sing about.’

‘So you won’t heed my warning? Didn’t you hear my song, Musa?’

The old woman repeated the rhyme, but this time she sang slowly so that every word of the song could be heard:

‘Don’t you know it’s dangerous to tamper with your destiny?’ she said. ‘Put aside your childish dreams. Go home a man, my son!’

Having travelled so deeply into the forest, Musa couldn’t turn his back on his dreams. So at last, realising that nothing she said would dissuade him, Nana asked him to throw the shells a third time.

After carefully weighing up what the cowries were telling her, Nana said: ‘In the savannah lands near your home, Musa, lives a magic elephant, who many warriors have tried to destroy. This elephant has a name: Imoro. He’s as black as ebony and as strong as twenty hippopotamuses. His only weakness is that he can’t resist wild honey. If you succeed in killing him, Musa, you must grind his tusks to powder and then drink them with milk. Then you’ll have all the power you need to perform extraordinary deeds. But be careful,’ Nana added. ‘Hold your amulet close when you’re near Imoro, for should you fail in your task your fate will be fearful indeed.’

Musa thanked the old woman for her advice and following the trail he’d made, found his way out of the forest. A week later, he reached a town near the village where his parents lived and headed for the market. He looked around until he found what he was searching for: a table laden with jars of wild honey.

‘Come and buy, come and buy,’ a woman sitting at the stall yelled as she suckled her baby.

‘Will you give me all the honey that you have in exchange for this trinket?’ Musa asked. He opened the package that his great-uncle had asked him to give to his mother.

The trader’s eyes widened at the sight of such a chunky gold necklace.

‘I want every single jar of your honey,’ Musa explained, ‘and a cart and ox to pull it.’

The woman stared at Musa, shifting her baby from one breast to the other. ‘Aren’t you the child of Musa Baba?’ she asked, mentioning the name of Musa’s father. ‘Aren’t you the child he sent away during the great drought?’

‘Indeed I’m not,’ Musa replied.

‘Are you sure? Your face looks just like Musa Baba’s when he was younger, and your hands remind me of his before they grew rough tilling soil.’

‘I assure you, I don’t know who you’re talking about,’ said Musa. ‘Will you or won’t you sell me your honey?’

‘Of course,’ the woman said, quickly pocketing the necklace. She then called a boy to her side who arranged for all the honey to be placed on an ox-drawn cart.

Musa left the market, pulling the ox and cart behind him. After a couple of miles, he stopped at the roadside to drink cold water from a calabash. As he quenched his thirst, he heard the plaintive cry of an old man singing to a kora. Musa followed the sound till he found its source. The man, sitting beneath a flowering frangipani, was playing a silver- studded kora, the most beautiful instrument Musa had ever seen.

‘Will you give me your kora in exchange for this outfit?’ Musa asked, unpacking the hand-woven smock in blue, red and green that his great-uncle had asked him to give to his father.

The old man studied Musa’s face carefully. ‘Aren’t you the son of Musa and Meta Baba, who was sent away and is now a kora player?’ he enquired, naming Musa’s parents. ‘Your face is like his and so is your voice. In fact, when I saw you walking towards me, I thought Musa Baba had become young once again.’

‘I don’t know who you’re talking about,’ Musa said. ‘Will you or won’t you sell me your kora?’

‘I can hardly refuse,’ replied the old man. ‘Age has cracked my voice, and I shall soon need a fine smock to wear with my shroud. You may take this kora with pleasure.’

Satisfied with his purchases, Musa began the long journey deep into the savannah lands, to perform the deed that would make him famous; the deed that would make him the greatest warrior of all time.

There are places in West Africa where few men have walked, which echo with the hum of another world. Places where the songs of birds and the cries of animals sound strange because they are swept along by a cold, dry wind that blows from the Sahara. In one such space the grass, rustling uneasily, listens to the tread of a new step. It is Musa, silver kora slung over his shoulder, pulling the ox-cart of wild honey. Musa is tired and thirsty and glistens with sweat.

Unloading his cargo, he ties the ox to a tree and begins digging a hole. He lines the cavity with smooth, flat stones and when he has finished, pours in jar after jar of wild honey.

‘What is this man doing and what is his mission here?’ ask invisible spectators behind twitching grasses. They have never seen this before, a man emptying honey into a deep hole.

Soon, ants, smelling the sweet scent, cluster around the rim; with them come hornets and flies. Musa sits beneath the tree and begins singing to his kora. His voice cuts through the air with chords that drive the insects away.

The wind carries Musa’s message to birds, who sing it to every animal in the savannah. Lions, leopards and antelopes hear the song. They pass the message on to crocodiles and buffalo, till eventually it reaches the animal for which it is intended: the black elephant, Imoro, wallowing in a pool of water.

‘Your friend Musa invites you to a feast of wild honey,’ the animals cry. ‘He is sitting beside a tree waiting for you. Come quickly, Imoro, for the honey is good.’

Imoro, resplendent in his black skin, his white tusks gleaming in the sun, slowly rises from the pool. He steps out, following a bird who takes him to Musa.

The young man singing with the voice of a friend invites Imoro, the magic elephant, to eat. At first the animal is suspicious. Men have tried to trick him before but no one has ever presented him with his favourite food of wild honey. Imoro sniffs Musa’s scent and steps back. He sniffs again. What he senses confirms what he hears: the soothing balm of a young man’s music.

Imoro steps forward licking the basin of honey from the rim to the centre. Very soon all the honey is eaten and, kneeling down in gratitude, he wraps his trunk around Musa’s neck and caresses him.

At once, the young man’s voice becomes like that of a mother singing her child to sleep – the kora, a fountain trickling in the background. And while Imoro nuzzles Musa’s neck, stroking the red amulet, the young man is thinking, ‘First I must kill him. Then I must cut off his tusks, grind them to powder and drink them with milk, so that at last I will be the greatest of all warriors.’

Imoro’s eyes are closing. He is almost asleep. He dozes as Musa prepares to strike.

***

Musa set the kora aside and slowly inched his hand behind his back to where he had hidden a cutlass. Imoro’s eyes flickered open and then shut again, the way eyes often do when closing in sleep. Musa raised his arm, the cutlass glinting.

Just at the moment he was about to slam the weapon on Imoro’s head, the elephant opened its eyes again. The trunk, caressing Musa’s neck, jerked and as it did so, the amulet around Musa’s neck tore open, tumbling to the ground.

The cutlass came crashing down but instead of wounding Imoro, it tore a gaping hole in the earth. Realising that he had been tricked, Imoro shrieked with rage. He shrieked a second time, his tusks poised, his trunk about to dash Musa to the ground.

‘Magic amulet,’ the young man cried, petrified. ‘Help me! Magic bird who helped my ancestor, please come to my aid. Imoro, the magic elephant, is about to kill me!’

Three golden feathers from the amulet fluttered into life, and all at once became a gigantic golden eagle. Musa didn’t know which to be more frightened of: the shining bird or the black elephant. Both were enormous and both stood, side by side, glaring at him.

It was the eagle who spoke first and in the voice of the Orcadian Queen, Romilly. ‘Musa,’ she said, ‘you’ve brought shame to the family I’ve protected for years. I never imagined when I befriended your ancestor that one day I would be called to defend a man who dared forsake his family. What vain dreams of glory have possessed you, Musa? What foolish fantasies have led you to this?’

Musa trembled before the eagle and the elephant, and for the first time in years he longed to feel the touch of his mother’s hand and hear the voice of his father speaking. Even though he had pretended not to know them, Musa would have gladly exchanged his dreams of glory to be back in his family compound again.

‘I’d like to crush you to death,’ trumpeted Imoro, ‘but the eagle here says she has a better punishment in mind for you.’

‘Indeed,’ said the bird. ‘You wanted to be a warrior Musa, and now you will become one. Hidden in the Indian Ocean at the bottom of a mountain range is the Purple Lake. Your task will be to guard the lake with a sword made of a thousand shark’s teeth. You will stay there, alone and underwater, until the gods finally take pity on you.’

Grabbing hold of him by the wrists, the golden eagle carried Musa across the African continent, casting a dark shadow as she flew over the desert. When she reached an expanse of water, she circled until her eagle eyes saw the Purple Lake below. Then, from hundreds of feet up in the sky, she cast Musa into the sea.

Musa turned and twisted, somersaulting, convinced that his life was over. He turned and, as he flipped over a third time, he dropped the red amulet. He tumbled through dark clouds, hurtling down to the sea. As soon as he touched the water, he turned into the Fish-man: a monstrous creature with human arms and legs, and the body and head of a fish.

Musa languished in his watery prison beside the Purple Lake. He was grateful, to begin with, that his life had been spared. But as the lake snarled and snapped at him like a bad tempered dog, he grew lonely and yearned for friendship. And yet if anything – be it a smiling dolphin, a porpoise, or a laughing clownfish – came close to the lake, Musa’s friendly nature became possessed by a warrior spirit and he became the Fish-man. And then, waving the sword of shark’s teeth, he chased everything away; even though deep in his heart what he wanted most in the world was a friend.

Day after day he wept into the lake, which spat back at him angrily. ‘If only I had known how hollow the life of a warrior can be,’ he cried. ‘If I had known, I would have been content as a storyteller. No one told me it would be so lonely fighting everything in sight.’

What’s more, remembering his love for the kora, Musa tried to make one out of reeds and conch shells. But his hands, hardened by wielding the sword, broke the strings and he wept more bitterly.

At last the day came when Ajuba, the fisherman’s daughter, swam over the lake with her friend, Whale. She dropped a whale’s carbuncle into the Purple Lake to find the path to where her father lay buried by the sea.

A hissing serpent sprang from the lake. Musa, who was fast asleep, was woken up by the serpent’s voice. Ajuba was the first human he had seen during his life as the Fish-man. He wanted to talk to her. He wanted to hear the latest news of the land of men. But just as soon as this desire for friendship welled up within him, the warrior spirit possessed him again and, wielding the sword of a thousand shark’s teeth, he chased Ajuba and Whale away.

Musa returned to the lake crying. He was so distressed that he lifted his sword over his head and threw it into the Purple Lake. Then he knelt down, begging the gods to take pity on him. The hissing serpent reared up again, swaying from side to side.

‘Go home, Musa,’ she said. ‘You have served your time. Go back home.’

‘But how can I return?’ he asked.

‘Swim to the surface. The Bird-woman is waiting up there to take you home again.’

Musa did as he was told. The moment he breathed air again, his true nature returned to him and his fish-body fell away. He was Musa, a handsome young man once again, and circling above him was Romilly the golden eagle. She hauled Musa up in to the sky and then carried him back to his father’s village.

No one could believe their eyes when they saw Musa walking through the compound gates. They had given him up for dead. Musa’s mother threw her arms around him, delighted he was home again. And his father, now a very old man, ordered a cow to be killed in thanks for his son’s return.

The family celebrated for three days and on the fourth day Musa’s great-uncle arrived, laden with gifts. He brought cattle and goats and fabulous cloths for Musa’s mother and father. Most important of all, he gave the young man a new kora so that he could return to storytelling.

Musa lived to be an old man and, just as Nana had foretold with the cowry shells, he became a famous storyteller and a master kora player. One of his most popular stories is the tale of the Fish-man, which he claims is a true story. No one believes him, except for his wife Binta. Only she knows that whenever Musa washes in the sea, tiny silver fish scales appear on his back. Thankfully, they live a long way from the sea.