2

A TERRIBLE TORRENT OF FIRE

NEW YORK, 1835

“How shall I record the events of last night, or how to attempt to describe the most awful calamity which has ever visited the United States?” former New York mayor Phillip Hone wrote after his city’s big fire the week before Christmas. “I am fatigued in body, disturbed in mind, and my fancy filled with images of horror which my pen is inadequate to describe.”

The weather, as people in Boston knew all too well, often plays an important role in major fires. It’s hard to imagine a worse time for a fire than December 16 and 17, 1835. “The night was bitterly cold—seventeen degrees below zero,” an eyewitness named William Callender wrote, “and the wind blew a hurricane.”

At about 9:00 P.M. that Friday, William Hayes, a watchman patrolling the streets of lower Manhattan, smelled smoke. He summoned other watchmen and they traced the smoke to the five-story Comstock & Adams hardware store on Merchant Street, near where the East River meets New York Harbor.

“We managed to force open the door,” Hayes said later. “We found the whole interior of the building in flames from cellar to roof and I can tell you we shut that door mighty quick. Almost immediately the flames broke through the roof. It was the most awful night I ever saw.”

That building was in the wholesale dry goods and hardware district, where merchants who supplied shops in New York and other cities stored merchandise such as tea, coffee, dresses, lace, hats, and lead. The district’s six- and seven-story brick warehouses had iron shutters on the windows to keep out thieves. And they had copper roofs, which wouldn’t catch fire if firebrands from a nearby burning building landed on them. This night would test just how well those safeguards worked.

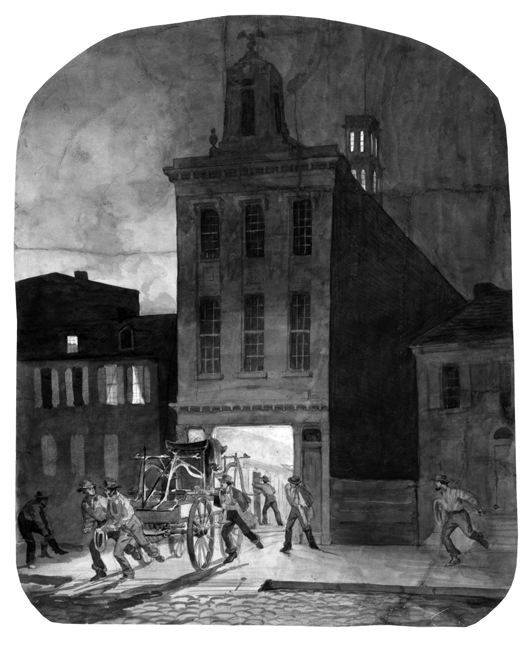

This print shows firemen in the nineteenth century pulling an engine to a fire. [LOC, USZC4-6029]

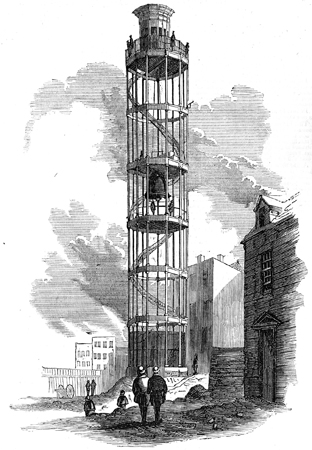

A watchman alerted the fire sentinel stationed in the cupola atop City Hall. The sentinel rang a big iron bell to summon volunteer firefighters. He signaled the burning building’s location by the number of peals and by hanging a lantern on the side of the cupola facing the fire. Church bells and fire-bell towers across the city repeated the alarm.

New York City, occupying just lower Manhattan Island at that time, had a population of 300,000 people. After the Erie Canal opened in 1825, New York had become the center of American commerce and business. Its 98-year-old volunteer fire department was one of the country’s biggest and best trained. Unlike Philadelphia’s and Boston’s blue-blooded firefighters, New York’s fifteen hundred volunteers weren’t prominent citizens, but working-class men. They served under full-time fire chief “Handsome Jim” Gulick.

The department’s equipment included 49 water-pump engines, called pumpers, with names such as Eagle 13, Oceanus, Black Joke, Old Honey Bee, and Lady Washington. The pump engine was a recent innovation. It didn’t need to be filled by buckets of water. The pump had a suction hose to draw water from a well, cistern, or other source. The department also had five hose carts and six hook and ladder carts. Responding to fires, the men pulled their carts and dashed through the streets at breakneck speeds.

Volunteer firefighters, unlike today’s professionals, didn’t sleep at their firehouses. When an alarm sounded, they had to run to their stations and grab their equipment. It took the first company, Engine No. 1, ten minutes to reach Merchant Street.

Iron fire tower in nineteenth-century New York City. [LOC, USZ62-73758]

Wells provided New York’s water, but that night they were frozen solid. The firefighters had to chop holes in the ice covering the East River. Then they connected hoses from pumper to pumper. Black Joke Engine Company No. 33 drew water from the river and pumped it to Chatham Engine Company No. 2, which pumped it to Engine Company No. 13, nearly four hundred feet from the river. But before the water reached the nozzleman at the end of the hose, it turned to icy slush. Without water, the firefighters could do little and the fire quickly spread.

The flames in the warehouses, recalled volunteer firefighter Gabriel O. Disoway, made the closed iron shutters shine “with glowing redness, until at last forced open by the uncontrollable enemy. Within, they represented the appearance of an immense iron furnace in full blast.” The heat exceeded 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, melting shutters and copper roofs.

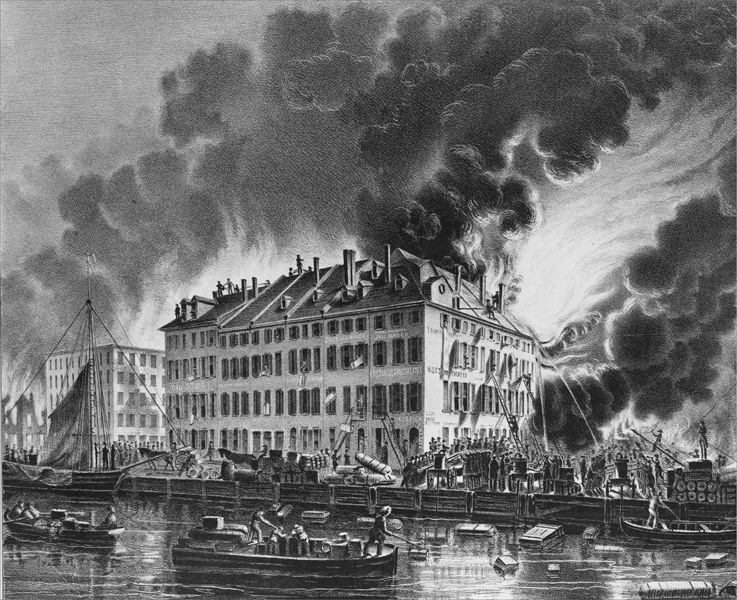

Nathaniel Currier’s lithograph of the first night of the big blaze sold thousands of copies in just a few days. [LOC, USZ62-2553]

By 12:30 A.M., the wind had driven the fire north to Wall Street. Then, as now, it was the heart of New York’s business district. “I stood at the corner of Wall and Pearl Street, where there is an open space like a funnel,” William Callender recalled. “The fire in great sheets of flame leaped across that space, cavorting around in maddening fury.”

A lithograph by Nathaniel Currier showing a view of the great fire from the water. [LOC, USZ62-50387]

Confident that the new three-story marble Merchants’ Exchange wouldn’t burn, people filled it with merchandise saved from burning warehouses and stores. But soon the Merchants’ Exchange as well as the nearby post office, banks, and churches were ablaze. “Street after street caught the terrible torrent,” observed writer Augustine E. Costello, “until acre after acre was booming an ocean of flame.”

Thousands of rowdy people watched. Two were killed. One person burned to death, and a mob lynched a man caught setting a fire. While many citizens helped firefighters, some stole hats, wine, and other merchandise that was piled in the streets. The police arrested three hundred people for looting. The less ambitious got drunk on stolen liquor and cheered the spectacular fire.

Turpentine stored in burning warehouses by the river exploded. “The water looked like a sea of blood,” wrote Costello. “Clouds of smoke, like dark mountains suddenly rising in the air, were succeeded by long banners of flame.”

Mayor Cornelius Lawrence was worried the blaze would spread north of Wall Street to the residential neighborhoods. A firebreak, he decided, might stop it. Sailors and marines from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, across the East River, used kegs of gunpowder to blow up several buildings on Exchange Place. The firebreak worked. But below Wall Street, the blaze lasted eight more hours, dying only when nothing was left to burn.

The city’s financial and commercial district—674 buildings on 17 city blocks—was smoldering rubble. “The heart of the city seemed to have ceased to exist,” observed Costello. “Of business there was none. New York was stricken as with paralysis.”

The estimated financial loss was as high as forty million dollars. That would be about one billion dollars in today’s money. Unable to pay all the claims, 23 of the city’s 26 fire insurance companies went bankrupt. Without insurance money to replace losses, many other businesses failed. By destroying the center of American commerce, some historians believe, New York’s Great Fire of 1835 added to the economic problems that a year later caused the worst recession the young nation had experienced.

This is a painting by the Italian-born artist Nicolino Calyo, an eyewitness to the fire. [New York City Fire Museum]

City officials and insurance companies wanted a reliable water supply to make New York safer. Construction of the Croton Water System began in 1837. Five years and twelve million dollars later, New York had the world’s biggest, most modern water system. Some 35 million gallons of water a day from reservoirs 41 miles north of the city flowed through iron pipes to fortress-like receiving reservoirs on Manhattan Island. The Croton Water System, like the Erie Canal before it and the Brooklyn Bridge after it, was one of the nineteenth century’s great engineering feats.

A Currier & Ives depiction of New York several years after the fire. [LOC, DIG-pga-03183]