5

FIRE ON THE WATER

NEW YORK, 1904

“There was never a happier party than we were when we boarded the boat Wednesday morning,” said Anna Weber, recalling her family laughing and talking the morning of June 15, before an excursion on the General Slocum.

Anna and her husband, two children, and six other relatives, all dressed in their best Sunday clothing, were joining thirteen hundred people for the St. Mark’s Lutheran Church’s seventeenth annual Sunday school excursion to Long Island. Many of these people attended St. Mark’s and lived nearby in a small, close-knit German immigrant neighborhood on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

The General Slocum, a popular excursion boat owned by the Knickerbocker Steamship Company, was a white pine and oak vessel three stories tall and 250 feet long. It had three decks—the lower main deck, the middle promenade deck, and the open-air hurricane deck, a nautical term for a steamboat’s breezy top deck. In the middle of the ship, a pair of tall pale yellow smokestacks pointed skyward. And on each side, paddle wheels 35 feet in diameter pushed the ship through the water at a top speed of about 15 knots, or about 17 miles per hour.

The General Slocum was a popular New York excursion ship. [Mariners’ Museum]

After the Slocum pulled away from the Third Street dock, it steamed up the wide East River between Manhattan and Brooklyn. At the stern, or back, of the promenade deck, a seven-piece band led by George J. Maurer played popular German and American songs such as “Vienna Swallows” and “Swanee River.” The passengers, a third of whom were age twenty or younger, danced, explored the ship, or leaned on the wooden railing, waving at people onshore.

New York City schoolchildren similar to those who perished on the Slocum. [LOC, LC-DIG-ggbain-02319]

Since the Slocum was launched 13 years earlier, William Van Schaick had been its captain. In the pilothouse on the promenade deck, Captain Van Schaick watched his two pilots steer the vessel toward Hell Gate, where the river channel narrowed and the currents were treacherous. As the Slocum steamed ahead at top speed, a boy appeared in the pilothouse doorway and interrupted the captain’s concentration.

The 12-year-old passenger, Frank Perditsky, told the captain there was a fire on the lower deck. “Get the hell out of here and mind your own business!” Captain Van Schaick yelled, thinking this was a prank. The captain then turned his attention back to the river.

Meanwhile, a deckhand named John Coakley tried to appear calm as he searched for Ed Flanagan, the Slocum’s first mate and the second in command. A few minutes earlier, Coakley had been drinking a beer in the saloon, when another boy told him about the smoke. Coakley traced it to a storage room in the bow, or front, of the ship. When he opened the storage room’s door, a fire smoldering in hay from a packing crate leaped to life. Coakley, leaving the door open, hurried to find the first mate.

After just a couple of minutes, Flanagan, Coakley, and several other crewmen returned. By then, nourished by oxygen flowing through the open door, the flames had spread to the stairs. The men grabbed a hose connected to a standpipe, but for some reason, no water came out. This was their only attempt to put out the fire. The Slocum’s 22-man crew had never held fire drills or been trained for emergencies.

Passengers soon noticed something was wrong. “I saw smoke coming up a narrow gangway leading from the lower main deck,” said the Reverend George C. F. Haas, St. Mark’s pastor. He was with his wife, 13-year-old daughter, sister, sister-in-law, and 3-year-old nephew. “I thought at first that the smoke might be blowing that way from the galley, where I know they were preparing to cook the clam chowder, but the smoke speedily increased in volume and I soon realized that it was something more serious.”

This steamship beneath the Brooklyn Bridge on the East River appears to be the General Slocum. [LOC, USZ62-59950]

Other passengers were having too much fun to notice. Dozens of children and their mothers had gathered for ice cream on the lower main deck, just below the pilothouse. Suddenly, “there was a roar as though a cannon had been shot off,” recalled Clara Steur, one of the passengers, “and the entire bow of the boat was one sheet of flames.”

Then “the flames burst out right near us,” said 14-year-old John Tischner, who was eating ice cream with a friend. “Everybody seemed to be yelling ‘Fire!’ and I saw a lot of women with their hair and dresses burning jump into the river.”

Ten minutes after discovering the blaze, First Mate Flanagan reported it to the captain. Van Schaick later explained that he started down the stairs, but “the fire drove me back. It was sweeping up from below like a tornado.”

Nicholas Balser, who was with his wife, children, and several other relatives, said he “thought that the boat would put into shore at once, but it seemed fully five minutes or more before she swung inshore. By this time, the scene was terrifying.”

Captain Van Schaick didn’t turn the Slocum toward shore, he later said, for fear of spreading the fire to the oil tanks and warehouses along the river. The captain decided to beach the ship a mile upriver, on North Brother Island. It was deserted except for Riverside Hospital, an isolated facility for people with typhoid, tuberculosis, and other infectious or contagious diseases. He estimated it would take three minutes to reach the island.

As the Slocum raced upriver, the headwind fanned the flames toward the stern. The steamship, like many wooden vessels, had been painted with linseed oil and turpentine to keep the wood from drying out, but these combustible liquids also made the wood burn faster.

“Sheets of flame followed the roiling clouds of smoke, and the fearful rush began to the sides of the boat,” said Joseph Halphusen, St. Mark’s sexton. “Women and children were thrown down and trampled on. The crew offered the passengers little help. It seemed to me that the crew of the boat lost their heads—they were undisciplined, and did not do what sane men would have done to stay the panic and restore order.”

The engineers kept shoveling coal into the ship’s steam boiler, while the captain and pilots stayed in the pilothouse. Everyone else was on their own.

Passengers who grabbed the ship’s five hundred Never-Sink life preservers soon discovered they were useless. John Kircher, who was not on the boat, related his wife’s account of what happened to their youngest daughter, Elsie. “Thinking the little girl would be perfectly safe with the preserver on, she lifted her to the rail and dropped her over the side. She waited for Elsie to come up, but the child never appeared. She had sunk as though a stone were tied to her.” The life preservers were old and rotten.

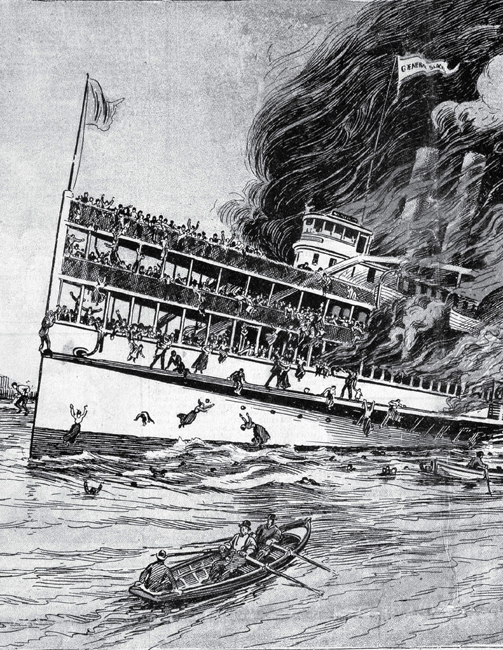

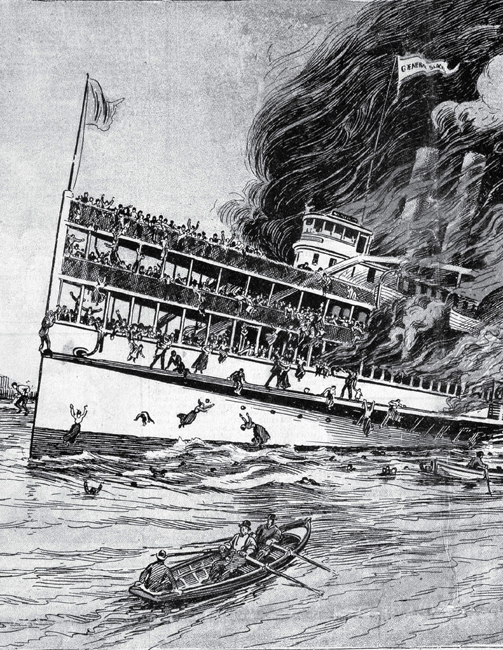

An artist’s depiction of the ship in flames. [Mariners’ Museum]

Several people tried to launch the ship’s six life rafts, each of which would hold twenty passengers. “Unclasping my knife,” Nicholas Balser said, “I slashed at the fastenings of the life rafts nearby. But they were secured by wire instead of rope.” The rafts had been wired tightly to the deck so they wouldn’t rattle during rough water or storms.

Few passengers could swim, but they leaped overboard anyway. “My wife and I stood together by the rail until we saw that the upper deck was about to fall upon us,” said the Reverend Haas. “We saw nothing of our little girl, who had been playing with other children. My sister stood near us. None of us could swim, but when we realized that it meant certain death to remain longer on the steamer we all jumped overboard together.”

The scene in the water, John Tischner remembered, was deadly, too. “Twenty would jump at once, and right on top of them twenty more would jump. Then there would be a skirmish of grabbing at heads and arms, and the fellows that could swim would be pulled down and had to fight their way up.”

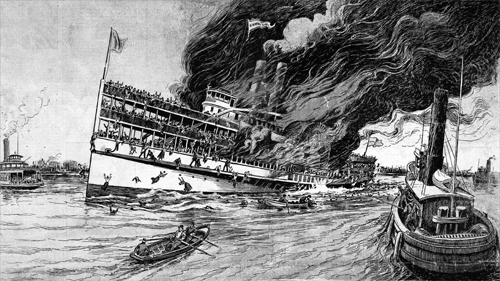

The newspapers were filled with stories about the General Slocum tragedy. [The World, June 15, 1904]

The charred remains of the General Slocum. [LOC, USZ62-138405]

Ten-year-old Walter Mueller barely avoided drowning. “After papa tied the life preserver around me I jumped into the water. The life preserver was of no use for it broke right off me, and I thought I was going to drown. I grabbed a man’s neck and went under the water. When I came up again, I seized a woman by the hair and she scratched my face.” Walter let go, and as he was sinking, a man in a boat grabbed him.

Tugs, ferries, fireboats, and police boats chased the Slocum and pulled people from the river. Mothers and fathers flung their daughters and sons into the water, hoping they would be rescued or at least be spared from burning to death. One tugboat captain braved the flames long enough for parents to drop their children onto the tug’s deck. But to avoid catching fire, the tugboat had to pull away. The tug’s captain said he would never forget the pleas and screams of the people he left behind.

Just before the Slocum reached North Brother Island, the bulkheads—a ship’s walls—supporting the upper deck collapsed, spilling passengers into the flames below. The pilots tried to swing the boat around so its stern would be near shore. But the ship suddenly ran aground on submerged rocks. The bow, completely in flames, was just 20 feet from land, but the stern, where the surviving passengers were, was in deep water 270 feet from shore.

There was a last desperate attempt to save lives. Charles Swartz, Jr., an 18-year-old passenger, climbed into a boat and helped its owner rescue 22 people. “I went overboard whenever I could,” he recalled, “and swam up to people and helped them in the boat.” A Riverside Hospital switchboard operator swam out to the ship a dozen times, saving as many people as possible before she collapsed, exhausted.

Some passengers saved themselves in grisly ways. “I didn’t have no life preserver at all,” said ten-year-old Henry Ferneissen. “I went down twice and I swallowed a whole lot of water, but pretty soon I caught hold of a dead woman and then somebody grabbed me with a hook. If it hadn’t been for that dead woman I’d been drowned sure.”

One hour after embarking, the General Slocum was a smoldering ruin and most of its thirteen hundred passengers were dead. One survivor said, “To my dying day I’ll never forget the scene. Around me were scores of bodies, most of them charred and burned.”

A view of the paddle wheel and other debris on the burned-out steamship. [LOC, USZ62-138402]

Rescue workers fished hundreds of corpses from the water and pulled hundreds more from the wreckage. For several days afterward, people found corpses of men, women, and children washed up onshore or floating in the river. Some victims were never found. No one knows exactly how many of General Slocum’s passengers died. The official estimate is 1,021. All of the Slocum’s crew survived.

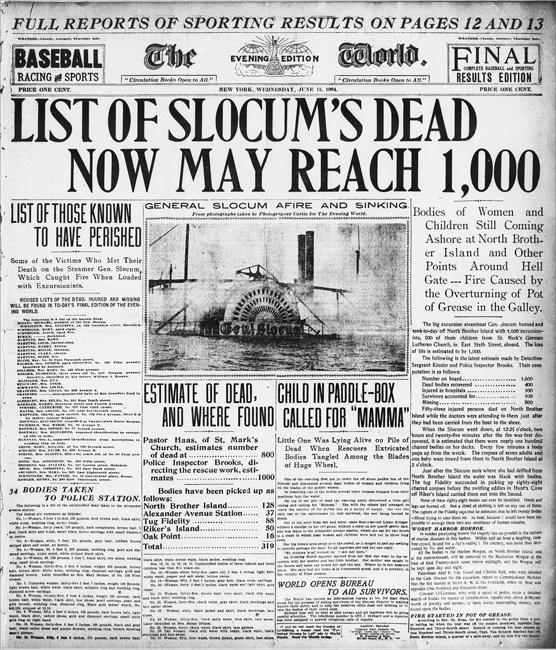

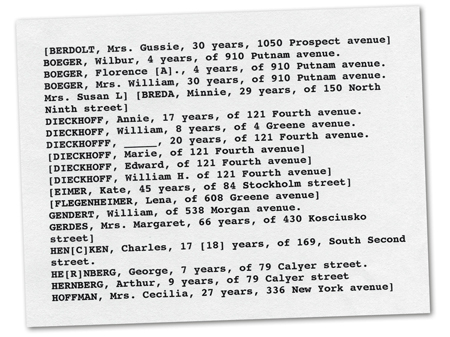

Partial list of the dead. [Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 15, 1904]

A grand jury later indicted two government steamship inspectors, four Knickerbocker Steamship Company executives, and Captain Van Schaick. Only the captain was convicted of negligent homicide. The judge sentenced him to ten years in Sing Sing, an upstate New York prison. Meanwhile, federal officials made steamboat safety regulations more stringent and reformed the U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service.

The General Slocum tragedy is the worst peacetime maritime accident in American history. It was New York’s deadliest disaster until the twenty-first century.

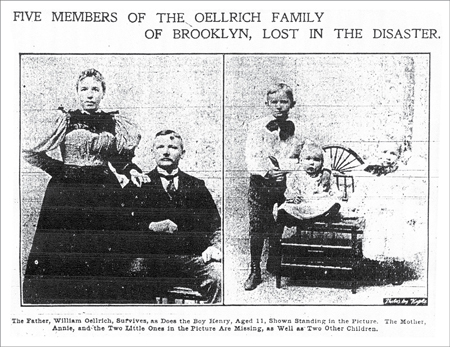

A family that lost five of its members to the fire. [Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 15, 1904]