6

AMERICA’S LAST GREAT URBAN FIRE

SAN FRANCISCO, 1906

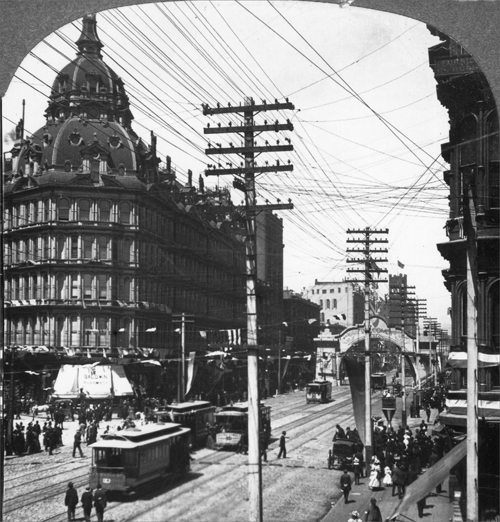

A half century after the 1849 California Gold Rush, San Francisco had become the Crown Jewel of the Pacific. It was the West Coast’s largest city and, according to the 1900 census, the ninth-largest city in the United States. But three horrific days in April 1906 left San Francisco in ruins and its future in doubt.

At 5:12 A.M. on Wednesday, April 18, one of the strongest earthquakes ever recorded rumbled along the West Coast from Southern California north to Oregon and as far inland as Nevada. San Francisco was only two miles from the quake’s epicenter. In just 48 seconds, the quake toppled hundreds of buildings, felled utility poles, broke gas pipes, and ruptured storage tanks full of oil, gasoline, and kerosene. It also snapped most of the pipes supplying the city’s water from outlying reservoirs.

Market Street, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, before the fire. [LOC, USZ62-98494]

The San Francisco Fire Department’s seven hundred firefighters quickly turned out. At first, there were no fires visible, so they rescued people trapped in collapsed buildings. “At No. 313 Sixth St., the place was completely wrecked and the bare foot of a child could be seen in a pile of debris,” Captain C. J. Cullen of Engine Company No. 6 later wrote in his report. “We cut our way into the premises with axes and shortly afterwards rescued three little children and five adults.” But soon the firefighters had to turn their attention to numerous fires, started by downed electrical wires and stoves in restaurants and homes, that had begun to flare up all across San Francisco.

Engine 15 several years before the 1906 fire. [LOC, HABS CAL,38-SANFRA,72--3]

Residents amid the earthquake’s destruction, watching the spreading fire. [LOC, G4085-0201]

South of Market Street, reporter James Hopper saw fire “swirling up the narrow way with a sound that was almost like a scream.” At Third and Market, “the tallest skyscraper in the city was glowing like a phosphorescent worm,” Hopper wrote, describing the 15-story Call Building, and “fire poured out of the thousand windows.”

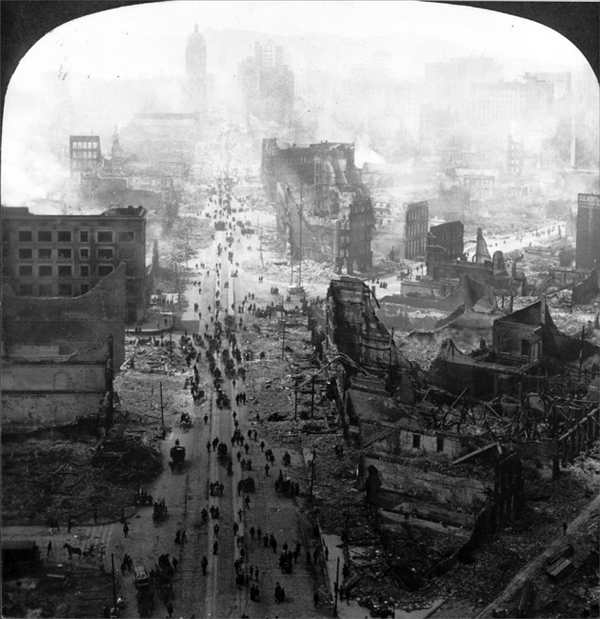

In just a few hours after the earthquake, San Francisco was in flames. [LOC, USZ62-44926]

By evening, “the lower portion of Market Street, Chinatown, and Nob Hill was one seething furnace,” observed another reporter. “Thousands of angry flames shot high into the sky, and the cracking timbers, the falling buildings, and the terrific roar of the fire sounded like a dozen cyclones.”

A piano company ablaze. [Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California, Berkeley]

Firefighters tapped every possible source of water, including the sewers. Resorting to colonial-era firefighting tactics, Engine Company No. 26 formed a bucket brigade from a well to a burning building. Other firemen tapped old underground storage tanks, called cisterns, each holding between ten thousand and thirty thousand gallons of water. Sixty of them had been built a half century earlier, after a big fire in 1851 had leveled the young city.

Soldiers patrol the streets to prevent looting. The Call Building, then the tallest building west of the Mississippi River, looms in the background. [LOC, USZ62-96789]

At 17th and Howard streets, reported Captain Cullen, “there being considerable water in a large hole in the middle of the street owing to a broken main, with stones and sand we dammed the water that was running to waste and put our Engine to work after stretching hose as far as Capp St. near 16th St. Here we had a very hard fight as the wind was blowing the intense heat of the fire in our direction. Soon it became unbearable … but after fighting every inch of the ground we succeeded in getting it under control at 20th St.”

One reliable water source was San Francisco Bay. “We laid a line from the Fire Boat to Broadway and Mason streets, a distance of fourteen blocks, taking about 4,000 feet of hose,” reported Battalion Chief John McClusky. “The Fire Boat and three engines [were] all pumping on this single line, [and] with this one stream we worked vainly to prevent the fire from crossing the north side of Broadway.”

The firefighters made one heroic stand after another. “Many of them dropped utterly exhausted at their post of duty, which was quickly taken up by one of their comrades,” a writer observed. “They stood in the smoke of the roaring furnaces to fight the flames and cases are on record where police officers and volunteer firemen had to continually apply a stream of water on the regular firemen on duty in order to keep them from being burned or scorched.”

The firefighters worked around the clock, snatching bits of sleep whenever they could. “When opportunity afforded,” wrote Captain George F. Brown of Engine Company No. 2, his men “got an hour or two of rest in the doorways and in the streets alongside their apparatus, and the little they had to eat during these fifty hours of continuous service was given to them by kind-hearted people.”

The crowds in the streets, said one observer, resembled war refugees: “thousands of families of women and little children dragged themselves from place to place in front of the flames, lying without shelter in vacant lots, exposed to fog and chilling rain.”

The cold drizzle didn’t slow the fire, so the firefighters created firebreaks. Dennis Sullivan, the city’s chief fire engineer for 13 years, had been an expert on the use of explosives. But he and firefighter James O’Neil had been fatally injured in the earthquake. The men setting the explosives learned by trial and error. “It was an earth-racked night of terror,” recalled one resident. “We watched the leaping and hissing flames in the city below us, and heard the crashing of buildings.… By dynamiting buildings, the firemen hoped to check the conflagration. Much dynamite was used, many buildings blown to atoms, but all was in vain.”

Firemen spraying a heavily damaged building. [LOC, USZ62-113371]

One explosion made the fire worse. The flames were nearly conquered, some observers believed, until the firefighters dynamited a building on Van Ness Avenue. The explosion spread the fire, which then destroyed another fifty blocks.

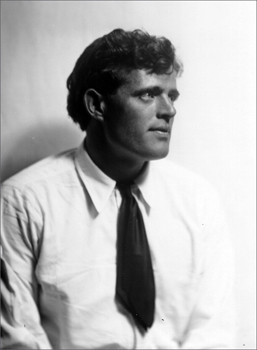

Hours later, firebreaks did work. “The great stand of the fire-fighters was made Thursday night on Van Ness Avenue,” wrote novelist Jack London, who came from his home across the bay to see the fire. “Had they failed here, the comparatively few remaining houses of the city would have been swept. Here were the magnificent residences of the second generation of San Francisco nabobs, and these, in a solid zone, were dynamited down across the path of the fire. Here and there the flames leaped the zone, but these fires were beaten out, principally by the use of wet blankets and rugs.”

A photograph of Market Street that appears to have been taken from an overhead balloon. [LOC, USZ62-49317]

In three days, the fire destroyed 28,188 buildings on 490 city blocks. It covered 2,600 acres, 600 acres more than the Great Chicago Fire. The disaster left half of the city’s 410,000 residents homeless. “Not in history has a modern imperial city been so completely destroyed,” wrote London. “San Francisco is gone.”

Jack London, an author best known for his novel The Call of the Wild, wrote a firsthand account of the fire. [LOC, G399-0200]

Civic leaders tried to downplay the tragedy, historians believe, because they didn’t want people to think San Francisco was an unsafe place to live or work. They reported a death toll of 376 people. Years later, researchers discovered over three thousand had died in the earthquake and fire.

Devastation. [LOC, USZ62-47147]

San Francisco quickly rebuilt homes and businesses. Workmen repaired the broken pipes and 54 of the old cisterns. Then they added 85 cisterns, each holding 75,000 gallons of water. In 1954, the city constructed Summit Reservoir, which holds fourteen million gallons of water at Twin Peaks, the city’s second-highest point. If that runs out, two pumping stations can refill the reservoir by drawing water from the bay. Even with these precautions, San Francisco never quite regained all of its luster. By 1920, Los Angeles had become the West Coast’s largest city.

The San Francisco fire was America’s last “great” city fire. More effective firefighting equipment, better-trained firefighters, reliable water supplies, strong fire codes, and modern building materials have all made large-scale fires less likely.

A weary-looking man trudging up one of San Francisco’s steep hills. [LOC, USZ62-47591]