Back home, I went straight to the shed to tell Eric my idea. He was surrounded by grow bags, big plant pots, a few collapsible chairs, a sun lounger, an old-fashioned electric kettle and some cushions. But, most of all, by memories. Memories seemed to rush out of that shed on the breeze. I couldn’t tell you what they were memories of exactly. A feeling of remembering blew all around me, then seemed to vanish, like a song on the radio of a passing car. I felt I’d lost some big, shiny memory, just like I’d lost my hand.

Then I saw exactly what I was looking for, and I forgot all about my feelings. Sticking up from behind the pile of cardboard boxes – like a meerkat looking out for trouble – were the handles of my scooter. I’d forgotten I even had a scooter. As soon as I saw it, a memory was triggered – the scooter was something to do with my accident.

I went over to pick it up and, as I touched it, little flashes came back to me. As if the scooter was a USB stick, and I’d stored bits of memory in it.

I let the memory go.

I was far too busy to think about stuff like that now.

I hoisted the scooter out from behind the boxes. Apparently it had come out of the accident without a scratch. Mum must have put it in the shed until I was ready to ride it again. It’s got a telescopic steering column, so you can make it as tall or as small as you like.

You can, for instance, make it exactly the same size as Eric’s leg. Which is what I did.

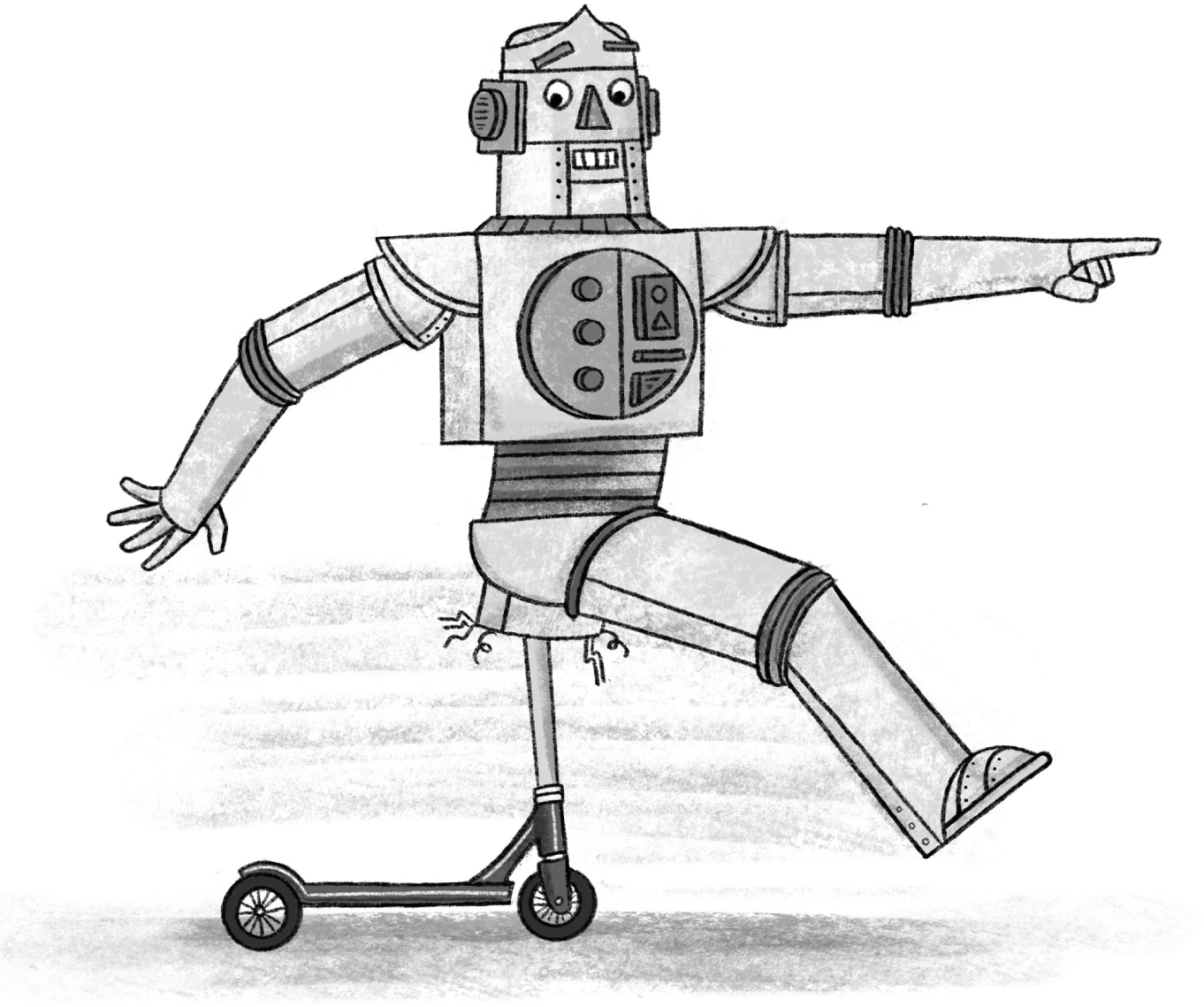

‘Eric,’ I said, ‘what if you had a scooter for a leg? One leg could be the scooter, and the other leg could scoot. I’ll show you.’

I stepped on to the scooter to show him how it worked.

I AM YOUR OBEDIENT SERVANT.

‘Good. Follow me.’

Out in the yard, I wedged the handlebars into the slot at the bottom of his torso where his left leg went, turned it round until it I couldn’t any more, and tightened all the screws. The running board was also extendable. I jiggled it round until it was the same size as Eric’s foot. It had two wee whizz wheels, one on each end.

‘Right, Eric. Give it a whirl.’

Eric tried a step. The scooter shot forward from under him. He should have fallen backwards, but his other leg came down just in time to stop him. He tried it again.

And again.

And again.

IF YOU WILL PERMIT ME . . .

‘Yeah, go ahead. Keep practising.’

It was working! The sun slithered over Eric’s metal panels as he moved. He was upright and mobile. When he wobbled into the gate, it swung open.

‘Eric, don’t go out.’

I AM YOUR OBEDIENT SERVANT, said Eric, going out.

‘Do you actually even know what obedient means?’

I’M SORRY. I CAN’T ANSWER THAT QUESTION.

He rumbled over the concrete patio of the yard. He wobbled through the gate. He scooted – proper scooted – down the alley.

‘Eric! Don’t go far!’

At the very end of the alley, he spun round and scooted back towards me; then he stopped and spun round again. He spread his arms out and aeroplaned back down the alley. His steel fingers struck sparks all along the backyard walls.

The sparks made other memories flash in my head – I remembered plunging down underpasses on my scooter on bright sunny days. Scooting along walkways.

I KNOW HUNDREDS OF JOKES.

He whooped, in a way that seemed to say, ‘I’m really chuffing chuffed with myself.’ He shot to the far end of the alley, turned left, and then . . .

He disappeared.

‘No! Eric! Come back!’

I tore after him. Out of the alley, on to Stealth Street. When I caught up with him, he was holding on to a lamp post with one hand, spinning himself round it. For a machine that had no emotions, he was doing a brilliant job of looking really happy. He sounded like a hundred dustbins having a party.

‘Eric, slow down! You’re going to fall!’

I AM YOUR OBEDIENT SERVANT.

Then he clattered on to the pavement.

‘Eric?’ I cried. ‘What’s happening? Are you dead?’

No. Eric’s a machine. Not a person. He’d never been alive, so he couldn’t be dead. Machines are not like people. If a machine stops working, you can fix it. Like I said, with machines, there is always a way to fix them. You just need to stay calm and think.

What I thought was . . . batteries. What if Eric just needed recharging?

I searched his body for some kind of socket. There were three metal spikes sticking out of his neck like the prongs that stick out of the bottom of an old-fashioned kettle when you pull the electric cord out. I knew because I’d just seen a kettle like that in the shed.

I dashed back to the shed, grabbed the kettle lead, and returned quickly to Eric. It slotted snugly over his spikes.

Great! All I had to do was plug him into one of the DustUrchin recharging points. There was one on every lamp post.

Except the lead was only about half a metre long.

And the nearest lamp post was on the other side of the road. How was I going to move half a ton of steel across the road? Easy! Extension lead. Great. There was one in the shed. I ran and got it. Plugged him in. All I needed now was for the road to stay completely deserted for the next . . . how long?

How long was it going to take? It takes about half an hour to charge my phone, and Eric is about a million times bigger. What if it took half a million hours? I was panicking that, any minute now, the empty pavements would be full of kids coming home from school, and everyone would know about Eric.

I crouched over his body, willing him to recharge more quickly. I was thinking that even if he just got to three per cent I could probably move him back to the shed before anyone saw him.

All the time Eric was lying alone on the pavement, my heart was in my mouth. Luckily there was no one around. Everyone was at school or at work.

After a few minutes, there was a faint tinkling. Well, not tinkling exactly; more of a rattle with a squeak thrown in. The sort of noise you hear if there’s a coin rolling around in the glove compartment of your car. Then Eric’s eyes started to glow slightly. Eric was charging up.

Then I heard a faint whirring sound overhead. The lamp post’s CCTV camera was focusing in on us. If you’re going to keep a secret on the Skyways Estate, you have to hide it from lamp posts as well as people.

Then people turned up.

A driverless bus stopped just across the road, and people got out. Lots of people. Kids. In uniform. The uniform of Skyways High (‘Aiming Higher’). My school.

Someone spotted me. ‘Look! It’s Alfie Miles!’

They all flocked across the road towards me. As they got closer, names popped into my head one after the other, like something was being uploaded into my brain.

Dr Shilling had given us special lessons on how to cope when your old friends meet your new limb.

‘Some of them will be freaked out,’ she’d said. ‘They might be rude or cruel. Mostly that just means they’re scared or uncomfortable. Which means you’re in control. It’s up to you to put them at ease. Tell them a joke. For instance, say, “Do you need a hand?” Then take your hand off and offer it to them. Works every time. Ha ha.’

Freaking people out seemed like the best tactic for me at that moment. At least it distracted them from the massive illegal robot on the pavement.

As they got nearer, I could hear them talking.

‘I thought Alfie Miles was killed in a tragic accident?’

‘Not killed, just hideously mangled.’

I lifted my Osprey hand. For one second, it was like I’d pressed the mute button on life. Everyone stared. The next second, it was noisier than ever. They were yelling and squashing and clambering over each other to try to get a better view.

‘Is that yours?’

‘Is that real?’

‘Does it come off?’

Literally no one was looking at Eric. Only at me. In fact, some people were standing on him so that they could see me better.

When everyone is staring at you, you’ve got options.

You can run and hide.

You can curl up like a hedgehog.

Or you can give them something to stare at.

So, I wrenched my own hand off, and I held it out for them to see. First, they screamed and backed off. Then they gasped and leaned forward.

‘Can I hold it?’

That was a girl I used to sit next to in Padre Pio Primary. She had the reddest hair on the planet, but I couldn’t remember her name. And she couldn’t wait for a reply. She just grabbed my hand and held it away from her like she was holding a tarantula. She prodded it with her fingernail.

‘Can you feel that?’

‘No. Of course not. It’s not even connected to my arm.’

‘If I bend the finger back, will it hurt?’ She bent the middle finger backwards until the tip touched the wrist. ‘Ohmygoditgoesrightback! What’s his name? Has he got a name?’

It was really rattling me now that I couldn’t remember this girl’s name, so I said, ‘Tell him your name, and maybe he’ll tell you his.’

‘You mean he can talk? Like if you talk to the hand, the hand talks back! That’s so amusing. And it’s a he. Is it a he?’

‘Well, I’m a boy, so, yeah, I’m going to have boy hands.’

‘Hello, Hand. My name’s Maria-Jaoa. What’s yours?’

Maria-Jaoa! Now I remembered. She was always saying, ‘Ohmygodsocute!’ about various people and things.

I said, ‘He doesn’t have a name. Why should he have a name? Does your hand have a name?’

When she let go of it, the hand opened up like a flower.

‘Ohmygodsocute! I’m going to call him Lefty.’

I did try pointing out that it was my right hand, but she said that was the joke. I could have tried pointing out that it really wasn’t down to her to think of names for parts of me, but it was already too late. Everyone loved the name Lefty.

At the Limb Lab, they told us that giving a name to your new state-of-the-art limb made it easier for people to relate to it. But they never explained that it would be THIS easy. Within about ten seconds of being given the name, Lefty had a crowd of admirers. If you check now, you’ll see he’s got his own Facebook group: ‘Friends of Lefty’. If I call into Skyways High now, more people know Lefty’s name than know mine. I’m not Alfie Miles there; I’m just Lefty’s human appendage.

Not going to lie – I actually was having a good time at that point. I forgot that Eric was in danger. I gave a kind of demonstration on How Lefty Works. I showed them how you could press the fingers back into the hand or lock them into different positions: hanger, shovel, fist, palm, pointer.

I didn’t say, ‘The hand doesn’t really need me to move its fingers. It could do all these things with a thought. If I could just think the right thought.’

Instead I said, ‘So who wants to shake hands with Lefty?’

Oh, they loved that. They formed a queue.

Most of them weren’t satisfied with just a handshake. Most people wanted a selfie.

When I got bored, I pulled the middle finger clean off. A beam of light shot out from the inbuilt torch, and I said, ‘Sorry, sorry – that’s the laser! Better get back, everyone!’

And everyone backed off, laughing.

Then, behind my back, Eric began to shake. He was almost recharged. He was trying to stand up. I had to get rid of them.

Easy.

I put my hand down on the floor and said, ‘Everyone! Watch Lefty!’ So even I was calling my hand Lefty now.

I ran up to the corner of Stealth Street and turned my phone on. I couldn’t actually see Lefty from there, but I could hear the pretend screams and laughs as he began to spider crawl along the pavement towards me.

They followed him all the way to me. They all said it was the coolest thing ever and asked me when I was going to come back to school.

‘Soon,’ I said.

‘We weren’t talking to you,’ said one of the girls. ‘We were talking to Lefty!’

Everyone laughed and went home.

Maria-Jaoa lived on Spitfire Street so she walked back with me, which was awkward. Because we had to pass Eric.

‘Oh my God,’ she said. ‘It’s that killer robot. The one that’s been rampaging around killing kids.’ She was one of those people who thought the news always understated things so you had to exaggerate to get the truth.

‘Oh no,’ I assured her. ‘That’s not a robot. That’s a project.’

‘What kind of project?’

‘From the Limb Lab school. We have to make stuff, so I’m making a suit of armour.’

‘It’s got a scooter instead of a leg.’

I said, ‘Yeah. So?’ and looked meaningfully at Lefty.

‘Oh.’ Maria-Jaoa blushed. ‘I get it. It’s a suit of armour for someone with no leg. Awkward. Sorry. I bet loads of knights only had one leg. I bet the best ones only had one leg because they lost the other one in battle.’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘Well, see you soon.’

‘See you, Alfie. See you, Lefty.’

I let Lefty wave to her.

A few minutes later, Eric was upright so I unplugged him, and we scooted back home. As soon as we were back in the shed, he said:

WATER LEVEL IS LOW.

‘You need water?’

He opened his mouth really wide and tipped his head back.

I rushed into the house, got a jug of water and poured it down his throat. Then I started to worry. Surely water and electricity are a fatal combination? Steam began to come out of Eric’s ears. There was a banging in his chest. I backed away to the shed door, ready to dive for cover if he exploded. Then a panel in his chest popped open. He reached inside and pulled out . . . a camping kettle.

FOUR O’CLOCK, he said. TIME FOR TEA.

He held the kettle on his open hand, and his palm began to heat up. Soon the kettle was singing like a bird. With his other hand, he pulled out of his chest a china teapot decorated with flowers, two china cups and saucers, and a milk jug.

LEAVE TO BREW FOR FIVE MINUTES.

Obviously there was no tea in the pot and no milk in the jug.

SHALL I BE MOTHER?

He poured some hot water into the tea cups. I sipped it politely and chatted to him about the day. He kept nodding his head. Maybe making tea was his way of saying thanks for fixing his leg.

Not going to lie, when I decided to fix up a massive illegal robot, I thought I might need to find lasers or weaponry for him. Instead, I ended up promising to get him some fresh milk and tea and sugar from the Co-op.

When Mum came home that night, she rushed right at me, saying, ‘Are you all right? Are you all right?’

‘Yeah. Why?’

‘I heard that a bunch of Skyways High kids had you surrounded at the bus stop. Were they bullying you?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘To be honest,’ I said, ‘I sort of gave them the impression that my new hand had laser capabilities.’

She laughed, and I said, ‘Nice cup of tea?’

She said, ‘Ta.’

A few minutes later, Mum was in the kitchen, wondering why her tea wasn’t ready. ‘I only wanted a mug of tea, Alfie – a mug with a tea bag and some hot water in it. Not a dress rehearsal for the queen’s garden party.’

I looked down at the tray. It’s true; we usually made tea in a mug with a tea bag. Maybe hanging out with Eric had made me a bit more – I don’t know – formal. I’d made tea in the teapot and put it on a tray with proper cups and saucers, napkins, a china sugar bowl and milk in a jug. The sugar bowl was probably a bit much, especially as neither of us take sugar.

‘Sorry. It’s ready now.’

‘I’m only teasing. I think it’s lovely.’

‘You know,’ I said, ‘the kids from school were really nice. They even gave my hand a name. Lefty.’

‘But it’s a right hand.’

‘I know. That’s the joke.’

‘Oh, I see.’ She laughed again. ‘Maybe that will help. Giving it a name. If you think of your hand as a pet rather than a hand, maybe that will help give it some, you know, life. Like I do with Ollie.’

Ollie is what she calls the DustUrchin. Ollie the Omnivore. To demonstrate, she dropped a pinch of sugar on the lino and said, ‘Come on, Ollie. Come on, little fella . . .’

The Dust Urchin came scuttling over and sucked up the sugar.

‘See? The more you talk to a thing, the more alive it gets. You have to put some of yourself in there.’

‘The kids in school,’ I said, ‘were actually nicer than the kids in the Limb Lab. Maybe I should go back to school instead of the Limb Lab.’

‘Definitely,’ said Mum. ‘The moment you bring Lefty to life. The day you make his fingers move, you can go back to school and all your old friends. That’s what we agreed.’

‘Right.’

‘All you need is a little imagination.’