5 Symbolist opera: trials, triumphs, tributaries

[Winter, 1914:] The coal merchant had a pretty wife who was also an excellent musician, and she gave [ Debussy] some [coal] in return for an inscription on her copy of Pelléas . . .

GABRIEL ASTRUC (1929)

The idea that so aesthetically rarefied a work as Pelléas might have been the occasion of a request (in wartime, too) for a quick autograph from Debussy by a local tradesman’s wife with a passionate interest in music reminds us just how widely known and well loved the opera had become in France after the polemics of the work’s initial reception had died down. It further helps us to understand why nearly 30 years later, after a fairly dismal decade for the opera during the 1930s, the wartime performances given in 1942 at the Opéra-Comique under Roger Désormière were to be such an important manifestation of national identity and ‘cultural resistance’ during the Nazi Occupation, and also how they managed to exert such a powerful fascination at the collective psychological level, as well as bringing about a certain reinvigoration of the work itself as a musical and dramatic entity (Nichols and Langham Smith 1989 , 156–9).

This in turn provides a context – to an extent backward looking and more than a little nostalgic, yet honest and deeply felt – for the renewed passion with which the piece now came to be viewed, both in itself and as an embodiment of French taste and identity; and also for the sense of shock that greeted the groundbreaking, in every sense iconoclastic postwar production by Valentine Hugo, also given at the ‘temple’ of the Opéra-Comique, in 1947. The décor of Hugo’s production, in line with the radicalism of her general concept of the work, went very much further than did the thoughtfully simplified, slightly modernized designs of Valdo-Barbey for the 1930 revival (Valdo-Barbey 1926 ). That the 1947 staging was felt to be so shocking can be easily documented, but is made even more obvious by the almost immediate return to a ‘revivalist’ mode of production for the 1952 staging, which deliberately aimed at what would probably be thought of today as a historical reconstruction in the realist French Gothic spirit of the original 1902 stage sets by Jusseaume and Ronsin (Nichols and Langham Smith, 1989 , 159–61; see illustrations in Lesure 1980 , 85–91) .

But the mould had been broken. The task of preserving an original production at all costs as a would-be permanent link with the past, as a kind of talisman even, could now be seen and understood more clearly for what it was – a fantasy that carried with it a strong dose of fetishism and which, beneath a veil of fidelity, in fact showed little confidence in the opera’s inner strength and complexity as a vehicle for new interpretative work. Moreover, there are signs that by 1914 Debussy himself may have been growing tired of the constraining literalism of the 1902 sets and longing for something new (Nichols and Langham Smith 1989 , 154), even if his expressive vision for the music – both in his imagination and as realized through Messager’s expert conducting at the premiere – seems to have remained fairly consistent over the years. The 1947 Hugo production (seen also at Covent Garden in 1949) had done its work, however. Not only was the way now open for other more experimental productions to take place across Europe, even little by little in France (though significantly not in Paris, at least not until the 1970s); but the first steps had been taken, in the realm of staging and design, towards the more thorough-going musical and interpretative revaluation of the work that was to occur under the impetus of Pierre Boulez in 1969 (at Covent Garden) and again in 1992 (in the staging for Welsh National Opera, produced by the charismatic German theatre director Peter Stein).

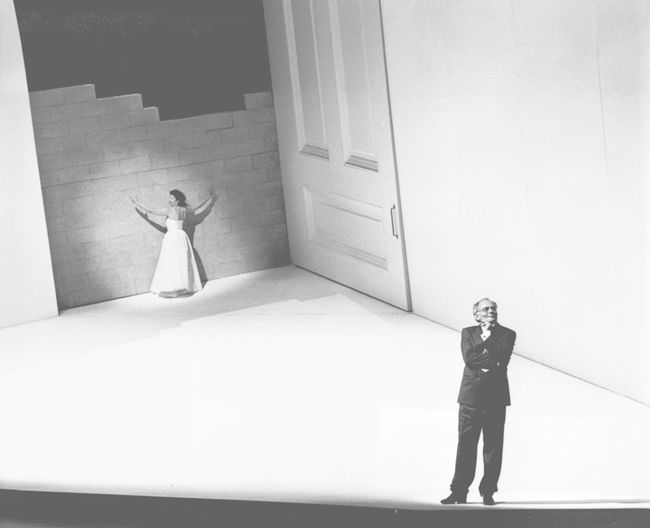

Figure 5.1 Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande , directed by Peter Sellars with set designs by George Tsypin (Netherlands Opera, 1993). Left to right : Arkel (Robert Lloyd), Golaud (Willard White) and Mélisande (Elise Ross). Photo: Deen van Meer.

The exploration of new, more or less radical styles of operatic production was a widespread postwar phenomenon, the most famous – and most obviously institutionalized – instance of which was the remaking of the Bayreuth tradition during the 1950s and 1960s. Partly because of the great scale of the undertaking and the wide diffusion of knowledge about Bayreuth, partly because of the simple fact of Wieland Wagner’s uniquely powerful vision and the sheer energy and practical genius with which he set about realizing it, this radical shift in stagecraft – which itself owed much to the physical simplicity and extreme concentration on lighting effects that had emerged from symbolist thinking about the nature and workings of the theatre, as well as to the seminal ideas of such prewar figures as Adolphe Appia and Gordon Craig and their disciples in Germany – quickly set up what was to become something close to a distinctive postwar ideal: a new anti-realist orthodoxy with a strongly abstract and symbolic bias. The overriding need for a fearlessly radical intepretative approach to production had been the difficult, yet in the end revelatory, conclusion to which Wieland Wagner gradually came during his months of intensive study and reflexion in the immediate aftermath of 1945 (Spotts 1994 , 208–11) .

Symbolist opera, during its brief but intensive historical moment in the years preceding the First World War, had also reacted against the prevailing bourgeois and conventional view of theatre and musical drama. It stood against what it saw as the false grandiloquence of grand opera and the romantic melodrama, the exaggeration and sentimentality of verismo , and the banality of naturalism and the realist theatre. (To Debussy’s annoyance the star of Gustave Charpentier’s hugely popular Louise was indisputably in the ascendant following its premiere in 1900; even during the Pelléas rehearsals in early 1902, Mary Garden was still busy singing Charpentier’s title role.) Symbolist opera took its cue from Wagner, as poets and writers and artists had done, and as we can conveniently observe in the socio-cultural phenomenon ‘wagnérisme’ and the brief existence of the Parisian Revue wagnérienne (1885–8). Yet it was a profoundly altered version of the Wagnerian ideal which was its point of departure – the transformative product (so to speak) of the symbolists’ reading of Wagner, allied with a radical compositional rethinking of how this kind of drama could best be embodied musically .

Above all, there was a strong antipathy and resistance to external realism, especially in its most literalistic guise. Human content, so the argument went, could be conveyed more directly and authentically, with greater subtlety and complexity, by ignoring the lure of realism and illusionism and concentrating instead on finding a language of atmosphere and evocation (this was one of the key tenets of symbolism as it was manifested in every medium and genre). The poetic descent of the movement took Baudelaire and Mallarmé as its patrilineal creators; but the transference of symbolist ideas on to the stage in live theatre became an issue of real aesthetic and cultural importance only with the rise to public prominence in Paris of Maurice Maeterlinck around 1890 (McGuinness 2000 ).

Stories and scenarios: Maeterlinck and beyond

Both Maeterlinck’s dramatic experimentation and the various operatic responses to it involved a radical rethinking of what a theatrical scenario could consist of, and what kinds of psychological and expressive results might then be drawn from it. Maeterlinck’s exploration of the possibilities of static theatre, his extreme reduction of external action, his exploitation of silence not just as a dramatic effect but as a surrounding medium for language and gesture, and his concentration on evocation and atmosphere, as well as an idiosyncratic approach to stage rhetoric (which in most respects is in fact anti-rhetorical), all pointed in one general direction: the creation of a sense of mystery and depth.

It is noteworthy that Debussy should first have expressed his need for a novel and ‘original’ operatic subject in terms not of plot or action but of dramatic atmosphere, and that he seems already to have heard his musical sound-world inwardly before finding a subject that was appropriate to it. All this is most strikingly expressed – as early as 1889–90 – in the conversations he had with his former teacher Ernest Guiraud. Having returned from the revelatory journeys to Bayreuth he made in 1888 and 1889 when he saw Wagner’s Parsifal , Die Meistersinger and Tristan , Debussy’s ideas were now heading in an entirely new and anti-Wagnerian direction. He described his search for

[a] kind of poet . . . who only hints at what is to be said. The ideal would be two associated dreams [i.e. that of the poet and that of the musician]. No place, nor time. No big scene. No compulsion on the musician, who must complete and give body to the work of the poet . . . My idea is of a short libretto with mobile scenes . . . No discussion or arguments between the characters, whom I see at the mercy of life or destiny.

(Lockspeiser 1978 , 205, translating the recollections of Maurice Emmanuel)

That his practical needs – as well as his dreams – were answered by the appearance of Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande both in book form (Maeterlinck 1892 ) and in the theatre (at the Bouffes Parisiens in 1893, directed by Lugné-Poë) is the key historical conjunction through which symbolist opera was able to come into being as it did (though prior to this he seems briefly to have considered setting Maeterlinck’s earlier play La Princesse Maleine of 1889). Debussy attended the single staged performance given on 17 May 1893 by the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre, having previously bought himself a copy of the printed text (Lesure 2003 , 140–41). From this point on he devoted, with significant intervals, fully ten years of his life to the creation of the opera he had already intuited, as if from a mysterious distance, inside his head. The vicissitudes of the ‘Pelléas years’ are a vital and enthralling story in their own right (Grayson 1986 ; Lesure 1991 ). And after the long years spent imagining the action as a totality while working on the score, Debussy spent hundreds of hours in rehearsal at the Opéra-Comique during the weeks and months leading up to the now-legendary dress rehearsal, followed by the premiere on 30 April 1902 (chronology, based on the unpublished diary of Henri Büsser and other sources, in Lesure 2003 , 219–22). At this point the man whose aesthetic ideal was one of fantasy and infinitely extensible imagination was finally brought face to face with all the mundane practicalities of the cumbersome theatrical machine. Yet although, as we can read in his correspondence, he often expressed anger and frustration at all the various practical difficulties associated with the theatre, he seems never to have lost faith in the immediacy and power of the experience that could be conveyed through the medium of dramatic music, rightly understood and entered into.

Maeterlinck’s libretto Ariane et Barbe-Bleue , written in the first place as a vehicle for his mistress, the soprano Georgette Leblanc (whom Debussy had refused to cast as the first Mélisande), might have been set to music by Grieg. But it was Paul Dukas who, around 1899–1900, began work intensively on his setting of the text, and the finished opera was given at the Opéra-Comique on 10 May 1907, with Leblanc in the title role and with set designs again by Jusseaume. This opera, too, was a sustained labour of love by a relatively young and idealistic composer, just as Pelléas had been. Debussy and Dukas were close and artistically intimate friends during these years, who shared many of their views about literature and the arts; and although little direct evidence survives, there can be no doubt that they would have discussed Maeterlinck and his ideas as well as those of such key poetic figures as Baudelaire and Mallarmé (Lesure 2003 , 94). Dukas, moreover, was one of the very few privileged interlocutors with whom Debussy shared the whole story, the trials and tribulations as well as the triumphs, of the ten-year gestation of Pelléas .

The fact that later generations have treated Ariane so neglectfully by comparison with Pelléas should not blind us to Dukas’s importance within the historical moment of symbolist opera and its immediate aftermath. There may or may not be good reasons why Ariane is often thought to be theatrically unviable – the extreme prominence (and vocal demands) of the role of Ariane, for instance; the extreme paucity of that of Bluebeard; and the particular kind of monumental stasis which the opera as a whole is seen as embodying (not unlike the equally controversial case of Messiaen’s Saint-François d’Assise of 1983). But it made a great impact in the early years of its life and was staged internationally more quickly than Pelléas was. Within six years of the premiere, it had been seen and heard at Vienna (1908), Brussels (1909), New York and Milan (1911), Buenos Aires (1912) and Madrid (1913). By comparison, Pelléas was not staged abroad until 1907, when it was given in Brussels, though its international productions in the years 1907–11 were numerous and were spread far and wide, on both sides of the Atlantic – this was a period which set it firmly on the path to worldwide fame .

Of the early stagings of Ariane , by far the most significant, historically speaking, was that given in Vienna at the Volksoper (2 April 1908) where the work’s reception was ennobled not just by the presence and the admiration of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern, but even more by the eloquent and impassioned advocacy of its conductor, Zemlinsky (Beaumont 2000 , 161–2), who conducted it again at the Prague convention of the International Society for Contemporary Music in 1925, in a beautifully crafted and distinctly modern production by the great tenor-turned-director Louis Laber (220–21, 332–5). In Paris, the work continued to be given with success during the inter-war years, and Messiaen’s revelatory experience when he first heard the work at the Opéra in January 1935 – the first time it had been given a Parisian performance away from the Opéra-Comique – was acknowledged in a rapturous letter to Dukas himself, who had been his revered teacher. The impression was so strong that he was moved to write a review which became one of his most elaborated, and most moving, critical essays when it was published in the commemorative issue of La Revue musicale the following year (Messiaen 1935 and 1936 ).

But – at the risk of stating the obvious – Ariane sounds nothing like Pelléas . And it is clear that the hyper-refined style of the latter never was the only possible sound-world for Maeterlinck’s subtle verbal play and inconclusive action. Dukas has a sheer sonorous and orchestral power that Debussy reserves for brief moments (Golaud’s murder of Pelléas at the very end of Act IV, for example); and both his textures and his paragraphing are more conventionally sustained and long-breathed – though his sensitivity to the rise and fall of the dialogue and to the psychological force-field is as acute as Debussy’s, if less neurotically fine-grained and intense. Perhaps most importantly, they share a fundamental approach that is grounded in a prosodical conception of opera, and which, giving primacy to the pacing of the text as much as to that of the action, seeks above all a method of word setting that is true to the accentual and declamatory qualities of the French language, while also maximizing and intensifying whatever incipiently musical value these speech patterns may possess.

If Maeterlinck worked by a kind of controlled ambiguity, writing in a suspended and elusive verbal style that withholds as much as it gives, then much of his expressive ‘message’ consisted not in presence but in absence – what was implied but not stated, and what was called forth through the gaps in the dialogue and the action. He used intentionally simple verbal formulations, making them mysterious by means of frequent ellipses and non sequiturs, and by a refusal to explain potential ambiguities. Moreover the sense of time too was often blurred, both within the overall distribution and sequencing of the action, and in terms of the dramatic setting and its location. These devices were employed because Maeterlinck was primarily interested in evoking deep-seated emotions and psychological states, which he was convinced could not be directly expressed through a traditional, cumulative rhetoric or through the complications of external action, however striking and carefully constructed. This poetic ambiguity found in music an ideal means of ‘prolongation’ (as Debussy called it) of its latent emotional and psychological content. Not only esoteric symbolist ideas about musical essences (reflected, at a distance, in Pater’s famous dictum that all art aspires to the condition of music), but also the more concrete principles of music drama, in which much of the expressive and communicative burden is displaced from the audience’s direct intelligence of the text and its vocal projection on to their imaginative response to the musical continuity, could be fused together to give a new and highly effective vehicle for the realization of Maeterlinck’s aims in the theatre. Indeed it might be argued that his attempt to achieve an atmosphere of openness and ambiguity by purely verbal means actually needed the support of music, as a parallel medium unfettered by the constraints of language, in order to work to best advantage. Music took over where verbal techniques of suggestion left off, and had the incalculable virtue of providing expressive continuity and richness of texture and nuance, where the poet could provide only ellipses and non sequiturs. Music also worked to intensify the unspoken emotions which lay beneath and behind the surface of the text. Thus Debussy’s music in a sense restored to Pelléas a necessary darkness and depth which it otherwise lacked. And yet it is one of the ironies of operatic history that the full scale and significance of this ‘restoration’ did not become fully clear until a later stage of the performance tradition, when the opera had been partly stripped of its envelope of ‘sensitivity’ and was shown with its nerve-endings more fully exposed than before – though without endangering the miraculous beauty of its vocal and orchestral sound-world.

One of the many remarkable things about Pelléas at the craftsmanlike and technical level is how closely, despite the necessary cuts, it engaged with the substance and the letter of the playtext – though Debussy’s skilful changes and reorderings are subtler and more far-reaching in effect than might appear at first sight, especially in the way they serve to manipulate the sense of time and accentuate the idea of circularity and cyclicity, thereby gaining additional space within the action for music to operate as the main expressive and dramatic agent (Grayson 1997 ). Nevertheless, Debussy’s scenario stays relatively close to Maeterlinck’s, and realizes its dramatic potential in a musical style that deepens and enriches the life of the play, transforming it without doing violence to its basic structure . To this extent it stands as a shining example of Literaturoper . Dukas similarly took over the main substance of Ariane from Maeterlinck fully intact, and stayed even closer than Debussy had done to the letter of the text, which he set more or less verbatim. Béla Balázs did no such thing with Duke Bluebeard’s Castle , however. Whereas in Dukas the Bluebeard story is a fully fledged three-act drama of liberation, both spiritual and physical, involving the peasants of the estate and Ariane’s nurse as well as the protagonist herself (Maeterlinck 1901 ; Dukas 1936 ), in Balázs the totality of the action consists in the arrival of Judith with Bluebeard, followed by the opening of the seven doors – an episode which in Dukas is confined to the second half of Act I, and occurs as part of a much larger scenario. Bartók, building on the compactness of Balázs’s initial vision, achieves a spiritual concentration and a sheer psychological force that Dukas, for all the power and sweep of his music, can never quite match.

At a formal and textual level Dukas works within the parameters set by Maeterlinck, breaking through them only by the sheer scale and intensity of his musical thought, by the pacing and the sense of power and depth he brings to the action. The opera is composed, orchestrally and vocally, on a heroic scale, and describes a broad cyclic arc which is musically enacted by the return of the opening orchestral material in the final scene. As in Bartók (surely coincidentally), this material is centred on F sharp, and in both cases the cyclicity represents the female protagonist’s failure to transform the situation in which she has found herself. But here the similarity ends, for the two conclusions are in all other respects very different. In Bluebeard’s Castle , Judith finally joins the three other wives beyond the seventh door, while Bluebeard is left isolated in spiritual and emotional darkness, whereas in Ariane the heroine leaves the stage (in company with her faithful nurse) at the end of the opera, having tried in vain to persuade the other wives to assert their freedom and leave with her. In Ariane the wives sing; in Bluebeard they do not. More surprisingly, perhaps, Dukas’s Bluebeard sings very little. His presence is felt through the general situation and the control he exercises over it; but it is not a physically immediate, vocal and psychological presence, except at two important moments (he intervenes at the opening of the seventh door, and is brought in as a silent captive in the final scene). Nor are these major divergences in scale and scope the only differences between the two scenarios. Whereas in Dukas, following Maeterlinck, the first six doors each reveal a torrent of different jewels (brilliantly depicted with a different timbral and tonal approach in the orchestra), Balázs describes a series of imagined pictures which give Judith – and the audience too – what is in effect a ‘symbolist portrait’ of Bluebeard’s persona, in both its outer and its inner dimensions. His use of the scenic device of the doors acts both as a convenient framework for the action and as a means of access to the synaesthetic and spiritual vision which lies at the heart of his conception, in which the transporting power of music, in carrying us beyond the immediate reality of the scenario into a mythic fantasy-dimension beyond the scenic, is crucial. The opening of the doors is thus part of the psychological grammar of the work, as well as a brilliant piece of stage mechanics, which contrives to give a sense of imaginative breadth and diversity to the action while keeping it compact and outwardly static.

In selecting the episode of the doors as the near-totality of his scenario, Balázs has deliberately jettisoned the greater part of the (external) action laid down for Ariane . He in fact moves so far beyond Maeterlinck, in both a craftsmanlike and a dramaturgical way, that he brings about a fundamental alteration in the inner dynamic of the piece. His text, though obviously built upon the Bluebeard material, can scarcely be called a mere version – as opposed to a complete reworking – of Maeterlinck’s libretto. He was undoubtedly familiar, as Dukas had been, with the original fairytale (Perrault 1697 ), and also used a range of Maeterlinckian motifs and insights. But he builds his own dramatic concept with a staggering sureness of touch that perhaps owes something to other Maeterlinck dramas (Leafstedt 1999 , 37–44), yet impresses above all by its sheer unexampled originality – including not least the brilliant use of the regular folk-ballad metre for the dialogue (which is all cast in eight-syllable lines). It was surely this skilful adaptation of the ‘universal’ character of the symbolist aesthetic to a specifically Hungarian context, as well as the latent Wagnerianism of the underlying dramatic idea (the anguished male protagonist faced with the possibility of redemption by the female), which must have attracted Bartók to this text in the first place. Indeed, it was precisely their shared interest in the marriage of a decisively nationalist-Hungarian stance with an uncompromising international-modernist concern for cultural renewal that joined Bartók to Balázs at this period, and united them both in this project and in The Wooden Prince (Frigyesi 1998 ).

Figure 5.2 Bartók’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle , directed by Herbert Wernicke (Netherlands Opera, 1988). Judith (Katherine Ciesinski) and Bluebeard (Henk Smit). Photo: Jaap Pieper/MAI.

When the text of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle was first published in a Budapest theatre periodical in 1910, it was described as a ‘mystery play’ (Balázs 1910 ). But though there is indeed a (somewhat generalized) Gothic atmosphere in the visual description and presentation of the castle, the sense in which the drama is a ‘mystery’ is not so much medieval as mythic. Far more even than in Maeterlinck and Dukas, it carries a distinctively modern, and potently symbolic, charge. To begin with, the castle itself seems animate. It appears to mourn and suffer, it weeps, sighs, bleeds, and languishes in oppressive darkness. Even as the physical qualities of the setting are conveyed to us in graphic detail through Judith’s discovery and growing awareness of her surroundings, there is a strong sense in which – as hinted at in the spoken Prologue – the entire scenario stands as a grand metaphor for Bluebeard’s psyche, and Judith’s confrontation with it. To this extent the drama as a whole may be read as a journey of two souls towards one another, in the hope of union and liberation, but which ultimately fails when Judith the bringer of light and love fails to overcome the darkness of her husband’s soul. All the detailed physical qualities – evident both in the general aspect of the castle, and in the particular scenes it reveals as the doors are opened one by one – stand in relation to the large-scale opposition of light and dark which governs the symbolism of the entire drama. And it is in Bartók’s tireless efforts to find a compositional equivalent for this process (i.e. of the interaction and contrast between types of light and types of dark, encompassing too the infinitely nuanced range which extends between the two) that the music takes on its profound and haunting dramatic quality. This is a quality not of discursiveness, not of structural functions or thematic working, nor even of musical event and gesture (though there is plenty of the latter in the score), but of what has been memorably called, in connection with Debussy’s Pelléas , ‘tonalities of light and dark’ (Nichols and Langham Smith 1989 , 107ff.).

The communicative power of the Bluebeard story as presented by Balázs and Bartók lies in the tension between the intensely graphic quality of its imagery and the inexpressible ‘beyondness’ of its ideas and content. As with Pelléas , it is surely wrong to see just the immaterial, spiritual message as constituting the essence of the drama. Rather, it is familiar things and everyday perceptions which take on an intensified aura within this ‘visionary’ framework. The combined effect of the stage setting and the suggestive power of music transforms the imagined scenes ‘revealed’ by the opening of the doors into true visions. There is a process of stylization and defamiliarization, but its purpose is to achieve not so much strangeness per se as an intensification of ‘the real’. In symbolist art, the physical characteristics of what is represented are often more graphic for the spectator than in realist art – because they are treated selectively and in greater isolation than they would be within a fuller, and inevitably more cluttered, realist context. There is an intensity of focus on the important images that creates a sense of heightened perception and psychological response, without obliterating the manifest external qualities that have triggered them. The possibility of achieving such effects is one of the great strengths of the theatre as a medium, and its potential is realized through the expressive tension between the theatrical framework and the musical-verbal language which is deployed within it. This, too, is a phenomenon which unites the realm of stagecraft, in its physical and visual aspect, with that of music and the evocative power of the word.

And so the ‘mystery’ into which Judith is initiated is not an evasive Gothic dream, but the unseen realities of her husband’s soul. The drama is a journey of discovery, and of realization – a realization, in the end, of the depths of Bluebeard’s despair and inner darkness. It is a journey which, through the agency of Bartók’s music and the singing presences we see and hear on stage (or, indeed, inside our own minds), we too are enabled to make, vicariously and sympathically. There is an overall movement from initial darkness (their arrival in the great hall, followed by the torture chamber and armoury: Doors 1–2), through the visions of beauty and radiance (treasury, garden, kingdom: Doors 3–5), back to an even more sinister darkness, enlivened only by a baleful glimmer (the lake of tears: Door 6). This is then followed by the bittersweet spectacle of the three bejewelled wives (Door 7), in which there is a truly heartrending mixture of the light and the dark: a return to the initial Stygian gloom, but coloured by onstage light from various sources, including a narrow beam of moonlight and the brightness of the women’s apparel.

The opera as a whole thus describes the opening and closing off of hope: darkness (initially centred on F sharp), followed by an influx of light through the three central doors (including the glory of Bluebeard’s kingdom, centred on C), which is then closed off more fully and more poignantly than before. This dramatic outline reinforces the sense of ultimate despair and gives us the full measure of Bluebeard’s tragedy when he sings, at the very end: ‘And now, forever, all shall be night . . . night . . . night . . .’ (éjjel . . . éjjel . . . éjjel . . .). Musically, this final closing of the door of hope is expressed through the return of the pentatonically organized music, again centred on F sharp, from the beginning of the opera, but now cast in a more dissonant and anguished form. Significantly, it took Bartók a long while to arrive at this conclusion in its final shape. He first wrote a simpler, more translucent ending (1911), seemingly modelled on the closing section of Pelléas , before deciding to make the final stages blacker and more painful. In 1911–12 Bluebeard’s final line (quoted above) was added, other dialogue deleted, and various musical alterations made. Then in 1917–18 the music was worked over once more (in preparation for the belated premiere on 24 May 1918), and its sound-world made more dissonant, reflecting general changes in Bartók’s compositional language in the intervening years, but also his by now darker conception of the ending of the drama (Leafstedt 1999 , 142–4 and 153–8).

Sound-worlds: musical dramaturgy and the poetics of opera

In working towards a distinctively symbolist version of musical drama, the question of the action and subject matter was, as we have already begun to see, only half the problem. The ability to reinvent the operatic scenario, and to envisage what kinds of expressive and psychological effects might be drawn from it, depended on a composer also being able to find an appropriate musical idiom within which to work. Expressive force of style was needed to sustain the dramatic vision convincingly; and only when music was fully integrated as the main vehicle of the action would the aspiration towards a form of total expression be fulfilled. As both Debussy and Dukas had done, Bartók took a deeply empirical approach to his compositional task and worked on his opera intermittently over several years, constantly refining various aspects of its style and sound-world, as close study of the surviving sources reveals (Kroó 1981 and 1993 ; Leafstedt 1999 , 125–58). Like Debussy, he paid particular attention to the refinement of details in the rhythmic delineation and declamatory profile of the vocal parts – a procedure which is of special interest in regard to the broader aesthetic concerns of the symbolist operatic project. Similarly to Debussy and Dukas, he envisaged a fundamentally syllabic declamation, grounded in the speech patterns of the language (Hungarian in his case, French in theirs), and seeking to give an audibly ‘national’ character to the vocal lines .

This approach to word setting was characteristically radical, but not by any means unique. Composers as diverse as

Strauss and

Puccini had been moving towards the use of a freer, more flexible kind of vocal line, at least in certain areas of their operas – a vocal line built up from small rhythmic and melodic shapes which corresponded in some degree to the accentual patterns of the words, rather than arbitrarily seeking to fit the text beneath broader, independently conceived melodic spans. And a radical individualist such as

Janá ek, in moving through the various phases of revision of

Jen

ek, in moving through the various phases of revision of

Jen fa

(1903–4, 1906, 1907–8) and on towards the composition of his later operas, came more and more to see in ‘speech melodies’ (náp

fa

(1903–4, 1906, 1907–8) and on towards the composition of his later operas, came more and more to see in ‘speech melodies’ (náp vky

) the main source of his melodic ideas within the vocal line. As in the case of Debussy and Bartók, it would be wrong to see in these melodic shapes a direct transcription of linguistic accentuation in any very literal sense. As with other aspects of opera, there is a strong element of stylization and ‘idiomatic translation’ involved, and the resultant melodic style in the end stands or falls by its own merits. The idea of faithful accentuation ultimately remains an aspiration rather than an objective technique, its goal being obviously as much rhetorical as strictly phonetic. Many operas written with the sounds and articulation of the spoken language uppermost in the composer’s mind still survive linguistic translation triumphantly (

Jen

vky

) the main source of his melodic ideas within the vocal line. As in the case of Debussy and Bartók, it would be wrong to see in these melodic shapes a direct transcription of linguistic accentuation in any very literal sense. As with other aspects of opera, there is a strong element of stylization and ‘idiomatic translation’ involved, and the resultant melodic style in the end stands or falls by its own merits. The idea of faithful accentuation ultimately remains an aspiration rather than an objective technique, its goal being obviously as much rhetorical as strictly phonetic. Many operas written with the sounds and articulation of the spoken language uppermost in the composer’s mind still survive linguistic translation triumphantly (

Jen fa

initially made its way on the international stage in German, with great success, beginning with the important productions given at

Vienna and

Cologne in 1918 and

Berlin and

New York in 1924), even if few would deny that the original language, when well declaimed, brings with it a dimension of colour and expressive idiom that is ultimately irreplaceable.

fa

initially made its way on the international stage in German, with great success, beginning with the important productions given at

Vienna and

Cologne in 1918 and

Berlin and

New York in 1924), even if few would deny that the original language, when well declaimed, brings with it a dimension of colour and expressive idiom that is ultimately irreplaceable.

Nevertheless, for all these common developments across Europe, a passionate concern with prosody was one of the major compositional preoccupations to which the symbolist aesthetic gave rise. For Debussy, it was not just a question of the génie de la langue (a feeling for the distinctive qualities of French declamation which was one of the things he most admired, for example, in Rameau), but also one of psychology and dramaturgy in a broader sense. In the first place, following Maeterlinck, he was aiming at a clear evocation of humanity and human emotion, in as simple and direct a form as possible, despite the apparent stylization and ambiguity of the dialogue forms in the playtext/libretto. And this need for clear declamation was combined – at least in his own mind – with what he saw as the distilled, limpid quality of expression, full of nuance but never obscure, at which he was aiming:

It is important to insist on the simplicity [to be found] in Pelléas : I spent twelve [recte ten] years striving to remove from it everything superfluous that had somehow slipped in unawares – but I never set out to revolutionize anything at all. . . . I merely tried to show how people who were singing [in a drama] could at the same time remain human and natural, without needing to become like madmen or ciphers.

(Debussy, in Lesure 1993 , 247)

His technique of word setting – one that, as studies of the sketches and drafts have shown, was a constant, almost obsessive preoccupation during the long years of writing the opera – seems to have grown more decisive and more refined as he went along. Such flexible declamation, in which the kind and degree of emotion a character might be feeling at any given moment could in theory be mirrored in the vocal line, and in the way this line was amplified and intensified by the orchestra, was closely related to Debussy’s general views on dramatic expression, which embraced not just prosody but also the broader musical life of the piece as a representation of the inner life of the characters:

It is quite wrong to think that a fixed melodic line (une ligne mélodique arrêtée ) can be made to contain all the infinite nuances through which a character passes [during the course of a drama]: that’s not just an error of taste but a fundamental error (une faute de “quantité” ). So that, if there’s little or no trace of . . . a symphonic thread in Pelléas , this is in reaction to the nefarious neo-Wagnerian aesthetic which claims to be able to render, simultaneously, the emotion expressed by a character and the inner reflections which cause him [or her] to act as they do. In my opinion these are two contradictory operations, from an operatic point of view, which in combination can only serve to weaken or undermine one another. It’s surely far better that music should attempt by simple means – a chord? a curve? – to represent the [various] ambient and psychological states as they follow one another (les états d’ambiance ou d’âme successifs ), without forcing them to awkwardly follow the pattern of a preordained symphonic development, which is always arbitrary . . .

(246)

Here we see that, however separate the spheres of declamation and of the orchestral continuity might appear to be at a technical level, in Debussy’s thinking they are very much two aspects of a greater whole. And it is this extreme degree of linkage between the various musical and scenic elements – or dimensions – of the score that characterizes the approach of all three composers. Yet again, this preoccupation stems ultimately from Wagner. But the symbolist ethos is perhaps even more radically synaesthetic, at least in aspiration – and so the way the orchestra was made to relate to what was happening in the vocal line at any given moment was crucial for each of them in different ways. Bartók’s extensive revisions to the details of the declamation in Bluebeard show this preoccupation just as clearly as do Debussy’s. And despite the greater breadth and solidity of the orchestral writing in Ariane by comparison with Pelléas , a stylistic feature which Dukas counterbalanced by consciously making space for the voice where necessary, he too was fundamentally concerned with speech values, drawing in part no doubt on the example set by Debussy . Writing in 1927 to Guy-Ropartz about a forthcoming concert performance of Ariane , Dukas emphasized the fully integrated relationship of the musical fabric as a whole to the rhythms and pacing of the vocal declamation, advising him that

as a general rule, [you should] beat time [conduire = ‘set a tempo’] at the speed of spoken theatrical diction. This is essential for the first chorus as it is [also] for the soli . As soon as the voices enter the tempo must be based on the rate of delivery of stage declamation. And your four main beats should give, with the appropriate subdivisions, a resolute allegro .

(Dukas, in Favre 1971 , 160)

All these observations serve to emphasize the centrality of the voice – a centrality which brings with it the corollary of an orchestral continuity that is able to endow the words with a rich unspoken hinterland of complex, nuanced emotion, without ever threatening to overwhelm or undermine them .

Schoenberg, too, saw the importance of giving primacy to the voice, both for expressive reasons (the voice is the primary vehicle of human emotion in life, and a fortiori in opera), and also for clarity’s sake (only with a fully resolved and articulate vocal part can the human situation be made intelligible). But typically for Schoenberg, he complicates this essentially simple observation, twisting it so as to give it a more theoretical slant. He asserts that, in consequence of this primacy of the voice, all the compositional material should in some way be encapsulated or ‘embraced within’ the vocal line (Schoenberg 1975 , 106): the singing and declaiming voice is audibly to the fore, while the psychological background, with all its emotional ambience and implied undercurrents, is provided by the orchestral amplification of this ‘basic line’. Like Debussy, though in far less polemical and censorious terms, Schoenberg claimed that Wagner, despite acting with excellent dramatic ideas and intentions, had nevertheless overloaded and at times over-structured his orchestral textures, with the result that the freedom of both the vocal line and the dramatic movement was compromised (105–6). Yet if he doubted the dramatic appropriateness of such an overly symphonic approach to thematic working and paragraphing within the orchestra, Schoenberg never doubted the viability of the general Wagnerian vision. It needed to be taken further, transcended even, but was groundbreaking in many of the right ways. He saw that Wagner had taken a bold and necessary path in seeking to reformulate the whole relationship between the sustained impact and mobility of the dramatic message and the continuous musical unfolding towards which he had been working for most of his career. Perhaps the crucial discovery he had made, along the way, was how to shape the orchestral continuity so as to render every change and every turn in the dramatic situation immediately clear to the audience. In through-composed opera the composer needed to be able to signpost the drama as far as possible at every level – scenic, atmospheric, psychological – with a real sureness of touch.

This sense of continuity, of the continuous unfolding of the orchestral materials, enabled a rapidity and a responsiveness to nuance in the psychological texture of the piece which stands at the heart of both the symbolist and the expressionist vision. This went hand in hand with the new general relationship of music to theatre, alluded to by Schoenberg, and also with the new approaches to prosody and vocal writing, and to the way orchestral textures were constructed, which we have already observed. For a strong tendency to downplay the sheer audibility and strong profiling of motives (as Wagner had understood them) is a key technical aspect of this approach to the handling of the orchestra in both Pelléas and Erwartung . If the sheer fluid beauty of Debussy’s sense of form ultimately works against the creation of solid musical architecture, it nevertheless enables precisely this kind of subtle psychological play within the fabric of the drama. The technical means which make this possible consist in finding motivic shapes that can merge and combine with unselfconscious ease, by virtue of their shared intervallic elements:

In Pelléas every motif shares the same intervals with every other: they can be fragmented into accompaniment or ostinato; every ostinato or accompaniment [figure] can emerge as a motif; and the harmony everywhere consists of these same intervals superimposed into chords . . . The large-scale corollary of this is that there is no ‘architecture’ in Pelléas . . . [whose] very special felicity . . . [consists in] the way in which the turn of the speech, a passing reference, an underlying feeling or mood, immediately impresses itself upon the local expression. The music in Pelléas actually reacts to the words rather than, in Wagner, being the expression and embodiment of them .

(Holloway 1979 , 137)

If both Debussy’s and Schoenberg’s motivic technique and approach were ultimately derived from the Wagnerian model, they sought a version of it that was internalized and distilled into something less self-dramatizing and less strongly projected, and was subsumed within an overall texture whose primary purpose was psychological reaction and evocation .

Symbolism and expressionism

From its emergence in the 1890s symbolism rapidly grew into a European phenomenon, becoming rooted and acclimatized in Scandinavia, Russia, Germany and elsewhere in central Europe, including Hungary, as well as in its homeland in France and Belgium (Balakian 1982 ). There were productive ties to Germany in particular, not least because strong and influential artistic personalities came under the spell of symbolist ideas, both through their own visits to Paris and through the diffusion of Maeterlinckian and Mallarméan texts in printed form. The poet Stefan George, for example, was in Paris during 1889 and for a brief period had attended Mallarmé’s Tuesday evening literary and intellectual gatherings (where Debussy was also a valued if somewhat sporadic guest). And in later years, after going back to Germany, he became a reference point for intellectual and artistic circles with symbolist leanings and aspirations, in Munich and elsewhere. Kandinsky also went for a time to Paris (1906–7) and, on his return to Germany, became closely involved with the Munich Artists’ Theatre (Münchener Künstlertheater), a group with strong symbolist interests in the realm of dramatic spectacle and stage design (Weiss 1977 and 1979 ).

George was, of all contemporary writers, the preferred poet of the Schoenberg circle during the pre-First World War period; and the exchange of ideas between Schoenberg and Kandinsky was in many ways decisive for them both during the crucial years 1911–14. Moreover, the rapidity of their artistic sympathy when they first became acquainted in January 1911 can be accounted for by the fact that during the immediately preceding years – the years of Erwartung and free atonality, of the Harmonielehre and Kandinsky’s epoch-making text Concerning the Spiritual in Art , which explicitly mentions Wagner, Maeterlinck and Debussy (Kandinsky 1965 ) – they had been working towards similar aesthetic goals in parallel, but independent ways. Moreover, they both held strong views on the aims and nature of dramatic representation which chimed in with the broadly anti-realist stance then current among the avant-garde in Austria and Germany:

Kandinsky abstracts all unessential transitory characteristics in order to throw into relief the intrinsic, unchangeable shape of things, . . . [whereas] Schoenberg . . . is closer to Maeterlinck’s de-individualized characters who represent something beyond themselves . . . They shared the Expressionists’ disgust with the theater of edification, with the socially critical plays of Naturalism, and their mistrust of the word [and verbal communication] in the established sense . . . They also shared a . . . belief in . . . showing the essence of things, only revealed to the artist in visionary ecstasy, to other human beings as primordial truth . . . Like most of the Expressionst dramatists, [they] also wanted . . . to reveal transcendental forces and relationships, . . . which no longer fit into a pattern of causality; thus the stage is no longer a mirror of the realistic world, but one of ‘true being’, beyond the seeming world of material things .

(Hahl-Koch 1984 , 163–4)

No doubt this list of aspirations goes well beyond that of the symbolists, certainly in tone and emphasis if not in ideas per se . Any French thinker would probably have fought shy of the notion of visionary ecstasy or of primordial truth, let alone that of ‘true being’, and would have been content with a more circumspect, less prophetic, and perhaps more ironic approach to such serious topics. And although the symbolist approach certainly aimed to evoke interior realities and states of the soul, it is difficult to imagine Debussy having much liking for the fervour of the German expressionists’ overtly spiritualist and philosophical rhetoric, which he would surely have seen as needlessly grandiloquent and in poor taste. Such points of contact and connection as there are do not in themselves, even taken together, constitute a consciously linked aesthetic or artistic programme. But they do help to bridge the cultural gap, at the level of underlying and formative ideas, between the world of symbolism and that of expressionism. Symbolist poetics had emerged partly out of the intensive French response to Wagner in the 1880s and 1890s. And it was the broader insights and aesthetic goals of symbolism that in turn now re-entered the vast sea of late-romantic culture in Germany, and especially the post-Wagnerian world of musical drama, as an invigorating current that helped to bring about the cultural and artistic transformation without which Wagner’s legacy could scarcely have been turned into a viable expressive vehicle for drama in the changed circumstances of modern times.

These observations help to sketch in a context which lends support to the notion that Erwartung is at root a symbolist opera – one that is conceived with a German psychological slant, and felt with an expressionistic intensity and edge, as well as being expressed in Schoenberg’s free-atonal style without reference to French stylistic models, but which still shares important underlying principles with the Maeterlinckian vision and its derivatives. In this sense, there is a strong kinship of aims and ideas between symbolism and expressionism, even if they express themselves very differently, and even if their cultural paths diverge more or less from the very beginning. The interpenetration of inner and outer worlds is similar, as is the expressive priority given to what might be called the ‘psychic dimension’ of the action. Certainly, whatever in Maeterlinck’s aesthetic is couched in the language of ambiguity and evasion takes on a much sharper psychological edge in Schoenberg. Yet the Pappenheim libretto for Erwartung uses the imagery of nature with the same kind of selective intensity as Maeterlinck does – and the nocturnal phenomena of light (moon, shadows, appearances) and movement (breeze, branches, sounds) are lavishly provided within the text for Schoenberg to work his orchestral magic on. And so, with the combined suggestive force of voice and orchestra, they are simultaneously both a symbolic projection of the Woman’s fears and anxieties, and a representation of the external perceptions that have triggered them.

The flexibility and multivalency of the orchestral continuity was another point they had in common. The orchestra may articulate physical movement, effects of atmosphere (the wind, the light, the play of natural forms), and other perceptual or ambient qualities. But above all it effortlessly bridges the gap between the fragile exterior world of human perception and the psychic world within. In their approach to instrumentation, they shared an approach which favoured the avoidance of mixed colours, or at least sought unprecedented orchestral combinations which allowed primary instrumental colours to speak both pure, as clear individual ‘voices’ within a freely polyphonic texture, and as combined in new, often radically unconventional ways. Each of them had an ear for such sonorities, both in themselves, as effects of timbre and colour in their own right, and as expressive metonymies for states of mind or being. As Webern observed of Erwartung as early as 1912 (and here we may briefly note in passing just how well he and Berg obviously knew this score from its inception, despite its belated premiere at Prague, under Zemlinsky, on 6 June 1924):

The score of this monodrama is an unprecedented event. All traditional formal principles have been severed; there is always something new, presented with the most rapidly shifting expression.

This is also true of the orchestration: a continuous succession of sounds never heard before. There is no measure in the score that doesn’t demonstrate a completely new sound pattern. The treatment of the instruments is entirely soloistic . . . [Of the chordal voicing:] Each color derives from an entirely different timbral family. There is absolutely no blended sound [Mischklang ] here; each color resounds soloistically, unbroken . . .

. . . Thus this music flows by, tightly bound forms along with disintegrating ones, breaking up recitative forms, giving expression to the most hidden and faintest stirrings of emotion.

(Webern 1912 , 227–30)

Such obsessive concern with timbre and texture, at both the general and the more detailed, fine-grained level, illustrates very well the increasingly important role played by sheer sonority in modern opera, not just as an effect of colouristic originality, but as a means to creating a truly distinctive sound-world for the chosen subject matter. As generic traditions of opera began to lose their hold as a vehicle for new work within an increasingly fixed, historicized repertory, so the importance of the individual project, and the ad hoc working out of all the dramatic, musical and scenic parameters in relation to the character of the subject, increased. This again was grounded ultimately in the Gesamtkunstwerk idea, but went far beyond Wagner in a way he could scarcely have envisaged it being applied. This too is a sphere of operatic development, whether viewed in a broadly cultural or in a more closely technical sense, that confirms the underground affinities between the symbolist and expressionist approaches, quite apart from the question of possible historical continuities and moments of demonstrable influence.

One final aspect of the handling of orchestral texture which links Schoenberg to symbolist practice is its aspiration towards an aesthetic of sustained eloquence, transforming the moment-to-moment unfolding of the psychological action into free musical form. In a 1912 diary entry Schoenberg considered the – fundamentally paradoxical – linkage of the concept of the obbligato line with the non-repeating spontaneity of recitative, and brought this combined idea into relation with the idea of unendliche Melodie . This strongly suggests that, like Debussy, he was attempting to break down the powerful musical constructs of the Wagnerian imagination and distil away what he felt to be its excessive orchestral substance, in order to arrive at an expressive essence of it couched in a quite different musical and textural style. In this, the brilliantly anti-constructive phase of Schoenbergian atonality, which was reacting with every fibre of its being against the equally brilliant constructedness of Wagner, we are confronted by the paradox that Erwartung , with its aesthetic of non-repetition, free unfolding, athematic variation, pervasive asymmetry and radical atonality, was none the less, despite these divergences, a profoundly Wagnerian work at a strongly sublimated remote or background level (Dahlhaus 1987 , 145).

The quality of ‘endlessness’ in unendliche Melodie was in this sense a dramatic and epistemological ideal, rather than anything more literalistic having to do with the melodic character of themes and textural combinations of such themes. It is thus at root a psychological and rhetorical quality more than it is a stylistic one in the narrower, technical sense. If, according to Wagner, ‘a musical structure is “melodic” to the extent that it is eloquent’ (146), then asymmetrical, athematic, non-repeating ‘free flow’ or ‘perpetual variation’ in the orchestra not only is no bar to lucid expression, but may, in extreme human states, be the only true and adequate expressive means. It is by this measure that Erwartung is ‘case study and construction in one, [in which] the seismographic registration of traumatic shock becomes, at the same time, the structural law of the music’ (146 and 149, citing Theodor W. Adorno). This aesthetic of direct ‘idiomatic translation’ from the psychological and the atmospheric to the musical is the point of contact at which the symbolist and expressionist operatic worlds touch .

The literary and aesthetic as well as the more centrally dramatic concerns of symbolism may thus be seen to have influenced the expressionist approach to opera at a deeply implicit, formative level. But there are other connections, too, of a more immediate and concrete kind. We have already observed how Berg , in the company of Schoenberg and Webern, attended the Viennese production of Ariane conducted by Zemlinsky in 1908. And although, over the longer term, the operatic models of both Dukas and Debussy were equally important to him – surely more as an approach and an aspiration, than at a stylistic or constructional level – Berg was obviously immediately enthralled by Ariane . During the summer of 1909, in the year following the performances at the Volksoper, he even suggested to his future wife Helene that he might play through Ariane to her at the piano, in company with such other luminary scores as Parsifal and Elektra (Grun 1971 , 89). And he later admitted to Ernest Ansermet that the example of Pelléas had inspired him to use orchestral interludes as an integral part of the drama in Wozzeck , and that the way Debussy had invested each scene of his opera with a distinctive, localized expressive character had given him the idea of using a varied sequence of abstract instrumental forms as an underlying constructive and dramaturgical device (Carner 1983 , 178).

Here, then, is a thought-provoking link between the symbolist works and Berg’s operatic practice: a way of writing in a continuously unfolding and sustained manner, yet with maximum differentiation from scene to scene, so that the phases of the drama may be clearly and audibly characterized. Such considerations are less of a problem in Erwartung , where the piece as a whole is short and condensed, and the totality of the action is constituted by the expansion of a brief moment of highest psychic intensity and complexity (‘In Erwartung the aim is to represent in slow motion everything that occurs during a single second of maximum spiritual excitement, stretching it out to half an hour’; Schoenberg 1975 , 105). But if a composer wished to adopt the idea of the orchestral continuity as the foundation of a drama with a cast of characters and a sequential action, and in doing so give voice not only to the psychological ‘atmosphere’ in which they are all enveloped, but also, just as importantly, to an articulate series of situations, then some effective means of contrast and internal sectionalization was essential. And it was equally essential to achieve this sense of ongoing contrast without recourse to over-specific motivic design, or to an overtly discursive or developmental orchestral approach. Berg himself did of course use a closely woven inner tissue of thematic ideas; but, as with his underlying constructive forms, this dimension of his scores is in fact handled very fluidly, and is to a considerable extent subsumed within the expressive ‘scenic and psychological flow’ of the music as a whole. Here, too, there is an implied affinity with the ‘tonalities of light and dark’ theory – the composer’s interpretative grasp of the expressive ambience of every situation (potentially of every moment), with all its simultaneous physical and psychic impulses, would govern the course of his musical invention and formal sense, as he sought to invest each scene with its appropriate sonic character .

Legacy: later perspectives

My argument has been that symbolist opera in the strict sense was a relatively contained, short-lived phenomenon, just as Maeterlinck’s period of intense theatrical activity in the 1890s had been short-lived, but that it had long-range consequences which went well beyond the confines of its own historical moment. Both these cultural manifestations of symbolist ideas – the theatrical and the operatic – were powerful and ultimately long-lasting, not merely in what they aspired to but in what they actually managed to achieve in so short a space of time. If symbolism’s aims and ideals were in part absorbed into the expressionist project, then it is chiefly in this guise that they lived on. It was the range of sound-worlds conjured up by (largely Austro-German) expressionism which were to be one of the decisive aural influences on the modernist avant-garde, in both its free-atonal and its serial manifestation; so that the renewed pursuit of hyperexpressive opera in the 1960s and 1970s, in taking its cue from Wozzeck and Erwartung , and increasingly from Berg’s Lulu as well, was invisibly connected to earlier symbolist ideas by this means. And the idea of an expressive ‘scenic and psychological flow’ as the raison d’être of the orchestral continuity, liberated from the symphonic paragraphing and dense leitmotivic networks of Wagner, was exemplified and further developed primarily through the ongoing reception of Berg and Schoenberg. So that, even if acoustically and stylistically there is no audible link between, say, Debussy’s 1904 incidental music commissioned for André Antoine’s production of Le Roi Lear (though the composer admittedly never showed any sign of wanting to treat the subject operatically) and Aribert Reimann’s shatteringly powerful Lear (1978), the latter could scarcely have come to be as it was without the mediating histories of symbolist and expressionist opera which had first internalized and tamed the Wagnerian legacy, before transforming it and extending it in new directions, in a cumulative process which inevitably lost all contact with its own origins.

If the Wagnerian vision remained a strong one, still fascinating and capable of further evolution, the methods and the aesthetic as well as the stories and scenarios had had to change, and indeed go on changing. Wagner’s heroic championing of an extended operatic language (of tonality, of the contrapuntal combination of themes, of the stretching of the principle of theatrical gesture and the expressive moment to encompass a musical process of vast symphonic breadth) was positioned at a historical crux, and had to be diverted – by the sheer force of a strong, though not necessarily revolutionary, musical personality – into something else. This is surely the sense in which Debussy referred to Wagner as a sunset rather than a dawn, and sought a way of internalizing and sublimating what he continued to love and admire, while simultaneously feeling the necessity of denial and confrontation, and finally of transcendence (Holloway 1979 ; Abbate 1981 ).

It was not until the greater diffusion of the

Berg operas in the theatre after World War Two, as well as the rejuvenation of

Pelléas

and its recasting in the role of a ‘universal’ rather than a more narrowly focused ‘national’ opera (as gradually happened also with

Janá ek), that these dramaturgical questions could be more fully and more deeply explored, both in terms of stage production and at the critical and psychological level. To consider briefly a contrasting example will serve to broaden and also reflect back on the scope of this latter stage of the argument, in both a historical and an aesthetic perspective. For one can hear the apparently direct – yet from the vantage point of the later twentieth century ‘retrospective’ and post hoc

– influence of Wagner on the centrally modernist, and still broadly expressionist, idiom of a work such as Harrison

Birtwistle’s Gawain

(1991, revised 1994). This three-act opera on the grand scale, having taken its mythic subject matter and atmosphere from Arthurian legend as a dramatic starting point, triumphantly dares to bring back an audibly Wagnerian dimension of sound and gesture and graft it on to an idiom that, like

Reimann’s, has come straight out of something much more recent, and without obvious surface connections either to Wagner or to symbolism.

ek), that these dramaturgical questions could be more fully and more deeply explored, both in terms of stage production and at the critical and psychological level. To consider briefly a contrasting example will serve to broaden and also reflect back on the scope of this latter stage of the argument, in both a historical and an aesthetic perspective. For one can hear the apparently direct – yet from the vantage point of the later twentieth century ‘retrospective’ and post hoc

– influence of Wagner on the centrally modernist, and still broadly expressionist, idiom of a work such as Harrison

Birtwistle’s Gawain

(1991, revised 1994). This three-act opera on the grand scale, having taken its mythic subject matter and atmosphere from Arthurian legend as a dramatic starting point, triumphantly dares to bring back an audibly Wagnerian dimension of sound and gesture and graft it on to an idiom that, like

Reimann’s, has come straight out of something much more recent, and without obvious surface connections either to Wagner or to symbolism.

Both Reimann and Birtwistle stand, independently of one other and of late twentieth-century operatic culture in general, as heroic reaffirmations of a large-scale approach to opera which seeks to harness all the power and reach of mythic narrative and bring it together with a musical idiom that allows no compromises or half-measures. The resulting works, when experienced as live theatre, both lay claim to something almost cosmic, as well as numinous and potentially tragic – though the magical quest-element of Gawain diverts this tragic potential into an atmosphere of gritty heroic determination in the protagonist’s struggle for self-realization in the face of far greater forces than just his series of one-to-one encounters along the way. Lear responds to the enormity of the Shakespearean subject and its dramatic themes with music of an extremity which is commensurate with the terrible human conflicts and realizations which stand at the heart of the story. Yet the very massiveness and at times violence of its sound-world take us beyond the individual human plight, however heartrending, and into something bigger – a larger dimension which lies beyond the scenic and beyond the physical tout court , beyond even the pathos of shared human emotion. We are moved into a ritualized tragic world against which the protagonist and the audience are both powerless. And this miraculous (if supremely painful and despairing) shift is fundamentally brought about by Reimann’s deployment of his vast orchestra, or rather, by the orchestra in its relation to the voices and to the physical presences on stage. As in Gawain , the orchestral conception is central. It is the force-field generated by the tension between the immensely varied vocal writing and the – at times massively subdivided, often clustered – instrumental textures which surround the voices, that gives the work its unique visceral impact in the theatre .

Certain dramaturgical features ultimately traceable back to symbolist practice are still profoundly there in Reimann: the lack of regularly paragraphed musical forms and thematic profiles; the adoption of a musical continuity which renders the moment-to-moment flux of the dramatic situation while at the same time saturating it with an often almost unbearably intense level of expressivity that at times approaches the cataclysmic; the exploitation of physical extremes of sound (an extension of the principle of ‘tonalities of light and dark’ used in Pelléas or Ariane or Bluebeard ) to give a powerful sense of dramatic differentiation and contrast without becoming symphonic or discursive; the use of the orchestra not just to give dramatic ambience to the scenes and to support the voices, but to propel and animate the forces of nature which approximate, in this epic tragedy, to those of destiny; and the pervasive use of free vocal writing, ranging outwards from middle-range syllabic declamation to more sustained if still angular lyric lines, explosive vocal gestures, hysterical coloratura and tense parlando. Reimann had clearly taken these stylistic procedures from sources many times removed from Debussy or Bartók, though strong traces of Erwartung and more importantly of Berg (both Wozzeck and Lulu ) can be heard in this as in many other neo- expressionist operas of the 1960s and 1970s – most strikingly of all, perhaps, in Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten of 1965. But the immense distance travelled since the pre-1914 world serves to emphasize once again what the real necessity had been of remaking the Wagnerian legacy at an absolutely fundamental level, yet without suppressing its most vital and powerful expressive impulses .

Debussy himself saw very clearly that it is, finally, its capacity for profound psychological and situational expression within the context of a sensitively drawn human drama which gives any opera its lasting power and relevance, and that refinements of style and atmosphere or new features of construction and invention are finally subordinate to the projection of this human content. As if in premonition of what would happen during later years, he had insisted already in 1902 that

the drama of Pelléas , . . . despite its dreamlike atmosphere, [in fact] contains far more of humanity than do the so-called ‘documents of real life’ (les soi-disant «documents sur la vie» ) . . . There is in it a language of evocation, the sensibility [and emotion] of which [I judged] suitable to be prolonged in music and in the ‘orchestral décor’ . . . I do not claim to have discovered everything in Pelléas . But I have tried to forge a path which others will be able to follow, extending and enriching it with personal discoveries which perhaps will be able to deliver dramatic music from the heavy constraints which have burdened it for so long.

(Debussy , in Lesure 1987 , 63–4)

Along with the many explicit references to his struggle to absorb and transform Wagner, this comes as close as any of his observations to identifying the essential, yet also the most difficult and elusive of tasks facing any operatic composer working in the twentieth century – that of finding an approach to musical form, in the realm both of vocal writing and of the orchestral continuity, that is aesthetically persuasive and consistent, yet at the same time fully transparent to the human values and the moment-to-moment life of the unfolding drama which it embodies .