“REBECCA”: A CINDERELLA-LIKE STORY ■ “I’VE NEVER RECEIVED AN OSCAR” ■ “FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT” ■ GARY COOPER’S MISTAKE ■ IN HOLLAND, WINDMILLS AND RAIN ■ THE BLOOD-STAINED TULIP ■ WHAT’S A MacGUFFIN? ■ FLASHBACK TO “THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS” ■ “MR. AND MRS. SMITH” ■ “ALL ACTORS ARE CATTLE” ■ “SUSPICION” ■ THE LUMINOUS GLASS OF MILK

FRANÇOIS TRUFFAUT. I take it, Mr. Hitchcock, that you came to Hollywood expecting to do a film on the Titanic, but instead you made Rebecca. How did that happen?

ALFRED HITCHCOCK. David O. Selznick informed me that he’d changed his mind and had acquired the rights to Rebecca. So I said, “All right, let’s switch!”

F.T. I thought you might have had something to do with that switch. Weren’t you already interested in filming Rebecca before coming here?

A.H. Yes and no. I had an opportunity to buy the rights while I was shooting The Lady Vanishes, but the price was too high.

F.T. The name of Joan Harrison appears on the credits of Rebecca and on several of your British movies. Did she actually work on the screenplay or was that simply a way of representing you on the credits?

A.H. At one time Joan was a secretary, and as such she would take notes while I worked on a script, with Charles Bennett, for instance. Gradually she learned, became more articulate, and she became a writer.

F.T. Are you satisfied with Rebecca?

A.H. Well, it’s not a Hitchcock picture; it’s a novelette, really. The story is old-fashioned; there was a whole school of feminine literature at the period, and though I’m not against it, the fact is that the story is lacking in humor.

F.T. Maybe so, but it does have the merit of simplicity. Joan Fontaine, Laurence Olivier, and Judith Anderson were an interesting trio: A young and shy lady’s companion miraculously marries the handsome master of Manderley, whose first wife, Rebecca, has died in mysterious circumstances. When they get to the grandiose family mansion, the young bride feels inadequate to her new situation. Increasing her lack of self-confidence is the sinister, domineering housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, whose obsessive devotion to Rebecca is manifested in active hostility to her new mistress. Then a new investigation into Rebecca’s death brings out some unpleasant facts that cause Mrs. Danvers to set fire to the house and commit suicide. With the destruction of Manderley and the death of her tormentor, the heroine’s sufferings come to an end.

Anyway, this was your first American project and I imagine you must have felt a little intimidated at the idea of undertaking it.

A.H. Well, not exactly, because in fact it’s a completely British picture: the story, the actors, and the director were all English. I’ve sometimes wondered what that picture would have been like had it been made in England with the same cast. I’m not sure I would have handled it the same way. The American influence on it is obvious. First, because of Selznick, and then because the screenplay was written by the playwright Robert Sherwood, who gave it a broader viewpoint than it would have had if made in Britain.

F.T. It’s a very romantic theme.

A.H. Yes, it’s romantic. Of course, there’s a terrible flaw in the story, which our friends, the plausibles, never picked up. On the night when the boat with Rebecca’s body in it is found, a rather unlikely coincidence is revealed: on the very evening she is supposed to have drowned, another woman’s body is picked up two miles down the beach. And this enables the hero to identify that second body as his wife’s. Why wasn’t there an inquest at the time the unknown woman’s body was discovered?

F.T. Yes, that is a coincidence, but the whole story is so completely dominated by the psychological elements that no one pays any attention to the explanations, particularly since they don’t really affect the basic situation. As a matter of fact, I never completely understood the final explanation.

A.H. Well, the explanation is that Rebecca wasn’t killed by her husband; she committed suicide because she had cancer.

F.T. Well, I understood that, because it’s specifically stated, but what I’m not too clear about is whether the husband himself believes that he is guilty.

A.H. No, he doesn’t.

F.T. I see. Was the adaptation faithful to the novel?

A.H. Yes, it follows the novel very faithfully because Selznick had just made Gone with the Wind. He had a theory that people who had read the novel would have been very upset if it had been changed on the screen, and he felt this dictum should also apply to Rebecca. You probably know the story of the two goats who are eating up cans containing the reels of a film taken from a best seller. And one goat says to the other, “Personally, I prefer the book!”

F.T. There are many variations to that story. I must say that even today, twenty-six years after it was made, Rebecca is still very modern, very solid.

A.H. Yes, it has stood up quite well over the years. I don’t know why.

F.T. Making that picture, I imagine, was something of a challenge. After all, the novel itself was a rather unlikely one for you; it wasn’t a thriller, there was no suspense. It was simply a psychological story, into which you deliberately introduced the element of suspense around the conflict of personalities. The experience, I think, had repercussions on the films that came later. Didn’t it inspire you to enrich many of them with the psychological ingredients you initially discovered in the Daphne du Maurier novel?

A.H. That’s true.

F.T. The relationship of the heroine, for instance . . . By the way, what was her name?

A.H. She never had a name.

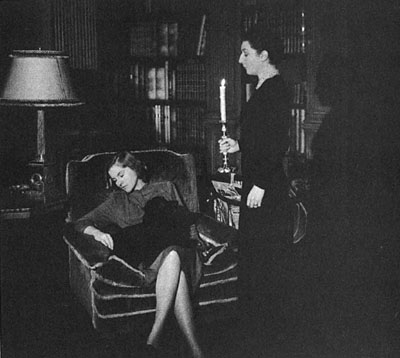

F.T. . . . anyway, her relationship with the housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, was something new in your work. And it reappears time and again later on, not only in the scenarios, but even visually: two faces, one dead-still, as if petrified by fear of the other; the victim and the tormentor framed in the same image.

A.H. Precisely. In Rebecca I did that very deliberately. Mrs. Danvers was almost never seen walking and was rarely shown in motion. If she entered a room in which the heroine was, what happened is that the girl suddenly heard a sound and there was the ever-present Mrs. Danvers, standing perfectly still by her side. In this way the whole situation was projected from the heroine’s point of view; she never knew when Mrs. Danvers might turn up, and this, in itself, was terrifying. To have shown Mrs. Danvers walking about would have been to humanize her.

F.T. It’s an interesting approach that is sometimes used in animated cartoons. Incidentally, you’ve said that the picture is lacking in humor, but my guess would be that you must have had some fun with the scenario because it’s actually the story of a girl who makes one blunder after another. Recently, I saw the picture again, and I couldn’t help imagining the working sessions between you and your scriptwriter: “Now, this is the scene of the meal. Shall we have her drop her fork or will she upset her glass? Let’s have her break the plate . . .” Anyway, that’s the impression I got.

A.H. That’s quite true; it did happen that way and we had a good deal of fun with it.

F.T. The characterization of the girl recalls the little boy in Sabotage. When she breaks a statuette, she furtively hides the pieces in a drawer, although she’s the mistress of the estate. Something else: Whenever that home is mentioned, it’s as the Manderley mansion or the estate. Whenever it is shown there is an aura of magic about it, with mists, and the musical score heightens that haunting impression.

A.H. That’s right, because in a sense the picture is the story of a house. The house was one of the three key characters of the picture.

F.T. It’s the first one of your pictures that evokes a fairy tale.

A.H. It is. It’s almost a period piece.

F.T. This fablelike quality is of interest because it recurs in several of your works. It is suggested by the emphasis on the keys to the house, by a closet that no one has the right to open, or by a room that is sealed off.

A.H. Yes, we were aware of that aspect in our treatment of Rebecca. It’s quite true that children’s fairy tales are often terrifying. Take the Grimms’ “Hansel and Gretel,” for instance, in which two children shove an old lady into an oven. But I’m not aware of any of my other pictures resembling a fairy tale.

F.T. Well, it’s probably because you’re dealing with fear that many of your pictures have that quality. Anything connected with fear takes us back to childhood. All of children’s literature is linked to sensations and particularly to fear.

A.H. You have a point, there. You may remember that the location of the house is never specified in a geographical sense; it’s completely isolated. That’s also true of the house in The Birds. I felt instinctively that the fear would be greater if the house was so isolated that the people in it would have no one to turn to.

In Rebecca the mansion is so far away from anything that you don’t even know what town it’s near. Now, it’s entirely possible that this abstraction, which you’ve described as American stylization, is partly accidental, and to some extent due to the fact that the picture was made in the United States. Let us assume that we’d made Rebecca in England. The house would not have been so isolated because we’d have been tempted to show the countryside and the lanes leading to the house. But if the scene had been more realistic, and the place of arrival geographically situated, we would have lost the sense of isolation.

F.T. Were the British critical about the American aspects of Rebecca?

A.H. No, they rather liked the picture.

F.T. What about the whole mansion, as shown from the outside. Was that a real house or a miniature?

A.H. We built a miniature. Even the road leading up to the home was a miniature.

F.T. Plastically speaking, the use of miniatures resembling old woodcuts idealized the film and further strengthened the fairy-tale quality. Actually, the story of Rebecca is quite close to “Cinderella.”

A.H. The heroine is Cinderella, and Mrs. Danvers is one of the ugly sisters. But it was even closer to Pinero’s His House in Order. That’s a play in which the villain isn’t the housekeeper but the sister of the master of the house; in other words, she’s Cinderella’s sister-in-law.

Hitchcock appears in Rebecca (1940), passing by the telephone booth being used by George Sanders.

F.T. The mechanism of Rebecca is remarkable. The sinister momentum is built up solely through references to a dead woman who is never shown. The picture won an Oscar, didn’t it?

A.H. Yes, the Academy voted it the best picture of the year.

F.T. I believe that’s the only Oscar you’ve ever won.

A.H. I’ve never received an Oscar.

F.T. But you just said that Rebeccu . . .

A.H. The award went to Selznick, the producer. The directing award that year was given to John Ford for The Grapes of Wrath.

F.T. Let’s get back to the American film scene. One of the more unfortunate aspects of Hollywood is that film-making is arbitrarily separated into distinct classifications. There are the directors who make what are rated as “A” pictures and the others who make the “B” and “C” films. And short of a sensational hit, it appears to be very difficult to switch from one category to another.

A.H. That’s right. They stay on one line all the time.

F.T. The point I’m getting at is this: I am rather surprised that after an outstandingly successful picture like Rebecca you would go on to make Foreign Correspondent. Though I admire the picture very much, it definitely belongs in the “B” category.

A.H. I can explain that quite easily. Here again, the problem is the casting. In Europe, you see, the thriller, the adventure story is not looked down upon. As a matter of fact, that form of writing is highly respected in England, whereas in America it’s definitely regarded as second-rate literature; the approach to the mystery genre is entirely different. When I had completed the script of Foreign Correspondent, I went to Gary Cooper with it, but because it was a thriller, he turned it down. This attitude was so commonplace when I started to work in Hollywood that I always ended up with the next best—in this instance, with Joel McCrea. Many years later Gary Cooper said to me, “That was a mistake. I should have done it.”

F.T. Walter Wanger was the producer of that picture. Did he choose the story?

A.H. Yes. He had always been interested in foreign politics, and he had a book called Personal History, written by Vincent Sheean, a very famous foreign correspondent. But the book was a straight autobiographical account; there was no story, no adventure; there was nothing we could use pictorially. So it became an original screenplay by Charles Bennett and myself.

F.T. The story, as I recall it, went something like this: Joel McCrea, an American newspaperman, is assigned to go over to Europe at the beginning of 1939 to assess the threatened outbreak of a world conflict. In London he meets an elderly Dutch diplomat who is carrying a secret Allied treaty back to his country. When the Nazis kidnap the Dutch diplomat, the hero goes to Holland to try and find him. Laraine Day plays the young English girl who helps him on his rescue mission, and Herbert Marshall plays her father, a member of the British upper class who masquerades as the head of an international pacifist organization, but is, in reality, an agent of the Nazis.

On the day war is declared, the father, who is about to be exposed, manages to get on a plane leaving for America. Joel McCrea and Laraine Day, having completed their mission, are also on the plane. When the Germans attack, the plane crashes into the sea and the father sacrifices himself to save his daughter. The young couple make their way back to London, where the hero resumes his duties with a dramatic broadcast to America about the war that has just begun. So much for the story.

A.H. As you see, it’s in line with my earlier films, the old theme of the innocent bystander who becomes involved in an intrigue.

F.T. I imagine you were not particularly keen on the choice of Laraine Day as your leading lady.

A.H. I would have liked to have bigger star names.

F.T. But Joel McCrea was likable in the role.

A.H. Yes, except that he was too easygoing.

There were lots of ideas in that picture, though.

F.T. There certainly were. One of them is the windmill scene, which, I understand, was your point of departure for the whole film. Your idea was to show that wings spinning against the direction of the wind might be used to convey a secret message to the planes above.

A.H. Yes, we started out with the idea of the windmill sequence and also the scene of the murderer escaping through the bobbing umbrellas. We were in Holland and so we used windmills and rain.

Had the picture been done in color, I would have worked in a shot I’ve always dreamed of: a murder in a tulip field. Two characters: the killer, a Jack-the-Ripper type, behind the girl, his victim. As his shadow creeps up on her, she turns and screams. Immediately, we pan down to the struggling feet in the tulip field. We would dolly the camera up to and right into one of the tulips, with the sounds of the struggle in the background. One petal fills the screen, and suddenly a drop of blood splashes all over it. And that would be the end of the killing.

In Foreign Correspondent there’s one shot so unusual that it’s rather surprising that the technicians never bothered to question how it was done. That’s when the plane is diving down toward the sea because its engines are crippled. The camera is inside the cabin, above the shoulders of the two pilots who are trying to pull the plane out of the dive. Between them, through the glass cabin window, we can see the ocean coming closer. And then, without a cut, the plane hits the ocean and the water rushes in, drowning the two men. That whole thing was done in a single shot, without a cut!

F.T. I suppose the way you did it was to combine some transparencies with streams of real water.

A.H. I had a transparency screen made of paper, and behind that screen, a water tank. The plane dived, and as soon as the water got close to it, I pressed the button and the water burst through, tearing the screen away. The volume was so great that you never saw the screen.

A little later on there was another tricky shot. Just before the plane sank, we wanted to show one of the wings, with people on it, breaking away from the body of the plane. At the bottom of a large water tank, we installed some rails and we put the airplane on those rails. And we had a branch rail, like on the railways, so that when the wing broke away, it moved off on that branch track. It was all quite elaborate, but we had lots of fun doing it.

A.H. A lot of the material for that picture was shot by a second unit on location in London and in Amsterdam. This was in 1940, you see, and the cameraman who went over the first time from London to Amsterdam was torpedoed and lost all his equipment. He had to go over a second time.

F.T. It’s been said that Dr. Goebbels enjoyed Foreign Correspondent very much.

Van Meer (Albert Basserman), held prisoner, is questioned by the spy Stephen Fisher (Herbert Marshall), whom he thinks is his friend. At the left is Eduardo Cianelli as Krug. The sympathetic ffolliott, played by George Sanders, has just arrived in time to prevent old Van Meer from revealing the famous secret clause, but a hand holding a revolver is enough to turn the situation around.

A.H. Yes, I heard that too; it’s possible that he got a print of the film through Switzerland. The picture was pure fantasy, and, as you know, in my fantasies, plausibility is not allowed to rear its ugly head. In Foreign Correspondent you have the masculine counterpart of the old lady of The Lady Vanishes. Here the secret is in the possession of an elderly gentleman.

F.T. You mean Mr. Van Meer, the man who knows the famous secret clause?

A.H. That secret clause was our “MacGuffin.” I must tell you what that means.

F.T. Isn’t the MacGuffin the pretext for the plot?

A.H. Well, it’s the device, the gimmick, if you will, or the papers the spies are after. I’ll tell you about it. Most of Kipling’s stories, as you know, were set in India, and they dealt with the fighting between the natives and the British forces on the Afghanistan border. Many of them were spy stories, and they were concerned with the efforts to steal the secret plans out of a fortress. The theft of secret documents was the original MacGuffin. So the “MacGuffin” is the term we use to cover all that sort of thing: to steal plans or documents, or discover a secret, it doesn’t matter what it is. And the logicians are wrong in trying to figure out the truth of a MacGuffin, since it’s beside the point. The only thing that really matters is that in the picture the plans, documents, or secrets must seem to be of vital importance to the characters. To me, the narrator, they’re of no importance whatever.

You may be wondering where the term originated. It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men in a train. One man says, “What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?”

And the other answers, “Oh, that’s a MacGuffin.”

The first one asks, “What’s a MacGuffin?”

“Well,” the other man says, “it’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.”

The first man says, “But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,” and the other one answers, “Well then, that’s no MacGuffin!” So you see that a MacGuffin is actually nothing at all.

F.T. That’s funny. A fascinating idea.

A.H. Another funny thing is that whenever I’m working with a writer who’s never been on a Hitchcock project before, he invariably becomes obsessed with the MacGuffin. And, though I keep on explaining that it’s not important, the most elaborate schemes are mapped out. For instance in The Thirty-nine Steps, what are the spies after? The man with the missing finger? And that woman at the beginning, was she on to some big secret? Is it because she was getting close to the truth that it became necessary to stab her in the back?

In the early stages of the construction, we felt, and we were all wrong, that since life and death were involved, the pretext had to be a very important one. In our first draft, when Robert Donat arrives in Scotland, he picks up some additional information on his way to the spy’s house, possibly by following the spy. He rides to the top of the hill, and looking down, he sees underground plane hangars carved into the side of the mountain, secret hangars, which made the planes safe from bombings. Our original idea was that this MacGuffin should be something big and pictorially striking. Then we went on to work it out in our minds: What does Donat do upon discovering these secret hangars? Will he send off a message to report their locations? And in that case, what counter-steps would the spies take?

F.T. Well, the only way to work that out in the script was to have them blow up the hangars.

A.H. We thought of that. But how were we going to have them blow up a whole mountain? Anyway, whenever we found ourselves getting terribly involved in this way, we would drop the idea for something very simple.

F.T. In other words, not only is there no need for the MacGuffin to be important or serious, but it’s even preferable that it should turn out to be something as trivial and absurd as the little tune of The Lady Vanishes.

A.H. Exactly. In The Thirty-nine Steps the MacGuffin turned out to be the mechanical formula for the construction of an airplane engine. Instead of putting it down on paper, the spies used Mr. Memory’s brain to carry it out of the country.

F.T. If I understand you correctly, whenever a person’s life is at stake, the dramatic rule is that concern for his survival must become so intense that, as the action moves forward, the MacGuffin will pretty much be forgotten. But this approach, it seems to me, involves a certain risk, doesn’t it? In many films the audience will hiss and jeer at the final explanation, the scene in which the so-called MacGuffin is revealed. But I’ve noticed that one of your tricks is to dispose of the MacGuffin, not at the end of the picture, but at some point midway in the story, so that there’s no need to condense the whole exposé into the finale.

A.H. On the whole, that’s correct, but the main thing I’ve learned over the years is that the MacGuffin is nothing. I’m convinced of this, but I find it very difficult to prove it to others. My best MacGuffin, and by that I mean the emptiest, the most nonexistent, and the most absurd, is the one we used in North by Northwest. The picture is about espionage, and the only question that’s raised in the story is to find out what the spies are after. Well, during the scene at the Chicago airport, the Central Intelligence man explains the whole situation to Cary Grant, and Grant, referring to the James Mason character, asks, “What does he do?” The counterintelligence man replies, “Let’s just say that he’s an importer and exporter.”

“But what does he sell?”

“Oh, just government secrets!” is the answer.

Here, you see, the MacGuffin has been boiled down to its purest expression: nothing at all!

F.T. That’s right, nothing that is specific.

Anyway, all of this clearly shows that you’re always fully aware of your intention, and that everything you do is carefully thought out. And yet, these pictures, hinged around a MacGuffin, are the very ones that some of the critics have in mind when they claim that “Hitchcock’s got nothing to say.” The only answer to that is that a film-maker isn’t supposed to say things; his job is to show them.

A.H. Precisely.

F.T. Right after Foreign Correspondent, in 1941, you went on to make a picture that’s rather out of line with the rest of your works, since it’s your only American comedy. Mr. and Mrs. Smith is the classic story about a divorced couple who seem to run into each other after their separation, engage in a certain amount of competition and wind up getting together again.

Robert Montgomery and Carole Lombard in Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941).

A.H. That picture was done as a friendly gesture to Carole Lombard. At the time, she was married to Clark Gable, and she asked whether I’d do a picture with her. In a weak moment I accepted, and I more or less followed Norman Krasna’s screenplay. Since I really didn’t understand the type of people who were portrayed in the film, all I did was to photograph the scenes as written.

There’s an amusing little sidelight on that picture. A few years prior to my arrival in Hollywood, I had been quoted as saying that all actors are cattle. I’m not quite sure in what context I might have made such a statement. It may have been made in the early days of the talkies in England, when we used actors who were simultaneously performing in stage plays. When they had a matinee, they’d leave the set, I felt, much too early for a matinee, and I suspected they were allowing themselves plenty of time for a very leisurely lunch. And this meant that we had to shoot our scenes at breakneck speed so that the actors could get out on time. I couldn’t help feeling that if they’d been really conscientious, they’d have swallowed their sandwich in the cab, on the way to the theater, and get there in time to put on their make-up and go on stage. I had no use for that kind of actor. Another reason for resentment is that I’d sometimes overhear two actresses talking in a restaurant. One would say to the other, “What are you doing now, dear?” and the other one would say, “Oh, I’m filming,” in the same tone of voice as if she were saying, “Oh, I’m slumming.”

And this raises a grievance I have against those people who come into our industry by way of the theater or as writers and who work in our medium for the money only. I think the worst culprits are the writers, particularly those who are here in Hollywood. Authors come in from New York, get a contract from M-G-M with no specific assignment, and then they say, “What do you want me to write?” Some playwrights sign three-month contracts just in order to spend their winters in California. By the way, how did we get on to this subject?

F.T. We were talking about your statement that “actors are cattle.”

A.H. Oh yes. Well, what I was leading up to is that when I arrived on the set, the first day of shooting, Carole Lombard had had a corral built, with three sections, and in each one there was a live young cow. Round the neck of each of them there was a white disk tied on with a ribbon, with three names: Carole Lombard, Robert Montgomery, and the name of a third member of the cast, Gene Raymond. I should add that my comment was a generalization, and Carole Lombard’s spectacular repartee was her way of kidding me. She probably agreed with me.

F.T. This brings us to Suspicion, and you might cover a point we skipped. In our talks about Rebecca I forgot to ask your opinion of Joan Fontaine. I believe she was an important actress to you.

A.H. Well, in the preparatory stages of Rebecca, Selznick insisted on testing every woman in town, known or unknown, for the lead in the picture. I think he really was trying to repeat the same publicity stunt he pulled in the search for Scarlett O’Hara.

He talked all the big stars in town into doing tests for Rebecca. I found it a little embarrassing, myself, testing women who I knew in advance were unsuitable for the part. All the more so since the earlier tests of Joan Fontaine had convinced me that she was the nearest one to our heroine. In the early stages of the actual shooting, I felt that Joan Fontaine was a little self-conscious, but I could see her potential for restrained acting and I felt she could play the character in a quiet, shy manner. At the outset she tended to overdo the shyness, but I felt she would work out all right, and once we got going, she did.

F.T. In the sense of her physical frailty, she’s quite unlike Ingrid Bergman and Grace Kelly.

A.H. I think so, too. You might say Suspicion was the second English picture I made in Hollywood: the actors, the atmosphere, and the novel on which it’s based were all British. The screenwriter was Samson Raphaelson, who’d worked on the early talking pictures of Ernst Lubitsch.

F.T. And with him, the family brain trust, Alma Reville and Joan Harrison.

A.H. The original novel was Before the Fact, and the author’s—Francis lies’—real name was A. B. Cox. He sometimes also wrote under the pen name of Anthony Berkeley. I’ve often wanted to film his first novel, Malice Aforethought. The book opens with the sentence: “It was not until several weeks after he had decided to murder his wife that Dr. Bickleigh took any active steps in the matter.” The reason I didn’t do it is that it requires a mature man in the part. It’s hard to find the right actor, perhaps Alec Guinness . . .

F.T. Would you do it with James Stewart?

A.H. James Stewart would never play a killer.

F.T. Some of the critics who’d read Before the Fact reproach you with having changed the whole thing. The novel is the story of a woman who gradually realizes that she’s married a murderer and is so much in love that she finally allows herself to be killed by him. Your picture is about a woman who, upon discovering that her husband is indifferent, a liar, and a spendthrift to boot, begins to imagine he’s a killer as well, and suspects him—though, in fact, subsequent events will prove she’s wrong—of wanting to murder her.

In our discussions about The Lodger, you referred to Suspicion and said that the producers would have objected to Cary Grant being the killer. If I understood you correctly, you’d have preferred that he be the guilty one.

A.H. Well, I’m not too pleased with the way Suspicion ends. I had something else in mind. The scene I wanted, but it was never shot, was for Cary Grant to bring her a glass of milk that’s been poisoned and Joan Fontaine has just finished a letter to her mother: “Dear Mother, I’m desperately in love with him, but I don’t want to live because he’s a killer. Though I’d rather die, I think society should be protected from him.” Then, Cary Grant comes in with the fatal glass and she says, “Will you mail this letter to Mother for me, dear?” She drinks the milk and dies. Fade out and fade in on one short shot: Cary Grant, whistling cheerfully, walks over to the mailbox and pops the letter in.

F.T. That would have been a great twist. I’ve read the novel and I liked it, but the screenplay’s just as good. It is not a compromise; it’s actually a different story. The film version, showing a woman who believes her husband is a killer, is less farfetched than the novel, which is about a woman who accepts the fact that her husband is a murderer. It seems to me that the film, in terms of its psychological values, has an edge over the novel because it allows for subtler nuances in the characterizations.

One might even say that Hollywood’s unwritten laws and taboos helped to purify Suspicion by dedramatizing it, in contrast with routine screen adaptations, which tend to magnify the melodramatic elements. I’m not saying that the picture is superior to the novel, but I do feel that a novel that followed the story line of your screenplay might have made a better book than Before the Fact.

A.H. That may or may not be; I can’t say, but I do know that I ran into lots of difficulties on that picture. When it was finished, I spent two weeks in New York, and I had quite a shock when I came back. One of RKO’s producers had screened the picture, and he found that many of the scenes gave the impression that Cary Grant was a killer. So he simply went ahead and ordered that all of these indications be deleted; the cut version only ran fifty-five minutes. Fortunately, the head of RKO realized that the result was ludicrous, and they allowed me to put the whole thing back together again.

F.T. Aside from that, are you satisfied with Suspicion?

A.H. Up to a point. The elegant sitting rooms, the grand staircases, the lavish bedrooms, and so forth, those were the elements that displeased me. We came up against the same problem we had with Rebecca, an English setting laid in America. For a story of that kind, I wanted authentic location shots. Another weakness is that the photography was too glossy. By the way, did you like the scene with the glass of milk?

F.T. When Cary Grant takes it upstairs? Yes, it was very good.

A.H. I put a light in the milk.

F.T. You mean a spotlight on it?

A.H. No, I put a light right inside the glass because I wanted it to be luminous. Cary Grant’s walking up the stairs and everyone’s attention had to be focused on that glass.

F.T. Well, that’s just the way it worked out. It was a very effective touch.

Joan Fontaine thinks her husband is a murderer.