At the end of the nineteenth century, spying was the business of gentlemen. It was, in a sense, conducted in the open. And because the governments of Europe had only small agencies to gather political and military information about their enemies and would-be enemies, much of the intelligence was gathered in an informal way by individuals who were not working for any intelligence agency. For example, visitors to a port city would amble about, all the while noticing what was being shipped, how much was being shipped, and where it was going. Military attachés in cities like Berlin, Vienna, and Stockholm gathered military intelligence in the country in which they were posted. They would, for instance, watch for troop redeployment or changes in training schedules. As one British attaché put it, “Certainly [an agent] must keep his eyes and ears open and miss nothing, but secret service is not his business.” It soon became his business.

With European nations spying and counterspying as their countries edged closer to war, President Woodrow Wilson kept the United States on a course of neutrality. He didn’t want the nation involved in any activities, including espionage, that might imply that the U.S. was taking sides in the growing tension. In one of the ironies of World War I, the entry of the United States into a war in Europe started in Mexico. President Wilson had long been uneasy about the unstable political situation in Mexico. In 1911 things took a turn for the worse when Porfirio Díaz, Wilson’s choice as leader of Mexico, was overthrown by Francisco Madero. Madero was then overthrown by General Victoriano Huerta in 1913. To make matters horribly worse, Huerta ordered the murder of Madero and his vice president.

Outraged by such treachery, Wilson refused to recognize the Huerta government. Things turned against the Huerta regime when two insurgents threatened his leadership: General Venustiano Carranza and Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Despite the fact that Wilson supplied Villa with arms — a questionable move by a president with a noninterventionist policy — Villa and his men were unable to overthrow Huerta.

Because the United States was receiving almost no intelligence from field agents about the situation in Mexico, President Wilson could only wait for events to unfold and then react to them. Faced with a situation that had the potential to sweep across the unprotected two-thousand-mile border between the two countries, Wilson did nothing to authorize an intelligence agency to gather information that could benefit the United States.

To make matters worse, Villa used the arms that the United States had given to him against American citizens. On January 10, 1916, Villa and his small band of rebels stopped a train near Santa Ysabel in Mexico and kidnapped then murdered eighteen young American mining engineers. Two months later, Villa and an army of about five hundred men rode into Columbus, New Mexico, and shot up the town, killing fifteen Americans and wounding many others. Wilson was finally driven to action, ordering Brigadier General John “Black Jack” Pershing and a contingent of U.S. troops over the border into Mexico. But Pershing could not count on having any consistent and reliable intelligence, particularly from local citizens.

Many historians consider 1915 to be the low point of American military intelligence. That was the year that intelligence work came to a halt in the General Staff’s War College Division. The timing could not have been worse for the U.S. Not only was the country facing problems with Villa, but Germany was also about to begin making overtures to Mexico about playing a part in Germany’s plans for victory in the war. Still, the U.S. did nothing to improve intelligence gathering.

“Black Jack” Pershing was not about to wait for the government to debate the issue of intelligence. He moved quickly and resolutely to fill the intelligence void in which he was expected to operate by creating his own spy operation. Cavalry Major James A. Ryan was in charge of the operation for a short time before turning over command to Captain W. O. Reed, who increased the number of operatives to provide intelligence on Pancho Villa. Reed added twenty Apache scouts to his operations.

Japanese-American relations had, meanwhile, been strained for some time over U.S. immigration policies. A 1905 peace treaty brokered by President Theodore Roosevelt had failed to completely satisfy the Japanese, and although the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907–1908 eased the situation, Roosevelt remained wary.

Roosevelt’s misgivings seemed to be validated in 1911 when it was rumored that Japan had sent representatives to discuss the possibility of establishing a base on Magdalena Bay, on Mexico’s west coast. There were even signs that a large number of Japanese soldiers had conducted training operations in the Sonoran Desert, to the north of the Gulf of California. It was believed that some of those soldiers had crossed the border into California. But, once again, the United States did not have the intelligence capacity to discover such operations before they were carried out.

Faced with the pressing needs for information on these two fronts, then — the hunt for Pancho Villa and threats from the Japanese — as well as a significant German presence in Mexico, Wilson finally (and grudgingly) agreed to allow a spy operation in Mexico. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) hired operatives in Mexico to report on activities involving both Japanese and German representatives. To bolster this meager operation, the ONI also solicited volunteer spies from some of the large U.S. corporations operating in Latin America, including Standard Oil and United Fruit. With so much at stake, these companies were eager to help. Although this effort improved the situation, Pershing and his team never were able to run Villa down.

Germany’s covert operations in Mexico had so far been limited to the political arena, mostly connected with propaganda. Berlin secretly subsidized a handful of Mexican newspapers to serve as outlets for propaganda operations. At the same time, Carranza’s government was actively courting Germany in the hope of building a closer economic and military relationship with Berlin. The German foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, did everything he could to nurture such a relationship with a country bordering the United States, hoping that with the inducement of trade and arms, Carranza would engage the U.S. in conflicts that would require troops and supplies, forcing America to focus its attention and military funding south of the border rather than in Europe.

Getting Mexico into position to engage the United States remained high on the list of German covert operations in the Western Hemisphere. Living in exile, President Huerta was more than willing to draw the U.S. into war. In return Huerta wanted money from the Germans to buy arms and munitions, which he wanted delivered by German submarines. He also wanted reassurance that Berlin would stand behind him if needed.

When Huerta was arrested by U.S. agents on June 25, 1915, the Germans decided to change tactics and bring their espionage operations across the border into the U.S. By this time, it was clear to Berlin that the war was not going to be short and swift, as they had expected. Further, if they wanted to win the war, they needed to make certain that the U.S. stayed out of it. They also wanted to put a choke hold on the flood of arms and other war supplies from U.S. ports to England. To reach that goal, Walther Nicolai, cunning German spymaster, created an espionage plan for his operatives in the United States that would make use of political, psychological, economic, and paramilitary strategies.

To begin their campaign of psychological and political dirty tricks, Berlin hired an American public relations man, William Bayard Hale, to serve as their propagandist. In addition to inserting pro-German articles in American city newspapers, Berlin funded The Fatherland, a weekly newspaper in the U.S. Berlin also purchased the Mail and Express, an established New York City newspaper, as another outlet for their propaganda.

In addition to out-and-out blatant propaganda, the newspapers published features that were aimed at Americans who were not necessarily pro-German but who could be counted on for help. For example, they tried to appeal to the Irish, with their strong anti-British attitude. Germany also tried to attract isolationists and pacifists, who felt the United States should not meddle in the affairs of sovereign European nations. The Germans were hoping to ignite a grassroots movement that would forcefully protest any American involvement in the war, including sending arms or troops.

The German Information Service (GIS) was what is known as a white propaganda agency. Such white groups operated within the limits of the law as they tried to derail any efforts of the U.S. government to enter the war. The GIS published a daily list of pro-German editorials and articles that would attract the attention of resident German aliens as well as German Americans.

The most direct attempt by Germany to curtail the production of war supplies was its creation of the Bridgeport Projectile Company (BPC). In the language of the espionage establishment, BPC was a proprietary company, a front for their efforts to limit munitions that could be sent to the Allies. They ordered huge quantities of materials deemed essential to fight the war. For example, BPC placed orders for machine tools and hydraulic presses, thus making them unavailable for legitimate companies that needed such parts to produce war supplies. BPC also ordered five million pounds of gunpowder from Aetna Powder Company, an order so large that Aetna could sell no powder to the U.S. government.

Merely ordering the parts created a shortage of machine parts that slowed down production of wartime necessities. German agents likewise tried to corner the market on chlorine, a poisonous gas that killed uncountable soldiers in the trenches on both sides. The Bridgeport Projectile Company offered inflated wages, thereby causing unrest among workers at other munitions plants. It gladly paid higher wages as part of its plan to upset manufacture of munitions by the United States. BPC did not necessarily even need to produce munitions that could be shipped to Germany. They only needed to keep war materials out of the hands of U.S. manufacturers. Any materials that were delivered were simply stored at the Bridgeport facility. Some were eventually destroyed.

If Berlin hoped to sustain their enormously successful covert operations for an indefinite period of time, those hopes vanished because of a colossal blunder by one of their own, Dr. Heinrich Albert, a German commercial attaché and finance officer for the German espionage operation in the United States. As finance officer, he was responsible for paying operatives in this country. He chose the wrong time to become forgetful, and U.S. agents were there to take advantage of his error.

William G. McAdoo, secretary of the treasury, authorized a covert operation, assigning Secret Service agents to follow several German and Austro-Hungarian attachés who were under suspicion of espionage. On July 24, 1915, the surveillance team of Special Agents William Houghton and Frank Burke followed George Sylvester Viereck, editor of The Fatherland, and Dr. Heinrich Albert, when they left Albert’s office in New York. The men boarded a Sixth Avenue elevated train, Houghton and Burke right behind them. Viereck got off the train at Twenty-third Street, with Houghton tailing him.

From his seat right behind the attaché, Agent Burke studied Albert. A heavyset man, measuring about six feet tall, he bore crosscut saber scars on his right cheek. Burke also noted a briefcase beside the German. Albert opened a newspaper and was soon caught up in the news of the day before he nodded off. Startled by the sudden arrival at his station at Fiftieth Street, Albert bolted from his seat and hurried off the train. Burke knew he didn’t need to follow Albert any longer when he noticed that Albert had left his briefcase behind. A woman passenger called out to Albert, pointing to his briefcase. But before Albert could reenter the train, Agent Burke snatched the briefcase. As Albert pushed his way back into the car, Burke dashed out the other door of the car, with Albert close behind him. The chase was on until Burke leaped onto a streetcar. He told the conductor that the madman following him had caused a ruckus at the train station. The conductor took one look at Albert, running down the street, wildly waving his arms, and told the motorman not to stop at the next corner. The streetcar moved on, leaving Albert behind.

The briefcase was jammed with telegrams from Berlin, communication for Albert’s spies and agents, and financial records. When Secretary McAdoo read the translated documents, he was astounded to learn about the workings of the Bridgeport Projectile Company and the German financing of The Fatherland. But he also realized that, as underhanded as the covert actions of the German agents were, he could see no federal law that had been violated. With the prospect of arrest and legal action against these agents improbable, McAdoo was determined to expose the treachery of German agents on U.S. soil in a way that would still put the agents out of business: publicity.

McAdoo handed the documents over to the editor of the New York World. The headlines of the next edition screamed the news across page one: “How Germany Has Worked in the U.S. to Shape Opinion, Block the Allies, and Get Munitions for Herself Told in Secret Agent’s Letters.” Included in the front-page article, which nearly filled the entire page, were documents and a reproduction of two letters. Germany’s secrets were revealed for all Americans to read.

Count Johann von Bernstorff, German ambassador to the United States, later called the affair “merely a storm in a teacup,” pointing out that there was no evidence to show that any law had been broken. True enough, but, as one historian observed, the publicity not only neutralized the “huge and expensive” covert psychological operation; it was also “made to backfire, dealing a devastating blow” to Germany. And, as Captain Franz von Papen, German military attaché in Mexico City, later admitted, “Our contracts [for war materials] were challenged, cancelled, or replaced by other ‘priority’ orders, and our scheme came to an end.” American munitions manufacturers were no longer wasting time and material filling phony orders for Germany. These supplies could now be used for legitimate U.S. orders.

While the U.S. intelligence community could feel justifiable satisfaction in rolling up the German psychological and propaganda machine, they were not nearly as successful in preventing the sabotage operations carried out by German agents in the United States. German saboteurs targeted many plants, mostly in the northeast, that manufactured arms, munitions, and other supplies for the Allies. That the efforts of German agents were so successful is an indication of how the U.S. counterintelligence community was woefully unprepared.

On November 11, 1914, the German General Staff approved “hiring destructive agents among agents of anarchist organizations.” About two weeks later, the German Intelligence Bureau of the High Sea Fleet General Staff put forth a similar order for all “destruction agents” to “mobilize immediately.” The General Staff was especially keen on agents in or near commercial operations and military bases “where munitions are being loaded on ships going to England, France, Canada, the United States of North America and Russia.”

With orders issued, it wasn’t long before American plants and facilities were targeted. On New Year’s Day, a destructive fire of suspicious but unknown origin burned out a plant that manufactured wire cable in Trenton, New Jersey. Two days later, an explosion rocked the SS Orton, anchored in the Erie Basin in Brooklyn, New York. Other fires and explosions ripped through a number of New Jersey plants that produced weapons or gunpowder. In April a ship carrying arms caught fire at sea. Bombs were found on two others. But the worst was yet to come.

The German consul in San Francisco, Franz von Bopp, ordered that time bombs be hidden on four ships at anchor in Tacoma, Washington. Filled with gunpowder and destined for Russia, the ships were a prime target. The saboteurs did their work well. Explosions rocked Tacoma and nearby Seattle, destroying all the powder. The U.S. still had no counterintelligence system that might have alerted them to such bomb-making operations.

Two of the men who took part in the Tacoma sabotage, Kurt Jahnke and Lothar Witzke, were sent east by von Bopp to work with a sabotage ring that was operating in the New York City–New Jersey area. The men had hoped to plant bombs along the way on trains carrying thousands of horses and mules east for shipment to Europe. An alternative to this plan was to infect the animals with anthrax cultures and an infectious disease called glanders. Fortunately, neither plan was carried out.

The spring and summer of 1915 was a busy time for saboteurs, including Jahnke and Witzke. Eight arms ships caught fire at sea. Bombs were discovered on another five ships. In addition, explosions and fire destroyed arms and powder plants in Wallington, Carney’s Point (three times), and Pompton Lakes, New Jersey. The operatives also scored hits at similar plants in Wilmington, Delaware (twice); Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Acton, Massachusetts. An arms train was wrecked in New Jersey.

Despite the success of the saboteurs, the German High Command was not satisfied with the work of their spy and sabotage operations. To direct what they hoped would be more destructive results, they sent Captain Franz von Rintelen, a junior member of the admiralty, to New York in 1915. His orders were clear. He was expected to do more to curtail the tons of war supplies, especially munitions, that were bound to Allied soldiers. Such supplies, Berlin believed, were prolonging the war. Von Rintelen felt confident that he would succeed. As he put it, “I’ll buy up what I can and blow up what I can’t.”

Realizing that so much of the war supplies passed through New York Harbor from docks and warehouses in Manhattan and New Jersey, von Rintelen decided that his base of operations should be there. Why travel the country looking for munitions factories to blow up, he reasoned, when his band of operatives could focus on the shipping in New York Harbor and, in a sense, have the munitions come to them?

Von Rintelen promptly converted one of the German merchant ships quarantined in New York Harbor into a bomb factory. He enlisted the help of Dr. Walter T. Scheele, a German chemist, who’d been in the country for a long time (such a person is called a sleeper agent) and Charles Schmidt, the chief engineer of the ship. Together they designed a device that would wreak havoc on munitions ships on the high seas. The bomb-making teacher began by cutting tubing into pieces seven inches or so long, about the size of a large cigar, then dividing the “cigar” into two watertight chambers, separated by a thin copper disk. The cigar bombs were then moved to Dr. Scheele’s laboratory in Hoboken, New Jersey, where he filled one chamber with sulfuric acid, the other with the highly explosive picric acid. The copper disk that separated the two acids needed to withstand the caustic effects of the acid for a sufficient period of time to allow the ship on which it was hidden to move out of the harbor and begin steaming toward England.

When a ship carrying Dr. Scheele’s “cigars” was on the high seas, the copper disk would corrode, allowing the acid in both chambers to mix, igniting a fire that was intense enough to melt the wax plugs on each end of the cigar. When the wax plugs melted, the fire received more oxygen, allowing it to burn more fiercely. Left undetected in a ship’s cargo hold, the fire would quickly spread, often destroying the cargo and even the ship itself. Before too long, the bomb factory was producing as many as fifty “cigars” each day. Von Rintelen set up similar bomb factories in the U.S. port cities of Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans.

Von Rintelen’s first success was aboard the SS Phoebus, which was hauling artillery shells to Russia. The cigars did their work, causing a fire that was discovered before it had destroyed all the shells. However, to put out the flames, the captain flooded the hold, turning the shells into useless hunks of metal. About half the ships with the hidden firebombs, sometimes as many as thirty “cigars,” made it safely to port, more than likely because the bombs failed to ignite. Nonetheless, the string of mysterious cargo fires aboard U.S. ships continued through the spring.

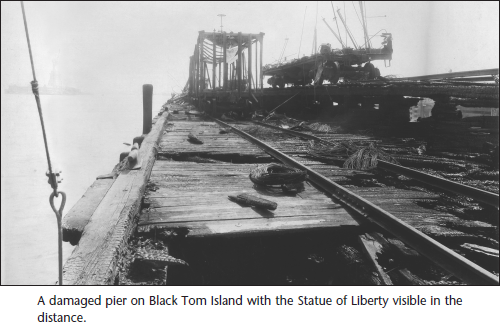

With the success of von Rintelen’s sabotage operations at a new high — the U.S. government had been unable to detect or infiltrate the spy rings — he was ready for a bigger challenge, and it didn’t take him long to find it. He would go after the Lehigh Valley Railroad Company’s huge terminal located on Black Tom Island, a point of land that juts out from Jersey City, New Jersey, across New York Harbor’s Upper Bay from Brooklyn, New York. The huge terminal was located at the southern end of what is today called Liberty State Park. It was, in fact, the busiest wartime port on the East Coast. Because federal law allowed munitions to be stored on Black Tom for only twenty-four hours, it was very busy. Ships of all sorts — tugs, barges, freighters — came and went all day. Inside the terminal, trains were in constant motion as they delivered war supplies — mostly munitions — then reversed direction to be refilled.

According to reports in the New York Times, there was plenty of fire power at the terminal on July 30: “11 [railroad] cars of high explosives, 17 of shells, 3 of nitro-allulos, 1 of TNT, and 2 of combination fuses; in all a total of 2,132,000 pounds of explosives.” In addition, “ten barges were tied up, most of them loaded with explosives,” which they’d taken on at other terminals and piers around New York Harbor.

The chain reaction of disaster began with a fire. One of the private detectives hired to guard the terminal remembered it this way: “The fire had started in the center of the string of cars on shore near the land end of the pier. The flames had gotten too good a start for us to do anything.” Of course, the shells soon began to “cook,” and shrapnel shells of smaller caliber began to explode. An investigation of the explosions found that an incendiary device — perhaps something like Dr. Scheele’s cigar bombs — had been hidden among the boxcars and probably on at least one of the munitions barges. Evidence indicated that the saboteurs had been paying off some of the terminal guards for intelligence about work schedules. Some investigators felt that the guards under suspicion likely looked the other way when the German agents arrived that night to do their damage.

The blasts were spectacular, rocking communities in New Jersey and New York. In fact, the tremor of the blast was felt as far away as Philadelphia, one hundred miles south. Windows shattered twenty-five miles from the blast. In Jersey City, a hunk of shrapnel rocketed into the clock tower of the Jersey Journal building, stopping the clock at exactly 2:13. The Statue of Liberty, on Bedloe’s Island, was only about 650 yards from Black Tom. The force of the explosion popped about a hundred of Lady Liberty’s rivets and her copper skin was pelted with shrapnel. (After inspection of the monument, no tourists were allowed in the torch.) The explosion also damaged Ellis Island, about a mile from the blast site. The high vaulted ceiling of the main hall collapsed, nearly every window shattered, and sections of the roof were damaged. All the while, of course, the sky was filled with a dangerous shower of shrapnel, shells, and burning debris.

Remarkably, when the fires were extinguished and people were accounted for, there were but seven fatalities in the explosions and inferno. This relatively low number of deaths is remarkable considering that almost five hundred people were aboard the ships tied up at the piers and anchored nearby. Scientists believe that the blast was about a 5.0 on the Richter scale. In comparison, the collapse of the World Trade Center north tower on September 11, 2001, registered a 2.3, according to a seismic observatory in New Jersey.

Initially investigations determined that the explosion and fire at Black Tom had been an accident exacerbated by carelessness of the owner of the facility. But further inquiry into the cause of the events of that July 30 led to two experienced saboteurs, Kurt Jahnke and Lothar Witzke. They had apparently teamed up with Michael Kristoff, described as a “mentally deficient Hungarian immigrant,” who lived and worked in the area. Jahnke and Witzke eased a small boat alongside one of the piers, where they met Kristoff and carried out their sabotage.

Although the catastrophe at Black Tom Island was by far the largest act of sabotage on American soil to that point, it was, according to the New York Times, one of fifty such acts of sabotage in the United States in the first two years of the war, from 1914 until the summer of 1916. Over half of the attacks (twenty-eight of fifty) took place in the New York–New Jersey area.

AFTER BENEDICT ARNOLD, there is probably no other name that people associate with spying more than that of Mata Hari. But, while Arnold’s reputation for spying and treachery is based on facts, Mata Hari’s seems to be more fiction than fact. Did she spy for France and Germany in World War I? She did. But her spying was minor in nature, rather than anything resembling the legendary feats and betrayal that are attributed to her.

The Dutch-born Margaretha Zelle began her career as an exotic dancer in Paris; her stage name, Mata Hari, derived from a Malay word meaning “sun” or “dawn.” For seven years she was a resounding success in many of the capitals of Europe, which gave her the opportunity to meet men of power. As she approached the age of forty, and the end of her dancing career, she developed “intricate, affectionate, and sometimes exclusive relationships, with men who supported her in elegant style.” Many of these men were involved in the highest levels of government and would readily share state or military secrets with her as a boastful sign of their importance.

Some historians believe that she met the German intelligence chief Walther Nicolai in 1916. The meeting was not an accidental encounter. Baron von Mirbach, an intelligence officer in Kleve, in western Germany, remembered seeing Mata Hari dance and felt she would make a good spy. Mirbach believed that German intelligence could take advantage of Mata Hari’s popularity with men who had access to information that might help the German war effort. Nicolai flattered her and put her up in a fancy Hamburg hotel, and she began her spy training. She was schooled on how to make meaningful observations, write reports in invisible ink, and send them to an address in Antwerp.

As it turned out, however, she wrote only a few letters, and they offered no significant intelligence, nothing more than rumors and bits of information that were generally well known. German intelligence decided that this amateur spy was a bigger liability than an asset and that she therefore had to be eliminated. But rather than do the deed themselves, they planned to maneuver the French into doing it for them.

To this end, they sent coded information about her to their agents in France, referring to her as agent H21, knowing that the code had already been broken by the French. The coded messages were, indeed, intercepted and read by French intelligence officers, sowing the seeds of doubt about Mata Hari in their minds. Was she a double agent working for France and Germany? Or had she simply turned and become a German agent?

Mata Hari returned to Paris to meet with Captain Georges Ladoux, chief of French military intelligence, and on February 13, 1917, Mata Hari was arrested and jailed in Saint Lazare prison, where her treatment was deplorable. She was forced to live in filthy conditions, isolated from other prisoners. She was not permitted to bathe, nor was she provided with a change of clothes. Prison officials allowed her fifteen minutes of physical exercise each day. Despite such horrible circumstances, Mata Hari maintained her innocence during her interrogation sessions, at one point writing a note to the investigator of her case, Pierre Bouchardon, that read, “You have made me suffer too much. I am completely mad. I beg you to put an end to this.”

At her trial, it was no surprise to anyone when she was unanimously condemned to death. As a final insult, she was first required to pay court costs. The firing squad assembled in the predawn hours of October 15, 1917.

In the final minutes of her life, Mata Hari faced the thirteen soldiers in the firing squad, her head held high. She refused the customary blindfold. Part of her legend includes the notion that she blew a kiss to the soldiers before shots cracked the morning stillness. Although it was clearly unnecessary, the officer drew his revolver and delivered the traditional coup de grâce, a single shot into the spy’s ear. With no one to claim the body, her remains were delivered to a medical school, for dissection by students.

Was Mata Hari a spy? Yes, but a far cry from being the “greatest woman spy” in history. It’s debatable if she was, in fact, a double agent. Some historians believe she spent fifteen weeks in a “spy academy,” learning the skills of the trade, including using various methods of coded communication, memorizing photographs and maps, and becoming familiar with weapons. Such training would have also included warnings about “fool spies,” or double agents. Mata Hari consistently told her interrogators that she never attended any such spy training sessions. Several biographers agree.

Even long after the war, the “little mysteries of counterespionage” prevented all the facts of Mata Hari’s case from being released. In fact, when Pierre Bouchardon published his memoir in 1953, he claimed that “professional secrecy” prevented him from saying more about the evidence that convinced him that Mata Hari was a spy who had to face a firing squad.

While U.S. intelligence agencies were not prepared to keep track of and stop German operatives who had slipped into this country, their counterparts in England did have the personnel and system to take on the German espionage machine. True, the British had more at stake in the war, but they also were much better prepared to fight Germany in espionage battles, with some of their best work done in the area of codes and ciphers.

Cable messages from Europe to the United States traveled through transatlantic cables that passed deep in the English Channel. The British saw the cables as an opportunity to gain access to secret diplomatic messages sent from Berlin to its ambassador in Washington, D.C. Knowing they couldn’t tap the cables the way they could tap phone lines, the British did the next best thing. The cable ship Telconia cut all five of the cables that carried communications through the channel. To make sure that the sabotage had a lasting effect, the Telconia rolled up a few of the cable ends on her drums and carried them to England. This act of sabotage was Great Britain’s first offensive act of the war.

As a result of the cut cables, Germany lost its most secure long-distance communications system. The Germans now had to rely on radio transmissions from their powerful wireless station at Nauen, a few miles from Berlin. Which was exactly what the British military knew they would have to do. And once the Germans began sending wireless messages, MI8, the British code breakers, began plucking them from the air. Of course, all German correspondence was sent in a complicated cipher system, so that was when the hard work began for the code breakers of MI8.

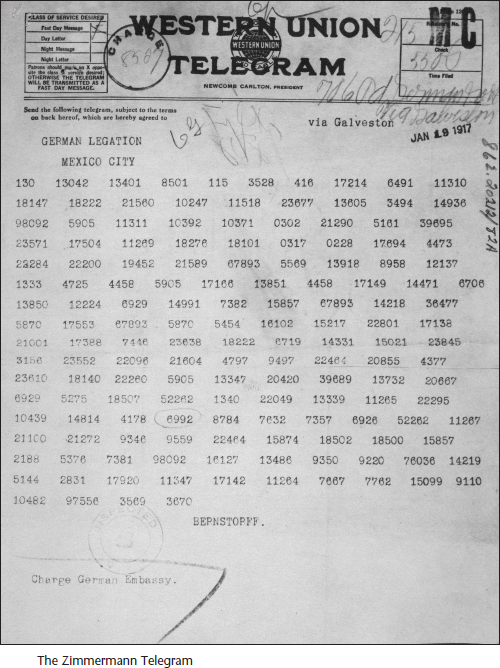

The intercepted messages were usually no more than rows of numbers in four- and five-digit groups, with an occasional three-number group included. For example, 67893 was the code word for Mexico. Such messages, sometimes as many as two hundred a day, were snagged day and night by the operators in Room 40, MI8’s cryptography center. To make the messages more difficult to decipher, the Germans frequently added another layer of security to their text by enciphering a message that was already written in code! In other words, the British code breakers needed to solve the cipher message before they could even take a crack at the coded message.

Given how this double disguising of a secret message could make decoding so much more difficult, it remains a mystery why the German telegram that finally convinced the American president to join the Allies on the battlefield in 1917 was simply a coded message.

While the task that faced the cryptanalysts in Room 40 was very intellectually demanding and physically taxing, the Germans committed some blunders in the way they sent their secret radio messages, giving the British help in their task. The first mistake of German intelligence was the error of arrogance, believing that the British were not up to the challenge of deciphering their messages. Another mistake they made was sending duplicates and even triplicates of some of their messages, with each one using a different cipher key. This ill-advised practice meant that the code breakers had a couple of different versions of the same message, giving them a much better chance of cracking the cipher. The men of Room 40 were, in the words of one historian, “reading Berlin’s messages more quickly and correctly than the German recipients.” This group of cryptography amateurs, who were generally recruited from college faculties, was able to achieve its success with “ingenuity, endless patience, and sparks of inspired guessing.”

On several occasions Room 40 received an unexpected but welcome gift when a German codebook was recovered after a sea battle and presented to the British code breakers. One such gift was a codebook from the German ship Magdeburg, a light cruiser that ran aground on an island off of Finland. When Russian ships quickly bore down on the cruiser, the captain of the stranded ship immediately did what all naval officers were taught to do: he ordered his signalman to bring him the ship’s codebook so he could throw the book, wrapped in lead covers, into the sea. But before the signalman could deliver the book to his captain, he was killed by Russian guns. When the Russians recovered his body, the sailor was still clutching the codebook in his arms.

The Russian admiralty decided that their British allies could make better use of the codebook than they could, so it was sent to London. The codebook was a bonanza for the British code breakers. Not only did it contain the columns of code “words”— groups of randomly selected numbers — on which the messages were based, but it also included a changeable key to the cipher systems used to obscure the coded messages.

The director of Room 40, Admiral Sir William Reginald Hall, was constantly on the lookout for any German codebook he could get his hands on. In December an iron-encased sea chest was delivered to his office. The chest had been hauled to the surface in the net of a British fishing trawler. It turned out that the chest was from a German destroyer that had been cornered and sunk by British warships. Among the personal papers and nautical charts in the chest, Hall discovered a codebook. It took the code breakers of Room 40 a few months to discover that the book contained the code system used by the German military to communicate with their naval attachés abroad.

After hours of hard work and their “inspired guessing,” the code breakers scored many triumphs. Their greatest success, however, came in 1917, when the war was at a critical point.

For nearly three years the war had taken its toll on the fighting nations. England maintained hope that, despite President Woodrow Wilson’s continued belief in his brand of neutrality, the Americans would reconsider, join the fight, and tip the balance of war in favor of the Allies.

On January 16, 1917, in a clear attempt to convince the Mexican government to help Germany in the war, Arthur Zimmermann, the German foreign secretary, sent a telegram to Count von Bernstorff, the German ambassador in Washington. The foreign secretary wanted to be certain that this message reached von Bernstorff, so he made arrangements for it to be carried aboard a U-boat to Sweden and from there to Washington through diplomatic channels.

As luck would have it, the departure of the sub was delayed. Impatient, Zimmermann turned to his second option: sending the message to his ambassador through the U.S. State Department. Although Wilson considered the United States to be neutral, he allowed messages to be sent to von Bernstorff via the State Department as a courtesy. The telegram sent, Zimmermann waited for a reply. What Zimmermann didn’t know was that the British were doing a thorough job of intercepting German wireless transmissions.

The first thing about the Zimmermann telegram that two Room 40 code breakers, Reverend William Montgomery and Nigel de Grey, noticed was its length, more than a thousand groups. Although the length itself was not suspicious, it was out of the ordinary. Then de Grey noticed the top group of numbers in the message, 13042, a variation of 13040, indicated a German diplomatic code. Since Room 40 had a copy of the 13040 codebook, they began using it to decipher the message.

As Montgomery and de Grey slowly made their way through the message, they noticed more and more oddities. For example, 97556 appeared near the end of the message; the 90000 family indicated important names that were not used very often in messages. We can imagine their shock when they realized that 97556 stood for Zimmermann. That single name fired the men with excitement as they began working on the message from the beginning.

In time, some of the coded “words” began to give up their secrets. They found most secret and For Your Excellency’s personal information. The men pushed on, discovering Mexico and Japan in the text. What could that mean? And what was Germany’s interest in Mexico? How did Japan figure into the plan? The men could not think of a reason for the connection among Germany, Japan, and Mexico. Quickly thumbing the pages of the codebook, the men worked on at a fever pitch.

They learned that there were two parts to the telegram. The first part — the longer of the two — carried bad news for all ships at sea, but especially American ones. Zimmermann was informing von Bernstorff that the German U-boat fleet would resume “unrestricted” submarine warfare on February 1. From that day onward, all ships, even those from neutral nations, would be fair game for deadly submarines patrolling the dark waters of the Atlantic.

Indeed, on February 3, the American steamship Housatonic was torpedoed without warning. This unprovoked attack on a passenger ship was another in a long line of similar acts of belligerence that had occurred in previous years. The most famous was the sinking of the steamship Lusitania in 1915, which killed all but two dozen of its 1,924 passengers, 114 of whom were Americans. The United States demanded that Germany disavow the attack on the Lusitania and make immediate restitution. Germany refused to do either. In March 1916 the French Sussex was sunk by a German submarine attack in the English Channel. The United States threatened to cut off diplomatic relations with Germany unless such attacks stopped.

If the first part of the telegram was ominous, the second section must have sent shivers of fear through Montgomery and de Grey. Although there were about thirty spots in the message that the men could not figure out, they had learned enough to know that it was time for them to notify their superior of their discovery.

Montgomery quickly fetched Admiral Hall. The head of Room 40, nicknamed “Blinker” for the uncontrollable twitching in his eyes, hurried into the room and stood in front of de Grey’s desk. Without saying a word, de Grey stood and handed the message to the small, ruddy-faced man. Hall’s eyes took in what Montgomery and de Grey had discovered. His eye twitches became more pronounced as he tried to assess the impact of what he was reading.

Hall well understood the gamble the Germans were taking. In two weeks they would unleash the full fury of their two hundred U-boats, in an effort to choke off the stream of American supplies that was keeping the Allied nations in the war. Surely, the U.S. would not permit their ships to be sunk by a belligerent nation. They would retaliate — unless their forces and attention were focused on a hot spot closer to home. Germany wanted Mexico to engage the Americans enough so they would be unable to send troops to help the Allies.

Zimmermann did not spell out what he hoped Mexico could do to assist the German war effort. The Germans weren’t looking for a long-term commitment, confident, as the telegram states, that the submarine warfare would compel “England to make peace within a few months.” With Mexico sharing an extensive border with the United States, perhaps Germany expected Mexico to stage attacks in their “lost territories in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.”

Arthur Zimmermann had no idea that “Blinker” Hall had read his secret message. But now that Hall had read it, what could he do with this information? On one hand, he believed that President Wilson, faced with the information in the telegram, would declare war on Germany. On the other hand, to share the telegram with Wilson would surely alert Berlin that the British had been reading their secret messages. As he walked back to his office, Hall considered ways that he could share the intelligence in the Zimmermann telegram and establish its authenticity without letting Berlin know that Room 40 had intercepted and read hundreds of their secret messages.

Hall decided that he needed to find a way to get a copy of the telegram that von Bernstorff would next have sent to Heinrich von Eckardt, the German ambassador in Mexico. He was convinced that there would be small but helpful differences between the original telegram sent by Zimmermann and the version that von Bernstorff would have sent to Mexico City. The message itself would be the same. Hall was sure that von Bernstorff would copy it carefully, but he was equally certain that it would contain telltale differences. For one thing, the dateline at the top of the telegram would be different, as well as the address and the signature. Yes, he needed to get his hands on a copy of that telegram, which would provide Wilson and Congress with proof of Germany’s intent with Mexico without compromising the activities of Room 40. Hall counted on Berlin to blame someone at the embassy or in the Mexico City telegraph office for letting the telegram fall into the hands of the Americans.

But how would Hall get that telegram? That would take some doing, he admitted. Then Hall remembered Mr. H., one of his trusted operatives. It was Mr. H. who had alerted MI8 to the suspicious activities of Sweden’s chargé d’affaires in Mexico City, Folke Cronholm. Sharp-eyed Mr. H. had noticed that Cronholm was making frequent visits to the telegraph office, far more visits than one would expect from a representative of the Swedish government, given the limited relationship between that government and Mexico.

Mr. H.’s report on Cronholm included a mention of the fact that von Eckardt had recommended Cronholm for an official decoration because, as the German ambassador wrote, Cronholm “arranges the conditions for the official telegraphic traffic for your Excellency.” Odd, Hall had thought on reading this, that Berlin would not simply give Cronholm some second-tier medal in a private ceremony. Why such public recognition for the Swedish diplomat?

Hall could think of only one reason for such an honor. And that reason stunned him. Was Cronholm helping to transmit coded German messages overseas? The answer came as soon as Room 40 deciphered some intercepted Swedish cable messages. As expected, each one began with a handful of Swedish code groups. However, the messages continued in German. Room 40 took to calling this ruse the Swedish Roundhouse. With this new information, British intelligence had begun monitoring Swedish cables. And it had all started with the keen observations of Mr. H. Now Hall wondered if Mr. H. could assist him again. He contacted his operative and made his request. Then he waited for Mr. H. to do his work.

Mr. H. quickly began talking to his contacts in the city. Soon he heard of a British printer in Mexico City who had been falsely arrested for printing counterfeit money. Mr. H. intervened with the British minister, who got the frightened printer released from custody and the charges against him dropped. The printer, overjoyed to be free, told Mr. H. that he would welcome the opportunity to repay the agent for his intervention. As a matter of fact, Mr. H. told him, there was a favor the printer could do for him.

The British agent had learned that the printer’s good friend — in fact, the first person he contacted for advice when the accusation leveled at him sent him into a panic — worked in the Mexican Telegraphic Office. Would he be able, Mr. H. wondered, to get a copy of the original telegram sent by von Bernstorff to von Eckardt? The printer was sure his friend could do that. He was as good as his word. Once Hall received the telegram from his agent, he was ready to approach President Wilson.

British government leaders didn’t present the Zimmermann telegram to Wilson for a few weeks. Hall reminded them that outrage was growing in America over Germany’s announcement late in the day of January 31 that the German navy would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. In fact, that policy provoked the U.S. government to cut diplomatic relations with Germany in February.

On February 24, when Hall sensed that the Zimmermann telegram would tip the balance in favor of the U.S. joining the Allied forces, the British home secretary presented the telegram to President Wilson. One week later, news of the Zimmermann telegram was splashed across the front page of American newspapers. On April 6, 1917, the Congress of the United States declared war on Germany and its allies.

Although the battlefield mayhem continued for another year, the added strength of U.S. troops proved to be too much for Germany. David Kahn, a leading authority of cryptography, wrote this about the Zimmermann telegram: “Never before or since has so much turned upon the solution of a secret message.”

By the time the war ended, the United States military recognized that it could no longer rely on other nations to provide it with crucial intelligence. Nor could it continue with the limited intelligence operations that it had established. Although World War II was more than twenty years in the future, the U.S. military was set on a course of developing a comprehensive intelligence network.

WHILE MATA HARI’S DRAMA played out in France, soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force were thrust into the thick of the horrible trench war in the same country. Braving mustard gas that burned their lungs and relentless machine-gun fire, the Allied forces held their ground. Nonetheless, things were looking grim for the Americans in the Meuse-Argonne campaign when they found themselves surrounded by the German army, making its last offensive push of the war.

When the Americans tried to send a message to headquarters pleading for help or discussing strategy, they suspected that the phone lines were tapped by the Germans. To verify their misgivings about the phone lines, they “let slip” a rumor that they were moving their supply depot. Part of this disinformation was the map coordinates that indicated where the supply depot would be. Within thirty minutes, the area that matched those coordinates came under heavy bombardment from German artillery. Even though the Americans encoded their messages, the German code breakers were able to easily crack the code and act on the intelligence that they discovered, making the American position even more dire.

The Germans seemed to have mastered many of the essentials of spy craft, and the Americans still did not have the counterintelligence apparatus to match them. Then, one night in early October, an army captain accidentally discovered a way to foil the German’s ability to break their codes. On that evening, Captain Lawrence was taking his customary walk among his men of the 36th Division of the 142nd Infantry Regiment when he overheard a conversation between two of them in a language he’d never heard before.

Curious, he asked the men what language they were speaking. One of them, Corporal Solomon Lewis, told Lawrence that they were speaking in Choctaw, their tribal language. Lawrence stared at the men, an idea growing in his mind. He asked if there were any other Choctaw speakers in the battalion. Lewis and his friend, Private Mitchell Bobb, figured there were eight others. In fact, two of them, Ben Caterby and Pete Maytubby, worked at headquarters.

With Lewis and Bobb at his side, Lawrence hurried to the communications tent. He called headquarters and told his commander to get Caterby and Maytubby, then stand by for a message. Lawrence’s idea was simple. He would dictate a message to Lewis and Bobb, who would translate it into Choctaw, then use a field phone to relay the message to Caterby and Maytubby, who would translate the message for their commander.

They quickly discovered, however, that there was one obstacle to overcome before the Choctaw could communicate essential military information: the language had no words for modern military terms, such as artillery, machine gun, or battalion. So Lewis, Bobb, and Lawrence put their heads together and came up with Choctaw words that could stand for such terms, including big gun for artillery, little gun shoot fast for machine gun, and ears of corn to indicate numbers of battalions. Filled with excitement, Lewis and Bobb made history that night in 1917 when they transmitted the first military message in the Choctaw language.

The plan was such a success that the commander ordered one Choctaw code talker be assigned to each field company headquarters. The first official use of the Choctaw code talkers gave the orders for two of the companies to withdraw from Chardeny on the night of October 26, 1917. The retreat was a success, and the use of messages transmitted in Choctaw grew. On October 27, the men used the code to plan an attack at Forest Ferme that came as a complete surprise to the Germans.

One can imagine the shock of the German code breakers when they started hearing the Choctaw messages. Remember, by so easily cracking a code system used previously by the Americans, the Germans had enjoyed complete access to intelligence sent by the American army. Suddenly, that changed. They were faced with a code that they couldn’t break because it was not based on a European language or the mathematical progressions that code breakers rely on. In fact, one captured German officer later said that their intelligence gatherers “were completely confused by the Indian language and gained no benefit whatsoever from their wiretaps.”

Within seventy-two hours of the initial Choctaw transmissions, the tide of battle turned. The American and Allied troops took the offensive, driving the Germans into full retreat. Because the war ended very shortly after Meuse-Argonne, the Choctaw code talkers didn’t get another opportunity to use their code in battle. But Choctaw and other Native Americans, mostly Navajos, served in a similar capacity in World War II.