Indica Books, in Southampton Row.

One of the most widely loved Beatles songs (in the general sense) is actually a Wings song that begins with the letter J, and that is Paul McCartney’s “Jet,” from the album Band on the Run. Most of that album was recorded in Lagos, Nigeria, but “Jet” was recorded entirely at EMI Studios in Abbey Road in London. It was the first British and American single to be released from the album, and it reached No. 7 or thereabouts in both countries.

What I didn’t know, I confess, was that the title may well have come from the name of a black Labrador puppy. Songs do not always have only one origin and/or one inspiration and the story varies, but Paul has recounted it this way: “We’ve got a Labrador puppy who is the runt, the runt of the litter. We bought her along a roadside in a little pet shop out in the country one day. She was a bit of a wild dog, wild girl who wouldn’t stay in. We have a big wall around our house in London, and she wouldn’t stay in. She always used to jump the wall. She would go out on the town in the evening. She must have made out with some big black Labrador or something; she came back one day pregnant.

“She proceeded to walk into the garage and have a large litter, seven little black puppies and Jet was one of those puppies. We gave them all names. We had some great names. There was one puppy called Golden Molasses.” That’s a good song title if ever I heard one.

Then there was also one puppy apparently called Brown Meggs, named after a Capitol Records executive. I know that’s a really obscure bit of information, but I remember Brown Meggs very well. He was a key senior executive at the Capitol Tower in Hollywood whom I liked very much for his obvious intelligence and for his unusual attitude. Most Americans we met seemed full of boundless enthusiasm, which was impressive—but Brown had a much more sardonic and sceptical approach to the record business, and to life in general, which was unusual, and I suppose came as something of a relief at that point. He was funny as well—and also clearly a man of taste since he was the executive who agreed to release “I Want to Hold Your Hand” as a single in the United States. I can certainly see why Paul would name a puppy after him. Anyway, that’s all we know about Jet, the little black dog whom I never met. But I do love “Jet,” the song named in his honour.

J is also, of course, the first letter of the first name of the greatest spy who ever lived, at least in our literary imaginations, James Bond. Mr. Bond had quite a bit to do with the British music scene in the ’60s in a couple of different respects. First of all, the classic and instantly memorable and evocative theme music was played by a brilliant session guitar player called Vic Flick. Vic also played the lead guitar on “A World Without Love.” So, thank you, Vic, a master guitar player for a master spy and for a pair of young and ambitious singers.

Of course, the other connection between James Bond and the Beatles is that Paul McCartney wrote one of the classic James Bond songs, “Live and Let Die.” A very exciting movie and a terrific song to match. It may be the most famous Bond song, or perhaps second to Shirley Bassey’s dramatic “Goldfinger,” but certainly those two would be my favourites among the Bond songs. “Live and Let Die” is also usually one of the highlights of Paul’s live show. Those of you who have seen him live know that the song is always accompanied by giant pyrotechnic blasts and explosions and fire all over the stage and is guaranteed to get the audience on its feet.

Now, since the theme of this chapter is the letter J, it would be both unfair and unwise to talk about Paul McCartney for too long because John (the J Beatle) would undoubtedly get jealous. We all know that he was capable of doing so, and indeed he wrote an entire J song on that very subject, “Jealous Guy.”

“Jealous Guy” is a remarkably intense and honest song which John began writing in India and kept around for a while, changing the lyrics and adjusting the melody before finally releasing it on the Imagine album. The lyrics were originally inspired by a lecture given by the Maharishi.

John cut an excellent track of the song in London in mid-1971 with Nicky Hopkins on piano, Klaus Voormann on bass, and Jim Keltner on drums (one of John’s favourite rhythm sections) but adding on this occasion Joey Molland and Tom Evans from Badfinger (who were around Apple a lot at the time) on acoustic guitars.

Lyrically, John acknowledges his jealousy and even his possessiveness—though the way I read the song it could apply not only to John-Yoko jealousy (of the usual marital kind) but also perhaps a little to John-Paul jealousy (of the two-brilliant-songwriters kind). Maybe it began life this latter way in 1968 and morphed into a Yoko-related song over the next couple of years.

Now, before George Harrison turns into a jealous guy, let’s turn to one of his tracks, a great J song called “Just for Today,” from his Cloud Nine album. This album was co-produced by George and Jeff Lynne and was both a critical and commercial success. “Just for Today” is a mournful song, asking not to feel sad and lonely just for today. Starting with solo piano, it is a beautiful and plaintive record. To me it actually has a little of the flavour and wistfulness of “Imagine” to it—even though John’s lyrical wishes are more universal in nature and George’s more personal.

George, as everyone knows, was one of the most creative and significant guitarists in the history of rock and roll, but another fantastic guitarist (and an even more spectacular one) whose path crossed that of the Beatles was another J person, Jimi Hendrix.

My story about Jimi starts with Brian Epstein, who at one point in his career leased a theatre in London called the Saville Theatre. He had decided that it would be both productive and fun to have somewhere to put on shows himself. Brian promoted a series of concerts at the Saville Theatre which have become legendary in retrospect; so many great acts played there. Among these shows was one which included a set by the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Jimi himself had played in some of the clubs around London, at the Scotch of St. James and the Bag O’Nails, sitting in with other London musicians, and I’d seen him at one of those, and we had all heard about him. Everyone was talking about him and what an extraordinary guitar player he was. But then he went away for a while, working with his manager Chas Chandler, who was the bass player in the Animals, to assemble this new band, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, with Mitch Mitchell on drums and Noel Redding on bass. And their first London gig was going to be at the Saville Theatre on June 4, 1967.

Every traditional British theatre has a royal box that is reserved for the Queen, should she decide to attend whatever event is taking place there. Inexplicably, and no doubt she regrets it to this day, Her Majesty did not choose to attend the Jimi Hendrix premiere at the Saville Theatre in London, which meant that the royal box was available for Brian Epstein’s use. And Brian, of course, invited the Beatles, and the Beatles kindly invited me. So I got to go to this show, sitting in the royal box with George Harrison and Paul McCartney, and watch this extraordinary concert. And no question, the act that we were all waiting for was the Jimi Hendrix Experience, who more than lived up to our sense of anticipation and totally blew our minds.

First of all, Jimi had just heard the Beatles’ new album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which had come out only three days earlier. And apparently he had learned the title song just by listening to it on the radio; he taught it that afternoon to the other members of the band and they played it onstage that night—and brilliantly well. As I recall, they opened the show with it, which completely surprised and astonished Paul and George. And then of course Jimi went on to do his whole show, playing the guitar with his teeth and behind his head, and setting fire to it, quite apart from playing brilliant, virtuosic, and highly original music. We were all totally overcome; to be fair we also had smoked a little hash, I have to admit, in the royal loo attached to the royal box—not the Queen’s private stash, sadly, but some we’d brought with us. So we were a little stoned, but my God, seeing and hearing all that for the first time was an experience I shall never forget, and I was very privileged to have been there.

I met Jimi Hendrix properly only once—a conversation rather than just a post-show congratulation. I was at a party somewhere near Marble Arch in London and was quite nervous when I found myself sitting across from Jimi. Somehow, though, we ended up talking about science fiction, of which he turned out to be a knowledgeable devotee. We discussed our shared admiration for Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy and explored the philosophy and historical theories of Hari Seldon—who would have thought that we would bond briefly over psychohistory and mathematical sociology? But sadly I never saw him again.

When we weren’t having our minds blown by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Paul McCartney and I were both interested in avant-garde literature and plays and music and the experimental arts in general. A lot of it we were turned on to by our mutual friend Barry Miles. One of the writers we learned about from the profoundly knowledgeable Miles was the French playwright Alfred Jarry, whose most famous work was Ubu Roi, or Ubu the King. I have never seen the play onstage (it is not performed that often), but Paul and I both read it—and it is not easy to describe. Nonsensical, grotesque, and vulgar, it opened and closed in Paris on December 10, 1896, having received a literally riotous reception. In some respects, the story parodies Macbeth and some parts of Hamlet and King Lear, but the dialogue is obscene and childish.

In the course of his writing, Jarry also invented an entire “science,” which he called ’Pataphysics (the apostrophe is intentional) and all things pataphysical. Equally hard to explain (because it resolutely makes no sense), it has been said that the science of pataphysics is to metaphysics as metaphysics is to physics. Does that help? It has also been described as the “science of imaginary solutions.” Apparently one visitor to the Society of ’Pataphysics (which still exists), on pressing for a clear definition, was handed a list of a hundred different definitions. He was told to choose whichever one he liked. He was also told that most of the definitions were completely wrong but that it would not be pataphysical to try to say which were which. I confess I find all this entrancing—and it would appear that Paul found the world of pataphysics inspiring as well. The word pataphysical may, in fact, ring a bell with you, because Alfred Jarry—with a J—influenced Paul’s lyrics to the very surreal song “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Quizzical Joan, after all (and another J), studied pataphysical science in the home.

In addition to turning Paul and me on to avant-garde writers like Alfred Jarry, Barry Miles was part of a larger countercultural scene in London. The whole hippie age was beginning, when everyone seemed to be wearing beads and flowers and smoking too much dope and having a good time, and we all wanted to be part of this, too. We also related the hippie age to the beat movement that had preceded it, because we had all read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road; I had even recited Allen Ginsberg’s Howl in the school poetry reading competition at Westminster, which caused a bit of consternation. It is to the school’s credit that they let me do it uncensored—and in a really bad fake American accent.

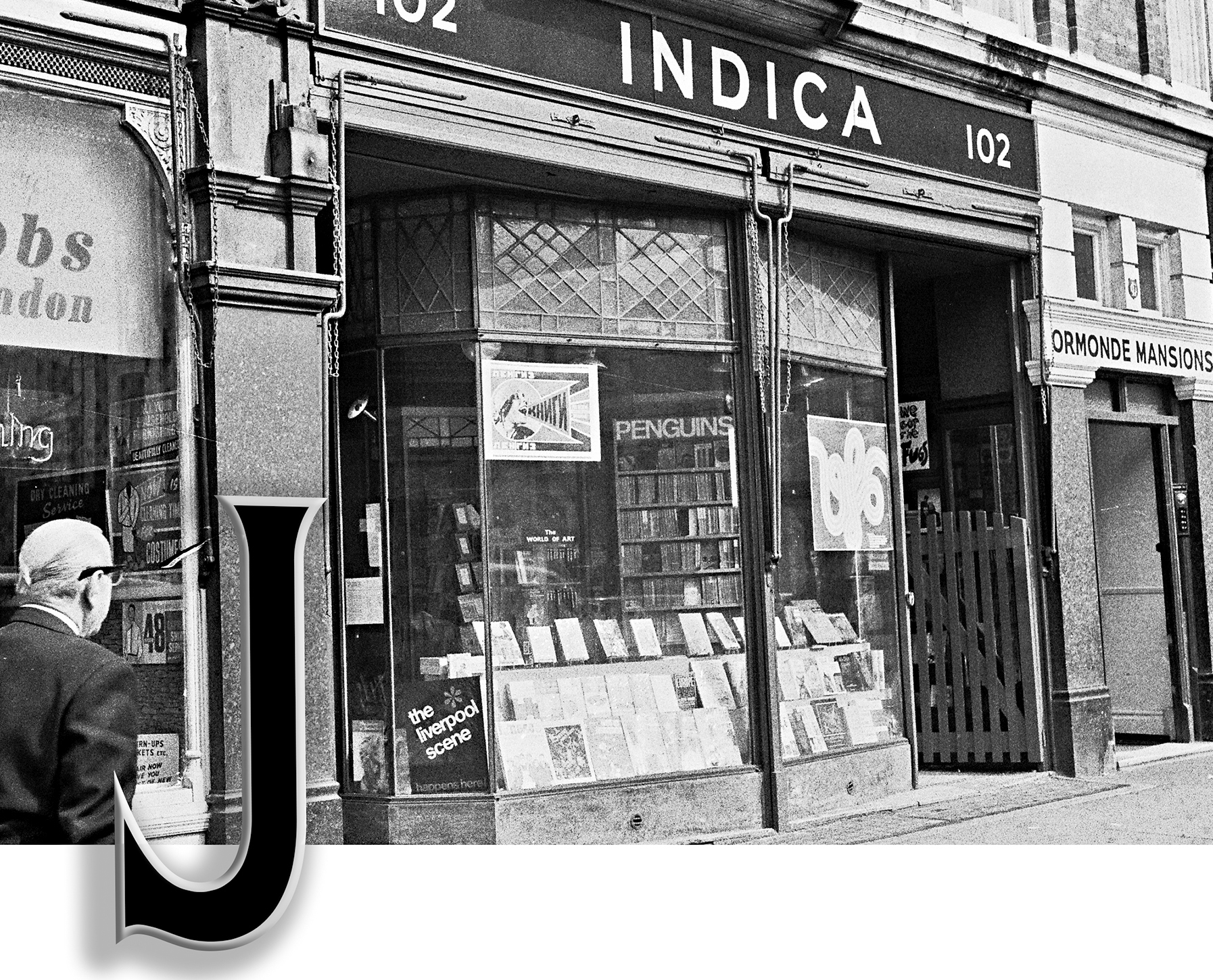

In 1966 Miles and I decided to team up with another friend, John Dunbar, and start a bookshop and an art gallery to try to create a focal point for this new and exciting counterculture. We loosely based it on places like the City Lights bookshop in San Francisco, which we admired very much. In addition to being exceptionally well read, Barry Miles had been a bookseller and knew all about the book business. As I recall, I first met John Dunbar because he was the brother of Gordon Waller’s beautiful girlfriend Jenny Dunbar—strange how it all ties together. John had studied art at Cambridge University and knew a lot about the art scene—and the three of us decided to open both a bookshop and an art gallery. We named the enterprise Indica. We chose that name based on the plant Cannabis indica. You may be aware of this plant—it’s been in the news a lot lately.

Inside the Indica bookshop, with Barry Miles and Jane. And at right, Paul’s hand-drawn map showing how to get to Indica Gallery.

The bookshop itself was at 102 Southampton Row. Miles managed the shop, but whenever I wasn’t out on the road, I would go in and help, as did my sister Jane from time to time. And her boyfriend Paul was very helpful as well; I remember the day he helped us install the shelves immediately behind the counter. He was a useful chap to have around, you know—providing hit songs and shelf installations with equal facility. Then when the time came to start the art gallery at a separate location, Paul drew the map that showed customers where it was.

John Dunbar was always on the lookout for cool new artists, and we had several significant and successful exhibitions. In particular John had heard a lot about an innovative Japanese-American artist by the name of Yoko Ono, and we all thought she sounded just right for Indica. So John got in touch with Yoko, and she agreed to do a show for us. We were very excited; she sounded really cool. Dates were chosen and plans were made. We took an ad out in the local underground paper International Times—which was actually published from the basement of Indica Books.

The advertisement in the International Times for Yoko Ono’s exhibition at Indica Gallery.

We arranged for a normal press opening, but we also invited our friends and family to come and have a look the day before. By this time, of course, the Beatles were included among our friends, so we invited all of them, and John Lennon came.

Here’s his account of what happened:

Yoko was having an art show in London at a gallery called Indica Gallery and I heard this was going to be happening, so I went down the night before the opening. Also the first thing that was in the gallery as you went in, there was a white stepladder, and a painting on the ceiling, and a spyglass hanging down. I walked up this ladder and I picked up the spyglass, and I see teeny little writing that just said yes. If it’d said no, or, something nasty, like rip-off or whatever, I would have left the gallery, but because it was positive, it said yes, I thought, okay, it’s the first show I’ve been to that said something, you know, warm to me. So then I decided to see the rest of the show, and that’s when we met.

Well, of course, being partly responsible for John meeting Yoko for the first time could be seen by some as making me partly responsible for the breakup of the Beatles, but I entirely reject that responsibility and that whole perspective. I think Yoko’s extremely cool—she was then, and she is now.

Picking up our alphabetical journey, another J who played an important role in the Beatles’ career was Dick James. Dick started out as a singer; he recorded the theme for the 1950s British television show The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring Richard Greene (which also aired in America)—“Robin Hood, Robin Hood, riding through the glen,” and so on. In yet another odd coincidence, I made several appearances in the Robin Hood series myself in my days as a child actor. Several times I appeared as Prince Arthur (protected by Robin from the threats of King John and the Sheriff), and once with my sister Jane as a pair of “peasant children” whose father had been wrongfully imprisoned by those same villains. Dick later became a music publisher and through his close friendship with Brian Epstein ended up being afforded the extraordinary privilege of publishing the Beatles’ songs.

It was no small thing to co-own the Beatles’ publishing—in conjunction with the Beatles themselves, but Dick controlled it. And that was the beginning of quite a long story about where their publishing has ended up, who bought it, who sold it, and so on. There are various characters involved in this lengthy drama, Dick James being one of the first, Michael Jackson being another, Sony Music being another, and so on. Everyone made a fortune out of it, and many continue to do so. The Beatles have always received their songwriting royalties, but certainly their business lives would have been a lot simpler and more profitable had they owned and controlled their own publishing from the beginning. That said, Brian Epstein certainly did nothing wrong—he correctly saw Dick James as someone with connections who could be (and was) a valuable ally in getting the Beatles’ career off the ground and who was a fellow believer in their music and their talent.

As you may know, Michael Jackson ended up buying John and Paul’s publishing, following advice he got from Paul McCartney himself, who told Michael how well he had done owning copyrights. Paul owns the copyrights to many compositions by one of my great heroes, Buddy Holly (along with other major catalogues), and that has worked out extremely well for him.

But when Paul gave Michael Jackson this very sage advice, we can be confident that he was not expecting Michael to turn around and buy the publishing rights to Paul’s own songs! And then at one point Michael is said to have declined to sell it back to Paul. All rather complicated and tense. I would imagine their relationship suffered a bit in consequence. But in the meantime, when the relationship was good, they recorded a couple of really successful songs together. And since Michael Jackson is a J, let’s look at those tracks.

The first big hit for the duo was “The Girl Is Mine,” which was written by Michael and was included on his incomparable Thriller album. Paul and Michael recorded the track in Los Angeles (with the legendary Quincy Jones producing), and several members of the band Toto played on the track. They were all seasoned studio musicians and are each famous in his own right. Jeff Porcaro was one the greatest drummers with whom it was ever my pleasure to work—he played on several Cher tracks I produced. The keyboard player David Paich is an all-around musical genius, and guitarist Steve Lukather combines amazing technical skill with the ability to totally rock out. You might have seen him doing so on the road of late with Ringo’s All-Starr Band.

Paul and Michael’s second hit together was “Say Say Say,” which Paul included on his Pipes of Peace album. Paul wrote the song specifically to be performed by himself and Michael Jackson, and they recorded it at AIR Studios (with George Martin producing) while Jackson was staying at Paul and Linda’s house in London. Some further overdubbing work was done in Los Angeles, and when it was released, the brilliantly catchy McCartney hook did its job and the record was No. 1 on the Billboard chart for six weeks. It is almost an R&B kind of groove and in a minor key—and reminds me a bit of the classic “Harlem Shuffle” in that regard.

Another J that you may not immediately associate with the Beatles is jazz. There have been a few great jazz versions of Beatles tunes, and I’d like to single out three of them. The first is by a brilliant jazz legend called Ramsey Lewis. He’s an extremely soulful and funky pianist. In fact, he had a big hit record himself many years ago with an instrumental version of the pop tune “The ‘In’ Crowd,” if you remember that, and even though he is a jazz player, I think even a dyed-in-the-wool pop fan can love the groove that he creates and the feel he gets as he does his jazz version of “A Hard Day’s Night.”

A second remarkable jazz cover of a Beatles song worth checking out is the brilliant version of “Yesterday” by a pianist and singer by the name of Shirley Horn. If you don’t know her work, she’s really good and well worth listening to. She makes this song almost unbearably sad. This was recorded on her very last album, and she was battling breast cancer at the time and had lost her foot to diabetes. But even in this depressing context, Shirley Horn’s artistry gives us a deeply moving version of one of the most beautiful songs ever written.

The third jazz version of a classic Beatles song that I’d like to point out is much more cheerful. In the big band era, there were two killer orchestras, Count Basie’s and Duke Ellington’s. They had entirely distinctive sounds (one can tell within a few bars which band one is listening to), and they always had remarkable arrangements. Each band also had its own remarkable and distinctive soloists. To a jazz fan, if you hear Lester Young you know it is Basie and if you hear Johnny Hodges you know it is Ellington.

The Count Basie Orchestra recorded an arrangement of “All My Loving” that’s truly excellent. It’s bouncy. It’s happy. It’ll cheer you up after that sad version of “Yesterday.” Count Basie himself plays the piano and leads the band.

You may have noticed that in this entire chapter, I have not mentioned a single J song performed by the Beatles themselves. That’s because there is only one such song, and I saved it for the end. The letter J may have only one Beatles song, but it is one of the most gorgeous, moving, and intense songs that was ever written by anybody, let alone by Lennon & McCartney. It is John Lennon’s classic masterpiece “Julia.”

The lyrics to this song are very beautiful, and they also provide an example of the breadth of John Lennon’s reading and curiosity. The ’60s saw a resurgence of interest in a Lebanese-American poet called Kahlil Gibran, who was born in 1883 and first became popular in the 1920s. By the mid-’60s his book The Prophet was widely quoted at weddings and so on—and clearly John had read his work as well. The line “Half of what I say is meaningless, / But I say it just to reach you” is only a slight alteration from Gibran’s Sand and Foam, in which the original verse reads, “Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you.” John also adapted the lines “When I cannot sing my heart, / I can only speak my mind” from Gibran’s “When life does not find a singer to sing her heart she produces a philosopher to speak her mind.” I see this kind of “borrowing,” which happens all the time in all the arts, as a high compliment and a joy—and I also think the words and sentiments in question are even more effective when adjusted and set to music than they were on the page. And it is interesting to be able to see what, beyond John’s love for his mother, Julia, inspired this remarkable song.

John always felt that he had lost his mother twice; once when he was sent to live with his aunt (a complicated story) and again when Julia died young in a shocking traffic accident. John’s evocation of his late mother is haunting and yearning and vulnerable all at once. It turns out that no one can sing a song of love, or write one, more touchingly than the acerbic and sometimes even angry genius that was John Lennon.