Badfinger (from left to right): Pete Ham, Tom Evans, Joey Molland, and Mike Gibbins.

Having taken our journey through the letter A, we naturally move on to B.

To start us off, I have picked one of my favourite Beatles recordings that begins with B, “Baby It’s You,” partly because it was written by Burt Bacharach—a lot of B’s there. It was originally recorded by the brilliant girl group the Shirelles, and the Beatles did a great cover version. As with so many other songs they recorded or performed, I suspect that by creating such a convincing version of the song they brought it to the attention of many people on both sides of the Atlantic who had not even heard the original. This is a common phenomenon. There are still people who think, for example, that “Twist and Shout” is an original Beatles song.

Gordon and I had the pleasure of sharing the bill with the Shirelles back in the ’60s—and they were terrific every night. Three remarkable singers, sometimes switching who was singing lead and who was singing harmonies and responses—but remaining perfectly balanced and unequivocally soulful throughout. They had many excellent hits, including the first No. 1 record ever by an African American girl group, “Will You Love Me Tomorrow”—before the Supremes or anybody else. They were inducted, deservedly, into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996. I went to that ceremony and got to say hello to them again after a gap of several decades. My favourite Shirelle was Doris Coley because I got to know her well during the tour, and it was exciting to see her again. We used to sit next to each other on the bus and talk, and it was Doris who had to explain to an overconfident and self-righteous white English boy that the two of us should not necessarily sit together when we stopped to eat at diners in certain parts of the South, even in the ’60s.

That tour with the Shirelles was the Dick Clark’s Caravan of Stars, and it lasted for a couple of months in 1965. One of the fun things about this tour was that there was such a variety of acts on the bill. In this case, there were the Shirelles, the Drifters, Brian Hyland (if you remember “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polkadot Bikini”), and Tom Jones—and, of course, Peter & Gordon. We were all on a regular Greyhound bus, sleeping in hotels only every other night but having the time of our lives despite the considerable discomfort. It was really fun.

The Beatles were big Shirelles fans, of course, and “Baby It’s You” is not the only Shirelles song they recorded—or even the only B song from the Shirelles. There is also “Boys,” one of Ringo’s great vocal performances, and he still does it from time to time when he is out with his All-Starr Band, and it’s always a pleasure. Maybe it makes more traditional sense sung by a woman, but Ringo sings with such declaratory ebullience and joyful confidence that it totally works. I saw him perform it recently at Joe Walsh’s birthday party, and the way he plays and sings simultaneously with such an intense groove and his uniquely splashy hi-hat style has never rocked more than it does now!

On to another B song, a couple of B’s right there, “Baby’s in Black.” Three B’s to be exact—a veritable swarm of B’s. Listening to this song, one can tell that among the Beatles’ greatest influences were the great Everly Brothers (who were also a major influence over my early career). The Beatles were huge fans.

All of us listened to the Everlys and tried to emulate their beautiful singing, the kind of close-harmony major thirds that they executed so perfectly. And one of the classic records which was a huge hit in the UK and which we all learned to play and sing (and I guarantee you, even though I don’t think there are any recordings of it, that John and Paul must have sung this song as well) was “Bye Bye Love.” George Harrison loved this song so much that he did kind of a rewrite. It is notable that the version George Harrison recorded of “Bye Bye Love” has him credited as an additional writer, and indeed it is a pretty radical rethink of the song and a very cool one. He totally changes what used to be the very simple rhythm and structure of the song, introducing all kinds of syncopation and rhythmic movement along with a lot of contrapuntal instrumental parts. George’s own twelve-string acoustic rhythm part holds it together, but the fretless bass and the slide electric guitar noodle around all over the place in an interesting way—and the song itself is no longer a straightforward duet but less predictable all round. It is always worthwhile approaching a good song in an entirely new way, and I would rate this as a largely successful experiment.

Most of us Everly fans took a more conventional approach in creating our versions of their songs. Certainly, we duos tried to match the brilliance of their arrangements as closely as we could. But the originals were always the best.

Now, when I say that none of us were as good as the Everly Brothers, a duo that certainly came very close was John Lennon and Paul McCartney. A fine example of John and Paul singing together in the Everly style is “Baby’s in Black,” which is sung with rock and roll strength. It’s got a bit of John’s intensity in there that really makes it rock. Though of course the Everlys could rock like crazy as well when they had a mind to. Check out “The Price of Love,” for example.

Staying with early influences in the letter B, let’s move on to a song that was a great favourite of John Lennon’s. Everyone—the Beatles, Peter & Gordon, and all the British Invasion bands—were major Gene Vincent fans. Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps were a bigger deal in the UK than they were in America. And one thing we all had in common was great affection for their first and biggest hit, of which John Lennon did a great cover for his Rock ’n’ Roll album, a definite B song called “Be-Bop-a-Lula.”

I think my favourite version of that song is Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps doing it in the great movie The Girl Can’t Help It. If you get a chance, jump on YouTube and watch it. Everyone is in that movie. Fats Domino is in it, Gene Vincent is in it, Little Richard is in it—and Jayne Mansfield is in it, which is a whole other thing, of course! It is well worth watching. One of the great rock and roll movies, and the Beatles were big fans of it, too. In fact, in 1968 the Beatles interrupted the recording session for “Birthday” when they realized that they were about to miss the premiere of The Girl Can’t Help It on British television. They all walked to Paul’s house in Cavendish Avenue to watch it.

Now on to a couple of very important B composers, Chuck Berry and Ludwig van Beethoven—two more B’s who are certainly on the A list—and in one of his most famous songs (one that the Beatles covered brilliantly), Chuck is urging Ludwig to roll over! Every guitar player learned from Chuck Berry, who virtually invented a simple and highly effective style of rock and roll guitar playing all his own, incorporating a straightforward rhythm under the singing with wildly imaginative solos. These included some signature licks which occurred often in his work, but we never tired of them. Indeed, we tried to play every one. George Harrison was no exception, and you can hear a lot of Chuck Berry’s influence in much of his work.

The Beatles didn’t just listen to Chuck Berry’s records, of course; they also covered some of his songs. In the Beatles’ cover of “Roll Over Beethoven” (a bit slower than Chuck’s original), George begins with a straight Chuck lick, virtually unaltered, but from then on they make a number of interesting arrangement changes—adding handclaps on every quarter note, which propels the track along very effectively—and then they change the pattern for the “feel like it” verse, giving that section an almost bridge-like quality. Thus are some imaginative production ideas applied to a classic song in a way at which the Beatles excelled. But one thing Chuck still has over them is the excellent piano work of Johnnie Johnson, Chuck’s brilliant accompanist—and there is a whole story there for anyone interested. Many musicologists believe that Johnnie deserved co-writing credit on many of Chuck’s songs—yet when Keith Richards searched for Johnnie in order to ask him to play in the band for the Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll Chuck Berry documentary in the 1980s (for which Keith was the bandleader), he found him driving a bus for a living.

One final note on “Roll Over Beethoven” (and its witty lyrical concept) which I cannot resist is that even if Beethoven had got the message from Chuck about the invention of rock and roll, he could not have actually told Tchaikovsky the news—at least not on this earth. Beethoven died in 1827 and Tchaikovsky was born in 1840—I suppose Ludwig could have left a note!

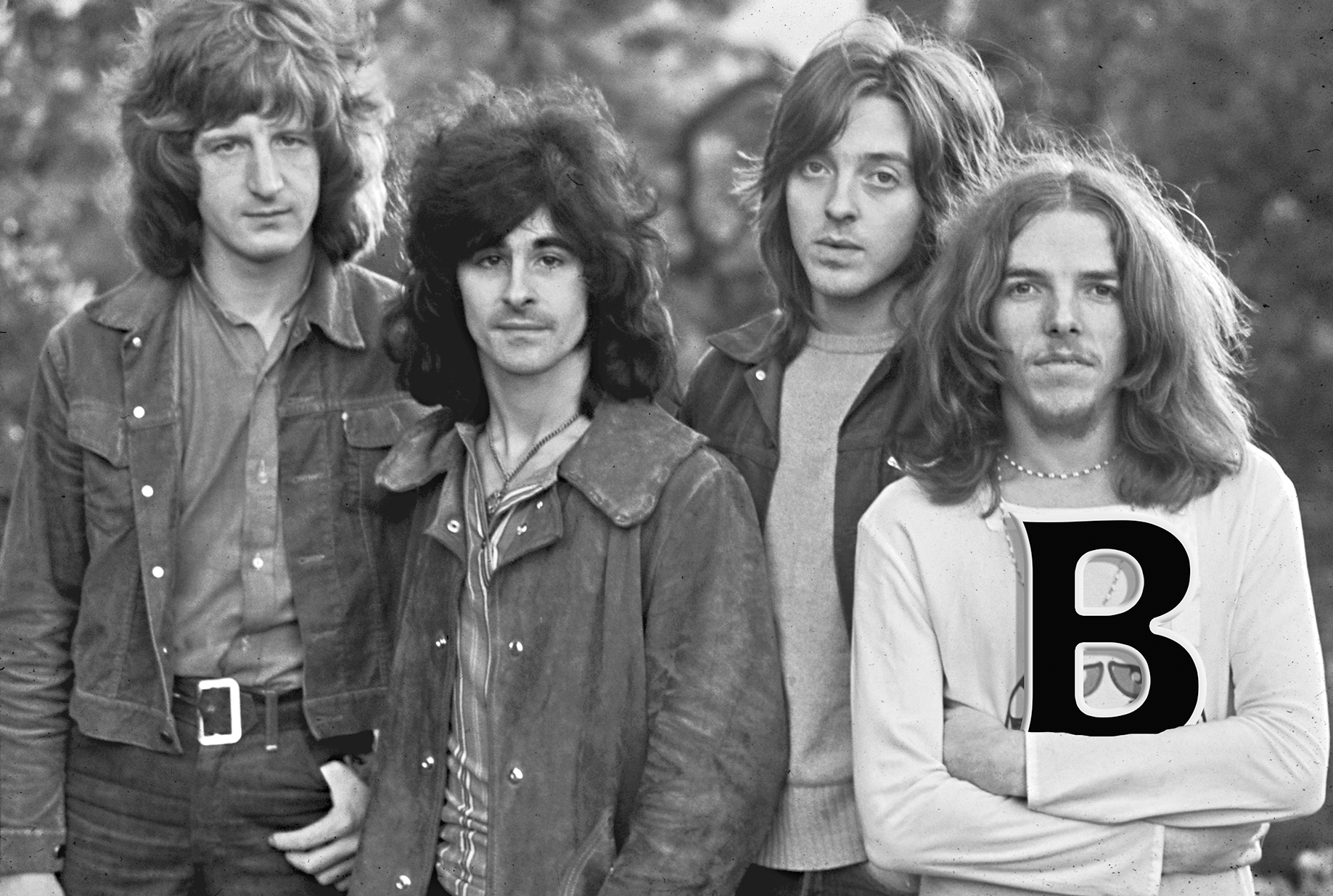

The Beatles didn’t just learn from other musicians, of course; they also reciprocated in so many ways. They were by far the most influential band of all time, and they went to great lengths to help other musicians—indeed, that was the original concept behind Apple Records. When I was head of A&R for Apple (which was an extremely fun job, I assure you), we signed quite a number of bands including one called the Iveys. The Iveys were brought into Apple by Mal Evans, the Beatles’ old friend, confidant, and roadie. It is worth remembering that when the Beatles began, Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans were the whole team, and Mal was a solid and reliable presence in whom everyone had great confidence. I liked him very much, and we were all delighted when he brought a tape of this excellent band he had found into one of my weekly A&R meetings. We signed them. We made an album. It had one small hit in the UK, “Maybe Tomorrow,” but it didn’t do much in America. And then we had an idea. First, we changed the Iveys’ name to Badfinger; I think the name change suggestion originated with Capitol Records in the U.S., who were not happy with “The Iveys” as a name. Neil recalled that the original working title for “With a Little Help from My Friends” was “The Badfinger Boogie,” and he suggested Badfinger as a new name for the Iveys. Then Paul gave them a song which he had written for the purpose, and it was a huge hit—“Come and Get It,” with its catchy opening line, “If you want it, here it is, come and get it.”

Paul recorded a demo of the song and then produced it with the band and apparently pretty much insisted that the produced version be exactly the same as his demo. I’ve heard both, and they are extremely similar, it must be said. Paul produced another cool song for Badfinger called “Carry on Till Tomorrow” which has a really excellent and imaginative string arrangement from George Martin.

Both “Come and Get It” and “Carry on Till Tomorrow” were part of the soundtrack for a movie called The Magic Christian, the stars of which were Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr. So let us move on to Ringo for a minute and explore a couple of his B songs. Ringo is more than just a brilliant, amazing, inventive drummer; he is also a reliably good and enthusiastic singer. And he is at his jolliest and most enthusiastic on his solo record “Back Off Boogaloo,” a song that he wrote himself. Ringo was inspired, apparently, by Marc Bolan of the band T-Rex, who encouraged him to write those lyrics and begin the song. George Harrison helped him finish the song and then produced the record for him. And the two of them came up with a really catchy song which was a major hit.

Another irresistible Ringo record is a quadruple B, “Bye Bye Blackbird,” an old and classic tune that Ringo included on his Sentimental Journey album. It also features the banjo, another B and an instrument I love.

Since we are talking about songs that start with the letter B and I just mentioned blackbirds, we cannot of course fail to give every possible consideration to one of Paul’s finest songs, “Blackbird.” I remember hearing it shortly after it was written. I seem to recall that Paul had already moved out of my family’s home by that time, and I was visiting him in his house at Cavendish Avenue. The song impressed me then, and it impresses the hell out of me now, I must say. It is a remarkable composition and a beautiful piece of guitar playing.

What I didn’t know at the time was that “Blackbird” was influenced heavily, and Paul has explained this, by the Bourrée in E Minor by another very fine composer beginning with B, Johann Sebastian Bach. (A bourrée is a lively French dance.) To the casual listener, the two pieces do not appear to have that much in common—when great composers are influenced by each other’s work, the connection is not always obvious—but when Paul explains how he had worked up a simplified and somewhat rearranged version of the Bourrée to play on guitar (and which became something of a party piece), it all starts to make sense. I imagine that Paul had heard a version by Segovia or someone like that (there were many Segovia albums lying around in our house, and I was already a fan) and that he had then skipped the bits he could not quite figure out and created an edited version which led him eventually to the creation of “Blackbird.” So the story ended very well indeed!

George had a lot of cool B songs, too, but I think my favourite is probably “Beware of Darkness” from the All Things Must Pass album. Brilliant song, brilliant record. A remarkable composition which includes some very surprising and emotionally spooky chord changes. No sooner has the introduction got us sitting comfortably in the key of B than it takes a disconcerting chromatic slide down to G major followed by an even more unexpected half step up to G-sharp minor and C-sharp minor. Not necessarily comfortable but certainly beautiful in its own way, as if the spiritual darkness and temptation we are being advised to avoid (I take this song to have a kind of “Get thee behind me, Satan” theme) were following just behind through these jagged changes. And cool lyrics as well. I especially like “Beware of soft shoe shufflers, dancing down the sidewalks”—certainly plenty of those in the music business!

Another very cool storytelling song that starts with B comes from John: “The Ballad of John and Yoko.” A Beatles record officially, but as far as I know it’s just John and Paul on the record, with Paul doing those great harmony parts. It’s also the ballad of Mr. B in the sense that Peter Brown is referred to in the lyrics. Peter Brown was the Beatles’ right-hand man and organized everything in their lives, including evidently the John and Yoko wedding and various travel details while also fending off the press and so on. Peter is a good friend of mine and now lives in New York. I see him from time to time when I am there, and dinner is always a pleasure, and that song made him famous.

Another lyric I found interesting is “you can get married in Gibraltar near Spain,” and looking at it again, I wondered whether it had been an issue at the time. The status of the tiny peninsula of Gibraltar has long been a big issue between Britain and Spain. Gibraltar is, currently and in fact, part of Britain. It’s just about all that’s left, I think, of the British Empire at this stage! But Spain (with, it must be said, a certain geographically irrefutable logic) thinks it should be part of Spain. So “Gibraltar near Spain” is, politically, hugely incorrect from a Spanish perspective. I looked it up and the Spanish did actually lodge an official protest at the time against Gibraltar being described in the song as “near Spain” when they regard it as part of Spain!

But in fact it is still British. God Save the Queen! Let’s move on.

Our final song, our final Beatles B song for this chapter, one of my very favourites influenced by both Chuck Berry and the Beach Boys, a couple of B’s right there, is “Back in the U.S.S.R.” It’s kind of a tribute to Chuck Berry’s “Back in the U.S.A.” and probably is even better known now than the original song. (I say that even though Chuck’s original was a great favourite of mine to the point where I enjoyed a giant hit when I produced a new version of it with Linda Ronstadt in 1978.) The Beach Boys–style harmonies on “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” of course, are unmistakable.

Yet again we see the Beatles (and Paul as a composer) break totally new ground with this song. Combining the influences of two very different and equally legendary schools of American rock, they use that blend as the basis for a witty, international, and surprising twist on the traditional home-sweet-home song format—and thus provide a fitting ending for this chapter and for our exploration of the very important letter B, which, as we can never forget, is for Beatles.