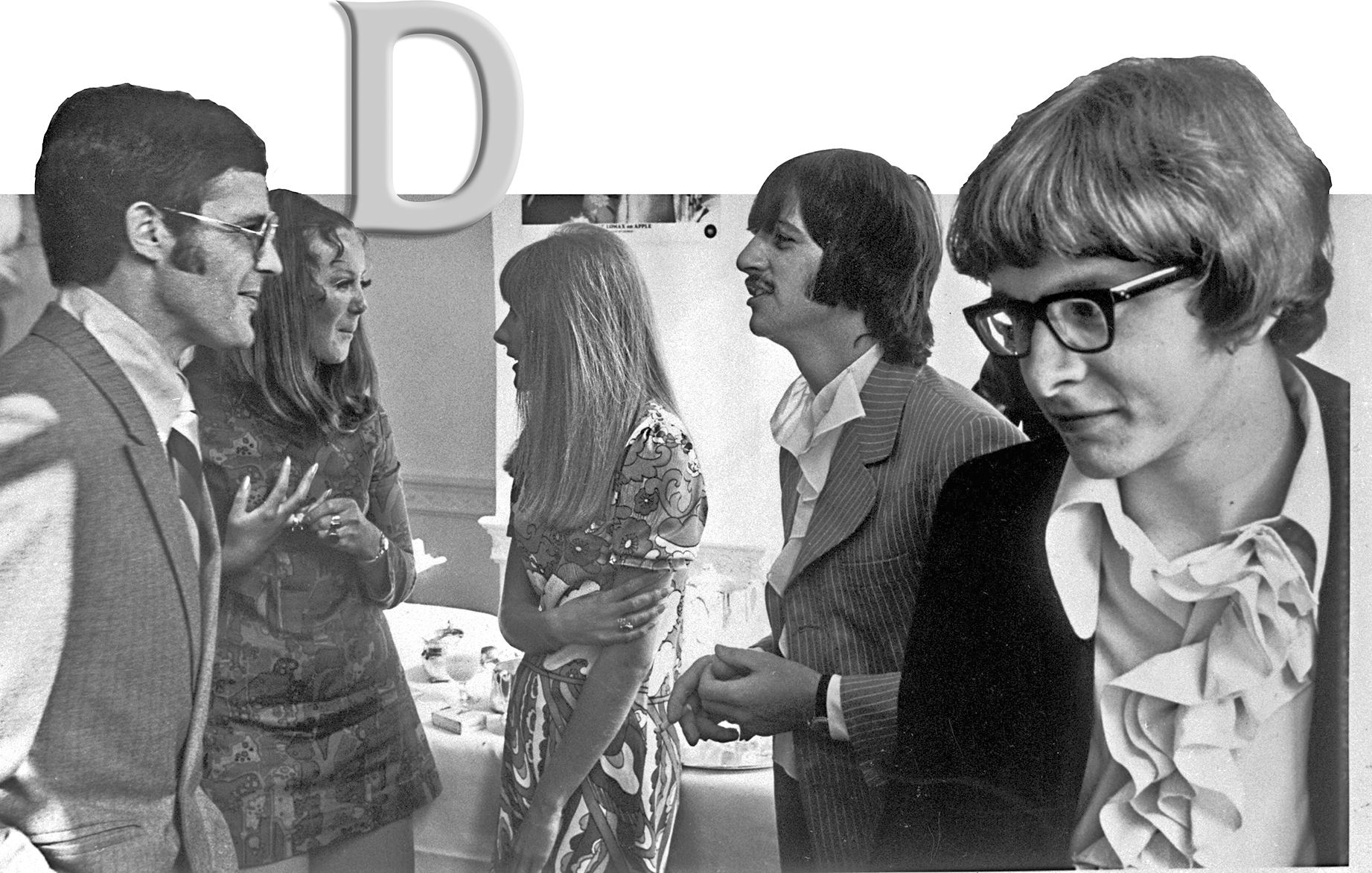

Ringo Starr and me at an Apple event, with (from left to right), Ken Mansfield of Capitol Records, Carol Padden, and Barbara Bennet.

Having wet our feet with A, B, and C, we are now ready to plunge into the rest of the alphabet. Next up is the letter D.

The first D song that I’d like to explore is a real favourite of mine. A great guitar riff, a great song: “Day Tripper.” Starting off the song and repeated throughout is an R&B-flavoured lick that the Beatles invented. To my ear, it owes a bit to the riff in the Temptations’ song “My Girl” (written by Smokey Robinson and Ronald White) that we all love so much (and many of us learn to play pretty early in our guitar-playing journey), but the “Day Tripper” motif has an extra sting in its tail as it ends with a very cool extra couple of notes. I love the way they both have the same kind of effect, though I don’t know if that was what the Beatles were consciously doing. Probably not, but I love those kinds of riffs, and they played it really well. That song, by the way, was half of a single, the other side of which was “We Can Work It Out.” I am not even sure which was the A-side or which was the bigger hit. Two great songs for the price of one.

Of course, the lyrics to “Day Tripper” were very much discussed. In England, day tripper has a fairly specific meaning: somebody who goes on a one-day vacation. One takes a day trip (often to the seaside) and comes back the same night. The term is not as common in the U.S., but the meaning would be the same. So she is just a day tripper, only here for the day. Now since that time, of course, all kinds of drug connotations have been attributed to the song, but I simply do not know for sure whether such attribution is correct—I strongly suspect not, because it was a bit early for the term tripping to mean anything other than a physical trip down to the seaside.

What I do know is that Paul was delighted by another aspect of the lyrics, which was the phrase “She’s a big teaser.” He very specifically took pleasure in the fact that, phonetically and at a quick listen, this line could be mistaken for another phrase, one that describes more specifically a woman who may appear to be promising physical delights—a promise on which she eventually decides not to deliver. A big teaser indeed!

Now, of course, to make your day tripping much easier, it would really help if you didn’t have to drive yourself there, and that’s why you need a driver.

But while I believe “Day Tripper” to be a mostly Lennon song that McCartney helped finish, “Drive My Car” was the opposite; it was mostly a Paul song that John helped him finish. “Drive My Car,” oddly enough, has also apparently been said to contain subtle sexual references—that whole “You can do something in between” and “I can show you a better time” and maybe even driving your car is a metaphor as well, who can say? Paul has talked in print about some of those references being sexual in nature. But what isn’t? This is rock and roll, after all, and “Rock Around the Clock” was not really about dancing.

A fantastic cover version of “Drive My Car” recently came to my attention. I had not heard it before, I must confess, and I found it on the Late Show with David Letterman. It is by Sting, with a woman called Ivy Levan, with whom I was not familiar, but she is an amazing singer, as well as looking quite remarkable. I was very impressed by this version. What also caught my eye is that a friend of mine, Mike Einziger, a terrific guitar player who is in the band Incubus, is the guitarist in the band on this occasion and plays a killer solo. The video is well worth finding online.

George Harrison had a lot to do with the arrangement and some of the cool guitar licks that are in the original “Drive My Car,” and he wrote some great D songs himself. One of my favourites is George’s first songwriting credit for the Beatles, “Don’t Bother Me.” That was George in a kind of “I want to be alone” mood, telling us, “Don’t come around, leave me alone, don’t bother me.” Don’t talk to me, in effect. Seriously, though, we only wish we still could talk to him. Of course, we all miss George so much as a musician, as a friend, as a composer, and as an entirely remarkable and brilliant man.

That was the first three Beatles, and last but by no means least, let us take a look at Ringo and the world of D. It so happens that Ringo, like George, wrote a song that began with D as his very first songwriting credit for the Beatles. A song called “Don’t Pass Me By,” featuring Ringo in a kind of country mood as he often was, with fiddle played by Jack Fallon—and Mr. Fallon has an interesting and remarkable story to tell. He was born in Canada in 1915 and began playing classical violin at a very young age—but switched to double bass when he was twenty years old, played in a dance band in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the war, and settled in Britain after his discharge. He played bass with all the greats of the British jazz scene (Ronnie Scott, Ted Heath, and others) and even with visiting international legends like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Django Reinhardt. He also became a master of the bass guitar, an instrument rejected by many old-school double bass players. His Beatles connection was unrelated to what he had in common with Paul McCartney instrumentally but rather relates to the fact that he was also an entrepreneur, booking gigs for various bands, including the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. So somehow Jack Fallon ended up back on violin (stylistically, it would be more accurate to say “fiddle,” I guess) while Paul McCartney played bass guitar as well as piano, and Ringo played drums, sang, and added a whole bunch of percussion on a Beatles recording session in 1968. Fallon was clearly one of those rare and valuable musicians without musical prejudices and possessed of genuine versatility—his fiddle part has a charmingly loose old-timey flavour and wobbly intonation which works perfectly with the strange piano sound (they fed the piano through a Leslie speaker) and fits in with the overall quirky oddness of the track. I like it.

So, having examined D songs written by John and Paul and George and Ringo, let’s turn to a D song that none of them wrote but which they clearly all admired. It is a great rock and roll song, heavily influenced by the blues, as is so often the case, which the Beatles often performed live: “Dizzy Miss Lizzy.” It was written and first recorded by Larry Williams, and the Beatles did an excellent cover in one of their BBC sessions that is worth tracking down.

Let us put song titles aside for a minute and look at other things that the letter D can stand for. And among the most important D things in the world of rock and roll are drums and drum fills and drummers.

So we are going to focus on Ringo for a bit. My admiration for his drumming is profound and well known. I talk about it a lot. His drumming was creative and brilliant and changed music and specifically changed the nature of rock and roll drumming forever.

When people hear a great drum sound (or any great instrumental sound) on a record, they often ask detailed questions. What kind of drums did he use? What kind of sticks? How did they mic the snare? How did they record it? I shall tell you that in most cases, with great musicians on any instrument, none of that is as relevant as who is playing in the first place.

Once, when I had the pleasure of working with Eric Clapton on a track, I was greatly concerned about providing whatever kind of amp or setup would make him happiest. His answers to my specific questions on the topic were very vague—and it turned out he was right. It really didn’t matter what kind of amp it was. It probably didn’t even matter what kind of guitar it was. He plugged in; he sounded like Eric Clapton. And I can tell you from experience that when Ringo sits down at a drum kit, it is the way he plays—the way he hits the hi-hat, the way he does his weird backhanded fills, because he is a left-handed drummer on a right-handed kit—that makes the sound and the groove immediately unique and remarkable.

I’d like to take some time here to call attention to some of Ringo’s classic and most legendary drum fills. I have decided to start with one of the great Beatles records of all time, which features some of Ringo’s best fills. It’s the classic song from the Sgt. Pepper album, “A Day in the Life,” itself a bit of a D song with Ringo’s great drumming on it and those amazing fills which are so cool and thumpy and weird. While some drummers tend to fill every tiny moment in the bar when given a space for a fill (a tradition Keith Moon maintained brilliantly), Ringo developed a style in which the fills were quite specific (as if written), with each beat beautifully placed in just the right spot. In “A Day in the Life,” if you listen carefully to the drum fills that start after the line “He blew his mind out in a car” and continue to fill the second bar of each two-bar phrase after the vocal line ends—after “the lights had changed” and after “stood and stared”—you will hear what I mean. The drums then play around the vocal itself for a moment before resuming their responses after each line of the lyric. Brilliant stuff and extraordinarily innovative. Ringo starts each fill on the snare (itself unusual—most drummers would head for a tom-tom first), but each one is different and perfect for the space it occupies.

In early rock and roll, the drum fills were often a little less carefully crafted and a little more frantic but also kind of cool anyway. And indeed, Ringo himself on some of the early Beatles records did some really interesting, if less “composed,” fills. Among my favourites of the early examples of a Ringo fill is “Thank You Girl.” I particularly love the ones near the end after the “oh, oh, oh” bits. It kind of goes “oh, oh” rum diddly um bum bum, and then repeats pretty much the same fill, but with a further slight variation. So when you next listen to “Thank You Girl,” you can also thank Ringo.

One can find great drumming throughout the entire Beatles catalogue. It is very hard to choose. But one particular drum fill that should be included on any list of great drumming moments throughout the Beatles world is on “With a Little Help from My Friends”—a song Ringo also sings, of course. The fill between the first two verses is irreplaceably perfect—we have heard it so many times that we take it for granted, but give it another listen. It is deceptively simple yet exactly right. No one else plays anything during that two-bar gap, and Ringo, using only toms this time, keeps the groove going, makes a musical statement, and builds our anticipation of the next verse all at the same time. Also worth noting is that for the rest of the song he plays only straight time, leaving the syncopation between vocal lines to Paul’s brilliant (Beach Boys–influenced?) bass part, with that great skippy rhythm to it.

The Beatles were not only incredibly successful, they were and remain wildly influential as well. Just as fans tried to emulate the clothes or the hair, musicians listened to every note that each of the Beatles played and studied every musical detail.

Ringo’s drum fills, where each note is precisely in the right place, not simply a random acceleration of drum craziness but an actual part, changed the way drums got used on rock and roll records. And the records I made were no exception. An album I produced, James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, included the song “Fire and Rain,” which became a big hit. If you listen to that song, you may notice a certain similarity between the fills that the amazing (and now legendary) drummer, my dear friend Russ Kunkel, plays on “Fire and Rain” to the fill Ringo plays on “With a Little Help from My Friends.” And that is no coincidence. Russ was influenced by the Beatles and so was I. Proudly so. We were not aiming to copy Ringo, but there is no doubt that his style affected our thinking. Russ came up with a perfect variation, and we decided to use brushes instead of sticks—but Ringo’s influence is still audible.

When it comes to Ringo’s great drumming and his brilliant drum fills, another favourite of mine is “She Said She Said,” from Revolver. I had almost forgotten about it until I heard it again recently; it has such amazing drumming throughout. It is suffused with little fills through the whole song. Ringo plays swung sixteenth notes throughout, which gives the song a great deal of the amazing groove that drives it along so well.

“She Said She Said” is also a Beatles song that has an acid-related connotation. Apparently, Peter Fonda was the one who came up with the line “I know what it’s like to be dead.” He shot himself in the stomach accidentally and thought he might be dying, but fortunately he was not. He lived to tell the tale—and included the phrase “I know what it’s like to be dead” in the telling of it during a communal LSD trip, much to John’s annoyance. John said later, “We didn’t want to hear about that! We were on an acid trip and the sun was shining and the girls were dancing and the whole thing was beautiful and sixties, and this guy—who I really didn’t know; he hadn’t made Easy Rider or anything—kept coming over, wearing shades, saying, ‘I know what it’s like to be dead,’ and we kept leaving him because he was so boring!… It was scary. You know … when you’re flying high and [whispers] ‘I know what it’s like to be dead, man.’” It was John who came up with the line, “And she’s making me feel like I’ve never been born.”

We shall end our Ringo drum festival by considering one more song, a brilliant song with an astonishingly inventive bass part and an extraordinary drum part. It shows Ringo at his most creative, his musical collaboration with Paul perfectly executed—and that song is “Rain.” The way Ringo uses his hi-hat as part of the fills is just extraordinary. And the drum sound is remarkable on that track, too. I understand the whole song was recorded at a faster tempo, and then they brought the pitch and the tempo down. That is one reason those drums sound so deliciously big and thumpy.

Turning back to song titles, we find another excellent Beatles song that begins with the letter D, the legendary “Doctor Robert”—about one of those doctors who overprescribe and give you just about anything that you think you want rather than what he thinks you need. Such doctors still exist today, of course. Indeed, the opioid epidemic from which America is currently suffering is no doubt due to a large number of Doctor Roberts all over the place prescribing fentanyl and other creepy stuff to people who don’t need it but want it nonetheless.

There’s also a trio of D songs that are all about asking a woman to do something or to get closer—or both. The first is “Dear Prudence,” for which we have been told the story behind it. Prudence was the sister of the actress Mia Farrow, and they were all in Maharishi world in Rishikesh. Prudence would not come out of her room or something like that, and John wrote the song to tempt her into the outside world. I was not there, but that is the story. The song is also a homage to Buddy Holly’s “Raining in My Heart,” which contains the lyric, “The sun is out, the sky is blue,” which John changed to “The sun is up, the sky is blue.” His admiration for Buddy Holly and his lyric writing comes through, and there is certainly no higher compliment than when John Lennon borrows your words!

The second of this trio of D songs is one of two records officially credited to “The Beatles with Billy Preston,” the B-side of “Get Back,” “Don’t Let Me Down.” It was recorded at Trident Studios, not at Abbey Road, and I understand that Mal Evans and Jackie Lomax are on background vocals, which is pretty cool. In this song, John is imploring Yoko not to let him down, and of course she did not and she has not.

And the third of the trio is less imploring and more of an enticement, “Do You Want to Know a Secret” An excellent early Beatles record—written by John, sung by George, and later covered by Billy J. Kramer. Apparently, John was inspired by the memory of his mother singing to him the Disney song “I’m Wishing,” which itself opens with the lyric “Want to know a secret? Promise not to tell?”

I don’t think I know any really good secrets these days, but perhaps you do. And on that mysterious note, we depart the letter D.