Table 2.1 Principles of classical Hollywood narration that characterise American cinema from 1917 to 1960.

2

Literature on Screen: Recasting Classical Hollywood Narration in Family Melodrama

Many Chinese revolutionary films, including the ‘Red Classics’, have literary origins: Song of Youth (Cui Wei and Chen Huaikai, 1959), Revolutionary Family (Shui Hua, 1961), Li Shuangshuang (Lu Ren, 1962) and Red Crag (Shui Hua, 1965) are notable examples. Sometimes debuted as series in newspapers, these original works began as ‘people’s literature’, enjoyed immense popularity, and were carefully selected, revised and censored for film adaptation. Film adaptations of literature were a consistent and dominant mode of revolutionary film-making: they revolutionised literature and literariness along with their reconception of ‘family’ as both literary trope and organised social unit. The trajectory of socialist film adaptations of May Fourth literature and post-1949 ‘people’s literature’ created a genre of family melodrama in which the dissolution, creation, and maintenance of family was a central theme. Early socialist film adaptations responded to the legacies of May Fourth literature as source materials; later socialist film invested in post-1949 ‘people’s literature’ derived from biographies and life experiences in the countryside. This shift in revolutionary temporality, from the past to the present, created cinematic prototypes and icons of the bygone feudal era and the new socialist era.

Adapting literature into film involved rethinking screenwriting and recasting classical Hollywood narration in Chinese literary terms. The literary obsession, following the May Fourth Movement, with ‘family’ – as microcosm of the nation, site of tension between tradition and modernity, and source of oppression for women – continued after 1949 in the cinematic genre of family melodrama, which negotiated with the Shanghai film-making tradition of family melodrama. In selecting the following family melodramas, which are also socialist film adaptations of literature, for close reading – This Life of Mine (Shi Hui, 1950), The New Year’s Sacrifice (Sang Hu, 1956) and Revolutionary Family (Shui Hua, 1961) – I explore how incorporating classical Hollywood narration, heterosexual romance (or the lack thereof) and melodrama facilitated the socialist propagation of work and family and the construction of a ‘family’ made up of nation and Party.1 As mass entertainment and education, a revolutionary family melodrama like Revolutionary Family offered a narrative resolution that overcame the traces of negativity in May Fourth literature.

Recasting Classical Hollywood Narration in Chinese Literary Terms: The Case of Xia Yan

In her study of wenyi (letters and arts) and the branding of early Chinese film, Emily Yueh-yu Yeh has brought attention to the ‘symbiotic linkage of literature and film’, specifically the crossover between the early Chinese film industry and ‘Mandarin Ducks and Butterfly’ literature, with a poignant question: ‘In what way was literature used to help brand cinema?’2 Yeh notes that in the 1920s, writers like Xu Zhuodai and Bing Xin emphasised the literary qualities of intertitles and advocated the film script as a piece of wenyi work – a loan word from the Japanese bungei, associated with ‘western fiction and concepts of humanism, equality, and freedom’ with cosmopolitan aspirations.3 After 1949, the cinematic and literary contributions of the Mandarin Ducks and Butterfly School made way for the left-wing revolutionary tradition in orthodox film historiography. Like the early Chinese film industry, the communist regime was invested in using literature to brand cinema, albeit in socialist and revolutionary terms. When the mid-1950s saw a shortage of film scripts, pre-1949 revolutionary literature and May Fourth literature provided ideas, plots and characters. The 1950 film adaptations of Lao She’s novella This Life of Mine (1937) and Mao Dun’s novel Corrosion (1941) are typical early socialist film adaptations, characterised by the prominence of script and dialogue. May Fourth and pre-1949 revolutionary literature provided raw material for creating readily reproducible cinematic prototypes. Adapting literature on screen established and rewrote the literary canon for the Party’s ideological needs. Like the Soviet effort to establish Maxim Gorky as the father of socialist realism with the film adaptation The Gorky Trilogy: My Childhood, My Apprenticeship, and My Universities (Mark Donskoi, 1938) – widely advertised and well-received in China in 1950 – the Chinese communist regime adapted Lu Xun’s short story ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ (1924) on screen in 1956, fashioning Lu Xun as a revolutionary writer and the father of modern Chinese literature.

Literature cannot come to life in film adaptation without a successful screenwriter. As a screenwriter, film critic and translator who traversed revolutionary cinema and its May Fourth antecedents, including the short story tradition and legacy of Republican era film-making, Xia Yan played a pivotal role in redefining screenwriting after the 1949 establishment of the PRC.4 Xia Yan’s speech on screenwriting, later published as A Few Questions about Screenwriting (Xie dianying juben de jige wenti), at the Beijing Film Academy in 1958 is one of the first systematic attempts to lay out the basic principles of screenwriting in Chinese cinema. The speech can be read as his theory of screenwriting, drawn from nearly three decades of practice as a screenwriter since the 1930s. In Xia Yan’s speech, Chinese literary conventions were reinstated to accommodate classical Hollywood narration. This discursive move, asserting long-standing Chinese literary tradition, allowed Xia Yan to adapt classical Hollywood narration without openly endorsing the Hollywood film establishment; at the same time, he legitimised screenwriting as a film art with a literary heritage.

Xia Yan listed the following motivations for his 1958 speech: (1) inadequate training in screenwriting at film institutes; (2) concerns about the quality of Chinese film; (3) ‘grammatical mistakes’ in Chinese film and its lack of purpose in the use of technique; and (4) the lack of a systematic theory of screenwriting.5 The deficiencies he observed in training, quality, purpose and theory spurred his formulation of a coherent set of screenwriting principles.

Xia Yan turned to Chinese literary tradition, specifically the novel (xiaoshuo), to establish the specificity of the filmic medium and its artistic proximity to the novel. He suggested that film resembled novels rather than stage drama because it could overcome constraints of time and space: ‘From the perspective of screenwriting, film resembles a novel rather than a play, because plays are limited by the three walls on stage.’6 The artistic aspirations of film and novels were not bounded by the theatrical stage. Xia Yan also argued for the specificity and supremacy of film over both stage drama and the novel, in terms of its expressive method and reproducibility.

Xia Yan explained that film, integrated with technology, had a unique expressive method. For instance, a film could visually depict how a character climbs a mountain with tracking, panning and close-up shots. In contrast, the same action could only be expressed in stage drama by dialogue: ‘Having climbed this far, I’m simply exhausted!’7 Film overcame the constraints of the stage, where actors exaggerated their expressions and movements for the sake of the audience sitting in the last row of the theatre. Film, unlike stage drama, could employ camera movements and shot ranges – close-ups, medium shots and long shots – so that the entire audience could see clearly from every angle.

Along with asserting film’s unique expressive method, Xia Yan emphasised its reproducibility and popular appeal, which other artistic forms could not surpass. A well-known novel could reach several hundred thousand to several million educated readers; but a film could reach an audience of millions among the working masses.8 Because of its reproducibility and unique method of expression, distinct from stage drama and the novel, film was a powerful medium, harnessed by screenwriters such as Xia Yan.

Yet in establishing the specificity and superiority of the filmic medium compared to other artistic forms, Xia Yan nonetheless drew from the Chinese literary tradition to establish screenwriting as an art. His theory reimagined Chinese literary conventions to accommodate classical Hollywood narration. At the same time, classical Hollywood narration was recast and explained in Chinese literary terms. The reinstatement of Chinese literary conventions allowed Xia Yan to identify those conventions with classical Hollywood narrative techniques in order to maintain the clarity and comprehensibility of narrative film for a rural mass audience.

A few words about classical Hollywood narration and its influence on Chinese cinema are necessary here. The principles of Hollywood narration can be summarised in terms of narrative structure, editing and the logic of spectatorship. Here I largely follow the concept of classical Hollywood narration that characterises American cinema from 1917 to 1960, as outlined by David Bordwell (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Principles of classical Hollywood narration that characterise American cinema from 1917 to 1960.

The influx and popularity of Hollywood movies in semi-colonial Shanghai since the 1910s demonstrated that Hollywood cinema as a culture industry influenced Shanghai cinema. By the 1930s, Shanghai film-makers had mastered the narrative principles and stylistic devices of classical Hollywood narration. Xia Yan mentioned the many Hollywood films he saw when he first entered the Chinese film industry, as a screenwriter in the silent era:

When I first entered the film industry, there were no formal film scripts. There were only two words in what we called a ‘scene description’ (mubiao): ‘entrance’ and ‘departure’. It was in the silent era, when dialogues were not written in film scripts. Actors improvised according to the directors’ demands and guidance […] There were very few books on film and I couldn’t read Russian. What I read was translated from Japanese and English. Watching film was the primary way for me to learn.13

As a screenwriter for the silent film Spring Silkworms (Cheng Bugao, 1933), adapted from Mao Dun’s original 1932 novella, Xia Yan wrote the story of Old Tongbao’s family and its downfall in accordance with the popular genre of family melodrama by using classical Hollywood narrative technique. The film adaptation uses chronological narration to depict the family’s rearing of silkworms, which is intertwined with and dependent on seasonal change as well as the struggling rural and national economy of the 1930s. Echoing a Chinese saying, ‘the whole year’s work depends on a good start in spring’, the film begins in springtime, not long after the Qingming Festival. It proceeds chronologically through the stages of production: hatching, feeding, cocooning and harvesting. Running out of mulberry leaves, and the closure of silk factories due to Japanese invasion and competition from foreign-owned silk processing plants, function as narrative deadlines typical of classical Hollywood narration and melodrama. The former forces Old Tongbao to take a loan and go into debt; the latter forces him to sell his harvest at a loss. Each step of silk production propels the narrative forward chronologically, while setbacks derail the sale of the harvest as a narrative resolution to the family melodrama.

The film adaptation of Spring Silkworms employed continuity editing to portray the delicate day-to-day growth of the silkworms from larvae, feeding on mulberry leaves on trays, to silkworms spinning silken cocoons on twigs. Although the film is predominantly about one family’s superstition and work ethic in a rural economy, marital strife and heterosexual romance form a subplot that conveys the plight of women and generational conflict, as the young characters question the superstitious and stubborn behaviour of the old.

Xia Yan’s experience of screenwriting for film adaptation in the left-wing Shanghai film-making tradition made him an ideal candidate for screenwriting socialist film adaptations such as The New Year’s Sacrifice, The Lin Family Shop (Shui Hua, 1959) and Revolutionary Family. In his 1958 speech on screenwriting, he highlighted the importance of conciseness and clarity in chronological narration, the prominence of the protagonist and the maintenance of continuity. Xia Yan emphasised film as a one-time experience – unlike literature, where one can flip the page and re-read from the beginning. Therefore, clarity was especially important in screenwriting.14 He described film as the most ‘concise’ (jinglian) art, the purpose of which had to be made ‘clear’ and ‘explicit’ for the audience.15

Xia Yan’s vision of clarity in filmic narration implicitly subscribed to classical Hollywood principles, while at the same time explicitly turning to the Chinese literary tradition for theoretical guidance: ‘Chinese poetry, fiction, and drama have common characteristics: beginnings and ends, clear narration and clear layers.’16 Reverse narration, Xia Yan said, would confuse the rural mass audience. Chronological narration was facilitated by voice-over narration, which supplied story background in the opening of a film. Xia Yan traced this literary convention to Peking opera and Yuan drama: ‘In Peking opera and Yuan drama, fumo represents the voice of the author and tells the summary of the story.’17 In the 1956 film adaptation of Lu Xun’s short story ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’, screen written by Xia Yan, an extra-diegetic narrative voice introduces the protagonist Xianglin Sao. Like classical Hollywood narration, which seldom acknowledges its own address to the audience except at the beginning and ending of a film, Xia Yan encouraged explicit address to the audience in a film’s opening, in order to maximise clarity and comprehensibility.

In accord with classical Hollywood narration featuring goal-oriented protagonists, Xia Yan suggested that the filmic image of the protagonist had to be ‘distinct’ (xianming), so as to arouse audience interest.18 He argued that in film, the protagonist must appear first – in contrast to Chinese drama, where supporting characters could appear first. The beginning of a film had to introduce the social backgrounds of and relationships between characters with maximum clarity. Xia Yan used the Chinese term ruxi, which literally means ‘being immersed in the play’, to describe how a film should strive for its audience’s diegetic absorption and suspension of disbelief.19 Film should ‘very quickly arouse curiosity in the audience’ so that from the beginning ‘a question mark appears in the audience’s mind’.20 He offered the example of the Soviet film Chapaev (Georgi Vasilyev and Sergei Vasilyev, 1934) as a successful film opening that created a distinct image of the protagonist: the eponymous hero Chapaev is shown in the film’s outset as a leader, fighting courageously. In Revolutionary Family, for which Xia Yan wrote the screenplay, the revolutionary heroine Zhou Lian appears in the opening of the film, with a distinct screen image, as the protagonist and storyteller.

Echoing classical Hollywood narration’s establishment of ‘an initial state of affairs that is violated and must then be set right’, Xia Yan used the Chinese literary terms ‘qi’ (opening), ‘cheng’ (development), ‘zhuan’ (turn) and ‘he’ (resolution) to describe the flow of narrative film.21 For instance, in Spring Silkworms, each production step corresponded to the chronological structure of qi, cheng, zhuan and he in Chinese literature. He emphasised narrative causality and continuity with the literary metaphor of ‘needlework’ (zhenxian), which joined together paragraphs, chapters, scenes and sequences.22

Xia Yan compared ‘sequences’ in film to units and divisions in other literary genres: chapters (zhanghui) in the novel, turning points (zhuanzhe) in opera (xiqu), or acts (mu) in modern drama (xiandaiju). He considered the ‘paragraph’ the closest equivalent to ‘sequence’ – a term he did not translate but retained in the English original – describing a sequence as ‘a chronological order’ (shunxu), ‘a paragraph that connects’.23 He valued continuity (xianjie) between sequences and suggested that sequences in narrative film should be organised according to the chronological development of plot. At the most basic level, Xia Yan explained, a fade-in or fade-out functioned as cinematic punctuation, dividing a film into sequences.

The theory of screenwriting found in Xia Yan’s 1958 speech implicitly recast classical Hollywood narration in Chinese literary terms, while explicitly asserting the importance of Chinese literary tradition and its related arts such as opera and drama. These rhetorical and theoretical moves allowed Xia Yan to synthesise classical Hollywood narration and Chinese literary convention without openly subscribing to the former.

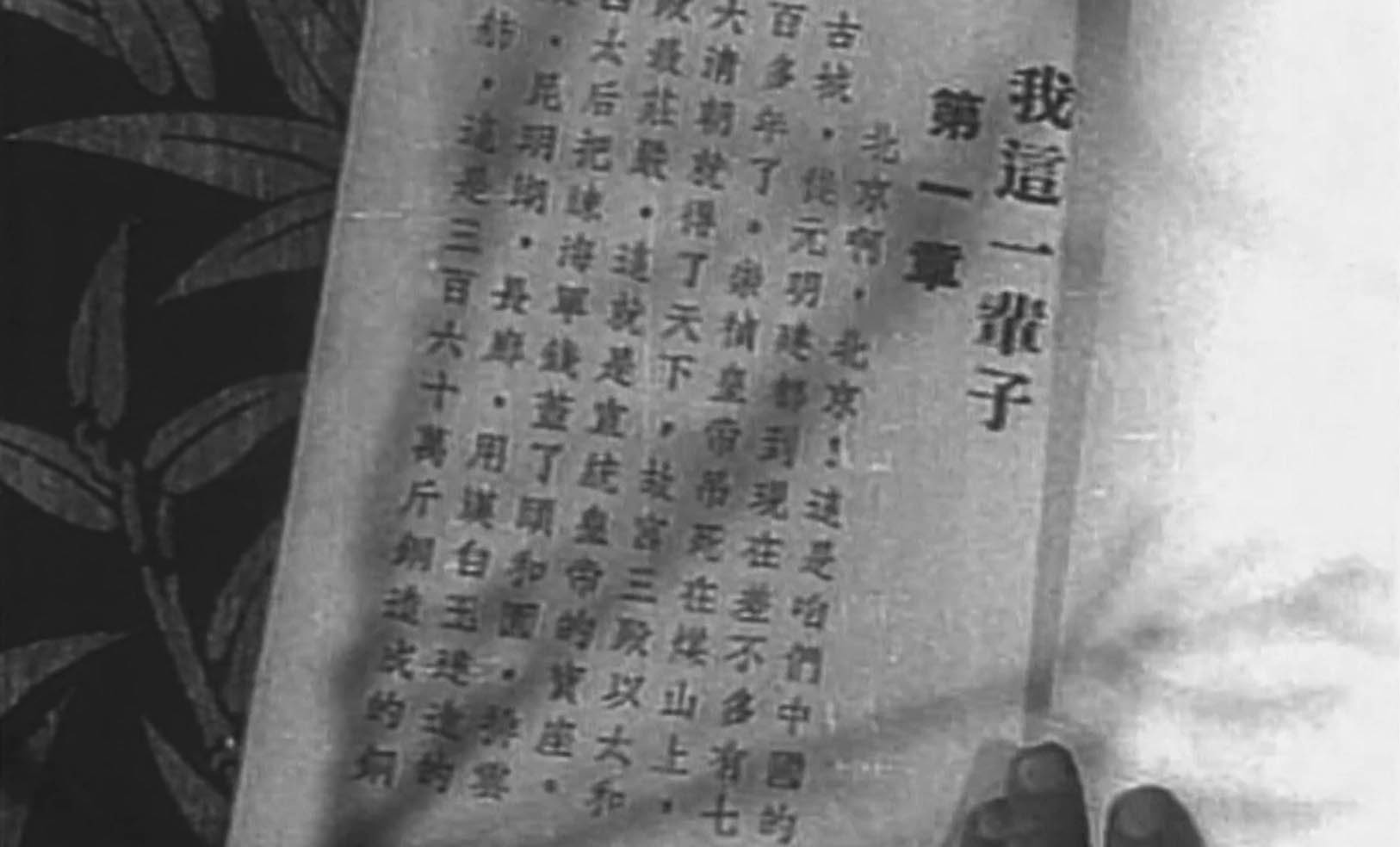

This Life of Mine

Given its engineered popularity and canonical status, the 1950 film adaptation of Lao She’s novella This Life of Mine (1937) is a suitable point of departure for examining the representation of family in early socialist film adaptations of literature. This Life of Mine achieved the best box office of the eight films released during the New Year holiday in 1950. The film demonstrates characteristics of classical Hollywood narration: chronological narration, a prominent protagonist and continuity editing. Yet though its narrative structure is largely chronological, This Life of Mine begins with an explicit address to the audience in the form of a first-person reverse narration to maximise clarity and retain the literary quality of the original. Like the novella, the film begins with the protagonist’s reminiscence of his life. The prominent voice of the protagonist–narrator is spoken over the filmed act of flipping the pages, which functions throughout the film as a cinematic punctuation that divides the film into sequences (Figure 2.1). The literary quality and aura of written words are transformed and made comprehensible through voice-over narration and direct address to the audience.

Figure 2.1 The physical act of turning the pages, accompanied by the off-screen voice of the protagonist–narrator, functions as a cinematic punctuation that divides the film into sequences.

This Life of Mine strives for clarity in its opening by presenting a distinct image of a protagonist in crisis. Its combination of voice-over narration and medium shots compels the audience to identify with the goal-oriented protagonist, who tells his stories as the narrative unfolds. Because of the first-person reverse narration in the opening of the film, a question mark appears in the mind of the audience and propels the narrative forward: What is ‘this life of mine’ that the protagonist wants to tell?

In adapting the forms of classical Hollywood narration, the narrative of This Life of Mine undergoes considerable modification. Unlike the dual plot of heterosexual romance and work typical of classical Hollywood narration, This Life of Mine alternates between the protagonist’s work and family life. Succeeding the opening first-person reverse narration, the chronological development of the protagonist’s work and family life follows the plot of the original novella, telling of the young protagonist’s happy days when he first entered the police profession, a respectable occupation that provided him a stable income and job satisfaction. The film adaptation continues with the protagonist’s witnessing of the Boxer Rebellion, the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the April Fifth movement, the Japanese invasion and the Civil War between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party (the Japanese invasion and Civil War are absent in the original novella). Yet no change of government brings peace or prosperity. Ironically, the protagonist, a policeman whose duty is to maintain law and order, can do nothing but turn a blind eye to corruption and violence throughout decades of turmoil.

The film adaptation creates a dramatic turning point that is absent in the novella: the protagonist’s daughter is captured by the Japanese military, after which the protagonist lets his son, Haifu, join the Communist army to avenge the misdeed. At the film’s end, the protagonist is imprisoned by the Nationalists, after which he becomes homeless, walking in the snow in his final moments. Unlike the novella, in which Haifu dies of illness, the film comes to a resolution with a final shot of Haifu holding a flag in victory, over which is superimposed a map of China (Figure 2.2). The addition of this dramatic turning point, the young woman’s capture, activates anger and instils in the audience a sense of urgency and crisis, thereby facilitating diegetic absorption. It also allows the narrative to take on new political and familial value: Haifu’s commitment to the communist cause in order to avenge his sister’s capture by the Japanese becomes the key to narrative resolution, which the novella lacks. Replacing the fallen protagonist/head of the family, the Party becomes Haifu’s implied new family.

Figure 2.2 The final shot of This Life of Mine (1950).

This Life of Mine also employs stylistic devices typical of classical Hollywood narration to address pedagogical concerns such as class conflicts. The film portrays disparities between rich and poor through graphic match cuts: in a sequence where Mr. Qin’s wife complains about the lack of good shoes in the city, a graphic match between a medium shot of a table full of shoes and a medium shot of a worn-out shoe depicts the disjunction between upper-class luxury and the day-to-day reality of the poor. A sequence where Mr. Qin buys his wife a Japanese perfume is immediately succeeded by three close-up shots of a child buyer’s hand as she lays down 30 yuan on the table. The graphic match between Mr. Qin’s purchase of the perfume and the child buyer’s purchase of a baby from a poor and desperate mother establishes equivalence in monetary value but disparity in use value and exchange value. In these two examples, graphic match not only allows scenes to move seamlessly from one to another in continuity, but also communicates class contradictions and heightens dramatic effects.

Selective adherence to classical Hollywood narration and continuity editing in This Life of Mine chronicle the downfall of the male protagonist as the family head. Although the film adaptation, like the novella, does not include heterosexual romance as a subplot, its addition of a dramatic turning point (the capture of the daughter), class conflicts, and moral polarisation fulfil the entertainment and pedagogical priorities of film adaptations produced after 1949.

‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’: May Fourth Critical Realism

Lu Xun’s short story ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ (1924), a canonical work of May Fourth literature, was adapted in 1956 into a film directed by Sang Hu to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of Lu Xun’s death.24 Xia Yan and Sang Hu, the film’s screenwriter and director, described The New Year’s Sacrifice as a serious and glorious ‘political mission’.25 A contemporary commentary titled ‘The Film Script is Good; the Film is Good Too’ in Renmin ribao (People’s Daily) described the film as ‘a courageous and successful creation’ that creates ‘visual pleasure’, turning the literary work into ‘a visible filmic image’ while retaining ‘fidelity to the original’.26 This brief commentary, published as an endorsement of the film just three days after the national commemoration of Lu Xun’s death, provides a glimpse into the aesthetics and politics of film adaptation after 1949, when the creation of revolutionary art for the masses and the construction of Lu Xun’s legacy became persistent concerns of the Party.

The 1956 film adaptation was not the first adaptation of Lu Xun’s original short story. Ten years earlier, in 1946, ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ had been adapted into a yueju (Shaoxing opera) by theatre director Nan Wei, becoming a milestone in yueju reform. In 1948 Nan Wei adapted Lu Xun’s short story again, into the yueju film Xianglin Sao, starring the original cast of yueju actors, with Xianglin Sao played by Yuan Xuefen.27 In speaking of his work writing the screenplay for the 1956 film, Xia Yan recalled that because ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ had been adapted into different media several times, he could draw from previous successes and failures.28 Xia Yan therefore ‘courageously’ accepted the ‘mission’ of writing the script for the 1956 film adaptation of ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’.29

Lu Xun’s original short story was initially a work of May Fourth critical realism. Here, the multivalent and highly contested term ‘realism’ refers to aesthetic experiments often carried out in the name of revolution, a mode of storytelling and an historically contingent evaluative process. The term ‘critical realism’ refers to Lu Xun’s early experimentation with the short story by representing and mediating social reality through the ironic stance of the mediating narrator, a hallmark of his short stories in Call to Arms (1923) and Hesitation (1925), also written in the May Fourth era.

The struggle for realism was emblematic of China’s entry into modernity. Realism was a continuous thread in revolutionary artistic consciousness from the time of the May Fourth literary revolution. The May Fourth movement gave rise not only to the use of the vernacular as the medium of literary expression, but also to the translation of foreign texts that sparked experimentation with Western literary forms like realism. As Theodore Huters has suggested, realism was construed and perceived as a successive stage in an evolutionary progression of genres from classicism to romanticism; thus ‘realism became a token of faith that Chinese literature was moving forward along the universal path pioneered by Western literary practice’.30 Realism as an aesthetic experiment therefore promised a kind of social evolution and functioned as a currency accepted by what Pascale Casanova describes as the ‘world republic of letters’ dominated by the European West.31 The success of realism as a tool of social reform in the West, Huters further notes, became a model for the May Fourth intellectuals’ search for a literature that would critically engage with social reality. Realism was appealing for May Fourth intellectuals because it was believed to function as a critical window on social reality and a force for social betterment. Lu Xun, one of the pioneers of the May Fourth literary revolution, experimented with the realist short story to awaken the nation from feudal practices that produced oppressions of various kinds. The victimisation of peasants, the dissolution of family and the role of the intellectual became the persistent concerns of Lu Xun’s realist short stories.

One of the most distinctive features of Lu Xun’s critical realism was his use of ironic and ambivalent narrators to highlight the limits of realism in mediating social reality. Marston Anderson has suggested that Lu Xun was conscious of the limits of realism, and offered in his stories ‘a critique of his own method and of the realist project’: ‘the realist narrative, by imitating at a formal level the relation of the oppressor to the oppressed, is captive to the logic of that oppression and ends by merely reproducing it [my emphasis].’32 In other words, the lack of overt authorial intervention characteristic of realist narrative reproduces oppression rather than eliminating it. Similarly, David Der-wei Wang describes Lu Xun’s narratorial position as that of a ‘frustrated realist’ who worked within the limits of realism as a critical tool.33 Central to both scholars’ discussions of the limits of realism in representing reality is Lu Xun’s highly self-conscious use of the narratorial position to problematise historical agency and any possibilities of positive moral actions on the part of the intellectuals as a class.

The mediating narrator ‘I’ in ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ provides an example of the critical realism Lu Xun engenders. The story begins with the narrator’s return to Lu’s town and his confrontation with Xianglin Sao, a middle-aged maid cast out by the Lu family, who questions the narrator about whether or not Hell exists. The narrative continues with the narrator’s evasion of the former maid’s question and his eventual comfort in having avoided her question with the equivocation, ‘can’t say for sure’ (shuobuqing). However, the news of Xianglin Sao’s death leaves the narrator feeling somewhat guilty, and he begins to tell readers her full story, from deceased husband to her escape to the Lu family, from second marriage to the unfortunate death of her second husband and son and ultimately her own downfall and death. The narrative ends with the narrator feeling quite at ease, amidst the sounds of the New Year celebration.

The equivocal position of Lu Xun’s ineffectual narrator–bystander throws into doubt the possibility of sympathy on the part of storytellers, listeners and readers. At stake are the usefulness of storytelling and literature in mediating social reality. The crux of ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ lies in the ironic position of the narrator who, in the process of storytelling, gradually shirks responsibility and in the end detaches himself from Xianglin Sao’s tragedy: ‘wrapped in this medley of sound, relaxed and at ease, the doubt which had preyed on me from dawn to early night was swept clean away by the atmosphere of celebration […]’34 The narrator feels like a ‘complete fool’ and ‘hesitates’ when confronted with Xianglin Sao’s question about the existence of Hell, and his answer that one ‘can’t say for sure’ is, he says, a ‘most useful phrase’: ‘by simply concluding with this phrase “can’t say for sure”, one can free oneself of all responsibility.’35 Lu Xun’s use of a non-heroic protagonist and a non-heroic narrator, his gradual unveiling of what is concealed, and the concealment of fictionality by the absence of overt authorial intervention gave the text formal characteristics typical of nineteenth-century European realism.36

However, the narrator’s non-intervention and moral vacillations also implicate the text as an accomplice in reproducing social injustice, revealing the limits of realism in mediating and acting upon social reality to cure social ills. As Anderson suggests:

[T]he ‘I’ who narrates her [Xianglin Sao’s] story is not in any direct sense responsible for her sufferings (he remains peripheral to the plot), but he has the power that she lacks to vocalize her grief, and has done so forcibly for the reader. Yet his failure to go one step further and use his power to grant meaning to her story makes him, the text implies, a guilty accomplice of the superstition-ridden society that has produced her tragedy.37

Indeed, the narrator’s act of storytelling reproduces the victimisation of Xianglin Sao. As Xianglin Sao repeats her story over and over again, dialogised by the narrator in reminiscence – ‘I was really stupid, really’ – the narrator cynically reproduces her misery: ‘she probably did not realise that her story, after having been turned over and tasted by people for so many days, had long since become stale, only exciting disgust and contempt.’38 The narrator’s recreation of the former maid’s voice and consciousness vocalises and repeats her plight, only to reproduce and perpetuate it in his own voice and consciousness. Lu Xun’s creation of multiple consciousnesses, complex narration, and refusal to provide an authoritative voice allowed him to establish an ironic, critical distance, to articulate the failure and negativity at the heart of his realist project. The text was thereby given a highly critical and self-reflexive quality: a critical realism.

The New Year’s Sacrifice: A Family Melodrama

Along with being an aesthetic experiment and a mode of storytelling, realism is also a historically contingent evaluative process. It shapes, produces and sustains specific aesthetic values and practices reinforced by institutions and individuals. Hence, in ‘Contingencies of Value’, Barbara Herrnstein Smith suggests that ‘every literary work is a product of a complex evaluative feedback loop.’39 Artistic creation functions as ‘a paradigm of evaluative activity’ that constitutes value judgements, cultural policy and acts of evaluation that are explicitly or implicitly ideologically motivated.40 The contingent variability and mutability of the term ‘realism’ as a labelling of cultural productions, including film, reveal the historically contingent evaluative process at work from the May Fourth era to the Mao era. As Huters suggests:

What seems to be a commonsensical category ‘realism’ kept escaping its ostensibly evident definition and revealing its subsets and eventual permutations – critical realism, social realism, proletarian realism, and romantic realism – taken as a whole to serve to discount the notion that realism could ever have constituted a discursive category stable enough to provide a source of positive intellectual guidance.41

The 1930s and 1940s witnessed an emerging discourse on revolutionary literature and the creation of proletarian literature and art.42 In Mao’s talk at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in 1942, he extolled and canonised Lu Xun as ‘the sage of new China’, but implicitly rejected Lu Xun’s satirical style of writing, which favoured ambiguity and irony:

The style of the essay should not simply be like Lu Xun’s. Here we can shout at the top of our voices and have no need for veiled and roundabout expressions, which are hard for the people to understand […] We are not opposed to satire in general, what we must abolish is the abuse of satire.43

In the talk, Mao attributed historical agency to proletarian literature and art, the ‘cogs and wheels’ of the revolutionary cause, which should not stop at exposing dark forces but rather go one step further to extol revolutionary struggles and ‘help the masses to propel history forward’.44 Mao’s passionate belief in historical agency implicitly opposed the ambivalent and passive stance of the mediating narrators that were a bedrock of Lu Xun’s critical realism.

Hence, socialist film adaptation of pre-1949 literature such as This Life of Mine and ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’ can be seen as a politically motivated aesthetic experiment that stretched the limits of May Fourth critical realism and social realism.45 As a consistent and dominant mode of revolutionary film-making after 1949, socialist adaptations sought to revolutionise literature by radically challenging the very notion of literariness and the value attached to it, which is posited on literacy. As a screenwriter, Xia Yan strove for popularisation (tongsuhua) because his targeted audience was no longer readers from the intellectual class but spectators from the general working masses.46

Notwithstanding the goal of popularisation, Xia Yan saw fidelity to the original as one of his missions. Yet though adaptation is different from writing an original, Xia Yan described adaptation as ‘creative labour’.47 Using the three-hour-long film adaptation of War and Peace (King Vidor, 1956) as an example, he highlighted the necessity to ‘select’, ‘extract’ and ‘crystallise’ the essence of the literary original: ‘Sometimes one has to exaggerate, reduce or supplement the original in order to turn it into an audio and visual form.’48 It is through the addition, deletion and modification of details that the film adaptation popularised the character Xianglin Sao as a feudal icon while claiming fidelity to the original.

Re-narrativisation and Temporality

As family melodrama, The New Year’s Sacrifice took on entirely new clarity, simplicity and force that were absent in the original short story. In keeping with classical Hollywood narration, the film adaptation replaced Lu Xun’s ambivalent narrator with chronological omniscient narration. Additionally, the film incorporated heterosexual romance and melodramatic shocks that fulfilled the entertainment and pedagogical demands of revolutionary cinema.

Like This Life of Mine, The New Year’s Sacrifice largely followed the method of classical Hollywood narration, presenting a logical chain of cause and effect with a high degree of narrative resolution. The New Year’s Sacrifice replaced the complex and ambivalent narrative voice in Lu Xun’s original text with a straightforward chronological narration in the celebratory voice of History. This chronological narration gave the film a new sense of clarity, rhetoricity and positivity, in line with the aesthetic needs articulated in Mao’s talk in 1942. In the film adaptation, ‘complex narrative modes were abandoned for the sake of a more readily comprehensible exposition reminiscent of traditional storytelling.’49 The film opens with the passionate voice of an extra-diegetic filmic narrator-storyteller, who gives the story of Xianglin Sao a positive beginning and a positive ending. The New Year’s Sacrifice tells Xiangling Sao’s story using chronological diegetic time, but the narrator’s voice in the opening and ending of the film retrospectively places the events in a bygone feudal temporality, therefore propelling history forward.

The film adaptation’s voice-over narration begins with an explicit address to the audience. The omniscient voice of History declares that ‘this story happened some forty years ago when the 1911 Revolution took place, a time absent in the memories of the young.’ Whereas Lu Xun’s narrator speaks of and with Xianglin Sao through dialogisation (hence his simultaneous involvement with and evasion of Xianglin Sao’s tragedy, and the resulting ironic and ambivalent stance), the film’s narrator is oriented to Xianglin Sao from the external, neutral, objective and omniscient position of History.

The opening of the film adaptation presents a distinct image of the young, energetic and healthy Xianglin Sao: a protagonist in keeping with classical Hollywood narrative. The film offers a straightforward and chronological exposition of Xianglin Sao’s kidnapping, second marriage and downfall. Xianglin Sao’s misery is not actually depicted until the end of the film, as she faces the camera and asks if Hell exists. The narrator’s evasion in Lu Xun’s text – ‘can’t say for sure’ – is completely removed, replaced by the sympathetic voice of the filmic narrator, mourning and extolling ‘Xianglin Sao, honest and hardworking,’ who ‘after much suffering and humiliation, fell over and died miserably.’ The film narrator then rejoices: ‘This happened over forty years ago. It happened long ago. We should be happy that times like that are gone for good! Such things have gone forever!’ The voice-over narration gives a positive conclusion to an otherwise tragic story, ending the film with a high degree of narrative resolution.

By declaring ‘such things have gone forever’, the voice in the film adaptation takes the spectators from one moral order (feudal and pre-revolutionary) to another – a leap of faith to the revolutionary present and implicitly utopian future. In keeping with Mao’s formulation of the goals of proletarian literature and art, the authoritative voice of the film’s narrator transforms the failure and negativity of Lu Xun’s text into positivity. It propels history forward by reconstituting the feudal past as a forever-bygone temporality. Smith has suggested that ‘we make texts timeless by suppressing their temporality’, but it is perhaps more proper to say that we make texts timeless by rewriting and reconstituting their temporality.50 By changing the literary mode into a cinematic mode of direct address to the audience, the film adaptation gives the story a sense of optimism and a positive tone free of the irony of Lu Xun’s narrator.

Heterosexual Romance and Family

Film adaptations transform the textuality of their original literary texts into a new sensuality, made possible by the filmic medium. By indulging spectators in the heterosexual romance typical of classical Hollywood narration, a number of Chinese film adaptations took on an entirely new entertainment and family value that was absent in their originals. Director Sang Hu’s collaboration with Zhang Ailing in making Long Live the Wife (1947), and his opera film Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai (1954), entertainingly represented romance and marriage on the movie screen. The New Year’s Sacrifice was not an exception in representing romantic love; many Chinese films produced at the time did so. Family (Chen Xihe and Ye Ming, 1956), adapted from Ba Jin’s historical novel Family (1933), was another notable socialist adaptation in the cinematic genre of family melodrama. The film is as much about the dissolution of the extended Gao family as it is about the tragic love stories of Jue Xin, his wife Rui Jue, Cousin Mei, Jue Hui and the maid Ming Feng, whose interactions, aspirations and mental struggles take up much of the narrative. Family is filled with sequences that portray couples in love: rowing in a boat, picking plum blossoms, holding hands and hugging. It takes place between 1916 and 1920, during the May Fourth period, when ideas about free love and resistance against arranged marriage emerged. Later revolutionary films such as Nie Er (Zheng Junli, 1959), Five Golden Flowers (Wang Jiayi, 1959) and The Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin, 1961) are now well-known for their dual plots of romance and work (as will be discussed in subsequent chapters). Here, I continue the discussion of The New Year’s Sacrifice with a close reading of how the film indulges spectators in heterosexual romance, facilitating the formation and dissolution of family on a narrative level within the family melodrama.

One of the major enrichments of plot and character development in The New Year’s Sacrifice was its expansion of the heterosexual romance and marriage typical of classical Hollywood narration. Unlike the literary text, which told the story of Xianglin Sao’s second marriage with He Laoliu in the voices of Old Mrs. Wei and Xianglin Sao herself, the film rendered the performance of He Laoliu on screen, giving him gentle gestures and a soft demeanour: a sympathetic image that is absent in the literary text. Sang Hu, the film’s director, romanticised He Laoliu as someone who ‘awakens the love hidden in the soul of Xianglin Sao’, so much so that the commentary in Renmin ribao described the morning after the blind marriage scene as ‘a most beautiful and touching scene’ that portrayed He Laoliu’s ‘love, sympathy and intimate concern for Xianglin Sao’.51 Although some contemporary critics argued that the film adaptation ‘destroyed the realism’ of the original short story, with He Laoliu ‘distorted’ into a romantic and ‘gentlemanly’ character, Li Chenglie argued otherwise, asking rhetorically: ‘why isn’t love permitted among villagers and manual laborers?’52 This debate reveals the ways in which the film adaptation transgressed the original literary text by rewriting Xianglin Sao’s second marriage as family melodrama.

He Laoliu’s visual presence is significant, for a male figure not only fulfils the narrative requirement of heterosexual romance and family life, but also makes possible Xianglin Sao’s tragedy as the victimised widow of a patriarchal feudal society. He Laoliu is a crucial figure in the film’s moral universe: without him, the tragedy of Xianglin Sao could not be realised. Their romance is depicted subtly, with minimal ornamentation, and is immediately sublimated to the higher narrative motive. For example, in one scene, the injured and weak Xianglin Sao changes from hostility to appreciation at the sight of He Laoliu, who gently and sympathetically offers her a bowl of water. The viewer sees ‘the hidden love awakening in her soul’, as Sang Hu puts it.53

The transition is conveyed through a series of shot/reverse shots and close-ups, typical Hollywood editing techniques used to convey one-on-one conversation, combat or romantic relationships (Figure 2.3). Immediately following this sequence in which the seed of love is sown is another, indirectly conveying Xianglin Sao’s pregnancy. In the initial shot of the new sequence, the couple’s manual labour is depicted in a shining and positive light. As Xianglin Sao is about to throw up, the camera cuts to the troubled He Laoliu who hesitates, slowly realises and says with a joyful smile: ‘well […] you […]’ The camera then cuts to Xianglin Sao with an embarrassed yet happy smile. Immediately following this is a shot of a baby crying (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.3–2.4 Xianglin Sao’s transformation from hostility to awakened love to the establishment of a family is conveyed in eight shots with elliptical editing.

Together, the two sequences show the whole transition from Xianglin Sao’s hostility to awakened love to the establishment of a family. This transformation is conveyed in just eight shots with elliptical editing. Hollywood conventions of heterosexual romance and ‘invisible’ continuity editing were creatively adapted to provide ‘just enough’ romantic enticement for the spectators, while narratively the romance (lian’ai) was directed to explicit goals: heterosexual union and the formation of family.54

Orchestrating Melodramatic Pathos

The May Fourth Movement’s focus on family as national microcosm, site of historic tension, and source of women’s oppression continued after 1949 in the cinematic genre of family melodrama, negotiating with the legacy of family melodrama from the Shanghai film-making tradition. A cursory look at film titles – Family, The Lin Family Shop and Revolutionary Family – suggests the persistent theme of family in socialist film adaptations of literature. As Xiao Liu suggests in her study of The Red Detachment of Women as revolutionary melodrama, the film’s historical precedent, 1930s leftist films, often ‘infuse[d] progressive political messages into popular melodramatic forms’ that drew heavily on the Buddhist notion of retribution, Mandarin Duck and Butterfly urban popular fiction, sensational crime stories and the discourse on Wenyi.55

The New Year’s Sacrifice also created melodramatic moments to accentuate class conflicts and stir spectators into pathos, thereby creating a moral universe of victims and villains. My use of the term ‘melodrama’ is not intended to define Chinese revolutionary cinema in terms of a narrative mode that originated in the context of the French Revolution and its aftermath. Rather, I use the term more broadly, to indicate a mode that accommodates a heterogeneity of local expressions.

Recent re-evaluation of melodrama as a cinematic mode has expunged the pejorative connotations – moral polarisation and strong emotionalism – formerly associated with the term, recuperating it as a ‘perpetually modernizing form’, ‘an evolving mode of storytelling crucial to the establishment of moral good’ and a fundamental mode in mainstream cinema.56 Linda Williams goes so far as to suggest that ‘realism serves the melodrama of pathos and action.’57 The melodramatic mode serves to locate and articulate what Peter Brooks calls ‘the moral occult’; that is, ‘the domain of operative spiritual values which is both indicated within and masked by the surface of reality.’58 In this sense, melodrama refers to a high dramatisation of social existence that stirs spectators into pathos so as to unveil the realm of latent moral meanings. Moral polarisation and ‘indulgence’ in strong emotionalism are means of heightening the dramatisation of social existence, unveiling the surface reality that masks the moral occult to reveal the realm of spiritual reality and latent moral meanings. The melodramatic mode in cinema can therefore be considered ‘a system of punctuation’, in Thomas Elsaesser’s words, that orchestrates emotional ups and downs and gives expressive colours to the story line.59 Both Elsaesser and Williams suggest that the melodramatic mode effectively renders patterns of social existence – domination, exploitation, morality, gender and class consciousness – in compelling visual forms of pathos and action, making them performable through a system of gesture, demeanour and musical accompaniment.

In socialist film adaptations of literature, the melodramatic mode was put into use to create a moral anchor. Mao asserted that ‘life as reflected in works of literature and art can and ought to be on a higher plane, more intense, more concentrated and more typical.’60 Melodrama, as a cinematic mode that dramatises social existence and intensifies emotions to unveil latent moral meanings, served as a highly malleable mode for the rhetorical demands of a revolutionary aesthetics that aimed to expose class enemies, extol revolutionary struggle, and propel history forward and upward to a higher moral plane.

In The New Year’s Sacrifice, the romance between Xianglin Sao and He Laoliu, conveyed mainly through elliptical editing, serves a higher melodramatic motif: the parallel deaths of Xianglin Sao’s husband and son. Their deaths occur almost simultaneously after a debt collector threatens to take their house, pushing Xianglin Sao’s misery to extremes and dramatising the tragic narrative turn. One of the most melodramatic moments of the film, the intrusion of the debt collector, is absent in the literary text. In the film, it functions not only to introduce the type of unambiguous class enemy typical of revolutionary cinema, but also to provide a deadline typical of classical Hollywood narration. As He Laoliu struggles on his sickbed, the off-screen diegetic voice warns, ‘there are wolves’, triggering a series of melodramatic moments that culminate in the death of Xianglin Sao’s son, Ah Mao – who is eaten by the wolves.

Frequent frontal close-ups of Xianglin Sao at different camera angles during the search for her son in the deep forest, together with audio renderings of echoes and wind, agitate the spectators while literally enlarging and intensifying the actress Bai Yang’s facial expressions. Commenting on her acting in the film, Bai Yang explained that since Xianglin Sao was a reticent woman, she conveyed Xianglin Sao’s emotions through the eyes rather than verbally.61 Similarly, Sang Hu spoke of strengthening the image (xingxianggan) and action (dongzuoxing) of his characters, especially when the characters were not speaking.62 The series of close-ups are particularly suited to capturing Bai Yang’s facial performance and creating melodramatic moments.

The scene of Ah Mao’s death culminates in three consecutive and highly melodramatic shots: (1) a medium shot of Xianglin Sao holding Ah Mao’s shoes; (2) a shot of bloodstains in the woods; (3) a close-up of Xianglin Sao’s shocked face, accompanied by extra-diegetic instrumental sounds that dramatise the shock (Figure 2.5). The sophisticated use of close-up, sound recording and naturalistic colour photography, along with Bai Yang’s facial performance, gives the film a compelling visual and emotional force. It is also notable that prior to filming, Bai Yang listened to the stories of the women in the village and learned how to carry heavy loads in order to imagine and situate herself in the life of Xianglin Sao. Bai explained that learning from peasant women, like her childhood experience of living as an orphan in her nanny’s house, informed her acting. She described the key to acting as ‘merging with the character in the illusionary realm as if the illusionary realm is becoming the realm of the “real”.’63 Her facial performance, informed by her study of village peasants, is accentuated by close-ups, extra-diegetic music and naturalistic colour photography, all of which give the film a melodramatic quality.

Figure 2.5 The 1956 film adaptation of ‘The New Year’s Sacrifice’, the first colour narrative film (caise gushipian) in the PRC, offered an unprecedented immediacy in visualising Ah Mao’s melodramatic death.

The film’s revision of the original literary text accentuates Xianglin Sao’s plight by rendering it as multiple shocks succeeding one after another. Again, this heightens the melodramatic mode, in which unlikely coincidence is a hallmark. In the literary text, the death of Xianglin Sao’s husband and son do not occur simultaneously; the film makes the deaths parallel for melodramatic effect. After finding her son’s body, Xianglin Sao returns home only to discover that her husband is dead too. Her discovery of her husband’s corpse is once again accompanied by extra-diegetic instrumental sounds that underscore her shock. Dramatising the Chinese saying, ‘disaster never comes alone’, the deaths of the patriarch and son leave Xianglin Sao widowed and childless: completely outside the organised social unit of family.

The film’s melodramatic renderings of the original text are further manifested in two other key scenes that, like the deaths, accentuate Xianglin Sao’s plight by creating multiple shocks. The original story did not depict the circumstances under which Xianglin Sao is rejected by the Lu family, but the film adaptation created a dramatic circumstance to show why Xianglin Sao was kicked out of the house. In the film, Xianglin Sao donates a year’s salary to build a threshold in the temple, in the hope that by letting everyone in the community trample on her, she can redeem her sin of being a widow who brings disasters. But she is fired by the Lu family during the New Year preparation after she lays her hands on the fish intended as an ancestral offering. Xianglin Sao drops the fish the moment Master Lu shouts: ‘It is no use for you even to donate one hundred strings [to the temple]! You will never redeem your sin!’

The scene is rendered in a close-up shot of Master Lu as he shouts at Xianglin Sao. The camera then cuts to a medium shot of Xianglin Sao’s colourless face, succeeded by a shot of the fish belly up, a sign of death, after Xianglin Sao drops it on the floor (Figure 2.6). The fish used for the ancestral offering, like Ah Mao’s abandoned shoe, functions as a moral symbol and a reminder of Xianglin Sao’s plight. Appearing five times during the New Year celebrations in the film, each time it reappears the fish serves both as a narrative trope recalling the days when Xianglin Sao could take part in the New Year preparation and as a marker of her present downfall.

Figure 2.6 Appearing five times during the New Year celebrations in the film, the fish used for the ancestral offering functions as a moral symbol and a reminder of Xianglin Sao’s plight.

The Controversy of Xianglin Sao’s Resistance

The film’s most controversial scene, right after she is fired and drops the fish, led contemporary audiences to debate the interpretation of Xianglin Sao’s character. Although unquestionably victimised, Xianglin Sao’s character in the film demonstrates new resonance through resistance and rebellion.

After being fired by Master Lu, the hopeless Xianglin Sao is depicted alone in the kitchen where she questions, doubtfully: ‘Can’t even the Buddha save me?’ The film then cuts to a shot of a kitchen cleaver on the chopping board, followed by a close-up shot of Xianglin Sao’s facial expression switching from doubt to resolution and a close-up shot of her hand firmly holding the cleaver. Immediately after this shot, we see Xianglin Sao in a frenzy, violently hacking away the temple threshold with the cleaver (Figure 2.7). These four shots forcefully punctuate and orchestrate the melodramatic shock of her tragedy by emphasising Xianglin Sao’s immediate transition from hopelessness and doubt to resolute revenge against religious authority.

Figure 2.7 The film adaptation’s most controversial sequence: Xianglin Sao in a frenzy, violently hacking away the temple threshold with a cleaver. This sequence, absent in the original literary text, led contemporary audiences to debate the interpretation of Xianglin Sao’s character.

When the caretaker of the temple tries to stop Xianglin Sao by asking, ‘how could you provoke the Buddha?’ Xianglin Sao is portrayed in a low-angle medium shot as she responds, ‘the Buddha!’ The shot is then dramatically and rhythmically intercut with three low angle shots of the temple gods, again accompanied by extra-diegetic instrumental sounds, emphasising superstition and false authority (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 The added scene at the threshold of the temple was seen by some critics as a politically motivated violation of the short story’s realism, while director Xia Yan and lead actress Bai Yang said it depicted Xianglin Sao’s impulsive emotional explosion.

The scene at the threshold of the temple was not in the original literary text. It was added on the spur of the moment by yueju director Nan Wei for the yueju film Xianglin Sao. Yuan Xuefen (the yueju actress playing Xianglin Sao) agreed to the scene for the sake of ‘voicing the audience’s frustrations’ – though initially hesitant about the decision, as she later recalled. Yuan felt that the addition of that scene made the film ‘superficial in terms of its message’.64 Xia Yan, however, recollected that every time he watched the scene, he was stirred and did not feel that anything was awkward or out of sync with Xianglin Sao’s character.65 Xia Yan therefore retained the scene in his script for the 1956 film adaptation. On its release, film critic Lin Zhihao described the scene at the threshold as ‘unrealistic’, for it implies ‘a break with religious authority’ – a break with an ideology that has thousands of years of history.66 Lin asserted that the scene violated the development of Xianglin Sao’s character and that her break with religious authority was inconsistent with her question about the existence of the soul after death.

In response to criticism like Lin’s, which saw the added scene as a politically motivated violation of the short story’s realism, Xia Yan, quoting Lu Xun’s original text, argued that Xianglin Sao is a defiant character despite her weakness and superstition:

But Xianglin Sao is quite a character (chuge) […] We go-betweens, madam, see a great deal. When widows remarry, some cry and shout, some threaten to commit suicide, some won’t go through the ceremony after they have been carried to the man’s house, and some even smash the wedding candlesticks. But Xianglin Sao was extraordinary (yihu xunchang).67

Similarly, film critic Li Chenglie argued that Xianglin Sao was a strongly resisting character, as seen in her early escape and later resistance to second marriage. Li went so far as to suggest that Xianglin Sao’s hacking of the threshold was a continuation of that resistance.68 Xia Yan described that action as an ‘emotional explosion out of extreme disappointment and pain’, differing in nature from a rational awakening leading to a break with religious authority.69 Similarly, Bai Yang described Xianglin Sao as a complex character who seemed weak but was also strong, as evidenced by her early escape and resistance to her second marriage. Master Lu’s words ‘you will never redeem your sin’ shattered her spiritual pillar, Bai Yang argued, and hacking the threshold ‘is an impulsive act rather than a rational enlightenment’.70

While both takes on Xianglin Sao’s character claimed fidelity to the original short story, clearly the subtleties of her personality offered new interpretative possibilities because of the melodramatic shocks the film registered. Whether Xianglin Sao is defiant and resistant is of secondary importance to the way Xia Yan’s aesthetic experiment in screenwriting gave her a complex cinematic afterlife. Through re-narrativisation and the incorporation of heterosexual romance and melodramatic shocks, the 1956 film adaptation eliminated the ambivalence, negativity and failure that lie at the heart of Lu Xun’s critical realism. To recall the commentary in Renmin ribao, what was considered as ‘retaining fidelity to the original’ can be read as a significant rewriting and even transgression of the original. The ambivalence, complexity and self-reflexive quality of the original literary text were lost in transferral to a different ideological system, replaced by a new positivity, sensuality and rhetoricity specific to the filmic text. In the name of fidelity, the film adaptation displaced the literary conventions of the original, rewriting the text as a family melodrama in the filmic medium, redefining the character Xianglin Sao as a prototype of pre-revolutionary society and remaking Lu Xun into a revolutionary writer.

Revolutionary Family

Xia Yan also served as a screenwriter for Revolutionary Family (1961), another socialist film adaptation in the cinematic genre of family melodrama. Unlike earlier adaptations that had adopted May Fourth and pre-1949 revolutionary literature as source materials, Revolutionary Family turned to post-1949 ‘people’s literature’, typically derived from biographical memoirs and life experiences set in the countryside. In her study of this early Maoist ‘people’s literature’, Krista Van Fleit Hang suggests that ‘most narratives, after being deemed politically correct, took on second, third, and fourth lives in different forms. These travelling narratives were so effective that the revision of stories in at least one form was the norm of cultural production.’71 Her observation holds true for Revolutionary Family, adapted from Tao Cheng’s autobiography My Family (Wode yijia, 1958).

Tao Cheng (1893–1986) was a woman from Changsha, Hunan. In 1911, she was married to a young student, Ouyang Meisheng, through arranged marriage. Although she had never received formal education, Tao participated in underground work for the Communist Party with her husband in Wuhan and Shanghai starting in 1927. In 1928, Tao’s husband died from illness and overwork. The widowed Tao raised six children to become revolutionaries; her eldest son died during a mission in 1930. After 1949, Tao continued to work in various administrations, ministries and courts. In 1956, with the encouragement of Xie Juezai, Tao orally narrated her autobiography for publication by the Workers’ Press in 1958. Six million copies of My Family were printed, and it was widely circulated. Tao’s story was adapted into a film in 1961, directed by Shui Hua in his second collaboration (following The Lin Family Shop) with screenwriter Xia Yan.

Revolutionary Family replaced the extra-diegetic voice-over narration of earlier socialist film adaptations with a first-person narrator: an endearing granny tells the story of her family, shown in flashback, to a group of children. Unlike This Life of Mine, in which the old male protagonist unhappily recalls his family story, Revolutionary Family offered a distinct and positive screen image of a female family head. Played by Yu Lan, the heart-warming grandmotherly Zhou Lian became the screen persona of autobiographer Tao Cheng, whose personal experience and real-life story lent authenticity to a film invested in the truth value of the Party’s role as family. Through the figure of the grandmother, the oral tradition of storytelling replaces the literary act of flipping the pages. The film’s pedagogical priority, to mould its ideal audience into revolutionary subjects, is captured in the group of children encircling the maternal and nurturing figure while taking in her story about the Party.

For the first few minutes of the film Zhou Lian’s story is told in the form of a flashback. Chronological narration takes over, loosely following the organisation of the original autobiography and the structure of classical Hollywood narration: Zhou Lian’s marriage to Jiang Meiqing is followed by their establishment of a nuclear family with three children (Liqun, Xiaolian and Xiaoqing), and family life (rather than heterosexual romance) and the couple’s underground work form a dual plot. Work and family are mutually interdependent, demonstrating the coexistence of the socialist work ethic and the family ethic. In revolutionising the family as a social unit, the film incorporates two major melodramatic shocks: the deaths of father Jiang Meiqing and eldest son Liqun for the greater revolutionary cause. The tragic death of the male family head does not dissolve the family (as it did in The New Year’s Sacrifice); instead, it leaves behind a revolutionary legacy to be carried on by the single mother and living children.

On a narrative level, the death of the father Jiang Meiqing allows single mother Zhou Lian, with the help of her teenage son and daughter, to step in as breadwinner and moral anchor, reconfiguring the nuclear family into a revolutionary family under the Party’s wing. After Jiang Meiqing’s death, the family moves to Shanghai, losing all connexion with the Party. The teenage son and daughter, Liqun and Xiaolian, volunteer to take up the breadwinner role by working in a factory while single mother Zhou Lian stays home to take care of the youngest son, Xiaoqing. This new division of labour within the singly parented nuclear family allows the teenage son and daughter to seek and develop a new support network that, through a melodramatic coincidence, returns the family to the Party’s guidance. Liqun’s coincidental encounter with a union leader at the factory brings the narrative full circle: the family finds an old friend of his father, and by extension, the Party. From this point onwards, the Party takes on the role of benefactor–father to the displaced family.

Liquin’s eventual melodramatic death as a revolutionary martyr demonstrates the way the socialist work ethic overcomes biological kinship to form a new socialist family ethic. In a second melodramatic scene, Zhou Lian and her soon-to-be-executed eldest son encounter each other in prison, but refuse to admit their mother–son relationship so as not to betray the Party. In the end, Zhou Lian is rescued by her colleagues and the film ends with a family reunion between Zhou Lian and her two remaining children, Xiaolian and Xiaoqing, who go on to become revolutionaries in Yan’an. The film closes on the appealing face of Zhou Lian, maternal storyteller and revolutionary heroine, who passes on her story to the ideal audience: the Party’s offspring and potential revolutionary subjects.

In her analysis of The Red Detachment of Women as revolutionary melodrama, Xiao Liu suggests that the ‘nonkinship-based sisterhood’ between Qionghua and Honglian reflects the ‘imaginary’ of a revolutionary family ‘based on collective labour [in] a new regime of morality and human relations’.72 In a similar vein, Revolutionary Family offers an imaginary of a revolutionary family with a socialist work and family ethic that transcends biological kinship. As Liu argues, the role of ‘family’ in earlier 1930s Shanghai melodrama films was ambivalent: ‘on one hand, the disintegration and alienation of kinship becomes the most pathetic accusation against social disparity; but on the other hand, the proposal of kinship as the resolution to social conflicts is problematic.’73 For instance, although Twin Sisters (Zheng Zhengqiu, 1933) employed the narrative trope of twin sisters who have been split from each other for many years as a protest against social disparity, the final family reunion as a narrative resolution is a return to the status quo.

This Life of Mine, one of the first socialist film adaptations of May Fourth and pre-1949 revolutionary literature, challenged the closure in the original literary text by offering Haifu an implicit new home and family in the communist army. The New Year’s Sacrifice redefined Xianglin Sao as a feudal icon in a forever-bygone era. Family, on the other hand, retained author Ba Jin’s accusation against family and the feudal system. This protest is most vehemently voiced by the character Jue Hui, who says, ‘I hate this family’ and ‘I want to shout my accusation.’ The film ends with Jue Hui’s principled decision to leave his family for an implied greater cause: ‘I must get out among the people and do something.’ These socialist film adaptations negotiated with May Fourth discourse and the Shanghai legacy of family melodrama by offering an alternative socialist imaginary of family.

Unlike classical Hollywood narration, which features a dual plot of heterosexual romance and work, the family melodramas discussed in this chapter featured a dual plot of family and work. The work ethic that propelled these narratives forward often led to frustration and exploitation: in Spring Silkworms, Old Tongbao’s rural superstition and work ethic are out of touch with the political and economic reality of China in the 1930s. The protagonists in This Life of Mine and The New Year’s Sacrifice finally find disappointment, not fulfilment, in their work. In The Lin Family Shop, the shop owner’s work ethic leads to a situation where ‘the big fish eats the small fish [and] the small fish eats the shrimps.’74 Unlike these, Revolutionary Family idealises a new socialist work ethic that is also a family ethic: the greatest fulfilment lies in work for the Party, with its vast support network serving as a family.

In line with Mao’s propagation of the ‘combination of revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism’ in 1958, Revolutionary Family created Zhou Lian as a socialist model citizen – in sharp contrast to Xianglin Sao’s portrayal as a literary and cinematic icon of the pre-revolutionary era.75 The fact that the screen image of Zhou Lian corresponded to real-life Party member and author Tao Cheng not only lent authenticity to the film, but also represented a temporal shift to contemporaneity in the genre of family melodrama. The revolutionary romanticism of Revolutionary Family lies in its idealisation of male martyrdom and focus on women as survivors, single mothers and potential revolutionaries – like teenage daughter Xiaolian. This moral and political investment in the maternal and nurturing roles of women went hand-in-hand with the representation of the Party and its vast network of support as male figures of authority, whose presence filled the void left by the death of father Jiang Meiqing.76

The shift in revolutionary temporality away from the past can also be seen in Li Shuangshuang, an adaptation of Li Zhun’s The Short Biography of Li Shuangshuang, published in series in People’s Literature in 1960. As part of the Great Leap Forward Campaign, Li Zhun, like many artists, experienced rural life, living in the home of a female team leader in a village in Henan. Li’s experience among the female peasantry allowed him to witness the so-called socialist transformation of rural life, which became the inspiration for his serial novella. The Short Biography of Li Shuangshuang became an instant success and caught the attention of director Lu Ren, who invited Li to serve as a screenwriter for the film.

In the early 1960s, revolutionary heroism was attributed to the quotidian and the everyday. Unlike earlier family melodramas that had incorporated melodramatic shocks and tragic climaxes, Li Shuangshuang focused on everyday marital conflict as a microcosm of underlying tensions and contradictions in the rural economy. Echoing the popular saying ‘women hold up half the sky’, Li Shuangshuang portrayed its outspoken eponymous protagonist as a good woman, good wife and good mother. The film depicts marital strife in the daily routine between Li Shuangshuang and her husband Sun Xiwang in order to reflect conflicting ideologies and work ethics among the peasantry. Employing chronological narration with a dual plot of family and work, the film presents day-to-day misconduct, mismanagement, tensions and arguments between the couple and among villagers, succeeded by the husband Sun Xiwang’s gradual self-correction of his behaviour and the resulting reconciliation between husband and wife. At one point in the film, Li Shuangshuang unassumingly says that ‘the Party is our family member’. The happy ending of the film presents Li Shuangshuang as a model that her husband, the village and the audience learn from.

The incorporation of classical Hollywood narrative technique – especially chronological narration and heterosexual romance – in Chinese literary and socialist terms had profound implications for the ideological, aesthetic and entertainment values of film adaptations of literature. Chronological narration with a high degree of positive narrative resolution replaced the ambivalence and negativity that had characterised May Fourth critical realism. Heterosexual romance became the foundation of the socialist goal and imaginary of marriage, procreation and family for which the Party served as a spiritual pillar. The genre of family melodrama was therefore suitable for propagating the socialist work ethic, morality and family values. Where May Fourth literature had often depicted family dissolution and the tragic prototypes of displaced widows, socialist film adaptations of that literature transformed the generic conventions of family melodrama to turn victimised women into revolutionary icons. The socialist investment in femininity and love of the Party were embodied in the maternal figures of revolutionary heroines, fulfilling Mao’s ideological and aesthetic principle of ‘a combination of revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism’.

After World War II, various realisms developed at a historical juncture: neorealism in postwar Italy, socialist realism as communist aesthetic, and classical Hollywood cinema. André Bazin pointed to the rise of neorealism as ‘a moment of particularly overt ideological conflict in cinema’, one in which, Italian neorealism and Hollywood cinema were opposites: ‘Italian neorealism embodies the idea of culture as critique’, whereas ‘Hollywood cinema presents itself as the epitome of entertainment, not necessarily mindless but not particularly political, compliant and not resistant, escapist and not engaged.’77 Socialist realism and ‘a combination of revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism’ in Chinese cinema sought to offer political and ideological education along with entertainment. The aesthetic experiment in screenwriting after 1949 created an alternative realism, in dialogue and competition with other realisms in different historical and ideological contexts.